The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mother Stories, by Maud Lindsay This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Mother Stories Author: Maud Lindsay Illustrator: Sarah Noble-Ives Release Date: May 28, 2005 [EBook #15929] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOTHER STORIES *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

| "Mother, a story told at the right time |

| Is a looking-glass for the mind." |

| Froebel. |

I have endeavored to write, for mothers and dear little children, a few simple stories, embodying some of the truths of Froebel's Mother Play.

The Mother Play is such a vast treasure house of Truth, that each one who seeks among its stores may bring to light some gem; and though, perhaps, I have missed its diamonds and rubies, I trust my string of pearls may find acceptance with some mother who is trying to live with her children.

I have written my own mottoes, with a few exceptions, that I might emphasize the particular lesson which I endeavor to teach in the story; for every motto in the Mother Play comprehends so much that it is impossible to use the whole for a single subject. From "The Bridge" for instance, which is replete with lessons, I have taken only one,—for the story of the "Little Traveler."

Most of these stories have been told and retold to little children, and are surrounded, in my eyes, by a halo of listening faces.

"Mrs. Tabby Gray" is founded on a true story of a favorite cat. "The Journey" is a new version of the old Stage Coach game, much loved by our grandmothers; and I am indebted to some old story, read in childhood, for the suggestion of "Dust Under the Rug," which was a successful experiment in a kindergarten to test the possibility of interesting little children in a story after the order of Grimm, with the wicked stepmother and her violent daughter eradicated.

Elizabeth Peabody says we are all free to look out of each other's windows; and so I place mine at the service of all who care to see what its tiny panes command.

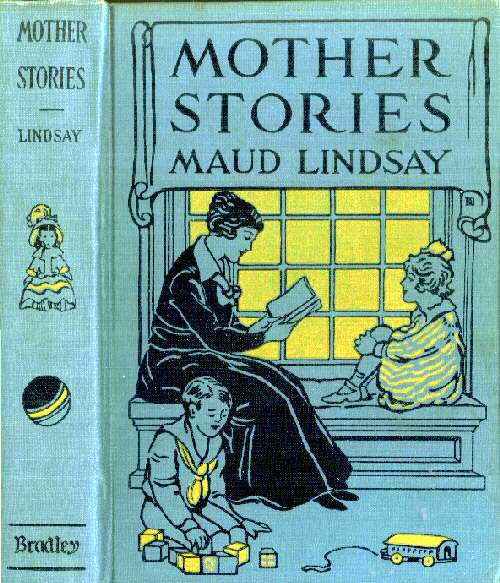

One morning Jan waked up very early, and the first thing he saw when he opened his eyes was his great kite in the corner. His big brother had made it for him; and it had a smiling face, and a long tail that reached from the bed to the fireplace. It did not smile at Jan that morning though, but looked very sorrowful and seemed to say "Why was I made? Not to stand in a corner, I hope!" for it had been finished for two whole days and not a breeze had blown to carry it up like a bird in the air.

Jan jumped out of bed, dressed himself, and ran to the door to see if the windmill on the hill was at work; for he hoped that the wind had come in the night. But the mill was silent and its arms stood still. Not even a leaf turned over in the yard.

The windmill stood on a high hill where all the people could see it, and when its long arms went whirling around every one knew that there was no danger of being hungry, for then the Miller was busy from morn to night grinding the grain that the farmers brought him.

When Jan looked out, however, the Miller had nothing to do, and was standing in his doorway, watching the clouds, and saying to himself (though Jan could not hear him):—

He sighed as he spoke, for he looked down in the village, and saw the Baker in neat cap and apron, standing idle too.

The Baker's ovens were cold, and his trays were clean, and he, too, was watching the sky, and saying:—

Jan heard every word that the Baker said, for he lived next door to him; and he felt so sorry for his good neighbor that he wanted to tell him so. But before he had time to speak, somebody else called out from across the street:—

This was the Washerwoman who was hanging out her clothes. Jan could see his own Sunday shirt, with ruffles, hanging limp on her line, and it was as white as a snowflake, sure enough!

"Come over, little neighbor," cried the Washerwoman, when she saw Jan. "Come over, little neighbor, and help me work to-day!" So, as soon as Jan had eaten his breakfast, he ran over to carry her basket for her. The basket was heavy, but he did not care; and as he worked he heard some one singing a song, with a voice almost as loud and as strong as the wind.

Jan and the Washerwoman and all the neighbors looked out to see who was singing so cheerily, and it was the Sea-captain whose white ship Jan had watched in the harbor. The ship was laden with linen and laces for fine ladies, but it could not go till the wind blew. The Captain was impatient to be off, and so he walked about town, singing his jolly song to keep himself happy.

Jan thought it was a beautiful song, and when he went home he tried to sing it himself. He did not know all the words, but he put his hands in his pockets and swelled out his little chest and sang in as big a voice as he could: "Yeo ho! my lads, yeo ho!"

While he sang, something kissed him on the cheek; and when he turned to see what it was his hat spun off into the yard as if it were enchanted; and when he ran to pick his hat up he heard a whispering all through the town. He looked up, and he looked down, and on every side, but saw nobody! At last the golden weather-vane on the church tower called down:—

"Foolish child, it is the wind from out of the east."

The trees had been the first to know of its coming, and they were bowing and bending to welcome it; while the leaves danced off the branches and down the hill, in a whirl of delight.

The windmill's arms whirled round, oh! so fast, and the wheat was ground into white flour for the Baker, who kindled his fires and beat his eggs in the twinkling of an eye; and he was not quicker than the Sea-captain, who loosed his sails in the fresh'ning gales, just as he had said he would, and sailed away to foreign lands.

Jan watched him go, and then ran in great haste to get his kite; for the petticoats on the Washerwoman's clothesline were puffed up like balloons, and all the world was astir.

"Now I'm in my proper place," said the kite as it sailed over the roofs of the houses, over the tree tops, over the golden weather vane, and even over the windmill itself. Higher, higher, higher it flew, as if it had wings; till it slipped away from the string, and Jan never saw it again, and only the wind knew where it landed at last.

Mrs. Tabby Gray, with her three little kittens, lived out in the barn where the hay was stored. One of the kittens was white, one was black, and one gray, just like her mother, who was called Tabby Gray from the color of her coat.

These three little kittens opened their eyes when they grew old enough, and thought there was nothing so nice in all this wonderful world as their own dear mother, although she told them of a great many nice things, like milk and bread, which they should have when they could go up to the big house where she had her breakfast, dinner, and supper.

Every time Mother Tabby came from the big house she had something pleasant to tell. "Bones for dinner to-day, my dears," she would say, or "I had a fine romp with a ball and the baby," until the kittens longed for the time when they could go too.

One day, however, Mother Cat walked in with joyful news.

"I have found an elegant new home for you," she said, "in a very large trunk where some old clothes are kept; and I think I had better move at once."

Then she picked up the small black kitten, without any more words, and walked right out of the barn with him.

The black kitten was astonished, but he blinked his eyes at the bright sunshine, and tried to see everything.

Out in the barnyard there was a great noise, for the white hen had laid an egg, and wanted everybody to know it; but Mother Cat hurried on, without stopping to inquire about it, and soon dropped the kitten into the large trunk. The clothes made such a soft, comfortable bed, and the kitten was so tired after his exciting trip, that he fell asleep, and Mrs. Tabby trotted off for another baby.

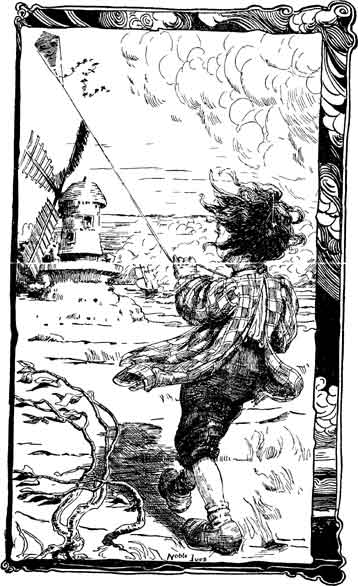

While she was away, the lady who owned the trunk came out in the hall; and when she saw that the trunk was open, she shut it, locked it, and put the key in her pocket, for she did not dream that there was anything so precious as a kitten inside.

As soon as the lady had gone upstairs Mrs. Tabby Gray came back, with the little white kitten; and when she found the trunk closed, she was terribly frightened. She put the white kitten down and sprang on top of the trunk and scratched with all her might, but scratching did no good. Then she jumped down and reached up to the keyhole, but that was too small for even a mouse to pass through, and the poor mother mewed pitifully.

What was she to do? She picked up the white kitten, and ran to the barn with it. Then she made haste to the house again, and went upstairs to the lady's room. The lady was playing with her baby and when Mother Cat saw this she rubbed against her skirts, and cried: "Mee-ow, mee-ow! You have your baby, and I want mine! Mee-ow, mee-ow!"

By and by the lady said: "Poor Kitty! she must be hungry"; and she went down to the kitchen and poured sweet milk in a saucer, but the cat did not want milk. She wanted her baby kitten out of the big black trunk, and she mewed as plainly as she could: "Give me my baby—give me my baby, out of your big black trunk!"

The kind lady decided that she must be thirsty: "Poor Kitty, I will give you water"; but when she set the bowl of water down Mrs. Tabby Gray mewed more sorrowfully than before. She wanted no water,—she only wanted her dear baby kitten; and she ran to and fro, crying, until, at last, the lady followed her; and she led the way to the trunk.

"What can be the matter with this cat?" said the lady; and she took the trunk key out of her pocket, put it in the lock, unlocked the trunk, raised the top—and in jumped Mother Cat with such a bound that the little black kitten waked up with a start.

"Purr, purr, my darling child," said Mrs. Tabby Gray, in great excitement; "I have had a dreadful fright!" and before the black kitten could ask one question she picked him up and started for the barn.

The sun was bright in the barnyard and the hens were still chattering there; but the black kitten was glad to get back to the barn. His mother was glad, too; for, as she nestled down in the hay with her three little kittens, she told them that a barn was the best place after all to raise children.

And she never afterwards changed her mind.

Mother and Father Pigeon lived with their two young pigeons in their home, built high on a post in the king's barnyard. Every bright morning they would fly away through the beautiful sunshine wherever they pleased, but, when evening came, they were sure to come to the pigeon-house again.

One evening, when they were talking together in their sweet, cooing way, Mother Pigeon said:—

"We each have a story to tell, I know; so let each one take his turn, and Father Pigeon begin."

Then Father Pigeon said:—

"To-day I have been down to the shining little stream that runs through the wood. The green ferns grow on either side of it, and the water is cool, cool, cool! for I dipped my feet into it, and wished that you all were there."

"I know the stream," cooed Mother Pigeon. "It turns the wheels of the mills as it hurries along, and is busy all day on its way to the river."

"To-day I have talked with the birds in the garden," said Sweet Voice, one of the young pigeons, "the thrush, the blackbird, and bluebird, and all. They sang to me and I cooed to them, and together we made the world gay. The bluebird sang of the sunshine, and the blackbird of the harvest; but the thrush sang the sweetest song. It was about her nest in the tree."

"I heard you all," said Fleet Wing, the other young pigeon; "for I sat and listened on the high church tower. I was so high up, there, that I thought I was higher than anything else; but I saw the great sun shining in the sky, and the little white clouds, like sky pigeons, sailing above me. Then, looking down, I saw, far away, this white pigeon-house; and it made me very glad, for nothing that I saw was so lovely as home."

"I never fly far away from home," said Mother Pigeon, "and to-day I visited in the chicken yard. The hens were all talking, and they greeted me with 'Good morning! Good morning!' and the turkey gobbled 'Good morning!' and the rooster said 'How do you do?' While I chatted with them a little girl came out with a basket of yellow corn, and threw some for us all. When I was eating my share, I longed for my dear ones. And now good night," cooed Mother Pigeon, "it is sleepy time for us all."

"Coo, coo! Good night!" answered the others; and all was still in the pigeon-house.

Now over in the palace, where the king, and queen, and their one little daughter lived, there was the sound of music and laughter; but the king's little daughter was sad, for early the next morning her father, the king, was to start on a journey, and she loved him so dearly that she could not bear to have him leave her.

The king's little daughter could not go out in the sunshine like Sweet Voice and Fleet Wing, but lay all day within the palace on her silken cushions; for her fine little feet, in their satin slippers, were always too tired to carry her about, and her thin, little face was as white as a jasmine flower.

The king loved her as dearly as she loved him; and when he saw that she was sad, he tried to think of something to make her glad after he had gone away. At last he called a prince, and whispered something to him. The prince told it to a count, and the count to a gentleman-in-waiting.

The gentleman-in-waiting told a footman, and the footman told somebody else, and at last, the boy who waited on the cook heard it.

Early next morning he went to the pigeon-house, where Mother and Father Pigeon and their two young pigeons lived; and putting his hand through a door, he took Sweet Voice and Fleet Wing out, and dropped them into a basket.

Poor Sweet Voice, and Fleet Wing! They were so frightened that they could not coo! They sat very close to each other in the covered basket, and wondered when they would see their mother and father and home again.

All the time, as they sat close together in the basket and wondered, they were being taken away from home; for the king had started on his journey, and one of his gentlemen was carrying the basket, very carefully, with him on his horse.

At last the horses stood still and the basket was taken to the king; and when he opened it, the two little pigeons looked up and saw that the sun was high in the sky, and that they were far from home.

When they saw that they were far from home, they were more frightened than before; but the king spoke so kindly and smoothed their feathers so gently, that they knew he would take care of them.

Then the king took two tiny letters tied with lovely blue ribbon out of his pocket; and, while his gentlemen stood by to see, he fastened one under a wing of each little pigeon.

"Fly away, little pigeons!" he cried; and he tossed them up toward the sky. "Fly away, and carry my love to my little daughter!"

Fleet Wing, and Sweet Voice spread their wings joyfully, for they knew that they were free! free! and they wanted to go home.

Everywhere they saw green woods, instead of the red roofs and shining windows of the town, and Sweet Voice was afraid; but Fleet Wing said:—

"I saw these woods from the tall church steeple. Home is not so far away as we thought."

Then they lost no time in talking, but turned their heads homeward; and as they flew the little gray squirrels that ran about in the woods called out to ask them to play, but the pigeons could not stay.

The wood dove heard them, and called from her tree: "Little cousins, come in!" But the pigeons thanked her and hurried on.

"Home is not so far away," said Fleet Wing; but he began to fear that he had missed the way, and Sweet Voice was so tired that she begged him to fly on alone.

Fleet Wing would not listen to this; and, as they talked, they came to a little stream of water with green ferns growing all about, and they knew that it must be the very stream that Father Pigeon loved. Then they cooled their tired feet in the fresh water, and cooed for joy; for they knew that they were getting nearer, nearer, nearer home, all the time.

Sweet Voice was not afraid then; and as they flew from the shelter of the woods, they saw the tall church steeple with its golden weather vane.

The sun was in the west, and the windows were all shining in its light, when Fleet Wing and Sweet Voice reached the town. The little children saw them and called: "Stay with us, pretty pigeons." But Sweet Voice and Fleet Wing did not rest until they reached the white pigeon house, where Mother and Father Pigeon were waiting.

The cook's boy was waiting, too, and the little pigeons were taken in to see the king's little daughter. When she found the letters which they carried under their wings, she laughed with delight; and Fleet Wing and Sweet Voice were very proud to think that they had brought glad news to their princess.

They told it over and over again out in the pigeon-house, and Mother and Father Pigeon were glad, too.

In the morning, the birds in the garden were told of the wonderful things that had happened to Fleet Wing and Sweet Voice; and even the hens and chickens had something to say when they heard the news.

The thrush said that it all made her think of her own sweet song; and she sang it again to them:—

There once lived a little maiden to whom God had given a wonderful light, which made her whole life bright.

When she was a wee baby it shone on her face in a beautiful smile, and her mother cried:—

"See! the angels have been kissing her!" And when she grew older it lighted up her eyes like sunshine, and gleamed on her forehead like a star.

All lovely things that loved light, loved her. The soft-cooing pigeons came at her call. The roses climbed up to her windows to peep at her, and the birds of the air, and the butterflies, that looked like enchanted sunbeams, would circle about her head.

Her father was king of a country; and though she was not so tall as the tall white lily in the garden, or the weeds that grew outside, she had servants to wait on her, and grant her every wish, as if she were a queen.

She was dearer to her father and mother than all else that they possessed; and there was no happier king or queen or little maiden in any kingdom of the world, till one sad day when the king's enemies came upon them like a whirlwind, and changed their joy to sorrow.

Their palace was seized, the servants were scattered, and the king and queen were carried away to a dark prison-house, where they sat and wept for their little daughter, for they knew not where she was.

No one knew but the old nurse, who had nursed the king himself. She had carried the child away, unnoticed amid the noise and strife, and set her in safety outside the palace walls.

"Fly, precious one!" she cried, as she left her there. "Fly! for the enemy is upon us!" And the little maiden started out in the world alone.

She knew not where to go; so she wandered away through the fields and waste places, where nobody lived and only the grasshoppers seemed glad. But she was not afraid,—no! not even when she came to a great forest, at evening;—for she carried her light with her.

'T is true that once she thought she saw a threatening giant waiting by the dusky path; but, when her light shone on it, it was only a pine tree, stretching out its friendly arms; and she laughed so merrily that all the woods laughed too.

"Who are you? Who are you?" asked an owl, blinking his eyes at the brightness of her face; and a little rabbit, startled by the sound, sprang from its hiding place in the bushes and fell trembling at her feet.

"Alas!" it panted as she bent in pity to offer help, "Alas! the hunters with their dogs and guns pursue me! But you flee, too! How can you help me?" But the child took the tiny creature in her arms and held it close; and when the dogs rushed through the tanglewood, they saw the light that lighted up her eyes like sunshine and gleamed on her forehead like a star, and came no further.

Then deeper into the great forest she went, bearing the rabbit still; and the wild beasts heard her footsteps, and waited for her coming.

"Hush!" said the fox, "she is mine; for I will lead her from the path into the tanglewood!"

"Nay, she is mine!" howled the wolf; "for I will follow on her footsteps!"

"Mine! mine!" screamed the tiger; "for I will spring upon her in the darkness, and she cannot escape me!"

So they quarreled among themselves, for they were beasts and knew no better; and as they snarled and growled and howled, the maiden walked in among them; and when the light which made her lovely fell upon them, they ran and hid themselves in the depths of the forest, and the child passed on in safety.

The rabbit still slept peacefully on her breast. At last she, too, grew weary, and lay down to sleep on the leaves and moss; and the birds of the forest watched her and sang to her, and nothing harmed her all the night.

In the morning a party of horsemen rode through the forest, looking behind each bush and tree as if they sought something very precious.

The forest glowed with splendor then, for the sun had come in all its glory to scatter darkness and wake up the world. The darkest dells and caves and lonely paths lost their horror in the morning light, and there were violets blooming in the shadows of the pines.

The leaves glistened, the flowers lifted their heads, and everything was glad but the horsemen, whose faces were full of gloom because their hearts were sad.

They did not speak or smile as they rode on their search; and their leader was the saddest of them all, though he wore a golden crown that sparkled with many jewels.

They followed each winding path through the forest, till at last they reached the spot where the little maiden lay.

The rabbit waked up at the sound of their coming, but the child slept till a loud cry of gladness awakened her and she found herself in her father's arms.

In the night-time the king's brave soldiers had driven his enemies from his land, and opened the doors of the prison-house in which he and the queen lay, and the king had ridden with them in haste to find his darling child, who was worth his crown and his kingdom.

The sight of her face was the sunshine to lighten their hearts, and they sent the glad news far and near, with blast of trumpet and shouts of joy.

But in all their great happiness the child did not forget the rabbit, and she said to it, "Come with me and I will take care of you, for my father the king is here." But the rabbit thanked her and wanted to go home.

"My babies are waiting," it said, "and I have my work to do in the world. I pray you let me go."

So the child kissed it and bade it go; and she, too, went to her own dear home. There she grew lovelier every day, for the light grew with her; and when, long years afterward, she was queen of the country, the foxes and wolves and tigers dared not harm her people, for her good knights drove evil from her land; but to loving gentle creatures she gave love and protection, and she lived happily all the days of her life.

There was once a man who owned a little gray pony.

Every morning when the dewdrops were still hanging on the pink clover in the meadows, and the birds were singing their morning song, the man would jump on his pony and ride away, clippety, clippety, clap!

The pony's four small hoofs played the jolliest tune on the smooth pike road, the pony's head was always high in the air, and the pony's two little ears were always pricked up; for he was a merry gray pony, and loved to go clippety, clippety, clap!

The man rode to town and to country, to church and to market, up hill and down hill; and one day he heard something fall with a clang on a stone in the road. Looking back, he saw a horseshoe lying there. And when he saw it, he cried out:—

Then down he jumped, in a great hurry, and looked at one of the pony's fore-feet; but nothing was wrong. He lifted the other forefoot, but the shoe was still there. He examined one of the hindfeet, and began to think that he was mistaken; but when he looked at the last foot, he cried again:—

Then he made haste to go to the blacksmith; and when he saw the smith, he called out to him:—

But the blacksmith answered and said:—

The man was downcast when he heard this; but he left his little gray pony in the blacksmith's care, while he hurried here and there to buy the coal.

First of all he went to the store; and when he got there, he said:—

But the storekeeper answered and said:—

Then the man went away sighing, and saying:—

By and by he met a farmer coming to town with a wagon full of good things; and he said:—

Then the farmer answered the man and said:—

So the farmer drove away and left the man standing in the road, sighing and saying:—

In the farmer's wagon, full of good things, he saw corn, which made him think of the mill; so he hastened there, and called to the dusty miller:—

The miller came to the door in surprise; and when he heard what was needed, he said:—

Then the man turned away sorrowfully and sat down on a rock near the roadside, sighing and saying:—

After a while a very old woman came down the road, driving a flock of geese to market; and when she came near the man, she stopped to ask him his trouble. He told her all about it; and when she had heard it all, she laughed till her geese joined in with a cackle; and she said:—

Then the man sprang to his feet, and, thanking the old woman, he ran to the miner. Now the miner had been working many a long day down in the mine, under the ground, where it was so dark that he had to wear a lamp on the front of his cap to light him at his work! He had plenty of black coal ready and gave great lumps of it to the man, who took them in haste to the blacksmith.

The blacksmith lighted his great red fire, and hammered out four fine new shoes, with a cling! and a clang! and fastened them on with a rap! and a tap! Then away rode the man on his little gray pony,—clippety, clippety, clap!

Once there was a very dear family,—Father, Mother, big Brother Tom, little Sister Polly, and the baby, who had a very long name, Gustavus Adolphus; and every one of the family wanted a home more than anything else in the world.

They lived in a house, of course, but that was rented; and they wanted a home of their very own, with a sunny room for Mother and Father and Baby, with a wee room close by for the little sister; a big, airy room for Brother Tom; a cosy room for the cooking and eating; and, best of all, a room that Grandmother might call her own when she came to see them.

A box which Tom had made always stood on Mother's mantel, and they called it the "Home Bank," because every penny that could be spared was dropped in there for the building of the home.

This box had been full once, and was emptied to buy a little piece of ground where the home could be built when the box was full again.

The box filled very slowly, though; and Gustavus Adolphus was nearly three years old when one day the father came in with a beaming face and called the family to him.

Mother left her baking, and Tom came in from his work; and after Polly had brought the baby, the father asked them very solemnly: "Now, what do we all want more than anything else in the world?"

"A home!" said Mother and Brother Tom.

"A home!" said little Sister Polly.

"Home!" said the baby, Gustavus Adolphus, because his mother had said it.

"Well," said the father, "I think we shall have our home if each one of us will help. I must go away to the great forest, where the trees grow so tall and fine. All Winter long I must chop the trees down, and in the Spring I shall be paid in lumber, which will help in the building of the home. While I am away, Mother will have to fill my place and her own too, for she will have to go to market, buy the coal, keep the pantry full, and pay the bills, as well as cook and wash and sew, take care of the children, and keep a brave heart till I come back again."

The mother was willing to do all this and more, too, for the dear home; and Brother Tom asked eagerly: "What can I do?—what can I do?" for he wanted to begin work right then, without waiting a moment.

"I have found you a place in the carpenter's shop where I work," answered the father. "And you will work for him, and all the while be learning to saw and hammer and plane, so that you will be ready in the Spring to help build the home."

Now, this pleased Tom so much that he threw his cap in the air and hurrahed, which made the baby laugh; but little Polly did not laugh, because she was afraid that she was too small to help. But after a while the father said: "I shall be away in the great forest cutting down the trees; Mother will be washing and sewing and baking; Tom will be at work in the carpenter's shop; and who will take care of the baby?"

"I will, I will!" cried Polly, running to kiss the baby. "And the baby can be good and sweet!"

So it was all arranged that they would have their dear little home, which would belong to every one, because each one would help; and the father made haste to prepare for the Winter. He stored away the firewood and put up the stoves; and when the wood-choppers went to the great forest, he was ready to go with them.

Out in the forest the trees were waiting. Nobody knew how many years they had waited there, growing every year stronger and more beautiful for the work they had to do. Every one of them had grown from a baby tree to a giant; and when the choppers came, there stood the giant trees, so bare and still in the wintry weather that the sound of the axes rang from one end of the woods to the other. From sunrise to sunset the men worked steadily; and although it was lonely in the woods when the snow lay white on the ground and the cold wind blew, the father kept his heart cheery. At night, when the men sat about the fire in their great log-house, he would tell them about the mother and children who were working with him for a home.

Nobody's ax was sharper than his or felled so many trees, and nobody was gladder when Spring-time came and the logs were hauled down to the river.

The river had been waiting too, through all the Winter, under its shield of ice, but now that Spring had come, and the snows were melting, and all the little mountain streams were tumbling down to help, the river grew very broad and strong, and dashed along, snatching the logs when the men pushed them in and carrying them on with a rush and a roar.

The men followed close along the bank of the river, to watch the logs and keep them moving; but at last there came a time when the logs would not move, but lay in a jam from shore to shore while the water foamed about them.

"Who will go out to break the jam?" said the men. They knew that only a brave man and a nimble man could go, for there was danger that the logs might crush him and the river sweep him away.

They looked at each other. But the father was not afraid, and he was surefooted and nimble; so he sprang out in a moment, with his ax, and began to cut away at the logs.

"Some of these logs may help to build a home," he said; and he found the very log that was holding the others tight, and as soon as that was loosened, the logs began to move.

"Jump! Jump!" cried the men, as they ran for their lives; and, just as the logs dashed on, with a rumble and a jumble and a jar that sent some of the logs flying up in the air, the father reached the bank safely.

The hard work was over now. After the logs had rested in the log "boom," they went on their way to the saw mills, where they were sawed into lumber to build houses; and then the father hurried home.

When he came there, he found that the mother had baked and washed and sewed and taken care of the children, as only such a precious mother could have done. Brother Tom had worked so well in the carpenter's shop, that he knew how to hammer and plane and saw, and had grown as tall and as stout as a young pine tree. Sister Polly had taken such care of the baby, that he looked as sweet and clean and happy as a rose in a garden; and the baby had been so good, that he was a joy to the whole family.

"I must get this dear family into their home," said the father; and he and Brother Tom went to work with a will. And the home was built, with a sunny room for Father and Mother and Baby, a wee little room close by for good Sister Polly, a big airy room for big Brother Tom, a cosy room for the cooking and eating, and best of all, a room for the dear grandmother, who came then to live with them all the time.

Once upon a time there was a little boy who had a long journey to go. He had a very dear mother, and she did not want her little son to leave her; but she knew he must go, so she put her arms around him and said: "Now, don't be afraid, for I shall be thinking of you, and God will take care of you."

Then the little boy kissed her goodbye and ran away, singing a merry song. As long as he could see her he would turn and wave his hand to her; but by and by she was out of sight. Just then he came to a stream of water that ran across his path.

"How can I get over?" thought the little boy; but a white swan swam up to greet him, and said:—

"There is always a way to get over the stream. Follow me! follow me!"

So the little boy followed the swan till he came to a row of great stepping stones, and he jumped from one to another, counting them as he went.

When he reached the seventh he was safe across, and he turned to thank the white swan. And when he had thanked her, he called:—

Then the white swan swam back to carry the message, and the little boy ran on his way.

Oh! there were so many beautiful things to hear,—the birds singing and the bees humming; and so many beautiful things to see,—the flowers and butterflies and green grass! And after a while he came to a wood, where every tree wore a green dress; and through the wood, under the shade of the trees, flowed a babbling creek.

"I wonder how I can get over?" said the little boy; and the wise wind whispered:

"There is always a way to get over the stream. Follow me! follow me!"

Then he followed the sound of the wise wind's voice, and the wind blew against a tall pine tree, and the pine tree fell across the creek, and lay there, a great round foot-log, where the little boy might step. He made his way over, and thanked the wise wind; and he asked:—

The wind blew back to carry the message, and the little boy made haste on his journey. His way lead through a meadow, where the clover grew and the white sheep and baby lambs were feeding together in the sunshine.

On one side of this meadow flowed a silver shining river, and the child wandered up and down the bank to find some way to cross, for he knew that he must go on.

As he walked there, a man called a carpenter found him, and said to him:—

"There is always a way to get over the stream. Follow me! follow me!"

Then the little boy followed the carpenter, and the carpenter and his men built a bridge of iron and wood that reached across from bank to bank. And when the bridge was finished, the child ran over in safety; and after he had thanked the carpenter, he said:—

The carpenter gladly consented; and after he had turned back to carry the message, the little boy followed the path, which led up hill over rocks and steep places, through brambles and briars, until his feet grew weary; and when he came down into the valley again, he saw a river that was very dark and very deep.

There was no white swan or wise wind to help him. No tree in the forest could bridge it over, and the carpenter and his men were far away.

"I must get over. There is a way," said the little boy bravely; and, as he sat down to rest, he heard a murmuring sound. Looking down, he spied a tiny boat fastened to a willow tree.

repeated the boat; and when the little boy had unfastened it, he sprang in, and began to row himself over the dark water.

As he rowed, he saw a tiny bird flying above him. The bird needed no boat or bridge, for its wings were strong; and when the little boy saw it, he cried:—

The little bird flew swiftly back to carry the message, and the boy rowed on till he reached the opposite shore. After he had thanked the boat with its helping oar, he tied it to a tree as he had found it, and then hastened away, singing his happy song again.

By and by he heard an answer to his song, and he knew that it was the great sea, calling "Come! Come! Come!" And when he reached the shore where the blue waves were dancing up to the yellow sands, he clapped his hands with delight; for there, rocking on the billows, was a beautiful ship with sails as white as a lady's hands.

"I knew there would be a way!" said the little boy, as he sprang on deck and went sailing over the deep blue sea,—sailing, sailing, sailing, day after day, night after night, over the beautiful sea.

At night the stars would look down, twinkling and blinking; and as the little boy watched them, he would say:—

The little boy went on sailing, sailing, day and night, until he came to a land beyond the sea,—a land so full of delight that the little boy felt that his journey was ended, until one day when a great storm came.

The wind blew, the thunder crashed, the lightning flashed, the rain came pouring down, and the little boy wanted to go home.

"I will find a way!" he cried at last; and, just as he spoke, the sun came bursting out, the storm clouds rolled away, and there in the sky was a rainbow bridge that seemed to touch both sky and earth.

Then the little boy's heart leaped for joy, and he ran with feet as light as feathers up the shining bow; and when he reached the highest arch, he looked down on the other side and saw home and his mother at the rainbow's end.

"Mother! Mother!" he called, as he ran down into her arms. "Mother, I've always been thinking of you, and God has taken care of me."

One bright summer afternoon, Fleet, the good old shepherd dog that helped to take care of the farmyard, decided that he would step into the barn to see his friend Mrs. Muffet and her two little kittens, for he had not been able to chat with them for some time.

On his way, Fleet looked around to see that all was right. The weather was warm and the hens were taking a dust bath under the apple tree, and the brindle calf was asleep in the shadow of the barn. The ducks and geese were at the pond, the horses were at work in a distant field, the cows and sheep were in pasture, and only the brown colt kicked up his heels in the farmyard; so Fleet barked with satisfaction, and walked into the barn.

Inside he found Mrs. Muffet washing her face, while her two little kittens slept in the hay; and she gave Fleet a warm welcome.

"Good evening, Mrs. Muffet," said he.

"Good evening, Friend Fleet," answered she.

"How are the children?" asked the good dog, "and do they grow?"

"Grow?" said Mrs. Muffet. "You never saw anything like them! and such tricks as they play! Tittleback is the merrier, and will play with his own tail when he can find nothing else; but Toddlekins can climb in a way that is astonishing. Why, he even talks of going to the top of the barn, and no doubt he will, some day."

"No doubt, no doubt," said Fleet. "Children are so remarkable now."

"But what is the news with you, Friend Fleet?" inquired Mrs. Muffet.

"Nothing at all," said Fleet. "The barnyard is as quiet"—but just as he spoke there arose such a clatter outside the door that he sprang to his feet to see what was the matter, and the two kittens waked up in alarm. Outside, the yard was in a commotion. Everybody was talking at the same time. The hens were cackling, the roosters crowing, the ducks quacking, the calf crying, and the sound of flying hoofs could be heard far down the road.

"Pray, what is the matter?" said Fleet to three geese, that were hurrying along, with their necks stretched out.

"The gate is open, the brown colt's gone, the brindle calf's going and we are thinking about it; quawk! quawk!" said the three geese, Mrs. Waddle, Mrs. Gabble, and Mrs. Dabble.

"Where are you going?" asked Mrs. Muffet, putting her head out of the barn door.

"Out into the world," said the three geese together.

"You'd better go back to your pond," barked Fleet, as he bounded off to help the cook, who was waving her apron to keep back the brindle calf, while the milkmaid shut the gate, and little Dick ran down the road after the brown colt.

The brown colt kicked up his heels, and did not care how fast Dick ran. He had all the world to roam in, and the green grass was growing everywhere; so he tossed his head and galloped away toward the blue hills.

After a while he looked to see whether Dick was still following him, but nobody was in sight; so he lay down and rolled over among the daisies; and this was such fun that he tried it again, and again, until he was tired.

Then he nibbled the grass awhile, but soon decided to take another run; and he raised such a dust, as he scampered along, that the birds peeped down from the trees to see what it was, and a little rabbit that ran across the road was so astonished that it did not take breath again till it reached its greenwood home.

"Hurrah!" said the brown colt, not because he knew what it meant but because he had heard Dick say it. "Hurrah! maybe I'll never go back!"

Just then there came an awful screech out of a neighboring field, and, although it was only the whistle of a threshing machine, the brown colt was terribly frightened, and jumped over a fence into a cotton field.

"Oh!" thought he, as he tore his glossy coat on the sharp barbs of the wire fence and cut his feet as he leaped awkwardly over, "Oh! how I wish I could see Dick now."

But Dick was at home. He had run after the brown colt as fast as his feet could carry him, and had called "Whoa! Whoa!" but the brown colt would not listen; so Dick had gone home with his head hanging down, for he was the very one who had forgotten to shut the farmyard gate.

Mother was at home, and she felt very sorry when she heard about it, for she knew how dear that colt was to her careless little boy; and when father came in from the fields, too late to look for the runaway, he said that big boys and little boys and everybody else must take care of the things they wanted to keep; and Dick cried, but it did no good.

The cows came home when father did, and the brindle calf was glad that she had not gone away from the farmyard when she saw her mother come in from the clover lot. The chickens went to roost, and the horses were fed; but no brown colt came in sight, although Dick and Fleet went down the lane to look, a dozen times.

"He's sorry enough," said Friend Fleet to Mrs. Muffet, as they ate their supper; and Mrs. Muffet told Tittleback and Toddlekins all about it, when she went back to the barn.

Poor little Dick! and poor brown colt! They thought about each other very often that night; and early in the morning the man who owned the cotton field, drove the brown colt out.

"I'd like to know," said the man, as he hurried him along, "what business you have in my cotton field!" But the brown colt hung his head, as Dick had done, and limped away.

The long pike road stretched out, hard and white, before him, and the birds, chattering in the bushes, seemed to say:—

"Is this the same brown colt that raised such a dust yesterday?"

Oh! how long and weary the way was, to his limping feet! But at last he reached home, just at milking time; and when the milkmaid saw him standing at the gate, she gave a scream that brought the household out.

Dick and the cook and Fleet tumbled over each other in their surprise, and the barnyard was in such an excitement that one hen lost her chickens and did not find them all for fifteen minutes.

"What did you see?" cried the brindle calf.

"What made you come back?" asked the geese; but Dick and Friend Fleet asked no questions, because they understood.

That was a long time ago, and the brown colt is a strong horse now, and Dick a tall boy; but neither of them will ever forget the day when Dick was careless and did not shut the farmyard gate.

Grandmother's garden was a beautiful place,—more beautiful than all the shop windows in the city; for there was a flower or grass for every color in the rainbow, with great white lilies, standing up so straight and tall, to remind you that a whole rainbow of light was needed to make them so pure and white.

There were pinks and marigolds and princes' feathers, with bachelor's buttons and Johnny-jump-ups to keep them company. There were gay poppies and gaudy tulips, and large important peonies and fine Duchess roses in pink satin dresses.

There were soft velvet pansies and tall blue flags, and broad ribbon-grasses that the fairies might have used for sashes; and mint and thyme and balm and rosemary everywhere, to make the garden sweet; so it was no wonder that every year, the garden was full of visitors.

Nobody noticed these visitors but Grandmother and Lindsay.

Lindsay was a very small boy, and Grandmother was a very old lady; but they loved the same things, and always watched for these little visitors, who came in the early spring-time and stayed all summer with Grandmother.

Early, early in the spring, when the garden was bursting into bloom in the warm southern sunshine, Grandmother and Lindsay would sit in the arbor, where the vines crept over and over in a tangle of bloom, and listen to a serenade. Music, music everywhere! Over their heads, behind their backs, the little brown bees would fly, singing their song:—

while they found the golden honey cups, and filled their pockets with honey to store away in their waxen boxes at home.

One day, while Grandmother and Lindsay were watching, a little brown bee flew away with his treasure, and lighting on a rose, met with a cousin, a lovely yellow butterfly.

"I think they must be talking to each other," said Grandmother, softly. "They are cousins, because they belong to the great insect family, just as your papa and Uncle Bob and Aunt Emma and Cousin Rachel all belong to one family,—the Greys; and I think they must be talking about the honey that they both love so well."

"I wish I could talk to a butterfly," said Lindsay, longingly; and Grandmother laughed.

"Play that I am a butterfly," she proposed. "What color shall I be?—a great yellow butterfly, with brown spots on my wings?"

So Grandmother played that she was a great yellow butterfly with brown spots on its wings, and she said to Lindsay:—

"Never in the world can you tell, little boy, what I used to be?"

"A baby butterfly," guessed Lindsay.

"Guess again," said the butterfly.

"A flower, perhaps; for you are so lovely," declared Lindsay, gallantly.

"No, indeed!" answered the butterfly; "I was a creeping, crawling caterpillar."

"Now, Grandmother, you're joking!" cried Lindsay, forgetting that Grandmother was a butterfly.

"Not I," said the butterfly. "I was a crawling, creeping caterpillar, and I fed on leaves in your Grandmother's garden until I got ready to spin my nest; and then I wrapped myself up so well that you would never have known me for a caterpillar; and when I came out in the Spring I was a lovely butterfly."

"How beautiful!" said Lindsay. "Grandmother, let us count the butterflies in your garden." But they never could do that, though they saw brown and blue and red and white and yellow ones, and followed them everywhere.

It might have been the very next day that Grandmother took her knitting to the summer house. At all events it was very soon; and while she and Lindsay were wondering when the red rose bush would be in full bloom, Lindsay saw, close up to the roof, a queer little house, like a roll of crumpled paper, with a great many front doors; and, of course, he wanted to know who lived there.

"You must not knock at any of those front doors," advised Grandmother, "because Mrs. Wasp lives there, and might not understand; although if you let her alone she will not hurt you. Just let me tell you something about her."

So Lindsay listened while Grandmother told the story:—

Once there was a little elf, who lived in the heart of a bright red rose, just like the roses we have been talking about.

There were many other elves who lived in the garden. One, who lived in a lily which made a lovely home; and a poppy elf, who was always sleepy; but the rose elf liked her own sweet smelling room, with its crimson curtains, best of all.

Now the rose elf had a very dear friend, a little girl named Polly. She could not speak to her, for fairies can only talk to people like you and me in dreams and fancies, but she loved Polly very much, and would lie in her beautiful rose room, and listen to Polly's singing, till her heart was glad.

One day as she listened she said to herself, "If I cannot speak to Polly, I can write her a letter;" and this pleased her so much that she called over to the lily elf to ask what she should write it on. "I always write my letters on rose petals, and get the wind to take them," said the rose elf. "But I am afraid Polly would not understand that."

"I will tell you," answered the lily elf, "what I would do. I would go right to Mrs. Wasp, and ask her to give me a piece of paper."

"But Mrs. Wasp is very cross, I've heard," said the rose elf timidly.

"Never believe the gossip that you hear. If Mrs. Wasp does seem to be a little stingy, I'm sure she has a good heart," replied the lily elf. So the rose elf took courage, and flew to Mrs. Wasp's house, where, by good fortune, she found Mrs. Wasp at home.

"Good morning Mrs. Wasp," called the little elf, "I've come to see if you will kindly let me have a sheet of paper to-day."

"Now," said the wasp, "I have just papered my house with the last bit of paper I had, but if you can wait, I will make you a sheet."

Then the rose elf knew that Mrs. Wasp had a kind heart; and she waited and watched with a great deal of interest while Mrs. Wasp set to work. Now, close by her house was an old bit of dry wood, and Mrs. Wasp sawed it into fine bits, like thread, with her two sharp saws that she carries about her. Then she wet these bits well with some glue from her mouth, and rolled them into a round ball.

"Oh, Mrs. Wasp!" cried the rose elf, "I'm afraid I am putting you to too much trouble."

"Don't fret about me," said the wasp; "I'm used to work." So she spread out the ball, working with all her might, into a thin sheet of gray paper; and when it was dry, she gave it to the rose elf.

"Thank you, good Mrs. Wasp," said the elf; and she flew away to invite the lily elf and the poppy elf to help her with the letter, for she wanted it to be as sweet as all the flowers of spring.

When it was finished they read it aloud.

The letter was sent by a bluebird; and the elf was sure that Polly understood, for that very day she came and stood among the flowers to sing the very sweetest song she knew.

Out in Grandmother's garden, just as the sun was up, a very cunning spinner spun a lovely wheel of fine beautiful threads; and when Grandmother and Lindsay came out, they spied it fastened up in a rose bush.

The small, cunning spinner was climbing a silken rope near by with her eight nimble legs, and looking out at the world with her eight tiny eyes, when Grandmother saw her and pointed her out to Lindsay; and Lindsay said:—

"Oh, Mrs. Spider! come spin me some lace!" which made Grandmother think of a little story which she had told Lindsay's papa and all of her little children, when they were lads and lassies, and this garden of hers had just begun to bloom.

She sat down on the steps and told it to Lindsay.

Once, long, long ago, when the silver moon was shining up in the sky, and the small golden stars were twinkling, twinkling, a little fairy with a bundle of dreams went hurrying home to fairyland.

She looked up at the stars and moon to see what time it was, for the fairy queen had bidden her come back before the day dawned.

All out in the world it was sleepy time; and the night wind was singing an old sweet lullaby, and the mocking bird was singing too, by himself, in the wood.

"I shall not be late," said the fairy, as she flew like thistle-down through the air or tripped over the heads of the flowers; but in her haste she flew into a spider's web, which held her so fast that, although she struggled again and again, she could not get free.

Her bundle of dreams fell out of her arms, and lay on the ground under the rose-bush; and the poor little fairy burst into tears, for she knew that daylight always spoiled dreams, and these were very lovely ones.

Her shining wings were tangled in the web, her hands were chained, and her feet were helpless; so she had to lie still and wait for the day time which, after all, came too soon.

As soon as the sun was up, Mrs. Spider came out of her den; and when she saw the fairy she was very glad, for she thought she had caught a new kind of fly.

"If you please, Mrs. Spider," cried the fairy quickly, "I am only a little fairy, and flew into your web last night on my way home to fairyland."

"A fairy!" said Mrs. Spider crossly, for she was disappointed; "I suppose you are the one who helps the flies to get away from me. You see well enough then!"

"I help them because they are in trouble," answered the fairy gently.

"So are you, now," snapped the spider, "But the flies won't help you."

"But perhaps you will," pleaded the fairy.

"Perhaps I won't," said the spider, going back into her house and leaving the little fairy, who felt very sorrowful.

Her tears fell like dew drops on the spider web, and the sun shone on them, and made them as bright as the fairy queen's diamonds.

The fairy began to think of the queen and the court, and the bundle of dreams; and she wondered who would do the work if she never got free. The fairy queen had always trusted her, and had sent her on many errands.

Once she had been sent to free a mocking-bird that had been shut in a cage. She remembered how he sang in his cage, although he was longing for his green tree tops.

She smiled through her tears when she thought of this, and said to herself:—

"I can be singing, too! It is better than crying."

Then she began to sing one of her fairy songs:—

Now though the fairy did not know it, Mrs. Spider was very fond of music; and when she heard the sweet song, she came out to listen. The little fairy did not see her, so she sang on:—

Mrs. Spider came a little farther out, while the fairy sang:—

Just as the fairy finished the song she looked up, and there was Mrs. Spider, who had come out in a hurry.

"The flies are not going to help you," said she, "so I will;" and she showed the fairy how to break the slender threads, until she was untangled and could fly away through the sunshine.

"What can I do for you, dear Mrs. Spider?" the fairy asked, as she picked up her bundle of dreams.

"Sing me a song sometimes," replied Mrs. Spider. But the fairy did more than that; for soon after she reached fairyland, the fairy queen needed some fine lace to wear on her dress at a grand ball.

"Fly into the world," she said, "and find me a spinner; and tell her that when she has spun the lace, she may come to the ball and sit at the queen's table."

As soon as the fairy heard this, she thought of the spider, and made haste to find her and tell her the queen's message.

"Will there be music?" asked the spider.

"The sweetest ever heard" answered the fairy; and the spider began to spin.

The lace was so lovely when it was finished, that the fairy queen made the spider court spinner; and then the spider heard the fairies sing every day, and she too had love in her heart.

A mocking bird sang in Grandmother's garden. He was king of the garden, and the rose was queen. Every night when the garden was still, he serenaded Grandmother; and she would lie awake and listen to him, for she said he told her all the glad tidings of the day, and helped her understand the flower folk and bird folk and insect folk that lived in her garden.

Lindsay always thought the mocking bird told Grandmother the wonderful stories she knew, and he wanted to hear them, too, late in the night time; but he never could keep awake. So he had to be contented with the mocking bird in the morning, when he was so saucy.

There were orioles and thrushes and bluebirds, big chattering jays, sleek brown sparrows, and red-capped woodpeckers; but not a bird in the garden was so gay and sweet and loving as the mocking bird, who could sing everybody's song and his own song, too.

Night after night he sang his own song in Grandmother's garden. But there came a night when he did not sing; and though Grandmother and Lindsay listened all next day, and looked in every tree for him, he could not be found.

"I'm afraid somebody has caught him and shut him up in a cage" said Grandmother; and when Lindsay heard this he was very miserable; for he knew that somewhere in the garden, there was a nest and a mother bird waiting.

He and Grandmother talked until bed-time about it, and early next morning Lindsay asked Grandmother to let him go to look for the bird.

"Please do, Grandmother," he begged. "If somebody has him in a cage I shall be sure to find him; and I will take my own silver quarter to buy him back."

So after breakfast Grandmother kissed him and let him go, and he ran down the path and out of the garden gate, and asked at every house on the street:—

"Is there a mocking bird in a cage here?"

This made people laugh, but Lindsay did not care. By and by, he came to a little house with green blinds; and the little lady who came to the door did not laugh at all when she answered his question:—

"No; there are no mocking birds here; but there are two sweet yellow canaries. Won't you come in to see them?"

"I will sometime, thank you, if Grandmother will let me," said Lindsay; "but not to-day; for if that mocking bird is in a cage, I know he's in a hurry to get out."

Then he hurried on to the next house, and the next; but no mocking birds were to be found. After he had walked a long way, he began to be afraid that he should have to go home, when, right before him, in the window of a little house, he saw a wooden box with slats across the side; and in the box was a very miserable mocking bird!

"Hurrah! hurrah!" cried Lindsay, as he ran up the steps and knocked at the door. A great big boy came to the window and put his head out to see what was wanted.

"Please, please," said Lindsay, dancing up and down on the doorstep, "I've come to buy the mocking-bird; and I've a whole silver quarter to give for it, because I think maybe he is the very one that sang in Grandmother's garden."

"I don't want to sell it," answered the boy, with a frown on his face.

Lindsay had never thought of anything like this, and his face grew grave; but he went bravely on:—-

"Oh! but you will sell it, maybe. Won't you, please? Because I just know it wants to get out. You wouldn't like to be in a cage yourself, you know, if you had been living in a garden,—'specially my Grandmother's."

"This bird ain't for sale," repeated the boy, crossly, frowning still more over the bird-cage.

"But God didn't make mocking-birds for cages," cried Lindsay, choking a little. "So it really isn't yours."

"I'd like to know why it isn't," said the boy. "You'd better get off my doorstep and go home to your Granny, for I'm not going to sell my mocking-bird,—not one bit of it;" and he drew his head back from the window and left Lindsay out on the doorstep.

Poor little Lindsay! He was not certain that it was the bird, but he was sure that mocking-birds were not meant for cages; and he put the quarter back in his pocket and took out his handkerchief to wipe away the tears that would fall.

All the way home he thought of it and sobbed to himself, and he walked through the garden gate almost into Grandmother's arms before he saw her, and burst into tears when she spoke to him.

"Poor little boy!" said Grandmother, when she had heard all about it; "and poor big boy, who didn't know how to be kind! Perhaps the mocking-bird will help him, and, after all, it will be for the best."

Grandmother was almost crying herself, when a click at the gate made them both start and, then look at each other; for there, coming up the walk, was a great big boy with a torn straw hat, and with a small wooden box in his hand, which made Lindsay scream with delight, for in that box was a very miserable-looking mocking-bird.

"Guess it is yours," said the boy, holding the box in front of him, "for I trapped it out in the road back of here. I never thought of mocking-birds being so much account, and I hated to make him cry."

"There now," cried Lindsay, jumping up to get the silver quarter out of his pocket. "He is just like Mrs. Wasp, isn't he, Grandmother?" But the boy had gone down the walk and over the gate without waiting for anything, although Lindsay ran after him and called.

Lindsay and Grandmother were so excited that they did not know what to do. They looked out of the gate after the boy, then at each other, and then at the bird.

Lindsay ran to get the hatchet, but he was so excited with joy that he could not use it, so Grandmother had to pry up the slats, one by one; and every time one was lifted, Lindsay would jump up and down and clap his hands, and say, "Oh, Grandmother!"

At last, the very last slat was raised; and then, in a moment, the mocking bird flew up, up, up into the maple tree, and Lindsay and Grandmother kissed each other for joy.

Oh! everything was glad in the garden. The breezes played pranks, and blew the syringa petals to the ground, and up in the tallest trees the birds had a concert. Orioles, bluebirds, and thrushes, chattering jays, sleek brown sparrows, and red-capped woodpeckers, were all of them singing for Grandmother and Lindsay; but the sweetest singer was the mocking bird who was singing everybody's sweet song, and then his own, which was the sweetest of all.

"I know he is glad," Lindsay said to Grandmother; "for it is, oh, so beautiful to live inside your garden gate!"

A little boy, named Joseph, went with his papa, once upon a time, to visit his Grandma. Grandma was an old, old lady, with hair as white as drifted snow; and she petted Joseph's papa almost as much as she did Joseph, for Papa had been her baby long, long before.

It was a fine thing to go to see Grandma; and Joseph would have been willing to stay a long time, if it had not been that Mamma and the baby and big brother were at home.

He knew they needed him there, too, for Mamma wrote it in a letter.

"Dear Papa," she said, in the letter that the stage coach brought, "When are you, and my precious Joseph coming home? The baby and Brother and I are well but we want to see you. We need a little boy here who can hunt hens' nests and feed chickens, and rock the baby's cradle. Please bring one home with you."

This made Joseph laugh for, of course, Mamma meant him; and though he forgot some of her letter, he always remembered that; and when Papa said; "Look here, Joseph, we must go home," he was just as glad to go, as he had been to come to see Grandma.

Now Joseph and his papa had to travel by stage coach, because there were no trains in those days; and after they had told Grandma goodbye, on the morning they left, they went down to the inn to wait for the stage.

The inn was the place where travelers who were away from home might stop and rest, and the landlady tried to be always pleasant and make everybody feel at home; so she hurried out on the porch, with two chairs for Joseph and his papa, as soon as she saw them.

They were a little early for the stage, so Joseph sat and watched the wagons and carriages, that passed the inn. All the carriages had ladies and children inside, and Joseph thought they must be going to see their grandmas.

Most of the wagons that passed the inn were loaded down. Some of them were full of hay; and Joseph knew in a minute, where they were going, for he had heard his Grandma say that she was going to store her hay away in a barn, that very day.

Some of the wagons carried good things to sell; and the men who drove them would ring their bells, and call out, now and then: "Apples to sell! Apples to sell!" or "Potatoes and corn! Potatoes and corn!" which made Joseph laugh.

Then there was the milkman. His tin cans were so bright that you could see yourself in them, and Joseph knew that they carried good sweet milk.

This made him think of their own cows. He could shut his eyes and see how each one looked. Clover was red, Teenie black, and Buttercup had white spots on her back.

Just then he heard the sound of a horn; and his father jumped up in a hurry and collected their bundles. "For," said he, "that is the guard blowing his horn, and the stage coach is coming!"

Joseph was so pleased when he heard this that he jumped up and down; and while he was jumping, the stage coach whirled around the corner.

There were four horses hitched to it, two white, and two black; and they were trotting along at a fine pace. The driver was a jolly good fellow, who sat on the top of the coach and cracked his whip; and the guard sat behind with the horn.

The wheels were turning so fast that you could scarcely see them, but as soon as the inn was reached, the horses stopped and the stage coach stood still. The guard jumped down to open the door, and Joseph and his papa made haste to get in. The guard blew his horn, the driver cracked his whip, the horses dashed off, and away went Joseph and his papa.

The stage coach had windows, and Joseph looked out. At first, all he could see was smooth, level ground; but after a while, the horses walked slowly and you could have counted the spokes in the wheels, for they were going up hill and the driver was careful of his horses.

The hill was so much higher than therest of the country that when Joseph looked out at the houses in the valley he felt very great, although it was only the hill that was high, after all.

Then they all came down on the other side, and the horses trotted faster. It was early in the morning, and the sunshine was so bright and the air so fresh that the horses tossed their heads, and their hoofs rang out as they hurried over the hard road.

The road ran through the wood, and Joseph could see the maples with their wide-spreading branches, and the poplar with its arms held up to the sky, and the birches with their white dresses, all nodding in the wind, as though they said, "How do you do?" Once, too, he saw a little squirrel running about, and once a queer rabbit.

Then the stage-coach stopped with a jerk.

"What's the matter?" called Joseph's papa, as the driver and the guard got down.

"The linch-pin has fallen out," answered the driver, "and we have just missed losing a wheel."

"Can we go on?" Joseph asked. And when his papa said "No," he felt sorry. But the guard said that he would go after a wheelwright who lived not far beyond; and Joseph and his papa walked about until the wheelwright came running, with his tools in his hand.

He set to work, and Joseph thought it was very funny that the great wheel could not stay on without the linch-pin; but the wheelwright said that the smallest screws counted. He put the wheel quickly in order, and off the stage-coach went.

The wheels whirled around all the more merrily because of the wheelwright's work; and when the hoofs of the horses clattered on the road, Joseph's papa said that the horse-shoes were saying:—

"It is the little shoes, the little shoes, that help the horse to go!"

Then Joseph looked down at his own small shoes and thought of his mother's letter, and the little boy that she needed to hunt eggs and feed chickens and rock the baby's cradle; and he was anxious to get home.

Clip, clap! clip, clap! The horses stepped on a bridge, and Joseph looked out to see the water. The bridge was strong and good, with great wooden piers set out in the water and a stout wooden railing to make it safe.

The sun was high and shining very brightly on the water, and little Joseph began to nod. He rested his head on papa's arm, and his eyelids dropped down over his two sleepy eyes, and he went so fast asleep that his papa was obliged to give him a little shake when he wanted to wake him up.

"Wake up, Joseph! wake up!" he cried, "and look out of the window!"

Joseph rubbed his eyes and looked out of the window; and he saw a red cow, a black cow, and a cow with spots on her back; and a little further on, a big boy and a baby; and, what do you think?—yes, a mamma! Then the stage-coach could not hold him or his papa another minute, because they were at home!

Long, long ago, when there were giants to be seen, as they might be seen now if we only looked in the right place, there lived a young giant who was very strong and very willing, but who found it hard to get work to do.

The name of the giant was Energy, and he was so great and clumsy that people were afraid to trust their work to him.

If he were asked to put a bell in the church steeple, he would knock the steeple down, before he finished the work. If he were sent to reach a broken weather vane, he would tear off part of the roof in his zeal. So, at last, people would not employ him and he went away to the mountains to sleep; but he could not rest, even though other giants were sleeping as still as great rocks under the shade of the trees.

Young Giant Energy could not sleep, for he was too anxious to help in the world's work; and he went down into the valley, and begged so piteously for something to do that a good woman gave him a basket of china to carry home for her.

"This is child's play for me," said the giant as he set the basket down at the woman's house, but he set it down so hard that every bit of the china was broken.

"I wish a child had brought it for me," answered the woman, and the young giant went away sorrowful. He climbed the mountain and lay down to rest; but he could not stay there and do nothing, so he went back to the valley to look for work.

There he met the good woman. She had forgiven him for breaking her china, and had made up her mind to trust him again; so she gave him a pitcher of milk to carry home.

"Be quick in bringing it," she said, "lest it sour on the way."

The giant took the pitcher and made haste to run to the house; and he ran so fast that the milk was spilled and not a drop was left when he reached the good woman's house.

The good woman was sorry to see this, although she did not scold; and the giant went back to his mountain with a heavy heart.

Soon, however, he was back again, asking at every house:—

"Isn't there something for me to do?" and again he met the good woman, who was here, there and everywhere, carrying soup to the sick and food to the hungry.

When she met the young Giant Energy, her heart was full of love for him; and she told him to make haste to her house and fill her tubs with water, for the next day was wash day.

Then the giant made haste with mighty strides towards the good woman's house, where he found her great tubs; and, lifting them with ease, he carried them to the cistern and began to pump.

He pumped with such force and with so much delight, that the tubs were soon filled so full that they ran over, and when the good woman came home she found her yard as well as her tubs full of water.

The young giant had such a downcast look, that the good woman could not be angry with him; she only felt sorry for him.

"Go to the Fairy Skill, and learn," said the good woman, as she sat on the doorstep. "She will teach you, and you will be a help in the world after all."

"Oh! how can I go?" cried the giant, giving a jump that sent him up over the tree tops, where he could see the little birds in their nests.

"Don't go so fast," said the good woman. "Stand still and listen! Go through the meadow, and count a hundred daffodils; then turn to your right, and walk until you find a mullein stalk that is bent. Notice the way it bends, and walk in that direction till you see a willow tree. Behind this willow runs a little stream. Cross the water by the way of the shining pebbles, and when you hear a strange bird singing you can see the fairy palace and the workroom where the Fairy Skill teaches her school. Go to her with my love and she will receive you."

The young giant thanked the good woman, stepped over the meadow fence, and counted the daffodils, "One, two, three," until he had counted a hundred. Then he turned to the right, and walked through the long grass to the bent mullein stalk, which pointed to the right; and after he had found the brook and crossed by way of the shining pebbles, he heard a strange bird singing, and saw among the trees the fairy palace.

He never could tell how it looked; but he thought it was made of sunshine, with the glimmer of green leaves reflected on it, and that it had the blue sky for a roof.

That was the palace; and at one side of it was the workshop, built of strong pines and oaks; and the giant heard the hum of wheels, and the noise of the fairy looms, where the fairies wove carpets of rainbow threads.

When the giant came to the door, the doorway stretched itself for him to pass through. He found Fairy Skill standing in the midst of the workers; and when he had given her the good woman's love, she received him kindly. Then she set him to work, bidding him sort a heap of tangled threads that lay in a corner like a great bunch of bright-colored flowers.

This was hard work for the giant's clumsy fingers, but he was very patient about it. The threads would break, and he got some of them into knots; but when Fairy Skill saw his work, she said:—

"Very good for to-day;" and touching the threads with her wand, she changed them into a tangled heap again. The next day the giant tried again, and after that again, until every thread lay unbroken and untangled.

Then Fairy Skill said "Well done," and led him to a loom and showed him how to weave.

This was harder work than the other had been; but Giant Energy was patient, although many times before his strip of carpet was woven the fairy touched it with her wand, and he had to begin over.

At last it was finished, and the giant thought it was the most beautiful carpet in the world.

Fairy Skill took him next to the potter's wheel, where cups and saucers were made out of clay; and the giant learned to be steady, to shape the cup as the wheel whirled round, and to take heed of his thumb, lest it slip.

The cups and saucers that were broken before he could make beautiful ones would have been enough to set the queen's tea table!

Fairy Skill then took him to the gold-smith, and there he was taught to make chains and bracelets and necklaces; and after he had learned all these things, the fairy told him that she had three trials for him. Three pieces of work he must do; and if he did them well, he could go again into the world, for he would then be ready to be a helper there.

"The first task is to make a carpet," said Fairy Skill, "a carpet fit for a palace floor."

Giant Energy sprang to his loom, and made his silver shuttle glance under and over, under and over, weaving a most beautiful pattern.

As he wove, he thought of the way by which he had come; and his carpet became as green as the meadow grass, and lovely daffodils grew on it. When it was finished, it was almost as beautiful as a meadow full of flowers!

Then the fairy said that he must turn a cup fine enough for a king to use. And the giant made a cup in the shape of a flower; and when it was finished, he painted birds upon it with wings of gold. When she saw it, the fairy cried out with delight.

"One more trial before you go," she said. "Make me a chain that a queen might be glad to wear."

So Giant Energy worked by day and by night and made a chain of golden links; and in every link was a pearl as white as the shining pebbles in the brook. A queen might well have been proud to wear this chain.

After he had finished, Fairy Skill kissed him and blessed him, and sent him away to be a helper in the world, and she made him take with him the beautiful things which he had made, so that he might give them to the one he loved best.

The young giant crossed the brook, passed the willow, found the mullein stalk, and counted the daffodils.

When he had counted a hundred, he stepped over the meadow fence and came to the good woman's house.

The good woman was at home, so he went in at the door and spread the carpet on the floor, and the floor looked like the floor of a palace.

He set the cup on the table, and the table looked like the table of a king; and he hung the chain around the good woman's neck, and she was more beautiful than a queen.

And this is the way that young Giant Energy learned to be a helper in the world.

Long, long ago there lived, in a kingdom far away, five knights who were so good and so wise that each one was known by a name that meant something beautiful.

The first knight was called Sir Brian the Brave. He had killed the great lion that came out of the forest to frighten the women and children, had slain a dragon, and had saved a princess from a burning castle; for he was afraid of nothing under the sun.

The second knight was Gerald the Glad, who was so happy himself that he made everybody around him happy too; for his sweet smile and cheery words were so comforting that none could be sad or cross or angry when he was near.