The Project Gutenberg EBook of Edge Hill, by Edwin Walford

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Edge Hill

The Battle and Battlefield

Author: Edwin Walford

Release Date: June 24, 2010 [EBook #32958]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EDGE HILL ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

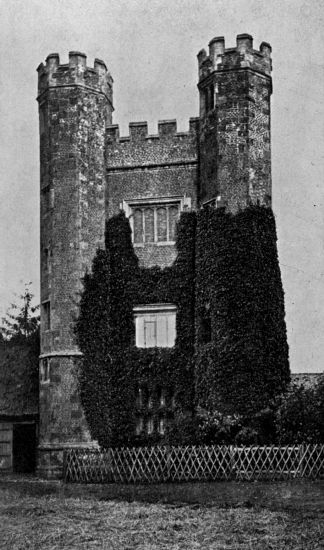

THE TOWER, EDGE HILL.

SECOND EDITION.

Banbury:

E. A. Walford, 71 & 72, High Street.

London:

Castle, Lamb & Storr, Salisbury Square.

1904.

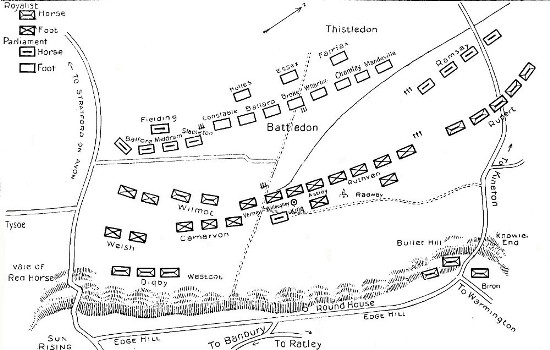

For the present edition the available material of the last eighteen years has been consulted, but the plans of battle are similar to two of those of my book of 1886. They were then the first series of diagrammatic representations of the fight published, but in no case has this been acknowledged in the many plans of like kind subsequently published. Some new facts and inferences the author hopes may increase the value of the account.

The letters of Captain Nathaniel Fiennes and Captain Kightley, now added, may serve to make the tale a more living one. They are reproduced, by the kind courtesy of the authorities of the Radcliffe Library, Oxford, and the Birmingham Reference Library.

New pages of Notes on Banbury, and an extended bibliography are also given.

Edwin A. Walford.

Banbury,

March, 1904.

In the following pages an endeavour has been made to give a concise account of the physical features of the Edge Hill district, as well as to describe the events of the first great battle of the Civil War, with which it is so intimately associated. The intention is to provide a handbook for the guidance of the visitor rather than to attempt any elaborate historical or scientific work. Though Nugent’s “Memorials of John Hampden” has supplied the basis of the information, Clarendon’s “History of the Great Rebellion,” the various pamphlets of the time, and Beesley’s “History of Banbury,” have also been freely used. In order to avoid burdening the pages with foot notes, a catalogue of works upon the subject is printed as an appendix, and the letters and numbers throughout the text refer thereto. The catalogue, it is hoped, may be of use to the future student. The plans of the battle, based upon Nugent’s account, must be looked upon as merely diagrammatic, the scale being unavoidably distorted for the purpose of showing the conjectured positions of the troops. In the plans it may be worth note that the troops then known as “dragooners” are classed with the infantry.

The “Notes on Banbury and Thereabouts” are in part reproduced from a small pamphlet published in 1879. Much of the detail relating to the older buildings has been derived from Skelton’s “Antiquities of Oxfordshire” and Parker’s descriptions in Beesley’s History.

To Mr. W. L. Whitehorn my thanks are due for aid in the revision of “Edge Hill,” and in the compilation of the “Notes.”

Edwin A. Walford.

Banbury,

July 7th, 1886.

o Edge Hill from Banbury a good road trends gradually up hill nearly the

whole way. It rises from the 300 foot level of the Cherwell Vale to 720 at

the highest ground of the ridge of the hill. At a distance of eight miles

to the North-West is the edge or escarpment of high ground bounded on the

East side by the vale of a tributary of the Cherwell, and on the North and

West by the plain drained by the tributaries of the Avon. From Warmington,

six miles from Banbury, North-Westwards to the point marked on the

Ordnance Map as Knowle End, and thence South-Westwards to the Sun Rising,

once the site of a hostelry on the Banbury and Stratford-on-Avon coach

road, the edge makes a right angle with the apex at Knowle End. The[Pg 2]

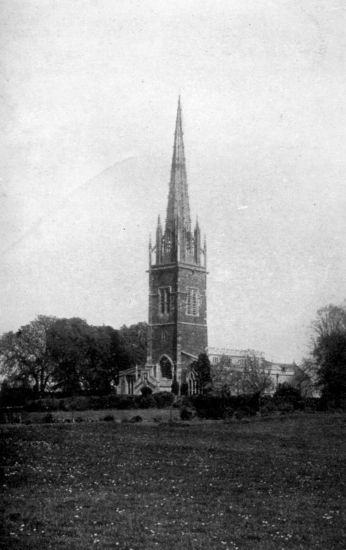

nearest point of the hill range is at Warmington, where a fine fourteenth

century Church stands high above the rock of the roadway. There is the

first record of the battle—a simple headstone to the right of the path to

the South porch telling how one Captain Alexander Gourdin had died on

October 24th, 1642, the day after the fight. From the church-yard long

flights of steps lead to the roadway and village below, where the house

tops show through the foliage of the apple orchards in which they are

partly hidden. Across the vale, three miles to the North, is the range of

the Burton Dassett Hills, an outlier of the Edge Hill range. The Windmill

Hill, the most distant, bears the Beacon House; the square tower of Burton

Dassett Church may be seen amongst the elms on the lower slopes of Church

Hill; Bitham Hill appears in the foreground of the range with the pretty

spire and village of Avon Dassett close at hand.

o Edge Hill from Banbury a good road trends gradually up hill nearly the

whole way. It rises from the 300 foot level of the Cherwell Vale to 720 at

the highest ground of the ridge of the hill. At a distance of eight miles

to the North-West is the edge or escarpment of high ground bounded on the

East side by the vale of a tributary of the Cherwell, and on the North and

West by the plain drained by the tributaries of the Avon. From Warmington,

six miles from Banbury, North-Westwards to the point marked on the

Ordnance Map as Knowle End, and thence South-Westwards to the Sun Rising,

once the site of a hostelry on the Banbury and Stratford-on-Avon coach

road, the edge makes a right angle with the apex at Knowle End. The[Pg 2]

nearest point of the hill range is at Warmington, where a fine fourteenth

century Church stands high above the rock of the roadway. There is the

first record of the battle—a simple headstone to the right of the path to

the South porch telling how one Captain Alexander Gourdin had died on

October 24th, 1642, the day after the fight. From the church-yard long

flights of steps lead to the roadway and village below, where the house

tops show through the foliage of the apple orchards in which they are

partly hidden. Across the vale, three miles to the North, is the range of

the Burton Dassett Hills, an outlier of the Edge Hill range. The Windmill

Hill, the most distant, bears the Beacon House; the square tower of Burton

Dassett Church may be seen amongst the elms on the lower slopes of Church

Hill; Bitham Hill appears in the foreground of the range with the pretty

spire and village of Avon Dassett close at hand.

Westward of Warmington Church runs Camp Lane. It winds along the ridge, and commands wide views of the plain lands. A beautiful field path springs from the South side of the lane leading through the village of Ratley to the Round House and Ratley Grange. Facing Southwards, one looks upon an equally pleasant[Pg 3] though more circumscribed view—the vale of Hornton. The Arlescot Woods clothe the Northern slopes, and the Manor House rests amongst the fine trees below. The terraced fields of Adsum Hollow are three miles down vale Southward, and Nadbury Camp, supposedly a Romano-british remain, is but a remnant of similar natural terracing on the South side of the Camp Lane above Arlescot.

At Knowle End, where the road to Kineton plunges steeply down hill, is the first point of the battle ground and the commencement, strictly speaking, of Edge Hill. A short distance down the Kineton Road, a pathway on the right leads under overspreading beech and oak trees for some distance along the crest of the Knoll, whence a good side view of the hill may be got. The gate on the opposite side of the Kineton Road opens to a path through the Radway Woods, and from it, where the foliage is less dense a prospect opens of many wide leagues of fair midland country—a veritable patchwork of field and hedgerow. The furze below covers in part Bullet Hill, the last stand of the Royalists on the battle ground. The road from Kineton as well as the footway through the woods leads to Edge Hill Tower, or Round House. Covering the steep hill sides are beech, elm, chestnut[Pg 4] and lime trees of exceptionally fine growth and a wealth of common wild flowers. The Tower or Round House is an inn, which, with a modern-antique ruin, makes as it were a landscape gardening adjunct to Radway Grange lying in the park below. From its upper room is obtained a fine view of the country. It is an octagonal tower, and was erected with artificial ruins in 1750 to mark the spot where the King’s Standard was displayed before the Royalist army descended into the plain to give battle. The village of Radway rests amongst the elms near the foot of the hill, the church spire being one of the prominent objects of the foreground. Kineton lies about four miles directly to the North, beyond which Warwick Castle may be sometimes descried, or the yet more distant spires of Coventry. Some distance from the Burton hills the smoke of the Harbury lime works drifts across the landscape. The farms Battledon and Thistledon, about midway between Radway and Kineton, marked by the coppices which almost hide the homesteads, are noted from the fact of so much of the fight having revolved round them.

The footway to the Sun Rising, 1½ miles S.W. of the Round House, follows the hill side, and though still pleasantly wooded, soon gets clear[Pg 5] of that heavy growth of foliage which has hitherto shut out so much of the view. The eye ranges over the flat Warwickshire plain in front, to the hills of Gloucestershire and Worcestershire on the West and the North-West. The North-Eastern outliers of the Cotteswolds, the hills of Ebrington and Ilmington, are the nearest in prominence Westwards, beyond which a clear day will allow even the distant slopes of the Malverns to be seen. The Bromsgrove, Clent and Clee hills fringe the North-West horizon, and sometimes the Wrekin is said to appear “like a thin cloud” far away.

At the point where the pathway enters the Stratford-on-Avon road stands Edge Hill House (the Sun Rising) wherein years ago were some curious relics of the fight: breast-plates, swords, matchlocks, and a sword supposed on the evidence of emblems in its decoration to have belonged to the Earl Lindsay, who commanded the royalists forces prior to the battle, and who received his death wound in the fight.

In a fir coppice about 200 or 300 yards to the South of the house, the figure of a red horse roughly cut in the turf of the hill side might formerly be seen. Dugdale[h] gives the following account of it: “Within the Precinct of that Manour in Tysoe, now belonging to the E. of[Pg 6] Northampton (but antiently to the Family of Stafford, as I have shewed) there is cut upon the side of Edg-Hill the Proportion of a Horse, in a very large Forme; which by Reason of the ruddy Colour of the Earth, is called The Red Horse, and gives Denomination to that fruitfull and pleasant Countrey thereabouts, commonly called The Vale of Red Horse. The Trenches of which Ground, where the Shape of the said Horse is so cut out, being yearly scoured by a Freeholder in this Lordship, who holds certain Lands there by that service.” There is a tradition quoted by Beesley[b] of its having been cut to commemorate the slaughter of a chieftain’s horse at the battle of Towton, in 1461, the chieftain preferring to share the perils of the fight with his followers.

he reign of King Charles I. showed a widening of the difference between

the ecclesiastic and puritan elements of the English community—elements

which were the centres of the subsequently enlarged sections, royalist and

parliamentarian. In the later dissentions between the King and the Commons

it was [Pg 7]early apparent how widespread had been the alienation of the

people from the King’s cause—an alienation heightened, as Green in his

“Short History” tells us, by a fear that the spirit of Roman Catholicism,

so victorious on the continent, should once more become dominant in

England. How great was the tension may be known from the fact of the

contemplated emigration to the American colonies of such leaders as Lord

Saye and Sele, Lord Warwick, Lord Brooke, and Sir John Hampden and Oliver

Cromwell. When the rupture at last came, the Parliament was found to have

secured the larger arsenals, and also to have forces at its disposal in

the trained bands of London and in the militia, which it was enabled

rapidly to enrol. Though the unfurling of the Royal Standard near

Nottingham failed to secure many adherents to the King’s cause, Essex

hesitated to attack the royalists when they might have been easily

dispersed, thinking no doubt to overawe the King by mere show of force.

Yet when Charles began recruiting in the neighbourhood of Shrewsbury, he

was soon able to gather an army, and on October 12th, 1642, he commenced

his march upon London. The astute and carefully moderate policy of the

Commons was to rescue the King from his surroundings, and to destroy[Pg 8] the

enemies, especially the foreign enemies, of the State, about the King’s

person. The sanctity of the King’s person was yet a prominent factor—the

belief in divinity of Kingship, notwithstanding all the misrule there had

been, was yet alive in the hearts of the people. Therefore when the King

had gathered his forces together and began his Southward march, Lord Essex

with his army was commissioned “to march against his Majesties Army and

fight with them, and to rescue the persons of the King, Prince and Duke of

York.” The Earl of Essex, with the Parliamentarian forces, was at that

time in Worcestershire, endeavouring to prevent the recruiting of the

King’s troops; and though the Earl moved two days later on by rapid

marches into Warwickshire, it was only to find that he had been

out-marched by the King, who, after resting at Southam, stood with the

Royalist army at Edgcot across the way to the capital. That this had been

accomplished, notwithstanding the opposition of the strongholds of Warwick

and Coventry, speaks not unfavourably for the generalship of Earl Lindsay,

the King’s Lieutenant-General, whom we find at Edgcot contemplating an

attack upon Banbury Castle. The King’s was a good position: it commanded

all the roads to London, held Banbury in its hand, [Pg 9]covered the Cherwell

bridge and fords, and had within touch the dominating escarpment of Edge

Hill. If the purpose was the subjection of some prominent leaders of the

Parliamentarians it succeeded only in the taking of Lord Saye and Sele’s

house at Broughton, and of Banbury, and Banbury Castle; in the partial

destruction of Lord Spencer’s house[B] at Wormleighton, and in sending a

summons to Warwick Castle[P] to surrender.

he reign of King Charles I. showed a widening of the difference between

the ecclesiastic and puritan elements of the English community—elements

which were the centres of the subsequently enlarged sections, royalist and

parliamentarian. In the later dissentions between the King and the Commons

it was [Pg 7]early apparent how widespread had been the alienation of the

people from the King’s cause—an alienation heightened, as Green in his

“Short History” tells us, by a fear that the spirit of Roman Catholicism,

so victorious on the continent, should once more become dominant in

England. How great was the tension may be known from the fact of the

contemplated emigration to the American colonies of such leaders as Lord

Saye and Sele, Lord Warwick, Lord Brooke, and Sir John Hampden and Oliver

Cromwell. When the rupture at last came, the Parliament was found to have

secured the larger arsenals, and also to have forces at its disposal in

the trained bands of London and in the militia, which it was enabled

rapidly to enrol. Though the unfurling of the Royal Standard near

Nottingham failed to secure many adherents to the King’s cause, Essex

hesitated to attack the royalists when they might have been easily

dispersed, thinking no doubt to overawe the King by mere show of force.

Yet when Charles began recruiting in the neighbourhood of Shrewsbury, he

was soon able to gather an army, and on October 12th, 1642, he commenced

his march upon London. The astute and carefully moderate policy of the

Commons was to rescue the King from his surroundings, and to destroy[Pg 8] the

enemies, especially the foreign enemies, of the State, about the King’s

person. The sanctity of the King’s person was yet a prominent factor—the

belief in divinity of Kingship, notwithstanding all the misrule there had

been, was yet alive in the hearts of the people. Therefore when the King

had gathered his forces together and began his Southward march, Lord Essex

with his army was commissioned “to march against his Majesties Army and

fight with them, and to rescue the persons of the King, Prince and Duke of

York.” The Earl of Essex, with the Parliamentarian forces, was at that

time in Worcestershire, endeavouring to prevent the recruiting of the

King’s troops; and though the Earl moved two days later on by rapid

marches into Warwickshire, it was only to find that he had been

out-marched by the King, who, after resting at Southam, stood with the

Royalist army at Edgcot across the way to the capital. That this had been

accomplished, notwithstanding the opposition of the strongholds of Warwick

and Coventry, speaks not unfavourably for the generalship of Earl Lindsay,

the King’s Lieutenant-General, whom we find at Edgcot contemplating an

attack upon Banbury Castle. The King’s was a good position: it commanded

all the roads to London, held Banbury in its hand, [Pg 9]covered the Cherwell

bridge and fords, and had within touch the dominating escarpment of Edge

Hill. If the purpose was the subjection of some prominent leaders of the

Parliamentarians it succeeded only in the taking of Lord Saye and Sele’s

house at Broughton, and of Banbury, and Banbury Castle; in the partial

destruction of Lord Spencer’s house[B] at Wormleighton, and in sending a

summons to Warwick Castle[P] to surrender.

Kineton, on October 22nd, was the headquarters of the Parliamentary army, the troops in the evening disposing themselves on the surrounding plain. “The common soldiers have not come into a bed, but lain in the open field in the wet and cold nights,” says the Worthy Divine[PG] “and most of them scarcely eat or drank at all for 24 hours together, nay, for 48, except fresh water when they could get it.” The want of transport, which had necessitated Hampden and Hollis struggling behind a day’s march in the rear in the neighbourhood of Stratford-on-Avon, had no doubt entailed these privations upon the army. Nor do the Royalists appear to have fared better, for Clarendon[B381] complains of the hostility of the country people, stating also that the circuit in which the battle was fought, being between the dominions of Lord Saye and Lord Brooke, was the most[Pg 10] eminently corrupt of any in the kingdom. The King’s forces seem to have been quartered about the country between Wormleighton and Cropredy, Prince Rupert with his cavalry near Wormleighton, the King himself staying at Edgcot House, whilst the main body of the army occupied the slopes and high lands on the Northamptonshire side of the Cherwell vale near by. Thus the three roads North of Banbury were dominated by the Royalist troops, and the fourth, the old London road, was within striking distance.

The preaching of the local divines, Robert Harris, John Dod, and Robert Cleaver, had no doubt added largely to the enthusiasm of the country folk for the cause of the Commons. Though no great increase of the King’s forces could be expected in such a district, yet there is an interesting account in Kimber and Johnson’s Baronetage[NO] (1771) of a country gentleman Mr. (afterwards Sir Richard) Shuckburgh:

“Sir Richard Shuckburgh, Knt., eldest son and heir, was in no way inferior to his ancestors. As King Charles I. marched to Edgecot, near Banbury, on October 22nd, 1642, he saw him hunting in the fields with a very good pack of hounds, upon which it is reported that he fetched a deep sigh, and asked who the gentleman[Pg 11] was that hunted so merrily that morning when he was going to fight for his crown and dignity; and being told that it was this Richard Shuckburgh, he was graciously ordered to be called to him, and was by him very graciously received. Upon which he went immediately home, armed all his tenants, and the next day attended him in the field, where he was knighted, and was present at the battle of Edge Hill. After the taking of Banbury Castle, and his Majesty’s retreat from those parts, he went to his own seat and fortified himself on the top of Shuckborough Hill, where, being attacked by some of the Parliament forces, he defended himself till he fell, with most of his tenants about him; but being taken up and life perceived in him, he was carried away prisoner to Kenilworth Castle, where he lay a considerable time, and was forced to purchase his liberty at a dear rate.”

A fight for the possession of Lord Spencer’s house at Wormleighton was the Saturday evening’s prelude to the Sunday’s battle. It had been garrisoned by some Parliamentarian troops sent by Essex, and in Rupert’s attack some prisoners were taken, from whom, it is said, the whereabouts of the Parliamentarian army was learned.[Y] The house is said to have been partly[Pg 12] burned down in the fight, but it is not clear whether it happened then or in the year 1643. Though with the Parliamentarians in the early part of the Rebellion, Lord Spencer became Royalist long ere the campaigns were over. The fact of an outpost being pushed so far as Wormleighton shows that the Dassett Hills were held by the Parliament forces. The Royalists had marched into the heart of a hostile country, Warwick Castle and Lord Brooke on the N.W., Fawsley House and the Knightleys on the N.E., and on the South, Sir A. Cope and Hanwell Castle, and Banbury and Broughton Castle. Lord Northampton’s lands on the Western border of Oxfordshire were near enough to find touch with the King. His house played locally a most prominent part for the Royalist cause, and its military leadership was of the best.

arly on the morning of Sunday, October 23rd, Prince Rupert forwarded

information to the King that the camp fires of the Parliamentarian army

had been seen on the plain between Edge Hill and Kineton. With keen

foresight Earl Lindsay abandoned the intended advance upon Banbury, and

speedily[Pg 13] began the movement of the Royalist army towards the fringe of

hills which dominates the Warwickshire vale. It seems at first strange

that the Parliamentarians, familiar as so many of them were with the

physical features of the neighbourhood, should have neglected when so near

to secure possession of some part of the Edge Hill ridge. This, however,

is explained in a pamphlet of the time,[PH] “An Exact and True Relation of

the Dangerous and Bloudy Fight between his Majestie’s Army and the

Parliament near Keynton.” Therein we learn that the artillery were

unready, for want of draught horses, and with Colonel Hampden and Colonel

Grantham were forced to be left behind, and hence no advance could safely

be made beyond Keynton.

arly on the morning of Sunday, October 23rd, Prince Rupert forwarded

information to the King that the camp fires of the Parliamentarian army

had been seen on the plain between Edge Hill and Kineton. With keen

foresight Earl Lindsay abandoned the intended advance upon Banbury, and

speedily[Pg 13] began the movement of the Royalist army towards the fringe of

hills which dominates the Warwickshire vale. It seems at first strange

that the Parliamentarians, familiar as so many of them were with the

physical features of the neighbourhood, should have neglected when so near

to secure possession of some part of the Edge Hill ridge. This, however,

is explained in a pamphlet of the time,[PH] “An Exact and True Relation of

the Dangerous and Bloudy Fight between his Majestie’s Army and the

Parliament near Keynton.” Therein we learn that the artillery were

unready, for want of draught horses, and with Colonel Hampden and Colonel

Grantham were forced to be left behind, and hence no advance could safely

be made beyond Keynton.

Hampden had with him three regiments of foot, nine or ten troops of horse, some companies of dragooners, and seven pieces of cannon, with the necessary ammunition train,[PB] perhaps about 4,000 men in all. The troops of the Parliament were quartered in the villages of the plain. Tradition says that Tysoe was occupied, and that the soldiers took the bread from the village ovens ere they marched down street to the fight. But of the doings at Compton in the Hole, barely a mile distant, during the occupation we[Pg 14] know nothing.

It is hard also to understand that there should have been anything in the nature of a surprise[B] in the Royalist advance, for within a district so sympathetic to their cause, one would have supposed the Puritan leaders to have been immediately informed of every movement of their enemies. Indeed, in another quaint pamphlet, “A Letter sent from a Worthy Divine,”[PG] the writer says that the alarm came at about eight o’clock in the morning, that the enemy were advancing, and that “it pleased God to make myself the first instrument of giving a certain discovery of it, by the help of a perspective glass, from the top a hill.”

Deploying, therefore, before daybreak, across Cropredy Bridge, then narrower than at present, and no doubt crossing the Cherwell at certain fords also, the King’s forces marched by way of Mollington to Warmington, where they had been preceded by Prince Rupert’s horse, who would have travelled across the Southern part of the Dassett Hills. It is said[B] that “the foot were quartered at so great distance that many regiments marched seven or eight miles to the rendezvous, so that it was past one of the clock before the King’s forces marched down hill.” Much delay would be occasioned in getting the [Pg 15]troops across the river Cherwell, not so easy to be forded at that time of the year. The narrow bridge[1] would allow but slow passage for 10,000 or 12,000 men, with all the impedimenta of war material. Another pamphleteer[PA] says “the King’s horse were at the rendezvous between ten and eleven; the van of the foot an hour later, and the rear and artillery, including the Lord Lt. General’s own regiment, not until two hours after.”

As the Parliamentarian troops take up their position upon the plain, it is worth while to pause for a few minutes to look at the composition and armament of the two forces. Many of the troops on both sides appear to have been indifferently provided with weapons. Implements of warfare that had not been in use since the Wars of the Roses—the long bow, the cross bow, &c.—resumed their places amongst the accoutrements of the men at arms.[a] There were the heavy horse in iron casques, breast-plates and greaves, the musketeers with their matchlocks, and the dragoons or dragooners,[J118] with sword and matchlock. These last seem to have been so called from the drake, the firearm they once carried, and though not strictly speaking cavalry, [Pg 16]yet accompanying and supporting them. Each regiment of Lord Essex’s army carried a standard inscribed on the one side with the watchword of the Parliament, “God with us,” and on the other side the motto of the regimental commander; Lord Saye and Sele’s were the blue coats, the Commander’s were orange and Lord Broke’s purple; Colonel Ballard’s troops were clad in grey, Colonel Holles’ in red, and Lord Mandeville’s in blue. Across his breastplate each officer of the Parliamentary army wore an orange scarf, the commander’s colour.

There were on the side of the Parliament eleven regiments of foot, forty-two troops of horse, and 700 dragoons, numbering according to Nugent about 13,000, though the officers in their account[PH] place their strength as low as 10,000, which may have meant prior to the arrival of Hampden with the artillery and rear troops. The Royalist army is stated to have possessed 1,000 horse and 4,000 foot more;[G256] in all 14,000 foot and 4,000 horse and dragoons—but as very few troops were of full compliment the numbers were no doubt over estimated. The full strength of a foot regiment was 1,200, of a troop of horse about 120[x26] and of dragooners about the same number to each company.

The Red and the Blue Regiments of the King’s[Pg 17] foot were so named from the colour of their uniforms, the former being the King’s foot guards. In cavalry, however, it was that the Royalist army was predominant—more so, perhaps, from the quality of the material than from any superiority of equipment, Prince Rupert’s show troop being a prominent example. Cromwell, in a speech before Parliament,[q] bore testimony on this point, explaining his reconstruction of the army as having arisen from the fact that “such base and mean fellowes,” tapsters and serving men as they then had, not being “able to encounter gentlemen that had honour and courage and resolution in them, He strove to find such as had the spirit of God in them.”

Towards mid-day the royalist army had occupied the whole length of the brow of the hill between the Sun Rising and Arlescot; the left wing at the Sun Rising, the centre at about the point where the Round House now stands[2] and the right wing at Knowle End, where the road to Kineton descends the hill. Well had it been for the King had the advice of so able a soldier as Earl Lindsay prevailed at the council of war over the more impetuous policy of Rupert. He [Pg 18]had the strong position of the hill crest, with convenient roads for the rapid movement of troops, and, moreover, natural advantages which would have masked those movements. Essex would have hesitated to risk the assault of a position of such strength, especially when defended by a force greater than his own. These advantages were, however, abandoned for the more dashing policy of Rupert to descend to the plain and at once give battle. It must not be forgotten, however, that the knowledge of the enemy’s artillery with part of the army being far in the rear,[PB] but approaching with what speed they could, and the difficulty of provisioning the army in a hostile district,[B] would give weight to Rupert’s counsel. Brilliant cavalry officer as he undoubtedly was, his defiance of control caused the Earl to resign his command, and the disposition of the forces to devolve upon Earl Ruthven, and so he decided against the King the fortunes of the then commencing war.

The Parliamentarians had in the meantime not been idle. Turning aside from church, whither they had been going, the divines encouraged the soldiers as they stood drawn up ready for the fight. Poor retrenchment as they were said to have had, the ground lent itself to preparation for defence: the thick growth of[Pg 19] furze tied and wattled together on the gently sloping upland: (the old phrase a “good bush whacking” may point to its service in fight). Also there was the long ditch with its wet clay banks covering the front. It is certain that a large number of the force were fighting on their own ground and for their own homes. Evidence shows how heavy the fight was thereabouts.

The centre consisted of three regiments of infantry, including one of the general’s, under Lord Brooke and Colonel Ballard, another regiment, under Colonel Holles, being in the rear. These faced the Battledon Farm, about one mile North-West of Radway, and on some rising ground to the right the artillery was posted.

The right wing moved towards the Sun Rising. It was composed of four brigades of horse, under Sir John Meldrum, Col. Stapleton, and Sir William Balfore (the divisional general), with Col. Fielding’s brigade and some guns in the rear. Capt. Fiennes’ regiment was with this wing, which was covered on the right by some musketeers. Captain Oliver Cromwell fought there also. Infantry, including the Oxfordshire Militia under Sir William Constable and Lord Roberts, took up the intervening space between the centre and the right wing. The cavalry of the left wing, covering the Kineton road, was[Pg 20] made up of twenty-four troops, under Sir James Ramsay: the infantry in five regiments, officered by Cols. Essex and Chomley and Lords Wharton and Mandeville, with Sir Wm. Fairfax in reserve, occupied the ground between the cavalry and the main body. A few guns were placed in the rear of the horse.

Imposing indeed must the sight have been in bright sunlight of that early Sunday afternoon as the Royalist troops, began to descend the hill side! The slopes do not appear to have been so thickly wooded as they are now, and the unenclosed country, without the many obstacles of fence and hedgerow,[B388] offered all that a cavalry officer could desire for the exercise of his art and arm. Before this[PF] the King had summoned the officers to the royal tent, and in his brief speech had said: “My Lords and Gentlemen here present,—If this day shine prosperously for us, we shall be happy in a glorious victory. Your King is both your cause, your quarrel, and your captain. The foe is in sight. Now show yourselves no malignant parties, but with your swords declare what courage and fidelity is within you. * * * Come life or death, your King will bear you company, and ever keep this field, this place, and this day’s service in his grateful remembrance.” [Pg 21]The King,[a286] wearing a black velvet mantle over his armour, and steel cap covered with velvet on his head, rode along the lines of his troops and spoke to them: “Matters are now to be declared with swords, not by words.”[PF] Perhaps, however, the most beautiful of these records is that of the truly soldier-like prayer of Lord Lindsay,[a286] “O Lord, Thou knowest how busy I must be this day; if I forget Thee do not Thou forget me.”

I

BATTLE OF EDGE HILL

(Commencement of Battle.)

The King’s centre, under General Ruthven, moved forward as far as the village of Radway. The six columns of infantry of which it was composed were under the divisional command of Sir Edmund Verney and Sir Jacob Astley; Earl Lindsay and Lord Willoughby led their Lincolnshire regiment. Between these and the right wing were eight other regiments of infantry. The cavalry of the right wing, under Prince Rupert, commenced slowly the steep descent of the road through Arlescot wood and the Kineton road, the base of which is known as the Bullet Hill, and drew up there in a meadow at the bottom of the hill.[PB] Fiennes states that the better opportunity for the Parliamentarian attack would have been before the artillery and rear came down the hill, which they were a long time in doing. The left wing rested upon the Sun[Pg 22] Rising, Col. Ennis and Col. Lisle’s dragoons covering the flank; near by were the Welsh soldiers and Carnarvon’s regiments of pikemen. In advance Wilmot’s two regiments of horse were working across the Vale of the Red Horse, Digby’s reserve covering the crest of the hill.

Lord Essex’s artillery were the first to break the peace of the day, a challenge immediately replied to by the Royalist guns near Radway. Wilmot, of Adderbury, made the first aggressive movement in a charge upon the Parliamentarian right, and though some success seems to have attended it, yet it can scarcely have been of so much importance as Clarendon the Royalist historian[B] makes out, for he writes: “The left wing, commanded by Wilmot, had a great success, though they had to charge in worse ground, amongst hedges and through gaps and ditches which were lined with musketeers. Sir A. Aston, with great courage and dexterity, beat off these musketeers with his dragoons; and then the right wing of their horse ‘was easily dispersed, and fled the chase fearlessly.’ The reserve, seeing none of the enemy’s horse left, thought there was nothing more to be done but to pursue those that fled, and could not be contained by their commanders, but with spurs and loose reins followed the chase which the[Pg 23] left wing had led them. Thus while victory was unquestionable, the King was left in danger from the reserve of the Parliament, which, pretending to be friends, broke in upon the foot, and did great execution.” Certainly in charge and counter charge at this stage of the attack, the Parliamentarians show to no advantage, and the dispersal of the dragoons, musketeers, and part of Fielding’s horse, seems to have taken place, but the subsequent successful charge of Balfour’s and Stapleton’s brigades makes it clear that they were not involved in any disaster.

On the right wing, soon after the time of Wilmot’s charge near the Sun Rising, Rupert’s troops moved down the foot of the hill in the direction of the Kineton road and towards Ramsay’s horse, which advanced to meet them. The Parliamentary general had lined the hedgerows on his flank with musketeers, and had placed ranks of musketeers between his horse. But as the cavaliers[3] swept down the slope a defect was visible in the Parliamentarian ranks, and Sir Faithful Fortescue’s Irish troop threw off their orange scarves and deserted bodily, not quite soon enough, it seems, to save themselves, for a score or so of saddles were emptied in the [Pg 24]onrush of Rupert’s cavaliers. The roundhead ranks were disordered, for the troops had fired their long pieces wildly, and scarcely waiting the meeting, they fled, leaving the musketeers to be cut up. The troops of cavaliers swept through them scattering and destroying all in their way; then deflecting a little to the left they pressed back the mass of fugitives upon the foot regiments of Essex, Mandeville and Chomley which in turn were overthrown, and the artillery captured. Even Wharton’s regiment and Fairfax’s reserve were hurled back. Ramsay, the cavalry general, was carried for two miles in the melee, and with some of his troopers found a way through the hostile lines to Banbury.[a] Rupert continued in unsparing pursuit even into the streets of Kineton and as far as Chadshunt. Thus was the left wing of Lord Essex’s army dispersed, though to reform for a later phase of the fight. After so much success the baggage proved to be too attractive to the victors, and had the time wasted in plundering been spent in an attack upon the rear of the Parliamentarian army, then the reign of Charles Stuart might have had a less tragic ending. But with all this, it must be borne in mind that the incident of the rolling up of a wing was repeated in other battles of the war which were more[Pg 25] disastrous to the King’s cause. Sir James Ramsay at a Court Martial at St. Albans[Vn] in November of the same year made a vindication of his conduct.

An amusing letter from Captain Kightley tells of this phase of the fight. He admits that in part his own regiment ran away, and it seems to be probable that Captain John Fiennes was in no better way, though in the subsequent rally and attack upon Prince Rupert both did very good service.

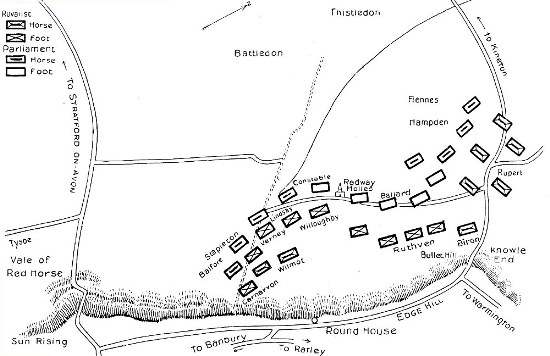

The right wing of the Puritan forces had in the meantime become aggressive. It was the beginning of the great turning movement which was repeated in each of the great battles of the war by the Parliamentarians, in fact, so evident at Naseby and Marston Moor, as to compel belief in studied uniformity of plan. The abandonment or weakening of one wing, then the use of all the weight of the other wing with the foot as a centre pivot, to out-flank, attack, and crush in succession the opposing wing and centre of the Royalist army. Balfore, Meldrum, and Stapleton’s brigades charged Wilmot’s cavalry with such vigour that these were thrust back upon the three regiments of pikemen, under Lord Carnarvon, and chased up the hill side. Cannon balls and other remains of the[Pg 26] fight found on the hill slopes at Lower Westcote near the Sun Rising are evidence of this attack. The infantry under Roberts and Constable having moved forward to aid in the attack upon Carnarvon, now wheeled upon the King’s centre, which soon became the focus of a fierce and bloody fight, for the elated Roundhead horse, after crushing in the Royalist left wing, hurled themselves also upon the flanks of the nearest troops of the King’s centre, and the blue-coated Broughton horsemen had a busy time of it amongst the royalist gunners as they rode through the battery. Earl Lindsay’s Lincolnshire regiment, which he had led pike in hand, received the brunt of the attack; it was overpowered, and the unfortunate general left for dead with a musket ball in his thigh. The Red Regiment moved up in support, only in turn to be cut up and almost annihilated, and Lord Willoughby was made prisoner also in the attempt to rescue his father the Earl. Then followed a brilliant personal fight for the royal standard, but the Puritan horseman Copley cut down Sir Edmund Verney, knight marshal of the King’s horse, and standard bearer, and secured the prize. The success of this attack was largely brought about by the ruse alluded to, where, “pretending to be friends,” they broke[Pg 27] in upon the King’s regiments. If it is true that they got so near as to shake hands, the business must have been very simple. Verney had presentiment of his death, and the severed hand clasping the standard shaft is said to be yet sadly searched for by the ghost of Claydon House.[Vr] On the finger of the hand was a ring, a king’s gift. Nugent says about the standard’s recapture: “The Royal standard was taken by Mr. Young, one of Sir William Constable’s ensigns, and delivered by Lord Essex to his own Secretary, Chambers, who rode by his side. Elated by the prize, the Secretary rode about, more proudly than wisely, waving it round his head. Whereupon in the confusion, one of the King’s officers, Captain Smith, of the Lord John Stewart’s troop, seeing the standard captured, threw round him the orange scarf of a fallen Parliamentarian, and riding in among the lines of his enemies, told the Secretary that ‘it were a shame that so honourable a trophy of war should be borne by a penman.’ To which suggestions the credulous guardian of this honourable trophy consenting, surrendered it to the disguised cavalier, who galloped back with it amain, and before evening received knighthood[4] under its shadow.”

[Pg 28]Brooke’s, Hollis’, and Ballard’s infantry, moved across part of the ground abandoned by Ramsay’s horse to attack the right flank of the King’s centre, an attack which soon becomes as disastrous to the Royalists as that on the other flank where Lindsay has fallen. In fact, the regiments of foot from the Parliamentary rear with Constable’s infantry and Stapleton’s horse, made a combined assault upon the King’s centre, which they commenced breaking up. In vain were the royalist reserves hurried forward. The Blue Regiment was cut off by Sir Arthur Haselrigge. Stapleton made a dash, and the King, who had been watching the fickle fortunes of his soldiers from a mound (now the King’s Clump) near Radway, narrowly escaped being made a prisoner. The timely interference of a body of royalist horse—an interference not of sufficient weight to stop the tide of the Puritan attack, but only to stay it for a few moments—enabled the King to gain the shelter of the hill, whither also the fragments of some of his regiments are compelled to follow.

II

BATTLE OF EDGE HILL

Advance of Hampden_Retreat of Rupert & King

Meanwhile Rupert had been lost to sight in [Pg 29]Kineton streets. When he learned that the fortunes of the day were, in other parts of the field, in full flow against his cause, he and his cavaliers re-formed for the retreat. The place is still known as Prince Rupert’s Headland. There was, however, another factor to be taken into consideration. Some of Hampden’s green-coated soldiers, stimulated no doubt by the sounds of the fight, had in the meantime come up from Stratford-on-Avon, and were prepared to dispute Rupert’s return. They also succeeded in re-forming many of the fugitives, in which duty Captains Cromwell,[5] Nathaniel Fiennes and Kightley, took part.[q] The guns and infantry opened fire upon the retreating cavaliers, who had a hard fight to regain the hill butt, for Stapleton’s horse, after fighting along the whole of the Royalist line, chased them home. Nevertheless, two of the royal regiments refused to be beaten; falling back upon their guns, they made a stand, probably along the line from Radway to Bullet Hill, and there, reinforced by Rupert’s returning troops, they held their ground, repulsing the Parliamentarian attacks, and so says Fiennes,[PB] “horse and foot stood together against horse and foot [Pg 30]until night, when the Royalists retired up hill.” It is probably from this stage of the fight that Bullet Hill got its name. The braided lovelock of many a cavalier who rode so exultingly down the hill in the afternoon sunlight had a stain of a far deeper colour ’ere sunset, and with the phase of the fight following the straggling return of Rupert’s Horse, the events of the day seem to have ended. The King would have tried a final charge with some unbroken regiments to test once more the fortunes of the day, but was with difficulty persuaded from so perilous an enterprise.

Each side claims that only the night prevented a completely victorious issue for its cause, but when we consider that the right wing and centre of the King’s army were disorganised, and in part driven up the hill, and that the Parliamentarians were in possession of the battle ground, the Royalists retaining possession only of the low ground from Radway to Bullet Hill, it seems that the advantage rested on the Puritan side. One[a] remained master of the field of battle, the other kept the London road.

Amongst the several estimates of the slain, it is hard to say which is nearest the truth. Clarendon gives the number as 5,000, two parts of whom were Parliamentarian, and one part the[Pg 31] King’s, but the probability is that it was nearer, a half of that number. Fiennes[PB] puts down the losses acknowledged by the Royalists themselves as 2,000. Certainly the records show that they were exceptionally heavy in officers, one writer adducing as a reason that “the rebel officers had fleeter horses, so not so many of them were slain.” During the cold frosty night after the battle the wounded must of necessity have been left exposed, inasmuch as the fight stretched over many miles of country, and was continued until night; nor do the Royalists appear to have been debarred from searching for their wounded, as we learn by the succour of old Sir Gervase Scroop by his son. The King’s troops says Clarenden “had not the shelter of tree or hedge, and after a very cold night spent on the field, without any refreshment of victual or provision for the soldiers (for the country was so disaffected that it not only sent no provisions, but many soldiers who straggled into the villages for relief were knocked on the head by the common people), the King found his troops very thin.” The Parliamentarians, whose baggage had been cut up by Rupert, could not have been in much better plight; some of them, however, fired the Dassett Beacon, and the news of the conflict was thus flashed across country to[Pg 32] London. Though so much is recorded of Mr. Wilmot’s (afterwards Lord Rochester, of Adderbury,) position and work during the day, nothing other than the mere statement is made of a far greater leader, Spencer Compton, Earl of Northampton, than that he was at Edge Hill, with some of the best disciplined men.[MW] It would seem that the extended movement of the Royalist forces along the hill ridge in the early part of the day was to give support to Compton Wynyate, or get aid therefrom. It was but three miles distant. Whether any deflection of Hampden’s force moving from Stratford-on-Avon was made to mask or retard Compton’s men is mere surmise: the main part of Hampden’s rear did not reach the field until the Sunday midnight, when Essex got reinforced by a regiment of horse and two of foot.

The story of successive campaigns, as in this the first fight, resolves itself into the superiority of the heavy armament of the Parliamentarian horse. The improved status of the men added greater force at a later date. With all the dash, and all the value of the light horse of the King for foray, when in the field the cavalier went down before the iron armed horse of the Parliament’s army.

On the following day, the two armies again[Pg 33] drew up, the Parliamentarians having in the early morning retired from the hill side towards Kineton,[PB] but neither showed any disposition to renew the fight. Essex was pressed to do so by some of his more impetuous officers, but wanted the daring necessary for so bold a movement. Charles sent a messenger into the rebel lines with a pardon for Earl Essex, which “messenger returned with so great a sense of danger as not to have observed the number and disposition of the Parliamentary forces.” Later on, Essex retired to Warwick with his troops, and Prince Rupert is reported to have followed, but failed to overtake them, though it is stated that he destroyed many wagons and carriages with munitions, &c. The reconnaissance appears to have been otherwise fruitless, for the King at once marched southward, and received the surrender of Banbury Castle, and also subsequently of Broughton Castle. Lord Saye, Sir Wm. Cobb, of Adderbury, and John Doyley, Esq., were not only proclaimed traitors, but were specially exempted from the King’s pardon.[y430]

The position of the graves in which the slain were buried is about 200 yards south of Thistle Farm, the ground bearing still the name of the Grave Field, and a wych elm marks the site of[Pg 34] one of the graves.

The part that Oliver Cromwell played in the struggle has not unnaturally been the cause of much comment. Carlyle[q101] characteristically cuts the Gordian knot with the statement, “Captain Cromwell was present, and did his duty, let angry Denzil say what he will.”[6] Denzil Hollis’s[o226] charge that Cromwell purposely absented himself from the field may be fairly set aside on the ground of malice, his enmity being openly shown, and moreover it meets contradiction in Cromwell’s own statement:[Q249] “At my first going out into this engagement, I saw our men were beaten at every hand. I did indeed.” Neither can Dugdale’s[C] account of Cromwell’s hurried descent from a church steeple by means of the bell rope, when he saw the Parliamentarian disaster, be received in the face of the letter written by Captain Nathaniel Fiennes,[PB] which ends thus: “These persons underwritten were all of the Right wing and never stirred from their Troops, but they and their Troops fought till the last minute. The Lord Generall’s Regiment—Sir Philip Stapleton, Captain Draper, Serjeant [Pg 35]Major Gunter, Lord Brookes, Captain Sheffield, Captain Temple, Captain Cromwell; Sir William Belfore’s Regiment—Sir William Belfore, Serjeant Major Hurrey, Lord Grey, Captain Nathaniell Fiennes, Sir Arthur Hasilrigge, Captain Longe.” It is equally curious that Captain Oliver Cromwell, of Troop Sixty-Seven,[q100] was at Edge Hill in the place he invariably occupied during the civil war, viz., with the victorious wing, and that the history of the fluctuations of the fight should be repeated in so many of the great battles, Naseby and Marston Moor to wit.

A most true and Exact

RELATION

OF

BOTH THE BATTELS FOUGHT BY

HIS EXCELLENCY

and his Forces against the bloudy Cavelliers.

The one on the 23 of October last near Keynton

below Edge-Hill in Warwickshire,

the other at Worcester by

Colonell Brown, Captain Nathaniel, and

John Fiennes, and

Colonell Sands and some others.

Wherein the particulars of each Battel is punctually set down at large for the full satisfaction of all people, with the Names of the Commanders and Regiments that valiently stood it out.

Also the number and Names of the Chief Commanders that were slain on both sides: All which is here faithfully set down without favour or partiality to either Army.

Written by a worthy Captain Master Nathaniel Fiennes, And commanded to be Printed.

London, Printed for Joseph Hunscott

Novem. 9. 1642.

Mr. Nathaniel Fiennes his Letter to his Father.

My Lord,

I have sent to your Lordship a Relation of the last Battell fought in Keynton Field, which I shewed to the Generall and Lievtenant Generall of the Horse, and divers Colonels and Officers, and they conceive it to be right and according to the truth: For the ill writing of it, I desire that your Lordship would excuse me, for I had not time to write it over again; yet I suppose it may be read, and your Lordship may cause it to be written faire, if your Lordship thinke it worth so much. For that which your Lordship writeth concerning my brother John, is a most false and malicious slander which that fellow hath raised upon him, that he should be the first man that fled on the left wing, when as none of your Lordship’s sonnes were in the left wing, and my brother John was not at all in the field while the fight was; for by occasion that I intreated him on Saturday morning, when we marched towards Keynton (little dreaming of a Battell the next day) to go to Evesham (which was but three miles from the quarter where our Troops lay, before they marched with the Army to Keynton) for to take some Arms that were come thither the night before, for such of our [Pg 39]men as wanted Arms, and so to come after to the Rendevous at Keynton. He could not come thither on Saturday with those men of both Troops which went backe with him to Evesham for their Arms, but the next day he came thither between three or foure of the clock; at which time our left wing being defeated, many of the Runaways met with him as he was coming to the Army; and happily among the rest, this fellow that raised this report; for that Vivers which your Lordship mentioneth, was not Captain Vivers (for he was in Banbury) but a brother of his that was in one of Colonell Goodwin’s Troops, and as I heard my brother say, he saw him there; and I heard my Lord Generall say, that Vivers was one of the first that ran away: Now it seemes that those men that ran away so timely, seeing my brother before them, reported as if he had fled from the Army, which is so contrary to the truth, that he tooke a great deale of pains to make his own men and Captain Vivers’ men which were with him to stand, and to stop the Runaways that came from the Army, and this he did, and made two or three stands, and at length gathered a pretty body upon a hill together, and with them (there being Captain Keightlye’s, and Captain Cromwell’s Troope, at length came to them also) he[Pg 40] marched towards the Town; and hearing the enemy was there (as indeed they were with the greatest part of their horse they made a stand, and sending forth their Scouts to give them intelligence where the enemy and where our Forces were, at length they came to knowledge of Colonell Hampden’s Brigado that was coming another way to the Town, and so joyning themselves unto them, they came to the Army together. My Lord Generall is very sensible of the wrong that this fellow hath done my brother, and will inquire after him to have him punished, as he hath written to my Lord Wharton concerning him, to let you know so much. Master Bond whom he citeth for one of his authors, denies that ere he spake to my brother at all, or that he saw any such thing of flying, as that base fellow reporteth, and this your Lordship shall have under his hand. It had been a strange thing if my brother that shewed so much courage at Worcester, should have been so faint-hearted on this occasion; But I strange that men will give credit to every idle fellow; if they will, they may heare that my Lord Generall and all the Officers, every one of them ran away. But my Lord, as your Lordship hath great cause to be thankfull, together with us, to God, that in all these late actions of danger, hath preserved [Pg 41]the persons and lives of all your three Sons, so also for preserving their honors, and the honor of Religion; that in this cause they have never flinsht, but have all of them in their severall places and conditions been as forward to hazard their persons into the midst of their’s and God’s enemies as any whosever. And of the truth of this (though we do not vapour so much as some do) there are enough, and those very honorable witnesses that can and will affirm it as well as

Your Lordship’s most obedient Son,

NATHANIEL FIENNES.

A most true Relation of the Battell fought by his Excellency and his Forces against the bloudy Cavalliers.

The two and twentieth of October, being Saturday, his Excellency the Earl of Essex came with twelve regiments of Foot, and two and forty Troops of Horse, and a part of the Ammunition and Artillery, to Keynton, a little Market Toun, almost in the mid-way between Stratford upon the Avon, and Banbury, there being three Regiments of Foot, and nine or ten Troops of Horse, with seven Pieces of Cannon, and good store of Ammunition coming after, together with six Companies of Dragooners; the Dragooners, and two of the Regiments of Foot, with the Cannon, and nine or ten Troops of Horse, came to Keynton on Sunday night, a little before the day went down; The Regiment, with the Lord Rochfords, came not into the Army till Monday in the afternoon. The King’s Army was lodged on Saturday night, about Croprede and Edgecot, some 6 or 7 miles from Keynton; and having, no doubt, got intelligence that part of our Army, and Artillery, with a great part of our Ammunition was behinde us, they thought they could not have a better opportunity to fight with our Army, especially if they could get the[Pg 43] advantage of the hill before us, it being a very high and steep assent, which if they were put to the worst might serve them for a Retreat, as it did, it being that which saved them, their Carriages, and the Colours of their Regiments of Foot that ran away; for of those that fought it out, we tooke most of them, excepting onely those two Regiments that stood it out till night, and went off with their horse in an orderly way. The enemy having resolved to give us Battell, and no whit doubting of the Victory, they being more then we were, both in horse and foot (a considerable Brigado of our Army being behinde) and having a great opinion of the resolution of their Souldiers, wherein they were partly deceived, and partly not, as it hapned also on our side; They returned back towards Edge Hill, and made all possible speed to gain the hill before us (which they did, by reason that his Excellency had not timely intelligence of their designe, otherwise we were much neerer the hill, and might have been possessed of it before them). And by that time our Army was drawn out of the Town about a mile and half towards the hill, the Dragooners, and some of the enemie’s Foot were coming down the hill; Their horse having gotten down most of them on their right hand, and placed themselves in[Pg 44] a fair Meadow, at the bottom of the hill; Their Cannon and Ammunition, with the Rere of their foot, were something long ere they came down. And if we had charged them before their Cannon and all their Foot were come down, we might have had a great advantage: but they got all down into the Meadow at the foot of the hill, and there drew up their Army very handsomely, their horse being on their right Wing for the most part, and their Dragooners, and some few Troops of horse on their left Wing; some of their prisoners said they had four Regiments of horse on that wing also; but I could never speak with any of our Army, that either saw any such number of horse, or could tell what they did, unlesse they went directly to Keynton, to plunder the Carriages without charging our Army at all.

For our Army, it was drawn up upon a little rising ground, and being amongst the horse, I could not well discern how the foot were drawn up; only I knew they were most of them a good space behinde the horse, when we began to charge: but for the horse, there were three Regiments on the right Wing of our Army, viz., The Lord Generalls Regiment commanded by Sir Philip Stapleton; Sir William Belfore’s Regiment, Lieutenant Generall of the Horse;[Pg 45] and the Lord Fielding’s Regiment, which stood behinde the other two, in the way of a reserve.

On the right Wing of our Army, was Sir James Ramsey, with some 24 Troops, for many of our Troops were not in the Field that day. The Armies being thus placed one against another with no great oddes of the winde or ground (but what their was of winde the enemies had it, the ground being reasonable indifferent on both sides) after many shot of Cannon which did very little hurt amongst us, and very much amongst them, their foot advancing for the most part against our right Wing, and their horse against the left Wing of our Army. Their horse had the better of our horse that were on our left Wing, and routing them, drove them back upon our foot, and amongst the rest, upon Colonell Hollis his Regiment, which was in the Rere, and they brake through it, yet they ran not away, nor seemed to be at all dismayed at it; but four other Regiments ran away, and fought not at all, and many of them cast away their Colours, and so the enemy took them up, having scarce got so much as one Colour or Cornet of those Regiments or Troops that fought, whereas all the Colours that we got from them, and the King’s Standard, which we had a long time in our possession, were taken out of the midst of[Pg 46] their best Regiments that fought it out very resolutely: Our left Wing being thus put to the worst, the day was very desperate on our side; and had not God clearly fought for us, we had lost it; for had the enemie’s horse when they routed the left Wing, fallen upon the Rere of our right Wing, in all probability the army had been wholly defeated: But they made directly to the Town, and there falling upon our Carriages, most barbarously massacred a number of poor Waggoners and Carters that had no arms to defend themselves, and so fell to pillaging and pursuing those that ran away, so long till they met with Colonell Hampden, who with the other Brigado of the Army (which came with the Artillery and Ammunition which was behinde) was by this time come near to Keynton, and the enemie’s Troops falling upon him as they pursued our men that ran away, he gave them a stop, and discharging five pieces of Cannon against them, he slew some of them; whereupon they returned in some fear and disorder: But when they came back into the Field, they found all their Infantry, excepting two Regiments, cut in pieces or defeated and run away; for it pleased God to put such courage into four or five of our Regiments of foot, and two Regiments of horse, the Lord Generall’s commanded by Sir Philip[Pg 47] Stapleton, and Sir William Belfore, that they defeated all their Regiments of foot, except two. Sir William Belfore’s Regiment of horse charged a Regiment of the enemie’s foot, before any foot came up to assist him, and breaking into it cut most of it off; and after, by the assistance of some of our foot, he defeated another Regiment, and so we got up to the greatest part of the enemies Ordnance, and took them, cutting off the Geers of the horses that drew them, and killing the Gunners under the Carriages, but were forced to leave them without any to guard them, by reason we were fain to make good the day against severall Regiments of foot that still fought with a good deal of resolution; especially that which was of the King’s Guard, where his Standard was, close by which Sir William Belfore’s Regiment rode when they came from taking the Ordnance; and they taking us to be their friends, and we them, some of our Company, shook hands with some of them, which was the cause that after riding up towards the Lord Generall’s Regiment of horse, they gave fire upon Sir William Belfore’s Regiment, and discerning each other to be friends, we joyned Companies; and so with half the Lord Generall’s Regiment, which his Excellency himself led up, charging the King’s Regiment, we defeated it,[Pg 48] took the Standard, took the Generall of the King’s Army, the Earl of Lindley, and his son, and Colonell Vavasor who was Lieutenant Colonell of that Regiment, and killed Sir Edward Varney upon the place (who carryed the Standard), Colonell John Munroe, and divers others: In this charge, and generally throughout the day, the Lord Generall’s Troop, consisting most of Gentlemen, carried themselves most valiantly; and had all our Troops, of our left Wing been made of the same metall, the enemy had not made so easie an impression into them. And what is said of my Lord Generall’s Troop, may most truly, and to his high praise, be said of himself; and also that noble Earl, the Earl of Bedford, Generall of the horse, for both of them rode all day, being in the heads of the severall Troops and Regiments to give their directions, and to bring them on upon the enemy, hazarding their persons as far and further than any particular Souldier in the Army. By this time all the enemie’s foot being dispersed and gone excepting two Regiments, they retiring themselves, found their Ordnance behind them without any Guard, and there they made a stand, and made use of their Cannon, shooting divers shot at us; at which time our Regiment of foot began to want Powder, otherwise we had[Pg 49] charged them both with horse and foot, which in all probability would have utterly ruined their Infantry, for those two Regiments were the onely stake which they had now left in the hedge: But partly through want of Ammunition, and partly being tyred with fighting all the day (the whole brunt of the Battell having been sustained by two Regiments of horse, and four or five of foot) we made no great haste to charge them, so that the enemies horse that had been pillaging at Keynton had leisure to come about, some on one hand of us, and some on the other, and so joyned with their foot: Yet as they came back on our left hand, Sir Philip Stapleton, with his Troop, went out to charge some 4 or 5 Troops of them which went away from him as fast as they could upon the spur to the rest of their Company, and their foot that stood by their Ordnance, most of the enemie’s horse being gathered to their foot, most of our horse also gathered to our foot, and so we stood horse and foot one against the other till it was night. Our Army being thus possessed of the ground that the enemy chose to fight upon, stood there all night; the enemy having withdrawn their Army to the top of the hill for more security to themselves, where they made great fires all the night long, whilst we in the meantime drew backe[Pg 50] some of our owne Ordnance, which they had once in their possession, and some of their’s which they had left behinde.

The next morning, a little before it was light, we drew back our Army towards the Town to our other Brigadoe and Artillary and Ammunition that was come and lodged there, and the enemy drew out their horse in the morning upon the side of the hill, where staying till towards night, whil’st the foot were retyring behinde the hill and marching away, at length a little before night, their horse also marched away; and about an houre after, our horse also marched towards their Quarters, the Foot and some horse staying all night in their Quarters, in and before Keynton; and the next day the whole Army both horse and foot marched towards Warwicke to refresh themselves; instead of which, if they had marched towards Banbury, they would have found more victuals, and had in all probabilities dispersed all the foot of the King’s Army, and taken his Canon and Carriages and sent his horse farther off to plunder, whereas now because we did not follow them though they quitted the field to us which we fought on and left their quarter before us the next day, yet they begin to question who had the day: It is true, there were Colours and Canon taken on both[Pg 51] sides, without any great difference in the numbers, but for the number and quality of men slaine and hurt, it is verily believed, they left foure times as many at the least as we did, and in saying foure times as many, I am confident I speake much below the truth. There were slaine on their side the Earl of Lindsey Generall of their Army, the Lord Aubigney, brother to the Duke of Richmond, Sir Edward Verny Colonell, John Monroe and divers other gentlemen and Commanders, and very many hurt. Of our side were slaine the Lord St. John, Colonell Charles Essex, Lieutenant Colonell Ramsey and none other of note, either killed or dangerously hurt that I can heare of; They acknowledge that they lost 1200 men, but it is thought they lost 2000: and whereas they report we lost divers thousands, where one man judgeth that we lost 400, ten men are of opinion that we lost not 200 Souldiers, besides the poore Waggoners and Carters.

These persons underwritten were all of the Right wing and never stirred from their Troops but they and their Troops fought till the last minute.

| The Lord Generall’s Regiment | Sir William Belfore’s Regiment | |

| [Pg 52]Sir Philip Stapleton | Sir William Belfore | |

| Captain Draper | Sergeant Major Hurrey | |

| Sergeant Major Gunter | Lord Grey | |

| Lord Brookes | Captain Nathaniell Fiennes | |

| Captain Sheffield | Sir Arthur Hasilrigge | |

| Captain Temple | Captain Longe | |

| Captain Cromwell |

A FULL AND TRUE RELATION of the great Battell fought between the King’s Army, and his Excellency, the Earle of Essex, upon the 23 of October last past (being the same day twelve-moneth that the Rebellion broke out in Ireland) sent in a Letter from Captain Edward Kightley, now in the Army, to his friend Mr. Charles Lathum in Lumbard Street, London, Wherein may bee clearly seene what reason the Cavaliers have to give thankes for the Victory which they had over the Parliaments Forces.

Judges 5-31.

“So let all thine enemies perish O Lord, but let them that love him, be as the Sun when he goeth forth in his might.”

London: Printed November the 4, 1642.

[Pg 54]Loving Cousin, I shall make so neare as I can a true, though long relation of the battell fought betweene the King’s Army and our Army, under the conduct and command of my Lord Generall on Saturday October 22. Our Forces were quartered very late and did lie remote one from the other, and my Lord Generall did quarter in a small Village where this Battell was fought, in a field called Great Kings Field, taking the name from a Battell there fought by King John as they say: on Sunday the 23 of October about one of the clocke in the afternoon, the Battell did begin and it continued untill it was very darke, the field was very great and large, and the King’s Forces came down a great and long hill, he had the advantage of the ground and wind, and they did give a very brave charge, and did fight very valiantly: they were 15 Regiments of Foot and 60 Regiments of Horse, our Horse were under 40 Regiments and our Foot 11 Regiments: my Lord Generall did give the first charge, pressing them with 2 pieces of Ordnance which killed many of their men, and then the enemy did shoote one to us, which fell 20 yards short in a plowed Land, and did no harme, our Souldiers did many of them run away to wit blew Coats and Grey Coats, being two Regiments, and there did runne away,[Pg 55] 600 horse, I was quartered five miles from the place, and heard not anything of it, until one of the clocke in the afternoone. I halted thither with Sergent Major Duglis’ troope, and over-tooke one other troope, and when I was entiring into the field, I thinke 200 horse came by me with all the speed they could out from the battell, saying, that the King had the victory, and that every man cried for God and King Charles. I entreated, prayed and persuaded them to stay, and draw up in a body with our Troopes, for we saw them fighting, and the Field was not lost, but no perswasions would serve, and then I turning to our three troopes, two of them were runne away, and of my Troope I had not six and thirtie men left, but they were likewise runne away, I stayed with those men I had, being in a little field, and there was a way through, and divers of the enemy did runne that way both horse and foote, I tooke away about tenne or twelve horse, swords, and armour, I could have killed 40 of the enemy, I let them passe disarming them, and giving the spoile to my Troopers; the Armies were both in a confusion, and I could not fall to them with out apparent loss of my selfe and those which were with me, the powder which the Enemy had was blowne up in the field, the Enemy ran away as well as[Pg 56] our men, God did give the victory to us, there are but three men of note slain of ours, namely my Lord Saint John, Collonell Essex, and one other Captaine, whose name I have forgot: Captaine Fleming is either slaine or taken prisoner, and his Cornet, he had not one Officer which was a souldier, his Waggon and money is lost, and divers of the Captaines money and Waggons are lost, to great value, our foote and Dragooners were the greatest Pillagers, wee had the King’s Standard one houre and a halfe, and after lost it againe: Wee did lose not above three hundred men, the enemy killed the Waggoners, women and little boyes of twelve years of age, we tooke seventeene Colours and five pieces of Ordnance, I believe there were not lesse than three thousand of the enemy slaine, for they lay on their own ground, twenty, and thirty of heapes together, the King did lose Lords, and a very great many of Gentlemen, but the certaine number of the slaine cannot bee knowne, we did take my Lord of Lindsey, Generall of the Foote, being shot in the thigh, who dyed the Tuesday morning following, and his body is sent away to be buryed, the Lo: Willoughby his son was taken, Lunsford, Vavasour, and others, being prisoners in Warwick Castle; on Munday there did runne from the King’s Army 3000, foote[Pg 57] in 40, 50, and 60 in Companies, wee kept the field all Sunday night, and all Munday, and then marched to our quarters, and on Munday the enemy would have given us another charge, but they could not get the foote to fight, notwithstanding they did beate them like dogs, this last Relation of the enemy I received from one which was a prisoner and got away.

Banbury is taken by the King, there was 1000 Foote in it, the Captaines did run away, and the souldiers did deliver the Toune up without discharging one Musket. It was God’s wonderful worke that we had the victory, we expect to march after the King. The day after the Battell all our Forces, horse and foote were marched up, and other forces from remote parts, to the number of 5000, horse and foote more than were at the Battell, now at my writing, my Lord Generall is at Warwick, upon our next marching we doe expect another Battell, we here thinke that the King cannot strengthen himself, for the souldiers did still runne daily from him, and I believe if we come to fight a great part of them will never come up to the charge. The King’s guard were gentlemen of good quality, and I heard it, that there [was] not above 40 of them which returned out of the field, this is all I shall trouble you with, what is more, you will receive [Pg 58]it from a better hand than mine: Let us pray one for another, God I hope will open the King’s eyes, and send peace to our Kingdome. I pray remember my love to all my friends; if I could write to them all I would, but for such newes I write you, impart it to them, my Leiutenant and I drinke to you all daily; all my runawayes, I stop their pay, some of them for two dayes some three dayes and some four dayes, which time they were gone from mee, and give their pay to the rest of the souldiers, two of my souldiers are runne away with their Horse and Armes: I rest, and commit you to God.

Your loving Cousin,

EDWARD KIGHTLEY.

The Rebellion in Ireland and our Battell were both the 23 of October.

he Geology of the Edge Hill region presents points of study to the

student of the physical phases of the science rather than to the

palæontologist, though it does not appear in either case that the

conditions presented are difficult to read. Beginning with the low range

of hills three miles N.W. of Kineton, forming the Trias outcrop, and

fringed with a thin development of Rhætics, we cross the broad plain of

the Lower Lias almost without undulation, save in the ridge which

stretches from Gaydon to Butler’s Marston, until the foot of Edge Hill

itself is reached. Fragments of Ammonites of the rotiformis type are

occasionally ploughed up in the plain, and the railway cutting at North

End has yielded specimens of Ammonites semicostatus. The hill slopes are

in the main formed of the clays and shales of the Middle Lias, the Zone of

Ammonites margaritatus with certain characteristic fossils, Cypricardia

cucullata, &c., appearing in the old brickyard at Arlescot. There is no

other exposure of the seleniferous shales of the zone; their course [Pg 60]is

masked by a rich belt of woodland. The natural terraces somewhat

characteristic of this horizon in the midlands are roughly developed

towards the Sun Rising, and are more perfectly shown at Hadsham hollow in

the Hornton vale. At Shenington, four miles southward, there are some

beautifully terraced fields, one locally known as Rattlecombe Slade

recalling to mind the lynchets of the Inferior Oolite sands of

Dorsetshire. They are in the main terraces of drainage, the step-like form

of subsidence being due to the composition of the seleniferous marls and

under waste. The terraces are of exceptional regularity, and run parallel

to the lines of drainage; in one case, however (Kenhill), in the same

locality, they form a bay or recess on the hill slope. A familiar instance

of the last phase is to be seen at the Bear Garden, Banbury. The salient

feature of the Edge Hill escarpment is the Marlstone rock-bed, the

uppermost division of the Middle Lias. Several sections in this zone

(Ammonites spinatus) may be seen near the Round House. It has three main

divisions: The upper red layers the roadstone, the middle of several green

hard beds called top-rag, and the lower courses of dark green softer