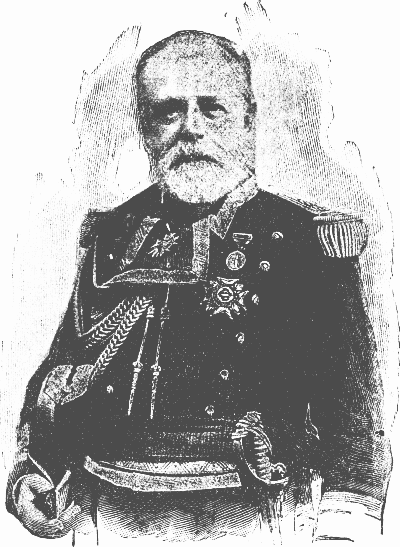

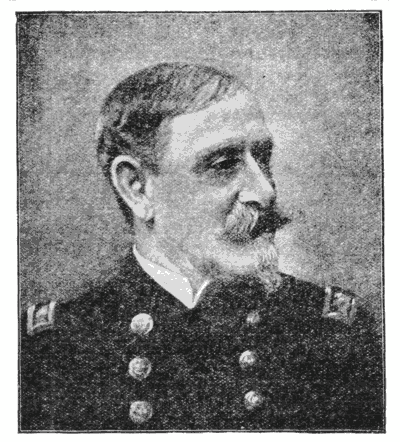

ADMIRAL GEORGE DEWEY, U.S.N.

ADMIRAL GEORGE DEWEY, U.S.N.

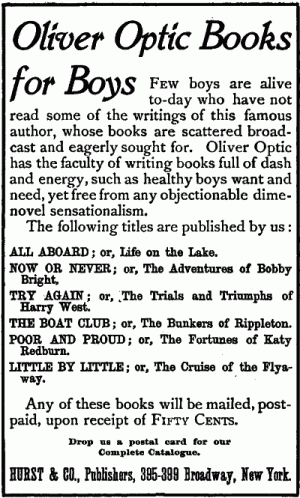

Project Gutenberg's Dewey and Other Naval Commanders, by Edward S. Ellis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Dewey and Other Naval Commanders Author: Edward S. Ellis Release Date: December 8, 2005 [EBook #17253] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEWEY AND OTHER NAVAL COMMANDERS *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Paul Ereaut and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

ADMIRAL GEORGE DEWEY, U.S.N.

ADMIRAL GEORGE DEWEY, U.S.N.

| CHAPTER | ||

| INTRODUCTION | ||

| I | Admiral George Dewey—The Birth and Boyhood of George Dewey. | |

| II | Dewey in the War for the Union. | |

| III | Dewey in the War with Spain. | |

| THE REVOLUTIONARY BATTLES | ||

| IV | Birth of the American Navy—The Privateers—Capture of New Providence, in the Bahamas—Paul Jones—A Clever Exploit—A Skilful Escape—Fine Seamanship—An Audacious Scheme. | |

| V | A Daring Attempt by Captain Paul Jones—Why It Failed—A Bold Scheme—Why It Did Not Succeed—The Fight Between the Ranger and Drake. | |

| VI | One of the Most Memorable Sea Fights Ever Known—The Wonderful Exploit of Captain Paul Jones. | |

| VII | Our Naval War with France—The Tribute Paid to the Barbary States by Christian Nations—War Declared Against the United States by Tripoli—Bainbridge, Decatur, Stewart, Dale and Preble. | |

| VIII | The First Serious Engagement—Loss of the Philadelphia—The Scheme of Captain Bainbridge—Exploit of Lieutenant Decatur. | |

| IX | Bombardment of Tripoli—Treacherous Act of a Turkish Captain—A Quick Retribution at the Hands of Captain Decatur. | |

| X | The Bomb Ketch—A Terrible Missile—Frightful Catastrophe—Diplomacy in Place of War—Peace. | |

| THE WAR OF 1812 | ||

| XI | Cause of the War of 1812—Discreditable Work of the Land Forces—Brilliant Record of the Navy—The Constitution—Captain Isaac Hull—Battle Between the Constitution and Guerriere—Winning a Wager. | |

| XII | Jacob Jones—The Wasp and the Frolic—James Biddle—The Hornet and the Penguin—A Narrow Escape. | |

| XIII | Captains Carden and Decatur—Cruise of the Macedonian—Battle with the Frigate United States—Decatur's Chivalry. | |

| XIV | Occasional American Defeats as Well as Victories—Captain Decatur's Misfortune—The Chesapeake and Shannon. | |

| XV | David Porter—A Clever Feat—Numerous Captures by the Essex—Her Remarkable Cruise in the Pacific—Her Final Capture. | |

| XVI | Oliver Hazard Perry—Prompt and Effective Work—"We Have Met the Enemy and They Are Ours"—Death of Perry. | |

| XVII | A Hero of the Olden Days—Cruise of the Constitution— Her Capture of the Cyane and Levant—Reminiscences of Admiral Stewart—His Last Days. | |

| XVIII | Captures Made After the Signing of the Treaty of Peace—The Privateers—Exploit of the General Armstrong—Its Far-Reaching Result. | |

| LESSER WARS | ||

| XIX | Resentment of the Barbary States—The War with Algiers—Captain Decatur's Vigorous Course—His Astonishing Success as a Diplomat. | |

| XX | Piracy in the West Indies—Its Cause—Means by Which It Was Wiped Out—Piracy in the Mediterranean. | |

| XXI | The Qualla Battoo Incident. | |

| XXII | Wilkes's Exploring Expedition. | |

| THE WAR FOR THE UNION | ||

| XXIII | A New Era for the United States Navy—Opening of the Great Civil War—John Lorimer Worden—Battle Between the Monitor and Merrimac—Death of Worden. | |

| XXIV | Two Worthy Sons—William D. Porter—The Career of Admiral David Dixon Porter. | |

| XXV | Charles Stewart Boggs—His Coolness in the Presence of Danger—His Desperate Fight Below New Orleans—His Subsequent Services. | |

| XXVI | John Ancrum Winslow—His Early Life and Training—The Famous Battle Between the Kearsarge and Alabama. | |

| XXVII | An Unexpected Preacher—Andrew Hull Foote—His Character and Early Career—His Brilliant Services in the War for the Union. | |

| XXVIII | A Man Devoid of Fear—William Barker Cushing—Some of His Exploits—The Blowing Up of the Albemarle—His Sad Death. | |

| XXIX | The Greatest of Naval Heroes—David Glasgow Farragut. | |

| THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR | ||

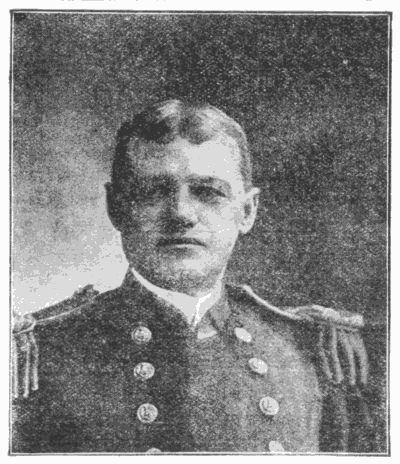

| XXX | The Movement Against Cuba—The Destruction of Cervera's Fleet—Admiral Sampson—Admiral Schley—"Fighting Bob" Evans—Commodore John C. Watson—Commodore John W. Philip—Lieutenant Commander Richard Wainwright. |

I purpose telling you in the following pages about the exploits of the gallant men who composed the American Navy, beginning with the Revolution and ending with the story of their wonderful deeds in our late war with Spain. You can never read a more interesting story, nor one that will make you feel prouder of your birthright. While our patriot armies have done nobly, it is none the less true that we never could have become one of the greatest nations in the world without the help of our heroic navy. Our warships penetrated into all waters of the globe, and made people, whether barbarous or civilized, respect and fear the Stars and Stripes.

This is due in a great measure to the bravery of our naval heroes, who did not fear to meet Great Britain, the "mistress of the seas," when her navy outnumbered ours one hundred to one. England is now our best friend, and no doubt will always remain so. Never again can there be war between her and us, and it will not be strange that one of these days, if either gets into trouble, the American and English soldiers will "drink from the same canteen," which is another way of saying they will fight side by side, as they did [Pg 6]a short time ago in Samoa. All the same, our brethren across the ocean are very willing to own that we fought them right well. Indeed, they think all the more of us for having done so. You know that one brave man always likes another who is as brave as himself, just as Northerners and Southerners love each other, and are all united under one flag, which one side defended and the other fought against, through long years, terrible years from 1861 to 1865.

The decks of no ships have ever been trodden by braver men than our American sailors. There are no more heroic deeds in all history than those of Paul Jones, Porter, Hull, Decatur, Perry, Cushing, Farragut, Worden, Dewey, Schley, Evans, Philip, Hobson and scores of others, who have braved what seemed certain death for the glory of our flag. Many gave up their lives in its defence, and their names form one of the proudest and most cherished heritages that can descend to a grateful country.

So, I repeat, I am sure you will be interested and instructed in learning the story of the heroes who have done so much for us; and their example cannot fail to inspire you with loftier heroism, greater devotion, and deeper resolve to do all you can for our favored land, which is the fairest that ever sun shone upon.

E.S.E.

The name of Vermont recalls the gallant "Green Mountain Boys," who proved their sturdy patriotism not only in the Revolution, but before those stormy days broke over the land. In the colonial times the section was known as the "New Hampshire Grants," and was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire, but Vermont refused to acknowledge the authority of either, even after New York, in 1764, secured a decision in her favor from King George, and set vigorously to work to compel the settlers to pay a second time for their lands. The doughty pioneers would have none of it, and roughly handled the New York officers sent thither. In 1777 Vermont formally declared her independence and adopted a State constitution. Then, since the Revolution was on, Ethan Allen and the rest of the "Green Mountain Boys" turned in and helped whip the redcoats. That being done, Vermont again as[Pg 8]serted her independence, compelled New York to recognize it in 1789, and she was admitted to the Union in 1791.

It was away back in 1633 that the first Englishman bearing the name of Dewey arrived in Massachusetts with a number of other emigrants. They settled in Dorchester, and in 1636 Thomas Dewey, as he was named, removed to Windsor, Connecticut, where he died in 1648, leaving a widow and five children. Following down the family line, we come to the birth of Julius Yemans Dewey, August 22, 1801, at Berlin, Vermont. He studied medicine, practiced his profession at Montpelier, the capital, and became one of the most respected and widely known citizens of the State. He was married three times, and by his first wife had three sons and one daughter. The latter was Mary, and the sons were Charles, Edward, and George, the last of whom became the famous Admiral of the American navy and the hero of the late war between our country and Spain. He was born in the old colonial house of Dr. Dewey, December 26, 1837.

George was a good specimen of the mischievous, high-spirited and roystering youngster, who would go to any pains and run any risk for the sake of the fun it afforded. This propensity was carried to [Pg 9]such an extent that the youth earned the name of being a "bad boy," and there is no use of pretending he did not deserve the reputation. He gave his parents and neighbors a good deal of anxiety, and Dr. Dewey, who knew how to be stern as well as kind, was compelled more than once to interpose his authority in a way that no lad is likely to forget.

Dr. Dewey was a man of deep religious convictions. In middle life he gave up the practice of medicine and founded the National Life Insurance Company, to whose interests he devoted his time and ability, and met with a good degree of success. George was gifted by nature with rugged health, high spirits and indomitable pluck and fearlessness. None could surpass him in running, leaping, swimming and in boyish sports. He was fond of fishing and of rough games, and as a fighter few of his years could stand in front of him. In numerous athletic trials he was invariably the victor, and it must be admitted that he loved fighting as well as he liked playing ball or fishing. He gave and received hard knocks, and even at that early age showed evidence of the combative, aggressive courage that became so marked a feature of his manhood.

An incident is related by Z.K. Pangborn, the well known editor of New Jersey, who took charge of [Pg 10]the Montpelier school, in which George Dewey was a pupil. The school was notorious for the roughness of a number of its pupils, who had ousted more than one instructor and welcomed the chance to tackle a new one. Master Dewey was the ringleader of these young rebels, and chuckled with delight when the quiet-looking, ordinary-sized teacher sauntered down the highway to begin his duties in the schoolroom.

At the time of the gentleman's appearance George was sitting astride of a big limb in a tree at the side of the road, his pockets bulging with stones, which he was hurling with unpleasant accuracy at every one who came within range. Several youngsters were howling from having served as targets to the urchin up the tree, and as soon as Mr. Pangborn saw how things were going he shouted to Dewey to stop his sport. The boy replied by advising the teacher to go to the hottest region named in works on theology, and, descending the tree, led several young scamps in an attack upon the instructor. There was a lively brush, in which it cannot be said that either party was the victor.

A drawn battle is always unsatisfactory to two armies, and George determined to have it out in the schoolroom with the teacher, who, expecting the struggle, had prepared for it and was as eager as the [Pg 11]boys for the fight. As before, Dewey was the leader in the attack on the pedagogue, who was wiry, active, and strong. He swung his rawhide with a vigor that made Dewey and the others dance, but they pluckily kept up the assault, until the instructor seized a big stick, intended to serve as fuel for the old-fashioned stove, and laid about him with an energy that soon stretched the rebels on the floor.

Then how he belabored them! As fast as one attempted to climb to his feet he was thumped back again by the club that continually whizzed through the air, and if a boy tried to stay the storm by remaining prone, the instructor thumped him none the less viciously. Indeed, matters had got to that point that he enjoyed the fun and was loath to let up, as he felt obliged to do, when the howling rebels slunk to their seats, thoroughly cowed and conquered.

George Dewey was the most battered of the lot and made a sorry sight. In fact, he was so bruised that his teacher thought it prudent to accompany him to his home and explain to his father the particulars of the affray in school. Mr. Pangborn gave a detailed history of the occurrence, to which Dr. Dewey listened gravely. When he understood everything, he showed his good sense by thanking the teacher for having administered the punishment, asking him to [Pg 12]repeat it whenever the conduct of his son made it necessary.

This chastisement marked a turning point in the boy's career. He did a good deal of serious thinking throughout the day, and saw and felt his wrongdoing. He became an attentive, obedient pupil, and years after, when grown to manhood, he warmly thanked Mr. Pangborn for having punished him with such severity, frankly adding: "I believe if you hadn't done so I should have ended my career in the penitentiary."

Dr. Dewey wished to give George a career in the army, and he sent him to Norwich University, a military training school, in order to fit him for the Military Academy at West Point. George's tastes, however, were for the navy, and after much pleading with his father he brought him to his way of thinking. The utmost that Dr. Dewey could do was to secure the appointment of his son as alternate, who, as may be understood, secures the appointment only in the event of the principal failing to pass the entrance examination. In this case the principal would have passed without trouble, and, to quote an ordinary expression, George Dewey would have been "left," had not the mother of the other boy interposed at the critical moment. Under no circum[Pg 13]stances would she allow her son to enter the navy. He was compelled to give up all ambition in that direction and to take up the study of theology. At this writing he is a popular preacher, who will always believe it was a most providential thing for our country that turned him aside from blocking the entrance of George Dewey to the Naval Academy at Annapolis.

Our hero entered the institution September 23, 1854. It did not take him long to discover that the institution, like that at West Point, is controlled by the most rigid discipline possible. No stricter rules can be devised than those that prevail at the two institutions. I have heard it said by a West Point graduate that a cadet cannot sit down and breathe for twenty-four hours without violating some rule. The fact that a few men do escape being "skinned"—that is, punished for derelictions of duty—does not prove that they have not committed any indiscretions, but that they have escaped detection.

Hard, however, as was the road for Dewey to travel, he never shrank or turned aside, for he knew the same path had been traveled by all who had gone before him, and he reasoned that what man had done man could do, and he did it.

It will be noted that the future Admiral entered [Pg 14]the Naval Academy at a stirring period in the history of our country, over which the coming Civil War already cast its awful shadow, and, as the months and years passed, the shadow darkened and grew more portentous until the red lightning rent the clouds apart and they rained blood and fire and woe and death.

At the Annapolis Academy the lines between the cadets from the North and the South were sharply drawn. They reflected the passions of their sections, and, being young and impulsive, there were hot words and fierce blows. As might be supposed, George Dewey was prominent in these affrays, for it has been said of him that there was never a fight in his neighborhood without his getting into the thickest of it.

One day a fiery Southerner called him a dough-face, whereupon Dewey let go straight from the shoulder and his insulter turned a backward somersault. Leaping to his feet, his face aflame with rage, he went at the Green Mountain Boy, who coolly awaited his attack, and they proceeded instantly to mix it up for some fifteen minutes in the most lively manner conceivable. At the end of that time the Southerner was so thoroughly trounced that he was unable to continue the fight.

[Pg 15]It was not long before Dewey had a furious scrimmage with another cadet, whom he soundly whipped. He challenged Dewey to a duel, and Dewey instantly accepted the challenge. Seconds were chosen, weapons provided and the ground paced off. By that time the friends of the two parties, seeing that one of the young men, and possibly both, were certain to be killed, interfered, and, appealing to the authorities of the institution, the deadly meeting was prevented. These incidents attest the personal daring of Admiral Dewey, of whom it has been said that he never showed fear of any living man. Often during his stirring career was the attempt made to frighten him, and few have been placed in so many situations of peril and come out of them alive, but in none did he ever display anything that could possibly be mistaken for timidity. He was a brave man and a patriot in every fibre of his being.

A youth can be combative, personally brave and aggressive, and still be a good student, as was proven by the graduation of Dewey, fifth in a class of fourteen. As was the custom, he was ordered to a cruise before his final examination. He was a cadet on the steam frigate Wabash, which cruised in the Mediterranean squadron until 1859, when he returned to Annapolis and, upon examination, took rank as the [Pg 16]leader of his class, proof that he had spent his time wisely while on what may be called his trial cruise. He went to his old home in Montpelier, where he was spending the days with his friends, when the country was startled and electrified by the news that Fort Sumter had been fired on in Charleston harbor and that civil war had begun. Dewey's patriotic blood was at the boiling point, and one week later, having been commissioned as lieutenant and assigned to the sloop of war Mississippi, he hurried thither to help in defence of the Union.

The Mississippi was a sidewheel steamer, carrying seventeen guns, and was destined to a thrilling career in the stirring operations of the West Gulf squadron, under the command of Captain David Glasgow Farragut, the greatest naval hero produced by the Civil War, and without a superior in all history.

No one needs to be reminded that the War for the Union was the greatest struggle of modern times. The task of bringing back to their allegiance those who had risen against the authority of the National Government was a gigantic one, and taxed the courage and resources of the country to the utmost. In order to make the war effective, it was necessary to enforce a rigorous blockade over three thousand miles of seacoast, open the Mississippi river, and overcome the large and well-officered armies in the field. The last was committed to the land forces, and it proved an exhausting and wearying struggle.

Among the most important steps was the second—that of opening the Mississippi, which being accomplished, the Southwest, from which the Confederacy drew its immense supplies of cattle, would be cut off and a serious blow struck against the armed rebellion.

The river was sealed from Vicksburg to the Gulf of Mexico. At the former place extensive batteries had been erected and were defended by an army, [Pg 18]while the river below bristled with batteries and guns in charge of brave men and skilful officers.

While General Grant undertook the task of reducing Vicksburg, Captain Farragut assumed the herculean work of forcing his way up the Mississippi and capturing New Orleans, the greatest commercial city in the South. Knowing that such an attack was certain to be made, the Confederates had neglected no precaution in the way of defence. Ninety miles below the city, and twenty miles above its mouth, at the Plaquemine Bend, were the forts of St. Philip and Jackson. The former, on the left bank, had forty-two heavy guns, including two mortars and a battery of four seacoast mortars, placed below the water battery. Fort Jackson, besides its water battery, mounted sixty-two guns, while above the forts were fourteen vessels, including the ironclad ram Manassas, and a partially completed floating battery, armored with railroad iron and called the Louisiana. New Orleans was defended by three thousand volunteers, most of the troops formerly there having been sent to the Confederate army in Tennessee.

The expedition against New Orleans was prepared with great care, and so many months were occupied that the enemy had all the notice they could ask in which to complete their preparations for its defence. [Pg 19]The Union expedition consisted of six sloops of war, sixteen gunboats, twenty mortar schooners and five other vessels. The Mississippi, upon which young Dewey was serving as a lieutenant, was under the command of Melanethon Smith. The land troops numbered 15,000, and were in charge of General Benjamin F. Butler, of Massachusetts.

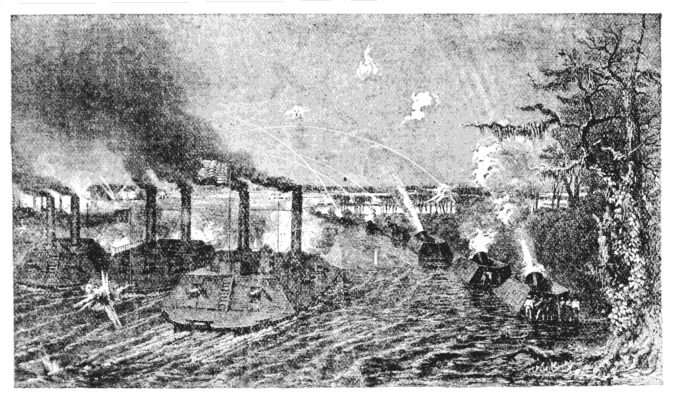

Farragut arrived in February, 1862, nearly two months after the beginning of preparations to force the river. When everything was in readiness the fleet moved cautiously up stream, on April 18, and a bombardment of Forts St. Philip and Jackson was opened, which lasted for three days, without accomplishing anything decisive. Farragut had carefully studied the situation, and, confident that the passage could be made, determined it should be done, no matter at what cost. On the night of the 23d his vessels were stripped of every rope and spar that could be spared, the masts and rigging of the gunboats and mortar vessels being trimmed with the limbs of trees, to conceal their identity from the Confederate watchers.

At two o'clock in the morning the signal was hoisted on the Hartford, Captain Farragut's flagship, and the fleet started in single line to run the fearful gauntlet. The Cayuga led, the Pensacola followed, [Pg 20]and the Mississippi was third. The rebels had huge bonfires burning on both shores, and as the Pensacola came opposite the forts they opened their furious fire upon her.

A good deal of uneasiness prevailed in the Union fleet regarding the rebel rams. It was known they were formidable monsters, which the Confederates believed could smash and sink the whole Union squadron. While it was known that much was to be feared from the forts, it was the ironclads that formed the uncertain factor and magnified the real danger in many men's minds.

The Mississippi was hardly abreast of Fort St. Philip when the dreaded Manassas came plunging down the river out of the gloom at full speed, and headed directly for the Mississippi. She was not seen until so close that it was impossible to dodge her, and the ironclad struck the steamer on the port side, close to the mizzenmast, firing a gun at the same time. Fortunately the blow was a glancing one, though it opened a rent seven feet long and four inches deep in the steamer, which, being caught by the swift current on her starboard bow, was swept across to the Fort Jackson side of the river, so close indeed that her gunners and those in the fort exchanged curses and imprecations.

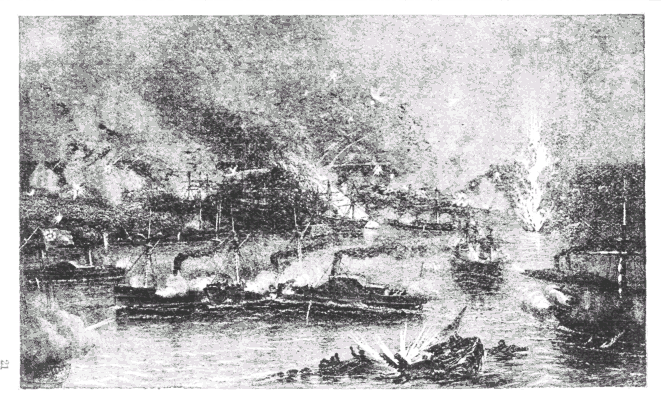

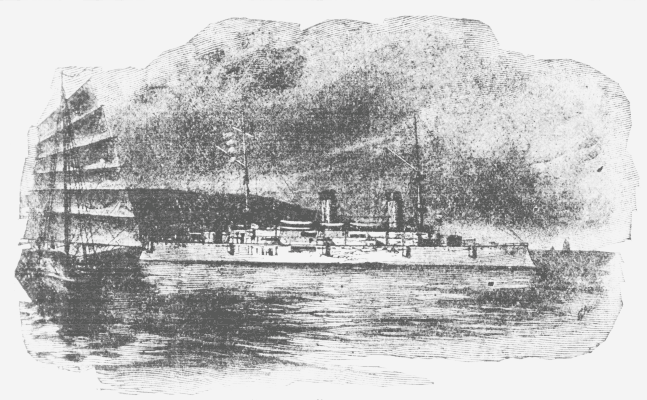

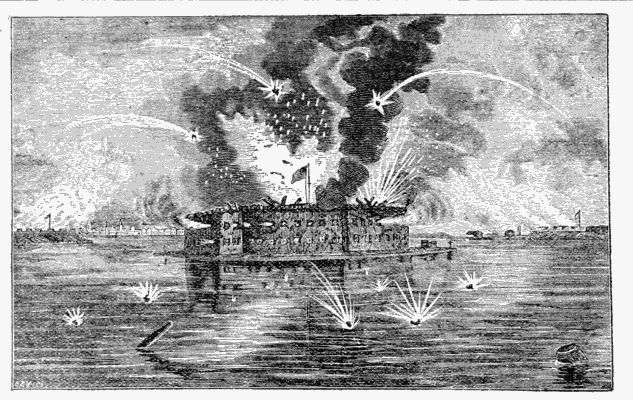

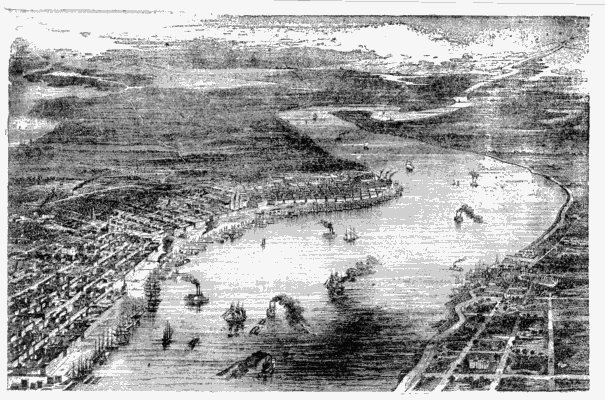

SHELLING FORTS PHILIP AND JACKSON.

SHELLING FORTS PHILIP AND JACKSON.

[Pg 22]The passage of the forts by the Union vessels forms one of the most thrilling pictures in the history of the Civil War. The Hartford, like all the vessels, was subjected to a terrible fire, was assailed by the Confederate ironclads, and more than once was in imminent danger of being sent to the bottom. Following with the second division, Captain Farragut did not reply to the fire of the forts for a quarter of an hour. He hurled a broadside into St. Philip and was pushing through the dense smoke when a fire-raft, with a tug pushing her along, plunged out of the gloom toward the Hartford's port quarter. She swerved to elude this peril and ran aground close to St. Philip, which, recognizing her three ensigns and flag officer's flag, opened a savage fire, but luckily most of the shot passed too high.

There was no getting out of the way of the fire-raft, which, being jammed against the flagship, sent the flames through the portholes and up the oiled masts. The perfect discipline of the crew enabled them to extinguish the fire before it could do much damage, and the Hartford succeeded in backing into deep water and kept pounding Fort St. Philip so long as she was in range.

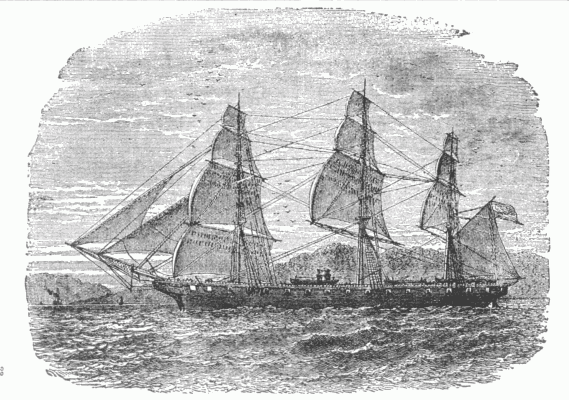

THE "HARTFORD"—FARRAGUT'S FLAGSHIP.

THE "HARTFORD"—FARRAGUT'S FLAGSHIP.

Without attempting to describe the battle in detail, we will give our attention to the Mississippi. [Pg 24]Within an hour and a quarter of the time the leading vessel passed the forts, all had reached a safe point above, where they engaged in a furious fight with the Confederate flotilla, the smaller members of which were soon disabled or sunk.

Meanwhile the ironclad Manassas had been prowling at the heels of the Union squadron, but being discovered by the Mississippi, the steamer opened on her with so destructive a fire that the ram ran ashore and the crew scrambled over the bows and escaped. The Mississippi continued pounding her until she was completely wrecked. The loss of the Union fleet was thirty-seven killed and one hundred and forty-seven wounded, while the Confederate land forces had twelve killed and forty wounded. The Confederate flotilla must have lost as many men as the Unionists. Having safely passed all obstructions, Captain Farragut steamed up to the river to New Orleans, and the city surrendered April 25, formal possession being taken on May 1.

It will be admitted that Lieutenant Dewey had received his "baptism of fire."

It is the testimony of every one who saw him during the turmoil of battle that he conducted himself with the coolness and courage of a veteran. At no time during the passage of the forts and the desperate fighting with the Confederate flotilla above did he display the first evidence of nervousness or lack of self-possession.

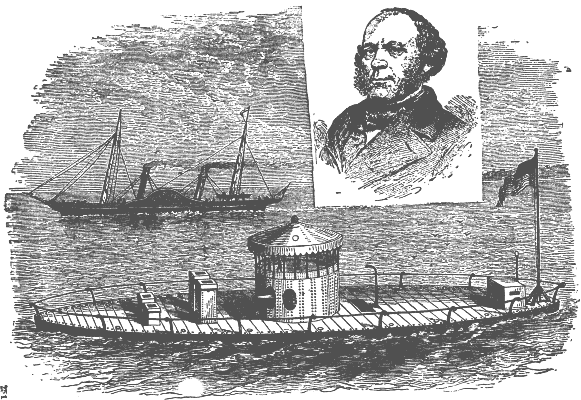

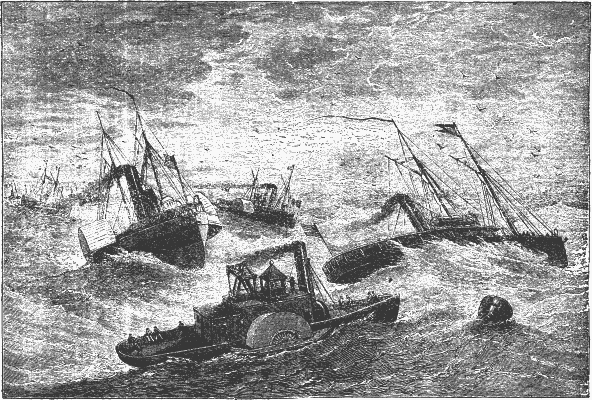

IRONCLADS ON THE MISSISSIPPI.

IRONCLADS ON THE MISSISSIPPI.

The next engagement in which Lieutenant Dewey took part was the attempt by Farragut to pass the battery of nineteen guns, mounted on the hundred-foot high bluff of Port Hudson, on a bend of the Mississippi, below Vicksburg. The position was the most difficult conceivable to carry from the river, because of the plunging shots from the enormous guns on the bluff above.

Captain Farragut had no thought of reducing these batteries, which would have been impossible with a fleet double the strength of his, but he wished to get his vessels past in order to blockade the river above the bend. The attempt was made on the night of March 14, 1863, with the Hartford in the lead, and followed by the Richmond, Monongahela and Mississippi, with the smaller boats. The first three boats had as consorts the Albatross, Kineo and Genessee. Captain Mahan, in "The Gulf and Inland Waters," gives the following vivid description of this historical incident:

"As they drew near the batteries, the lowest of which the Hartford had already passed, the enemy threw up rockets and opened their fire. Prudence, [Pg 27]and the fact of the best water being on the starboard hand, led the ships to hug the east shore of the river, passing so close under the Confederate guns that the speech of the gunners and troops could be distinguished. Along the shore, at the foot of the bluffs, powerful reflecting lamps, like those used on locomotives, had been placed to show the ships to the enemy as they passed, and for the same purpose large fires, already stacked on the opposite point, were lit. The fire of the fleet and from the shore soon raised a smoke which made these precautions useless, while it involved the ships in a danger greater than any from the enemy's guns. Settling down upon the water in a still, damp atmosphere, it soon hid everything from the eyes of the pilots. The flagship leading had the advantage of pushing often ahead of her own smoke; but those who followed ran into it and incurred a perplexity which increased from van to rear. At the bend of the river the current caught the Hartford on her port bow, sweeping her around with her head toward the batteries, and nearly on shore, her stern touching the ground slightly; but by her own efforts and the assistance of the Albatross she was backed clear. Then, the Albatross backing and the Hartford going ahead strong with the engine, her head was fairly pointed up the stream, and she [Pg 28]passed by without serious injury. Deceived possibly by the report of the howitzers in her top, which were nearly on their own level, the Confederates did not depress their guns sufficiently to hit her as often as they did the ships that followed her. One killed and two wounded is her report; and one marine fell overboard, his cries for help being heard on board the other ships as they passed by, unable to save him."

If the capture of the batteries was impossible, their passage was almost equally so. The Richmond was so badly injured that she was compelled to turn down stream, having suffered a loss of three killed and fifteen wounded, while the Monongahela had six killed and twenty-one wounded before she was able to wrench herself loose from where she had grounded and drift out of range.

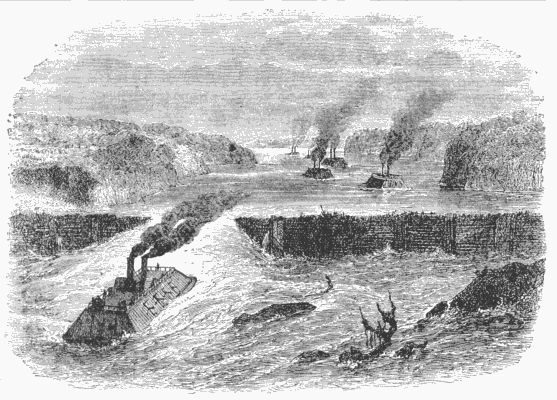

Now came the Mississippi, whose tragic fate is graphically told by Admiral Porter in his "Naval History of the Civil War":

"The steamship Mississippi, Captain Melancthon Smith, followed in the wake of the Monongahela, firing whenever her guns could be brought to bear. At 11:30 o'clock she reached the turn which seemed to give our vessels so much trouble, and Captain Smith was congratulating himself on the prospect of [Pg 29]soon catching up with the flag officer, when his ship grounded and heeled over three streaks to port.

"The engines were instantly reversed and the port guns run in in order to bring her on an even keel, while the fire from her starboard battery was reopened on the forts. The engines were backed with all the steam that could be put upon them, and the backing was continued for thirty minutes, but without avail.

"It was now seen that it would be impossible to get the ship afloat.

"Captain Smith gave orders to spike the port battery and throw the guns overboard, but it was not done, for the enemy's fire was becoming so rapid and severe that the Captain deemed it judicious to abandon the ship at once in order to save the lives of the men.

"While preparations were being made to destroy the ship, the sick and wounded were lowered into boats and conveyed ashore, while the men at the starboard battery continued to fight in splendid style, firing at every flash of the enemy's guns. The small arms were thrown overboard, and all possible damage was done to the engine and everything else that might prove of use to the enemy.

"The ship was first set on fire in the forward store[Pg 30]room, but three shots came through below her water-line and put out the flames. She was then set afire in four places aft, and when the flames were well under way, so as to make her destruction certain, Captain Smith and his first lieutenant (George Dewey) left the ship, all the officers and crew having been landed before.

"The Mississippi was soon ablaze fore and aft, and as she was now relieved of a great deal of weight—by the removal of her crew and the destruction of her upper works—she floated off the bank and drifted down the river, much to the danger of the Union vessels below. But she passed without doing them any injury, and at 5:30 o'clock blew up and went to the bottom."

When the time came for the crew to save themselves as best they could, all sprang overboard and struck out for shore. A little way from the blazing steamer a poor sailor was struggling hard to save himself, but one arm was palsied from a wound, and he must have drowned but for Dewey, who swam powerfully to him, helped him to a floating piece of wreckage and towed him safely to land.

The lieutenant was now transferred to one of the gunboats of Admiral Farragut's squadron and engaged in patrol duty between Cairo and Vicksburg.

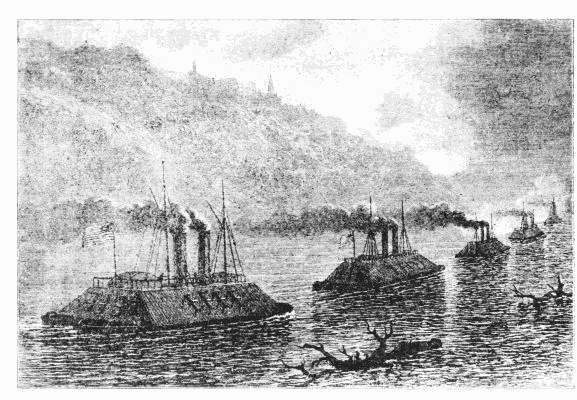

GUNBOATS PASSING BEFORE VICKSBURG.

GUNBOATS PASSING BEFORE VICKSBURG.

[Pg 32]The latter surrendered to General Grant July 4, 1863, and the river was opened from its source to the Gulf. Early in 1864 the lieutenant was made executive officer of the gunboat Agawam, and when attached to the North Atlantic squadron, took part in the attack on Fort Fisher, one of the strongest of forts, which, standing at the entrance of Cape Fear river, was so efficient a protection to Wilmington that the city became the chief port in the Confederacy for blockade runners. Indeed, its blockade was a nullity, despite the most determined efforts of the Union fleet to keep it closed. The Confederate cruisers advertised their regular days for departure, and they ran upon schedule time, even women and children taking passage upon the swift steamers with scarcely a fear that they would not be able to steam in and out of the river whenever the navigators of the craft chose to do so.

The first attempt against Fort Fisher was in the latter part of December, 1864, but, though the fleet was numerous and powerful, and the greatest gallantry was displayed, the attack was unsuccessful. General Butler, in command of the land troops, after a careful examination of the Confederate works, pronounced capture impossible and refused to sacrifice his men in a useless attack. Nevertheless the attempt [Pg 33]was renewed January 12, when General Alfred Terry had charge of the land forces. The garrison made one of the bravest defences of the whole war, and the hand-to-hand fight was of the most furious character. It lasted for five hours, when the fort was obliged to surrender, the garrison of 2,300 men becoming prisoners of war. It was in this fearful struggle that Ensign "Bob" Evans, who was with the naval force that charged up the unprotected beach, was so frightfully wounded that it was believed he could not live. When the surgeon made ready to amputate his shattered leg, Bob, who had secured possession of a loaded revolver, swore he would shoot any man who touched the limb with such purpose. Perforce he was left alone, and in due time fully recovered, though lamed for life.

Lieutenant Dewey was one of the most active of the young officers in the attack on Fort Fisher, and conducted himself with so much bravery and skill, executing one of the most difficult and dangerous movements in the heat of the conflict, that he was highly complimented by his superior officers.

But peace soon came, and a generation was to pass before his name was again associated with naval exploits. In March, 1865, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-commander and assigned to duty [Pg 34]on the Kearsarge, the vessel that acquired undying glory for sinking the Alabama, off Cherbourg, France, during the previous July. Early in 1867 he was ordered home from the European station and assigned to duty at the Kittery Navy Yard, at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

While at this station he became acquainted with Miss Susan B. Goodwin, daughter of the "war Governor" of New Hampshire. She was an accomplished young woman, to whom the naval officer was married, October 24, 1867. Their all too brief wedded life was ideally happy, but she died December 28, 1872, a few days after the birth of a son, named George Goodwin, in honor of his grandfather.

From 1873 to 1876 Dewey was engaged in making surveys on the Pacific coast; he commanded the Juniata on the Asiatic squadron in 1882-83, and the following year was made captain and placed in charge of the Dolphin, one of the original "white squadron." Next came service in Washington as Chief of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting, as member of the Lighthouse Board and president of the Board of Inspection and Survey (he being made commodore February 28, 1896), until 1897, when he was placed in command of the Asiatic squadron, much against his will.

While engaged with his duties in Washington, Commodore Dewey found his close confinement to work had affected his health. Naturally strong and rugged, accustomed to the ozone of the ocean and toned up by the variety of the service, even in times of peace, the monotony of a continual round of the same duties told upon him, and his physician advised him to apply for sea service. He knew the counsel was wise and he made application, which was granted.

Assistant Secretary of War Theodore Roosevelt, after a careful study of the record of the different naval commanders, was convinced that George Dewey deserved one of the most important commands at the disposal of the Government. The impetuous official was certain that war with Spain was at hand, and that one of the most effective blows against that tyrannous power could be struck in the far East, where the group of islands known as the Philippines constituted her most princely possessions.

The assignment, as has been stated, was not pleas[Pg 36]ing to Dewey, because he and others believed the real hard fighting must take place in European or Atlantic waters. We all know the uneasiness that prevailed for weeks over the destination of the Spanish fleet under Admiral Cervera. Dewey wanted to meet him and do some fighting that would recall his services when a lieutenant in the Civil War, and he saw no chance of securing the chance on the other side of the world, but Roosevelt was persistent, and, against the wishes of the Naval Board, he obtained his assignment as flag officer of the Asiatic squadron.

Commodore Dewey felt that the first duty of an officer is to obey, and after a farewell dinner given by his friends at the Metropolitan Club in Arlington, he hurriedly completed his preparations, and, starting for Hong Kong, duly reached that port, where, on January 3, 1898, he hoisted his flag on the Olympia.

The official records show that the Olympia was ordered home, but Roosevelt, in a confidential dispatch of February 25, directed Commodore Dewey to remain, to prepare his squadron for offensive operations, and, as soon as war broke out with Spain, to steam to the Philippines and hit the enemy as hard as he knew how. Meanwhile ammunition and supplies were hurried across the continent to San Fran[Pg 37]cisco as fast as express trains could carry them, and were sent thence by steamer to Hong Kong, where they were eagerly received by the waiting Commodore.

Reverting to those stirring days, it will be recalled that the Queen Regent of Spain declared war against the United States on April 24, 1898, to which we replied that war had begun three days earlier, when the Madrid government dismissed our minister and handed him his passports. Then followed, or rather were continued, the vigorous preparations on the part of our authorities for the prosecution of the war to a prompt and decisive end.

Commodore Dewey's squadron lay at anchor in the harbor of Hong Kong, awaiting the momentous news from Washington. When it reached the commander it was accompanied by an order to capture or destroy the enemy's fleet at Manila. Almost at the same time Great Britain issued her proclamation of neutrality, the terms of which compelled Dewey to leave the British port of Hong Kong within twenty-four hours. He did so, steaming to Mirs Bay, a Chinese port near at hand, where he completed his preparations for battle, and on the 27th of April steamed out of the harbor on his way to Manila.

[Pg 38]The city of Manila, with a population numbering about a quarter of a million, lies on the western side of Luzon, the principal island, with a magnificent bay in front, extensive enough to permit all the navies of the world to manœuvre with plenty of elbow room. The entrance to the immense bay is seven miles wide and contains two islands, Corregidor and Caballo, both of which were powerfully fortified, the works containing a number of modern guns. Torpedoes were stretched across the channel and the bay abounded with enough mines and torpedoes, it would seem, to blow any fleet of ironclads to atoms as soon as it dared to try to force an entrance into the waters. Some twenty miles beyond lay the city of Manila, and about ten miles to the south was Cavité, constituting the strongly fortified part of the city proper.

Of course the Spanish spies were on the watch in Hong Kong, and while the American squadron was steaming out of the bay the news was telegraphed to the authorities at Manila, who knew that the real destination of the enemy was that city. Every effort was made to keep the matter a secret, but it was impossible, and it soon became known to everybody that the American "pigs" were coming, and that Manila must fall, if the Spanish fleet were unable to beat off the enemy.

[Pg 39]The Spaniards proclaimed that they would send every one of the American vessels to the bottom; but they had made similar boasts before, and their bombast did not quiet the fears of the people, among whom a panic quickly spread. Those who were able to do so gathered their valuables and took refuge on the merchant ships in the harbor and thanked heaven when they bore them away. Many others fled from the city, but the majority stayed, grimly determined to be in at the death and accept whatever fate was in store for them.

The distance between Hong Kong and Manila is 630 miles, and it needed only a little figuring on the part of the inhabitants to decide that the dreaded squadron would be due on the following Saturday evening or early the next morning, which would be the first of May. The self-confidence of Admiral Montojo and his officers was almost sublime. All they asked was a fair chance at the "American pigs." They hoped that nothing would occur to prevent the coming of the fleet, for the Spaniards would never cease to mourn if the golden opportunity were allowed to slip from their grasp. They were not disappointed in that respect.

It is proper to give at this point the respective strength of the American and Spanish fleets. The [Pg 40]squadron under the command of Commodore Dewey was as follows:

Olympia—Protected cruiser (flagship), 5,500 tons. Speed, 21.7 knots. Complement, 450. Armor, protected deck, 2 inches to 4-3/4 inches. Guns, main battery, four 8-inch, ten 5-inch, rapid-fire; secondary battery, rapid-fire, fourteen 6-pound, seven 1-pound, four Gatlings, one field gun and five torpedo tubes. Captain Charles V. Gridley.

Baltimore—Protected cruiser, 4,400 tons. Speed, 20.1 knots. Complement, 386. Armor, 2-1/2 inches to 4 inches. Guns, main battery, four 8-inch, six 6-inch, slow-fire; secondary battery, rapid-fire, four 6-pound, two 3-pound, two 1-pound, four 37 MM. Hotchkiss, two Colts, one field gun and five torpedo tubes. Captain N.M. Dyer.

Raleigh—Protected cruiser, 3,213 tons. Speed, 19 knots. Armor, 1 inch to 2-1/2 inches. Guns, one 6-inch, rapid-fire, ten 5-inch; secondary battery, eight 6-pounders, four 1-pounders, and two machine guns. Complement, 320. Captain J.B. Coghlan.

Boston—Protected cruiser, 3,189 tons. Speed, 15.6 knots. Complement, 270. Armor, 1-1/2 inch deck. Guns, main battery, two 8-inch and six 6-inch rifles; secondary battery, rapid-fire, two 6-pounders and two 3-pounders. Captain F. Wildes.

[Pg 41]Petrel—Fourth-rate cruiser, 890 tons. Speed, 13.7 knots. Guns, four 6-inch, two 3-pounder rapid-fire, one 1-pounder, and four machine guns. Commander E.P. Wood.

Concord—Gunboat, 1,710 tons. Speed, 16.8 knots. Armor, 3/8-inch deck. Guns, main battery, six 6-inch rifles. Commander Asa Walker.

Hugh McCulloch—Revenue cutter, light battery of rapid-fire guns.

Zafiro—Auxiliary cruiser: supply vessel.

The vessels under command of Admiral Montojo were the following:

Reina Cristina—Cruiser (flagship). Built in 1887, iron, 3,090 tons, 14 to 17.5 knots, according to draught, and a main battery of six 6.2-inch rifles.

Castilla—Cruiser, built in 1881, wood, 3,342 tons, 14 knots, and four 5.9-inch Krupps and two 4.7-inch Krupps in her main battery.

Velasco—Small cruiser, built in 1881, iron, 1,139 tons, and three 6-inch Armstrongs in her main battery.

Don Juan de Austria—Small cruiser, completed in 1887, iron, 1,152 tons, 13 to 14 knots, and four 4.7-inch rifles in her main battery.

Don Antonio de Ulloa—Small cruiser, iron, 1,152 [Pg 42]tons. Four 4.7-inch Hontoria guns; two 2.7-inch, two quick-firing; two 1.5-inch; five muzzle loaders.

Gunboats Paragua, Callao, Samar, Pampagna, and Arayat, built 1881-6, steel, 137 tons, 10 knots, and each mounting two quick-firing guns.

Gunboats Mariveles and Mindoro, built in 1886 and 1885, iron, 142 tons, 10 knots, each mounting one 2.7-inch rifle and four machine guns.

Gunboat Manileno, built in 1887, wood, 142 tons, 9 knots, and mounting three 3.5-inch rifles.

Gunboats El Cano and General Lezo, built in 1885, iron, 528 tons, 10 to nearly 12 knots, and each mounting three 3.5-inch rifles.

Gunboat Marquis Del Duero, built in 1875, iron, 500 tons, 10 knots, and mounting one 6.2-inch and two 4.7-inch rifles.

Through the bright sunshine and when the stars twinkled in the sky or the full moon rode overhead, the American ships steamed to the southeast across the heaving China Sea. The Stars and Stripes fluttered in the breeze and there was a feeling of expectancy on board the grim engines of war, that had laid aside every possible encumbrance, and like prize-fighters were stripped to the buff and eager for battle.

[Pg 43]The run was a smooth one, and as the sun was sinking in the sky Commodore Dewey, peering through his glass, caught the faint outlines of Corregidor Island, and dimly beyond the flickering haze revealed the Spanish fleet in the calm bay. The Commodore had been in that part of the world before, and while waiting at Hong Kong had gathered all the knowledge possible of the defences of Manila. He knew the fort was powerfully fortified and the bay mined, and knowing all this, he remembered the exclamation of his immortal instructor in the science of war, the peerless Farragut, when he was driving his squadron into Mobile Bay. Recalling that occurrence, Commodore Dewey joined in spirit in repeating the words:

"D—— the torpedoes!"

It was still many miles to the entrance, and night closed in while the squadron was ploughing through the sea that broke in tumbling foam at the bows and spread far away in snowy wakes at the rear. All lights were put out, the full moon again climbed the sky and the shadowy leviathans plunged through the waters straight for the opening of the bay, guarded by the fort and batteries, with the Spanish fleet beyond, defiantly awaiting the coming of the American squadron.

[Pg 44]Suddenly from Corregidor Island the darkness was lit up by a vivid flash, a thunderous boom traveled across the bay, and the heavy shot tore its way screaming over the Raleigh, quickly followed by a second, which fell astern of the Olympia and Raleigh. The Spaniards had discovered the approach of the squadron. The Raleigh, Concord, and Boston replied; all the shots being fired with remarkable accuracy.

One may imagine the consternation in Manila when the boom of those guns rolled in from the bay, for none could mistake its meaning. Women and children ran to the churches and knelt in frenzied prayer; men dashed to and fro, not knowing what to do, while the Spanish soldiers, who had not believed the American ships could ever pass the harbor torpedoes and mines, were in a wild panic when they learned that the seemingly impossible had been done. To add to the terror, rumors spread that the ferocious natives were gathering at the rear of the city to rush in and plunder and kill.

When at last the morning light appeared in the sky, the Americans saw tens of thousands of people crowded along the shore, gazing in terror out on the bay where rode the hostile fleets, soon to close in deadly battle. Commodore Dewey coolly scanned the hostile vessels, and grasping the whole situation, [Pg 45]as may be said, at a glance, led in the attack on the enemy.

While approaching Cavité two mines exploded directly in front of the Olympia. The roar was tremendous and the water was flung hundreds of feet in the air. Without swerving an inch or halting, Dewey signalled to the other vessels to pay no attention to the torpedoes, but to steam straight ahead. It was virtually a repetition of the more emphatic command of Farragut in Mobile Bay, uttered thirty-four years before.

The batteries on shore let fly at the ships, and the first reply was made by Captain Coghlan of the Raleigh. The Olympia had led the way into the harbor, and she now headed for the centre of the Spanish fleet. Calmly watching everything in his field of vision, and knowing when the exact moment arrived for the beginning of the appalling work, Commodore Dewey, cool, alert, attired in white duck uniform and a golf cap, turned to Captain Gridley and said in his ordinary conversational tone:

"Gridley, you may fire when ready."

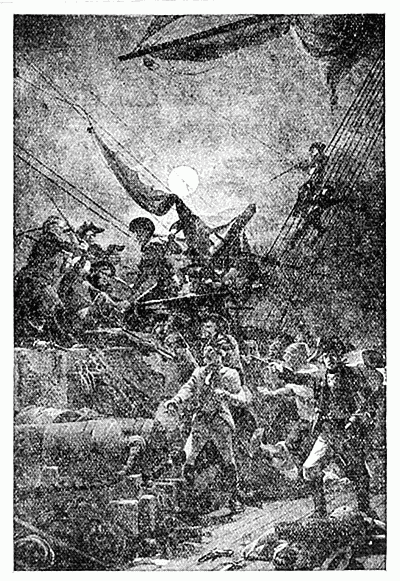

A series of sharp, crackling sounds followed, like exploding Chinese crackers, and then the thunderous roars and a vast volume of smoke rolled over the bay and enveloped the warships that were pouring their [Pg 46]deadly fire into the Spanish vessels. The American ships, in order to disconcert the aim of the batteries of the enemy, moved slowly in their terrible ellipses or loops, their sides spouting crimson flame and answered by the shots of the Spaniards, who fought with a courage deserving of all praise. The manœuvring of the American ships led the breathless swarms on shore to believe they were suffering defeat, and an exultant telegram to that effect was cabled to Madrid, nearly ten thousand miles away, where it caused a wild but short-lived rejoicing.

At half-past seven there was a lull. Commodore Dewey drew off to replenish his magazines, of whose shortness of supply he had received disturbing reports. Advantage was taken of the cessation to give the men breakfast, for it is a well accepted principle that sailors as well as soldiers fight best upon full stomachs. As the wind blew aside the dense smoke, it was seen that the Reina Cristina, the Spanish flagship, was in flames. Hardly two hours later the American squadron advanced again to the attack, and Admiral Montojo was observed to transfer his flag from the doomed Reina Cristina to the Isla de Cuba, which soon after was also ablaze. Amid the crash and roar of the ponderous guns sounded the shrieks and cries of mortal agony from the Spanish [Pg 47]crews, victims to the matchless gunnery of the Americans.

THE "OLYMPIA" IN MANILA BAY.

THE "OLYMPIA" IN MANILA BAY.

The latter pressed their advantage remorselessly. The Don Juan de Austria was the centre of the heaviest fire, and suddenly a part of the deck flew upward in the air, carrying with it scores of dead and wounded. A shot had exploded one of her magazines, and at the sight of the awful results Admiral Montojo threw up his arms in despair. The crew refused to leave the blazing ship, and cursing and praying they went down with her. Then the Castilla burst into one mass of roaring flame, and the rest of the defeated fleet skurried down the long narrow isle behind Cavité. Others dashed up a small creek, where they grounded, and those that were left ran ashore. By half-past eleven the batteries of Cavité were silenced, the Spanish fleet was destroyed, and the victorious Americans broke into ringing cheers. The battle of Manila, one of the most remarkable in naval annals, was won and Commodore Dewey took rank among the greatest of all the heroes of the sea.

What a marvellous record! Of the Spaniards, the dead and wounded numbered nearly a thousand, while not a single life had been lost by the American squadron. Several were wounded, but none seriously. No such victory between ironclads has thus [Pg 49]far taken place in the history of the world. In the face of mines, torpedoes and shore batteries, Commodore Dewey had won an overwhelming and crushing victory. The power of Spain in the Philippines was forever destroyed, and another glorious victory had been added to the long list that illumines the story of the American navy.

It was easy for Dewey to compel the surrender of Manila, but with the prudence that always guides him, he decided that since his force was not strong enough to occupy and hold the city, to await the arrival of reinforcements from the United States. They reached Manila the following August, and, under command of General Wesley Merritt and aided by the fleet, Manila surrendered, almost at the same hour that the representatives of Spain and our own officials in Washington signed the protocol that marked the cessation of war between the two countries.

Now came long and trying weeks and months to Rear Admiral Dewey, he having been promoted upon receipt of news of his great victory. Peerless as was his conduct during offensive operations, it was surpassed in many respects by his course throughout the exasperating period named. Germany and France were unfriendly and Aguinaldo treacherous, though [Pg 50]Great Britain and Japan were ardent in their sympathy for the United States. Germany especially was a constant cause of irritation to Admiral Dewey, whose patience was often tried to the utmost verge. To his tact, prudence, self-control, firmness, diplomacy and masterful wisdom were due the fact that no complication with foreign powers occurred and that the United States escaped a tremendous war, whose consequences no one could foresee or calculate.

Everybody instinctively felt that Admiral Dewey was the real hero of our war with Spain. The wish was general that he should return home in order that his countrymen might have opportunity to show their appreciation of him and to give him fitting honors.

And nothing could be more repugnant than all this to the naval hero, who is as modest as he is brave. Besides, he felt that his work was by no means finished in the far East, for, as has been shown, there was need of delicate diplomacy, prudence and statesmanship. He asked to be allowed to stay, and he did so, until, the main difficulty being passed, and his health feeling the result of the tremendous strain that was never relaxed, he finally set sail in the Olympia for home, leaving Hong Kong in May, and, one year after his great victory, proceeding at a leisurely rate that did not bring him to his native shores [Pg 51]until the cool breezes of autumn. On the long voyage hither he was shown the highest honors everywhere, and Washington or Lincoln could not have received more grateful homage than was paid to him by his countrymen, whom he had served so long, so faithfully and so well.

Meanwhile, it should be added, that the rank of full Admiral of the navy, hitherto borne only by David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter, was revived and bestowed, in February, 1899, upon George Dewey, and of the three none has worn the exalted honor more worthily than the Green Mountain Boy, who has proven himself the born gentleman and fighter, the thorough patriot and statesman and the Chevalier Bayard of the American navy.

When, on April 19, 1775, the battle of Lexington opened the Revolution the Colonies did not possess a single ship with which to form the beginning of a navy. They had for many years been actively engaged in the coasting trade and some of their vessels did valiant service on the side of England in the wars against France and Spain. We had a good many hardy, skilled seamen, who formed the best material from which to man a navy, and before long Congress undertook the work of building one. That body ordered the construction of thirteen frigates—one for each State—and some of these did noble work, but by the close of the war few of them were left; nearly all had been captured or destroyed.

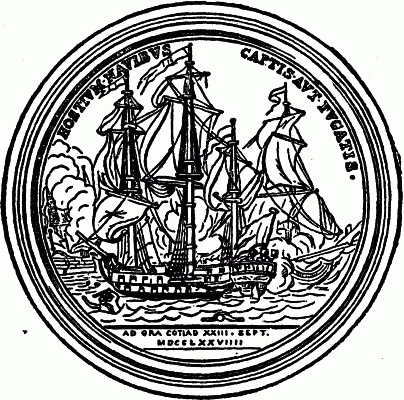

CAPTAIN JOHN PAUL JONES.

CAPTAIN JOHN PAUL JONES.

[Pg 54]It was far different with the privateers, which were vessels fitted out by private parties, under the authority of Congress, to cruise the seas wherever they chose and capture English vessels wherever they could. When a prize was taken the lucky officers and crews divided the plunder. It was a very tempting field for the brave and enterprising Americans and when, in March, 1776, Congress gave them permission to fit out and sail privateers, they were quick to use the chance of securing prize money as it was called. Those swift sailing vessels and their daring crews sailed out of Salem, Cape Ann, Newburyport, Bristol and other seacoast towns, and they did not have to hunt long before they found the richest sort of prizes. In the single year 1776 these privateers captured 342 British vessels and wrought great havoc among the English shipping.

In January, 1778, one of these privateers entered the harbor of New Providence, in the Bahamas, and captured the fort and a sixteen-gun man-of-war. Many other valiant exploits were performed and before long some of the more daring privateers boldly crossed the Atlantic and by their deeds threw the coast of Great Britain into consternation.

Among the most remarkable of these naval heroes was a young Scotchman, not quite thirty years old.

He had been trained in the merchant service and had become a skilful sailor before he removed to Virginia, where he made his home. He devotedly loved his adopted country, and, when the war broke out between the colonies and Great Britain, and the long, hard struggle for independence began, he was among the very first to offer his services on the side of liberty. His character was so well known and appreciated that he was appointed a first lieutenant. I am sure you have all heard of him, for his name was John Paul Jones, though since, for some reason [Pg 56]or other, he dropped his first name and is generally referred to simply as Paul Jones.

His first service was on the Alfred, which helped in the capture of the fort at New Providence, already spoken of. Jones with his own hands hoisted the first flag displayed on an American man-of-war. It was of yellow silk, with the device of a rattlesnake, and bore the motto, "Don't tread on me."

Jones attracted such favorable attention during this enterprise that on his return he was made commander of the twelve-ton brig Providence and was employed for a time in carrying troops from Rhode Island to New York. Since he was by birth a citizen of Great Britain, which then insisted that "once a British subject always a British subject," the English cruisers made determined efforts to capture him. Many of the officers declared that if they could lay hands on the audacious freebooter, as they called him, they would hang him at the yard arm. But, before doing so, they had to catch him, and that proved a harder task than they suspected. He was chased many times and often fired into, but the Providence was always swift enough to show a clean pair of heels to her pursuers and Jones himself was such a fine sailor that he laughed at their efforts to take him prisoner.

[Pg 57]One of the cleverest exploits of Jones was performed in the autumn of 1776. He saw an American brig returning from the West Indies, heavily laden with supplies for Washington's army, which was badly in need of them. A British frigate was in hot pursuit of the American, which was straining every nerve to escape, but would not have been able to do so except for Jones, who ran in between the two, and, firing into the frigate, induced her to let the American go and chase him. Taking advantage of the chance thus offered, the brig got safely away and then Jones himself dodged away from the frigate, which thus lost both.

In the month of October, 1776, Jones was promoted to the rank of captain and ordered to cruise between Boston and the Delaware. I must tell you an anecdote which illustrates his wonderful seamanship.

Some weeks before he was made a captain, and while cruising off Bermuda, he saw five sail far to the windward and he beat up, doing so carefully and with the purpose of finding out whether there was a chance for him to strike an effective blow. He picked out what looked like a large merchant ship and gave chase. He gained fast, but to his dismay, when he was quite close, he discovered that instead of [Pg 58]a merchant ship he had almost run into a twenty-eight gun frigate of the enemy.

Finding he had caught a Tartar, Jones did the only thing left to him. He hauled off and put on every stitch of sail and the frigate did the same. She proved the better sailer, and, though she gained slowly, it was surely, and in the course of a few hours she had approached within musket shot of the brig's lee quarter. There seemed no possible escape for Jones, knowing which, he did a remarkable thing. He veered off until the frigate was almost astern, when he put about dead before the wind, with every yard of canvas set.

The Englishman was dumfounded by the daring manœuvre, which brought the American within pistol shot, for he did not fire a gun until Jones was beyond reach of his grape. The pursuit was continued hour after hour, but the brig was now at her best and finally left her pursuer hopelessly astern. When the Providence ran into Newport in October she had captured or destroyed fifteen prizes.

Jones's bold and skilful seamanship drew attention to him and he was now given command of the 24-gun ship Alfred, while Captain Hacker took charge of the Providence. The two vessels started on a cruise in company and some days later the Alfred fell in with [Pg 59]three British vessels, and, after a brisk action, captured them all. One proved to be a transport with 150 men and a large amount of supplies for Burgoyne's army, which was at that time organizing in Montreal for its notable campaign through New York, where it was captured by General Gates, at Saratoga.

This transport was so valuable that Jones, instead of putting a prize crew on board, determined to take her into port, and, if in danger of capture from pursuit, he meant to sink her. It began snowing the following night and the Providence and Alfred were obliged to separate.

Jones was making for Boston when he was discovered by the frigate that he had outwitted two months before, when the Providence narrowly escaped capture. Night was closing in and the frigate being to windward, her outlines were indistinct. Captain Jones ordered his prizes to steer southward and to pay no attention to the signals displayed on his own vessel. At midnight he hoisted a toplight and tacked to the west, knowing the others would continue to the southward as he had directed. The strategem was successful, for at daylight the frigate was pressing hard after the Alfred, while the prizes had disappeared. The Alfred eluded her enemy as before, [Pg 60]and, upon reaching Boston, Jones found his captives awaiting him.

An idea of the effectiveness of the privateers may be gained by the statement that during the year 1777 nearly 500 vessels were captured by them. By that time Paul Jones had proven himself to be the finest officer in the American Navy. He had every quality to make him such. No one could surpass him in seamanship. He was cool and daring and was animated by the highest patriotism for his adopted country. Such a man was sure to be heard of again, as Great Britain learned to her cost.

France had shown a strong liking for the American colonies from the first. No doubt this liking was influenced by her hatred of England, for the nations had been bitter rivals for years. We had sent several commissioners to Paris, and they did a good deal for our country. The commissioners had a heavy, single-decked frigate built in Holland, which was named the South Carolinian and was intended for Paul Jones, but some difficulties occurred and he was sent to sea in the 18-gun ship Ranger, which left Portsmouth, N.H., at the beginning of November. She was so poorly equipped that Jones complained, though he did not hesitate on that account.

On the way to Nantes, in France, the Ranger cap[Pg 61]tured two prizes, refitted at Brest, and in April, 1778, sailed for the British coast. Having made several captures, Captain Jones headed for the Isle of Man, his intention being to make a descent upon Whitehaven. A violent wind that night baffled him, and, hoping to prevent his presence in the section from being discovered, he kept his vessel disguised as a merchantman. Sailing hither and thither, generally capturing all vessels that he sighted, he finally turned across to the Irish coast and in the latter part of the month was off Carrickfergus, where he learned from some fishermen that the British sloop-of-war Drake was at anchor in the roads. Jones was exceedingly anxious to attack her, and planned a night surprise, but again the violent wind interfered and he was forced to give up the scheme, so well suited to his daring nature.

This brave man now set out to execute one of the most startling schemes that can be imagined. Whitehaven at that time was a city of 50,000 inhabitants and the harbor was filled with shipping. His plan was to sail in among the craft and burn them all. It seemed like the idea of a man bereft of his senses, but there was not the slightest hesitation on his part. Such enterprises often succeed through their very boldness, and his belief was that by acting quickly he [Pg 62]could accomplish his purpose and strike a blow at England that would carry consternation to the people and the government.

Captain Jones had in mind the many outrages committed by British vessels along our seacoast, for, describing his purpose in a memorial to Congress, he said his intention was, by one good fire in England of British shipping, "to put an end to all burnings in America."

Paul Jones waited until midnight. Then, when no one was dreaming of danger, his men silently pulled away from the Ranger in two boats, one commanded by himself and the other by Lieutenant Wallingford. It was a long pull, and when they reached the outer pier of the harbor it was beginning to grow light in the east. They now parted company, and Jones directed his men to row for the south side of the harbor, while the Lieutenant was to make for the north shore. The object of the two was the same: the burning of the shipping.

Wallingford reached the north side, and then, strangely enough, gave up the attempt, his reason being that the candle on which he counted to start the fire was blown out. The reader must remember that in those days matches were unknown and the task of relighting had to be done with the steel, flint and tinder. Though the contrivance is an awkward one, we cannot help thinking the excuse of the Lieutenant was [Pg 64]weak, but the result was a failure on his part to carry out the important work assigned to him.

Captain Jones was a different kind of man. Although day had fully dawned, he kept his men rowing rapidly. Reaching the south side of the harbor, he came upon a small fort garrisoned by a few soldiers. Leaping out of the boat, the American dashed forward, bounded over the walls and captured the sentinels before they knew their danger. The guns were spiked and the garrison made prisoners.

"Set fire to the shipping!" he commanded to his men, while he, with only a single companion, ran for a second fort some distance away and spiked the guns in that. Then he hurried back to the first fort and found to his surprise that the fire had not been started.

"The candles have given out," was the reply to his angry inquiry.

It being broad daylight, his men expected him to jump into the boat and order them to return with all haste to the ship; but, instead of doing so, he darted into one of the nearest houses, procured some tinder and candles and began himself the work of destruction. Fixing his attention upon a large vessel, he climbed quickly aboard and started a fire in her steerage. To help matters, he flung a barrel of tar over [Pg 65]the flames and in a few minutes they were roaring fiercely. It meant prodigious damage, for the vessel was surrounded by more than a hundred others, none of which could move, since they were aground and the tide was out.

As may be supposed, there was great excitement by that time. The alarm had been given. Men were running to and fro, and a number hurried toward the burning ship with the purpose of extinguishing the flames. All the Americans had entered the small boat and were impatiently awaiting their commander. Instead of joining them, Jones drew his pistol, and, standing alone in front of the crowd, kept them back until the fire burst out of the steerage and began running up the rigging. Backing slowly with drawn pistol, he stepped into the boat and told his men to row with might and main for the vessel.

The instant this was done the crowd rushed forward and by desperate efforts succeeded in putting out the blaze before it had done much damage. Then the forts attempted to fire on the Americans, but their guns were spiked. Some cannon on the ships were discharged at the boats, but their shots went wild. When the Ranger was reached Captain Jones made the discovery that one of his men was missing. The reason was clear. He was a deserter and had been [Pg 66]seen by his former comrades running from house to house and giving the alarm. Such was the narrow chance by which one of the most destructive conflagrations of British shipping was averted.

As may be supposed, this daring act caused alarm throughout England. Jones was denounced as a freebooter and pirate, and every effort was made to capture him. Had his enemies succeeded, little mercy would have been shown the dauntless hero.

England was very cruel to many of her American prisoners, and Captain Jones fixed upon a bold and novel plan for compelling her to show more mercy toward those unfortunate enough to fall into her power. It was to capture some prominent nobleman and hold him as a hostage for the better treatment of our countrymen. It must be remembered that Jones was cruising near his birthplace and when a sailor boy had become familiar with the Scottish and the English coasts. The Ranger was a fast vessel, and, as I have shown, Jones himself was a master of seamanship. It would seem, therefore, that all he had to do was to be alert, and it need not be said that he and his crew were vigilant at all times.

The Earl of Selkirk was a Scottish nobleman who had his country seat at the mouth of the Dee, and Jones made up his mind that he was just the man to [Pg 67]serve for a hostage. At any rate, he could not be put to a better use and certainly would not suspect the purpose of the American vessel which, as night was closing in, anchored offshore. Indeed, no one dreamed that the vessel was the terrible American "pirate," which had thrown the whole country into terror.

Fortunately the night was dark and the men rowed to land without being noticed. The task was an easy one, for there was no one to resist them. They walked silently through the darkness to the fine grounds, and, having surrounded the handsome building, the officer in charge of the party presented himself at the door and made known his startling errand. He was informed that the Earl was absent. A careful search revealed that such was the fact, and all the trouble of the Americans went for naught.

It was a keen disappointment and the party decided to compensate themselves so far as they could. The Earl was wealthy and the house contained a great deal of valuable silver plate. A quantity of this was carried to the Ranger.

Captain Jones was angered when he learned what had been done. He knew the Earl and Lady Selkirk well and personally liked them both. The singular scheme he had in mind was solely for the benefit of his adopted countrymen.

[Pg 68]"I am accused of being a pirate, robber and thief," he exclaimed, "and you are doing all you can to justify the charges. Every ounce of plate shall be returned."

He kept his word. The messengers who took back the silver carried a note from Captain Jones apologizing to Lady Selkirk for the misconduct of his men.

Now, if there was anything which Paul Jones loved it was to fight. It was simply diversion for him to capture merchantmen or vessels that could make only a weak resistance, and he longed to give the enemy a taste of his mettle. It may be said that his situation grew more dangerous with every hour. His presence was known and a score of cruisers were hunting for him.

The British sloop of war Drake, which the gale prevented him from attacking, was still at Carrickfergus, and Jones sailed thither in the hope of inducing her to come out and fight him. Being uncertain of his identity, the captain of the Drake sent an officer in a boat to learn the truth. Captain Jones suspected the errand and skilfully kept his broadsides turned away until the officer, determined to know his identity, went aboard. As soon as he stepped on deck he was made a prisoner and sent below.

Captain Jones reasoned that the captain of the [Pg 69]Drake would miss his officer after awhile and come out to learn what had become of him. He, therefore, headed toward the North Channel, the Drake following, with the tide against her and the wind unfavorable until the mid-channel was reached, when, to quote Maclay, Paul Jones "in plain view of three kingdoms, hove to, ran up the flag of the new Republic and awaited the enemy."

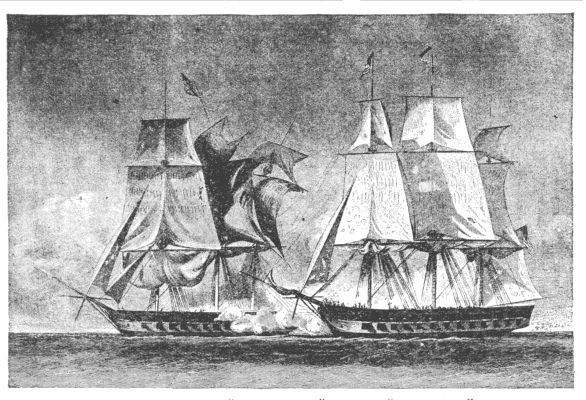

In reply to the demand of the Drake's captain, Jones gave the name of his vessel and expressed the pleasure it would give him to engage him in battle. The American was astern of the Drake, and, to show his earnestness, Captain Jones ordered his helm put up and let fly with a broadside. The Drake replied and then the battle was on. There was little manœuvring, the contest being what is known as a square yardarm and yardarm fight.

The comparative strength of the two vessels was as follows: The Ranger carried 18 guns and 123 men, the Drake 20 guns and 160 men, a number of the latter being volunteers for the fight, which lasted one hour and four minutes, at the end of which time the Ranger had lost two killed and six wounded and the Drake forty-two killed. The latter was so badly damaged by the well directed fire of the American that the captain called for quarter. Ceasing her fir[Pg 70]ing, Captain Jones lowered a boat and sent it to the Drake to take possession.

As an evidence of the effect of the fire of the Ranger, the following words may be quoted from Jones's official report: "Her fore and maintopsail yards being cut away and down on the caps, the topgallant yard and mizzen gaff both hanging up and down along the mast, the second ensign which they had hoisted shot away and hanging on the quarter gallery in the water, the jib shot away and hanging in the water, her sails and rigging cut entirely to pieces, her masts and yards all wounded and her hull very much galled."

The damages to the Ranger were so slight they were repaired by the close of the following day, when she got under sail with her prize. Despite the swarm of cruisers that were hunting for him, Jones passed unscathed through North Channel, along the western coast of Ireland and arrived at Brest, in France, within a month of the day he left the port, his cruise having been one of the most remarkable in naval history.

I have taken Paul Jones as the highest type of the infant American navy. There were others who fought with great bravery and did much to aid in the struggle for American independence, but none combined in such perfection the qualities of perfect seamanship, cool but dauntless courage and skill in fighting.

Of course, no matter how daring our cruisers, they did not always escape disaster. At the close of the Revolution there had been twenty-four vessels lost, carrying 470 guns. Several of these met their fate through shipwreck. Contrast with this the loss of Great Britain, which was 102 war vessels, carrying in all 2,624 guns. The total vessels of all kinds captured from the English by our cruisers and privateers was about 800.

Captain Jones had made so successful a cruise with the Ranger that he felt, upon returning to Brest, in France, he was entitled to a better ship. He wrote to Benjamin Franklin, expressing himself plainly on [Pg 72]that point, and the American commissioner, after several months' delay, had a ship of 40 guns placed under the command of Jones. Her original name was the Duras, but at Jones's request it was changed to the Bonhomme Richard. This was in compliment to Franklin, who was often called "Poor Richard" by his admiring countrymen, because for many years he had published "Poor Richard's Almanac," filled with wise and witty sayings.

This ship was an old Indiaman, in which 42 guns were placed, and the final number of her crew was 304. The 32-gun frigate Alliance, Captain Landais, was put under the orders of Captain Jones and a third, the Pallas, was bought and armed with thirty guns. A merchant brig and a cutter were also added to the squadron. It was found very hard to man these vessels and any other captain than Jones would have given up the task as an impossible one. It seemed as if about every known nation in the world was represented and some of the men of the most desperate character. Maclay says in his "History of the American Navy" that the muster roll of the Bonhomme Richard showed that the men hailed from America, France, Italy, Ireland, Germany, Scotland, Sweden, Switzerland, England, Spain, India, Norway, Portugal, Fayal and Malasia, while there were [Pg 73]seven Maltese and the knight of the ship's galley was from Africa. The majority of the officers, however, were American.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.

This squadron sailed from L'Orient on June 19, 1779. Almost immediately trouble occurred. Captain Landais, without any show of reason, claimed that the command, by right of seniority of commission, belonged to him. On the first night out the [Pg 74]Alliance and Bonhomme Richard collided and were obliged to return to port for repairs. Vexatious delays prevented the sailing of the squadron until August 14.