Project Gutenberg's Our Vanishing Wild Life, by William T. Hornaday

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Our Vanishing Wild Life

Its Extermination and Preservation

Author: William T. Hornaday

Release Date: August 22, 2004 [EBook #13249]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OUR VANISHING WILD LIFE ***

Produced by Paul Murray and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

"Hew to the line! Let the chips fall where they will."—Old Exhortation.

"Nothing extenuate, nor set down aught in malice."—Othello.

For the benefit of the cause that this book represents, the author freely extends to all periodicals and lecturers the privilege of reproducing any of the maps and illustrations in this volume except the bird portraits, the white-tailed deer and antelope, and the maps and pictures specially copyrighted by other persons, and so recorded. This privilege does not cover reproductions in books, without special permission.

TO

William Dutcher

FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT OF THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF AUDUBON SOCIETIES, AND

LIFE-LONG CHAMPION OF AMERICAN BIRDS

THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED BY

A SINCERE ADMIRER

"I drink to him, he is not here,

Yet I would guard his glory;

A knight without reproach or fear

Should live in song and story."

—Walsh.

The preservation of animal and plant life, and of the general beauty of Nature, is one of the foremost duties of the men and women of to-day. It is an imperative duty, because it must be performed at once, for otherwise it will be too late. Every possible means of preservation,—sentimental, educational and legislative,—must be employed.

The present warning issues with no uncertain sound, because this great battle for preservation and conservation cannot be won by gentle tones, nor by appeals to the aesthetic instincts of those who have no sense of beauty, or enjoyment of Nature. It is necessary to sound a loud alarm, to present the facts in very strong language, backed up by irrefutable statistics and by photographs which tell no lies, to establish the law and enforce it if needs be with a bludgeon.

This book is such an alarm call. Its forceful pages remind me of the sounding of the great bells in the watch-towers of the cities of the Middle Ages which called the citizens to arms to protect their homes, their liberties and their happiness. It is undeniable that the welfare and happiness of our own and of all future generations of Americans are at stake in this battle for the preservation of Nature against the selfishness, the ignorance, or the cruelty of her destroyers.

We no longer destroy great works of art. They are treasured, and regarded as of priceless value; but we have yet to attain the state of civilization where the destruction of a glorious work of Nature, whether it be a cliff, a forest, or a species of mammal or bird, is regarded with equal abhorrence. The whole earth is a poorer place to live in when a colony of exquisite egrets or birds of paradise is destroyed in order that the plumes may decorate the hat of some lady of fashion, and ultimately find their way into the rubbish heap. The people of all the New England States are poorer when the ignorant whites, foreigners, or negroes of our southern states destroy the robins and other song birds of the North for a mess of pottage.

Travels through Europe, as well as over a large part of the North American continent, have convinced me that nowhere is Nature being destroyed so rapidly as in the United States. Except within our conservation areas, an earthly paradise is being turned into an earthly hades; and it is not savages nor primitive men who are doing this, but men and women who boast of their civilization. Air and water are polluted, rivers and streams serve as sewers and dumping grounds, forests are swept away and fishes are driven from the streams. Many birds are becoming extinct, and certain mammals are on the verge of [Page†viii] extermination. Vulgar advertisements hide the landscape, and in all that disfigures the wonderful heritage of the beauty of Nature to-day, we Americans are in the lead.

Fortunately the tide of destruction is ebbing, and the tide of conservation is coming in. Americans are practical. Like all other northern peoples, they love money and will sacrifice much for it, but they are also full of idealism, as well as of moral and spiritual energy. The influence of the splendid body of Americans and Canadians who have turned their best forces of mind and language into literature and into political power for the conservation movement, is becoming stronger every day. Yet we are far from the point where the momentum of conservation is strong enough to arrest and roll back the tide of destruction; and this is especially true with regard to our fast vanishing animal life.

The facts and figures set forth in this volume will astonish all those lovers of Nature and friends of the animal world who are living in a false or imaginary sense of security. The logic of these facts is inexorable. As regards our birds and mammals, the failures of supposed protection in America—under a system of free shooting—are so glaring that we are confident this exposure will lead to sweeping reforms. The author of this work is no amateur in the field of wild-life protection. His ideas concerning methods of reform are drawn from long and successful experience. The states which are still behind in this movement may well give serious heed to his summons, and pass the new laws that are so urgently demanded to save the vanishing remnant.

The New York Zoological Society, which is cooperating with many other organizations in this great movement, sends forth this work in the belief that there is no one who is more ardently devoted to the great cause or rendering more effective service in it than William T. Hornaday. We believe that this is a great book, destined to exert a world-wide influence, to be translated into other languages, and to arouse the defenders and lovers of our vanishing animal life before it is too late.

|

HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN, |

|

|

10 December, 1912. |

President of the New York Zoological Society |

The writing of this book has taught me many things. Beyond question, we are exterminating our finest species of mammals, birds and fishes according to law!

I am appalled by the mass of evidence proving that throughout the entire United States and Canada, in every state and province, the existing legal system for the preservation of wild life is fatally defective. There is not a single state in our country from which the killable game is not being rapidly and persistently shot to death, legally or illegally, very much more rapidly than it is breeding, with extermination for the most of it close in sight. This statement is not open to argument; for millions of men know that it is literally true. We are living in a fool's paradise.

The rage for wild-life slaughter is far more prevalent to-day throughout the world than it was in 1872, when the buffalo butchers paved the prairies of Texas and Colorado with festering carcasses. From one end of our continent to the other, there is a restless, resistless desire to "kill, kill!"

I have been shocked by the accumulation of evidence showing that all over our country and Canada fully nine-tenths of our protective laws have practically been dictated by the killers of the game, and that in all save a very few instances the hunters have been exceedingly careful to provide "open seasons" for slaughter, as long as any game remains to kill!

And yet, the game of North America does not belong wholly and exclusively to the men who kill! The other ninety-seven per cent of the People have vested rights in it, far exceeding those of the three per cent. Posterity has claims upon it that no honest man can ignore.

I am now going to ask both the true sportsman and the people who do not kill wild things to awake, and do their plain duty in protecting and preserving the game and other wild life which belongs partly to us, but chiefly to those who come after us. Can they be aroused, before it is too late?

The time to discuss tiresome academic theories regarding "bag limits" and different "open seasons" as being sufficient to preserve the game, has gone by! We have reached the point where the alternatives are long closed seasons or a gameless continent; and we must choose one or the other, speedily. A continent without wild life is like a forest with no leaves on the trees.

[Page†x]The great increase in the slaughter of song birds for food, by the negroes and poor whites of the South, has become an unbearable scourge to our migratory birds,—the very birds on which farmers north and south depend for protection from the insect hordes,—the very birds that are most near and dear to the people of the North. Song-bird slaughter is growing and spreading, with the decrease of the game birds! It is a matter that requires instant attention and stern repression. At the present moment it seems that the only remedy lies in federal protection for all migratory birds,—because so many states will not do their duty.

We are weary of witnessing the greed, selfishness and cruelty of "civilized" man toward the wild creatures of the earth. We are sick of tales of slaughter and pictures of carnage. It is time for a sweeping Reformation; and that is precisely what we now demand.

I have been a sportsman myself; but times have changed, and we must change also. When game was plentiful, I believed that it was right for men and boys to kill a limited amount of it for sport and for the table. But the old basis has been swept away by an Army of Destruction that now is almost beyond all control. We must awake, and arouse to the new situation, face it like men, and adjust our minds to the new conditions. The three million gunners of to-day must no longer expect or demand the same generous hunting privileges that were right for hunters fifty years ago, when game was fifty times as plentiful as it is now and there was only one killer for every fifty now in the field.

The fatalistic idea that bag-limit laws can save the game is to-day the curse of all our game birds, mammals and fishes! It is a fraud, a delusion and a snare. That miserable fetish has been worshipped much too long. Our game is being exterminated, everywhere, by blind insistence upon "open seasons," and solemn reliance upon "legal bag-limits." If a majority of the people of America feel that so long as there is any game alive there must be an annual two months or four months open season for its slaughter, then assuredly we soon will have a gameless continent.

The only thing that will save the game is by stopping the killing of it! In establishing and promulgating this principle, the cause of wild-life protection greatly needs three things: money, labor, and publicity. With the first, we can secure the second and third. But can we get it,—and get it in time to save?

This volume is in every sense a contribution to a Cause; and as such it ever will remain. I wish the public to receive it on that basis. So much important material has drifted straight to it from other hands that this unexpected aid seems to the author like a good omen.

The manuscript has received the benefit of a close and critical reading and correcting by my comrade on the firing-line and esteemed friend, Mr. Madison Grant, through which the text was greatly improved. But for the splendid encouragement and assistance that I have received from him and [Page†xi] from Professor Henry Fairneld Osborn the work involved would have borne down rather heavily.

The four chapters embracing the "New Laws Needed; A Roll-Call of the States," were critically inspected, corrected and brought down to date by Dr. T.S. Palmer, our highest authority on the game laws of the Nation and the States. For this valuable service the author is deeply grateful. Of course the author is alone responsible for all the opinions and conclusions herein recorded, and for all errors that appear outside of quotations.

I trust that the Reader will kindly excuse and forget all the typographic and clerical errors that may have escaped me in the rush that had to be made against Time.

|

University Heights, New York, |

W.T.H. |

|

December 1, 1912. |

|

Part I.—Extermination |

||

|

Chapter |

Page |

|

|

I. |

Former Abundance Of Wild Life |

|

|

II. |

Extinct Species Of North American Birds |

|

|

III. |

The Next Candidates For Oblivion |

|

|

IV. |

Extinct And Nearly Extinct Species Of Mammals |

|

|

V. |

The Extermination Of Species, State By State |

|

|

VI. |

The Regular Army Of Destruction |

|

|

VII. |

The Guerrillas Of Destruction |

|

|

VIII. |

The Unseen Foes Of Wild Life |

|

|

IX. |

Destruction Of Wild Life By Diseases |

|

|

X. |

Destruction Of Wild Life By The Elements |

|

|

XI. |

Slaughter Of Song-Birds By Italians |

|

|

XII. |

Destruction Of Song-Birds By Southern Negroes And Poor Whites |

|

|

XIII. |

Extermination Of Birds For Women's Hats |

|

|

XIV. |

The Bird Tragedy On Laysan Island |

|

|

XV. |

Unfair Firearms And Shooting Ethics |

|

|

XVI. |

The Present And Future Of North American Big Game—I |

|

|

XVII. |

The Present And Future Of North American Big Game—II |

|

|

XVIII. |

The Present And Future Of African Game |

|

|

XIX. |

The Present And Future Of Game In Asia |

|

|

XX. |

Destruction Of Birds In The Far East. By C. William Beebe |

|

|

XXI. |

The Savage Viewpoint Of The GunneR |

|

|

Part II.—Preservation |

||

|

XXII. |

Our Annual Losses By Insects |

|

|

XXIII. |

The Economic Value Of Birds |

|

|

XXIV. |

Game And Agriculture: Deer As A Food Supply |

[Page†xiii] |

|

XXV. |

Law And Sentiment As Factors In Preservation |

|

|

XXVI. |

The Army Of The Defense |

|

|

XXVII. |

How To Make A New Game Law |

|

|

XXVIII. |

New Laws Needed: A Roll-Call Of The States—I |

|

|

XXIX. |

New Laws Needed: A Roll-Call Of The States—II |

|

|

XXX. |

New Laws Needed: A Roll-Call Of The States—III |

|

|

XXXI. |

New Laws Needed: A Roll-Call Of The States—IV |

|

|

XXXII. |

Need For A Federal Migratory Bird Law, No-Sale-Of-Game Law, And Others |

|

|

XXXIII. |

Bringing Back The Vanished Birds And Game |

|

|

XXXIV. |

Introduced Species That Have Been Beneficial |

|

|

XXXV. |

Introduced Species That Have Become Pests |

|

|

XXXVI. |

National And State Game Preserves And Bird Refuges |

|

|

XXXVII. |

Game Preserves And Game Laws In Canada |

|

|

XXXVIII. |

Private Game Preserves |

|

|

XXXIX. |

British Game Preserves In Africa |

|

|

XXL. |

Breeding Game And Fur In Captivity |

|

|

XLI. |

Teaching Wild-Life Protection To The Young |

|

|

XLII. |

Ethics Of Sportsmanship |

|

|

XLIII. |

The Duty Of American Zoologists To American Wild Life |

|

|

XLIV. |

The Greatest Need Of The Cause; And The Duty Of The Hour |

|

|

ILLUSTRATIONS [Page†xiv] |

||

|

The Folly of 1857 and the Lesson of 1912 |

||

|

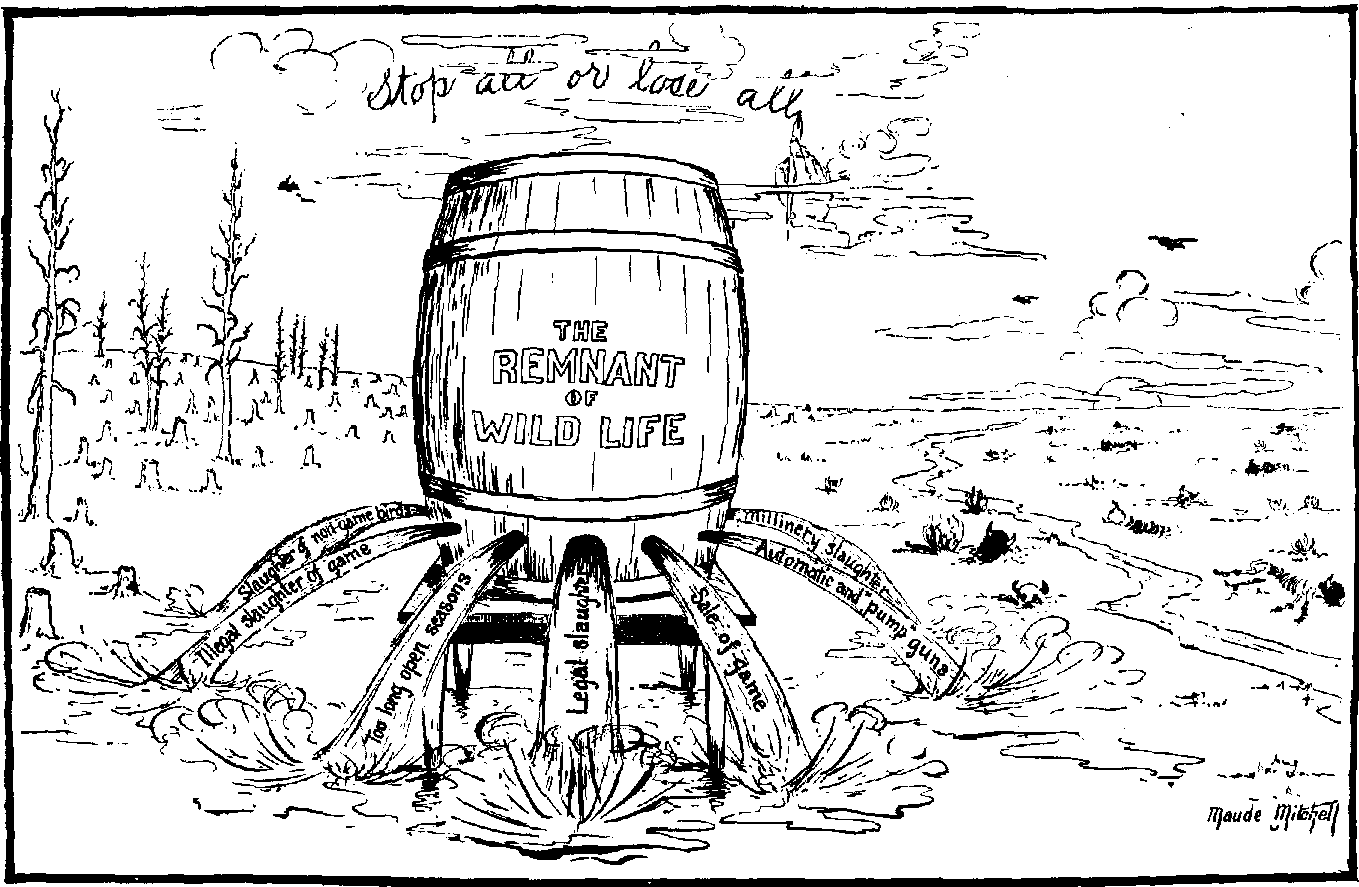

Shall We Leave Any One of Them Open? |

||

|

Six Recently Exterminated North American Birds |

||

|

Sacred to the Memory of Exterminated Birds |

||

|

Whooping Cranes in the Zoological Park |

||

|

California Condor |

||

|

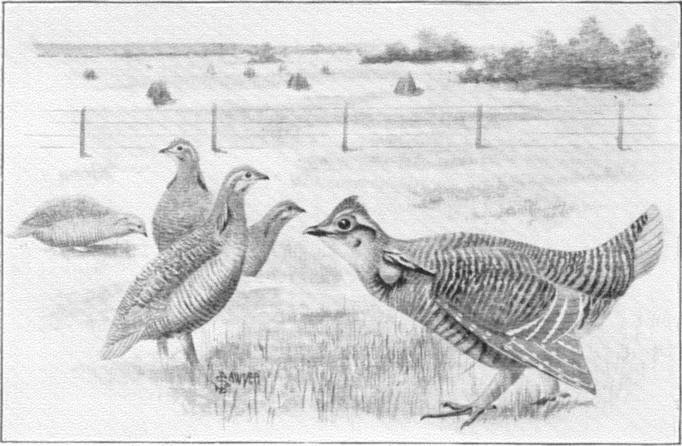

Primated Grouse, or "Prairie Chicken" |

||

|

Sage Grouse |

||

|

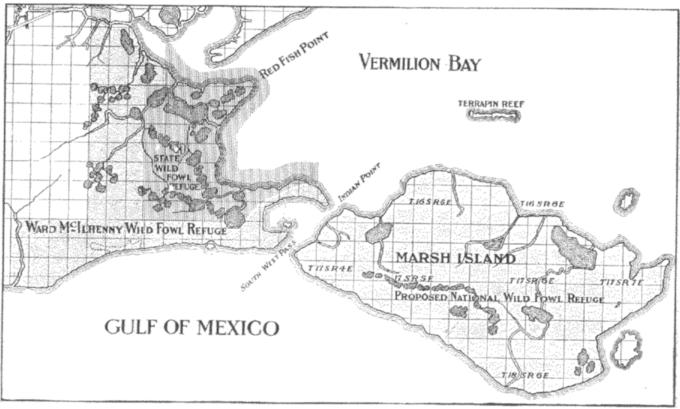

Snowy Egrets in the McIlhenny Preserve |

||

|

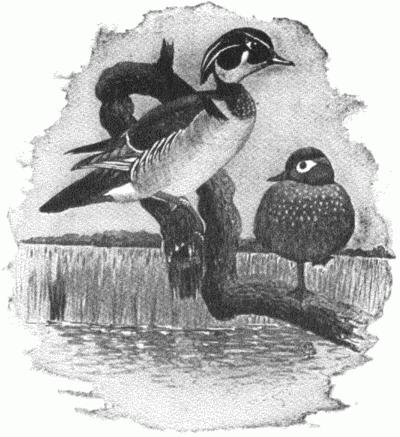

Wood-Duck |

||

|

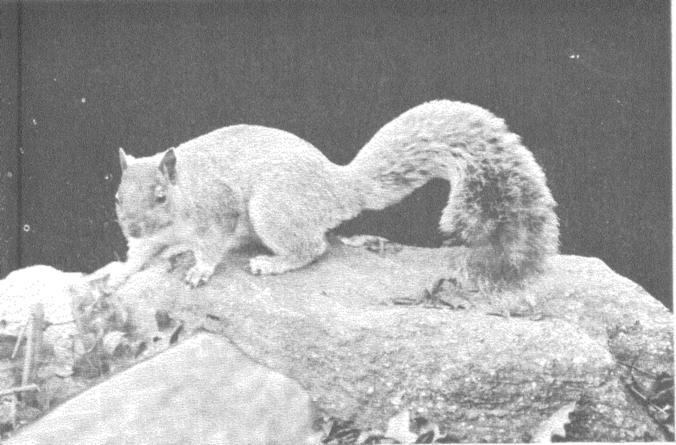

Gray Squirrel |

||

|

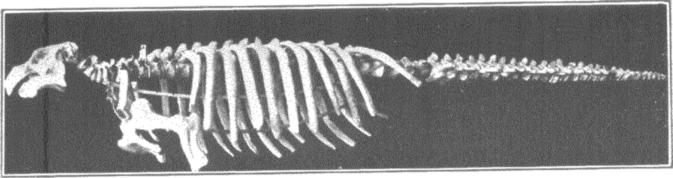

Skeleton of a Rhytina |

||

|

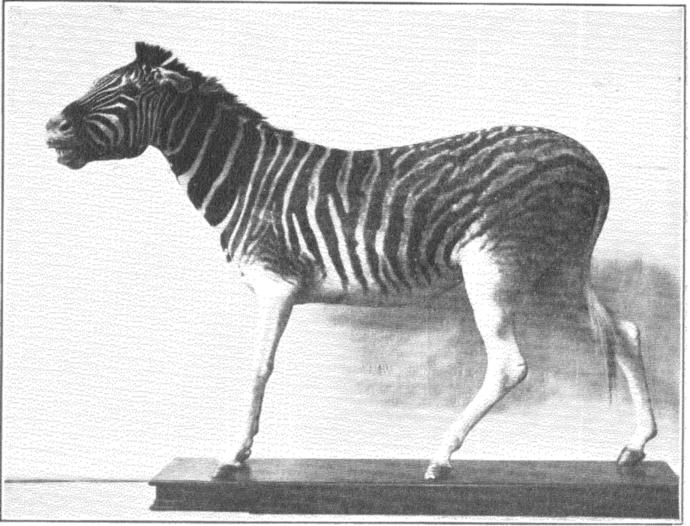

Burchell's Zebra |

||

|

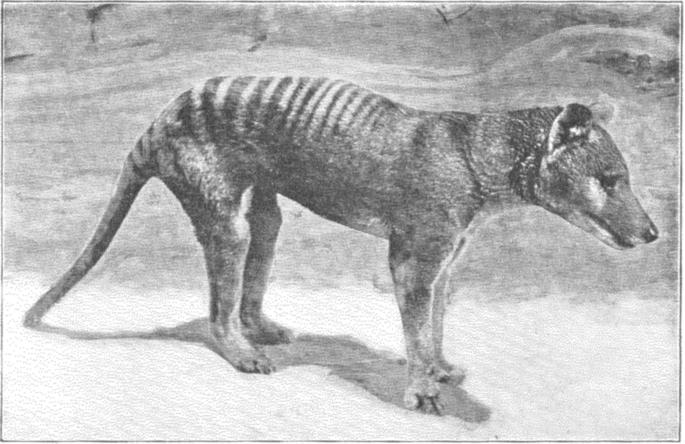

Thylacine, or Tasmanian Wolf |

||

|

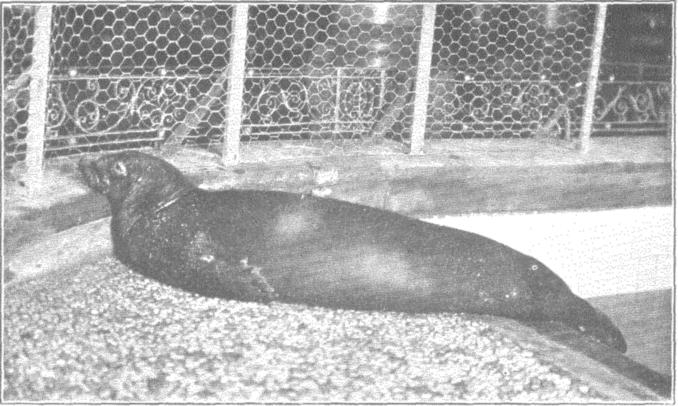

West Indian Seal |

||

|

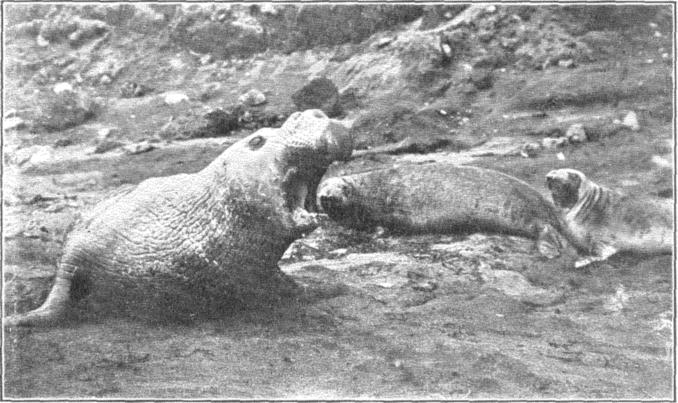

California Elephant Seal |

||

|

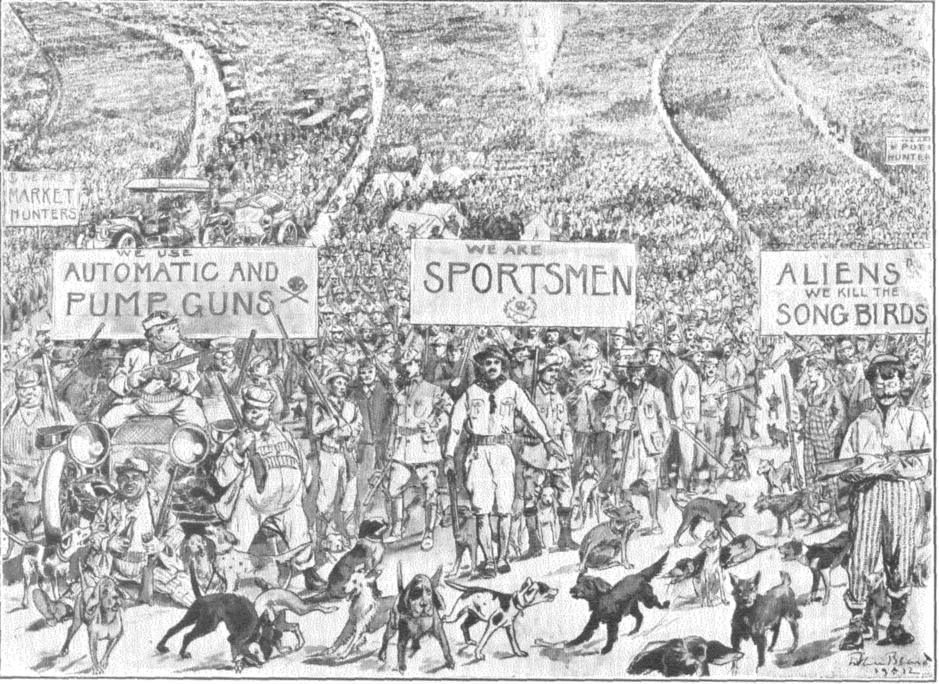

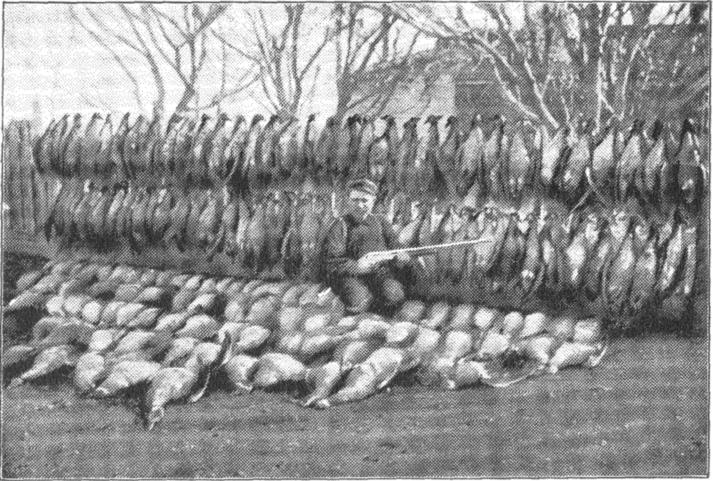

The Regular Army of Destruction |

||

|

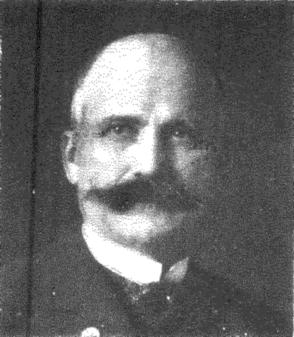

G.O. Shields |

||

|

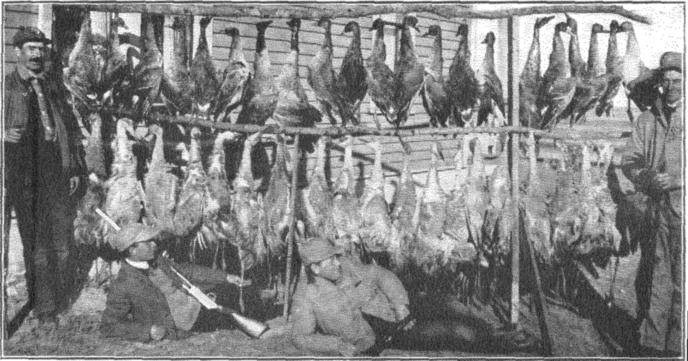

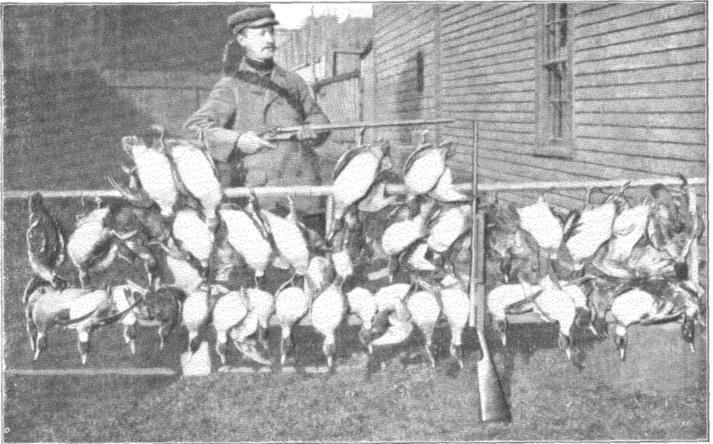

Two Gunners of Kansas City |

||

|

Why the Sandhill Crane is Becoming Extinct |

||

|

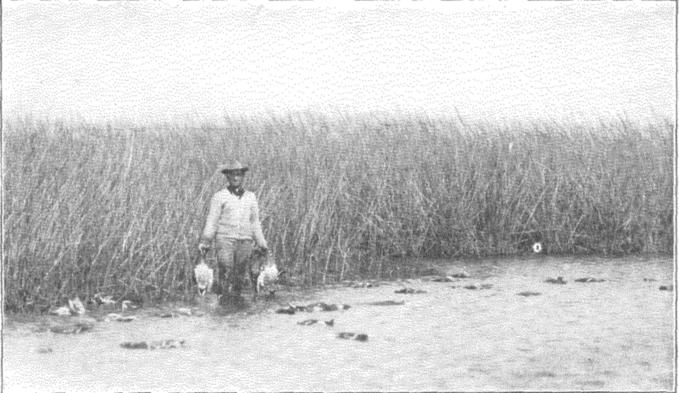

A Market Gunner at Work on Marsh Island |

||

|

Ruffed Grouse |

||

|

A Lawful Bag of Ruffed Grouse |

||

|

Snow Bunting |

||

|

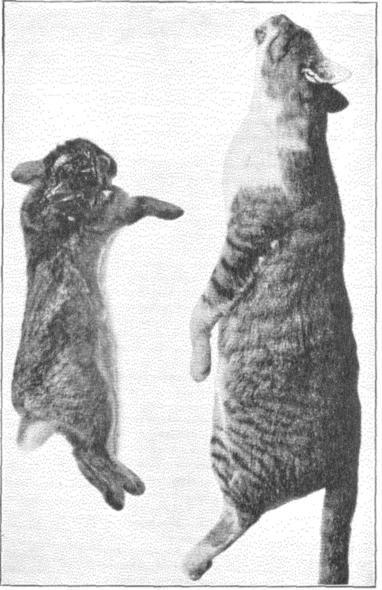

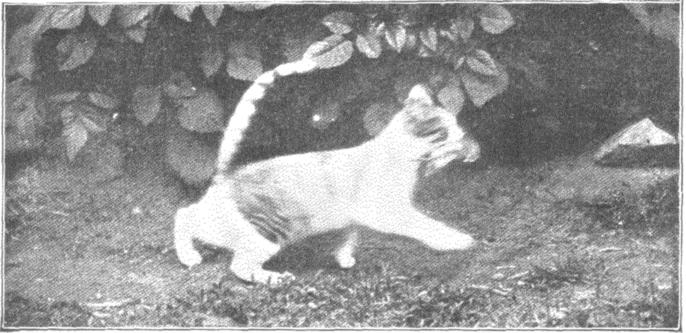

A Hunting Cat and Its Victim |

||

|

Eastern Red Squirrel |

||

|

Cooper's Hawk |

||

|

Sharp-Shinned Hawk |

||

|

The Cat that Killed Fifty-eight Birds in One Year |

||

|

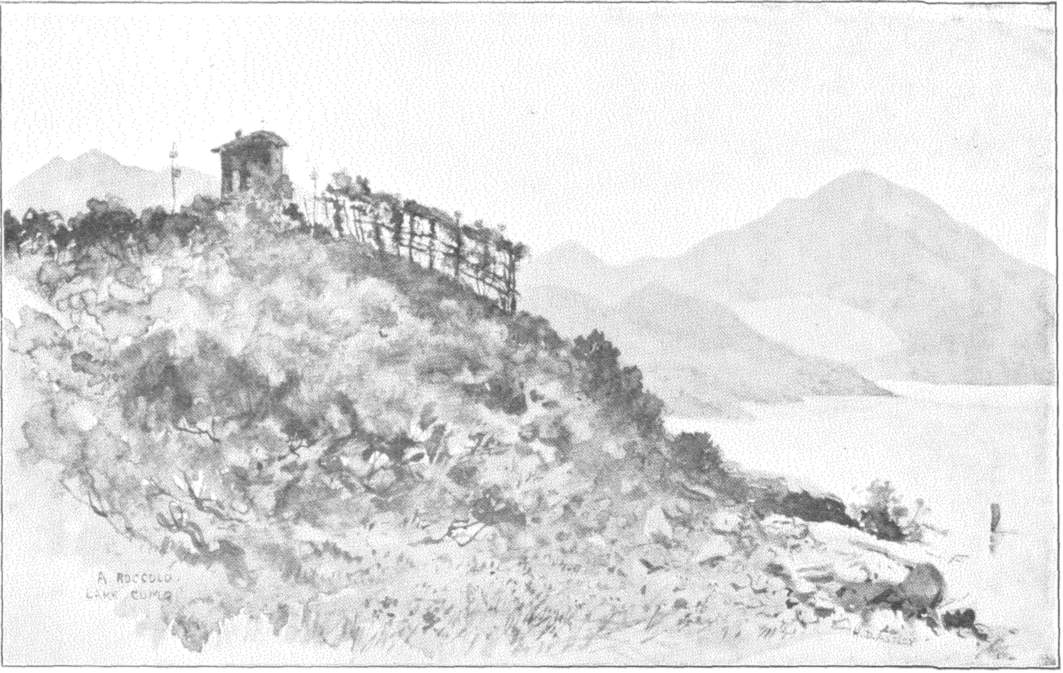

An Italian Roccolo on Lake Como |

||

|

Dead Song-Birds |

||

|

The Robin of the North |

||

|

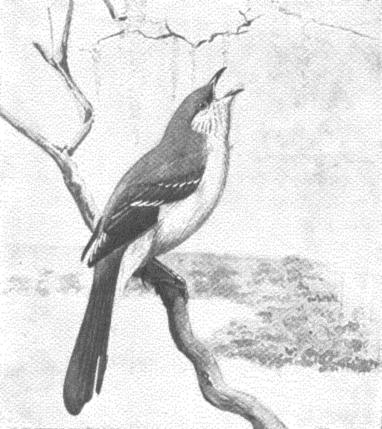

The Mocking-Bird of the South |

||

|

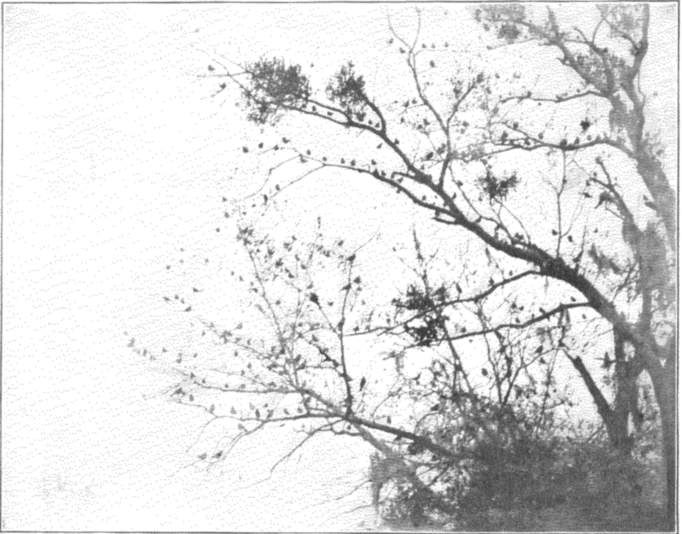

Northern Robins Ready for Southern Slaughter |

||

|

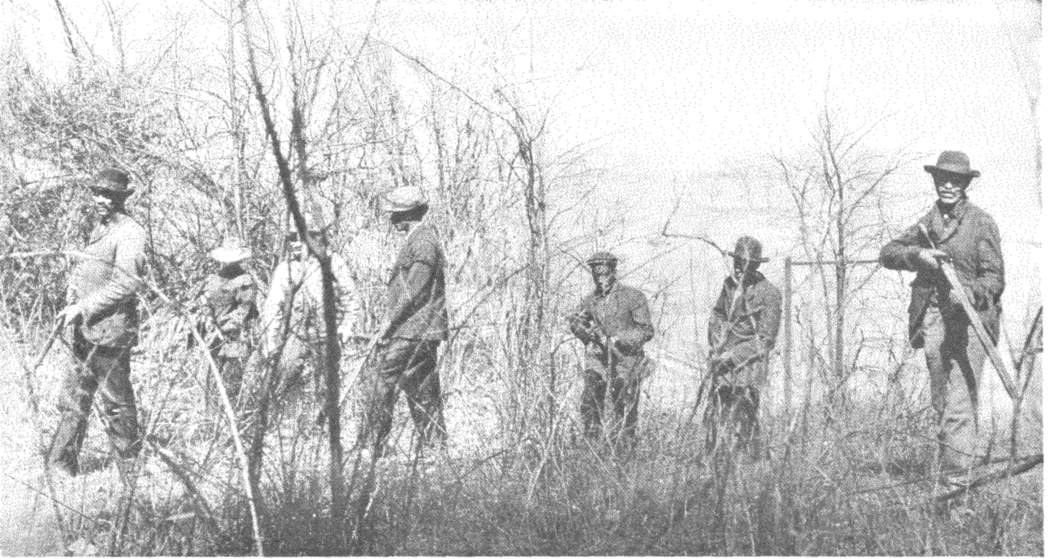

Southern-Negro Method of Combing Out the Wild Life |

||

|

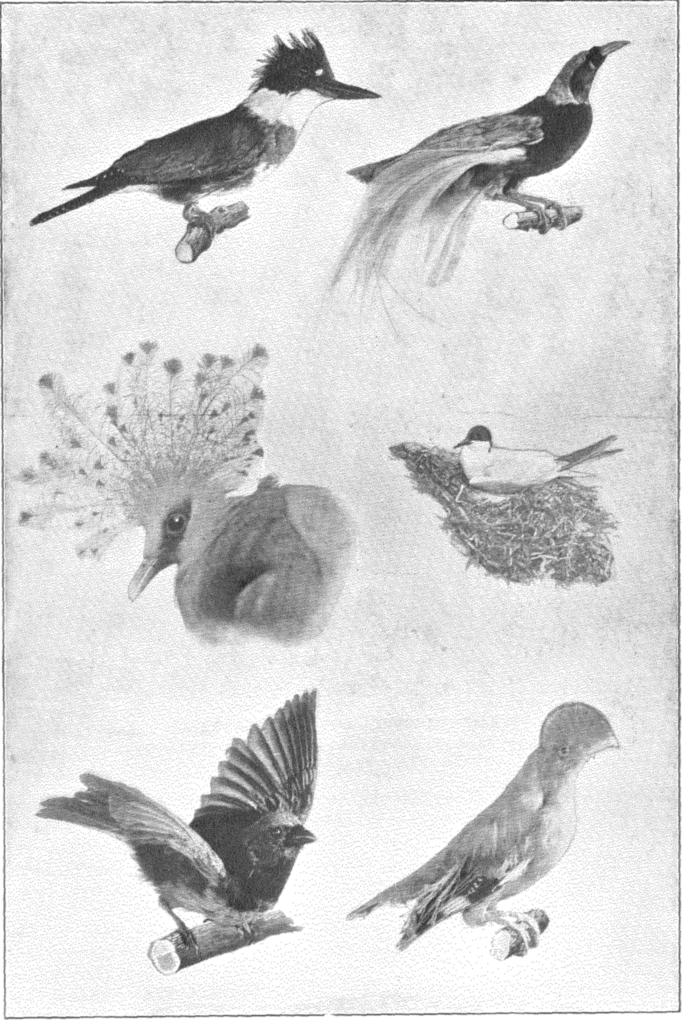

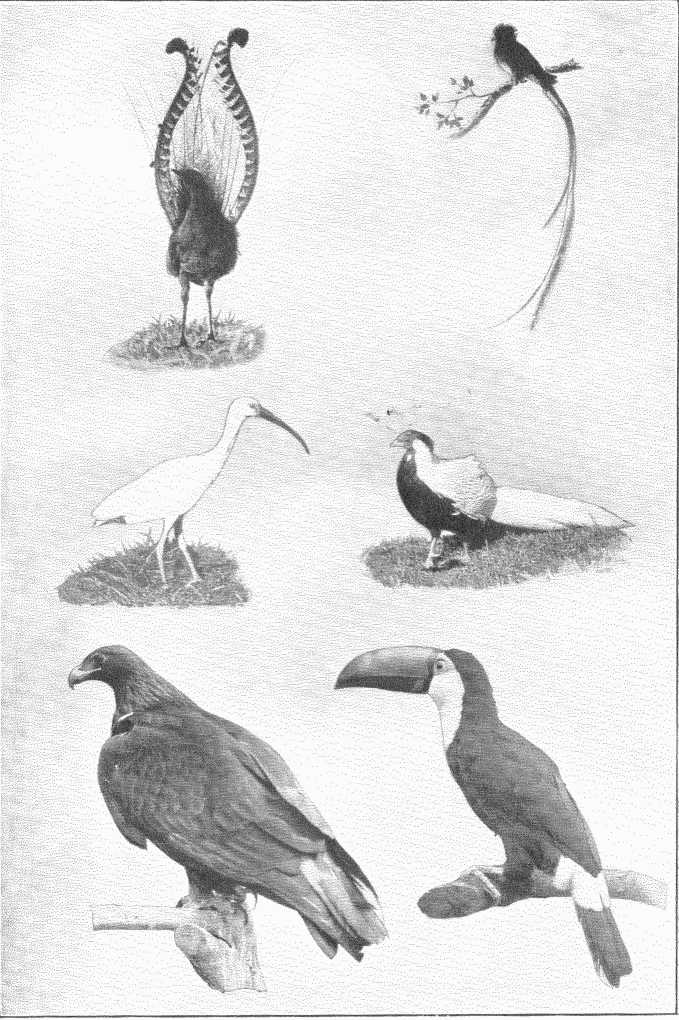

Beautiful and Curious Birds Destroyed for the Feather Trade—I |

||

|

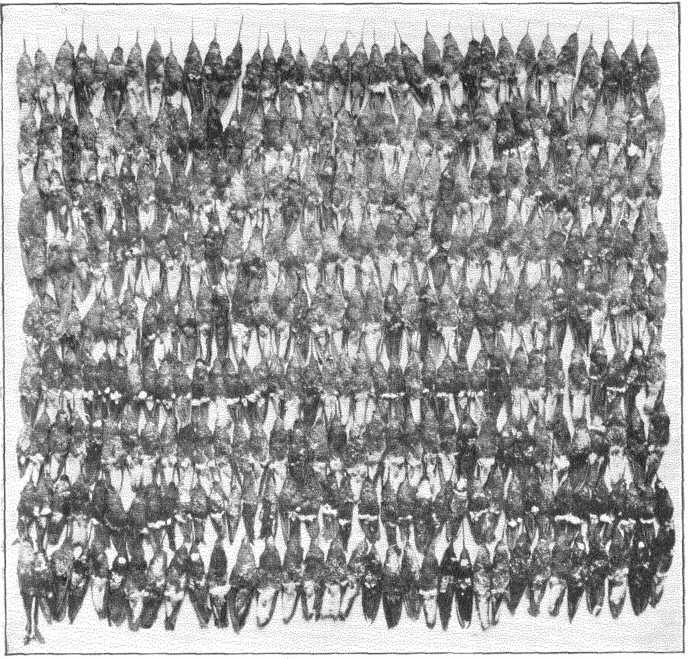

Sixteen Hundred Hummingbirds at Two Cents Each |

||

|

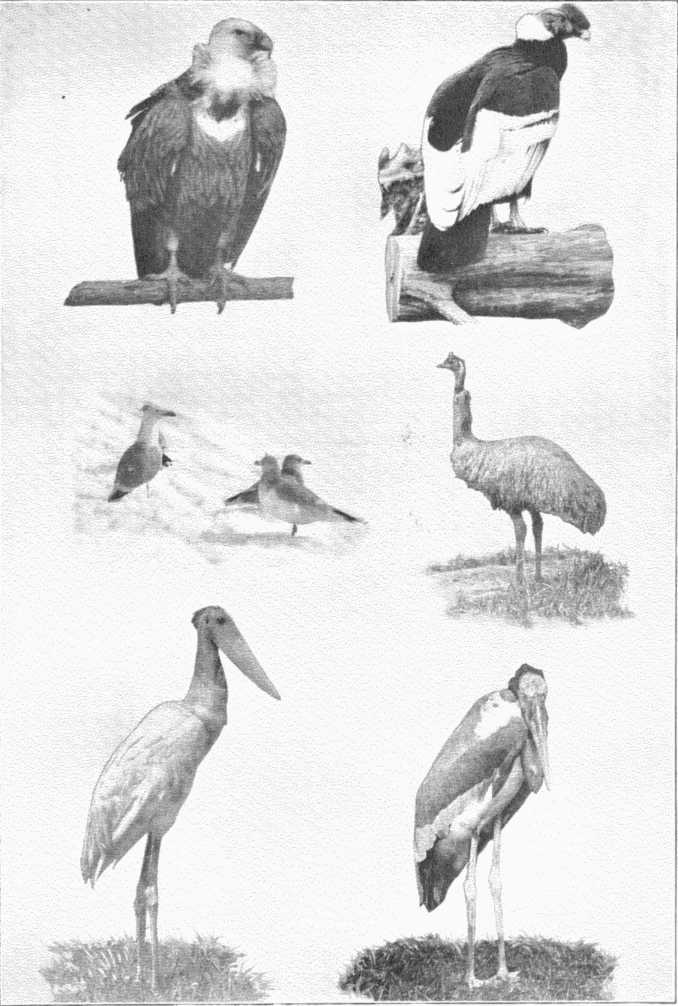

Beautiful and Curious Birds Destroyed for the Feather Trade—II |

||

|

Beautiful and Curious Birds—III |

||

|

Fight in England Against the Use of Plumage |

[Page†xv] | |

|

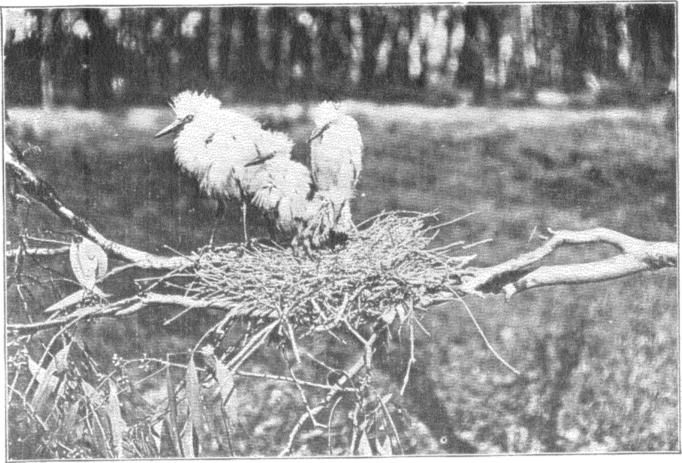

Young Egrets, Unable to Fly, Starving |

||

|

Snowy Egret Dead on Her Nest |

||

|

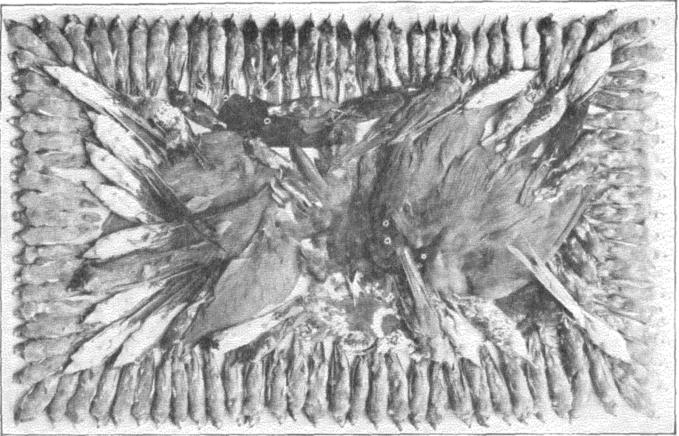

Miscellaneous Bird Skins, Eight Cents Each |

||

|

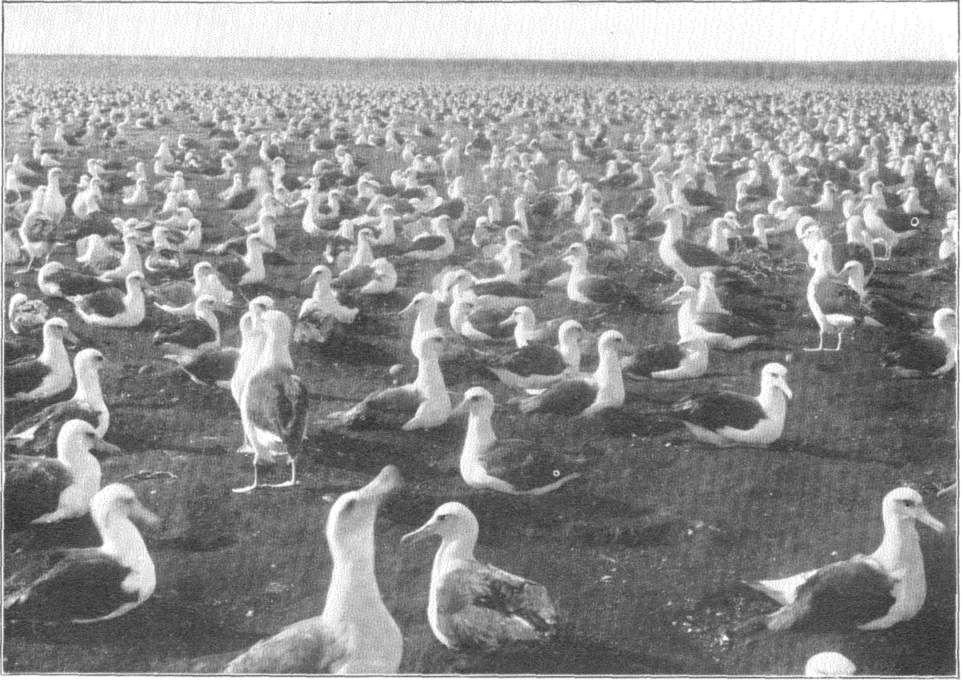

Laysan Albatrosses, Before the Great Slaughter |

||

|

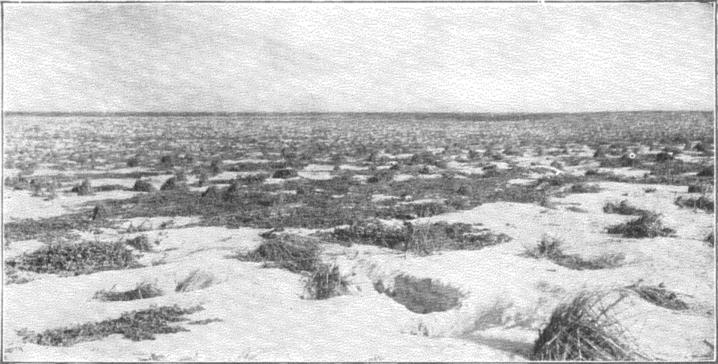

Laysan Albatross Rookery, After the Great Slaughter |

||

|

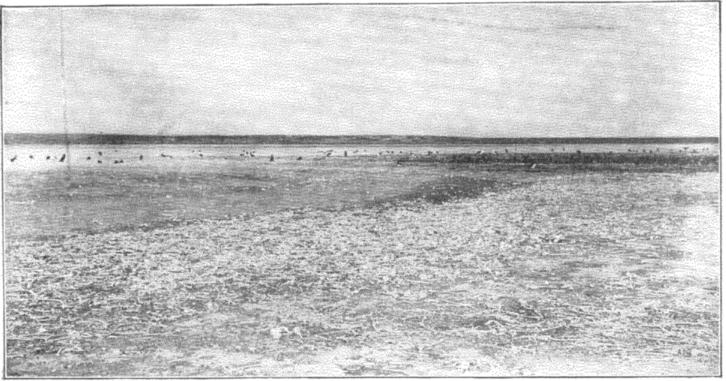

Acres of Gull and Albatross Bones |

||

|

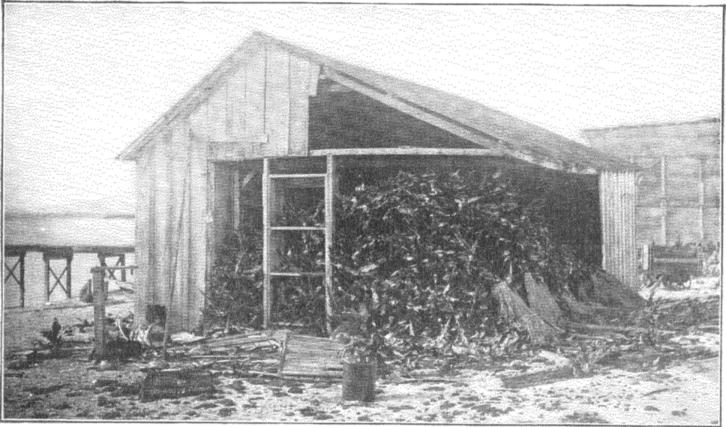

Shed Filled with Wings of Slaughtered Birds |

||

|

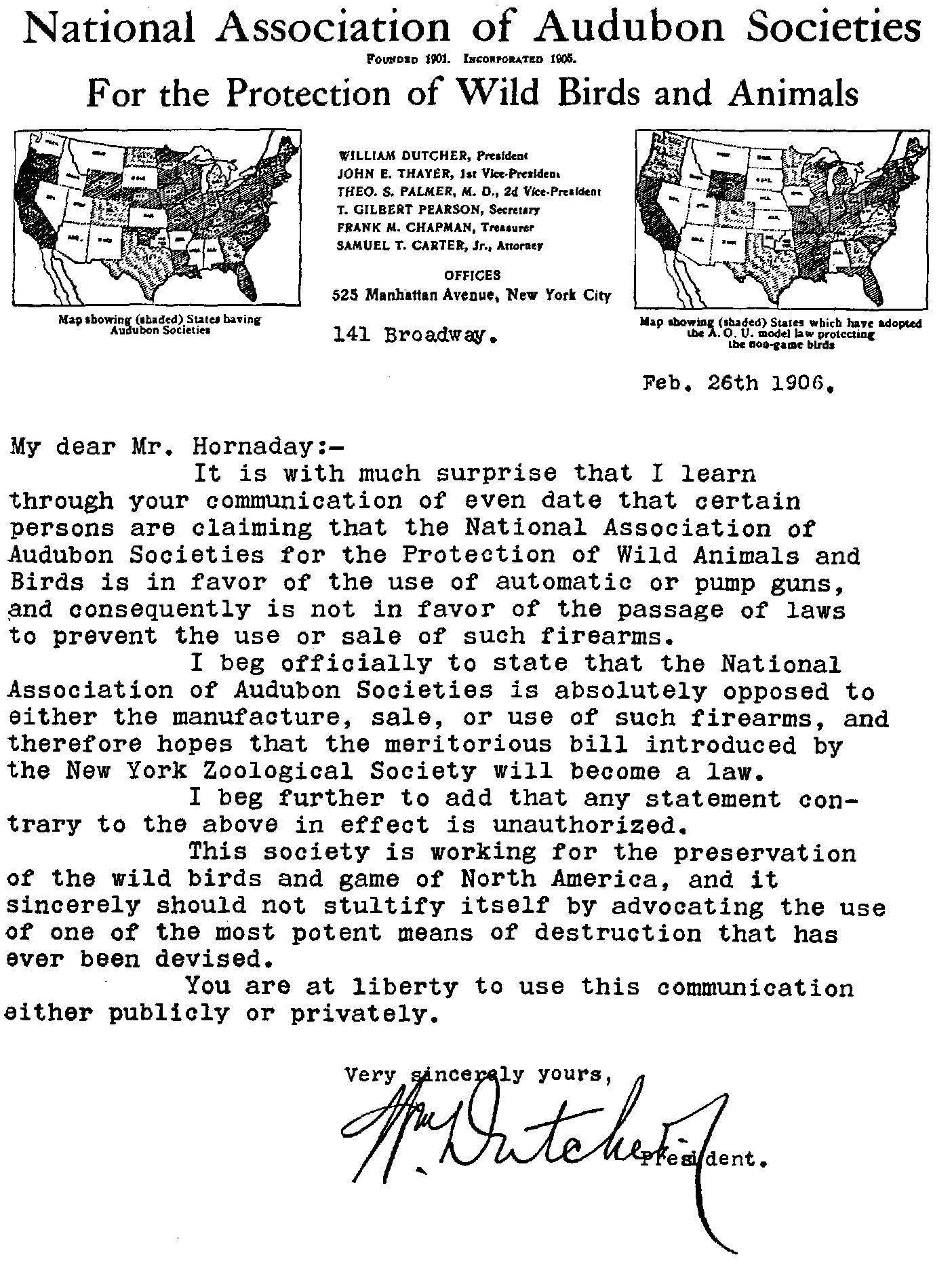

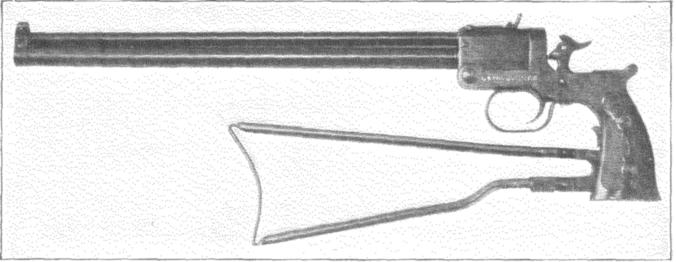

Four of the Seven Machine Guns |

||

|

The Champion Game-Slaughter Case |

||

|

Slaughtered According to Law |

||

|

A Letter that Tells its Own Story |

||

|

The "Sunday Gun" |

||

|

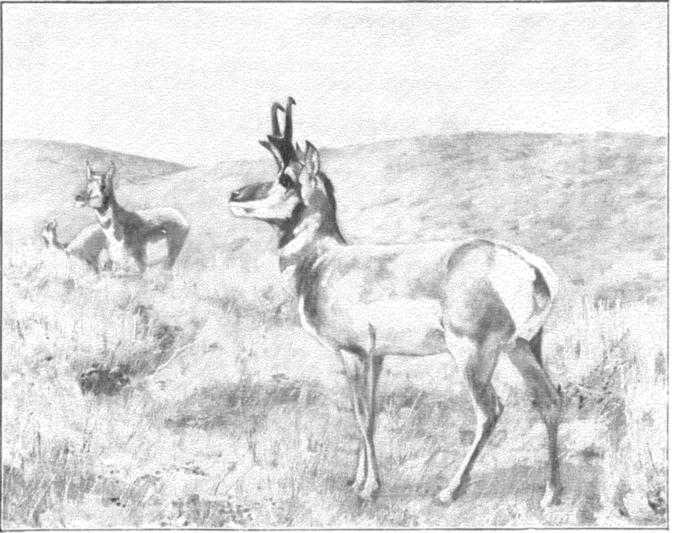

The Prong-Horned Antelope |

||

|

Hungry Elk in Jackson Hole |

||

|

The Wichita National Bison Herd |

||

|

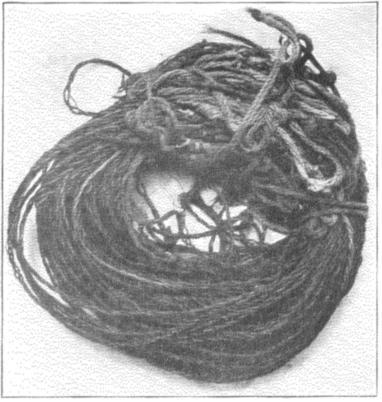

Pheasant Snares |

||

|

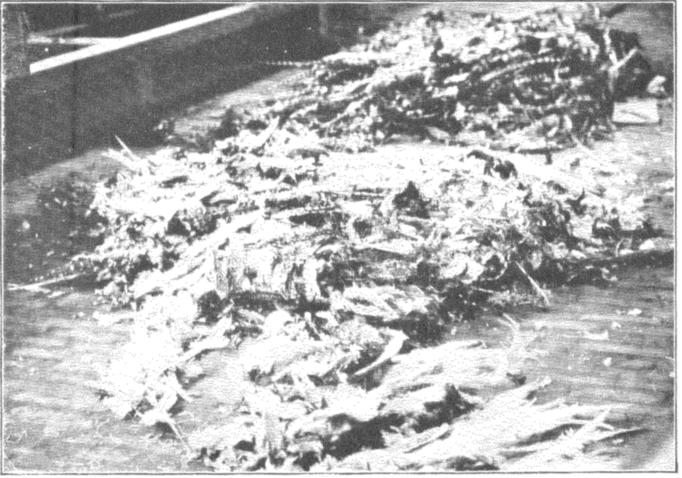

Pheasant Skins Seized at Rangoon |

||

|

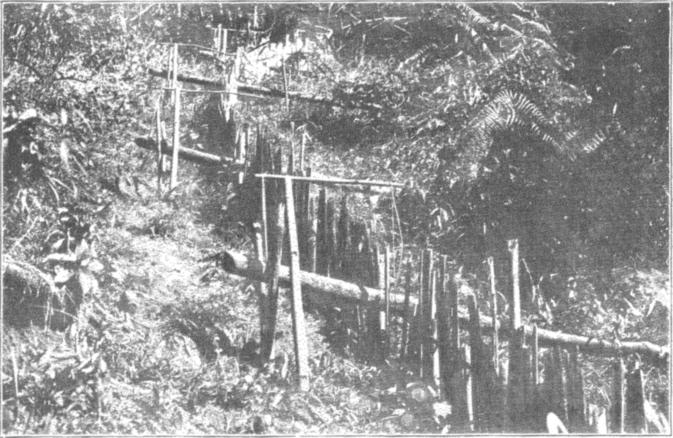

Deadfall Traps in Burma |

||

|

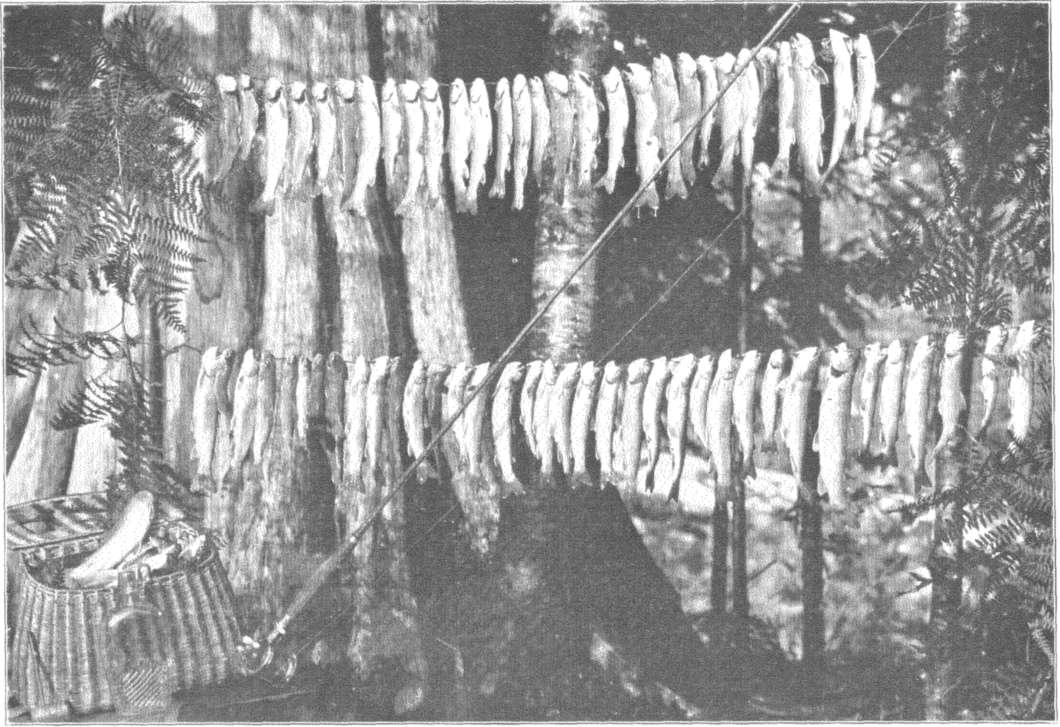

One Morning's Catch of Trout near Spokane |

||

|

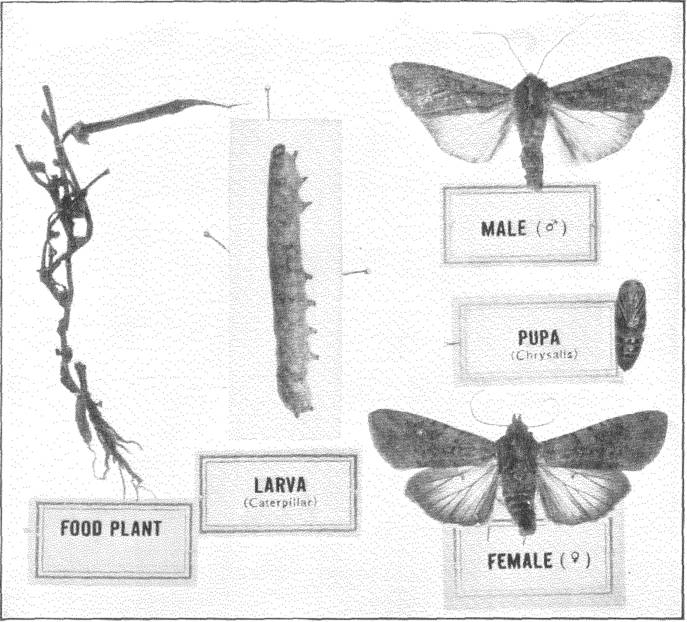

The Cut-Worm |

||

|

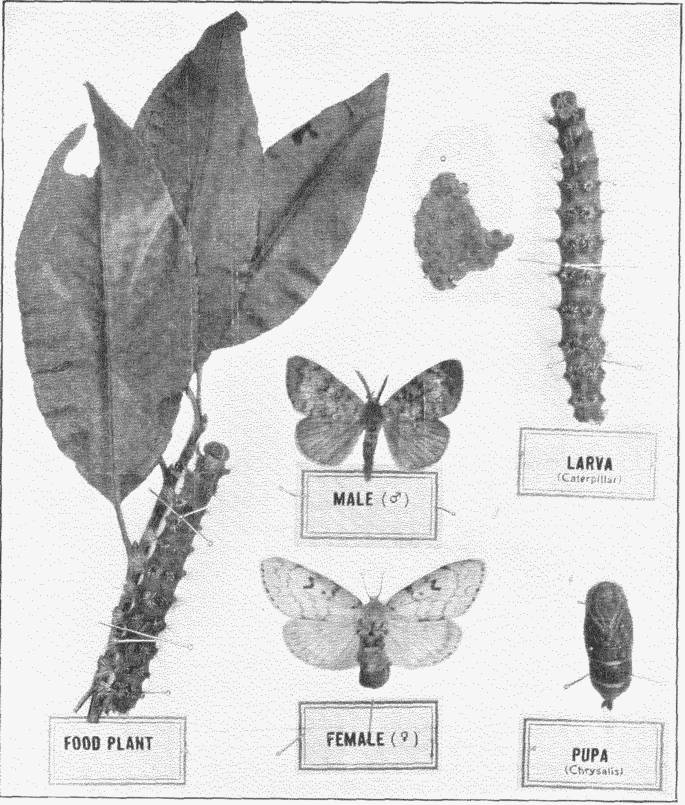

The Gypsy Moth |

||

|

Downy Woodpecker |

||

|

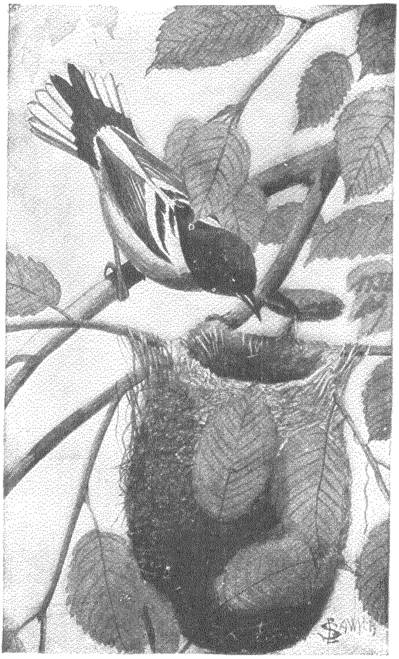

Baltimore Oriole |

||

|

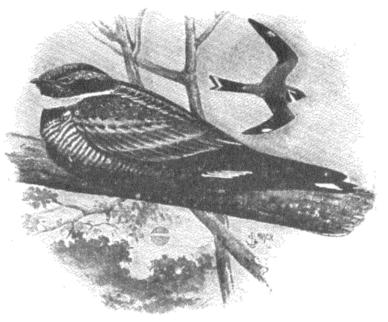

Nighthawk |

||

|

Purple Martin |

||

|

Bob-White |

||

|

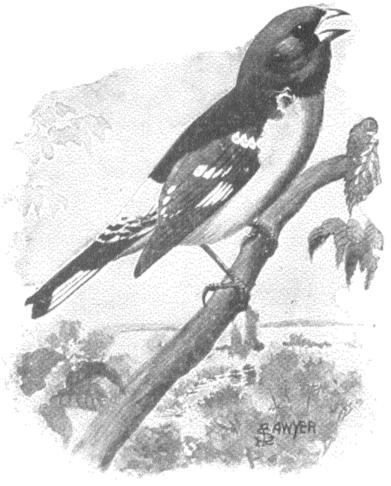

Rose-Breasted Grosbeak |

||

|

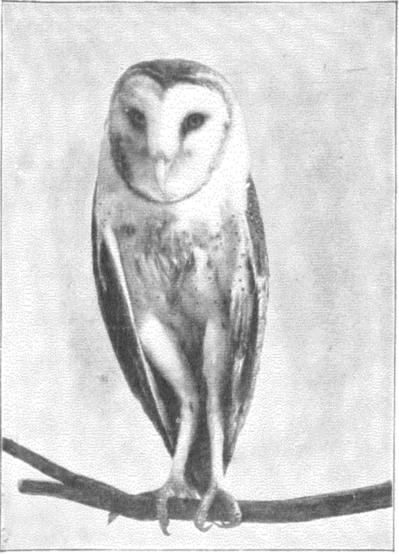

Barn Owl |

||

|

Golden-Winged Woodpecker |

||

|

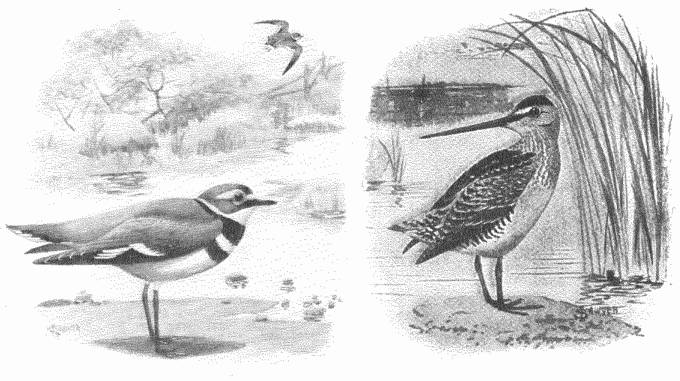

Kildeer Plover |

||

|

Jacksnipe |

||

|

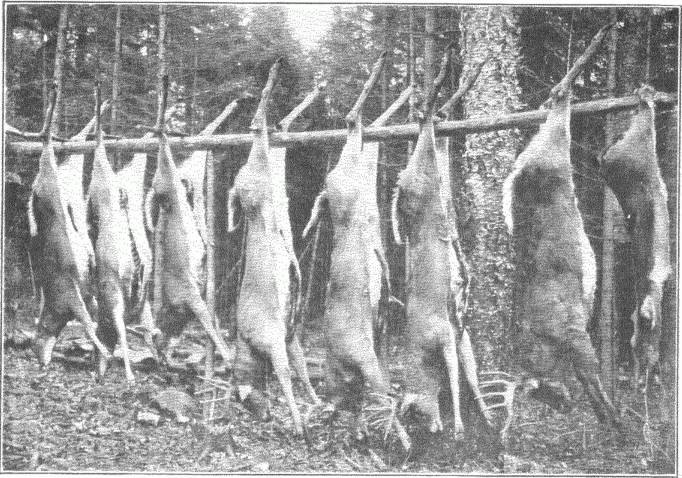

A Food Supply of White-Tailed Deer |

||

|

White-Tailed Deer |

||

|

Notable Protectors of Wild Life: Madison Grant, Henry Fairfield Osborn, John F. Lacey, and William Dutcher |

||

|

Notable Protectors: Forbush, Pearson, Burnham, Napier |

||

|

Notable Protectors: Phillips, Kalbfus, McIlhenny, Ward |

||

|

Band-Tailed Pigeon |

||

|

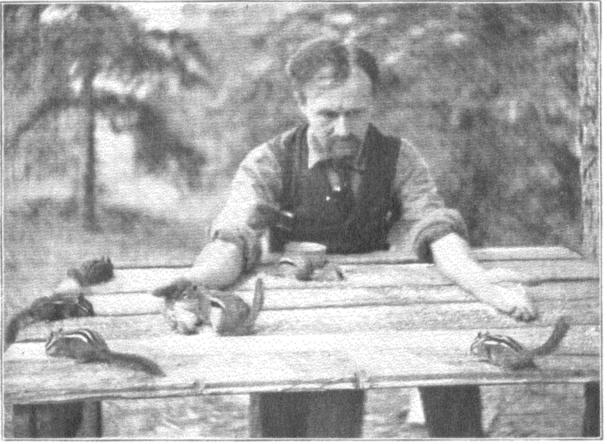

Six Wild Chipmunks Dine with Mr. Loring |

||

|

Chickadee, Tamed |

||

|

Chipmunk, Tamed |

||

|

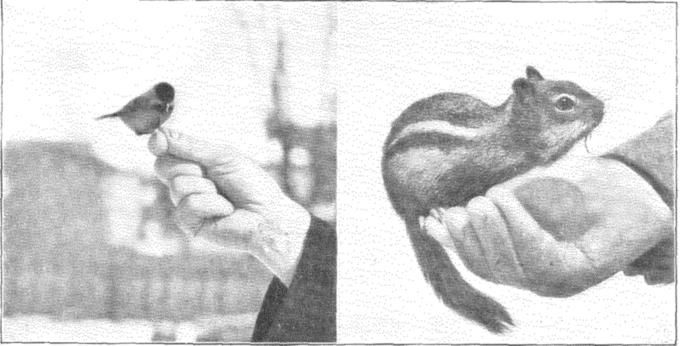

Object Lesson in Bringing Back the Ducks |

||

|

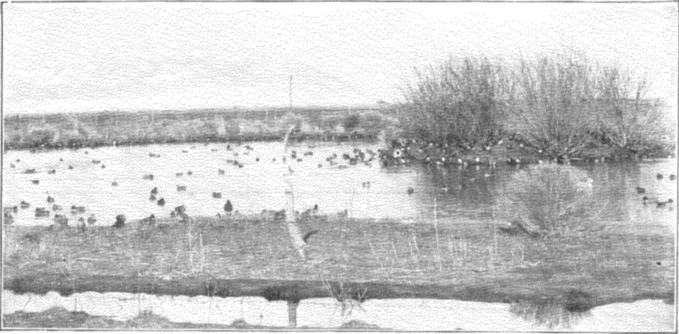

Gulls and Terns of Our Coast |

||

|

Egrets and Herons in Sanctuary on Marsh Island |

||

|

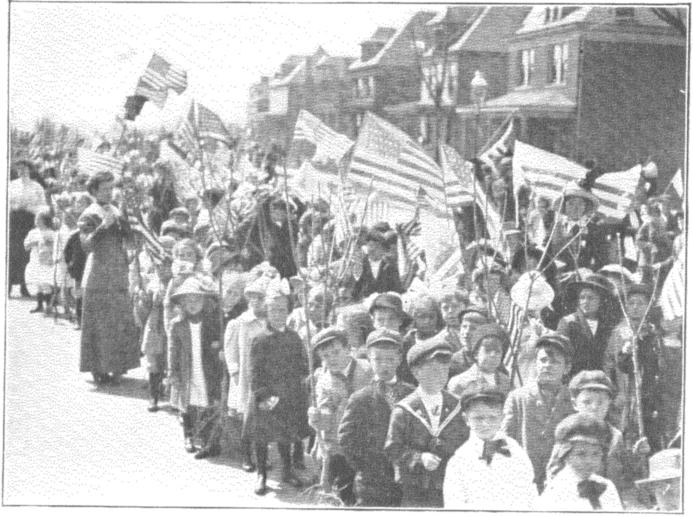

Bird Day at Carrick, Pa |

||

|

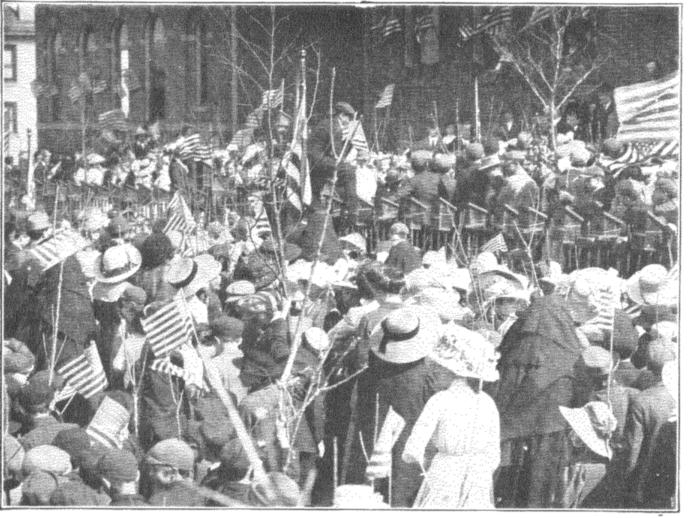

Distributing Bird Boxes and Fruit Trees |

[Page†xvi] | |

|

MAPS |

||

|

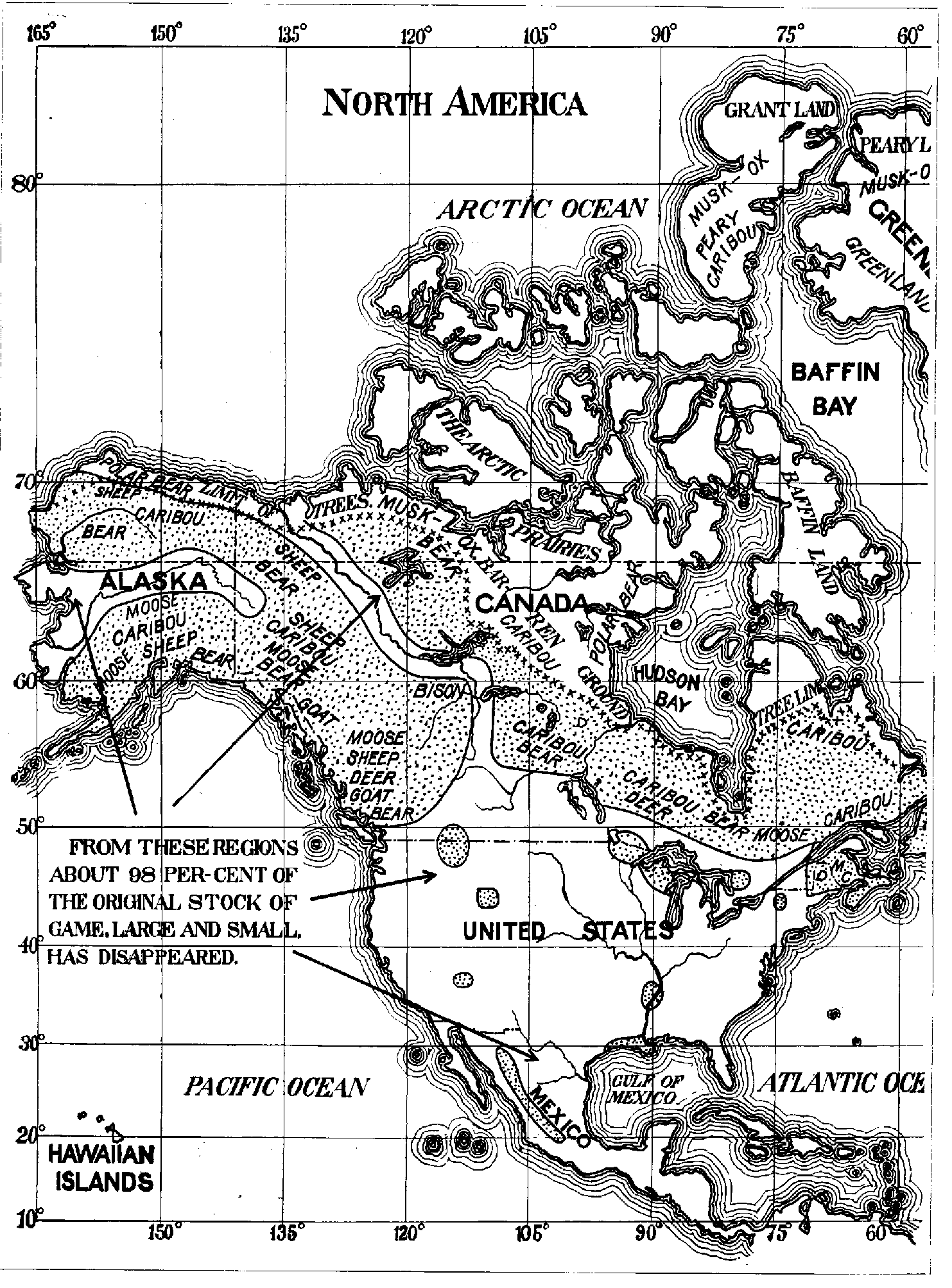

The Wilderness of North America |

||

|

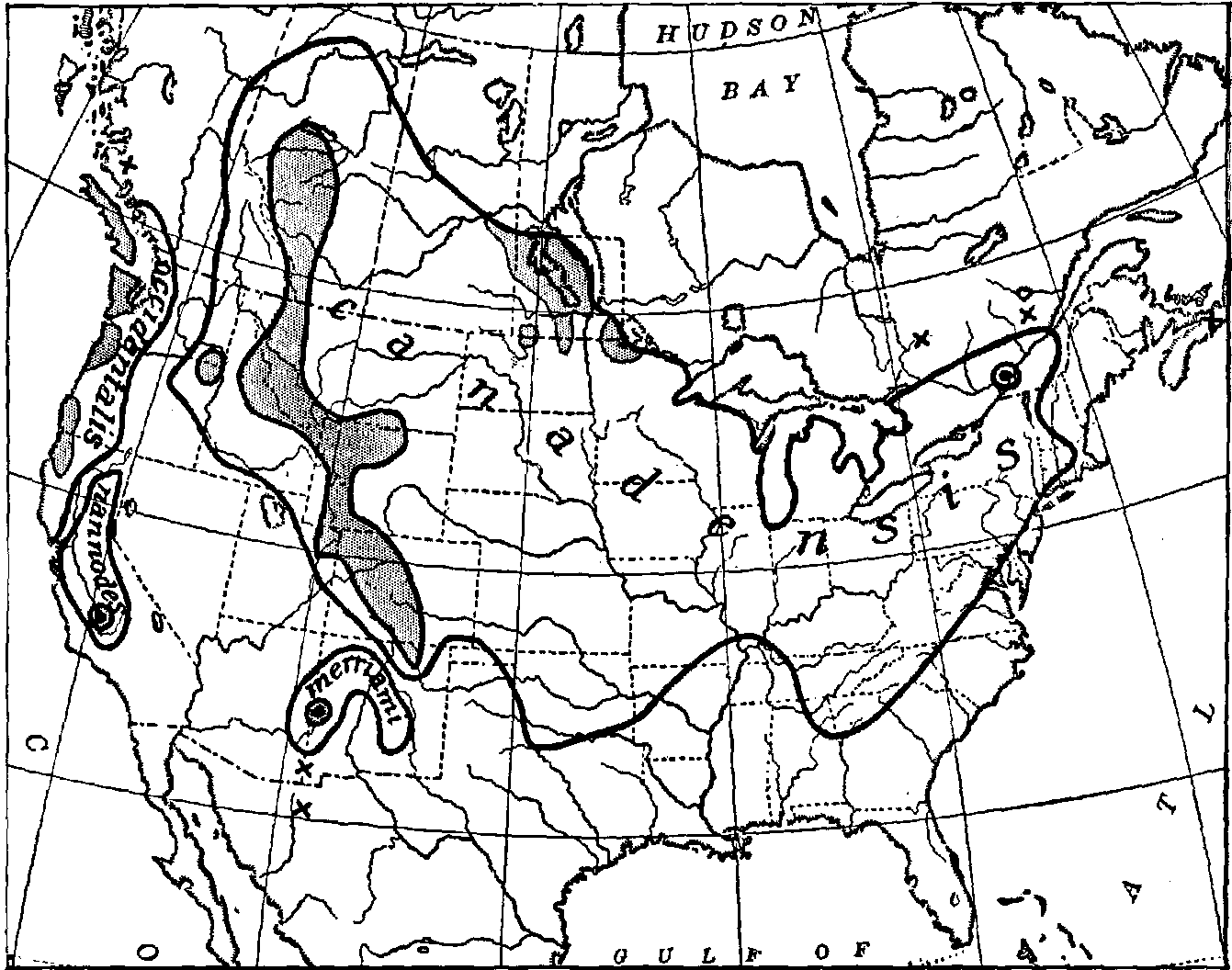

Former and Existing Ranges of the Elk |

||

|

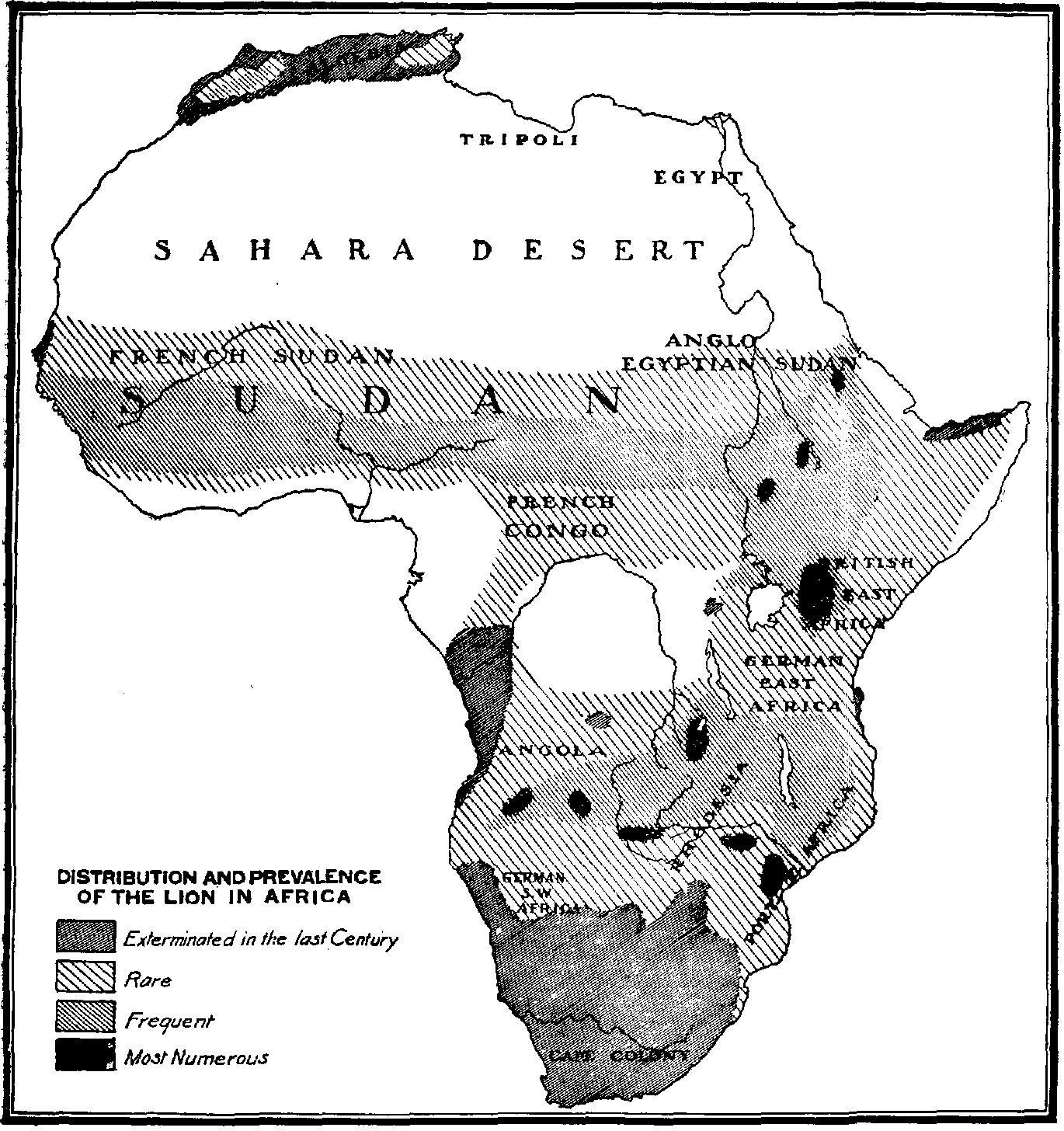

Map Showing the Disappearance of the Lion |

||

|

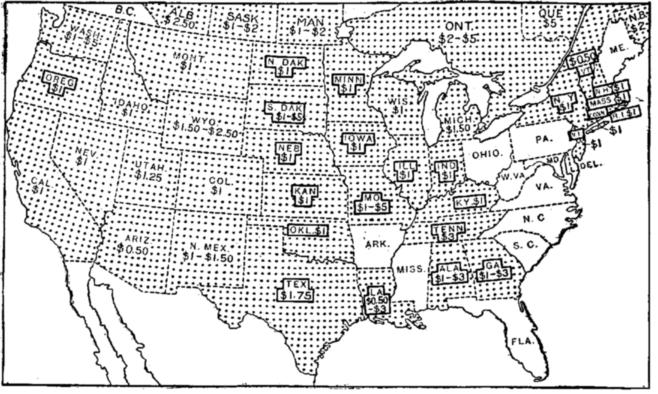

States and Provinces Requiring Resident Licenses. |

||

|

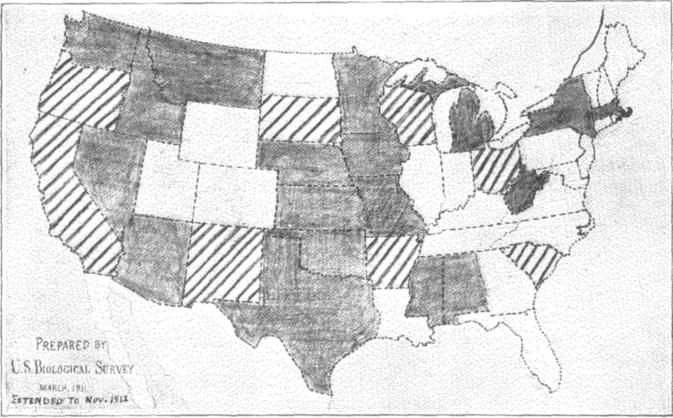

Eighteen States Prohibit the Sale of Game |

||

|

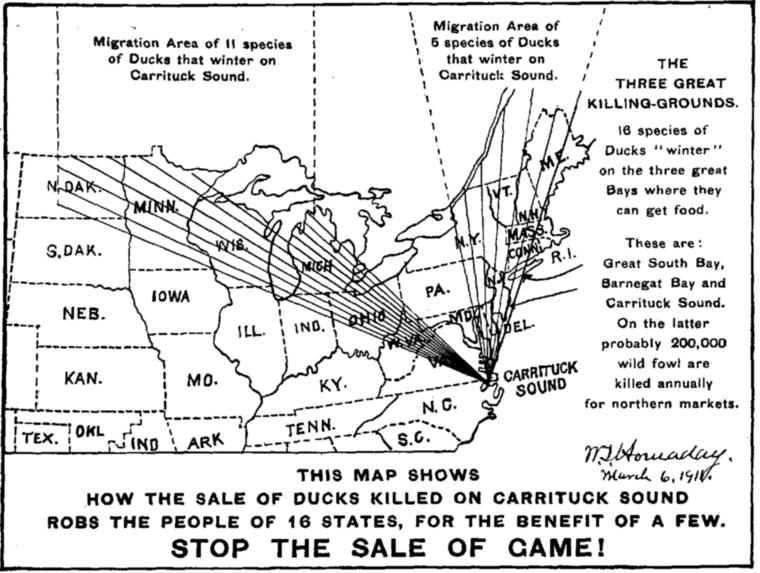

Map Used in Campaign for Bayne Law |

||

|

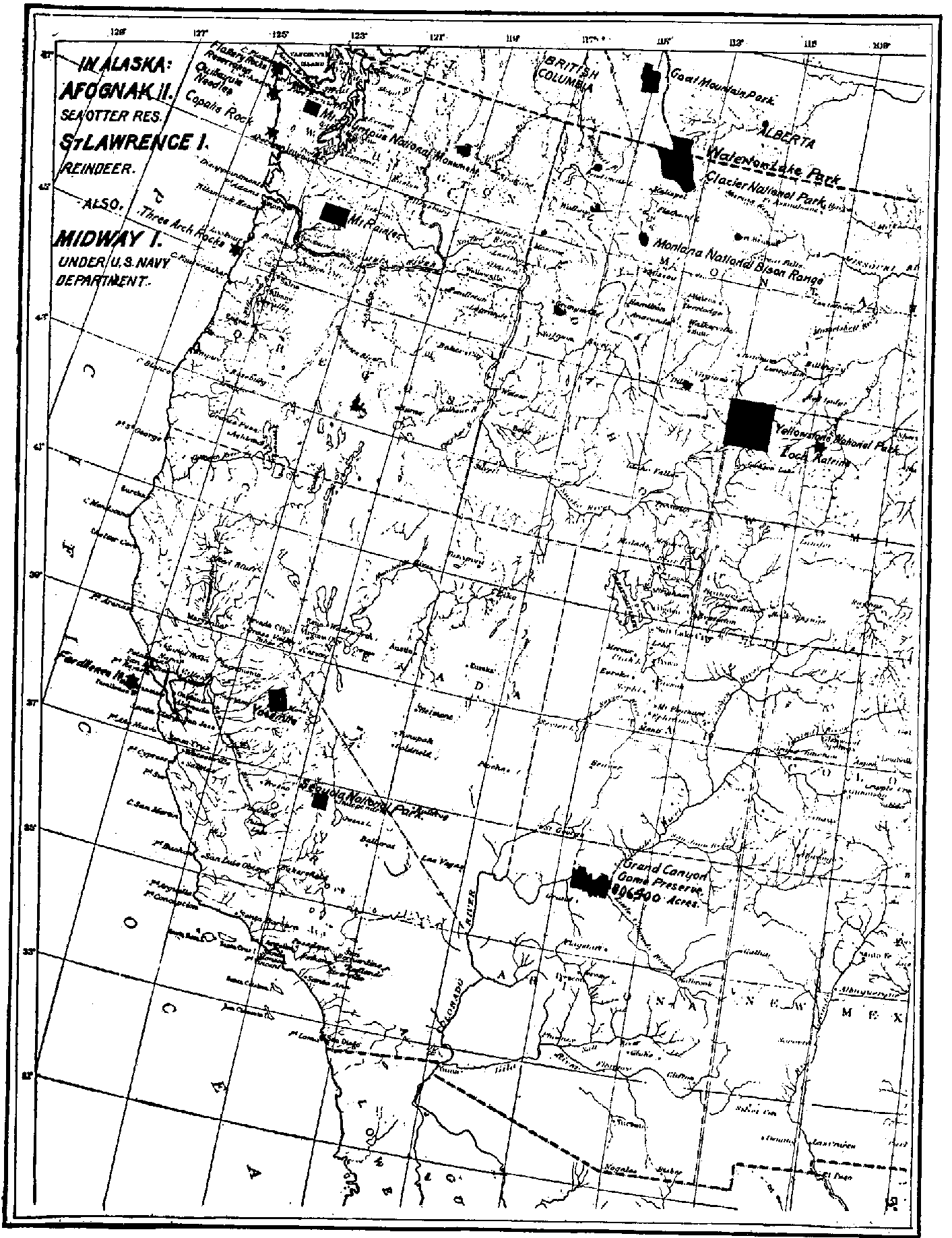

United States National Game Preserves |

||

|

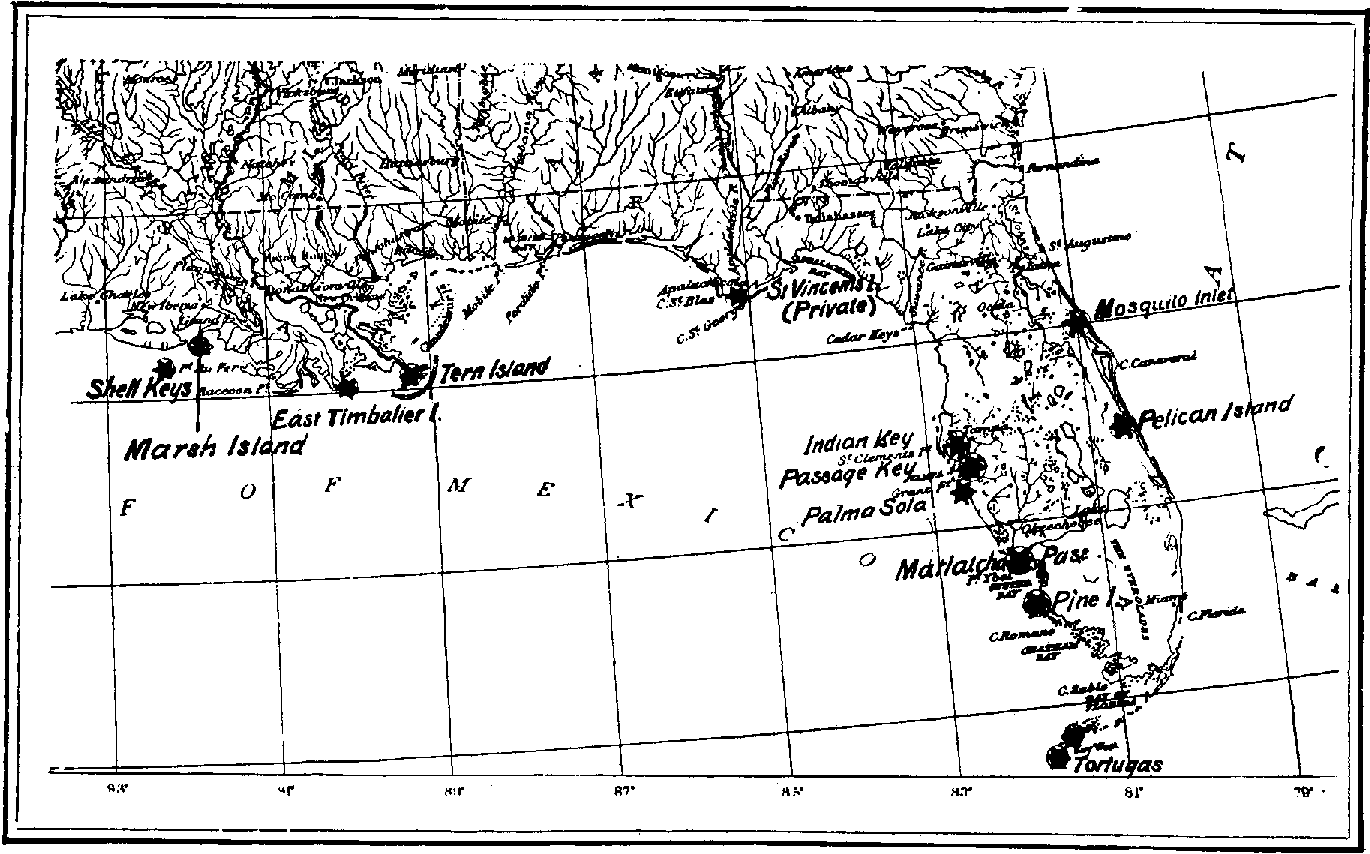

Bird Reservations on the Gulf Coast and Florida |

||

|

Marsh Island and Adjacent Preserves |

||

|

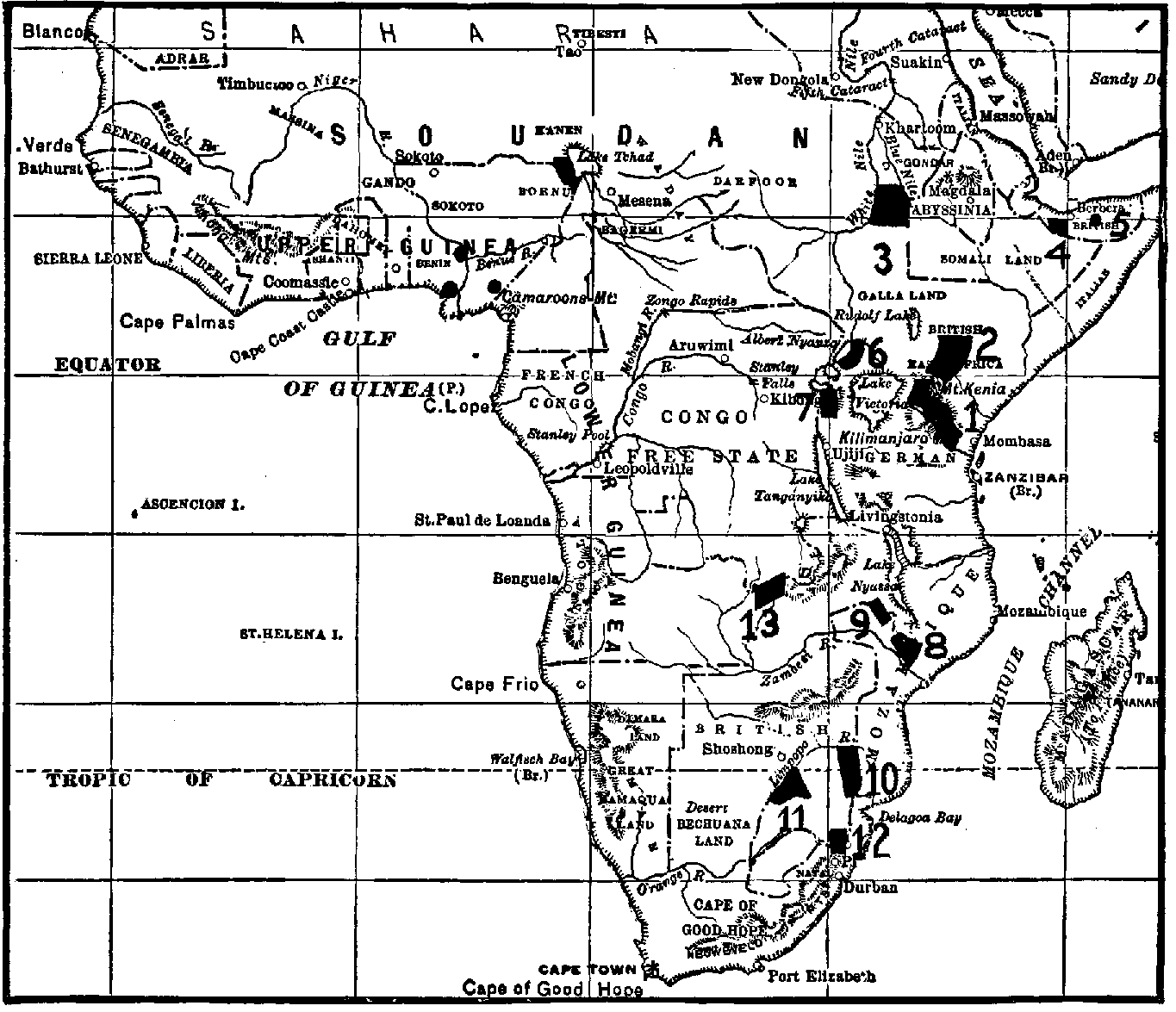

Most Important Game Preserves of Africa |

||

"By my labors my vineyard flourished. But Ahab came. Alas! for Naboth."

In order that the American people may correctly understand and judge the question of the extinction or preservation of our wild life, it is necessary to recall the near past. It is not necessary, however, to go far into the details of history; for a few quick glances at a few high points will be quite sufficient for the purpose in view.

Any man who reads the books which best tell the story of the development of the American colonies of 1712 into the American nation of 1912, and takes due note of the wild-life features of the tale, will say without hesitation that when the American people received this land from the bountiful hand of Nature, it was endowed with a magnificent and all-pervading supply of valuable wild creatures. The pioneers and the early settlers were too busy even to take due note of that fact, or to comment upon it, save in very fragmentary ways.

Nevertheless, the wild-life abundance of early American days survived down to so late a period that it touched the lives of millions of people now living. Any man 55 years of age who when a boy had a taste for "hunting,"—for at that time there were no "sportsmen" in America,—will remember the flocks and herds of wild creatures that he saw and which made upon his mind many indelible impressions.

"Abundance" is the word with which to describe the original animal life that stocked our country, and all North America, only a short half-century ago. Throughout every state, on every shore-line, in all the millions of fresh water lakes, ponds and rivers, on every mountain range, in every forest, and even on every desert, the wild flocks and herds held sway. It was impossible to go beyond the settled haunts of civilized man and escape them.

It was a full century after the complete settlement of New England and the Virginia colonies that the wonderful big-game fauna of the great plains and Rocky Mountains was really discovered; but the bison [Page†2] millions, the antelope millions, the mule deer, the mountain sheep and mountain goat were there, all the time. In the early days, the millions of pinnated grouse and quail of the central states attracted no serious attention from the American people-at-large; but they lived and flourished just the same, far down in the seventies, when the greedy market gunners systematically slaughtered them, and barreled them up for "the market," while the foolish farmers calmly permitted them to do it.

We obtain the best of our history of the former abundance of North American wild life first from the pages of Audubon and Wilson; next, from the records left by such pioneers as Lewis and Clark, and last from the testimony of living men. To all this we can, many of us, add observations of our own.

To me the most striking fact that stands forth in the story of American wild life one hundred years ago is the wide extent and thoroughness of its distribution. Wide as our country is, and marvelous as it is in the diversity of its climates, its soils, its topography, its flora, its riches and its poverty, Nature gave to each square mile and to each acre a generous quota of wild creatures, according to its ability to maintain living things. No pioneer ever pushed so far, or into regions so difficult or so remote, that he did not find awaiting him a host of birds and beasts. Sometimes the pioneer was not a good hunter; usually he was a stupid fisherman; but the "game" was there, nevertheless. The time was when every farm had its quota.

The part that the wild life of America played in the settlement and development of this continent was so far-reaching in extent, and so enormous in potential value, that it fairly staggers the imagination. From the landing of the Pilgrims down to the present hour the wild game has been the mainstay and the resource against starvation of the pathfinder, the settler, the prospector, and at times even the railroad-builder. In view of what the bison millions did for the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Kansas and Texas, it is only right and square that those states should now do something for the perpetual preservation of the bison species and all other big game that needs help.

For years and years, the antelope millions of the Montana and Wyoming grass-lands fed the scout and Indian-fighter, freighter, cowboy and surveyor, ranchman and sheep-herder; but thus far I have yet to hear of one Western state that has ever spent one penny directly for the preservation of the antelope! And to-day we are in a hand-to-hand fight in Congress, and in Montana, with the Wool-Growers Association, which maintains in Washington a keen lobbyist to keep aloft the tariff on wool, and prevent Congress from taking 15 square miles of grass lands on Snow Creek, Montana, for a National Antelope Preserve. All that the wool-growers want is the entire earth, all to themselves. Mr. McClure, the Secretary of the Association says:

"The proper place in which to preserve the big game of the West is in city parks, where it can be protected."

[Page†3]To the colonist of the East and pioneer of the West, the white-tailed deer was an ever present help in time of trouble. Without this omnipresent animal, and the supply of good meat that each white flag represented, the commissariat difficulties of the settlers who won the country as far westward as Indiana would have been many times greater than they were. The backwoods Pilgrim's progress was like this:

Trail, deer; cabin, deer; clearing; bear, corn, deer; hogs, deer; cattle, wheat, independence.

And yet, how many men are there to-day, out of our ninety millions of Americans and pseudo-Americans, who remember with any feeling of gratitude the part played in American history by the white-tailed deer? Very few! How many Americans are there in our land who now preserve that deer for sentimental reasons, and because his forbears were nation-builders? As a matter of fact, are there any?

On every eastern pioneer's monument, the white-tailed deer should figure; and on those of the Great West, the bison and the antelope should be cast in enduring bronze, "lest we forget!"

The game birds of America played a different part from that of the deer, antelope and bison. In the early days, shotguns were few, and shot was scarce and dear. The wild turkey and goose were the smallest birds on which a rifleman could afford to expend a bullet and a whole charge of powder. It was for this reason that the deer, bear, bison, and elk disappeared from the eastern United States while the game birds yet remained abundant. With the disappearance of the big game came the fat steer, hog and hominy, the wheat-field, fruit orchard and poultry galore.

The game birds of America, as a class and a mass, have not been swept away to ward off starvation or to rescue the perishing. Even back in the sixties and seventies, very, very few men of the North thought of killing prairie chickens, ducks and quail, snipe and woodcock, in order to keep the hunger wolf from the door. The process was too slow and uncertain; and besides, the really-poor man rarely had the gun and ammunition. Instead of attempting to live on birds, he hustled for the staple food products that the soil of his own farm could produce.

First, last and nearly all the time, the game birds of the United States as a whole, have been sacrificed on the altar of Rank Luxury, to tempt appetites that were tired of fried chicken and other farm delicacies. To-day, even the average poor man hunts birds for the joy of the outing, and the pampered epicures of the hotels and restaurants buy game birds, and eat small portions of them, solely to tempt jaded appetites. If there is such a thing as "class" legislation, it is that which permits a few sordid market-shooters to slaughter the birds of the whole people in order to sell them to a few epicures.

The game of a state belongs to the whole people of the state. The Supreme Court of the United States has so decided. (Geer vs. Connecticut). If it is abundant, it is a valuable asset. The great value of the game birds of America lies not in their meat pounds as they lie upon [Page†4] the table, but in the temptation they annually put before millions of field-weary farmers and desk-weary clerks and merchants to get into their beloved hunting togs, stalk out into the lap of Nature, and say "Begone, dull Care!"

And the man who has had a fine day in the painted woods, on the bright waters of a duck-haunted bay, or in the golden stubble of September, can fill his day and his soul with six good birds just as well as with sixty. The idea that in order to enjoy a fine day in the open a man must kill a wheel-barrow load of birds, is a mistaken idea; and if obstinately adhered to, it becomes vicious! The Outing in the Open is the thing,—not the blood-stained feathers, nasty viscera and Death in the game-bag. One quail on a fence is worth more to the world than ten in a bag.

The farmers of America have, by their own supineness and lack of foresight, permitted the slaughter of a stock of game birds which, had it been properly and wisely conserved, would have furnished a good annual shoot to every farming man and boy of sporting instincts through the past, right down to the present, and far beyond. They have allowed millions of dollars worth of their birds to be coolly snatched away from them by the greedy market-shooters.

There is one state in America, and so far as I know only one, in which there is at this moment an old-time abundance of game-bird life. That is the state of Louisiana. The reason is not so very far to seek. For the birds that do not migrate,—quail, wild turkeys and doves,—the cover is yet abundant. For the migratory game birds of the Mississippi Valley, Louisiana is a grand central depot, with terminal facilities that are unsurpassed. Her reedy shores, her vast marshes, her long coast line and abundance of food furnish what should be not only a haven but a heaven for ducks and geese. After running the gauntlet of guns all the way from Manitoba and Ontario to the Sunk Lands of Arkansas, the shores of the Gulf must seem like heaven itself.

The great forests of Louisiana shelter deer, turkeys, and fur-bearing animals galore; and rabbits and squirrels abound.

Naturally, this abundance of game has given rise to an extensive industry in shooting for the market. The "big interests" outside the state send their agents into the best game districts, often bringing in their own force of shooters. They comb out the game in enormous quantities, without leaving to the people of Louisiana any decent and fair quid-pro-quo for having despoiled them of their game and shipped a vast annual product outside, to create wealth elsewhere.

At present, however, we are but incidentally interested in the short-sightedness of the people of the Pelican State. As a state of oldtime abundance in killable game, the killing records that were kept in the year 1909-10 possess for us very great interest. They throw a startling searchlight on the subject of this chapter,—the former abundance of wild life.

From the records that with great pains and labor were gathered by the State Game Commission, and which were furnished me for use here by [Page†5] President Frank M. Miller, we set forth this remarkable exhibit of old-fashioned abundance in game, A.D. 1909.

| Official Record Of Game Killed In Louisiana During The Season (12 Months) Of 1909-10 | |

|---|---|

| Birds | |

| Wild Ducks, sea and river | 3,176,000 |

| Coots | 280,740 |

| Geese and Brant | 202,210 |

| Snipe, Sandpiper and Plover | 606,635 |

| Quail (Bob-White) | 1,140,750 |

| Doves | 310,660 |

| Wild Turkeys | 2,219 |

| --------- | |

| ††††Total number of game birds killed | 5,719,214 |

| Mammals | |

| Deer | 5,470 |

| Squirrels and Rabbits | 690,270 |

| --------- | |

| ††††Total of game mammals | 695,740 |

| Fur-bearing mammals | 1,971,922 |

| --------- | |

| ††††Total of mammals | 2,667,662 |

| --------- | |

| ††††Grand total of birds and mammals | 8,386,876 |

Of the thousands of slaughtered robins, it would seem that no records exist. It is to be understood that the annual slaughter of wild life in Louisiana never before reached such a pitch as now. Without drastic measures, what will be the inevitable result? Does any man suppose that even the wild millions of Louisiana can long withstand such slaughter as that shown by the official figures given above? It is wildly impossible.

But the darkest hour is just before the dawn. At the session of the Louisiana legislature that was held in the spring of 1912, great improvements were made in the game laws of that state. The most important feature was the suppression of wholesale market hunting, by persons who are not residents of the state. A very limited amount of game may be sold and served as food in public places, but the restrictions placed upon this traffic are so effective that they will vastly reduce the annual slaughter. In other respects, also, the cause of wild life protection gained much; for which great credit is due to Mr. Edward A. McIlhenny.

It is the way of Americans to feel that because game is abundant in a given place at a given time, it always will be abundant, and may therefore be slaughtered without limit. That was the case last winter in California during the awful slaughter of band-tailed pigeons, as will be noted elsewhere.

It is time for all men to be told in the plainest terms that there never has existed, anywhere in historic times, a volume of wild life so great that civilized man could not quickly exterminate it by his methods of [Page†6] destruction. Lift the veil and look at the stories of the bison, the passenger pigeon, the wild ducks and shore birds of the Atlantic coast, and the fur-seal.

SHALL WE LEAVE ANY ONE OF THEM OPEN?

As reasoning beings, it is our duty to heed the lessons of history, and not rush blindly on until we perpetrate a continent destitute of wild life.

For educated, civilized Man to exterminate a valuable wild species of living things is a crime. It is a crime against his own children, and posterity.

No man has a right, either moral or legal, to destroy or squander an inheritance of his children that he holds for them in trust. And man, the wasteful and greedy spendthrift that he is, has not created even the humblest of the species of birds, mammals and fishes that adorn and enrich this earth. "The earth is THE LORD'S, and the fulness thereof!" With all his wisdom, man has not evolved and placed here so much as a ground-squirrel, a sparrow or a clam. It is true that he has juggled with the wild horse and sheep, the goats and the swine, and produced some hardy breeds that can withstand his abuse without going down before it; but as for species, he has not yet created and placed here even so much as a protozoan.

The wild things of this earth are not ours, to do with as we please. They have been given to us in trust, and we must account for them to the generations which will come after us and audit our accounts.

But man, the shameless destroyer of Nature's gifts, blithely and persistently exterminates one species after another. Fully ten per cent of the human race consists of people who will lie, steal, throw rubbish in parks, and destroy forests and wild life whenever and wherever they can do so without being stopped by a policemen and a club. These are hard words, but they are absolutely true. From ten per cent (or more) of the human race, the high moral instinct which is honest without compulsion is absent. The things that seemingly decent citizens,—men posing as gentlemen,—will do to wild game when they secure great chances to slaughter, are appalling. I could fill a book of this size with cases in point.

To-day the women of England, Europe and elsewhere are directly promoting the extermination of scores of beautiful species of wild birds by the devilish persistence with which they buy and wear feather ornaments made of their plumage. They are just as mean and cruel as the truck-driver who drives a horse with a sore shoulder and beats him on the street. But they do it! And appeals to them to do otherwise they laugh to scorn, saying, "I will wear what is fashionable, when I please and where I please!" As a famous bird protector of England has just written me, "The women of the smart set are beyond the reach of appeal or protest."

[Page†8]To-day, the thing that stares me in the face every waking hour, like a grisly spectre with bloody fang and claw, is the extermination of species. To me, that is a horrible thing. It is wholesale murder, no less. It is capital crime, and a black disgrace to the races of civilized mankind. I say "civilized mankind," because savages don't do it!

There are three kinds of extermination:

The practical extermination of a species means the destruction of its members to an extent so thorough and widespread that the species disappears from view, and living specimens of it can not be found by seeking for them. In North America this is to-day the status of the whooping crane, upland plover, and several other species. If any individuals are living, they will be met with only by accident.

The absolute extermination of a species means that not one individual of it remains alive. Judgment to this effect is based upon the lapse of time since the last living specimen was observed or killed. When five years have passed without a living "record" of a wild specimen, it is time to place a species in the class of the totally extinct.

Extermination in a wild state means that the only living representatives are in captivity or otherwise under protection. This is the case of the heath hen and David's deer, of China. The American bison is saved from being wholly extinct as a wild animal by the remnant of about 300 head in northern Athabasca, and 49 head in the Yellow-stone Park.

It is a serious thing to exterminate a species of any of the vertebrate animals. There are probably millions of people who do not realize that civilized (!) man is the most persistently and wickedly wasteful of all the predatory animals. The lions, the tigers, the bears, the eagles and hawks, serpents, and the fish-eating fishes, all live by destroying life; but they kill only what they think they can consume. If something is by chance left over, it goes to satisfy the hunger of the humbler creatures of prey. In a state of nature, where wild creatures prey upon wild creatures, such a thing as wanton, wholesale and utterly wasteful slaughter is almost unknown!

When the wild mink, weasel and skunk suddenly finds himself in the midst of scores of man's confined and helpless domestic fowls, or his caged gulls in a zoological park, an unusual criminal passion to murder for the joy of killing sometimes seizes the wild animal, and great slaughter is the result.

From the earliest historic times, it has been the way of savage man, red, black, brown and yellow, to kill as the wild animals do,—only what he can use, or thinks he can use. The Cree Indian impounded small herds of bison, and sometimes killed from 100 to 200 at one time; but it was to make sure of having enough meat and hides, and because he expected to use the product. I think that even the worst enemies of the plains Indians hardly will accuse them of killing large numbers of bison, elk or deer merely for the pleasure of seeing them fall, or taking only their teeth.

[Page†9]

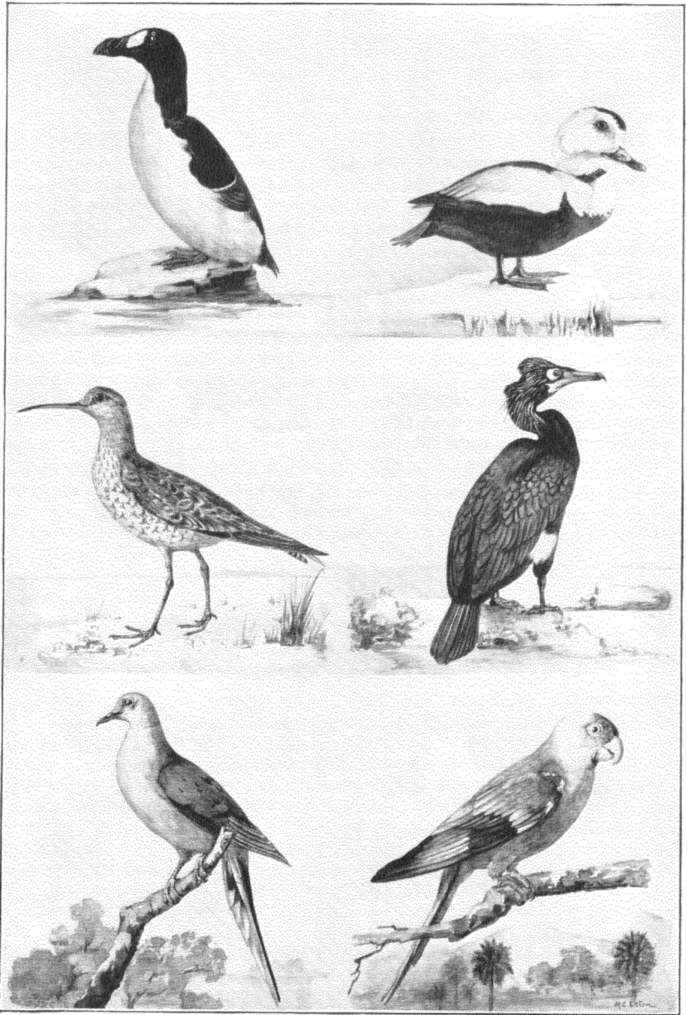

| SIX RECENTLY EXTERMINATED NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS: | |||

| Great Auk | Labrador Duck | ||

| Eskimo Curlew | Pallas Cormorant | ||

| Passenger Pigeon | Carolina Parrakee | ||

It has remained for the wolf, the sheep-killing dog and civilized man to make records of wanton slaughter which puts them in a class together, [Page†10] and quite apart from other predatory animals. When a man can kill bison for their tongues alone, bull elk for their "tusks" alone, and shoot a whole colony of hippopotami,—actually damming a river with their bloated and putrid carcasses, all untouched by the knife,—the men who do such things must be classed with the cruel wolf and the criminal dog.

It is now desirable that we should pause in our career of destruction long enough to look back upon what we have recently accomplished in the total extinction of species, and also note what we have blocked out for the immediate future. Here let us erect a monument to the dead species of our own times.

It is to be doubted whether, up to this hour, any man has made a list of the species of North American birds that have become extinct during the past sixty years. The specialists have no time to spare from their compound differential microscopes, and the bird-killers are too busy with shooting, netting and clubbing to waste any time on such trifles as exterminated species. What does a market-shooter care about birds that can not be killed a second time? As for the farmers, they are so busy raising hogs and prices that their best friends, the birds, get scant attention from them,—until a hen-hawk takes a chicken!

Down South, the negroes and poor whites may slaughter robins for food by the ten thousand; but does the northern farmer bother his head about a trifle of that kind? No, indeed. Will he contribute any real money to help put a stop to it? Ask him yourself.

Let us pause long enough to reckon up some of our expenditures in species, and in millions of individuals. Let us set down here, in cold blood, a list of the species of our own North American birds that have been totally exterminated in our own times. After that we will have something to say about other species that soon will be exterminated; and the second task is much greater than the first.

The Great Auk, —Plautus impennis, (Linn.), was a sea-going diving bird about the size of a domestic goose, related to the guillemots, murres and puffins. For a bird endowed only with flipper-like wings, and therefore absolutely unable to fly, this species had an astonishing geographic range. It embraced the shores of northern Europe to North Cape, southern Greenland, southern Labrador, and the Atlantic coast of North America as far south as Massachusetts. Some say, "as far south as Massachusetts, the Carolinas and Florida," but that is a large order, and I leave the A.O.U. to prove that if it can. In the life history of this bird, a great tragedy was enacted in 1800 by sailors, on Funk Island, north of Newfoundland, where men were landed by a ship, and spent several months slaughtering great auks and trying out their fat for oil. In this process, the bodies of thousands of auks were burned as fuel, in working up the remains of tens of thousands of others.

[Page†11]On Funk Island, a favorite breeding-place, the great auk was exterminated in 1840, and in Iceland in 1844. Many natives ate this bird with relish, and being easily captured, either on land or sea, the commercialism of its day soon obliterated the species. The last living specimen was seen in 1852, and the last dead one was picked up in Trinity Bay, Ireland, in 1853. There are about 80 mounted and unmounted skins in existence, four skeletons, and quite a number of eggs. An egg is worth about $1200 and a good mounted skin at least double that sum.

The Labrador Duck, —Camptorhynchus labradoricus, (Gmel.).—This handsome sea-duck, of a species related to the eider ducks of arctic waters, became totally extinct about 1875, before the scientific world even knew that its existence was threatened. With this species, the exact and final cause of its extinction is to this day unknown. It is not at all probable, however, that its unfortunate blotting out from our bird fauna was due to natural causes, and when the truth becomes known, it is very probable that the hand of man will be revealed.

The Labrador duck bred in Labrador, and once frequented our Atlantic coast as far south as Chesapeake Bay; but it is said that it never was very numerous, at least during the twenty-five years preceding its disappearance. About thirty-five skins and mounted museum specimens are all that remain to prove its former existence, and I think there is not even one skeleton.

The Pallas Cormorant, —Carbo perspicillatus, (Pallas).—In 1741, when the Russian explorer, Commander Bering, discovered the Bering or Commander Islands, in the far-north Pacific, and landed upon them, he also discovered this striking bird species. Its plumage both above and below was a dark metallic green, with blue iridescence on the neck and purple on the shoulders. A pale ring of naked skin around each eye suggested the Latin specific name of this bird. The Pallas cormorant became totally extinct, through causes not positively known, about 1852.

The Passenger Pigeon, —Ectopistes migratoria, (Linn.).—We place this bird in the totally-extinct class, not only because it is extinct in a wild state, but only one solitary individual, a twenty-year-old female in the Cincinnati Zoological Gardens, now remains alive. One living specimen and a few skins, skeletons and stuffed specimens are all that remain to show for the uncountable millions of pigeons that swarmed over the United States, only yesterday as it were!

There is no doubt about where those millions have gone. They went down and out by systematic, wholesale slaughter for the market and the pot, before the shotguns, clubs and nets of the earliest American pot-hunters. Wherever they nested they were slaughtered.

It is a long and shameful story, but the grisly skeleton of its Michigan chapter can be set forth in a few words. In 1869, from the town of Hartford, Mich., three car loads of dead pigeons were shipped to market each day for forty days, making a total of 11,880,000 birds. It is recorded that another Michigan town marketed 15,840,000 in two years. (See Mr. W.B. Mershon's book, "The Passenger Pigeon.")

[Page†12]Alexander Wilson, the pioneer American ornithologist, was the man who seriously endeavored to estimate by computations the total number of passenger pigeons in one flock that was seen by him. Here is what he has said in his "American Ornithology":

"To form a rough estimate of the daily consumption of one of these immense flocks, let us first attempt to calculate the numbers of that above mentioned, as seen in passing between Frankfort and the Indiana territory. If we suppose this column to have been one mile in breadth (and I believe it to have been much more) and that it moved at the rate of one mile in a minute, four hours, the time it continued passing, would make its whole length two hundred and forty miles. Again, supposing that each square yard of this moving body comprehended three pigeons; the square yards in the whole space multiplied by three would give 2,230,272,000 pigeons! An almost inconceivable multitude, and yet probably far below the actual amount."

"Happening to go ashore one charming afternoon, to purchase some milk at a house that stood near the river, and while talking with the people within doors, I was suddenly struck with astonishment at a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant darkness, which, on the first moment, I took for a tornado about to overwhelm the house and every thing around in destruction. The people observing my surprise, coolly said, 'It is only the pigeons!' On running out I beheld a flock, thirty or forty yards in width, sweeping along very low, between the house and the mountain or height that formed the second bank of the river. These continued passing for more than a quarter of an hour, and at length varied their bearing so as to pass over the mountains, behind which they disappeared before the rear came up.

"In the Atlantic States, though they never appear in such unparalleled multitudes, they are sometimes very numerous; and great havoc is then made amongst them with the gun, the clap-net, and various other implements of destruction. As soon as it is ascertained in a town that the pigeons are flying numerously in the neighborhood, the gunners rise en masse; the clap-nets are spread out on suitable situations, commonly on an open height in an old buckwheat field, four or five live pigeons, with their eyelids sewed up, [A] are fastened on a movable stick, a small hut of branches is fitted up for the fowler at the distance of forty or fifty yards. By the pulling of a string, the stick on which the pigeons rest is alternately elevated and depressed, which produces a fluttering of their wings, similar to that of birds alighting. This being perceived by the passing flocks, they descend with great rapidity, and finding corn, buckwheat, etc, strewed about, begin to feed, and are instantly, by the pulling of a cord, covered by the net. In this manner ten, twenty, and even thirty dozen have been caught [Page†13] at one sweep. Meantime the air is darkened with large bodies of them moving in various directions; the woods also swarm with them in search of acorns, and the thundering of musquetry is perpetual on all sides from morning to night. Wagon loads of them are poured into market, where they sell from fifty to twenty-five and even twelve cents per dozen; and pigeons become the order of the day at dinner, breakfast and supper, until the very name becomes sickening."

The range of the passenger pigeon covered nearly the whole United States from the Atlantic coast westward to the Rocky Mountains. A few bold pigeons crossed the Rocky Mountains into Oregon, northern California and Washington, but only as "stragglers," few and far between. The wide range of this bird was worthy of a species that existed in millions, and it was persecuted literally all along the line. The greatest slaughter was in Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania. In 1848 Massachusetts gravely passed a law protecting the netters of wild pigeons from foreign interference! There was a fine of $10 for damaging nets, or frightening pigeons away from them. This was on the theory that the pigeons were so abundant they could not by any possibility ever become scarce, and that pigeon-slaughter was a legitimate industry.

In 1867, the State of New York found that the wild pigeon needed protection, and enacted a law to that effect. The year 1868 was the last year in which great numbers of passenger pigeons nested in that State. Eaton, in "The Birds of New York," said that "millions of birds occupied the timber along Bell's Run, near Ceres, Alleghany County, on the Pennsylvania line."

In 1870, Massachusetts gave pigeons protection except during an "open season," and in 1878 Pennsylvania elected to protect pigeons on their nesting grounds.

The passenger pigeon millions were destroyed so quickly, and so thoroughly en masse, that the American people utterly failed to comprehend it, and for thirty years obstinately refused to believe that the species had been suddenly wiped off the map of North America. There was years of talk about the great flocks having "taken refuge in South America," or in Mexico, and being still in existence. There were surmises about their having all "gone out to sea," and perished on the briny deep.

A thousand times, at least, wild pigeons have been "reported" as having been "seen." These rumors have covered nearly every northern state, the whole of the southwest, and California. For years and years we have been patiently writing letters to explain over and over that the band-tailed pigeon of the Pacific coast, and the red-billed pigeon of Arizona and the southwest are neither of them the passenger pigeon, and never can be.

There was a long period wherein we believed many of the pigeon reports that came from the states where the birds once were most numerous; but that period has absolutely passed. During the past five years large cash [Page†14] rewards, aggregating about $5000, have been offered for the discovery of one nesting pair of genuine passenger pigeons. Many persons have claimed this reward (of Professor C.F. Hodge, of Clark University, Worcester, Mass.), and many claims have been investigated. The results have disclosed many mourning doves, but not one pigeon. Now we understand that the quest is closed, and hope has been abandoned.

The passenger pigeon is a dead species. The last wild specimen (so we believe) that ever will reach the hands of man, was taken near Detroit, Michigan, on Sept. 14, 1908, and mounted by C. Campion. That is the one definite, positive record of the past ten years.

The fate of this species should be a lasting lesson to the world at large. Any wild bird or mammal species can be exterminated by commercial interests in twenty years time, or less.

The Eskimo Curlew, —Numenius borealis, (Forst.). This valuable game bird once ranged all along the Atlantic coast of North America, and wherever found it was prized for the table. It preferred the fields and meadows to the shore lines, and was the companion of the plovers of the uplands, especially the golden plover. "About 1872," says Mr. Forbush, "there was a great flight of these birds on Cape Cod and Nantucket. They were everywhere; and enormous numbers were killed. They could be bought of boys at six cents apiece. Two men killed $300 worth of these birds at that time."

Apparently, that was the beginning of the end of the "dough bird," which was another name for this curlew. In 1908 Mr. G.H. Mackay stated that this bird and the golden plover had decreased 90 per cent in fifty years, and in the last ten years of that period 90 per cent of the remainder had gone. "Now (1908)," says Mr. Forbush, "ornithologists believe that the Eskimo curlew is practically extinct, as only a few specimens have been recorded since the beginning of the twentieth century." The very last record is of two specimens collected at Waco, York County, Nebraska, in March, 1911, and recorded by Mr. August Eiche. Of course, it is possible that other individuals may still survive; but so far as our knowledge extends, the species is absolutely dead.

In the West Indies and the Guadeloupe Islands, five species of macaws and parrakeets have passed out without any serious note of their disappearance on the part of the people of the United States. It is at least time to write brief obituary notices of them.

We are indebted to the Hon. Walter Rothschild, of Tring, England, for essential facts regarding these species as set forth in his sumptuous work "Extinct Birds".

The Cuban Tricolored Macaw, —Ara tricolor, (Gm.). In 1875, when the author visited Cuba and the Isle of Pines, he was informed by Professor Poey that he was "about ten years too late" to find this fine species alive. It was exterminated for food purposes, about 1864, and only four specimens are known to be in existence.

![Exterminated By Civilized Man 1840-1910 [SACRED TO THE

MEMORY OF THE NORTH AMERICAN Great Auk Pallas Cormorant Labrador Duck

Passenger Pigeon Eskimo Curlew Cuban Tricolor Macaw Gosse's Macaw

Guadeloupe Macaw Yellow Winged Green Parrot Purple Guadaloupe Parakeet

Carolina Parakeet EXTERMINATED BY CIVILIZED MAN 1840-1910]](images/img05.png)

Gosse's Macaw, —Ara gossei, (Roth.).—This species once inhabited the Island of Jamaica. It was exterminated about 1800, and so far as known not one specimen of it is in existence.

Guadeloupe Macaw, —Ara guadeloupensis, (Clark).—All that is known of the life history of this large bird is that once it inhabited the Guadeloupe Islands. The date and history of its disappearance are both unknown, and there is not one specimen of it in existence.

Yellow-Winged Green Parrot, —Amazona olivacea, (Gm.).—Of the history of this Guadeloupe species, also, nothing is known, and there appear to be no specimens of it in existence.

Purple Guadeloupe Parrakeet, —Anodorhynchus purpurescens, (Rothschild).—This is another dead species, that once lived in the Guadeloupe Islands, and passed away silently and unnoticed at the time, leaving no records of its existence, and no specimens.

The Carolina Parrakeet, —Conuropsis carolinensis, (Linn.), brings us down to the present moment. To this charming little green-and-yellow bird, we are in the very act of bidding everlasting farewell. Ten specimens remain alive in captivity, six of which are in the Cincinnati Zoological Garden, three are in the Washington Zoological Park and one is in the New York Zoological Park.

Regarding wild specimens, it is possible that some yet remain, in some obscure and neglected corner of Florida; but it is extremely doubtful whether the world ever will find any of them alive. Mrs. Minnie Moore Willson, of Kissimee, Fla. reports the species as totally extinct in Florida. Unless we would strain at a gnat, we may just as well enter this species in the dead class; for there is no reason to hope that any more wild specimens ever will be found.

The former range of this species embraced the whole southeastern and central United States. From the Gulf it extended to Albany, N.Y., northern Ohio and Indiana, northern Iowa, Nebraska, central Colorado and eastern Texas, from which it will be seen that once it was widely distributed. It was shot because it was destructive to fruit and for its plumage, and many were trapped alive, to be kept in captivity. I know that one colony, near the mouth of the Sebastian River, east coast of Florida, was exterminated in 1898 by a local hunter, and I regret to say that it was done in the hope of selling the living birds to a New York bird-dealer. By holding bags over the holes in which the birds were nesting, the entire colony, of about 16 birds, was caught.

Everywhere else than in Florida, the Carolina parrakeet has long been extinct. In 1904 a flock of 13 birds was seen near Lake Okechobee; but in Florida many calamities can overtake a flock of birds in eight years. The birds in captivity are not breeding, and so far as perpetuation by them is concerned, they are only one remove from mounted museum specimens. This parrakeet is the only member of its order that ranged into the United States during our own times, and with its disappearance the Order Psittaciformes totally disappears from our country.

In the world of human beings, murder is the most serious of all crimes. To take from a man that which no one ever can restore to him, his life, is murder; and its penalty is the most severe of all penalties.

There are circumstances under which the killing of a wild animal may be so wanton, so revolting and so utterly reprehensible that the act may justly be classed as murder. The man who kills a walrus from the deck of a steamer that he knows will not stop; the man who wantonly killed the whole colony of hippopotami that Mr. Dugmore photographed in life; the man who last winter shot bull elk in Wyoming for their two ugly and shapeless teeth, and the man who wantonly shot down a half-tame deer "for fun" near Carmel, Putnam County, New York, in the summer of 1912,—all were guilty of murdering wild animals.

The murder of a wild animal species consists in taking from it that which man with all his cunning and all his preserves and breeding can not give back to it,—its God-given place in the ranks of Living Things. Where is man's boasted intelligence, or his sense of proportion, that every man does not see the monstrous moral obliquity involved in the destruction of a species!

If the beautiful Taj Mehal at Agra should be destroyed by vandals, the intelligent portion of humanity would be profoundly shocked, even though the hand of man could at will restore the shrine of sorrowing love. To-day the great Indian rhinoceros, certainly one of the most wonderful four-footed animals still surviving, is actually being exterminated; and even the people of India and England are viewing it with an indifference that is appalling. Of course there are among Englishmen a great many sportsmen and several zoologists who really care; but they do not constitute one-tenth of one per-cent of the men who ought to care!

In the museums, we stand in awe and wonder before the fossil skeleton of the Megatherium, and the savants struggle to unveil its past, while the equally great and marvelous Rhinoceros indicus is being rushed into oblivion. We marvel at the fossil shell of the gigantic turtle called Collosochelys atlas, while the last living representatives of the gigantic land tortoises are being exterminated in the Galapagos Islands and the Sychelles, for their paltry oil and meat; and only one man (Hon. Walter Rothschild) is doing aught to save any of them in their haunts, where they can breed. The dodo of Mauritius was exterminated by swine, whose bipedal descendants have exterminated many other species since that time.

[Page†18]A failure to appreciate either the beauty or the value of our living birds, quadrupeds and fishes is the hall-mark of arrested mental development and ignorance. The victim is not always to blame; but in this practical world the cornerstone of legal jurisprudence is the inexorable principle that "ignorance of the law excuses no man."

These pages are addressed to my countrymen, and the world at large, not as a reproach upon the dead Past which is gone beyond recall, but in the faint hope of somewhere and somehow arousing forces that will reform the Present and save the Future. The extermination of wild species that now is proceeding throughout the world, is a dreadful thing. It is not only injurious to the economy of the world, but it is a shame and a disgrace to the civilized portion of the human race.

It is of little avail that I should here enter into a detailed description of each species that now is being railroaded into oblivion. The bookshelves of intelligent men and women are filled with beautiful and adequate books on birds and quadrupeds, wherein the status of each species may be determined, almost without effort. There is time and space only in which to notice the most prominent of the doomed species, and perhaps discuss a few examples by way of illustration. Here is a

| Partial List Of North American Birds Threatened With Early Extermination | |

| Whooping Crane | Pectoral Sandpiper |

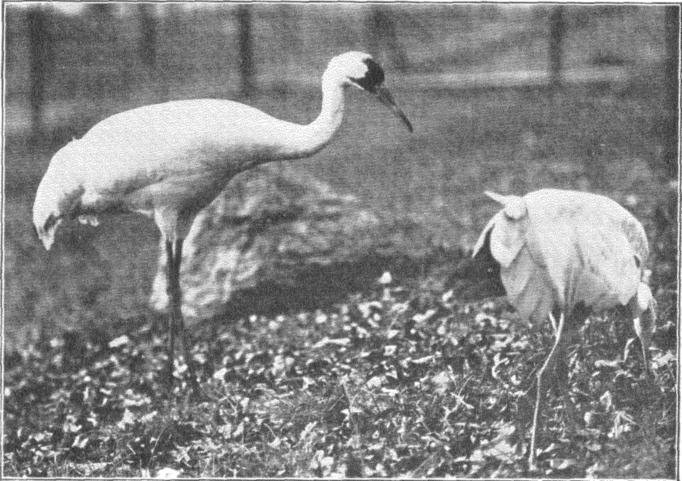

| Trumpeter Swan | Black-Capped Petrel |

| American Flamingo | American Egret |

| Roseate Spoonbill | Snowy Egret |

| Scarlet Ibis | Wood Duck |

| Long-Billed Curlew | Band-Tailed Pigeon |

| Hudsonian Godwit | Heath Hen |

| Upland Plover | Sage Grouse |

| Red-Breasted Sandpiper | Prairie Sharp-Tail |

| Golden Plover | Pinnated Grouse |

| Dowitcher | White-Tailed Kite |

| Willet | |

The Whooping Crane. —This splendid bird will almost certainly be the next North American species to be totally exterminated. It is the only new world rival of the numerous large and showy cranes of the old world; for the sandhill crane is not in the same class as the white, black and blue giants of Asia. We will part from our stately Grus americanus with profound sorrow, for on this continent we ne'er shall see his like again.

The well-nigh total disappearance of this species has been brought close home to us by the fact that there are less than half a dozen individuals alive in captivity, while in a wild state the bird is so rare as to be quite unobtainable. For example, for nearly five years an English [Page†19] gentlemen has been offering $1,000 for a pair, and the most enterprising bird collector in America has been quite unable to fill the order. So far as our information extends, the last living specimen captured was taken six or seven years ago. The last wild birds seen and reported were observed by Ernest Thompson Seton, who saw five below Fort McMurray, Saskatchewan, October 16th, 1907, and by John F. Ferry, who saw one at Big Quill Lake, Saskatchewan, in June, 1909.

The range of this species once covered the eastern two-thirds of the continent of North America. It extended from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from Great Bear Lake to Florida and Texas. Eastward of the Mississippi it has for twenty years been totally extinct, and the last specimens taken alive were found in Kansas and Nebraska.

WHOOPING CRANES IN THE ZOOLOGICAL PARK

Very Soon this Species will Become Totally Extinct.

The Trumpeter Swan. —Six years ago this species was regarded as so nearly extinct that a doubting ornithological club of Boston refused to believe on hearsay evidence that the New York Zoological Park contained a pair of living birds, and a committee was appointed, to investigate in person, and report. Even at that time, skins were worth all the way from $100 to $150 each; and when swan skins sell at either of those figures it is because there are people who believe that the species either is on the verge of extinction, or has passed it. The pair referred to above [Page†20] was acquired in 1900. Since that time, Dr. Leonard C. Sanford procured in 1910 two living birds from a bird dealer who obtained them on the coast of Virginia. We have done our utmost to induce our pair to breed, but without any further results than nest-building.

The loss of the trumpeter swan (Olor americanus) will not be so great, nor felt so keenly, as the blotting out of the whooping crane. It so closely resembles the whistling swan that only an ornithologist can recognize the difference, a yellow spot on the side of the upper mandible, near its base. The whistling swan yet remains in fair numbers, but it is to be feared that soon it will go as the trumpeter has gone.

The American Flamingo, Scarlet Ibis And Roseate Spoonbill are three of the most beautiful and curious water-haunting birds of the tropics. Once all three species inhabited portions of the southern United States; but now all three are gone from our star-spangled bird fauna. The brilliant scarlet plumage of the flamingo and ibis, and the exquisite pink rose-color and white of the spoonbill naturally attracted the evil eyes of the "milliner's taxidermists" and other bird-butchers. From Florida these birds quickly vanished. The six great breeding colonies of Flamingoes on Andros Island, Bahamas, have been reduced to two, and from Prof. E.A. Goeldi, of the State Museum Goeldi, Para, Brazil, have come bitter complaints of the slaughter of scarlet ibises in South America by plume-hunters in European pay.

I know not how other naturalists regard the future of the three species named above, but my opinion is that unless the European feather trade is quickly stopped as to wild plumage, they are absolutely certain to be shot into total oblivion, within a very few years. The plumage of these birds has so much commercial value, for fishermen's flies as well as for women's hats, that the birds will be killed as long as their feathers can be sold and any birds remain alive.

Zoologically, the flamingo is the most odd and interesting bird on the American continent except the emperor penguin. Its beak baffles description, its long legs and webbed feet are a joke, its nesting habits are amazing, and its food habits the despair of most zoological-garden keepers. Millions of flamingos inhabit the shores of a number of small lakes in the interior of equatorial East Africa, but that species is not brilliant scarlet all over the neck and head, as is the case with our species.

If the American flamingo, scarlet ibis and roseate spoonbill, one or all of them, are to be saved from total extinction, efforts must be made in each of the countries in which they breed and live. Their preservation is distinctly a burden upon the countries of South America that lie eastward of the Andes, and on Yucatan, Cuba and the Bahamas. The time has come when the Government of the Bahama Islands should sternly forbid the killing of any more flamingos, on any pretext whatever; and if the capture of living specimens for exhibition purposes militates against the welfare of the colonies, they should forbid that also.

The Upland Plover, Or "Bartramian Sandpiper." —Apparently this is the next shore-bird species that will follow the Eskimo curlew into [Page†21] oblivion. Four years ago,—a long period for a species that is on the edge of extermination,—Mr. E.H. Forbush [B] wrote of it as follows:

"The Bartramian Sandpiper, commonly known as the Upland Plover, a bird which formerly bred on grassy hills all over the State and migrated southward along our coasts in great flocks, is in imminent danger of extirpation. A few still breed in Worcester and Berkshire Counties, or Nantucket, so there is still a nucleus which, if protected, may save the species. Five reports from localities where this bird formerly bred give it as nearing extinction, and four as extinct. This is one of the most useful of all birds in grass land, feeding largely on grasshoppers and cutworms. It is one of the finest of all birds for the table. An effort should be made at once to save this useful species."

The Black-Capped Petrel, (Aestrelata hasitata). —This species is already recorded in the A.O.U. "Check list" as extinct; but it appears that this may not as yet be absolutely true. On January 1, 1912, a strange thing happened. A much battered and exhausted black-capped petrel was picked up alive in Central Park, New York, taken to the menagerie, and kept there during the few days that it survived. When it died it was sent to the American Museum; and this may easily prove to be the last living record for that species. In reality, this species might as well be listed with those totally extinct. Formerly it ranged from the Antilles to Ohio and Ontario, and the causes of its blotting out are not yet definitely known.

This ocean-going bird once had a wide range overseas in the temperate areas of the North Atlantic. It is recorded from Ulster County, New York, New Hampshire, Kentucky, Ohio, Virginia and Florida. It was about of the size of the common tern.

The California Condor, (Gymnogyps californianus). —I feel that the existence of this species hangs on a very slender thread. This is due to its alarmingly small range, the insignificant number of individuals now living, the openness of the species to attack, and the danger of its extinction by poison. Originally this remarkable bird,—the largest North American bird of prey,—ranged as far northward as the Columbia River, and southward for an unknown distance. Now its range is reduced to seven counties in southern California, although it is said to extend from Monterey Bay to Lower California, and eastward to Arizona.

Regarding the present status and the future of this bird, I have been greatly disturbed in mind. When a unique and zoologically important species becomes reduced in its geographic range to a small section of a single state, it seems to me quite time for alarm. For some time I have counted this bird as one of those threatened with early extermination, and as I think with good reason. In view of the swift calamities that now seem able to fall on species like thunderbolts out of clear skies, and wipe them off the earth even before we know that such a fate is [Page†22] impending, no species of seven-county distribution is safe. Any species that is limited to a few counties of a single state is liable to be wiped out in five years, by poison, or traps, or lack of food.

CALIFORNIA CONDOR

Now Living in the New York Zoological Park

On order to obtain the best and also the most conservative information regarding this species, I appealed to the Curator of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, of the University of California. Although written in the mountain wilds, I promptly received the valuable contribution that appears below. As a clear, precise and conservative survey of an important species, it is really a model document.

By Joseph Grinnell

"To my knowledge, the California Condor has been definitely observed within the past five years in the following California counties: Los Angeles, Ventura, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Monterey, Kern, and Tulare. In parts of Ventura, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Kern counties the species is still fairly common, for a large bird, probably equal in numbers to the golden eagle in those regions that are suited to [Page†23] it. By suitable country I mean cattle-raising, mountainous territory, of which there are still vast areas, and which are not likely to be put to any other use for a very long time, if ever, on account of the lack of water.

"While in Kern County last April, I was informed by a reliable man who lives near the Tejon Rancho that he had counted twenty-five condors in a single day, since January 1 of the present year. These were on the Tejon Rancho, which is an enormous cattle range covering parts of the Tehachapi and San Emigdio Mountains.

"Our present state law provides complete protection for the condor and its eggs; and the State Fish and Game Commission, in granting permits for collectors, always adds the phrase—'except the California condor and its eggs.' I know of two special permits having been issued, but neither of these were used; that is, no 'specimens' have been taken since 1908, as far as I am aware.

"In my travels about the state, I have found that practically everyone knows that the condor is protected. Still, there is always the hunting element who do not hesitate to shoot anything alive and out of the ordinary, and a certain percentage of the condors are doubtless picked off each year by such criminals. It is possible, also, that the mercenary egg-collector continues to take his annual rents, though if this is done it is kept very quiet. It is my impression that the present fatalities from all sources are fully balanced by the natural rate of increase.

"There is one factor that has militated against the condor more than any other one thing; namely, the restriction in its food source. Its forage range formerly included most of the great valleys adjacent to its mountain retreats. But now the valleys are almost entirely devoted to agriculture, and of course far more thickly settled than formerly.

"The mountainous areas where the condor is making its last stand seem to me likely to remain adapted to the bird's existence for many years,—fifty years, if not longer. Of course, this is conditional upon the maintenance and enforcement of the present laws. There is also the enlightenment of public sentiment in regard to the preservation of wild life, which I believe can be depended upon. This is a matter of general education, which is, fortunately, and with no doubt whatever, progressing at a quite perceptible rate.

"Yes; I should say that the condor has a fair chance to survive, in limited numbers.

"Another bird which in my opinion is far nearer extinction than the condor, so far as California is concerned, is the white-tailed kite. This is a perfectly harmless bird, but one which harries over the marshes, where it has been an easy target for the idle duck-hunter. Then, too, its range was limited to the valley bottoms, where human settlement is increasingly close. I know of only two live pairs within the state last year!

"Finally, let me remark that the rate of increase of the California condor is not one whit less than that of the band-tailed pigeon! Yet, [Page†24] there is no protection at all for the latter in this state, even in the nesting season; and thousands were shot last spring, in the unprecedented concentration of the species in the southern coast counties. (See Chambers in The Condor for May, 1912, p. 108.)"

The California Condor is one of the only two species of condor now living, and it is the only one found in North America. As a matter of national pride, and a duty to posterity, the people of the United States can far better afford to lose a million dollars from their national treasury than to allow that bird to become extinct. Its preservation for all coming time is distinctly a white man's burden upon the state of California. The laws now in force for the condor's protection are not half adequate! I think there is no law by which the accidental poisoning of those birds, by baits put out for coyotes and foxes, can be stopped. A law to prevent the use of poisoned meat baits anywhere in southern California, should be enacted at the next session of California's legislature. The fine for molesting a condor should be raised to $500, with a long prison-term as an alternative. A competent, interested game warden should be appointed solely for the protection of the condors. It is time to count those birds, keep them under observation, and have an annual report upon their condition.

The Heath Hen. —But for the protection that has been provided for it by the ornithologists of Massachusetts, and particularly Dr. George W. Field, William Brewster and John E. Thayer, the heath hen or eastern pinnated grouse would years ago have become totally extinct. New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts began to protect that species entirely too late. It was given five-year close seasons, without avail. Then it was given ten-year close seasons, but it was too late!

To-day, the species exists only in one locality, the island of Martha's Vineyard, and concerning its present status, Mr. Forbush has recently furnished us the following clear statement: