Germany is a bankrupt concern, says The Daily Mail. A denial is expected every hour from Herr MICHAELIS, who is Germany's Official Deceiver.

Much sympathy is felt in Germany for Admiral VON TIRPITZ, whose proposed cure in Switzerland is off. His medical adviser has advised him to take a long sea voyage, but failed to couple with the advice a few particulars on how to carry it out.

Patrons of the royal theatres in Germany who pay in gold can now obtain two seats for the price of one. This is not the inducement it might seem to be. The German who used to buy one ticket and occupy two seats is almost extinct.

A chicken with four legs and four wings is reported from Soberton. Did it come from any other place we should receive the story with suspicion.

"New Labour troubles are brewing," declares The Evening News. The chief Labour trouble, however, seems to be not brewing.

One sportsman, says a news item, has landed seventy-seven pounds of bream at Wrexham. It may have been sport, but it has all the earmarks of honest toil.

A man charged with smoking in a munitions factory told the court he was trying to cure the toothache. A fine was imposed, the Bench pointing out that the man was lucky not to have lost the tooth altogether.

As a means of preserving the memory of hero M.P.s, Mr. WINSTON CHURCHILL suggests a name-plate on the back of the seats they had in the House. We understand that Mr. GINNELL resolutely refuses to have such a plate on the back of his old seat.

Honour where honour is due. A man named KITE told the Willesden magistrate that he had joined the Royal Flying Corps, and the magistrate refrained from being funny.

Light cars are now becoming very popular, says The Autocar. We understand that they have always been preferred by pedestrians, who realise that they make only a slight indentation in the person as compared with the really heavy car.

"Whatever else may happen," says a contemporary, "the final decision as to Stockholm rests with the Government." Our contemporary is far too modest. A few months ago the final decision would have rested with the stunt Press.

Portsmouth is to have three M.P.s, we read, under the Proportional Representation scheme, though it is not known what Portsmouth has done to deserve this.

Something like a panic was caused in the City the other day when news got round that no mention of Mr. WINSTON CHURCHILL appeared in a Morning Post leader.

A postwoman charged at Old Street Police Court admitted that she had swallowed a postal order and a pound Treasury note. Some women have a remarkable objection to using the ordinary purse.

A woodworm in the timbering of Westminster Hall has been attacked with a gas-spray by the Board of Works. The little fellow put up a gallant fight and died bravely defending his third line trenches against a vastly superior force.

The Vienna Neue Freie Presse says that so far £18,000,000,000 has been spent on the War. But even those who contend that it might have been more cheaply done admit that the notice was too short to enable the belligerents to call for tenders.

In a Brixton tramway car the other morning Mr. LLOYD GEORGE, it is announced, had to borrow coppers from a companion to pay his fare. The most popular explanation is that he had spent all his money in buying the latest editions of the evening papers.

According to the Acton magistrate, under new instructions boys over fourteen must pay their own fines or go to prison, parents paying the fines for those below that age. This class legislation is bitterly resented by some of our younger wage-earners, who intend to insist upon their right to pay for their own amusements.

People living next door to a post-office where burglars blew open the safe thought it was an air raid and went into the cellar. A suggestion that signals, clearly distinguishable from those used in air raids, should be used on these occasions, is under consideration in the right quarter.

The FOOD CONTROLLER has advised the Liverpool Corporation that vegetable marrows are not fruit. There is a growing belief among jam manufacturers that Lord RHONDDA'S business ability has been overrated.

["But how to get a cab without whistling—that is the problem."—Evening News.]

A very good plan is to purchase a camp-stool and sit down in the Strand until a taxicab breaks down. When you are sure that the driver is not looking step inside.

Taxi-drivers are human, and if caught young can be made so tame that they will take fares by the hand.

An excellent plan is to make a noise like a road under repair. But be careful that the driver does not make a noise like a cab going over a human body.

The essential thing is to interest the driver in your personal affairs. If you see a car rushing along stand in the road. When the cab pulls up, ask the driver if he would like to see your cigarette pictures.

We were discussing that much discussed question, whether it is better to be wounded in the leg or in the arm, when young Spilbury butted in.

"I don't know about legs and arms," he said, "but I know there are certain advantages in having your head bound up." Spilbury's own head was bound up, and we all said at once that of course the head was much the worst place in which to be wounded.

"It may be," said Spilbury. "But what I said was that there are certain advantages in having your head bound up. That's not quite the same thing as being wounded in the head. For instance, I wasn't wounded in the head. I was wounded in the jaw. But they can't bandage the jaw without bandaging the head, which I have found has certain advantages."

"I can't see where they come in," said Cotterell, "except so far as personal appearance goes, of course. I won't say that that nun-like head-dress doesn't become you. You look almost handsome in it."

"It is extremely polite of you to say so," said Spilbury, "but I was not thinking of that. I was thinking of Dulcie."

There was silence for a space, and then Cotterell said, "If you do not mention her other name, you may tell us about Dulcie."

"I became acquainted with Dulcie" Spilbury began, "or the lady I will call Dulcie—for that is not actually her name—while we were quartered at a camp somewhere in England. Friendships ripen quickly in war-time. I was signalling officer, and perhaps I signalled to Dulcie rather more than I meant. I won't say I was wholly blameless in the matter."

"I shouldn't," said I.

"I won't," said Spilbury. "After I went out we corresponded. But after a little I began to see I had perhaps over-estimated my affection for Dulcie. At the time I was wounded I had owed her a letter for some time, I remember. When I got back to England I did not let Dulcie know at once, but after a while she heard where I was in hospital and came to see me. In the meantime I had met Daphne."

"This is a highly discreditable story," said Cotterell. "I am sorry I allowed you to tell it."

"I won't finish it, then," said Spilbury complacently.

"Yes, you must finish it now."

"Well, I didn't quite know what to do about it. I had felt when we were somewhere in England that Dulcie brought out all that was best in me. I found now that Daphne brought out still more."

"She must have been a clever girl," I said.

"She was," said Spilbury, "but I saw that if they both tried at once they might bring out almost too much. I had to act quickly, for Dulcie was already by my bedside."

"'Well, Reggie,'" she said.

"I looked at her kindly but firmly.

"'I think there is some mistake,' I said. 'I don't remember having met you.' Then I pointed to my bandaged head, and added, 'I may have forgotten. My memory isn't very good.'

"Well, she chatted a bit about general subjects, and then departed. I don't mind saying I felt rather a worm. Also I wasn't quite sure that Dulcie couldn't bring out more that was good in me than Daphne, after all. So I thought about it a bit, and then wrote and said I'd remembered her now, and would she come again to see me? She wrote back and said she would, and I must congratulate her as she was just engaged to be married. That was a rotten day, I remember, because in the afternoon Daphne came and said that she was engaged to be married too. A perfect epidemic. But that's beside the point."

"The point was, if I remember rightly," said Cotterell, "that it's a great advantage to have your head bandaged. Have you quite proved it?"

"No," said Spilbury thoughtfully. "Now you mention it, I hardly think I have. But if my story acts as an example and a warning I shall be satisfied."

So as an example and a warning (though of what or to whom is not too clear) I have recorded it.

The full programme for the season of Promenade Concerts which opened last Saturday is, as usual, a most interesting document, and we are of course glad to see that our gallant Allies are so well represented. But it is the function of the critic to criticise, and we may be permitted to express a mild regret that our native school, though by no means excluded, does not make so good a show as its energy and talents would seem to warrant. Our native composers are especially noticeable for their wide range of themes, for the Celtic and Gaelic glamour which they infuse into their treatment of them, and for their realistic titles. We have drawn up a list of instrumental works which illustrate these characteristics, but which are unfortunately conspicuous by their absence from Sir HENRY WOOD'S scheme. As, however, it is subject to alteration we are not without the hope that some of them may yet be included in the list of works to be heard at the Queen's Hall in the next six weeks.

SYMPHONIC VARIATIONS. "Father's lost his collar-stud." Hans Halfburn.

KELTIC KORONACH. "Wirrasthrue." Seumas Macdthoirbwlch.

FUNERAL MARCH OF A CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTOR. Nelson Wellington.

SIAMESE LULLABY for Sixteen Trombones. Quantock de Banville.

FANTASIA. "Wardour Street." Yokeling Ffoulkes.

MANX MEDITATION for Revolving Orchestra. "Laxey Wheel." Bradda Quellyn.

OVERTURE. "Glasgow Fair." Talisker McUsquebaugh.

CAMBRIAN "SNEEZE" for Full Orchestra. Taliesin Jones.

ORCHESTRA MUSINGS ON IRISH RAILWAY STATIONS. Dermod MacCathmhaoil. (a) Stillorgan. (b) Dundrum. (c) Bray.

BUBBLINGS FROM BUTE. Diarmid Dinwiddie.

DITHYRAMBIC ODE. "The Belles of Barmouth." Ivor Jenkins.

VALSE FANTASTIQUE. "Synthetic Rubber." Marcellus Thom.

In silks and satins the ladies went

Where the breezes sighed and the poplars bent,

Taking the air of a Sunday morn

Midst the red of poppies and gold of corn—

Flowery ladies in gold brocades,

With negro pages and serving-maids,

In scarlet coach or in gilt sedan,

With brooch and buckle and flounce and fan,

Patch and powder and trailing scent,

Under the trees the ladies went—

Lovely ladies that gleamed and glowed,

As they took the air on the Ladies' Road.

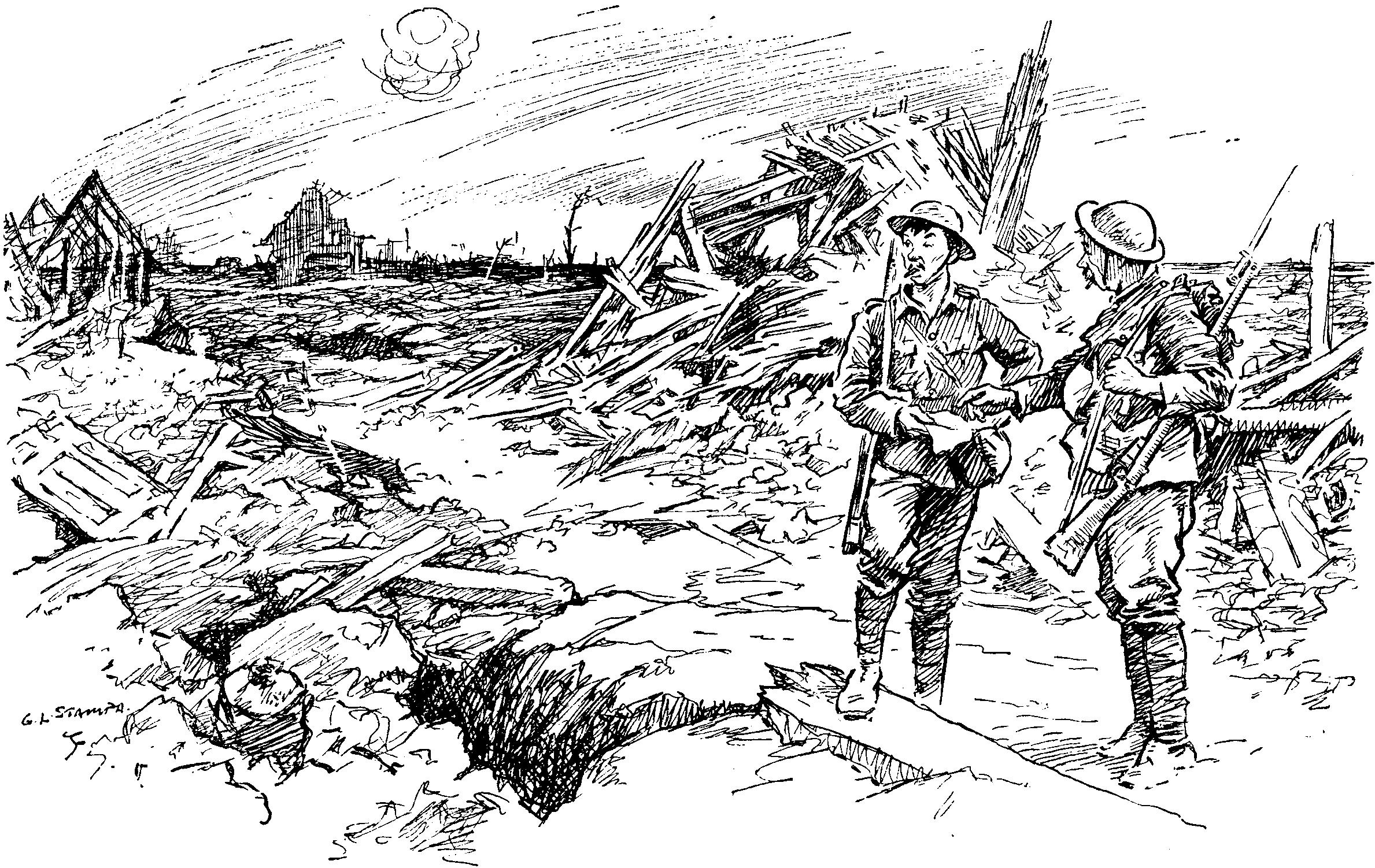

Boom of thunder and lightning flash—

The torn earth rocks to the barrage crash;

The bullets whine and the bullets sing

From the mad machine-guns chattering;

Black smoke rolling across the mud,

Trenches plastered with flesh and blood—

The blue ranks lock with the ranks of gray,

Stab and stagger and sob and sway;

The living cringe from the shrapnel bursts,

The dying moan of their burning thirsts,

Moan and die in the gulping slough—

Where are the butterfly ladies now?

PATLANDER.

"No persons were injured and no houses were bit by the bombs."—Sunday Pictorial.

But they barked horrid.

"Brain-fag! That's wot we 'orses are suffering from. Ah! there's bin a deal o' queer things 'appen since they women started on the farm! I shan't never forget the first time one of them females come into my stall. The roan pony, wot's got sentimental thro' being everlasting driven in the governess-cart, sez she was a pretty young woman. I never noticed nothing 'bout 'er 'cept the pink rose in 'er button-'ole. I never 'eard tell of a farm 'and with a pink rose in 'is shirt before. Maybe such carryings on is all right for they grooms an' kerridge-'orses, but it ain't 'ardly decent for a respectable farm 'orse. So when this 'ere woman come along I up and 'as a grab at it. D'ye think she'd 'it me? I never 'ad such a shock in me life, not since I went backwards when the coal-cart tipped! Lor, lumme! if she didn't catch 'old of me round the neck an' kiss me! 'Oh, you darlin'!' she said, 'did you want me rose then, ducky?' I'm a brown 'orse, but I tell you I blushed chestnut that morning. 'Course the roan pony next door started giggling, and then she 'ad to go and kiss 'im, and that settled 'is little game.

"Well, then she come along with the collar. I need 'ardly tell you 'ow often she tried to fix it on the wrong way round. There I 'ad to stand with 'er shoving the blooming thing till I thought my 'ead would 'ave dropped orf. Being a female, it took 'er some time before she thought of putting the big end of the collar up first, but when she did I just took and put me 'ead thro' and nipped orf 'er rose. 'If that don't fetch you,' I sez, 'nothink will.' If that woman 'ad clouted me on the 'ead then, I'd 'ave loved 'er; 'stead o' which she calls out to 'er pal 'oo was mucking round cleaning out the stalls with a broom-'andle, 'May!' she sez. 'Oh, do look!' she sez, 'this 'ere dear 'orse,' she sez, ''as bin and ate my rose!'

"Well, when we done all the kissing and that, she led me out of the stall, and I promise you I was a sight! My bridle was over one eye and my girths 'anging loose. Maybe that was my own fault; when she started to pull in the straps 'course I blew meself out, same as any 'orse would, just to give 'er something to pull on. 'Oh dear!' says the female. 'Poor 'orse, this 'ere girth's too tight!' Any'ow, when we did get to the 'ayfield she 'ad to fetch a man to put me into the rake. Well, 'e told her 'ow to go on, and we moves orf. That wasn't 'arf a journey! Wot with 'er pulling one way an' pulling another, I got fair mazed. Arter a bit I stopped. ''Ave it your own way then,' I sez. Next minute I 'eard 'er calling out like a train whistle to the bailiff, 'oo was passing. 'Smith!' she sez, 'this pore 'orse is tired!' And Smith sez, 'Tired!' 'e sez; ''e's lazy!' And with that 'e fetched me one. 'All right, my girl,' I thinks; 'you wait a bit.'

"This 'ere field run past a railway, and when Smith 'ad gone I seen one of the signals on the line go down. 'That's the ticket!' I sez, and when the train come by I up and shook me 'ead. The woman didn't say nothing, so I gives a 'op with all me feet at once. Still she don't say nothing, and I couldn't feel 'er on the reins, so I done a few side steps. And then she spoke, and this is wot she sez: 'Oh!' she sez, 'please don't!' and started crying.

"There's no vice about me, and when she begun 'er game I stopped mine. You'd 'ardly believe it, but that 'ere woman got down orf that 'ere rake and she come round to my 'ead and, 'Pore darling,' she sez, 'was you frightened of the train then?' Me! wot's 'ad me life in the London docks till I come 'aying 'long of the War.

"Ah! I reckon the roan pony's right: You can't 'ave the larst word with females!"

"For sale—A large stone gentleman's diamond ring, set in a solid gold band."—Cork Examiner.

The National Museum should not fail to secure this remarkable relic of the Palæolithic Age.

From a report of Mr. HENDERSON'S speech on Stockholm:—

"The Prime Minister has been in favour again. What was a virtue in May ought of this conference once, and he may be so not to be a crime for us in August."—Daily Dispatch.

The Stockholm atmosphere appears to be fatal to clearness of statement.

Profound stillness reigned in the wardroom of H.M.S. Sinister, broken only by the low tones of the Paymaster and the First Lieutenant disputing over the question of proportional representation and by the snores of the Junior Watchkeeper, stretched inelegantly on the sofa. The rest of the occupants were in the coma induced by all-night coaling. Into this haven of quiet burst the ship's Doctor in a state of exaggerated despair. He groaned and, sinking into a chair, mopped his forehead ostentatiously. The disputants ceased their discussion and watched him intently as though he were some performing animal.

"Gentlemen," said the Paymaster presently in tones of sepulchral gloom, "the neophyte of ÆSCULAPIUS, to whose care the inscrutable wisdom of Providence has entrusted our lives, is being excruciatingly funny. Number One says it is belated remorse for the gallant servants of His Majesty whom he has consigned to an untimely grave."

"Poor jesting fool," said his victim, "little he knows that even now Heaven has prepared a punishment fitted even to his crimes. I have seen it—nay, I have spoken with it."

"Suppose," intervened the Commander, "that you postpone this contest of wits and let us have your news."

"Certainly, Sir," acquiesced the Doctor. "It's Pay's new assistant. He's ..." the Doctor paused in search of adequate expression, "he's here. He is, I fancy, at this moment slapping the skipper on the back and asking him to have a drink. He called me 'old socks.'" The doctor shuddered. "Then he said he expected this was some mess; Naval messes were always hot stuff. He wanted to spin me yarns of his infant excesses, but I choked him off by telling him he ought to report to the skipper. You'll have to look after him, Pay. That will give you some honest work for a change."

It must be confessed that at lunch the newcomer justified the Doctor's worst forebodings. Afterwards the First Lieutenant and the Paymaster had an earnest colloquy. Then the latter sought his new assistant; he found him gloomily turning over the pages of a six-months-old illustrated paper.

"What do you think of the ship?" he asked cheerfully.

"Rotten slow lot," replied the A.P.; "I tried to make things hum a bit at lunch and they all sat looking like stuffed owls."

"Ah, you'll find it different this evening after the Commander has gone. Bad form to tell smoking-room yarns while he's here."

Meanwhile the First Lieutenant visited the Commander in his cabin.

"Very well," said the latter on parting; "only mind, no unnecessary violence."

"I understand, Sir. I hope it won't be necessary."

The Assistant Paymaster had no cause to complain of lack of hilarity at dinner. The most trivial remark was greeted with roars of merriment. When the KING'S health had been drunk the Commander pleaded letters and left the ward-room. Instantly a perfect babel arose. Everyone seemed to be asking everyone else to have a drink. The newcomer selected a large whisky.

"Wilkes," said the First Lieutenant, "one large whisky, one dozen soda, one dozen ginger-beer and two large bottles of lime-juice."

"Large bottles, you blighter!" he yelled after the back of the astonished marine who went out to fulfil this remarkable order.

"Now," said the Junior Watchkeeper, when all the glasses had been filled, "I call on Number One for a song." Amid vociferous applause the First Lieutenant, clasping a huge tumbler of ginger-beer, rose unsteadily. Without the semblance of a note anywhere he proceeded to bawl "A frog he would a-wooing go." A prima donna at the zenith of her fame might have envied his reception. The Junior Watchkeeper broke half the glasses in the transports of his enthusiasm. "Come along, Doc," said the singer as soon as he could make himself heard; "give us a yarn." With the assistance of his neighbours the Doctor placed one foot on his chair and the other on the table. "Say, you fellows," he said thickly, "jolly litl' yarn—Goblylocks an' Three Bears."

Overcome, apparently, by tender recollections he was silent, and fixed the walnuts with a dreamy stare.

"Go on, Doc!" "Goldilocks, Goldilocks." "The Doc," said the Paymaster, "was always a devil for the girls."

"Pay," remonstrated the First Lieutenant sorrowfully, "that's the third half-penny for swearing this year. You mean that the Doctor has always evinced a marked partiality for the society of the gentler sex."

Punctuated at the more exciting points with breathless exclamations of horror and amazement from his audience, the Doctor's rendering of the story proved an overwhelming success. As he painted in vivid periods the scene where Goldilocks was discovered by all three bears asleep in the little bear's bed, the First Lieutenant broke down completely and had to be patted and soothed into a more tranquil frame of mind before the story could proceed. Then there was a spell of musical chairs, the First Engineer obliging at the piano, and afterwards giving a tuneful West-Country folk-song at the Doctor's request. The Junior Watchkeeper, declaring his inability to remember anything, read half a column from the "Situations Vacant" portion of The Times, and amid the ensuing applause slipped quietly from the room in obedience to an unspoken signal from the First Lieutenant. After the Second Engineer had given an exhibition of what he asserted to be an Eskimo tribal dance, the First Lieutenant addressed the Assistant Paymaster.

[pg 153]"Now then, young fellow, it is your turn. D'you want to give us a yarn?"

But the boy had learned his lesson. "I'm afraid I don't know any yarns that would interest you, Sir," he said. "If you don't mind I think I'll turn in."

The First Lieutenant smiled on him with the mature wisdom of twenty-seven summers. "Quite right, my lad. By the way, you might look in at the bath-room on the way to your cabin and tell the Junior Watchkeeper that we shan't want the bath that he is filling from the cold tap. I'm very glad we shan't."

"Now is the opportunity for carrying out the recommendation of a Select Committee in 1908 that there should be a common gallery for men and women."—The Vote.

A sort of Mixed Grille, in fact.

"Wanted, Upper Housemaid of two; wages £30; 5 maids; two ladies in family; quiet country place."—Daily Paper.

Who said our upper classes are not feeling the War?

"Required, very small nicely Furnished House or Cottage. Bathroom and good private girls' school within easy walk essential."—Daily Paper.

There is nothing so invigorating as a little walk before one's bath.

A prisoner, Gunner Grogan, E.,

To-day will be brought up to me

For impudence and sloth;

Reveillé only made him sneer;

Aroused, he lipped a Bombardier

(And very natural—both).

And I shall counter, with disdain,

His feeble efforts to explain

Or justify such deeds.

It will be funny if I fail

To twist young Gunner Grogan's tail,

That being what he needs.

I know he isn't really bad;

Myself, I rather like the lad.

(And loathe that Bombardier!)

Beneath his buttons—none too bright—

May lurk the spirit of a knight—

A thwarted cavalier.

For some who fought at Creçy, too,

Snored on or scoffed when trumpets blew,

And presently were caught;

And when the clanking N.C.O.'s

Came round to prod them, I suppose

They up and spoke their thought.

Then they were for it; up they went

Paraded by the Prince's tent,

While he, to meet the crime,

Recalled the nastiest words he knew,

And learned the worst that he could do

From "K.R." of the time.

And yet such criminals as those

Did England proud with English bows

As schoolboys have to read;

And Gunner Grogan would to-day

Prove every bit as stout as they

Should there arise the need.

But just as heroes of Romance,

Who dodged parades with half a chance,

Were strafed—and mighty hard—

So likewise Gunner Grogan, E.,

Employed in making history,

Will do an extra guard.

"We are informed by the Right Hon. the Lord Mayor of Bristol that his Lordship still has a supply of famous men connected with the great war, and will be pleased to supply them to applicants."—Evening Times and Echo (Bristol).

Will the PRIME MINISTER please note?

"A conference of the Ministers of departments concerned will take place in London to arrange measures for their execution."—Daily Chronicle.

Anticipated comment from The Mourning Toast: "And quite time, too."

"Lord Lawrence, once Viceroy of India, said, 'Notwithstanding all that English people have done to benefit India, the missionaries have done more than all other agonies combined.'"—Malay Tribune.

Missionaries in the East have a lot to put up with.

MY DEAR WIFE,—Yours to hand of the 10th inst., and contents, re son, noted. I observe that you are for the moment satisfied with his progress, and that you feel yourself in a position to be able to see your way to inform me that he is beginning to have and express ideas of his own on all subjects. He shows himself a fine fellow, and you have every reason to be as happy as it is possible to be in wartime.

By the same post arrived the new uniform from Dover Street, London, W. You will be glad to hear that Messrs. Blenkinson have done us proud, managing to carry out your many suggestions without departing from regulation. They make a fine fellow of me, neat but not gaudy, striking in appearance without being offensive to the eye. Once more they too have shown themselves fine fellows. We are all fine fellows; my dear, you are positively surrounded on all sides by fine fellows, and it would look as if, given peace, we are all together going to be as happy as the day is long.

So I thought at first blush; but are we so sure? The separate ingredients are excellent; there couldn't be a better son than Robert or better tailors than Messrs. Blenkinson. But how will they blend? Mind you, I'm not daring to doubt the courtesy and tact of a single Blenkinson; but these views which son Robert is beginning to form, where will they lead him ... and us ... and the Blenkinsons? Again, I'm not suggesting that Robert will ever go to such lengths in view-forming as to dare to attack such an anciently and honourably established firm as Messrs. Blenkinson; indeed, I could almost wish it might fall out that way, and that they and I might continue, without intervention, upon our present terms of mutual esteem and entire satisfaction. If things stand so well between us, while I am but young, claiming no higher rank or standing than that of Captain (Temp.), how much more must we flourish when I have risen to those heights to which we know I am bound to reach in my full maturity? Against such an alliance even the youthful and vigorous Robert would hurl himself and his criticisms in vain. No, I foresee a danger more subtle and formidable than that.

Some of the very first views that Robert forms will be on the subject of clothes. His very desire to be perfectly dressed will take him to Blenkinsons', and, when he has spent two hours trying on the very latest, his desire to get me, at any rate, passably dressed will induce him to say to Mr. Blenkinson, senior: "I say, can't you do something to stop the governor wearing clothes like that?"

Blenkinson, having long anticipated and dreaded this, will at once hasten round to the back with the tape-measure; but Robert will catch him when he comes round again and say, "I shouldn't have believed that you would ever consent to make such clothes as he insists on wearing."

Blenkinson perforce will smile that deferential and conciliatory smile of his, which seems to say: "We entirely agree with you, Sir, but it isn't for us to say so."

Robert, blown out with conceit, upon being tacitly corroborated by Blenkinsons in a matter of taste, will pursue the subject mercilessly, until his victim is forced into some definite statement. Looking round to see that he cannot possibly be overheard, Blenkinson, senior, will be led by his too perfect courtesy to commit himself. "Well, Sir," he will murmur, "we have on one or two occasions dared to hint that his cut was rather out of date, and would he permit us to alter it in some small particulars? But Sir Reginald" (or shall we make it "the General"?) "prefers, quite rightly, of course, to decide these things for himself."

"'Quite rightly' be blowed," Robert will retort. "We know and he doesn't. Can't you make him understand? You can sometimes get him to be reasonable, if you stick to him long enough."

Blenkinson will be quite unable to let his old and honoured customer go entirely undefended or unexcused on so grave an issue. "We fancy, Sir, that the General" (or shall we say "His Lordship"?) "understands just as well as we do, Sir, but...."

"But what?" Robert would exclaim, a little exasperated to hear it suggested in his presence that I understand anything.

Mr. Blenkinson, senior, will rub his chin, wondering very much whether he is justified in allowing himself to go so far as to hint at the truth in this instance. "But—er—well, Sir," will be extracted from him at last, "we gather—er—we gather, Sir—er'm—her Ladyship insists."

I see Robert's face clear and I hear him say in quite a different tone, "Oh, I'll soon manage mother for you." And off he trots home, and in a week or less I have to adopt his ridiculously ugly, obviously impracticable and damnably uncomfortable fashions—tight trousers and high collars, no doubt.

Yes, that's where Robert, and you, with your Robert, are leading me, confound you both. It will be as bad as that; confound you both.

"Don't speak like that, even in jest," you'll say brazenly.

"But damme, Mary—"

"And I certainly will not have my name coupled with that sort of language, please."

I shall appeal to Robert to bear evidence that I am the injured party, and not you. Robert of course will stand by you, and you, worthless woman that you are, will sink your identity and sacrifice your soul and stand by TIGHT TROUSERS AND HIGH COLLARS.

And I shall get red in the face (and at the back of the neck).

And in the end I shall have to make good by taking you all out to the most expensive dinner, theatre and supper possible—very nice for you two, no doubt, but what about me in those infernal trousers and collars?

It will right itself in the end, for I cannot believe your reason will permanently forsake you, even for that precious nut of a Robert. Eventually we shall prefer, unanimously you and I, to slink about the back streets, clothed in our own ideas, rather than promenade the fashionable parts clothed in Robert's.

Do you say to yourself that that supreme test, the sacrifice of Piccadilly, Bond Street and the Park, is too much? Don't cry, darling; it will never be as bad as that. And why? Because, according to that incredibly stupid young man, Robert, Piccadilly, Bond Street and the Park will then be the back streets, in which no decent people, except out-of-date, old-fashioned fogeys like ourselves, would ever consent to be seen. So it is really myself who is still alone. Yours, R.

If the casual gods send inquiring strangers into my camp, let them (the intruders) be civil, please, or at least be male. Citizens I can at once wave away with a regretful nescio vos; foot-officers are decently reserved in their thirst for knowledge of an essentially Secret Service; but officers' wives—

I was growing to like the Royal Gapshire Cyclists (H.D.), my neighbours in the next field, until last Friday, when they perpetrated their Grand Athletic Tournament. Quite early in the day twos and threes of subalterns, with here and there a company commander, dribbled across with a diffident wish to be shown round the guns, and round we went. By the ninth tour I was wearying fast of the cicerone act, and hoping they would not mistake my dutiful reticence for stuffiness. They [pg 155] had made me free of a mess that has its points. Then, towards tea-time, She came. The Major, who brought, introduced Her, apologised (not for bringing Her) and withdrew. He was due to start the Three-Legged Obstacle Relay. She, on the other hand, was so interested, and would I, etc.? Would I not!

"Lovely woman!" thought I. "Fit soil for a romantic seed! Farewell reserve and half-told truth!" I then proceeded to describe unto her things unattempted yet in Field, Garrison, or High Angle Ballistics. Her first question (pointing to the recoil-controlling gear of No. 2 gun), whether both barrels were fired at once, gave me a cue priceless and not to be missed. My imagination held good for full fifteen minutes, and by the time we were ambling back to the fence I had got on to our new sensitive electrical plant for registering the sound, height, range, speed and direction of hostile aircraft. The fluent ease of it intoxicated, and I was lucky not to mar the whole by working in something crude and trite about the pilot's name.

She departed, smiling radiant thanks, and I thought no more of it until this morning, when Post Orderly handed me the following note:—

"DEAR SIR,—It was too kind of you to tell me all about your guns the other day, and it was too bad of me to let you. I ought to have mentioned that my husband is the Colonel Strokes, of the High Angle Ordnance Council. One of his favourite remarks is that the one woman of his acquaintance who knows more about artillery than a cow does of mathematics is

"Very sincerely yours,

"EVELYN STROKES.

"P.S.—Do you by any chance write?"

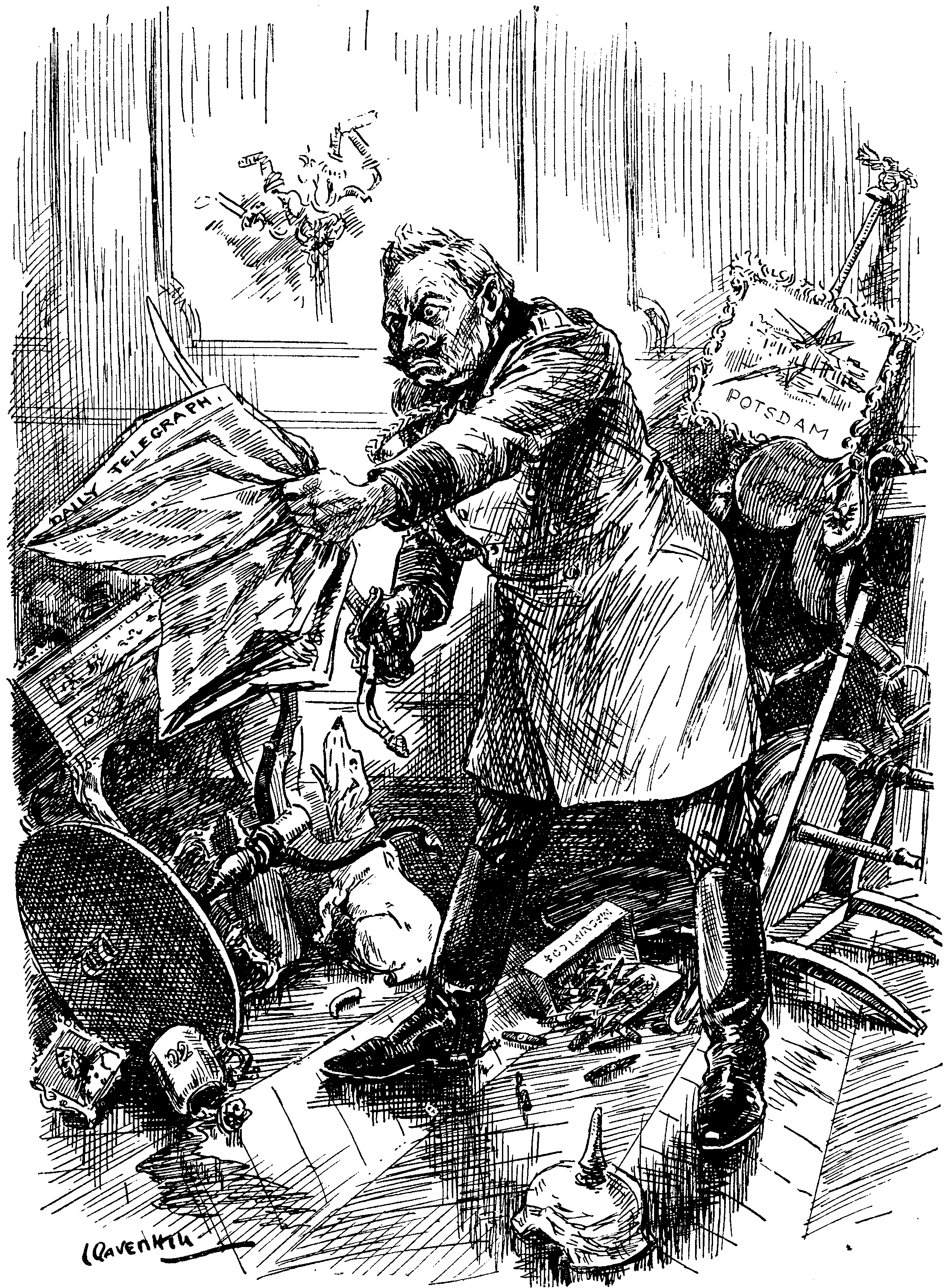

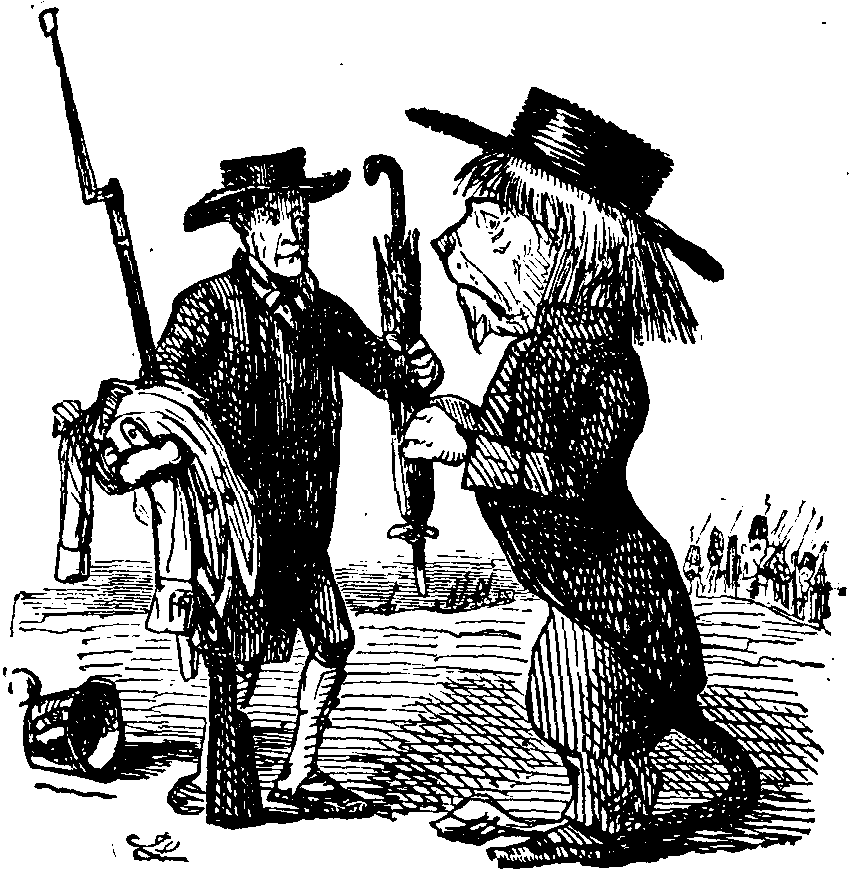

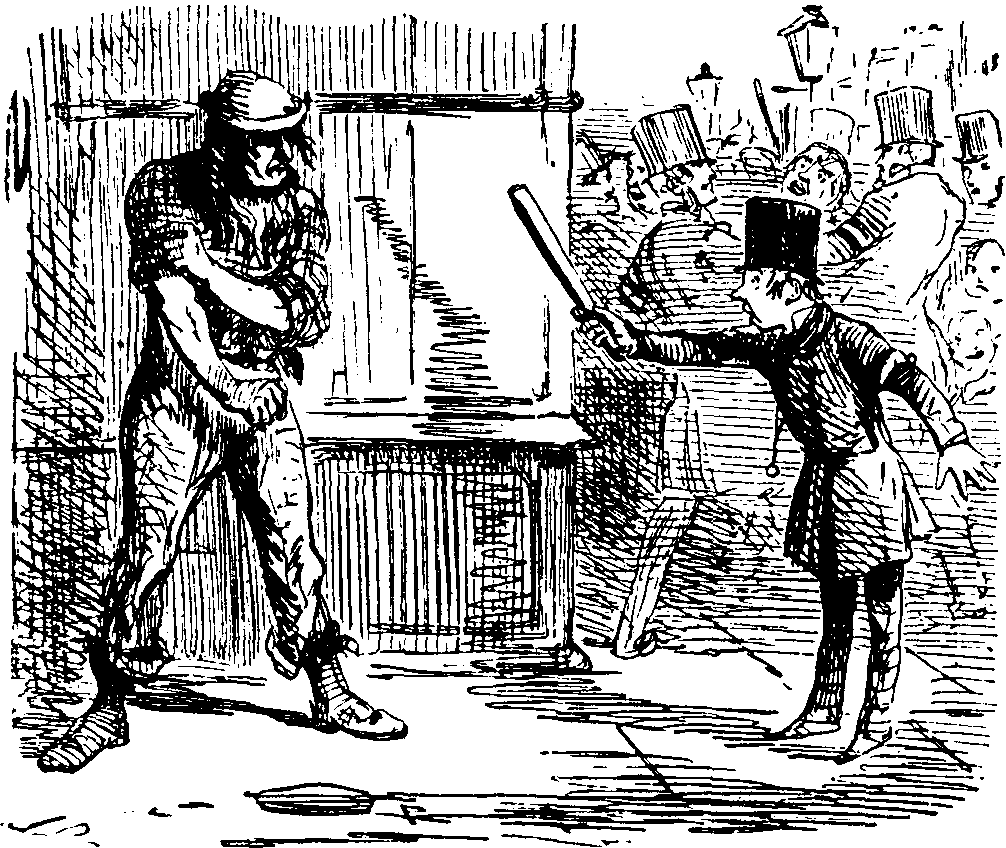

Recruit. "EXCUSE ME, SIR, BUT HAVE THE GERMANS THE SAME METHODS IN BAYONET-FIGHTING AS WE HAVE?"

Instructor. "LET'S HOPE SO. IT'S YOUR ONLY CHANCE."

From a company's report:—

"Interim dividend on the Ordinary snares for half-year ended July 31, 1917, at the rate of 10 per cent. per annum, less income tax."—Evening Paper.

"A twelve-year-old boy was at Aberavon on Thursday sent to a reformatory school for five years. He was charged with stealing 5-1/2 6-5/8 Nbegetable marrows from an allotment."—Western Mail.

It is supposed that he intended to reduce them to decimals.

There is no truth in the rumour that spectacular cricket is to be resumed. It is perfectly true that a section of the public who are devoted to watching the game and cannot understand why, because the nations happen to be at war, this favourite summer recreation should be denied them, have been agitating for the Government to arrange with the War Office to release all first-class cricketers now in the Forces, so that they may be free to play matches at home. It is also true that the Government, having refused to do this, subsequently, in view of the arguments urged by a deputation of cricket enthusiasts, agreed to do so, since it has always set its face against any pedantic rigidity of purpose. But none the less no such matches will be played, for the simple reason that the cricketers themselves refuse to come back until their job is finished.

"Boots.—Save nearly 50% buying Factory direct."—News of the World.

On second thoughts we think we shall continue buying one pair at a time.

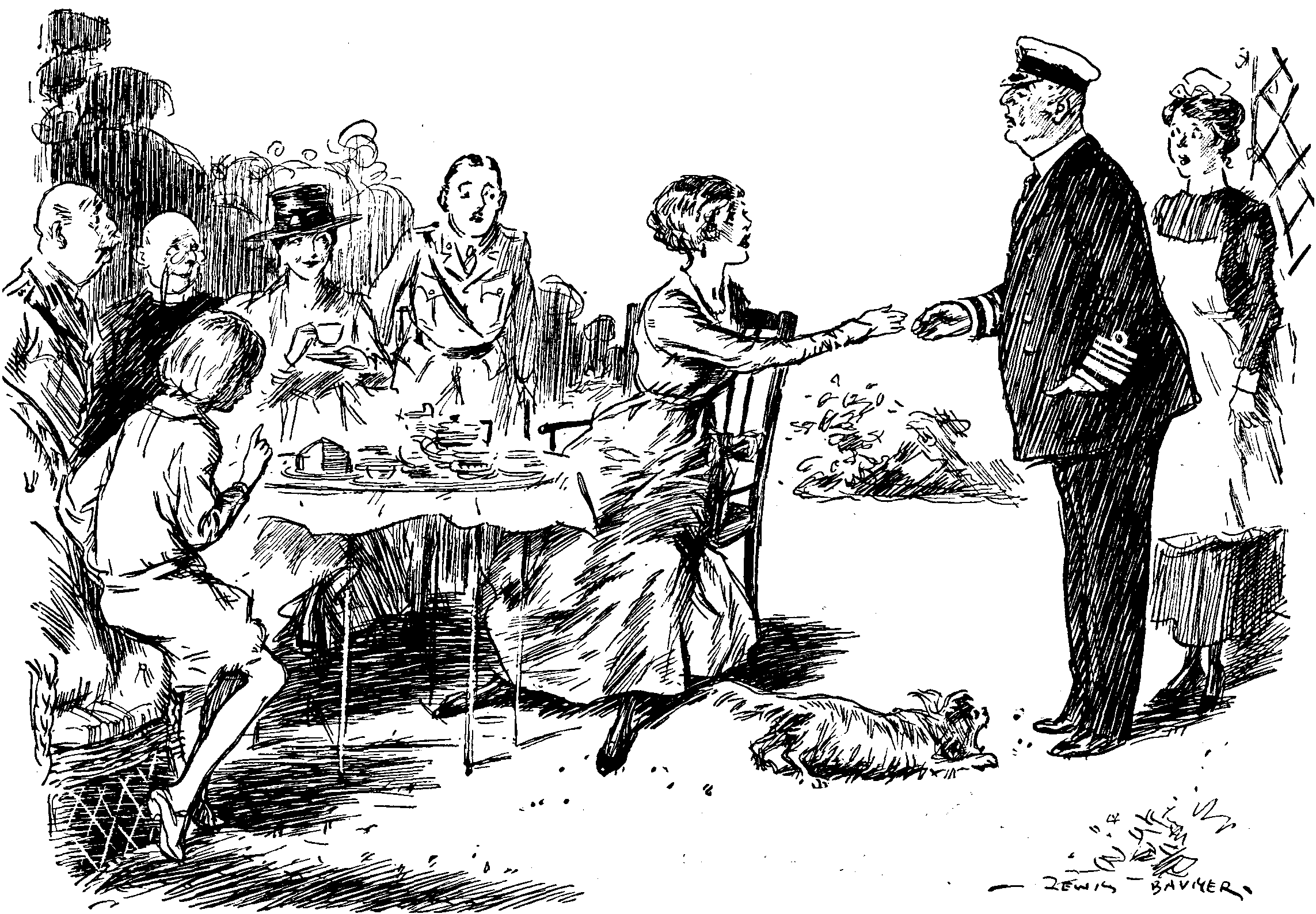

Little Girl (as distinguished admiral enters). "BE

QUIET, FIDO, YOU SILLY DOG—THAT'S NOT THE

POSTMAN."

Little Girl (as distinguished admiral enters). "BE

QUIET, FIDO, YOU SILLY DOG—THAT'S NOT THE

POSTMAN."There are some men who dwell for years

Within the battle's hem,

Almost impervious, it appears,

To shot or stratagem;

Some well-intentioned sprite contrives

By hook or crook to save their lives

(It also keeps them from their wives),

And Jones was one of them.

The hugest bolts of Messrs. KRUPP

Hissed harmless through his hair;

The Bosch might blow his billet up,

But he would be elsewhere;

And if with soul-destroying thud

A monstrous Minnie hit the mud,

The thing was sure to be a dud

If only Jones was there.

Men envied him his scatheless skin,

But he deplored the fact,

And day by day, from sheer chagrin,

He did some dangerous act;

He slew innumerable Huns,

He captured towns, he captured guns;

His friends went home with Blighty ones,

But he remained intact.

We had a horse of antique shape,

Mild and of mellowed age,

And, after some unique escape,

Which made him mad with rage,

On this grave steed Jones rode away...

They bore him back at break of day,

And Jones is now with Mrs. J.—

The convalescent stage.

The world observed the chance was droll

That sent so mild a hack

To smite the invulnerable soul

Whom WILLIAM could not whack;

But spiteful folk remarked, of course,

He must have used terrific force

Before he got that wretched horse

To throw him off its back.

A.P.H.

"Many coolies of the savage tribes from the hilly places, who have been enlisted for the labour corps, were seen passing this town by train lately. Some had too few clothes. Our late Chief Secretary, the Hon'ble Mr. ——, was seen among them."—Times of Assam.

"All can sympathise with Mr. —— and his teetotal party in deploring the excesses of 'liquor' of any description, and the vice, want and misery it brings in its course. But we cannot for a single moment listen to their selfish and pitiful beatings, when we know that if their methods were carried out through the land it would people our beloved country with a virile race of effete degenerates."—Provincial Paper.

"Virile" is good, and should encourage the teetotalers to proceed with their "beatings."

"'Polybe,' writing in the Figaro, estimates the German losses at 20,000 horse de combat on the first day of the battle."—Local Paper.

"Following the Franco-German war an epidemic of smallpox raged throughout Europe, which was not checked until Jenner's famous vaccination discovery."—Liverpool Echo.

It is sad to think that JENNER's discovery, made in 1796, should have remained dormant till after 1870.

"Mr. Gerard's reminiscences have caused much perturbation in German Court circles."—Daily Paper.

Little scraps of paper,

Little drops of ink

Make the KAISER caper

And the Nations think.

"A money prize offered to boys at Barcombe, Suxxes, for killing cabbage butterflies resulted in over 4,000 insects being destroyed. The winner, Victor King, accounted for 1,395."—Liverpool Echo.

We congratulate him on his Suxxes.

"One new thing he [Mr. HENDERSON] disclosed was that in his pervious statement that carried the Conference to the Stockholm vote, &c."—Daily Mail.

As "pervious," according to WEBSTER, means "capable of being seen through," we think the printer is to be congratulated.

Member of Committee (interviewing candidate for training for farm work). "AND ARE YOU FOND OF ANIMALS—HORSES AND COWS?"

Candidate. "WELL, NO—NOT VERY."

Member of Committee. "BUT I'M AFRAID THAT'S RATHER NECESSARY."

Candidate (brightly resolute). "OH, BUT I SHOULD TRY NOT TO THINK ABOUT THEM."

I was due to go in front of the local Medical Board next morning, and I was seeking distraction in the evening paper. Suddenly my eye was caught by the headlines announcing the transfer of recruiting arrangements from the Military to the Civil authorities. This promised to be interesting.

All at once the room grew misty, and when the atmosphere cleared again I found myself in the open street. Before me was a palatial building with the words "Medical Board" carved on a marble slab over the main entrance.

I entered, and was immediately confronted by a liveried janitor who bowed obsequiously.

"I have come to be medically examined," I explained.

"Yes, Sir," he replied. "Will you be good enough to wait one moment, Sir, while I settle with your taxi-driver, and then I will take you to the waiting-room, Sir."

"I have no taxi," I said. "I just walked."

An expression of concern passed across his face.

"Oh, you shouldn't have done that, Sir. The Authorities don't like it. There is a special fund for such expenses, you know, Sir. Will you please come this way, Sir?"

I followed him along the corridor, and was shown into a luxurious apartment overlooking a pleasant garden. The janitor placed an easy chair in position for me, handed me a copy of Punch, and brought me a glass of wine and some biscuits.

"Now, Sir, if you will give me your papers I will send them up to the Board."

I handed the packet to him, and he left the room.

A few minutes later a message-girl entered.

"Are you Mr. Smith?" she inquired.

I confessed that I was, upon which she handed me a sealed envelope. I opened it, and found a letter and a cheque for five pounds. The letter ran as follows:—

"SIR,—The above-named Medical Board regrets its inability to examine you to-day. As you are no doubt aware, it is contrary to its rule to examine more than three persons in one day, and an unusually difficult case, held over from yesterday, has upset all its arrangements.

"The Board would consider it a favour if you could make it convenient to call again to-morrow morning at the same time.

"The enclosed cheque is intended to compensate you for the unnecessary trouble to which you have been put.

"Your obedient Servants ——"

Punctually at the time appointed I again entered the building, and was met by the same janitor.

"The Board is quite ready for you, Sir," he said. "Will you please ascend to the dressing-room, Sir?"

He committed me to the care of a lift-girl, who conveyed me to the second storey. Here I was handed over to a smart valet, who assisted me to undress in a comfortable little apartment replete with every convenience.

Having donned a warm dressing-gown, I was conducted to the Board Room, where I found a dozen of our [pg 160] greatest Specialists assembled. The President shook hands and greeted me effusively. Then I passed in turn from one Doctor to another, each making, with the utmost delicacy and consideration, a thorough examination of that part of my anatomy on which he was an acknowledged expert.

When this was over I was invited to retire to the dressing-room and resume my garments while the Board held a protracted consultation on my case. On returning to the Board Room I was provided with a seat, and the President addressed me.

"Well, Mr. Smith, we can find nothing constitutionally wrong with you. But tell me, have you ever had any serious illness?"

I shook my head. I had always been abnormally healthy.

"Think carefully," he urged. "We don't want to pass you as fit if we can help it."

He seemed so anxious that I felt ashamed to disappoint him.

"Well," I replied, "the only thing I can call to mind is that, according to my mother, I had a severe teething rash when I was ten months old."

As I uttered these words the faces of all became suddenly grave.

"That is quite enough, Mr. Smith," said the President. "You are given total exemption. You should never have been brought here at all, but I am sure you will realise that in times of national emergency mistakes of this nature are bound to occur. If you will apply to the Cashier on your way out he will give you a draft for twenty pounds, to reimburse you in some small way for the loss of your valuable time. Good-bye!"

He held out his hand, but before I could grasp it a mist again enveloped me, from which I emerged upon the dreadful facts of life.

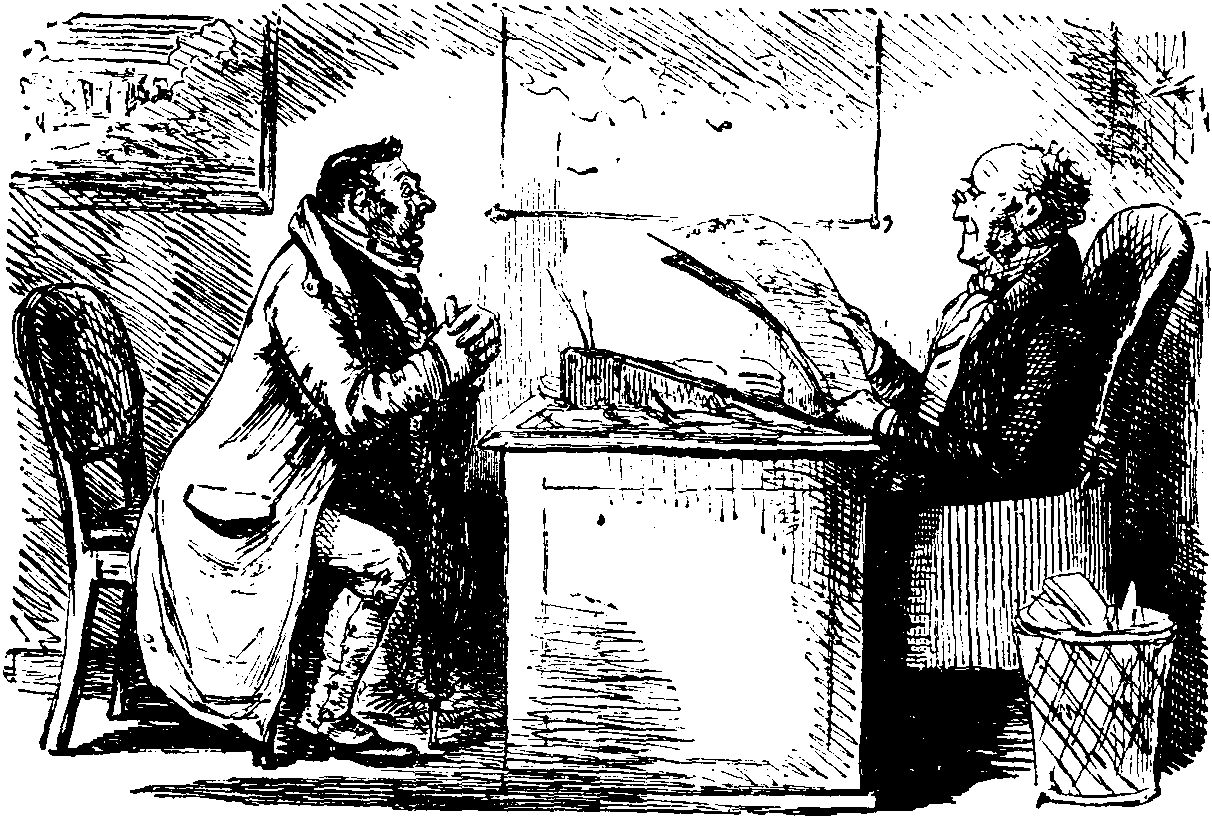

Employer. "WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN?"

Old Operative. "'AVING ME 'AIR CUT."

Employer. "WHAT, IN MY TIME?"

Old Operative. "WELL, IT GREW IN YOUR TIME."

Above three hundred years ago

To Britain's shores there came

An immigrant of lineage low—

Sol Tuberose his name.

He settled down in mean estate,

Despised on every side,

Until at last he waxéd great,

Grew rich and multiplied.

Now none so popular as he;

To every house he goes,

At every table he must be—

The great Sol Tuberose!

In time of war he proves his worth

He helps us everywhere;

There's nothing on (or in) this earth

That can with him compare.

Not the great LLOYD could save the land

Except for mighty Sol;

For he is Bread's twin-brother—and

He gives us Alcohol;

Not such as fills the toper's tum,

But such as fills the shell—

Such as will be in days to come

Heat, light, and pow'r as well.

Yes, in the spacious days to come

We'll bless Sol Tuberose,

When all our motor engines hum

On what the farmer grows.

Then cultivate him all you can,

With him and his stand well in;

There's one that is a Nobleman,

There's one Sir John Llewellyn.

There's one that is a British Queen,

There's one a dwarf, Ashleaf,

There's one that is a plain Colleen,

There's one an Arran Chief.

He'll serve us if we do him well

(Last year he failed our foes).

Oh, who can all the praises tell

Of good Sol Tuberose!

W.B.

"CAPTAIN STANLEY WILSON'S RETURN HOME.

"CHEERFUL AND WELL AFTER LONG INTERMENT."—Yorkshire Post.

"Gentleman, 30, offers 10/- weekly, own laundry, and help with children, refined country home. No needlework."—The Lady.

Slacker!

Letter sent by a soldier's wife to the Army Pay Department:—

"I am sending you my marage sertificate and six children there were seven but won died. You only sent six back her name was fanny and was baptised on a half sheet of paper by the reverend Thomas."

Officer (on leave). "SO YOU'RE STILL ALIVE, PETER?"

Peter. "YES, SIR—AN' I'M GOIN' TO SEE ANOTHER CHRISTMAS, SIR. YOU SEE, SIR, I'VE ALWAYS NOTICED THAT WHEN I LIVE THROUGH THE MONTH OF AUGUST I LIVE OUT THE WHOLE YEAR."

JOHN LEECH, a hundred years ago,

When you were born and after,

There shone a sort of kindly glow

Of airy fun and laughter;

It was a sound that seemed to sing,

A universal humming

That made the echoing rafters ring

And so proclaimed your coming.

It was not noted at the time:

I was not there to note it,

But now I set it down in rhyme

That other men may quote it

And still maintain the thing is true,

Defying Wisdom's strictures,

And lose all doubt by looking through

A book of LEECH'S pictures.

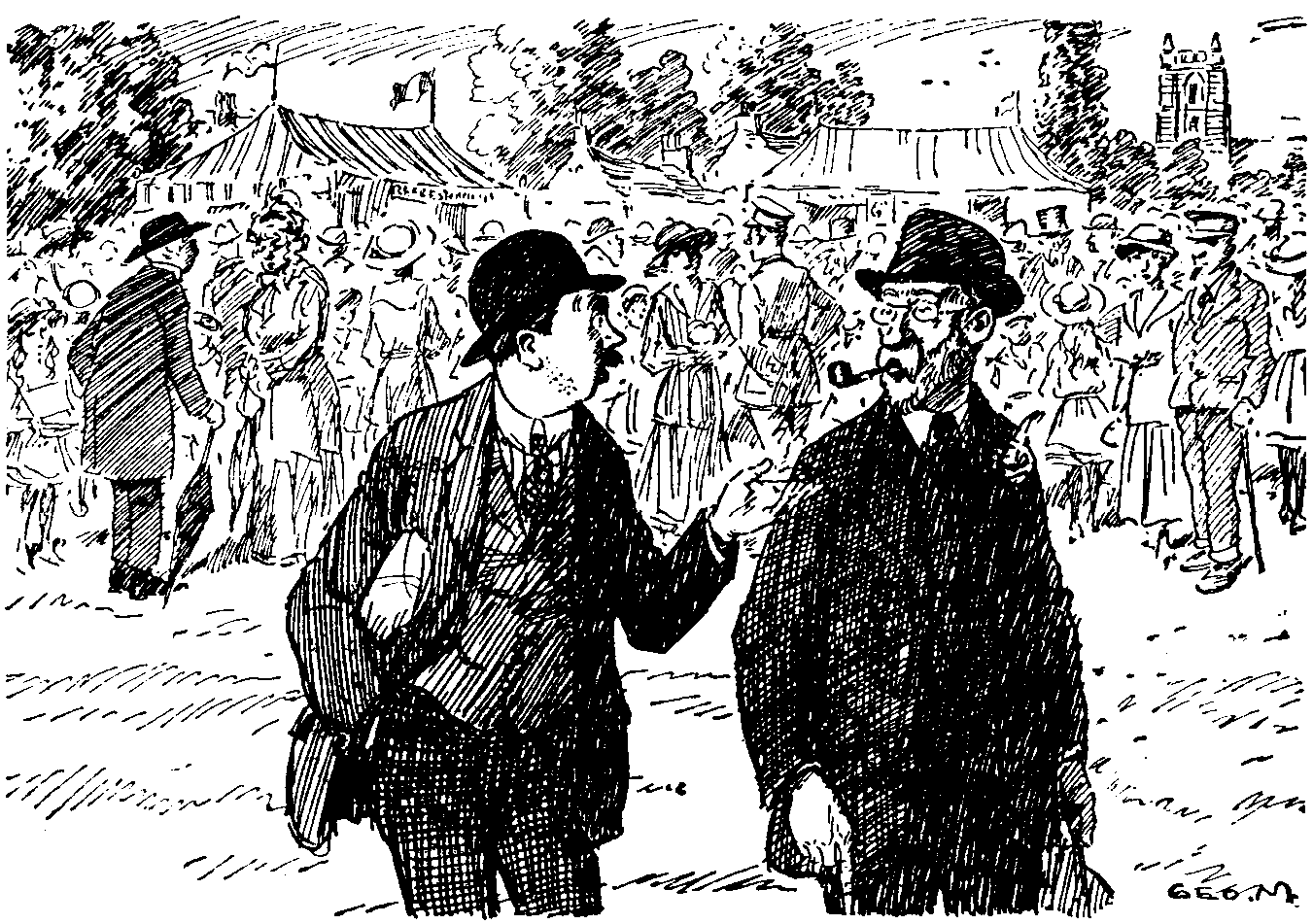

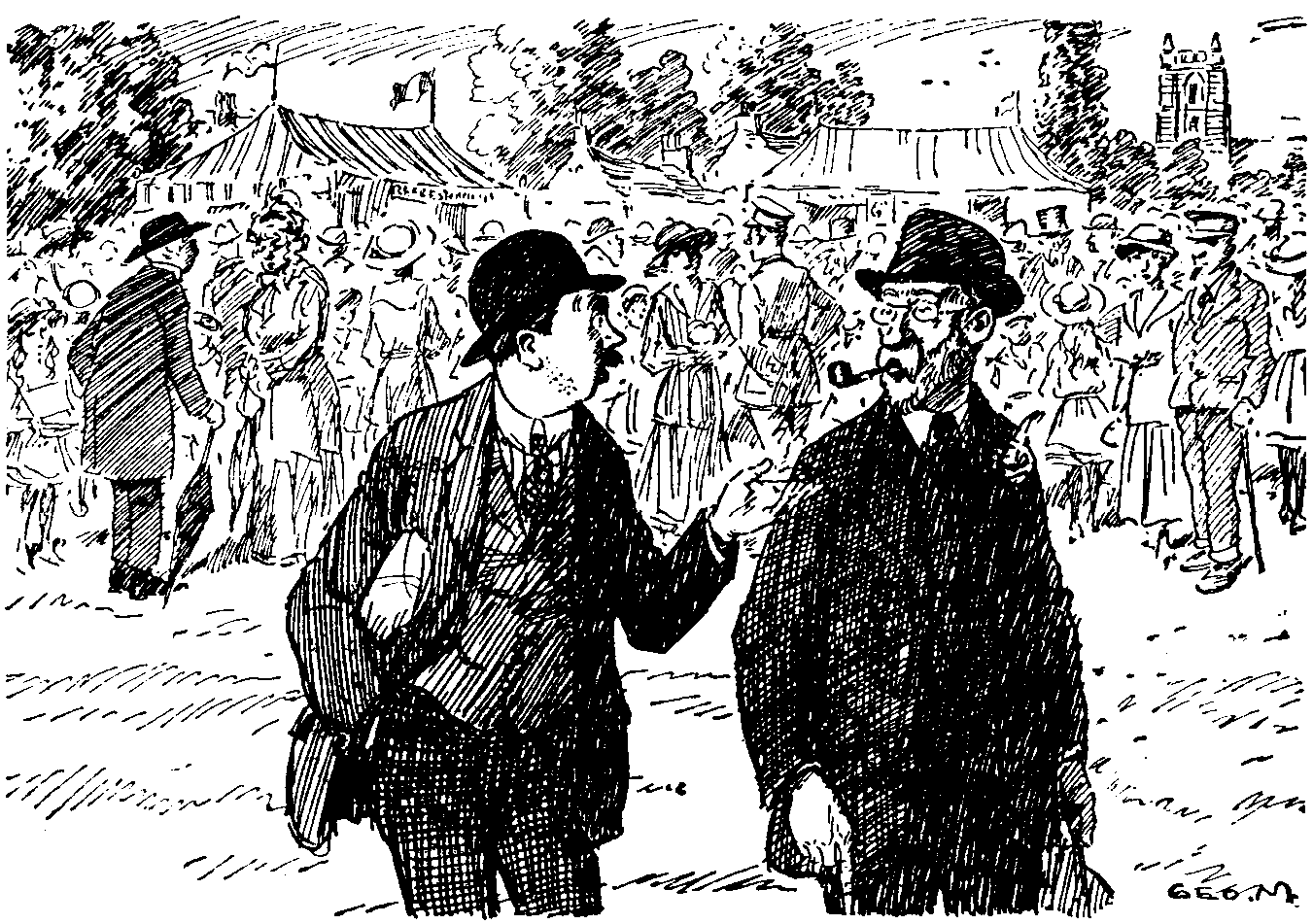

You drew our English country-folk

As many others saw them—

The simple life, the simple joke,

But only you could draw them;

The warp and woof of country joys

In green and pleasant places;

The mischievous and merry boys,

The girls with shining faces.

The Squires, the Centaurs of the chase

And all the chase's patrons,

Each in his own, his ordered place;

The comfortable matrons—

These were your stuff, and these your skill

Consigned to future ages,

And caught and set them down at will

In Mr. Punch's pages.

Besides, you bound us to your praise

With many strong indentures

By limning Mr. Briggs, his ways

And countless misadventures.

For these and many a hundred more,

Far as our voice can reach, Sir,

We send it out from shore to shore,

And bless your name, JOHN LEECH, Sir.

R.C.L.

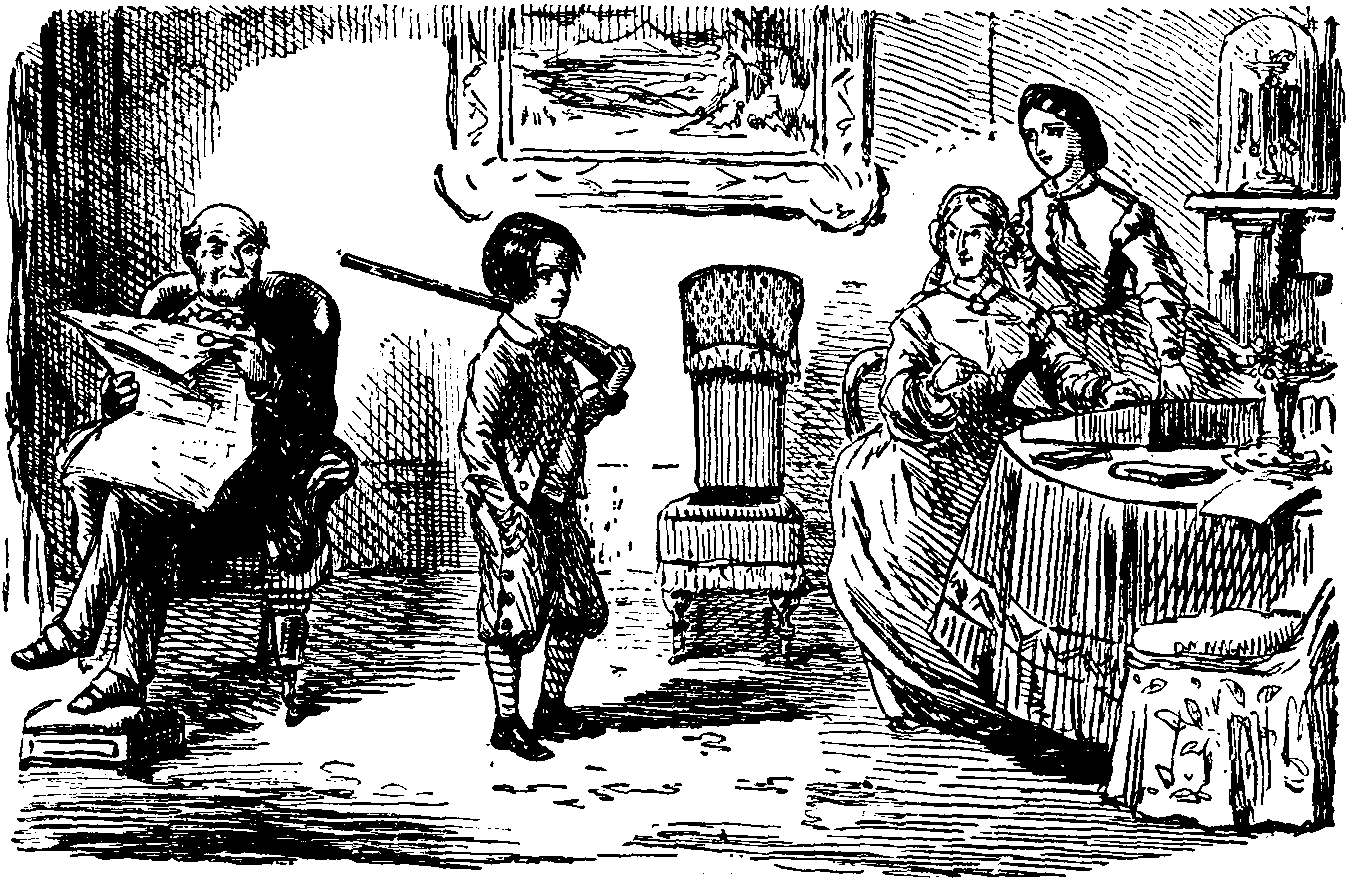

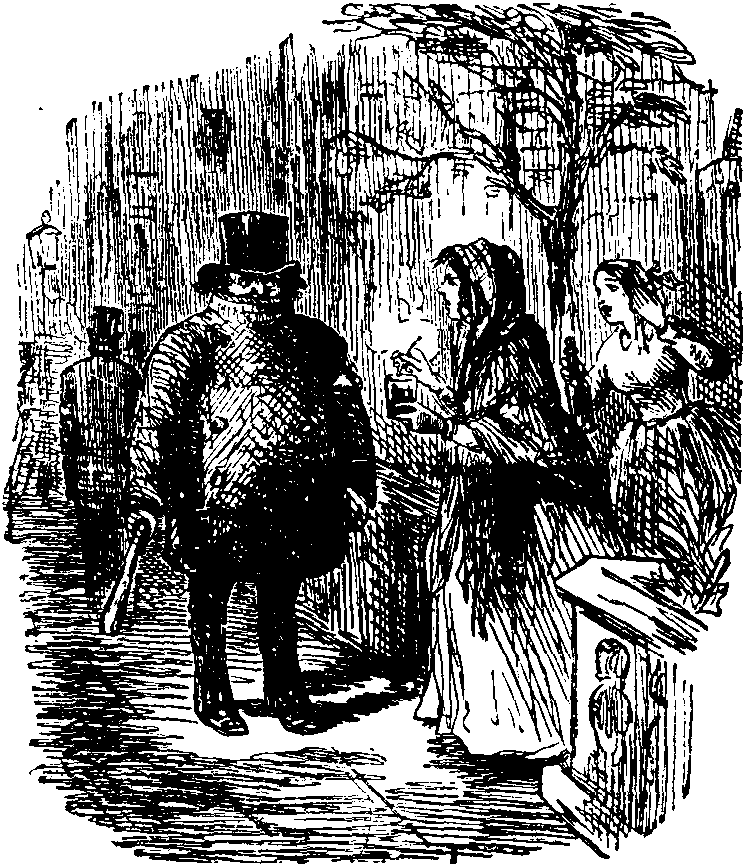

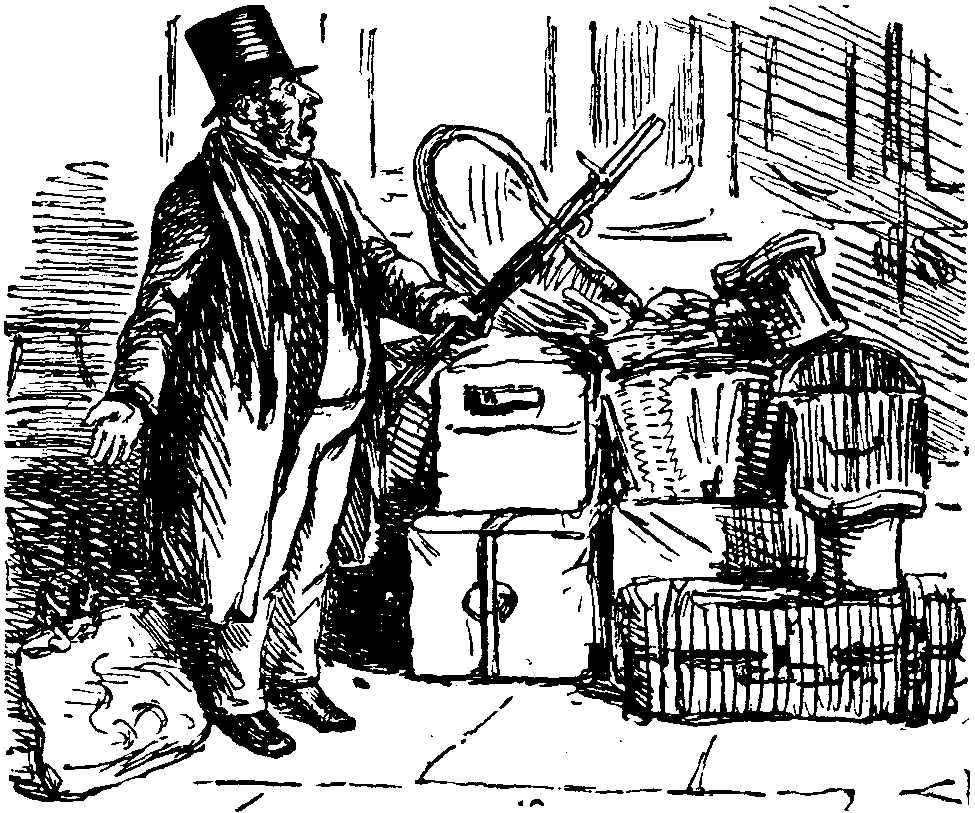

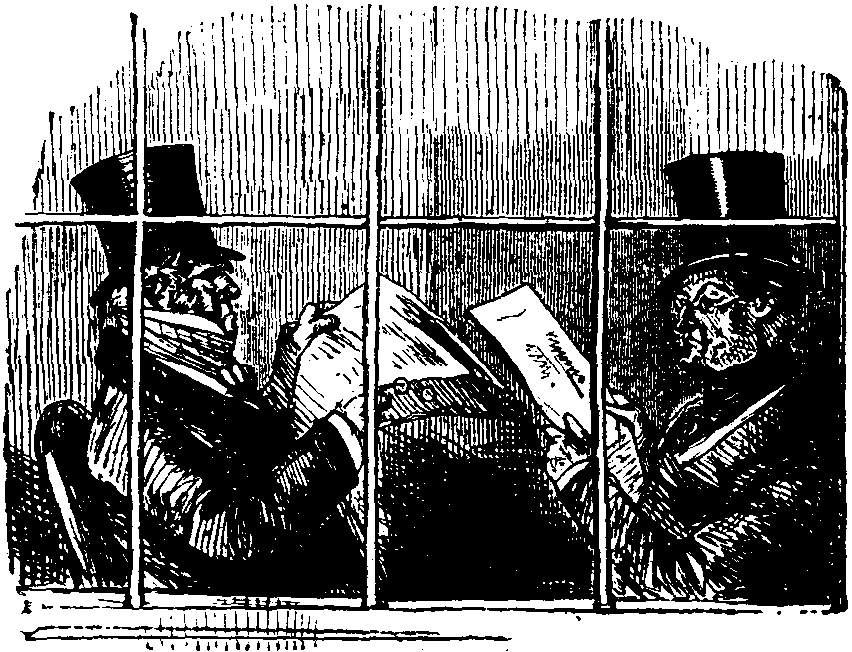

A hundred years ago to the very day was JOHN LEECH born. Mr. Punch came into the world on July 17th, 1841, and was thus twenty-four years younger. But in spite of any disparity in age the two great men were made for each other. JOHN LEECH without Mr. Punch would still have spread delight, for did he not illustrate those Handley Cross novels which his friend THACKERAY said he would rather have written than any of his own books? But to think of Mr. Punch without JOHN LEECH is, as the Irishman said, unthinkable. From the third volume, when LEECH got really into his stride, until his lamented early death in 1864, LEECH'S genius was at the service of his young friend: his quick perceptive kindly eyes ever vigilant for humorous incident, his ears alert for humorous sayings, and his hand translating all into pictorial drama and by a sure and benign instinct seizing always upon the happiest moment.

His three monumental volumes called Pictures of Life and Character constitute a truer history of the English people in the middle of the last century than any author could have composed: history made gay with laughter, but history none the less. And this leaves out of account altogether the artist's work as a cartoonist, where he often exceeded the duty of the historian, and not only recorded the course of events but actually influenced it.

To influence the course of events was however far from being this simple gentleman's ambition. What he chiefly wished was to enable others to share his own enjoyment in the fun and foibles of a world in which it is better to be cheerful than sad, and, in the process of passing on his amusement, to earn a sufficient livelihood to enable him to pay his way and now and then be free to follow the hounds.

All these praises he would probably wish unsaid, so modest and unassuming was he. Let us therefore stop and merely draw attention to the two pages of his drawings which follow, each of which shows JOHN LEECH in the light of a prophet.

Grandmamma. "WHAT CAN YOU WANT, ARTHUR, TO GO BACK TO SCHOOL SO PARTICULARLY ON MONDAY FOR? I THOUGHT YOU WERE GOING TO STAY WITH US TILL THE END OF THE WEEK!"

Arthur. "WHY, YOU SEE, GRAN'MA—WE ARE GOING TO ELECT OFFICERS FOR OUR RIFLE CORPS ON MONDAY, AND I DON'T LIKE TO BE OUT OF IT!" ["Punch," June 30, 1860.

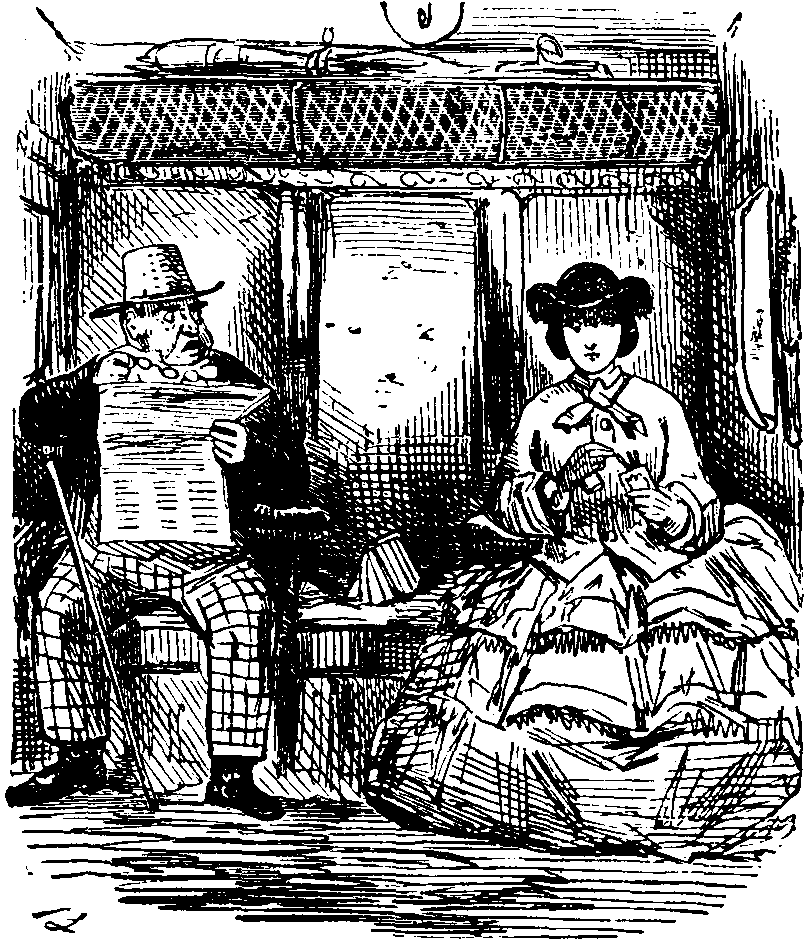

Traveller. "PORTER! PORTER!"

Echo. "DON'T YOU WISH YOU MAY GET HIM?" ["Punch," October 19, 1861.

Old General Muddle. "WHAT I SAY, IS—IS—EH? WHAT? BY JOVE! WHAT THE DOOCE SHOULD CIVILIANS KNOW ABOUT—EH? WHAT—AHEM!—MILITARY AFFAIRS! AFFAIRS! EH?"

Colonel Splutter. "HAH! THE PRESS, SIR! BY JOVE, THE PRESS IS THE CURSE OF THE COUNTRY, AND WILL BE THE RUIN OF THE ARMY! BY JOVE, I'D HANG ALL LITTERY MEN—HANG 'EM, SIR!" ["Punch," February 27, 1858.

Landlord. "WELL, MR. SPRINGWHEAT, ACCORDING TO THE PAPERS, THERE SEEMS TO BE A PROBABILITY OF A CESSATION OF HOSTILITIES."

Tenant (who strongly approves of War prices). "GOODNESS, GRACIOUS! WHY, YOU DON'T MEAN TO SAY THAT THERE'S ANY DANGER OF PEACE!" ["Punch," February 2, 1856.

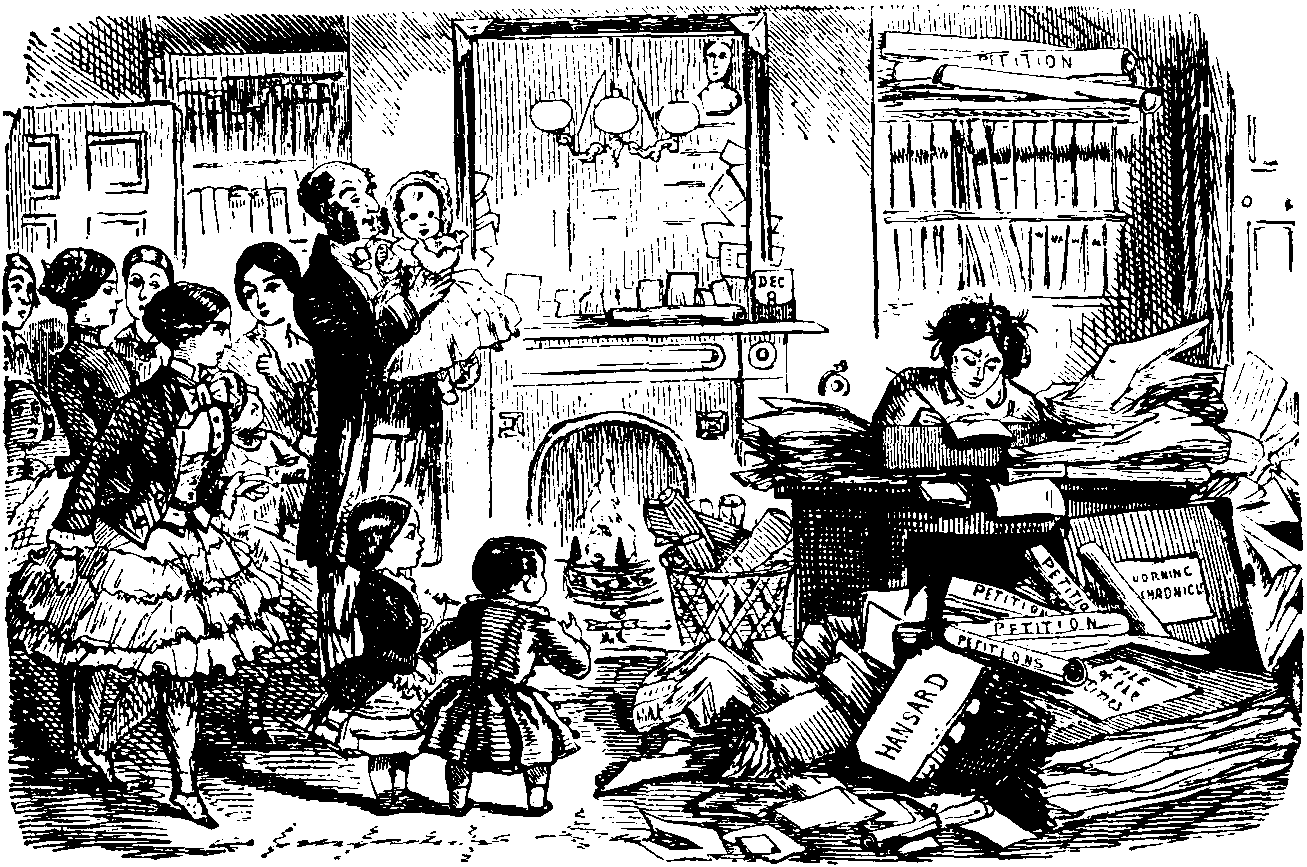

Father of the Family. "COME, DEAR; WE SO SELDOM GO OUT TOGETHER NOW—CAN'T YOU TAKE US ALL TO THE PLAY TO-NIGHT?"

Mistress of the House and M.P. "HOW YOU TALK, CHARLES! DON'T YOU SEE THAT I AM TOO BUSY? I HAVE A COMMITTEE TOMORROW MORNING, AND I HAVE MY SPEECH ON THE GREAT CROCHET QUESTION TO PREPARE FOR THE EVENING." ["Punch's Almanack" for 1853.

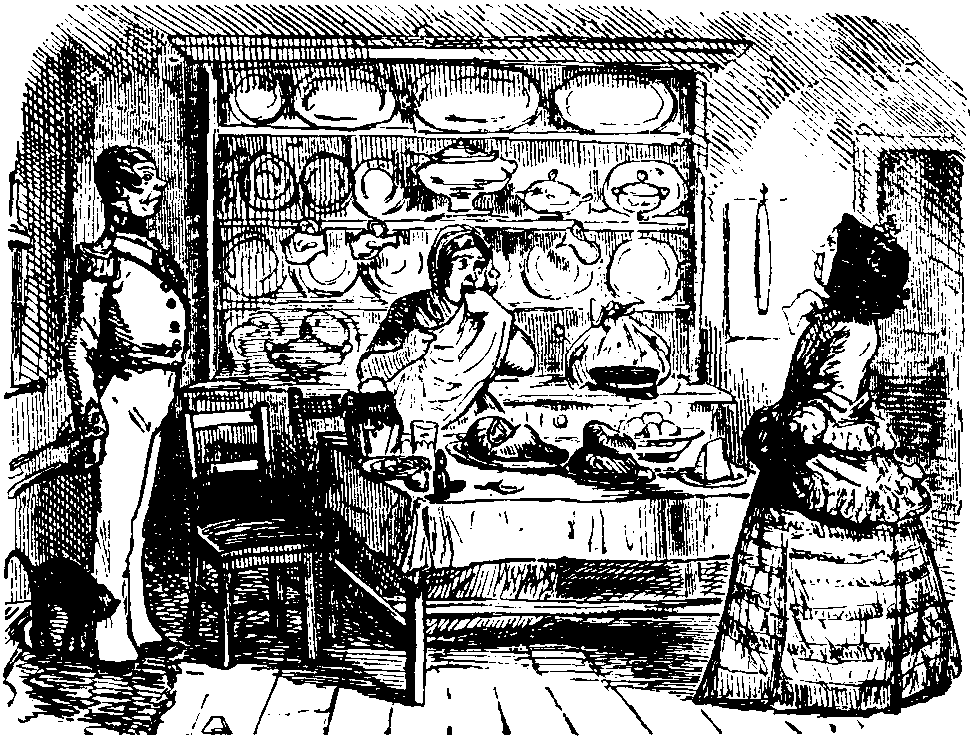

Mistress. "WELL, I'M SURE! AND PRAY WHO IS THAT?"

Cook. "OH, IF YOU PLEASE, 'M, IT'S ONLY MY COUSIN WHO HAS CALLED JUST TO SHOW ME HOW TO BOIL A POTATO." ["Punch," August 31, 1850.

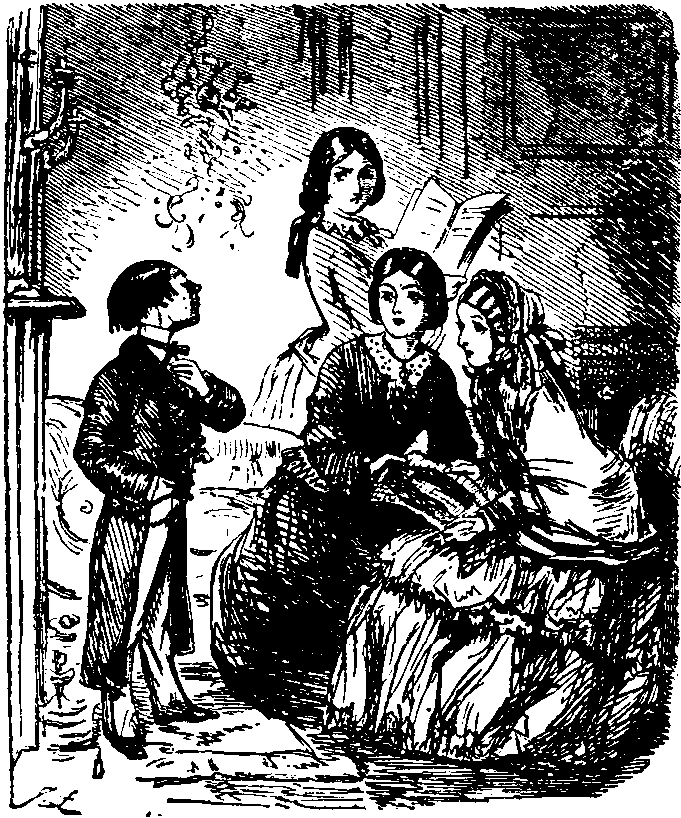

Flora. "OH, I AM SO GLAD—DEAR HARRIET—THERE IS A CHANCE OF PEACE—I AM MAKING THESE SLIPPERS AGAINST DEAR ALFRED COMES BACK!"

Cousin Tom. "HAH, WELL! I AIN'T QUITE SO ANXIOUS ABOUT PEACE—FOR, YOU SEE, SINCE THOSE SOLDIER CHAPS HAVE BEEN ABROAD, WE CIVILIANS HAVE HAD IT PRETTY MUCH OUR OWN WAY WITH THE GURLS!" ["Punch," March 22, 1856.

["Lord Desborough has just been reminding us of the neglected source of food supply that we have in the eels of our rivers and ponds. He stated, 'The food value of an eel is remarkable. In food value one pound of eels is better than a loin of beef.... The greatest eel-breeding establishment in the world is at Comacchio, on the Adriatic. This eel nursery is a gigantic swamp of 140 miles in circumference. It has been in existence for centuries, and in the sixteenth century it yielded an annual revenue of £1,200 to the Pope.'"—Liverpool Daily Post.]

When lowering clouds refuse to lift

And spread depression far and wide,

And when the need of strenuous thrift

Is loudly preached on every side,

What boundless gratitude one feels

To DESBOROUGH, inspiring chief,

For telling us: "One pound of eels

Is better than a loin of beef"

Of old, Popes made eel-breeding pay

(At least Lord DESBOROUGH says they did),

And cleared per annum in this way

Twelve hundred jingling, tingling quid.

In fact my brain in anguish reels

To think we never took a leaf

Out of the book which taught that eels

Are better than prime cuts of beef.

In youth, fastidiously inclined,

I own with shame that I eschewed,

Like most of my unthinking kind,

This luscious and nutritious food;

But now that DESBOROUGH reveals

Its value, with profound belief

I sing with him: "One pound of eels

Is better than a loin of beef."

I chant it loudly in my bath,

I chant it when the sun is high,

And when the moon pursues her path

Noctambulating through the sky.

And when the bill of fare at meals

Is more than usually brief,

Again I sing: "One pound of eels

Is better than a loin of beef."

It is a charm that never fails

When friends accost me in the street

And utter agonizing wails

About the price of butcher's meat.

"Cheer up," I tell them, "creels on creels

Are hastening to your relief;

Cheer up, my friends, one pound of eels

Is better than a loin of beef."

Then all ye fearful folk, dismayed

By threatened shortage of supplies,

Let not your anxious hearts be swayed

By croakers or their dismal cries;

But, from Penzance to Galashiels,

From Abertillery to Crieff,

Remember that "one pound of eels

Is better than a loin of beef."

But these are only pleasant dreams

Unless, to realise our hopes,

Proprietors of ponds and streams

Re-stock them, like the early Popes.

Then, though we still run short of keels

And corn be leaner in the sheaf,

We shall at least have endless eels,

Unnumbered super-loins of beef.

No wonder the Royalty Management, realising how resolutely determined the public was to have nothing to do with anything so witty and workmanlike as The Foundations of Mr. GALSWORTHY, have for their new bill declined upon the pleasantly trivial comedy of errors and tarradiddles, Billeted.

(The happy ending.)

Captain Rymill . . MR. DENNIS EADIE.

Betty Taradine . . MISS IRIS HOEY.

Betty Taradine is billeting at her pretty manor-house a nice vague Colonel. The Vicar's sister disapproves, because Betty is a grass-widow, and Penelope, the all-but-flapper, an insufficient chaperone. She expresses her disapproval with a hardy insolence which must be rare with vicars' sisters in these emancipated times. Naturally when you have a great deal of palaver about Betty's husband having deserted her two years ago after a serious tiff, and no word spoken or written since, you rightly guess that the expected new Adjutant, Captain Rymill, will be none other than the missing man. But you probably don't guess that Betty, to spoof the Church and keep the Colonel, has decided to kill her husband by faked telegram. So you have a distinctly intriguing theme, which Miss TENNYSON JESSE and Captain HARWOOD handle with very considerable adroitness and embroider with many really sparkling and laughter-compelling lines.

I should like to ask the pleasant authors some questions. How is it that the infinitely susceptible Colonel who loves Penelope, but is so overcome by the pseudo-sorrowing Betty that he is afraid of "saying so much more than he means," and appeals to his invaluable Adjutant for help—how is it he survived a bachelor till fifty? And how did Betty, with her abysmal ignorance of pass-book lore, manage to postpone her financial catastrophe for two whole years? And how do they suppose so popular and personable man as Taradine could come back to England under an assumed name without a number of highly inconvenient questions being asked? More seriously, I would ask if they really expect us to believe in the reconciliation on so deep a note of this nice butterfly and this callous husband, who never intended, but for the War, to come back from his big-game shooting, and who took no pains to arrange suitable guidance (there was a lawyer vaguely mentioned but he seems to have been singularly unobtrusive) for the obviously incompetent spouse whom he professes still to love? I am afraid it will not do. The one real point of weakness in the presentation was that Mr. EADIE could not modulate from the key of agreeable flippancy in which the comedy as a whole was set into that of the solemnly sentimental coda. Thus was the artistic unity of a pleasant trifle destroyed.

Mr. DAWSON MILWARD'S clever careful method made the Colonel a very live and plausible figure. Some of his intimate touches were exceedingly adroit. The authors deserve a fair share of the credit. Indeed there was throughout a suggestion of clever characterisation conspicuously above the average of this genre. Penelope was an excellently developed part, rendered with unexpectedly mature skill by Miss STELLA JESSE. The Vicar promised at first to be a new type, but the authors seemed to have lost interest in him half-way, and not even Mr. LAWRENCE HANRAY'S skill and restraint could quite save him. I rate Mr. EADIE as an actor too high to be much amused by him in obviously EADIE parts. "A man's reach must exceed his grasp." I think it just to Miss HOEY to say that she seemed a little handicapped by efforts of memory, a condition which will duly disappear and leave her charm to assert itself. Mr. GEORGE HOWARD was quite admirable as a Scots bank manager; Miss BLANCHE STANLEY, a really sound combination of essential good-nature and wounded dignity as a cook on the verge of giving notice. Miss GERTRUDE STERROLL tackled a vicaress of the Mid-Victorian era (authors' responsibility this) with a courage which deserves both praise and sympathy.

T.

Jack loves dreadnoughts, Peggy loves trains,

But I know what I love—aeroplanes.

Jack will sail the high seas if he can stick it;

Peggy'll be the girl in blue who asks to see your ticket;

But I will steer my aeroplane over London town

And loop the loop till Nurse cries out, "Lor', Master Jim, come down!"

Jack will be an admiral if he isn't sick;

Peggy'll take the tickets and punch them with a click;

But I will make a splendid hum up there in the blue;

I'll look down on London town, I'll look down on you.

Jack will hunt for U-boats and sink the beasts by scores;

Peggy'll have a perfect life, slamming carriage doors;

But I shall join the R.F.C. and Nurse herself will shout,

"There's Master Flight-Commander Jim has put them Huns to rout."

"A well-known Liverpool shipowner and philanthropist is giving £70,000—£100 for each year of his life—to various charitable and philanthropic objects."—Scotsman.

He might almost have lived in the time of the Patriarchs, but we gather that he preferred the days of the profits.

"Often it was impossible to detect the existence of underground works until their occupants opened fire. At one such spot a white hag was displayed, and when our men charily approached a burst of fire met them."—East Anglian Daily Times.

The enemy is evidently up to his old trick—taking cover behind women.

I foresee the appearance, during the next few years, of many regimental handbooks that will record the history at this present visibly and gloriously in the making. One such has already reached me, a second edition of A Brief History of the King's Royal Rifle Corps (WARREN), compiled and edited by Lieut.-General Sir EDWARD HUTTON, K.C.B. It is a book to be bought and treasured by many to whom the record of a fine and famous regiment has become in these last years doubly precious. The moment of its appearance is indeed excellently opportune, from the fact that, in the first place, the K.R.R. was recruited from our brothers across the Atlantic, the 60th Royal Americans (as they were then) having been raised, in 1756, from the colonists in the Eastern States, with a view to retrieving the recent disaster to General BRADDOCK'S troops, and to provide a force that could meet the French and Indians upon equal terms. Thus the Regiment, which its historian modestly calls a typical unit of the British Army, is in its origin another link between the two great English-speaking allies of to-day. It has a record, certainly second to none, from Quebec to Ypres—one that splendidly bears out the words, themselves ringing like steel, of its motto, Celer et Audax. I should add that all profits from the sale of the book will go to "The Ladies' Guild of the King's Royal Rifle Corps." Friends past and present will no doubt see to it that these profits are considerable.

In The Immortal Gamble (A. AND C. BLACK), by A.T. STEWART and C.J. PESHALL, the Acting Commander and [pg 166] Chaplain of H.M.S. Cornwallis describe the part taken by their ship and its gallant complement in the bombardment of Gallipoli and the subsequent landings down to the final evacuation. The account is clear, concise, unemotional, and uncontroversial. As a glimpse rather than a survey of the Dardanelles campaign it strengthens our faith in the spirit of the race without hopelessly undermining our confidence in its intelligence. Beyond the fact that it records deeds of brave men the book has no mission, and its cheerful detachment might not, in the absence of sterner chronicles, be salutary. But as long as there are enough Commissions to publish scathing reports on this or that phase of national ineptitude it is not the publishers' business to provide cathartics for the fatted soul of a self-satisfied people. As the passing of time obliterates the futilities and burnishes the heroisms of the noblest and most forlorn adventure in the history of the race, The Immortal Gamble will find a just place among the simple chronicles of courage which the War is storing up for the inspiration of the generations to come.

I fancy that of late the cinema has somewhat departed from its life-long preoccupation with the cow-boy, otherwise, I should have little hesitation in predicting a great future on the film for Naomi of the Mountains (CASSELL). For this very stirring drama of the wilder West is so packed with what I can't resist calling "reelism" that it is almost impossible to think of it otherwise than in terms of the screen. It is concerned with the wooing, by two contrasted suitors, of Naomi, herself more or less a child of nature, who dwelt in the back-of-beyond with her old, fanatic and extremely unpleasant father. But, though the action is of the breathless type that we have come to expect from such a setting, there is far more character and serious observation than you would be prepared to find. Mr. CHRISTOPHER CULLEY has drawn a real woman, and at least two human and well-observed men. I will not give you in detail the varied course of Naomi's romance, which ends in a perfect orgy of battle, with sheriffs and shooting, redskins and revolvers—in short, all the effects that Mr. HAWTREY not long ago so successfully illustrated on the stage. To sum up, I should describe Naomi of the Mountains as melodrama with a difference—the difference residing in its clever character-drawing and some touches of genuine emotion which lift it above the ordinary. And this from one to whom the Wild West in fiction has long been a weariness is something more than tepid praise.

Sir CHARLES WALDSTEIN, author of the thoughtful Aristodemocracy, is a thinker with an internationalist mind. But pray don't think he's not a whole-hogger about the War. In What Germany is Fighting For (LONGMANS) he analyses the Germans' statement of their war-aims and does good service by presenting an excellent translation, with comment and epilogue, of the famous manifesto of "The Six Associations," and the "Independent Committee for a German Peace." It is an insolent, humourless, immoral document. Anything like it published in England would be laughed out of court by Englishmen. It is difficult to keep one's temper when one reads all this nauseating stuff about the little German lamb being threatened by the wolf, England (or Russia or France, as best suits the current paragraph), and Germany's fine solicitude for the freedom of the seas. It is no disrespect to Sir CHARLES WALDSTEIN that his acute and dispassionate comment is not so forcible an argument to hold us unflinchingly to the essence of our task as any page of the manifesto itself. The German, with all his craft, has an almost unlimited capacity for giving himself away. It would seem that, after all, humour is the best gift of the gods.... Our commentator ends with an epigram to the general effect that "until they adopt, in common with us, the ideal of the Gentleman, in contradistinction to that of the Superman," we must continue to strafe them in war or peace. His book constitutes an important War document.

If I had been compelled to nominate an author to write a book called The Gossip Shop (HODDER AND STOUGHTON) I should have selected Mrs. J.E. BUCKROSE without a moment's hesitation. So I ought to be happy. Anything more soothing to tired nerves than the tittle-tattle of these Wendlebury old ladies it is impossible to imagine. And to add to the lullaby we are given an ancient cab-horse called Griselda, who with a flick of her tail seems to render the atmosphere even more calm and serene. Then there is a love-story which, in spite of misunderstandings, is never really perturbing, and—as a spice—a fortune telling lady who in such respectable society is as near to being naughty as doesn't matter. Small beer? Perhaps. But if you want to get away from the War and rumours of it, I advise you to take a draught of this tranquillizing potion.

From a Booksellers' Catalogue:—

"PLUTARCH: His Life, his Parallel Lives, and his Morals. 3/6."

So spicy a story is surely cheap at the price.

"The cause of the explosion is unknown, but it is assumed that some combustible matter was among the coal."—Daily Dispatch.

It is only fair to some of the coal merchants to say that they take great pains to reduce this danger to a minimum.

"Sugar cargoes amounting to over 40,000 tons have been put down by mines and submarines."—Daily Paper.

Full many a cube of Sparkling Loaf agleam

The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear;

Full many a sack of Crystals melts astream

And wastes its sweetness on the fishes there.