| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |

CHAPTER V—ELAM AND BABYLON, THE COUNTRY OF THE SEA AND THE KASSITES

CHAPTER VI—EARLY BABYLONIAN LIFE AND CUSTOMS

230.jpg Clay Tablet, Found at Susa, Bearing An Inscription in the Early Proto-elamite Character.

233.jpg Block of Limestone, Found at Susa, Bearing Inscriptions of Karibu-sha-shushinak.

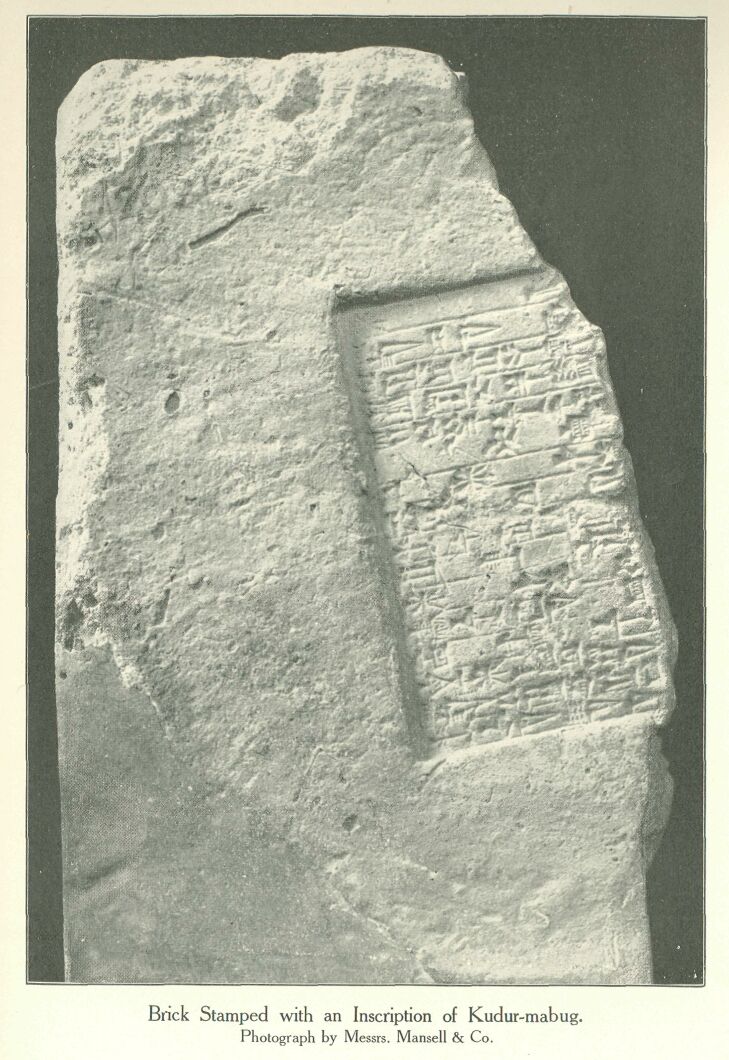

240.jpg Brick Stamped With an Inscription Of Kudur-maburg

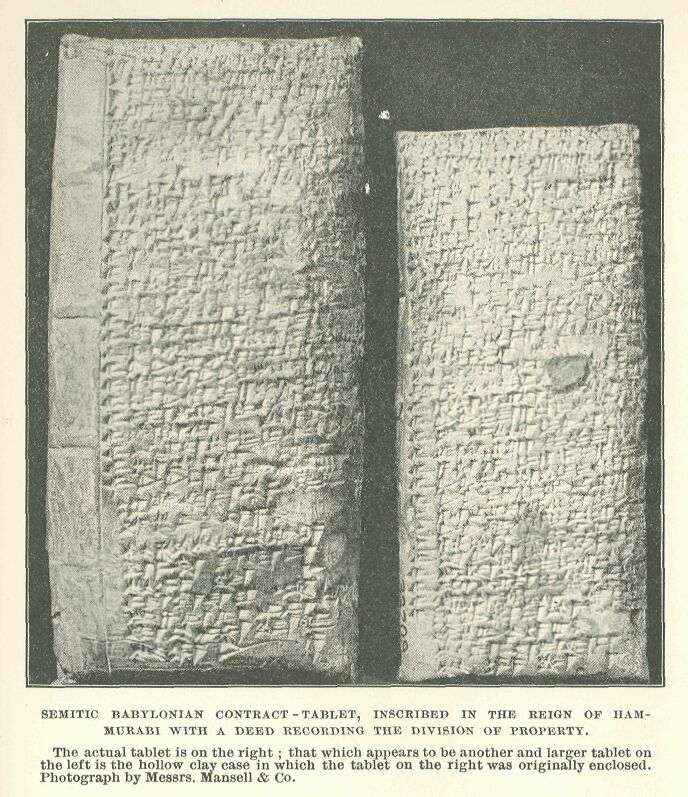

245.jpg Semitic Babylonian Contract-tablet

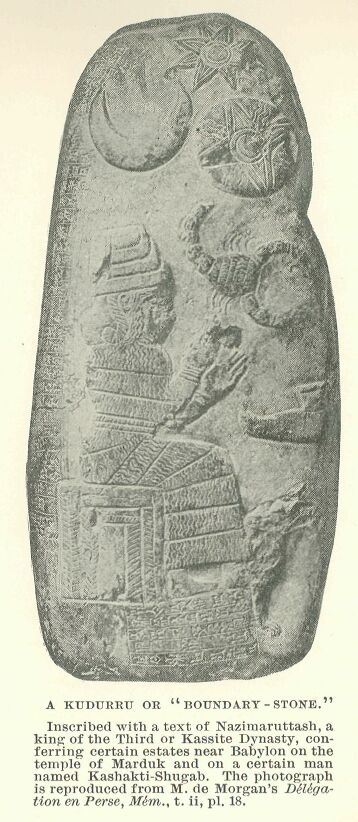

256.jpg a Kudurru Or "boundary-stone."

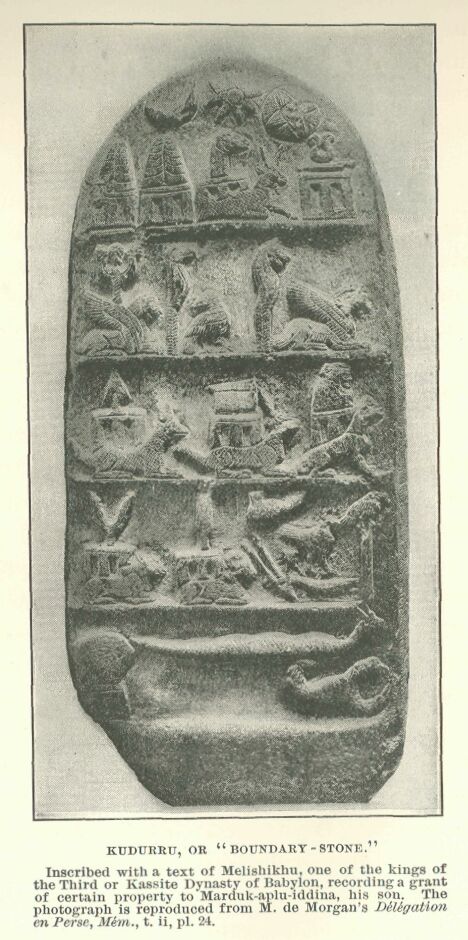

260.jpg Kuottrru, Or "boundary-stone."

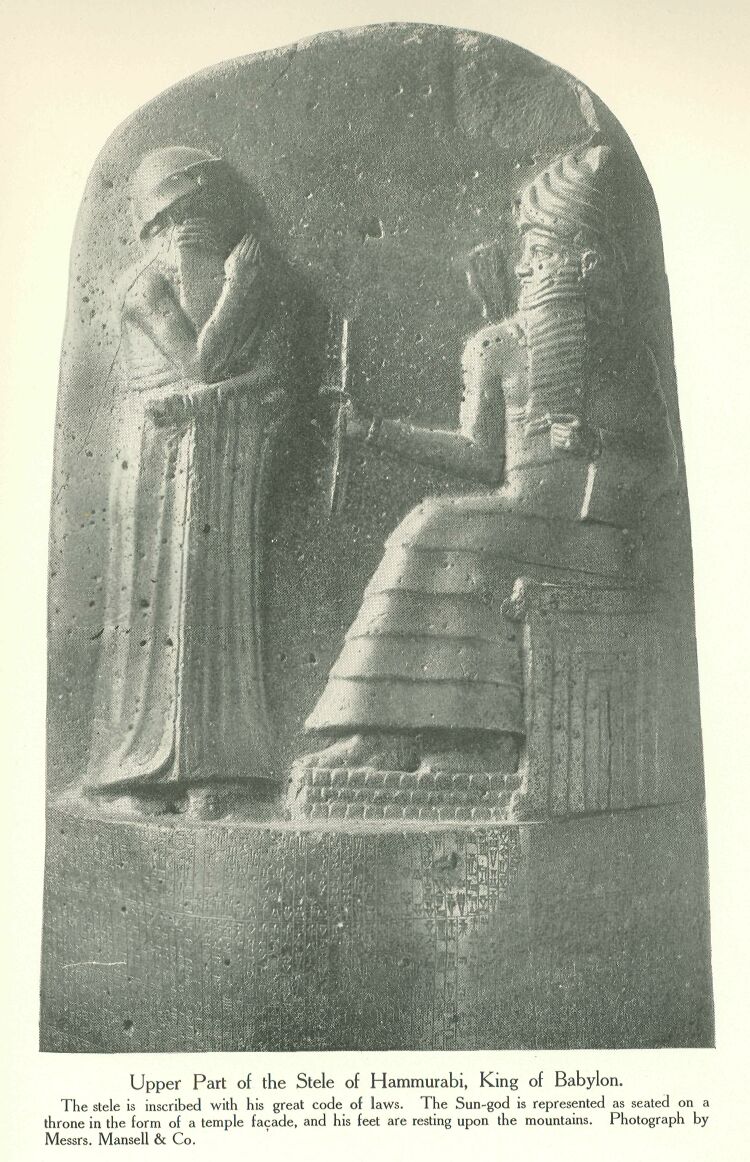

264a.jpg Upper Part of the Stele Of Hammurabi, King Of Babylon.

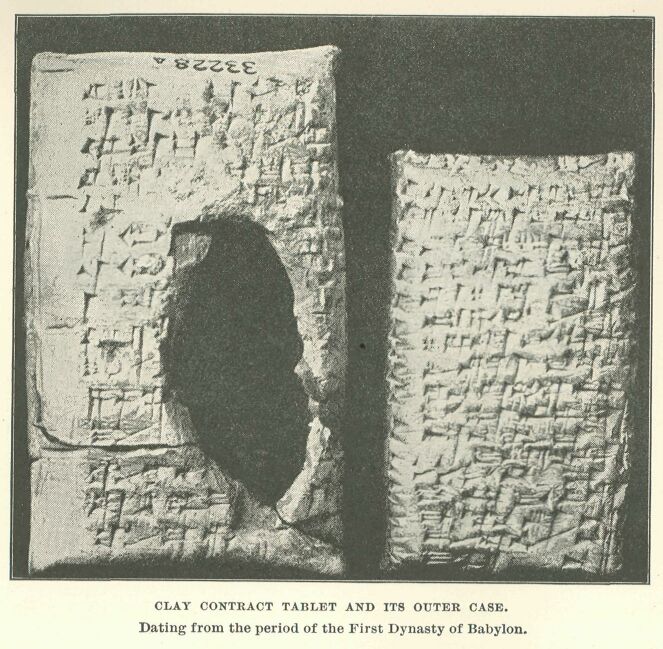

280.jpg Clay Contract Tablet and Its Outer Case

282.jpg a Track in the Desert.

283.jpg a Camping-ground in the Desert, Between Birejik And Urfa.

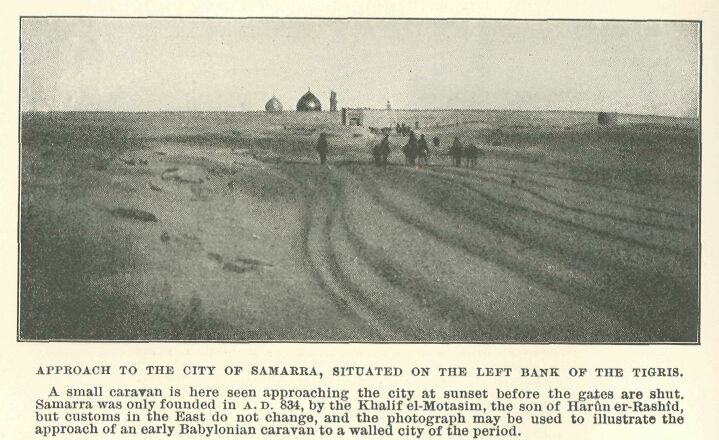

284.jpg Approach to the City of Samarra, Situated on The Left Bank of the Tigris.

285.jpg a Small Caravan in the Mountains of Kurdistan.

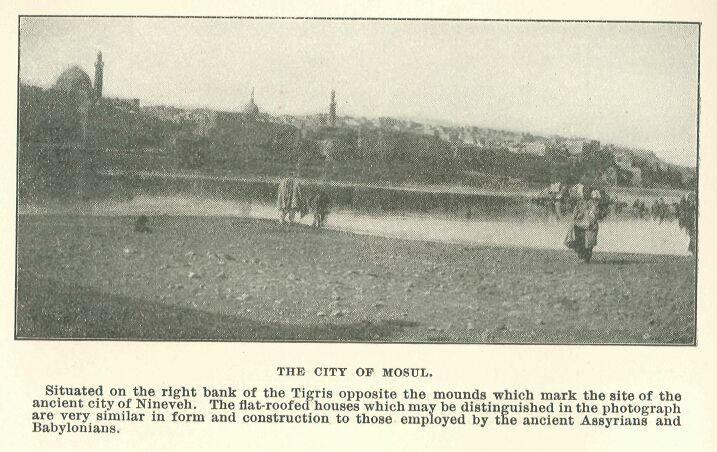

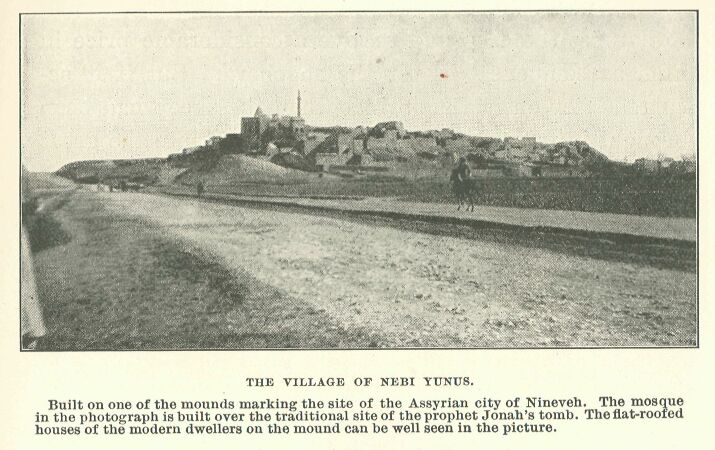

287.jpg the Village of Nebi Yunus.

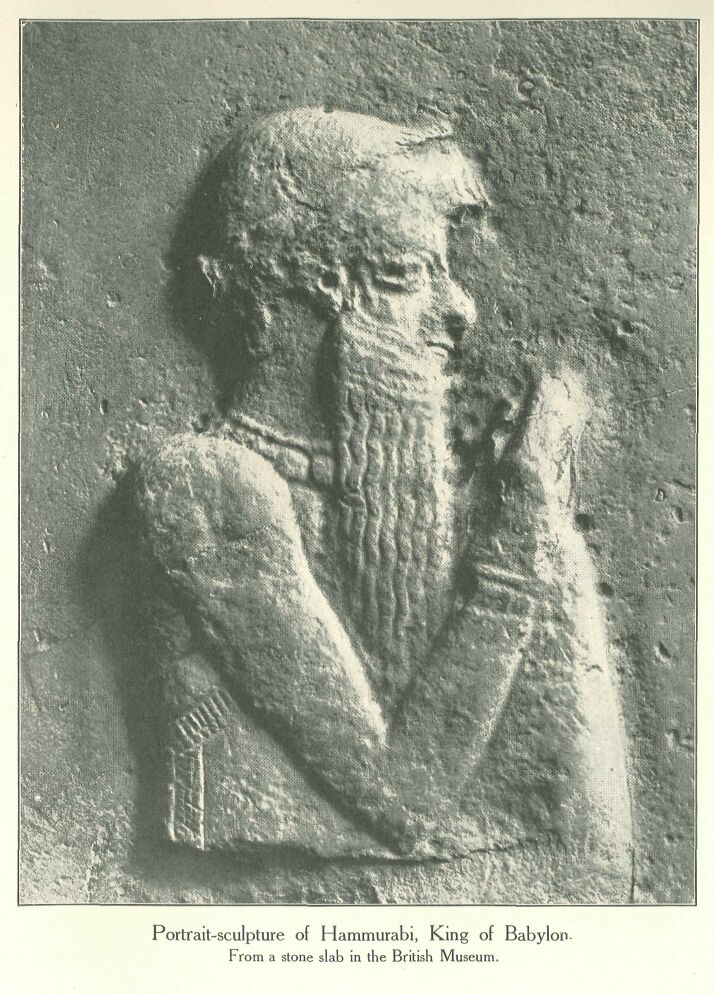

288.jpg Portrait-sculpture of Hammurabi, King Of Babylon

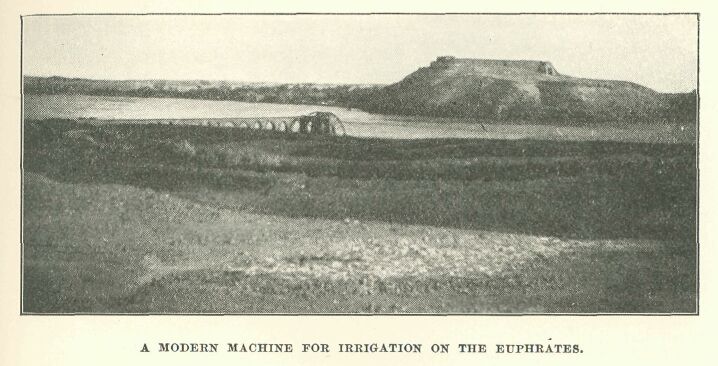

293.jpg a Modern Machine for Irrigation on The Euphrates.

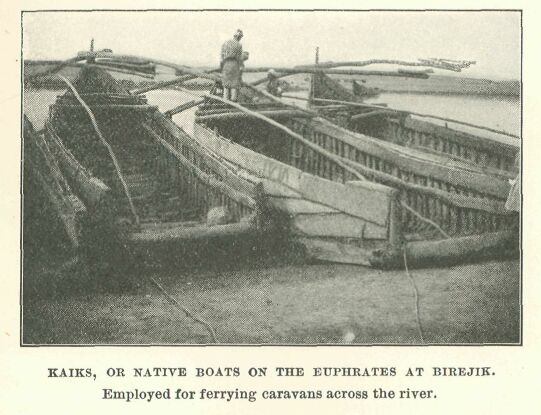

297.jpg Kaiks, Or Native Boats on the Euphrates At Birejie.

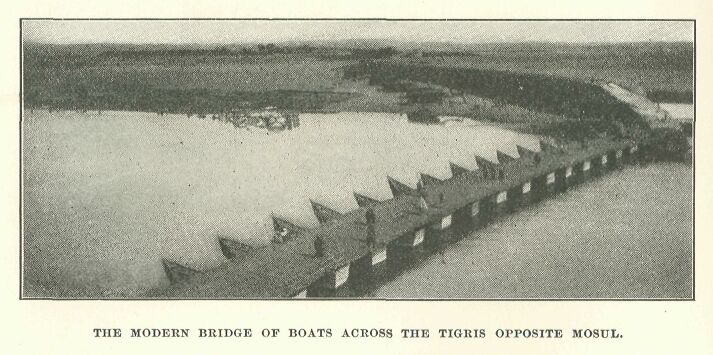

298.jpg the Modern Bridge of Boats Across The Tigris Opposite Mosul.

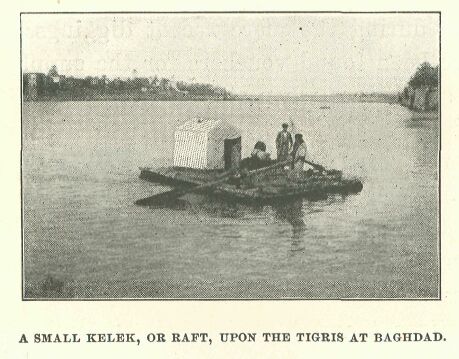

299.jpg a Small Kelek, or Raft, Upon the Tigris At Baghdad.

Up to five years ago our knowledge of Elam and of the part she played in the ancient world was derived, in the main, from a few allusions to the country to be found in the records of Babylonian and Assyrian kings. It is true that a few inscriptions of the native rulers had been found in Persia, but they belonged to the late periods of her history, and the majority consisted of short dedicatory formulae and did not supply us with much historical information. But the excavations carried on since then by M. de Morgan at Susa have revealed an entirely new chapter of ancient Oriental history, and have thrown a flood of light upon the position occupied by Elam among the early races of the East.

Lying to the north of the Persian Gulf and to the east of the Tigris, and rising from the broad plains nearer the coast to the mountainous districts within its borders on the east and north, Elam was one of the nearest neighbours of Chaldæa. A few facts concerning her relations with Babylonia during certain periods of her history have long been known, and her struggles with the later kings of Assyria are known in some detail; but for her history during the earliest periods we have had to trust mainly to conjecture. That in the earlier as in the later periods she should have been in constant antagonism with Babylonia might legitimately be suspected, and it is not surprising that we should find an echo of her early struggles with Chaldæa in the legends which were current in the later periods of Babylonian history. In the fourth and fifth tablets, or sections, of the great Babylonian epic which describes the exploits of the Babylonian hero Gilgamesh, a story is told of an expedition undertaken by Gilgamesh and his friend Ba-bani against an Elamite despot named Khum-baba. It is related in the poem that Khumbaba was feared by all who dwelt near him, for his roaring was like the storm, and any man perished who was rash enough to enter the cedar-wood in which he dwelt. But Gilgamesh, encouraged by a dream sent him by Sha-mash, the Sun-god, pressed on with his friend, and, having entered the wood, succeeded in slaying Khumbaba and in cutting off his head. This legend is doubtless based on episodes in early Babylonian and Elamite history. Khumbaba may not have been an actual historical ruler, but at least he represents or personifies the power of Elam, and the success of Gilgamesh no doubt reflects the aspirations with which many a Babylonian expedition set out for the Elamite frontier.

Incidentally it may be noted that the legend possibly had a still closer historical parallel, for the name of Khumbaba occurs as a component in a proper name upon one of the Elamite contracts found recently by M. de Morgan at Mai-Amir. The name in question is written Khumbaba-arad-ili, "Khumbaba, the servant of God," and it proves that at the date at which the contract was written (about 1300-1000 B.C.) the name of Khumbaba was still held in remembrance, possibly as that of an early historical ruler of the country.

In her struggles with Chaldæa, Elam was not successful during the earliest historical period of which we have obtained information; and, so far as we can tell at present, her princes long continued to own allegiance to the Semitic rulers whose influence was predominant from time to time in the plains of Lower Mesopotamia. Tradition relates that two of the earliest Semitic rulers whose names are known to us, Sargon and Narâm-Sin, kings of Agade, held sway in Elam, for in the "Omens" which were current in a later period concerning them, the former is credited with the conquest of the whole country, while of the latter it is related that he conquered Apirak, an Elamite district, and captured its king. Some doubts were formerly cast upon these traditions inasmuch as they were found in a text containing omens or forecasts, but these doubts were removed by the discovery of contemporary documents by which the later traditions were confirmed. Sargon's conquest of Elam, for instance, was proved to be historical by a reference to the event in a date-formula upon tablets belonging to his reign. Moreover, the event has received further confirmation from an unpublished tablet in the British Museum, containing a copy of the original chronicle from which the historical extracts in the "Omens" were derived. The portion of the composition inscribed upon this tablet does not contain the lines referring to Sargon's conquest of Elam, for these occurred in an earlier section of the composition; but the recovery of the tablet puts beyond a doubt the historical character of the traditions preserved upon the omen-tablet as a whole, and the conquest of Elam is thus confirmed by inference. The new text does recount the expedition undertaken by Narâm-Sin, the son of Sargon, against Apirak, and so furnishes a direct confirmation of this event.

Another early conqueror of Elam, who was probably of Semitic origin, was Alu-usharshid, king of the city of Kish, for, from a number of his inscriptions found near those of Sargon at Nippur in Babylonia, we learn that he subdued Elam and Para'se, the district in which the city of Susa was probably situated. From a small mace-head preserved in the British Museum we know of another conquest of Elam by a Semitic ruler of this early period. The mace-head was made and engraved by the orders of Mutabil, an early governor of the city of Dûr-ilu, to commemorate his own valour as the man "who smote the head of the hosts" of Elam. Mutabil was not himself an independent ruler, and his conquest of Elam must have been undertaken on behalf of the suzerain to whom he owed allegiance, and thus his victory cannot be classed in the same category as those of his predecessors. A similar remark applies to the success against the city of Anshan in Elam, achieved by Grudea, the Sumerian ruler of Shirpurla, inasmuch as he was a patesi, or viceroy, and not an independent king. Of greater duration was the influence exercised over Elam by the kings of Ur, for bricks and contract-tablets have been found at Susa proving that Dungi, one of the most powerful kings of Ur, and Bur-Sin, Ine-Sin, and Oamil-Sin, kings of the second dynasty in that city, all in turn included Elam within the limits of their empire.

Such are the main facts which until recently had been ascertained with regard to the influence of early Babylonian rulers in Elam. The information is obtained mainly from Babylonian sources, and until recently we have been unable to fill in any details of the picture from the Elamite side. But this inability has now been removed by M. de Morgan's discoveries. From the inscribed bricks, cones, stelæ, and statues that have been brought to light in the course of his excavations at Susa, we have recovered the name of a succession of native Elamite rulers. All those who are to be assigned to this early period, during which Elam owed allegiance to the kings of Babylonia, ascribe to themselves the title of patesi, or viceroy, of Susa, in acknowledgment of their dependence. Their records consist principally of building inscriptions and foundation memorials, and they commemorate the construction or repair of temples, the cutting of canals, and the like. They do not, therefore, throw much light upon the problems connected with the external history of Elam during this early period, but we obtain from them a glimpse of the internal administration of the country. We see a nation without ambition to extend its boundaries, and content, at any rate for the time, to owe allegiance to foreign rulers, while the energies of its native princes are devoted exclusively to the cultivation of the worship of the gods and to the amelioration of the conditions of the life of the people in their charge.

A difficult but interesting problem presents itself for solution at the outset of our inquiry into the history of this people as revealed by their lately recovered inscriptions,—the problem of their race and origin. Found at Susa in Elam, and inscribed by princes bearing purely Elamite names, we should expect these votive and memorial texts to be written entirely in the Elamite language. But such is not the case, for many of them are written in good Semitic Babylonian. While some are entirely composed in the tongue which we term Elamite or Anzanite, others, so far as their language and style is concerned, might have been written by any early Semitic king ruling in Babylonia. Why did early princes of Susa make this use of the Babylonian tongue?

At first sight it might seem possible to trace a parallel in the use of the Babylonian language by kings and officials in Egypt and Syria during the fifteenth century B.C., as revealed in the letters from Tell el-Amarna. But a moment's thought will show that the cases are not similar. The Egyptian or Syrian scribe employed Babylonian as a medium for his official foreign correspondence because Babylonian at that period was the lingua franca of the East. But the object of the early Elamite rulers was totally different. Their inscribed bricks and memorial stelæ were not intended for the eyes of foreigners, but for those of their own descendants. Built into the structure of a temple, or buried beneath the edifice, one of their principal objects was to preserve the name and deeds of the writer from oblivion. Like similar documents found on the sites of Assyrian and Babylonian cities, they sometimes include curses upon any impious man, who, on finding the inscription after the temple shall have fallen into ruins, should in any way injure the inscription or deface the writer's name. It will be obvious that the writers of these inscriptions intended that they should be intelligible to those who might come across them in the future. If, therefore, they employed the Babylonian as well as the Elamite language, it is clear that they expected that their future readers might be either Babylonian or Elamite; and this belief can only be explained on the supposition that their own subjects were of mixed race.

It is therefore certain that at this early period of Elamite history Semitic Babylonians and Elamites dwelt side by side in Susa and retained their separate languages. The problem therefore resolves itself into the inquiry: which of these two peoples occupied the country first? Were the Semites at first in sole possession, which was afterwards disputed by the incursion of Elamite tribes from the north and east? Or were the Elamites the original inhabitants of the land, into which the Semites subsequently pressed from Babylonia?

A similar mixture of races is met with in Babylonia itself in the early period of the history of that country. There the early Sumerian inhabitants were gradually dispossessed by the invading Semite, who adopted the civilization of the conquered race, and took over the system of cuneiform writing, which he modified to suit his own language. In Babylonia the Semites eventually predominated and the Sumerians as a race disappeared, but during the process of absorption the two languages were employed indiscriminately. The kings of the First Babylonian Dynasty wrote their votive inscriptions sometimes in Sumerian, sometimes in Semitic Babylonian; at other times they employed both languages for the same text, writing the record first in Sumerian and afterwards appending a Semitic translation by the side; and in the legal and commercial documents of the period the old Sumerian legal forms and phrases were retained intact. In Elam we may suppose that the use of the Sumerian and Semitic languages was the same.

It may be surmised, however, that the first Semitic incursions into Elam took place at a much later period than those into Babylonia, and under very different conditions. When overrunning the plains and cities of the Sumerians, the Semites were comparatively uncivilized, and, so far as we know, without a system of writing of their own. The incursions into Elam must have taken place under the great Semitic conquerors, such as Sar-gon and Narâm-Sin and Alu-usharshid. At this period they had fully adopted and modified the Sumerian characters to express their own Semitic tongue, and on their invasion of Elam they brought their system of writing with them. The native princes of Elam, whom they conquered, adopted it in turn for many of their votive texts and inscribed monuments when they wished to write them in the Babylonian language.

Such is the most probable explanation of the occurrence in Elam of inscriptions in the Old Babylonian language, written by native princes concerning purely domestic matters. But a further question now suggests itself. Assuming that this was the order in which events took place, are we to suppose that the first Semitic invaders of Elam found there a native population in a totally undeveloped stage of civilization? Or did they find a population enjoying a comparatively high state of culture, different from their own, which they proceeded to modify and transform! Luckily, we have not to fall back on conjecture for an answer to these questions, for a recent discovery at Susa has furnished material from which it is possible to reconstruct in outline the state of culture of these early Elamites.

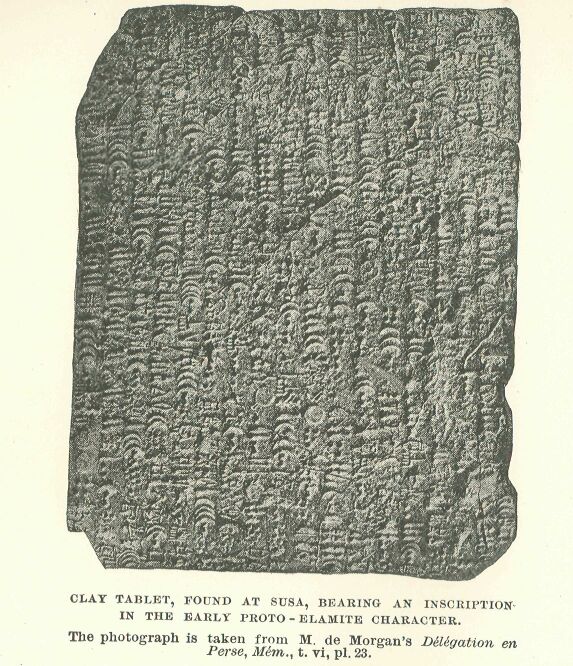

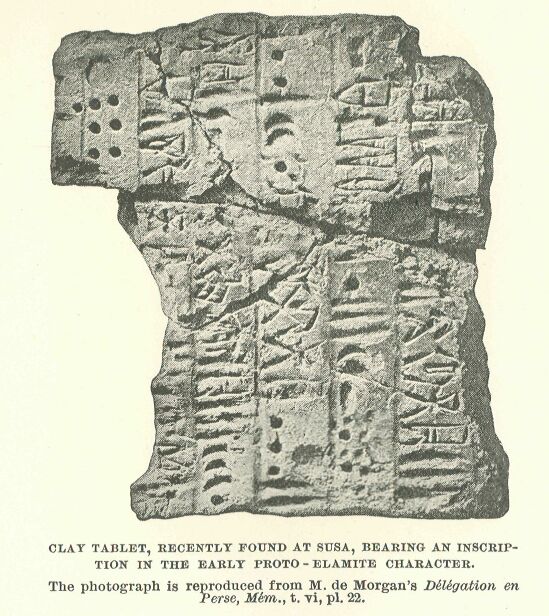

This interesting discovery consists of a number of clay tablets inscribed in the proto-Elamite system of writing, a system which was probably the only one in use in the country during the period before the Semitic invasion. The documents in question are small, roughly formed tablets of clay very similar to those employed in the early periods of Babylonian history, but the signs and characters impressed upon them offer the greatest contrast to the Sumerian and early Babylonian characters with which we are familiar. Although they cannot be fully deciphered at present, it is probable that they are tablets of accounts, the signs upon them consisting of lists of figures and what are probably ideographs for things. Some of the ideographs, such as that for "tablet," with which many of the texts begin, are very similar to the Sumerian or Babylonian signs for the same objects; but the majority are entirely different and have been formed and developed upon a system of their own.

The photograph is taken from M. de Morgan's Délégation en

Perse, Mem., t. vi, pi. 23.

On these tablets, in fact, we have a new class of cuneiform writing in an early stage of its development, when the hieroglyphic or pictorial character of the ideographs was still prominent.

The photograph is reproduced from M. de Morgan's Délégation

en Perse, Mém., t. vi, pi. 22.

Although the meaning of the majority of these ideographs has not yet been identified, Père Scheil, who has edited the texts, has succeeded in making out the system of numeration. He has identified the signs for unity, 10, 100, and 1,000, and for certain fractions, and the signs for these figures are quite different from those employed by the Sumerians.

The system, too, is different, for it is a decimal, and not a sexagesimal, system of numeration.

That in its origin this form of writing had some connection with that employed and, so far as we know, invented by the ancient Sumerians is possible.* But it shows small trace of Sumerian influence, and the disparity in the two systems of numeration is a clear indication that, at any rate, it broke off and was isolated from the latter at a very early period. Having once been adopted by the early Elamites, it continued to be used by them for long periods with but small change or modification. Employed far from the centre of Sumerian civilization, its development was slow, and it seems to have remained in its ideographic state, while the system employed by the Sumerians, and adopted by the Semitic Babylonians, was developed along syllabic lines.

* It is, of course, also possible that the system of writing

had no connection in its origin with that of the Sumerians,

and was invented independently of the system employed in

Babylonia. In that case, the signs which resemble certain of

the Sumerian characters must have been adopted in a later

stage of its development. Though it would be rash to

dogmatize on the subject, the view that connects its origin

with the Sumerians appears on the whole to fit in best with

the evidence at present available.

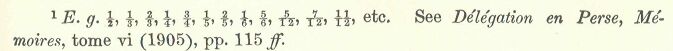

It was without doubt this proto-Elamite system of writing which the Semites from Babylonia found employed in Elam on their first incursions into that country. They brought with them their own more convenient form of writing, and, when the country had once been finally subdued, the subject Elamite princes adopted the foreign system of writing and language from their conquerors for memorial and monumental inscriptions. But the ancient native writing was not entirely ousted, and continued to be employed by the common people of Elam for the ordinary purposes of daily life. That this was the case at least until the reign of Karibu-sha-Shu-shinak, one of the early subject native rulers, is clear from one of his inscriptions engraved upon a block of limestone to commemorate the dedication of what were probably some temple furnishings in honour of the god Shu-shinak.

The photograph is taken from M. de Morgan's Délégation en

Perse, Mém., t. vi, pi. 2.

The main part of the inscription is written in Semitic Babylonian, and below there is an addition to the text written in proto-Elamite characters, probably enumerating the offerings which the Karibu-sha-Shushinak decreed should be made for the future in honour of the god.* In course of time this proto-Elamite system of writing by means of ideographs seems to have died out, and a modified form of the Babylonian system was adopted by the Elamites for writing their own language phonetically. It is in this phonetic character that the so-called "Anzanite" texts of the later Elamite princes were composed.

*We have assumed that both inscriptions were the work of

Karibu-sha-Shushinak. But it is also possible that the

second one in proto-Elamite characters was added at a later

period. From its position on the stone it is clear that it

was written after and not before Karibu-sha-Shushinak's

inscription in Semitic Babylonian. See the photographic

reproduction.

Karibu-sha-Shushinak, whose recently discovered bilingual inscription has been referred to above, was one of the earlier of the subject princes of Elam, and he probably reigned at Susa not later than B.C. 3000. He styles himself "patesi of Susa, governor of the land of Elam," but we do not know at present to what contemporary king in Babylonia he owed allegiance. The longest of his inscriptions that have been recovered is engraved upon a stele of limestone and records the building of the Gate of Shushinak at Susa and the cutting of a canal; it also recounts the offerings which Karibu-sha-Shushinak dedicated on the completion of the work. It may here be quoted as an example of the class of votive inscriptions from which the names of these early Elamite rulers have been recovered. The inscription runs as follows: "For the god Shushinak, his lord, Karibu-sha-Shushinak, the son of Shimbi-ish-khuk, patesi of Susa, governor of the land of Elam,—when he set the (door) of his Gate in place,... in the Gate of the god Shushinak, his lord, and when he had opened the canal of Sidur, he set up in face thereof his canopy, and he set planks of cedar-wood for its gate. A sheep in the interior thereof, and sheep without, he appointed (for sacrifice) to him each day. On days of festival he caused the people to sing songs in the Gate of the god Shushinak. And twenty measures of fine oil he dedicated to make his gate beautiful. Four magi of silver he dedicated; a censer of silver and gold he dedicated for a sweet odour; a,sword he dedicated; an axe with four blades he dedicated, and he dedicated silver in addition for the mounting thereof.... A righteous judgment he judged in the city! As for the man who shall transgress his judgment or shall remove his gift, may the gods Shushinak and Shamash, Bel and Ea, Ninni and Sin, Mnkharsag and Nati—may all the gods uproot his foundation, and his seed may they destroy!"

It will be seen that Karibu-sha-Shushinak takes a delight in enumerating the details of the offerings he has ordained in honour of his city-god Shushinak, and this religious temper is peculiarly characteristic of the princes of Elam throughout the whole course of their history. Another interesting point to notice in the inscription is that, although the writer invokes Shushinak, his own god, and puts his name at the head of the list of deities whose vengeance he implores upon the impious, he also calls upon the gods of the Babylonians. As he wrote the inscription itself in Babylonian, in the belief that it might be recovered by some future Semitic inhabitant of his country, so he included in his imprecations those deities whose names he conceived would be most reverenced by such a reader. In addition to Karibu-sha-Shushinak the names of a number of other patesis, or viceroys, have recently been recovered, such as Khutran-tepti, and Idadu I and his son Kal-Rukhu-ratir, and his grandson Idadu II. All these probably ruled after Karibu-sha-Shushinak, and may be set in the early period of Babylonian supremacy in Elam.

It has been stated above that the allegiance which these early Elamite princes owed to their overlords in Babylonia was probably reflected in the titles which they bear upon their inscriptions recently found at Susa. These titles are "patesi of Susa, shakkannak of Elam," which may be rendered as "viceroy of Susa, governor of Elam." But inscriptions have been found on the same site belonging to another series of rulers, to whom a different title is applied. Instead of referring to themselves as viceroys of Susa and governors of Elam, they bear the title of sukkal of Elam, of Siparki, and of Susa. Siparki, or Sipar, was probably the name of an important section of Elamite territory, and the title sukkalu, "ruler," probably carries with it an idea of independence of foreign control which is absent from the title of patesi. It is therefore legitimate to trace this change of title to a corresponding change in the political condition of Elam; and there is much to be said for the view that the rulers of Elam who bore the title of sukkalu reigned at a period when Elam herself was independent, and may possibly have exercised a suzerainty over the neighbouring districts of Babylonia.

The worker of this change in the political condition of Elam and the author of her independence was a king named Kutir-Nakhkhunte or Kutir-Na'khunde, whose name and deeds have been preserved in later Assyrian records, where he is termed Kudur-Nankhundi and Kudur-Nakhundu.* This ruler, according to the Assyrian king Ashur-bani-pal, was not content with throwing off the yoke under which his land had laboured for so long, but carried war into the country of his suzerain and marched through Babylonia devastating and despoiling the principal cities. This successful Elamite campaign took place, according to the computation of the later Assyrian scribes, about the year 2280 B. c, and it is probable that for many years afterwards the authority of the King of Elam extended over the plains of Babylonia. It has been suggested that Kutir-Nakh-khunte, after including Babylonia within his empire, did not remain permanently in Elam, but may have resided for a part of each year, at least, in Lower Mesopotamia. His object, no doubt, would have been to superintend in person the administration of his empire and to check any growing spirit of independence among his local governors. He may thus have appointed in Susa itself a local governor who would carry on the business of the country during his absence, and, under the king himself, would wield supreme authority. Such governors may have been the sukkali, who, unlike the patesi, were independent of foreign control, but yet did not enjoy the full title of "king."

* For references to the passages where the name occurs, see

King, Letters of Hammurabi, vol. i, p. Ivy.

It is possible that the sukkalu who ruled in Elam during the reign of Kutir-Nakhkhunte was named Temti-agun, for a short inscription of this ruler has been recovered, in which he records that he built and dedicated a certain temple with the object of ensuring the preservation of the life of Kutir-Na'khundi. If we may identify the Kutir-Va'khundi of this text with the great Elamite conqueror, Kutir-Nakhkhunte, it follows that Temti-agun, the sukkal of Susa, was his subordinate. The inscription mentions other names which are possibly those of rulers of this period, and reads as follows: "Temti-agun, sukkal of Susa, the son of the sister of Sirukdu', hath built a temple of bricks at Ishme-karab for the preservation of the life of Kutir-Na'khundi, and for the preservation of the life of Lila-irtash, and for the preservation of his own life, and for the preservation of the life of Temti-khisha-khanesh and of Pil-kishamma-khashduk." As Lila-irtash is mentioned immediately after Kutir-Na'khundi, he was possibly his son, and he may have succeeded him as ruler of the empire of Elam and Babylonia, though no confirmation of this view has yet been discovered. Temti-khisha-khanesh is mentioned immediately after the reference to the preservation of the life of Temti-agun himself, and it may be conjectured that the name was that of Temti-agun's son, or possibly that of his wife, in which event the last two personages mentioned in the text may have been the sons of Temti-agun.

This short text affords a good example of one class of votive inscriptions from which it is possible to recover the names of Elamite rulers of this period, and it illustrates the uncertainty which at present attaches to the identification of the names themselves and the order in which they are to be arranged. Such uncertainty necessarily exists when only a few texts have been recovered, and it will disappear with the discovery of additional monuments by which the results already arrived at may be checked. We need not here enumerate all the names of the later Elamite rulers which have been found in the numerous votive inscriptions recovered during the recent excavations at Susa. The order in which they should be arranged is still a matter of considerable uncertainty, and the facts recorded by them in such inscriptions as we possess mainly concern the building and restoration of Elamite temples and the decoration of shrines, and they are thus of no great historical interest. These votive texts are well illustrated by a remarkable find of foundation deposits made last year by M. de Morgan in the temple of Shushinak at Susa, consisting of figures and jewelry of gold and silver, and objects of lead, bronze, iron, stone, and ivory, cylinder-seals, mace-heads, vases, etc. This is the richest foundation deposit that has been recovered on any ancient site, and its archaeological interest in connection with the development of Elamite art is great. But in no other way does the find affect our conception of the history of the country, and we may therefore pass on to a consideration of such recent discoveries as throw new light upon the course of history in Western Asia.

With the advent of the First Dynasty in Babylon Elam found herself face to face with a power prepared to dispute her claims to exercise a suzerainty over the plains of Mesopotamia. It is held by many writers that the First Dynasty of Babylon was of Arab origin, and there is much to be said for this view. M. Pognon was the first to start the theory that its kings were not purely Babylonian, but were of either Arab or Aramaean extraction, and he based his theory on a study of the forms of the names which some of them bore. The name of Samsu-imna, for instance, means "the sun is our god," but the form of the words of which the name is composed betray foreign influence. Thus in Babylonian the name for "sun" or the Sun-god would be Shamash or Shamshu, not Samsu; in the second half of the name, while ilu ("god") is good Babylonian, the ending na, which is the pronominal suffix of the first person plural, is not Babylonian, but Arabic. We need not here enter into a long philological discussion, and the instance already cited may suffice to show in what way many of the names met in the Babylonian inscriptions of this period betray a foreign, and possibly an Arabic, origin. But whether we assign the forms of these names to Arabic influence or not, it may be regarded as certain that, the First Dynasty of Babylon had its origin in the incursion into Babylonia of a new wave of Semitic immigration.

The invading Semites brought with them fresh blood and unexhausted energy, and, finding many of their own race in scattered cities and settlements throughout the country, they succeeded in establishing a purely Semitic dynasty, with its capital at Babylon, and set about the task of freeing the country from any vestiges of foreign control. Many centuries earlier Semitic kings had ruled in Babylonian cities, and Semitic empires had been formed there. Sargon and Narâm-Sin, having their capital at Agade, had established their control over a considerable area of Western Asia and had held Elam as a province. But so far as Elam was concerned Kutir-Nakhkhunte had reversed the balance and had raised Elam to the position of the predominant power.

Of the struggles and campaigns of the earlier kings of the First Dynasty of Babylon we know little, for, although we possess a considerable number of legal and commercial documents of the period, we have recovered no strictly historical inscriptions. Our main source of information is the dates upon these documents, which are not dated by the years of the reigning king, but on a system adopted by the early Babylonian kings from their Sumerian predecessors. In the later periods of Babylonian history tablets were dated in the year of the king who was reigning at the time the document was drawn up, but this simple system had not been adopted at this early period. In place of this we find that each year was cited by the event of greatest importance which occurred in that year. This event might be the cutting of a canal, when the year in which this took place might be referred to as "the year in which the canal named Ai-khegallu was cut;" or it might be the building of a temple, as in the date-formula, "the year in which the great temple of the Moon-god was built;" or it might be "the conquest of a city, such as the year in which the city of Kish was destroyed." Now it will be obvious that this system of dating had many disadvantages. An event might be of great importance for one city, while it might never have been heard of in another district; thus it sometimes happened that the same event was not adopted throughout the whole country for designating a particular year, and the result was that different systems of dating were employed in different parts of Babylonia. Moreover, when a particular system had been in use for a considerable time, it required a very good memory to retain the order and period of the various events referred to in the date-formulae, so as to fix in a moment the date of a document by its mention of one of them. In order to assist themselves in their task of fixing dates in this manner, the scribes of the First Dynasty of Babylon drew up lists of the titles of the years, arranged in chronological order under the reigns of the kings to which they referred. Some of these lists have been recovered, and they are of the greatest assistance in fixing the chronology, while at the same time they furnish us with considerable information concerning the history of the period of which we should otherwise have been in ignorance.

From these lists of date-formulæ, and from the dates themselves which are found upon the legal and commercial tablets of the period, we learn that Kish, Ka-sallu, and Isin all gave trouble to the earlier kings of the First Dynasty, and had in turn to be subdued. Elam did not watch the diminution of her influence in Babylonia without a struggle to retain it. Under Kudur-mabug, who was prince or governor of the districts lying along the frontier of Elam, the Elamites struggled hard to maintain their position in Babylonia, making the city of Ur the centre from which they sought to check the growing power of Babylon. From bricks that have been recovered from Mukayyer, the site of the city of Ur, we learn that Kudur-mabug rebuilt the temple in that city dedicated to the Moon-god, which is an indication of the firm hold he had obtained upon the city. It was obvious to the new Semitic dynasty in Babylon that, until Ur and the neighbouring city of Larsam had been captured, they could entertain no hope of removing the Elamite yoke from Southern Babylonia. It is probable that the earlier kings of the dynasty made many attempts to capture them, with varying success. An echo of one of their struggles in which they claimed the victory may be seen in the date-formula for the fourteenth year of the reign of Sin-muballit, Hammurabi's father and predecessor on the throne of Babylon. This year was referred to in the documents of the period as "the year in which the people of Ur were slain with the sword." It will be noted that the capture of the city is not commemorated, so that we may infer that the slaughter of the Elamites which is recorded did not materially reduce their influence, as they were left in possession of their principal stronghold. In fact, Elam was not signally defeated in the reign of Kudur-mabug, but in that of his son Rim-Sin. From the date-formulæ of Hammurabi's reign we learn that the struggle between Elam and Babylon was brought to a climax in the thirtieth year of his reign, when it is recorded in the formulas that he defeated the Elamite army and overthrew Rim-Sin, while in the following year we gather that he added the land of E'mutbal, that is, the western district of Elam, to his dominions.

An unpublished chronicle in the British Museum gives us further details of Hammurabi's victory over the Elamites, and at the same time makes it clear that the defeat and overthrow of Rim-Sin was not so crushing as has hitherto been supposed. This chronicle relates that Hammurabi attacked Rim-Sin, and, after capturing the cities of Ur and Larsam, carried their spoil to Babylon. Up to the present it has been supposed that Hammurabi's victory marked the end of Elamite influence in Babylonia, and that thenceforward the supremacy of Babylon was established throughout the whole of the country. But from the new chronicle we gather that Hammurabi did not succeed in finally suppressing the attempts of Elam to regain her former position. It is true that the cities of Ur and Larsam were finally incorporated in the Babylonian empire, and the letters of Hammurabi to Sin-idinnam, the governor whom he placed in authority over Larsam, afford abundant evidence of the stringency of the administrative control which he established over Southern Babylonia. But Rîm-Sin was only crippled for the time, and, on being driven from Ur and Larsam, he retired beyond the Elamite frontier and devoted his energies to the recuperation of his forces against the time when he should feel himself strong enough again to make a bid for victory in his struggle against the growing power of Babylon. It is probable that he made no further attempt to renew the contest during the life of Hammurabi, but after Samsu-iluna, the son of Hammurabi, had succeeded to the Babylonian throne, he appeared in Babylonia at the head of the forces he had collected, and attempted to regain the cities and territory he had lost.

Inscribed in the reign of Hammurabi with a deed recording

the division of property. The actual tablet is on the right;

that which appears to be another and larger tablet on the

left is the hollow clay case in which the tablet on the

right was originally enclosed. Photograph by Messrs. Mansell

& Co.

The portion of the text of the chronicle relating to the war between Rîm-Sin and Samsu-iluna is broken so that it is not possible to follow the campaign in detail, but it appears that Samsu-iluna defeated Rim-Sin, and possibly captured him or burnt him alive in a palace in which he had taken refuge.

With the final defeat of Rîm-Sin by Samsu-iluna it is probable that Elam ceased to be a thorn in the side of the kings of Babylon and that she made no further attempts to extend her authority beyond her own frontiers. But no sooner had Samsu-iluna freed his country from all danger from this quarter than he found himself faced by a new foe, before whom the dynasty eventually succumbed. This fact we learn from the unpublished chronicle to which reference has already been made, and the name of this new foe, as supplied by the chronicle, will render it necessary to revise all current schemes of Babylonian chronology. Samsu-iluna's new foe was no other than Iluma-ilu, the first king of the Second Dynasty, and, so far from having been regarded as Samsu-iluna's contemporary, hitherto it has been imagined that he ascended the throne of Babylon one hundred and eighteen years after Samsu-iluna's death. The new information supplied by the chronicle thus proves two important facts: first, that the Second Dynasty, instead of immediately succeeding the First Dynasty, was partly contemporary with it; second, that during the period in which the two dynasties were contemporary they were at war with one another, the Second Dynasty gradually encroaching on the territory of the First Dynasty, until it eventually succeeded in capturing Babylon and in getting the whole of the country under its control. We also learn from the new chronicle that this Second Dynasty at first established itself in "the Country of the Sea," that is to say, the districts in the extreme south of Babylonia bordering on the Persian Gulf, and afterwards extended its borders northward until it gradually absorbed the whole of Babylonia. Before discussing the other facts supplied by the new chronicle, with regard to the rise and growth of the Country of the Sea, whose kings formed the so-called "Second Dynasty," it will be well to refer briefly to the sources from which the information on the period to be found in the current histories is derived.

All the schemes of Babylonian chronology that have been suggested during the last twenty years have been based mainly on the great list of kings which is preserved in the British Museum. This document was drawn up in the Neo-Babylonian or Persian period, and when complete it gave a list of the names of all the Babylonian kings from the First Dynasty of Babylon down to the time in which it was written. The names of the kings are arranged in dynasties, and details are given as to the length of their reigns and the total number of years each dynasty lasted. The beginning of the list which gave the names of the First Dynasty is wanting, but the missing portion has been restored from a smaller document which gives a list of the kings of the First and Second Dynasties only. In the great list of kings the dynasties are arranged one after the other, and it was obvious that its compiler imagined that they succeeded one another in the order in which he arranged them. But when the total number of years the dynasties lasted is learned, we obtain dates for the first dynasties in the list which are too early to agree with other chronological information supplied by the historical inscriptions. The majority of writers have accepted the figures of the list of kings and have been content to ignore the discrepancies; others have sought to reconcile the available data by ingenious emendations of the figures given by the list and the historical inscriptions, or have omitted the Second Dynasty entirely from their calculations. The new chronicle, by showing that the First and Second Dynasties were partly contemporaneous, explains the discrepancies that have hitherto proved so puzzling.

It would be out of place here to enter into a detailed discussion of Babylonian chronology, and therefore we will confine ourselves to a brief description of the sequence of events as revealed by the new chronicle. According to the list of kings, Iluma-ilu's reign was a long one, lasting for sixty years, and the new chronicle gives no indication as to the period of his reign at which active hostilities with Babylon broke out. If the war occurred in the latter portion of his reign, it would follow that he had been for many years organizing the forces of the new state he had founded in the south of Babylonia before making serious encroachments in the north; and in that case the incessant campaigns carried on by Babylon against Blam in the reigns of Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna would have afforded him the opportunity of establishing a firm foothold in the Country of the Sea without the risk of Babylonian interference. If, on the other hand, it was in the earlier part of his reign that hostilities with Babylon broke out, we may suppose that, while Samsu-iluna was devoting all his energies to crush Bim-Sin, the Country of the Sea declared her independence of Babylonian control. In this case we may imagine Samsu-iluna hurrying south, on the conclusion of his Elamite campaign, to crush the newly formed state before it had had time to organize its forces for prolonged resistance.

Whichever of these alternatives eventually may prove to be correct, it is certain that Samsu-iluna took the initiative in Babylon's struggle with the Country of the Sea, and that his action was due either to her declaration of independence or to some daring act of aggression on the part of this small state which had hitherto appeared too insignificant to cause Babylon any serious trouble. The new chronicle tells us that Samsu-iluna undertook two expeditions against the Country of the Sea, both of which proved unsuccessful. In the first of these he penetrated to the very shores of the Persian Gulf, where a battle took place in which Samsu-iluna was defeated, and the bodies of many of the Babylonian soldiers were washed away by the sea. In the second campaign Iluma-ilu did not await Samsu-iluna's attack, but advanced to meet him, and again defeated the Babylonian army. In the reign of Abêshu', Samsu-iluna's son and successor, Iluma-ilu appears to have undertaken fresh acts of aggression against Babylon; and it was probably during one of his raids in Babylonian territory that Abêshu' attempted to crush the growing power of the Country of the Sea by the capture of its daring leader, Iluma-ilu himself. The new chronicle informs us that, with this object in view, Abêshu' dammed the river Tigris, hoping by this means to cut off Iluma-ilu and his army, but his stratagem did not succeed, and Iluma-ilu got back to his own territory in safety.

The new chronicle does not supply us with further details of the struggle between Babylon and the Country of the Sea, but we may conclude that all similar attempts on the part of the later kings of the First Dynasty to crush or restrain the power of the new state were useless. It is probable that from this time forward the kings of the First Dynasty accepted the independence of the Country of the Sea upon their southern border as an evil which they were powerless to prevent. They must have looked back with regret to the good times the country had enjoyed under the powerful sway of Hammurabi, whose victorious arms even their ancient foes, the Blamites, had been unable to withstand. But, although the chronicle does not recount the further successes achieved by the Country of the Sea, it records a fact which undoubtedly contributed to hasten the fall of Babylon and bring the First Dynasty to an end. It tells us that in the reign of Samsu-ditana, the last king of the First Dynasty, the men of the land of Khattu (the Hittites from Northern Syria) marched against him in order to conquer the land of Akkad; in other words, they marched down the Euphrates and invaded Northern Babylonia. The chronicle does not state how far the invasion was successful, but the appearance of a new enemy from the northwest must have divided the Babylonian forces and thus have reduced their power of resisting pressure from the Country of the Sea. Samsu-ditana may have succeeded in defeating the Hittites and in driving them from his country; but the fact that he was the last king of the First Dynasty proves that in his reign Babylon itself fell into the hands of the king of the Country of the Sea.

The question now arises, To what race did the people of the Country of the Sea belong? Did they represent an advance-guard of the Kassite tribes, who eventually succeeded in establishing themselves as the Third Dynasty in Babylon? Or were they the Elamites who, when driven from Ur and Larsam, retreated southwards and maintained their independence on the shores of the Persian Gulf? Or did they represent some fresh wave of Semitic immigration'? That they were not Kassites is proved by the new chronicle which relates how the Country of the Sea was conquered by the Kassites, and how the dynasty founded by Iluma-ilu thus came to an end. There is nothing to show that they were Elamites, and if the Country of the Sea had been colonized by fresh Semitic tribes, so far from opposing their kindred in Babylon, most probably they would have proved to them a source of additional strength and support. In fact, there are indications that the people of the Country of the Sea are to be referred to an older stock than the Elamites, the Semites, or the Kassites. In the dynasty of the Country of the Sea there is no doubt that we may trace the last successful struggle of the ancient Sumerians to retain possession of the land which they had held for so many centuries before the invading Semites had disputed its possession with them.

Evidence of the Sumerian origin of the kings of the Country of the Sea may be traced in the names which several of them bear. Ishkibal, Grulkishar, Peshgal-daramash, A-dara-kalama, Akur-ul-ana, and Melam-kur-kura, the names of some of them, are all good Sumerian names, and Shushshi, the brother of Ishkibal, may also be taken as a Sumerian name. It is true that the first three kings of the dynasty, Iluma-ilu, Itti-ili-nibi, and Damki-ilishu, and the last king of the dynasty, Ea-gamil, bear Semitic Babylonian names, but there is evidence that at least one of these is merely a Semitic rendering of a Sumerian equivalent. Iluma-ilu, the founder of the dynasty, has left inscriptions in which his name is written in its correct Sumerian form as Dingir-a-an, and the fact that he and some of his successors either bore Semitic names or appear in the late list of kings with their Sumerian names translated into Babylonian form may be easily explained by supposing that the population of the Country of the Sea was mixed and that the Sumerian and Semitic tongues were to a great extent employed indiscriminately. This supposition is not inconsistent with the suggestion that the dynasty of the Country of the Sea was Sumerian, and that under it the Sumerians once more became the predominant race in Babylonia.

The new chronicle also relates how the dynasty of the Country of the Sea succumbed in its turn before the incursions of the Kassites. We know that already under the First Dynasty the Kassite tribes had begun to make incursions into Babylonia, for the ninth year of Samsu-iluna was named in the date-formulae after a Kassite invasion, which, as it was commemorated in this manner by the Babylonians, was probably successfully repulsed. Such invasions must have taken place from time to time during the period of supremacy attained by the Country of the Sea, and it was undoubtedly with a view to stopping such incursions—for the future that Ea-gamil—the last king of the Second Dynasty, decided to invade Elam and conquer the mountainous districts in which the Kassite tribes had built their strongholds. This Elamite campaign of Ea-gamil is recorded by the new chronicle, which relates how he was defeated and driven from the country by Ulam-Buriash, the brother of Bitiliash the Kassite. Ulam-Buriash did not rest content with repelling Ea-gamil's invasion of his land, but pursued him across the border and succeeded in conquering the Country of the Sea and in establishing there his own administration. The gradual conquest of the whole of Babylonia by the Kassites no doubt followed the conquest of the Country of the Sea, for the chronicle relates how the process of subjugation, begun by Ulam-Buriash, was continued by his nephew Agum, and we know from the lists of kings that Ea-gamil was the last king of the dynasty founded by Iluma-ilu. In this fashion the Second Dynasty was brought to an end, and the Sumerian element in the mixed population of Babylonia did not again succeed in gaining control of the government of the country.

It will be noticed that the account of the earliest Kassite rulers of Babylonia which is given by the new chronicle does not exactly tally with the names of the kings of the Third Dynasty as found upon the list of kings. On this document the first king of the dynasty is named Gandash, with whom we may probably identify Ulam-Buriash, the Kassite conqueror of the Country of the Sea; the second king is Agum, and the third is Bitiliashi. According to the new chronicle Agum was the son of Bitiliashi, and it would be improbable that he should have ruled in Babylonia before his father. But this difficulty is removed by supposing that the two names were transposed by some copyist. The different names assigned to the founder of the Kassite dynasty may be due to the existence of variant traditions, or Ulam-Buriash may have assumed another name on his conquest of Babylonia, a practice which was usual with the later kings of Assyria when they occupied the Babylonian throne.

The information supplied by the new chronicle with regard to the relations of the first three dynasties to one another is of the greatest possible interest to the student of early Babylonian history. We see that the Semitic empire founded at Babylon by Sumu-abu, and consolidated by Hammurabi, was not established on so firm a basis as has hitherto been believed. The later kings of the dynasty, after Elam had been conquered, had to defend their empire from encroachments on the south, and they eventually succumbed before the onslaught of the Sumerian element, which still remained in the population of Babylonia and had rallied in the Country of the Sea. This dynasty in its turn succumbed before the invasion of the Kassites from the mountains in the western districts of Elam, and, although the city of Babylon retained her position as the capital of the country throughout these changes of government, she was the capital of rulers of different races, who successively fought for and obtained the control of the fertile plains of Mesopotamia.

It is probable that the Kassite kings of the Third Dynasty exercised authority not only over Babylonia but also over the greater part of Elam, for a number of inscriptions of Kassite kings of Babylonia have been found by M. de Morgan at Susa. These inscriptions consist of grants of land written on roughly shaped stone stelæ, a class which the Babylonians themselves called kudurru, while they have been frequently referred to by modern writers as "boundary-stones." This latter term is not very happily chosen, for it suggests that the actual monuments themselves were set up on the limits of a field or estate to mark its boundary. It is true that the inscription on a kudurru enumerates the exact position and size of the estate with which it is concerned, but the kudurru was never actually used to mark the boundary. It was preserved as a title-deed, in the house of the owner of the estate or possibly in the temple of his god, and formed his charter or title-deed to which he could appeal in case of any dispute arising as to his right of ownership. One of the kudurrus found by M. de Morgan records the grant of a number of estates near Babylon by Nazimaruttash, a king of the Third or Kassite Dynasty, to the god Marduk, that is to say they were assigned by the king to the service of E-sagila, the great temple of Marduk at Babylon.

All the crops and produce from the land were granted for the supply of the temple, which was to enjoy the property without the payment of any tax or tribute. The text also records the gift of considerable tracts of land in the same district to a private individual named Kashakti-Shugab, who was to enjoy a similar freedom from taxation so far as the lands bestowed upon him were concerned.

This freedom from taxation is specially enacted by the document in the words: "Whensoever in the days that are to come the ruler of the country, or one of the governors, or directors, or wardens of these districts, shall make any claim with regard to these estates, or shall attempt to impose the payment of a tithe or tax upon them, may all the great gods whose names are commemorated, or whose arms are portrayed, or whose dwelling-places are represented, on this stone, curse him with an evil curse and blot out his name!"

Incidentally, this curse illustrates one of the most striking characteristics of the kudurrus, or "boundary-stones," viz. the carved figures of gods and representations of their emblems, which all of them bare in addition to the texts inscribed upon them. At one time it was thought that these symbols were to be connected with the signs of the zodiac and various constellations and stars, and it was suggested that they might have been intended to represent the relative positions of the heavenly bodies at the time the document was drawn up. But this text of Nazimaruttash and other similar documents that have recently been discovered prove that the presence of the figures and emblems of the gods upon the stones is to be explained on another and far more simple theory. They were placed there as guardians of the property to which the kudurru referred, and it was believed that the carving of their figures or emblems upon the stone would ensure their intervention in case of any attempted infringement of the rights and privileges which it was the object of the document to commemorate and preserve. A photographic reproduction of one side of the kudurru of Nazi-maruttash is shown in the accompanying illustration. There will be seen a representation of Gula or Bau, the mother of the gods, who is portrayed as seated on her throne and wearing the four-horned head-dress and a long robe that reaches to her feet. In the field are emblems of the Sun-god, the Moon-god, Ishtar, and other deities, and the representation of divine emblems and dwelling-places is continued on another face of the stone round the corner towards which Grula is looking. The other two faces of the document are taken up with the inscription.

An interesting note is appended to the text inscribed upon the stone, beginning under the throne and feet of Marduk and continuing under the emblems of the gods upon the other side. This note relates the history of the document in the following words: "In those days Kashakti-Shugab, the son of Nusku-na'id, inscribed (this document) upon a memorial of clay, and he set it before his god. But in the reign of Marduk-aplu-iddina, king of hosts, the son of Melishikhu, King of Babylon, the wall fell upon this memorial and crushed it. Shu-khuli-Shugab, the son of Nibishiku, wrote a copy of the ancient text upon a new stone stele, and he set it (before the god)." It will be seen, therefore, that this actual stone that has been recovered was not the document drawn up in the reign of Nazimaruttash, but a copy made under Marduk-aplu-iddina, a later king of the Third Dynasty. The original deed was drawn up to preserve the rights of Kashakti-Shugab, who shared the grant of land with the temple of Marduk. His share was less than half that of the temple, but, as both were situated in the same district, he was careful to enumerate and describe the temple's share, to prevent any encroachment on his rights by the Babylonian priests.

It is probable that such grants of land were made to private individuals in return for special services which they had rendered to the king. Thus a broken kudurru among M. de Morgan's finds records the confirmation of a man's claims to certain property by Biti-liash II, the claims being based on a grant made to the man's ancestor by Kurigalzu for services rendered to the king during his war with Assyria. One of the finest specimens of this class of charters or title-deeds has been found at Susa, dating from the reign of Melishikhu, a king of the Third Dynasty. The document in question records a grant of certain property in the district of Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû, near the cities Agade and Dûr-Kurigalzu, made by Melishikhu to Marduk-aplu-iddina, his son, who succeeded him upon the throne of Babylon. The text first gives details with regard to the size and situation of the estates included in the grant of land, and it states the names of the high officials who were entrusted with the duty of measuring them. The remainder of the text defines and secures the privileges granted to Marduk-aplu-iddina together with the land, and, as it throws considerable light upon the system of land tenure at the period, an extract from it may here be translated:

"To prevent the encroachment on his land," the inscription runs, "thus hath he (i.e. the king) established his (Marduk-aplu-iddina's) charter. On his land taxes and tithes shall they not impose; ditches, limits, and boundaries shall they not displace; there shall be no plots, stratagems, or claims (with regard to his possession); for forced labour or public work for the prevention of floods, for the maintenance and repair of the royal canal under the protection of the towns of Bit-Sikkamidu and Damik-Adad, among the gangs levied in the towns of the district of Ninâ-Agade, they shall not call out the people of his estate; they are not liable to forced labour on the sluices of the royal canal, nor are they liable for building dams, nor for closing the canal, nor for digging out the bed thereof."

"A cultivator of his lands, whether hired or belonging to the estate, and the men who receive his instructions (i.e. his overseers) shall no governor of Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû cause to leave his lands, whether by the order of the king, or by the order of the governor, or by the order of whosoever may be at Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû. On wood, grass, straw, corn, and every other sort of crop, on his carts and yoke, on his ass and man-servant, shall they make no levy. During the scarcity of water in the canal running between the Bati-Anzanim canal and the canal of the royal district, on the waters of his ditch for irrigation shall they make no levy; from the ditch of his reservoir shall they not draw water, neither shall they divert (his water for) irrigation, and other land shall they not irrigate nor water therewith. The grass of his lands shall they not mow; the beasts belonging to the king or to a governor, which may be assigned to the district of Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû, shall they not drive within his boundary, nor shall they pasture them on his grass. He shall not be forced to build a road or a bridge, whether for the king, or for the governor who may be appointed in the district of Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû, neither shall he be liable for any new form of forced labour, which in the days that are to come a king, or a governor appointed in the district of Bît-Pir-Shadû-rabû, shall institute and exact, nor for forced labour long fallen into disuse which may be revived anew. To prevent encroachment on his land the king hath fixed the privileges of his domain, and that which appertaineth unto it, and all that he hath granted unto him; and in the presence of Shamash, and Marduk, and Anunitu, and the great gods of heaven and earth, he hath inscribed them upon a stone, and he hath left it as an everlasting memorial with regard to his estate."

The whole of the text is too long to quote, and it will suffice to note here that Melishikhu proceeds to appeal to future kings to respect the land and privileges which he has granted to his son, Marduk-aplu-iddina, even as he himself has respected similar grants made by his predecessors on the throne; and the text ends with some very vivid curses against any one, whatever his station, who should make any encroachments on the privileges granted to Marduk-aplu-iddina, or should alter or do any harm to the memorial-stone itself. The emblems of the gods whom Melishikhu invokes to avenge any infringement of his grant are sculptured upon one side of the stone, for, as has already been remarked, it was believed that by carving them upon the memorial-stone their help in guarding the stone itself and its enactments was assured.

From the portion of the text inscribed upon the stone which has just been translated it is seen that the owner of land in Babylonia in the period of the Kassite kings, unless he was granted special exemption, was liable to furnish forced labour for public works to the state or to his district, to furnish grazing and pasture for the flocks and herds of the king or governor, and to pay various taxes and tithes on his land, his water for irrigation, and his crops. From the numerous documents of the First Dynasty of Babylon that have been recovered and published within the last few years we know that similar customs were prevalent at that period, so that it is clear that the successive conquests to which the country was subjected, and the establishment of different dynasties of foreign kings at Babylon, did not to any appreciable extent affect the life and customs of the inhabitants of the country or even the general character of its government and administration. Some documents of a commercial and legal nature, inscribed upon clay tablets during the reigns of the Kassite kings of Babylon, have been found at Nippur, but they have not yet been published, and the information we possess concerning the life of the people in this period is obtained indirectly from kudurrus or boundary-stones, such as those of Nazimaruttash and Melishikhu which have been already described. Of documents relating to the life of the people under the rule of the kings of the Country of the Sea we have none, and, with the exception of the unpublished chronicle which has been described earlier in this chapter, our information for this period is confined to one or two short votive inscriptions. But the case is very different with regard to the reigns of the Semitic kings of the First Dynasty of Babylon. Thousands of tablets relating to legal and commercial transactions during this period have been recovered, and more recently a most valuable series of royal letters, written by Hammurabi and other kings of his dynasty, has been brought to light.

The stele is inscribed with his great code of laws. The Sun-

god is represented as seated on a throne in the form of a

temple façade, and his feet are resting upon the mountains.

Photograph by Messrs. Mansell & Co.

Moreover, the recently discovered code of laws drawn up by Hammurabi contains information of the greatest interest with regard to the conditions of life that were prevalent in Babylonia at that period. From these three sources it is possible to draw up a comparatively full account of early Babylonian life and customs.

In tracing the ancient history of Mesopotamia and the surrounding countries it is possible to construct a narrative which has the appearance of being comparatively full and complete. With regard to Babylonia it may be shown how dynasty succeeded dynasty, and for long periods together the names of the kings have been recovered and the order of their succession fixed with certainty. But the number and importance of the original documents on which this connected narration is based vary enormously for different periods. Gaps occur in our knowledge of the sequence of events, which with some ingenuity may be bridged over by means of the native lists of kings and the genealogies furnished by the historical inscriptions. On the other hand, as if to make up for such parsimony, the excavations have yielded a wealth of material for illustrating the conditions of early Babylonian life which prevailed in such periods. The most fortunate of these periods, so far as the recovery of its records is concerned, is undoubtedly the period of the Semitic kings of the First Dynasty of Babylon, and in particular the reign of its greatest ruler, Hammurabi. When M. Maspero wrote his history, thousands of clay tablets, inscribed with legal and commercial documents and dated in the reigns of these early kings, had already been recovered, and the information they furnished was duly summarized by him.* But since that time two other sources of information have been made available which have largely increased our knowledge of the constitution of the early Babylonian state, its system of administration, and the conditions of life of the various classes of the population.

* Most of these tablets are preserved in the British Museum.

The principal?works in which they have been published are

Cuneiform Texts in the British Museum (1896, etc.),

Strassmaier's Altbabylonischen Vertràge aus Warka, and

Meissner's Beitràge zum altbabylonischen Privatrecht. A

number of similar tablets of this period, preserved in the

Pennsylvania Museum, will shortly be published by Dr. Ranke.

One of these new sources of information consists of a remarkable series of royal letters, written by kings of the First Dynasty, which has been recovered and is now preserved in the British Museum. The letters were addressed to the governors and high officials of various great cities in Babylonia, and they contain the king's orders with regard to details of the administration of the country which had been brought to his notice. The range of subjects with which they deal is enormous, and there is scarcely one of them which does not add to our knowledge of the period.* The other new source of information is the great code of laws, drawn up by Hammurabi for the guidance of his people and defining the duties and privileges of all classes of his subjects, the discovery of which at Susa has been described in a previous chapter. The laws are engraved on a great stele of diorite in no less than forty-nine columns of writing, of which forty-four are preserved,* and at the head of the stele is sculptured a representation of the king receiving them from Shamash, the Sun-god.

* See King, Letters and Inscriptions of Hammurabi, 3 vols.

(1898-1900).

This code shows to what an extent the administration of law and justice had been developed in Babylonia in the time of the First Dynasty. From the contracts and letters of the period we already knew that regular judges and duly appointed courts of law were in existence, and the code itself was evidently intended by the king to give the royal sanction to a great body of legal decisions and enactments which already possessed the authority conferred by custom and tradition. The means by which such a code could have come into existence are illustrated by the system of procedure adopted in the courts at this period. After a case had been heard and judgment had been given, a summary of the case and of the evidence, together with the judgment, was drawn up and written out on tablets in due legal form and phraseology. A list of the witnesses was appended, and, after the tablet had been dated and sealed, it was stored away among the legal archives of the court, where it was ready for production in the event of any future appeal or case in which the recorded decision was involved. This procedure represents an advanced stage in the system of judicial administration, but the care which was taken for the preservation of the judgments given was evidently traditional, and would naturally give rise in course of time to the existence of a recognized code of laws.

Moreover, when once a judgment had been given and had been duly recorded it was irrevocable, and if any judge attempted to alter such a decision he was severely punished. For not only was he expelled from his judgment-seat, and debarred from exercising judicial functions in the future, but, if his judgment had involved the infliction of a penalty, he was obliged to pay twelve times the amount to the man he had condemned. Such an enactment must have occasionally given rise to hardship or injustice, but at least it must have had the effect of imbuing the judges with a sense of their responsibility and of instilling a respect for their decisions in the minds of the people. A further check upon injustice was provided by the custom of the elders of the city, who sat with the judge and assisted him in the carrying out of his duties; and it was always open to a man, if he believed that he could not get justice enforced, to make an appeal to the king. It is not our present purpose to give a technical discussion of the legal contents of the code, but rather to examine it with the object of ascertaining what light it throws upon ancient Babylonian life and customs, and the conditions under which the people lived.

The code gives a good deal of information with regard to the family life of the Babylonians, and, above all, proves the sanctity with which the marriage-tie was invested. The claims that were involved by marriage were not lightly undertaken. Any marriage, to be legally binding, had to be accompanied by a duly executed and attested marriage-contract. If a man had taken a woman to wife without having carried out this necessary preliminary, the woman was not regarded as his wife in the legal sense. On the other hand, when once such a marriage-contract had been drawn up, its inviolability was stringently secured. A case of proved adultery on the part of a man's wife was punished by the drowning of the guilty parties, though the husband of the woman, if he wished to save his wife, could do so by an appeal to the king. Similarly, death was the penalty for a man who ravished another man's betrothed wife while she was still living in her father's house, but in this case the girl's innocence and inexperience were taken into account, and no penalty was enforced against her and she was allowed to go free. Where the adultery of a wife was not proved, and only depended on the accusation of the husband, the woman could clear herself by swearing her own innocence; if, however, the accusation was not brought by the husband himself, but by others, the woman could clear herself by submitting to the ordeal by water; that is to say, she would plunge into the Euphrates; if the river carried her away and she were drowned, it was regarded as proof that the accusation was well founded; if, on the contrary, she survived and got safely to the bank, she was considered innocent and was forthwith allowed to return to her household completely vindicated.

It will have been seen that the duty of chastity on the part of a married woman was strictly enforced, but the husband's responsibility to properly maintain his wife was also recognized, and in the event of his desertion she could under certain circumstances become the wife of another man. Thus, if he left his city and fled from it of his own free will and deserted his wife, he could not reclaim her on his return, since he had not been forced to leave the city, but had done so because he hated it. This rule did not apply to the case of a man who was taken captive in battle. In such circumstances the wife's action was to be guided by the condition of her husband's affairs. If the captive husband possessed sufficient property on which his wife could be maintained during his captivity in a strange land, she had no reason nor excuse for seeking another marriage. If under these circumstances she became another man's wife, she was to be prosecuted at law, and, her action being the equivalent of adultery, she was to be drowned. But the case was regarded as altered if the captive husband had not sufficient means for the maintenance of his wife during his absence. The woman would then be thrown on her own resources, and if she became the wife of another man she incurred no blame. On the return of the captive he could reclaim his wife, but the children of the second marriage would remain with their own father. These regulations for the conduct of a woman, whose husband was captured in battle, give an intimate picture of the manner in which the constant wars of this early period affected the lives of those who took part in them.

Under the Babylonians at the period of the First Dynasty divorce was strictly regulated, though it was far easier for the man to obtain one than for the woman. If we may regard the copies of Sumerian laws, which have come down to us from the late Assyrian period, as parts of the code in use under the early Sumerians, we must conclude that at this earlier period the law was still more in favour of the husband, who could divorce his wife whenever he so desired, merely paying her half a mana as compensation. Under the Sumerians the wife could not obtain a divorce at all, and the penalty for denying her husband was death. These regulations were modified in favour of the woman in Hammurabi's code; for under its provisions, if a man divorced his wife or his concubine, he was obliged to make proper provision for her maintenance. Whether she were barren or had borne him children, he was obliged to return her marriage portion; and in the latter case she had the custody of the children, for whose maintenance and education he was obliged to furnish the necessary supplies. Moreover, at the man's death she and her children would inherit a share of his property. When there had been no marriage portion, a sum was fixed which the husband was obliged to pay to his divorced wife, according to his status. In cases where the wife was proved to have wasted her household and to have entirely failed in her duty, her husband could divorce her without paying any compensation, or could make her a slave in his house, and the extreme penalty for this offence was death. On the other hand, a woman could not be divorced because she had contracted a permanent disease; and, if she desired to divorce her husband and could prove that her past life had been seemly, she could do so, returning to her father's house and taking her marriage portion with her.

It is not necessary here to go very minutely into the regulations given by the code with regard to marriage portions, the rights of widows, the laws of inheritance, and the laws regulating the adoption and maintenance of children. The customs that already have been described with regard to marriage and divorce may serve to indicate the spirit in which the code is drawn up and the recognized status occupied by the wife in the Babylonian household. The extremely independent position enjoyed by women in the early Babylonian days is illustrated by the existence of a special class of women, to which constant reference is made in the contracts and letters of the period. When the existence of this class of women was first recognized from the references to them in the contract-tablets inscribed at the time of the First Dynasty, they were regarded as priestesses, but the regulations concerning them which occur in the code of Hammurabi prove that their duties were not strictly sacerdotal, but that they occupied the position of votaries. The majority of those referred to in the inscriptions of this period were vowed to the service of E-bab-bara, the temple of the Sun-god at Sippara, and of E-sagila, the great temple of Marduk at Babylon, but it is probable that all the great temples in the country had classes of female votaries attached to them. From the evidence at present available it may be concluded that the functions of these women bore no resemblance to that of the sacred prostitutes devoted to the service of the goddess Ishtar in the city of Erech. They seem to have occupied a position of great influence and independence in the community, and their duties and privileges were defined and safeguarded by special legislation.