The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life and Public Services of James A.

Garfield, by Emma Elizabeth Brown

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Life and Public Services of James A. Garfield

Twentieth President of the United States.

Author: Emma Elizabeth Brown

Release Date: November 6, 2010 [EBook #34217]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIFE, PUBLIC SERVICES--JAMES A. GARFIELD ***

Produced by Curtis Weyant, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

BOSTON

D. LOTHROP COMPANY

32 FRANKLIN STREET

Copyright, 1881,

By D. Lothrop & Co.

More eloquent voices for Christ and the gospel have never come from the grave of a dead President than those which we hear from the tomb of our lamented chief magistrate.

Twenty six years ago this summer a company of college students had gone to the top of Greylock Mountain, in Western Massachusetts, to spend the night. A very wide outlook can be gained from that summit. But if you will stand there with that little company to-day, you can see farther than the bounds of Massachusetts or the bounds of New England, or the bounds of the Union. James A. Garfield is one of that band of students, and as the evening shades gather, he rises up among the group and says, "Classmates, it is my habit to read a portion of God's Word before retiring to rest. Will you permit me to read aloud?" And then taking in his hand a pocket Testament, he reads in that clear, strong voice a chapter of Holy Writ, and calls upon a brother student to offer prayer. "How far the little candle throws its beams!" It required real principle to take that stand even in such a company. Was that candle of the Lord afterward put out amid the dampening and unfriendly influences of a long political life? It would not be strange. Many a Christian man has had his religious testimony smothered amid the stifling and vitiated air of party politics, till[Pg vi] instead of a clear light, it has given out only the flicker and foulness of a "smoking wick."

But pass on for a quarter of a century. The young student has become a man. He has been in contact for years with the corrupting influences of political life. Let us see where he stands now. In the great Republican Convention at Chicago he is a leading figure. The meetings have been attended with unprecedented excitement through the week. Sunday has come, and such is the strain of rivalry between contending factions that most of the politicians spend the entire day in pushing the interests of their favorite candidates. But on that Lord's day morning Mr. Garfield is seen quietly wending his way to the house of God. His absence being remarked upon to him next day, he said, in reply, "I have more confidence in the prayers to God which ascended in the churches yesterday, than in all the caucusing which went on in the hotels."

He had great interests at stake as the promoter of the nomination of a favorite candidate When so much was pending, might he not be allowed to use the Sunday for defending his interest? So many would have reasoned But no! amid the clash of contending factions and the tumult of conflicting interests, there is one politician that heard the Word of God sounding in his ear "Six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work, but the seventh is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God, in it thou shall not do any work." And, at the bidding of the Divine command, his conscience marches him away to the house of God. Not, indeed, to enjoy the luxury of hearing some famous preacher, or of listening to some superb singing, but he goes to one of the obscurest and humblest churches[Pg vii] in the city, because there is where he belongs, and that is the church which he has covenanted to walk with, as a disciple of Jesus Christ. "How far" again "that little candle threw its beams!" It was a little thing, but it was the index of a principle, an index that pointed the whole American people upward when they heard of it. Here was a man who did not carry a pocket conscience—a bundle of portable convictions tied up with a thread of expediency. Nay! here was a man whose conscience carried him—his master, not his menial, his sovereign, not his servant.

And when, during the last days in his home at Mentor, just before going to Washington to assume his office, he was entertaining some political friends at tea, he did not forego evening prayers, for fear he might be charged with cant, but, according to his custom, drew his family together and opened the Scriptures and bowed in prayer in the midst of his guests. And his was a religious principle that found expression in action as well as in prayer. A lady residing in Washington told us that while a member of the House of Representatives, he was accustomed to work faithfully in the Sunday school, and that among his last acts was the recruiting of a class of young men and teaching them in the Bible. We know from his pastor that he was not too busy to be found often in the social meetings of the church, nor too great to be above praying and exhorting in the little group of Christians with whom he met. A practical Christian, did we say? He must have been a spiritual Christian also. There is one address of his in Congress that made a great impression on our mind as we read it. He was delivering a brief eulogy on some deceased Senator—I[Pg viii] think it was Senator Ferry. He spoke of him as a Christian, not a formalist, but a devout and godly disciple of Christ. And then he spoke of the rest into which he had entered, and quoted with great effect that beautiful hymn of Bonar's—

And taking the key from these last words, he said: "Yes, when the Lord comes there will be no more weeping, no more sorrow, no more death. 'Even so come, Lord Jesus.'"

We believe that only a man of real spiritual, evangelical faith could have uttered those words. And when we think how rarely such a man has filled the presidential chair, we feel overwhelmed at the loss.

Let us praise God that for once we have had a President who could shine in the most illustrious position in the nation, and yet light up for us the humblest walks of Christian obedience. Here is one who ruled and who served, who was a leader of the people and a follower of Christ. The seat where he sat as ruler of fifty millions will speak to generations yet to come, telling them how righteousness exalteth a ruler, and the little stream where he was baptized will tell perpetually, as it flows on, how it "becometh us to fulfil all righteousness."

CHAPTER I.

The "Great Heart of the People."—Bereaved of their Chief.—Universal

Mourning.—Wondering Query of Foreign Nations.—Humble

Birth in Log Cabin.—The Frontier Settlements

in Ohio.—Untimely death of Father.—Struggles of

the Family. 11

CHAPTER II.

Boyhood of James.—Attempts at Carpentry.—First Earnings.—His

Thirst for Knowledge.—The Garfield Coat-of-Arms.—Ancestry,

etc. 21

CHAPTER III.

Life at the "Black-Salter's".—James wants to go to Sea.—His

Mother will not give her Consent.—Hires out as a Woodchopper.—His

Powerful Physique.—His Strength of Character. 25

CHAPTER IV.

James still longs for the Sea.—Experience with a Drunken Captain.—Change

of Base.—Life on the Canal. 30

CHAPTER V.

Narrow Escape from Drowning.—Return Home.—Severe Illness.—James

determines to fit himself for a Teacher.—Geauga

Seminary.—Personal Appearance.—Dr Robinson's

Verdict. 36

CHAPTER VI.

Low state of Finances.—James takes up Carpentry again.—The

[Pg x]Debating Club.—Bread and Milk Diet.—First Experience

in School-Teaching.—Becomes Interested in Religious

Topics.—Creed of the Disciples.—James joins the New

Sect. 42

CHAPTER VII.

Return to Geauga Seminary.—Works at Haying through the

Vacation.—Teaches a Higher Grade of School.—First

Oration.—Determines to go to College.—He visits the

State Capitol at Columbus. 48

CHAPTER VIII.

Hiram Institute.—The faithful Janitor.—Miss Almeda Booth.—James

is appointed Assistant Teacher.—Critical habit of

Reading.—Moral and Religious Growth.—Debating Club. 53

CHAPTER IX.

Ready for College.—His Uncle lends him Five Hundred Dollars.—Why

he decides to go to Williams.—College Life. 58

CHAPTER X.

Return Home.—Appointed Professor, then President, of Hiram

Institute.—His Popularity as a Teacher.—Answers Prof

Denton.—Marriage. 67

CHAPTER XI.

Law Studies.—Becomes Interested in Politics.—Delivers Oration

at the Williams Commencement.—Elected State Senator.—His

Courage and Eloquence. 74

CHAPTER XII.

War Declared Between the North and South.—Garfield Forms a

Regiment from the Western Reserve.—Is Appointed Colonel.—General

Buell's Order.—Garfield Takes Charge of the

18th Brigade.—Jordan's Perilous Journey.—Bradley

Brown.—Plan of a Campaign.—March Against Marshall, 80

CHAPTER XIII.

Opening of Hostilities.—Brave Charge of the Hiram Students.—Giving

the Rebels "Hail Columbia".—Sheldon's Reinforcement.—The

Rebel Commander Falls.—His Army

[Pg xi]Retreats in Confusion. 93

CHAPTER XIV.

Garfield's Address to his Soldiers.—Starvation Stares them in

the Face.—Garfield Takes Command of the Sandy

Valley.—Perilous Trip up the River.—Garfield's Address

to the Citizens of Sandy Valley.—Pound Gap.—Garfield

Resolves to Seize the Guerillas.—The Old Mountaineer.—Successful

Attack.—General Buell's Message.—Garfield is

Appointed Brigadier General. 100

CHAPTER XV.

Garfield takes Command of the Twentieth Brigade.—Battles of

Shiloh and Corinth.—The Fugitive Slave.—Attack of

Malaria.—Home Furlough.—Summoned to Washington.—Death

of his Child.—Ordered to Join General Rosecrans.—Kirke's

Description of Garfield. 110

CHAPTER XVI.

Rosecrans Quarrels with the War Department.—Garfield as

Mediator.—Remarkable Military Document.—The Tullahoma

Campaign.—Insurrection Averted.—Chattanooga.—Battle

of Chickamauga.—Brave Defence of Gen. Thomas.—Garfield's

Famous Ride. 115

CHAPTER XVII.

Rosecran's Official Report.—Sixteen Years Later.—Promotion

to Major General.—Elected to Congress.—Resigns his

Commission in the Army.—Endowed by Nature and Education

for a Public Speaker.—Moral Character.—Youngest

Member of House of Representatives.—One Secret of Success.—First

Speech.—Wade Davis Manifesto.—Extracts

from Various Speeches. 125

CHAPTER XVIII.

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln.—The New York Mob.—Garfield's

Memorable Words.—Eulogy upon Lincoln.—Memorial

Oration.—Eulogy upon Senator Morton.—Extracts

from other Orations. 138

CHAPTER XIX.

The Home in Washington.—Fruit Between Leaves.—Classical

Studies.—Mrs. Garfield.—Variety of Reading.—Favorite

[Pg xii]Verses. 147

CHAPTER XX.

Tide of Unpopularity.—Misjudged.—Vindicated.—Re-elected.—The

De Golyer Contract.—The Salary Increase Question.—Incident

Related by President Hinsdale. 154

CHAPTER XXI.

The Credit Mobilier.—Garfield entirely Cleared of all Charges

Against him.—Tribute to him in Cincinnati Gazette.—Elected

U. S. Senator.—Extract from Speech.—Sonnet. 160

CHAPTER XXII.

After the Ordeal.—Unanimous Vote of the General Assembly of

Ohio.—Extract from Garfield's Speech of Acceptance.—Purchase

of the Farm at Mentor.—Description of the New

House.—Life at Mentor.—The Garfield Household.—Longing

for Home in his Last Hours. 167

CHAPTER XXIII.

Republican Convention at Chicago.—The Three Prominent Candidates.—Description

of Conkling.—Logan.—Cameron.—Description

of Garfield.—Resolution Introduced by Conkling.—Opposition

of West Virginians.—Garfield's Conciliatory

Speech.—His Oration in Behalf of Sherman.—Opinions

of the Press. 174

CHAPTER XXIV.

The Battle still Undecided.—Sunday among the delegates.—Garfield's

Remark.—Monday another Day of Doubt.—The

Dark Horse.—The Balloting on Tuesday.—Garfield's Remonstrance.—He

is Unanimously Elected on the Thirty-sixth

Ballot.—Enthusiastic Demonstrations, Congratulatory

Speeches and Telegrams.—His Speech of Acceptance. 187

CHAPTER XXV.

Return Home.—Ovations on the Way.—Address at Hiram Institute.—Impromptu

Speech at Washington.—Incident of

the Eagle.—The Tract Distributor. 196

CHAPTER XXVI.

News of the Nomination Received with Delight.—Mr Robeson

speaks for the Democrats in the House of Representatives.—Ratification

[Pg xiii]Meeting at Williams College.—Governor Long's

Opinion.—Hotly-contested Campaign.—Garfield Receives the

Majority of Votes.—Is Elected President on the Second of

November, 1880.—Extract from Letter of an Old Pupil.—Review

of Garfield's Congressional Life.—His own Feelings

in Regard to the Election. 201

CHAPTER XXVII.

At Mentor.—The Journey to Washington.—Inauguration Day.—Immense

Concourse of People.—The Address.—Sworn

into Office.—Touching Scene.—Grand Display.—Inauguration

Ball.—Announcement of the Members of the Cabinet.—Two

Great Problems.—How they were Solved.—Disgraceful

Rupture in the Senate.—Prerogative of the Executive

Office vindicated. 207

CHAPTER XXVIII.

The President Plans a Ten-Days' Pleasure-Trip.—Morning of

the Fateful Day.—Secretary Blame Accompanies him to the

Station.—A Mysterious-looking Character.—Sudden Report

of a Pistol.—The President Turns and Receives the Fatal

Shot.—Arrest of the Assassin.—The President Recovers

Consciousness and is Taken Back to the White House. 214

CHAPTER XXIX.

At the White House.—The Anxious Throngs.—Examination of

the Wounds.—The President's Questions.—His Willingness

to Die.—Waiting for his Wife.—Sudden Relapse.—A

Glimmer of Hope.—A Sunday of Doubt.—Independence

Day.—Remarks of George William Curtis. 218

CHAPTER XXX.

The Assassin.—What were his motives.—His own Confessions.—Statement

of District-Attorney Corkhill.—Sketch of Guiteau's

Early Life. 227

CHAPTER XXXI.

Night of the Fourth.—Extreme Solicitude at the White House.—Description

of an Eye-witness.—Attorney McVeagh's

Remark.—Sudden Change for the Better.—Steady Improvement.—The

Medical Attendance. 233

CHAPTER XXXII.

A Relapse.—Cooling Apparatus at the White House.—The

[Pg xiv]President writes a Letter to his Mother.—Evidences of

Blood Poisoning.—Symptoms of Malaria.—Removal to

Long Branch.—Preparation for the Journey.—Incidents by

the Way. 238

CHAPTER XXXIII.

Description of the Francklyn Cottage.—The Arrival at Long

Branch.—The President is Drawn up to the Open Window.—Enjoys

the Sea View and the Sea Breezes.—The Surgical

Force Reduced.—Incident on the Day of Prayer. 245

CHAPTER XXXIV.

Hopeful Symptoms.—Official Bulletin.—Telegram to Minister

Lowell.—Incidents at Long Branch.—Sudden Change for

the Worse.—Touching Scene with his Daughter.—Another

Gleam of Hope.—Death ends the Brave Heroic Struggle.—The

Closing Scene. 252

CHAPTER XXXV.

The Midnight Bells.—Universal Sorrow.—Queen Victoria's

Message.—Extract from a London Letter.—The Whitby

Fishermen.—The Yorkshire Peasant.—World wide Demonstrations

of Grief. 260

CHAPTER XXXVI.

The Services at Elberon.—Journey to Washington.—Lying in

State.—Queen Victoria's Offering.—Impressive Ceremonies

in the Capitol Rotunda. 266

CHAPTER XXXVII.

Journey to Cleveland.—Lying in State in the Catafalque in the

Park.—Immense Concourse.—Funeral Ceremonies.—Favorite

Hymn.—At the Cemetery. 273

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

Lakeview Cemetery.—Talk with Garfield's Mother.—First

Church where he Preached.—His Religious Experience.—Garfield

as a Preacher. 280

CHAPTER XXXIX.

The Sunday Preceding the Burial.—The Crowded Churches.—The

one Theme that Absorbed all Hearts.—Across the

Water.—At Alexandra Palace.—At St. Paul's Cathedral.—At

Westminster Abbey.—Paris.—Berlin.—Extract from

[Pg xv]London Times. 287

CHAPTER XL.

National Day of Mourning.—Draping of Public Buildings and

Private Residences.—Touching Incident.—Tributes to Garfield.—Senator

Hoar's Address.—Whittier's Letter.—Senator

Dawes' Remarks. 290

CHAPTER XLI.

Subscription Fund for the President's Family.—Ready Generosity

of the People.—Touching Incident.—Total Amount of the

Fund.—How the Money was Invested.—Project for Memorial

Hospital in Washington.—Cyrus W. Field's Gift of

Memorial Window to Williams College.—Garfield's Affection

for his Alma Mater.—Reception given Mark Hopkins and the

Williams Graduates.—Garfield's Address to his Classmates. 301

CHAPTER XLII.

Removal of the President's Remains.—Monument Fund Committee.—Garfield

Memorial in Boston.—Extracts from

Address by Hon. N. P. Banks. 306

CHAPTER XLIII.

Southern Feeling.—Memorial Services at Jefferson, Kentucky.—Extracts

from Address by Henry Watterson.—Senator Bayard.—Ex-Speaker

Randall.—Senator Hill.—Extracts from

some of the Southern Journals. 328

CHAPTER XLIV.

Extracts from some of the President's Private Letters to a Friend

in Boston, bearing the same Family Name.—To Corydon E.

Fuller, a College Classmate. 336

CHAPTER XLV.

Reminiscences of Corydon E. Fuller.—Of one of the Pupils at

Hiram Institute.—Garfield's Keen Observation.—His Kindness

of Heart.—Anecdote of the Game of Ball.—Of the

Lame Girl in Washington.—Of Brown the ex-Scout and old

Boat Companion. 353

CHAPTER XLVI.

Remarks of a Personal Friend.—Reminiscences of the President's

[Pg xvi]Cousin, Henry Boynton.—Garfield as a Freemason.360

CHAPTER XLVII.

Poems in Memory of Garfield, by Longfellow.—George Parsons

Lathrop.—From London Spectator.—Oliver Wendell Holmes.—H.

Bernard Carpenter—John Boyle O'Reilly—Joaquin

Miller.—M. J. Savage.—Julia Ward Howe.—Rose Terry

Cooke.—Prize Ode.—Kate Tannett Woods. 368

CHAPTER XLVIII.

Currency.—Lincoln.—The Draft.—Slavery.—Independence.—The

Rebellion.—Protection and Free-Trade.—Education.—William

H. Seward.—Fourteenth Amendment.—Classical

Studies.—History.—Liberty.—Statistics.—Poverty.—The

Salary Question.—The Railway Problem.—Elements of

Success.—Law.—The Revenue.—Statesmanship.—Relation

of Government to Science.—Gustave Schleicher.—Suffrage.—Union

of the North and South.—Appeal to Young

Men.—Inaugural. 388

ADDENDA.

Remarkable Military Document by Garfield 494

Official report of the post-mortem examination of Garfield's body 505

Senator Hoar's Address 520

Hon. James G. Blame's Eulogy 544

A Threnody 584

The "Great Heart of the People."—Bereaved of their Chief.—Universal Mourning.—Wondering Query of Foreign Nations.—Humble Birth in Log Cabin.—The Frontier Settlements in Ohio.—Untimely Death of Father.—Struggles of the Family.

"The great heart of the people will not let the old soldier die!"

So murmured the brave, patient sufferer in his sleep that terrible July night, when the whole nation, stricken down with grief and consternation at the assassin's deed, watched, waited, prayed—as one man—for the life of their beloved President.

And all through those weary eighty days that followed, of alternate hope and fear, how truly the great, loving, sympathetic heart of the people did battle, with millions of unseen weapons, for the strong, heroic spirit that never faltered, never gave up "the one chance," even while he whispered: "God's will be done; I am ready to go if my time has come."

Party differences were all forgotten; there was no longer any North or South—only one common[Pg 12] brotherhood, one great, sorrowing household watching with tender solicitude beside the death-bed of their loved one.

How anxiously the varying bulletins were studied! How eagerly the faintest glimmer of hope was seized! And when, on that never-to-be-forgotten anniversary of Chickamauga's battle, the midnight bells tolled out their solemn requiem,

And yet, with renewed fervor, we repeat those pathetic words:

"The great heart of the people will not let the old soldier die!"

While bowing reverently, submissively to the decree of the Almighty Disposer of human affairs, the nation feels that "no canon of earth or Heaven can forbid the enshrining of his manly virtues and grand character, so that after-generations may profit by the contemplation of them."

A halo of immortal glory already gathers around the name of James A. Garfield.

The remembrance of his brave, self-forgetting endurance of pain, his strong, indomitable will, his tender regard for his aged mother, his simple,[Pg 13] unaffected piety, his cheerful resignation, will never be effaced from the heart of the people.

And when expressions of sympathy and regret came to America from all parts of the world, the wondering query arose:

"How is it that republican manners and republican institutions can produce such a king among men as President Garfield?"

Let us go back to that humble log cabin in the wilds of Ohio where, fifty years ago, a little fair-haired, blue-eyed boy was born.

It is a bleak, bitter day in November, and the whistling of the winds through the crevices, mingles with the howl of hungry wolves in the woods close by.

But the new baby finds a warm welcome waiting him in that rough cabin home. The mother's love is fully reflected in the honest face of the great, warm-hearted father, as he folds the little stranger in his strong arms, and declares he is "worth his weight in gold."

Thomas, a boy of nine years, with Mehetabel and Mary, the two little sisters, look wonderingly upon their baby brother, and then run out to spread the good news through the neighborhood.

In those early days the frontier settlements seemed like one family, so interested were all in the joys and sorrows of each.

Eighteen months later, when the brave, strong[Pg 14] father was cut down in the midst of his work, a circle of true-hearted, sympathizing friends stood, like a body-guard, around the little family.

One of those dreaded forest fires had been raging for days through the tract of country adjoining the Garfield farm. With the aid of his older children, Mehetabel and Thomas, the father had at last checked the flames, but, sitting down to rest by the open door, he took a severe cold which brought on congestion of the throat.

Before a physician could be called he was past all human aid, and, looking wistfully upon his children and heart-broken wife, he said, with dying breath,—

"I am going to leave you, Eliza. I have planted four saplings in these woods, and I must now leave them to your care."

The blue-eyed baby, who bore his father's name, could not understand the sorrowful faces about him, and, toddling up to the bedside, he put his little hands on the cold lips, and called "Papa! Papa!" till the weeping mother bore him out of the room.

"What will become of those poor, fatherless children?" said one neighbor to another.

"It is a strange providence," was the reply. "The mother is too young and too frail to carry on the farm alone. She will have to sell everything, and find homes for the children among her friends."[Pg 15]

But Eliza Garfield was not the weak, dependent woman they had imagined. Moreover, she had one brave little helper close at hand.

"Don't cry, mother dear," said Thomas, making a great effort to keep back his own tears. "I am ten years old now, you know. I will take care of you. I am big enough to plough and plant, and cut the wood and milk the cows. Don't let us give up the farm. I will work ever so hard if we can only keep together!"

Noble little fellow! No wonder the mother's heart grew lighter as she watched his earnest face.

"You are not strong enough, dear child, to do all that," she said, "but God helping us, we will keep together. I will sell off part of the farm to pay our debts, and we shall then have thirty acres left, which will be quite enough for you and me to take care of."

It was now late in the spring, but Thomas managed to sow the wheat, plant the corn and potatoes and with the help of a kind neighbor complete the little barn his father had begun to build.

In cultivating the ground, his mother and sisters were always ready to help, and together they split the rails, and drove the stakes for the heavy fence around the wheat-field.

With such example of untiring industry and perseverance constantly before his eyes, it is no[Pg 16] wonder the restless baby brother soon tried to lend a helping hand.

"Me do it too," he would cry, when Thomas took down the rake or the hoe, and started off for his work in the fields.

"One of these days, Jimmy," the boy-farmer would reply, with a merry smile: though even then he could not help hoping there might be better things in store for the little brother he loved so dearly.

Walking all the way to Cleveland, Thomas secures a little job, and brings home his first earnings, with a bounding heart.

"Now Jimmy can have a pair of shoes," he says to his mother who cannot keep back her tears as she looks at his own bare feet.

The old cobbler comes and boards at the cabin while he makes the little shoes, and when they are completed it is hard to tell which is the happier boy,—Thomas or little Jimmy.

Four years after the father's death, a school-house is built a mile and a half away.

"Jimmy and the girls must go," says Thomas.

"Yes," replies the mother, "but I wish you could go, too."

"It wouldn't do for me to leave the farm, mother dear," says the noble boy. "One of these days, perhaps I can study at home."

The mile and a half walk to the school-house[Pg 17] was a long, hard pull for little Jimmy, in spite of those new shoes; and many a time Mehetabel might have been seen, carrying him back and forth on her broad shoulders.

It was a happy day for all the children when the new log school-house was put up on one corner of the Garfield farm. The land had been given by Mrs. Garfield, and the neighbors clubbed together and built the house, which was only twenty feet square, with a slab roof, a puncheon floor, and log benches without backs.

The master was a young man from New Hampshire. He boarded with Mrs. Garfield, and between him and little James a warm friendship was soon established.

The bright active child was never tired of asking questions.

"He will make his mark in the world, one of these days—you may take my word for it!" exclaimed the teacher, as he recounted James' wonderful progress at school.

The happy mother never forgot these words, and determined to give her little boy every possible advantage.

But the Ohio schools in those days were very poor. The three "R's," with spelling and geography, were the only branches taught, and oftentimes the teachers knew but little more than the scholars.

As soon as James could read, he eagerly devoured[Pg 18] every book that came within his reach. The family library comprised not more than half a dozen volumes, but among these, Weems' "Life of Marion" and Grimshaw's "Napoleon" were especial favorites with the eager enthusiastic boy.

Every night the mother would read to her children from her old, well-worn Bible: and oftentimes James would puzzle his little playmates with unexpected scripture questions. His wonderful memory held a strange variety of information in its tenacious grasp. He delighted to hear his mother read poetry, and would often commit long passages by heart. His vivid imagination peopled the old orchard with all sorts of strange characters. Each tree was named after some noted Indian chief, or some favorite hero he had read about; and from a high ledge of rocks in the neighborhood, he would sometimes deliver long harangues to his imaginary audiences. Thomas watched the progress of his little brother with fatherly pride and admiration, and James looked up to him with loving confidence.

He could now help about the farm in many ways, and when Thomas got an opportunity to work out and earn a few extra pennies, James would look after the stock, chop the wood, hoe the corn, and help his mother churn and milk.

"One of these days, James," she said to him, as he was working diligently by her side, "I expect[Pg 19] Thomas will go out into the world to earn his living, and then you will have to take his place here on the farm."

"But, how soon will that be, mother?" asked the little fellow, who felt then that he could not possibly get along without his big brother.

"Not until Thomas is twenty-one, and then you will be twelve years old—older by two years than Thomas was when your father died."

"I wish I could be as good a farmer as he," said James; "but I think I would rather be a carpenter."

"And I would rather have you a teacher or a preacher," said his mother; "but we must take our work just as Providence gives it to us, and farming, my boy, comes first to you."

It was a trying day to the whole family when Thomas left the little home to work on a clearing, "way off in Michigan." He would be gone six months, at least, and there was very little communication in those days between Ohio and the farther west.

"I wish you could have found work nearer home," said the fond mother.

"But I shall earn higher wages there—twelve dollars a month,"—answered the self-forgetting son; "and, when I get back, I shall have money enough to build you a frame house."

The little log cabin was fast coming to pieces,[Pg 20] and for five years Thomas had been cutting and seasoning lumber for the new house, but they had never been able to hire a carpenter to put it up.

James tried very hard to fill his brother's place, but he could never throw his whole soul into farming as Thomas had done. He read and studied all the time he could get out of working hours, and his thirst for knowledge was constantly increasing. But how was he to procure the education for which he longed?

"Providence will open the way," said the good mother; "though how and when I cannot tell."

Boyhood of James.—Attempts at Carpentry.—First Earnings.—His Thirst for Knowledge.—The Garfield Coat-of-Arms.—Ancestry, etc.

True to his promise, Thomas returned in a few months with seventy-five dollars in gold, which seemed a great sum to the little family.

"Now you shall have the new house, mother," he exclaimed; and it was not many days after, that the carpenter was hired and the work begun.

James watched the building with keen, observant eyes. Before the house was completed he had learned a good part of the trade and practised it besides.

"I think I'll have to employ you when I want an extra hand," laughed the good-natured mechanic, as he noticed how cleverly James used the mallet, chisel and plane.

"I wish you would; I like the trade," exclaimed the boy, with sudden earnestness.

After the family had moved into the new house, which consisted of three rooms below and two above, Thomas went back to his work in Michigan, and James returned to his labor on the farm.[Pg 22]

But the boy's restless spirit longed for a wider field. If he could only earn a little money, perhaps he would be able to buy a few books.

Passing the carpenter's shop one day, he saw a pile of boards at the door waiting to be planed. He stepped inside and asked for the job, which was readily given him.

"I will give you a cent a board," said the carpenter, "for I know you will do them well."

"How soon do you want them done?" asked James.

"Oh! it doesn't matter," answered the carpenter; "take your own time for them."

"All right!" said the boy, "I'll begin early to-morrow morning, just as soon as I get through with the chores on the farm."

Before night he had planed a hundred boards, and each board was twelve feet long!

He asked the carpenter to come and count them, lest he had made a mistake.

"That is too hard a day's work for a little fellow like you," exclaimed the astonished man; "but here are a hundred pennies, as I promised you."

This was the first money that James had ever earned, and it was with a proud, happy heart he emptied his load of coppers that night into his mother's lap.

It was not a difficult matter to find jobs after that. A boy who could plane a hundred boards[Pg 23] in a day was just the sort of help the enterprising carpenter wanted. Not long after, he engaged James to help him put up a barn, paying him about twenty dollars for the job.

By this time James had learned about all he could in the district schools. He had performed problems in arithmetic that puzzled his teachers, and could repeat by heart the greater part of his reading books. A copy of "Josephus" came into his hands, and he read it over and over until long passages were indelibly impressed upon his memory.

"Robinson Crusoe," "Alonzo and Melissa," he devoured that winter with all a boy's enthusiasm, and the little home in Orange seemed smaller to him than ever. He longed to go out into the world and find a wider sphere of labor. The blood of his old Welsh ancestors was burning in his veins. He had often looked at the old Garfield coat of arms, which his father had kept with loyal pride, and wondered what it meant. Now he seemed to understand, as if by a sudden intuition, the crimson bars on the golden shield, with that strong arm, just above, wielding a sword, whose motto read, "In cruce vinco."

"Tell me about my great-great-grandfathers," he said one day to his mother, as they were sitting together by the open fire.

"Your father's family came from Wales," she[Pg 24] answered, "and the first James Garfield was one of the brave knights of Gaerfili Castle. But that is going a long way back. I know your father used to say he was more proud of having an ancestor who had fought in the Revolutionary War, and that was Solomon Garfield, your own great-grandfather."

"How splendid it is to be a soldier!" exclaimed James.

"Yes," said his mother, "but there are many grand victories won in the world besides those upon the battle-field."

And just here it may be said that it was not only from his father's side that James Garfield inherited so many sterling traits of character. His mother is a descendant of Maturin Ballou, a French Huguenot, who joined the colony of Roger Williams, and settled in Cumberland, Rhode Island. From this pioneer preacher, a great many eminent men have sprung, among them the celebrated Hosea Ballou, a cousin of Eliza Ballou Garfield.

Life at the "Black-Salter's".—James wants to go to Sea.—His mother will not give her Consent.—Hires out as a Woodchopper.—His Powerful Physique.—His Strength of Character.

About ten miles from the little settlement at Orange, and not far from Cleveland, was a large potash factory, owned by a certain Mr. Barton. The neighboring farmers, when they cleared their lands, would draw the refuse logs and branches into a great pile and burn them. The ashes thus collected, they sold to this Mr. Barton, who went by the name of "black-salter," because the potash he manufactured was called in its crude state, "black salts." At one time he needed a new shed where the ashes were leached, and James assisted the carpenter who put it up.

The bright, industrious lad pleased the old black-salter, and he offered him fourteen dollars a month, if he would come and work in his ashery.

This was two dollars more than Thomas was earning "away off in Michigan," and James was greatly delighted at the prospect of earning one hundred and sixty-eight dollars a year!

It was not, however, just the sort of work he[Pg 26] would have chosen; and the mother dreaded for her son the rough companionship of the black-salters.

But James did not associate with the rude, coarse men out of working-hours. Their profanity shocked him; and he gladly turned to the books he found on an upper shelf at Barton's house.

As might have been expected, however, these books were very different from any he had read before. "Marryatt's Novels," "Jack Halyard," "Lives of Eminent Criminals," and "The Pirate's Own Book," were in fact more dangerous companions for him than the coarse, brutal men would have been. The printed page carried with it an authority that the excited boy did not stop to question. He would sit up all night to follow in imagination some reckless buccaneer in his wild exploits, till at last an insatiable longing to be a sailor fired his brain.

"A life on the ocean wave" seemed to him, at that time, the "ultima thule" of all his dreams. He longed to see some more of the world, and to the inexperienced lad this seemed the quickest and surest way.

One day, he happened to hear Mr. Barton's daughter speak of him in a sneering tone as her father's "hired servant." This was more than the high spirit of James could bear. Years after, he said to a friend,[Pg 27]—

"That girl's cutting remark proved a great blessing to me. I was too much annoyed by it to sleep that night; I lay awake under the rafters of that old farm-house, and vowed, again and again, that I would be somebody; that the time should come when that girl would not call me a 'hired servant.'"

The next morning James informed his employer that he had concluded to give up the black-salter's business.

In vain Mr. Barton urged him to stay, by the offer of higher wages.

Much as he needed the money, the boy was determined to find some other and more congenial way of earning a living. If he could only go to sea!

Fortunately none of the family favored this wild scheme of James.

His mother declared that she could never give her consent. "If you ever go to sea, James," she said in her firm, decided tones, "remember it will be entirely against my will. Do not mention the subject to me again."

James was a dutiful son. He did not want to oppose his mother's will, and yet he did want to go to sea.

A few days after he heard that his uncle, who was clearing a large tract of forest near Cleveland, wanted to hire some wood-choppers. After talking the matter over with his mother, he decided to[Pg 28] offer his services. He could not be idle, and wood-chopping was certainly preferable to leaching ashes.

His sister Mehetabel, who was now married, lived near this uncle, so James could make his home with her.

Altogether the plan pleased Mrs. Garfield, although she was loath to part with her boy, even for a few months.

James engaged to cut a hundred cords of wood for his uncle, at the rate of fifty cents a cord, and declared he could easily cut two cords a day.

Now it so happened that the edge of the forest where James' work lay overlooked the blue waters of Lake Erie. With stories from "The Pirate's Own Book" still haunting his brain, it was not strange that he often stopped in his work to count the sail, and watch the changing color of the beautiful waters.

By and by he noticed that the old German by his side, who seemed to wield his axe so slowly, was getting ahead of him in the amount of work accomplished. He began to realize that he was wasting a deal of time by these "sea dreams," and resolutely turned his back upon the fascinating waters.

It was not so easy, however, to drive out of his mind the bewitching sea-faring tales he had read; and when those hundred cords of wood were cut,[Pg 29] he returned home with the old longing to be a sailor only intensified.

He said nothing, for he did not wish to grieve his mother, and as it was now the last week in June he hired himself out to a farmer for the summer months, to help in haying and harvesting.

James was now a strong, muscular boy in his teens. He possessed, naturally, a fine constitution, and his simple life and vigorous exercise in the open air had greatly enhanced his powers of endurance. Whatever he undertook he was determined to carry through successfully. His strong, indomitable will conquered every difficulty, while his stern integrity was a constant safeguard.

James still longs for the Sea.—Experience with a Drunken Captain.—Change of Base.—Life on the Canal.

James went on with his work at home, attending school in the winter, reading whatever books he could find, and taking odd jobs in carpentry to add to the family income.

His heart, however, was still on the sea.

At last he said to his mother:

"If I should be captain of a ship some day, you wouldn't mind that, would you?"

Now Mrs. Garfield, like a wise mother, had been studying her restless boy and was not unprepared for this returning desire on his part "to follow the sea."

"You might try a trip on Lake Erie," she replied, "and see how you like it; but if you want to be 'somebody,' as you say, I would look higher than to a sea-captain's position."

James hardly heard his mother's last words, so delighted was he to have this unexpected permission.

He packed up his things as quickly as possible and walked the whole distance to Cleveland.[Pg 31]

Boarding the first schooner he found lying at the wharf, he asked one of the crew if there was any chance for another hand on board.

"If you can wait a little," was the answer, "the captain will soon be up from the hold."

James had a very exalted idea of this important personage; he expected to see a fine, noble-looking man such as he had read about in his books.

Suddenly, he heard a fearful noise below, followed by terrible oaths. Stepping aside to let the drunken man pass him, he was greeted by the gruff question,—

"What d'yer want here, yer green land-lubber, yer?"

"I was waiting to see the captain," replied James.

"Wall, don't yer know him when yer do see him?" he shouted. "Get off my ship, I tell yer, double quick!" James needed no second invitation. Could this besotted brute be a specimen of the monarchs of the sea? The boy was so shocked and disgusted that he made no further effort to find a place on board ship. He began to think his story-books might be a little different from the reality in other things as well as captains!

Wandering through the city, he came to the canal which at that time was a great thoroughfare between Lake Erie and the Ohio river. One of the boats, called the "Evening Star," was tied to the bank, and James was greatly surprised to[Pg 32] find that the captain of it was a cousin of his, Amos Letcher.

"Well, James, what are you doing here?" said the canal-boat captain.

"Hunting for work," replied the boy.

"What kind of work do you want?"

"Anything to make a living. I came here to ship on the lake, but they bluffed me off and called me a country greenhorn."

"You'd better try your hand on smaller waters first," said his cousin; "I should like to have you work for me, but I've nothing better to offer you than a driver's berth at twelve dollars a month."

"I must do something," answered James, "and if that is the best you can offer me, I'll take the team."

"It was imagination that took me upon the canal," he said, years after; and it is easy to see how fascinating the trips from Cleveland to Pittsburgh seemed at that time to the inquiring boy.

The "Evening Star" had a capacity of seventy tons, and it was manned, as most of the canal-boats were, with two steersmen, two drivers, a bowsman, and a cook. The bowsman stood in the forward part of the boat, made ready the locks, and threw the bow-line around the snubbing-post. The drivers had two mules each, which were driven tandem, and, after serving a number of hours on the tow-path, they took turns in going on board with their mules.

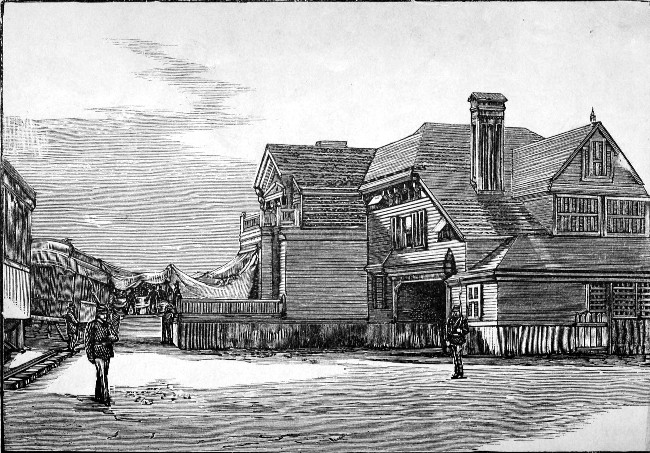

On the Tow-Path.

On the Tow-Path.

James had hardly taken his place behind "Kit and Nance," as his team was called, when he heard the captain call out,—

"Careful, Jim, there's a boat coming." The boy had seen it, and was trying to pass it to the best of his ability. But his inexperience and haste occasioned a sudden tightening of the reins, and, before any one quite knew what had happened, both driver and mules were jerked into the canal. For a few seconds it seemed as if they would go to the bottom, but James was equal to the emergency, and, getting astride the forward mule, kept his head above water until rescue came. This was his initiation in canal-boat driving, and the adventure was a standing joke among his comrades for a long time.

When they came to the "Eleven-Mile Lock," the captain ordered a change of teams, and James went on board with his mules.

Letcher, who is still living in Bryan, Ohio, gives the following account of his talk with the boy as they were passing the locks:

"I thought I'd sound Jim on education—in the rudiments of geography, arithmetic and grammar. For I was just green enough in those days to imagine I knew it all. I had been teaching school for three months in the backwoods of Steuben County, Indiana. So I asked him several questions, and he answered them all; and then he asked[Pg 34] me several that I could not answer. I told him he had too good a head to be a common canal-hand."

One evening when the "Evening Star" was drawing near the twenty-one locks of Akron, the captain sent his bowsman to make the first lock ready. Just as he got there, a voice hailed him through the darkness. It was from a boat above that had reached the locks first.

"We are just around the bend," said her bowsman, "all ready to enter."

"Can't help it!" shouted the bowsman of the "Evening Star," with a volley of oaths; "we've got to hev this lock first!"

The captain was so used to these contests on the canal that he did not often interfere, but it was a new experience to James. He tapped his cousin Amos on the shoulder, and said,—

"Does that lock belong to us?"

"Well, I suppose not, according to law," was the answer, "but we will have it, anyhow."

"No! we will not!" he exclaimed.

"But why?" said the captain.

"Why?" he repeated, "because it don't belong to us."

Struck with the boy's sense of right, and ashamed of his own carelessness, the captain called out to his men,—

"Hold on, hold on! Let them have the lock."

When the boatmen knew that their fight had[Pg 35] been prevented by James's interference they were greatly incensed, and began to call him "coward" and all sorts of derogatory names.

The boy only smiled; he knew he could vindicate his rights when the time came, and it was not long before he had an opportunity.

The boat had just reached Beaver, and James was on deck with his setting-pole against his shoulder; a sudden lurch wrenched it from him and threw it upon one of the boat-hands, who was standing close by.

"Beg pardon, Dave," said the boy quickly; "it was an accident."

The great, rough man, however, would take no apology, and rushed upon James with clenched fists. A fight seemed inevitable, but with one well-directed blow, the boy of sixteen threw down his burly antagonist, and held him fast.

"Pound him, James! Give him a good thrashing!" exclaimed the captain.

"Not when he is down and in my power," said the boy. Then, letting his conquered foe rise, he said,—

"Come, Dave, give us your hand!" and from that time forth they were the best of friends.

"He's dif'rent from the rest on us—that's sartin—but he's a good un, got a mighty sight o'pluck," said the whole crew.

Narrow Escape from Drowning.—Return Home.—Severe Illness.—James determines to fit Himself for a Teacher.—Geauga Seminary.—Personal Appearance.—Dr Robinson's Verdict.

One dark, stormy night, just as the "Evening Star" was leaving a long reach of slack water, James was called out of his berth to tend the bow-line. As he began to uncoil the rope, it caught on the edge of the deck; he pulled several times before he could extricate it, but suddenly it gave way with such force as to throw him headlong into the water.

The whole crew were soundly sleeping, the boat glided over him, and as he could not swim he felt there was no hope. Suddenly he caught hold of something hard; it was the rope which had become entangled in a crevice of the deck and become so tight that it was an easy matter to climb up by it into the boat.

As he stood there in his dripping clothes, rescued from a watery grave, he took the rope and tried to see how it happened to catch in the crevice. Six hundred times he threw it, but it would not kink in the same manner again.[Pg 37]

"No one but God could have saved my life by such a thread as that!" he exclaimed, and then he began to wonder if he could not make a better use of his miraculously-spared life than by spending it upon a canal-boat.

A severe attack of chills and fever followed this night's drenching and exposure. He thought of his mother and her hopes for him, and made up his mind to return home as soon as he was able.

His mother was overjoyed when, a few weeks later, he stood before her and told her of his changed plans. But again the malaria asserted its sway over him, and for a long time he lay between life and death. It was six months before he was able to do anything, and then to his mother's delight he told her he was going to fit himself to be a teacher.

A young man named Samuel Bates (now a clergyman in Madison, Ohio,) had charge that winter of the district-school in Orange. He was a frequent visitor at Mrs. Garfield's, and between James and himself there sprang up a warm friendship. The young teacher had attended the Geauga Seminary in Chester, and was full of his school experiences. He told James how economically one could live, by clubbing together with other students, and the result was that in the following spring, Garfield and his two cousins, William[Pg 38] and Henry Boynton, went to Chester and rented a room just across the street from the seminary. The house belonged to a poor widow, who agreed to look after their room and do their washing for a small sum. They bought their own cooking-stove, and immediately set up house-keeping. James had only eleven dollars in his pocket, but he hoped to earn more before that was gone.

The academy was a plain wooden building of three stories, and could accommodate about a hundred pupils. The library connected with it contained a hundred and fifty volumes, which seemed to James a perfect mine of wealth. Among the pupils at that time attending the academy was a studious young girl by the name of Lucretia Rudolph, but the boys and girls seldom saw each other except in their classes, and James was so shy and awkward he did not care much for the society of young ladies. He watched Miss Rudolph, however, with quiet admiration. Her sweet face, her pleasant manners, and fine scholarship, made her a universal favorite, and little by little a hearty friendship sprang up between the two students who had so many aims in common.

The principal of the academy at that time was an eccentric old gentleman by the name of Daniel Branch. His wife, who was his chief assistant[Pg 39] and equally eccentric, was trying to introduce into the school a grammar of her own construction, which was totally at variance with all other systems. For instance, she insisted that but should be parsed as a verb, in the imperative mood, with the sense of to be out; she also declared that and was another verb in the imperative mood, and meant add!

Young Garfield, who had been thoroughly drilled in Kirkman's Grammar at the district school, constantly contended against these new ideas which, to his clear, well-balanced brain, presented nothing but absurdity. It is to be hoped that the other scholars followed his sage example, and that Branch's idiosyncrasy was soon banished from the school curriculum.

James' personal appearance at this time is thus described by one of his friends:

"His clear, blue eyes, and free, open countenance were remarkably prepossessing. His height was exaggerated by the coarse, satinet trousers he wore, which were far outgrown, and reached only half-way down the tops of his cowhide boots. It was his one suit, and the threadbare coat was so short in the sleeves that his long arms had a singularly awkward look. His coarse, slouched hat, much the worse for wear, covered a shock of unkempt yellow hair that fell down over his shoulders like a Shaker's."[Pg 40]

Without consulting any one, James resolved to be examined by a physician before going on with his studies.

He went to Dr. J. P. Robinson, of Bedford, who happened to be in the neighborhood, and said to him,—

"You are a physician, and know the fibre that is in men. I want you to examine me, and then say frankly whether or no it is worth while for me to take a course of liberal study. It is my earnest desire to do so, but if you advise me not to attempt it, I shall feel content."

The doctor, in speaking of this incident, says:—

"I felt that I was on my sacred honor, and the young man looked as though he felt himself on trial. I had had considerable experience as a physician, but here was a case much different from any other I had ever had. I examined his head, and saw that there was a magnificent brain there. I sounded his lungs, and found them strong and capable of making good blood. I felt his pulse, and saw that there was an engine capable of sending the blood up to the brain. I had seen many strong, physical systems with warm feet, but cold, sluggish brain; and those who possessed such systems would simply sit around and doze. At the end of a fifteen minutes' careful examination of this kind, we rose, and I said: 'Go on; follow the[Pg 41] promptings of your ambition. You have the brain of a Webster, and you have the physical proportions that will back you in the most herculean efforts. Work, work hard, do not be afraid of overworking; and you will make your mark.'"

Low State of Finances.—James Takes up Carpentry again.—The Debating Club.—Bread and Milk Diet.—First Experience in School-Teaching.—Becomes Interested in Religious Topics.—Creed of the Disciples.—James Joins the New Sect.

After buying his school-books and some other necessary articles, James found his small amount of funds rapidly decreasing. But this did not discourage him in the least.

"I have never yet had any difficulty in finding work, and I don't believe I shall now," he said to his cousins, as he started off one Saturday afternoon to find a carpenter's shop.

In those days planing was always done by hand, and Mr. Woodworth, the one carpenter at Chester, was very glad to engage so willing and capable an assistant as the young student.

By working at his shop before and after school, and all day upon Saturday, James earned enough money to pay all his bills that term, and carry home a few dollars besides. From that time forward he never failed to pay his own way, although to do it he was obliged to work very hard and deny himself many comforts.[Pg 43]

The studies of his first term at Chester included English grammar, natural philosophy, arithmetic and algebra. It was one of the regulations of the school to write a composition every fortnight upon subjects chosen sometimes by the principal, and sometimes by the students themselves. These essays were occasionally read before the whole school, and the first time that James read his, he trembled so that he was "very glad," he writes, "of the short curtain across the platform that hid my shaking legs from the audience."

In the Debating Society James always took an active part. He was a little diffident at first, but soon astonished himself as much as his friends by his ready command of language. Whatever question came up before the club he studied as he would a problem in mathematics. The school library supplied him with books of reference, and his ready memory never failed him. The students at Geauga listened with astonishment to the eloquent appeals of their rough, ungainly schoolmate. The secret of his power was largely due to the thorough preparation with which he armed himself. He was so full of his subject he could not help imparting it in the strongest and most impressive manner. Here it was that he laid the basis of his future success as a public speaker.

Having taken from the library the "Life of Henry C. Wright," he became quite interested in[Pg 44] the author's experiment of living upon a bread and milk diet. He told his cousins they had been too extravagant in their mode of living, that milk was better than meat for students, and that another term they must try it.

The boys, always ready to follow James, acquiesced; and after a trial of four weeks, found their expenses had been reduced to thirty-one cents each, per week. But their strength also had become reduced; and while still making milk their principal article of diet, they concluded to increase their table to the amount of fifty cents each for the remainder of the term.

When the long vacation came James was very anxious to teach school. The principal at Geauga had told him that he was fully competent, and with his usual energy and determination he started out to find a school.

"What! you don't expect we want a boy to teach in our district?" was the first reply to his modest application.

It was of no use to show the committee his excellent recommendation from Mr. Branch—they wanted a man, not a boy.

Somewhat discouraged, James walked on to the next district, only to find that a teacher had already been engaged. About three miles north was another school, but here, too, they were just supplied with a graduate from Geauga.[Pg 45]

Two days of persistent school-hunting followed, but James was unable to find any position as teacher.

"It may be that Providence has something better in store for you," said his mother; but James was so tired and discouraged he had not a word to say.

Early next morning he was surprised by a call from one of the committee men belonging to their own district.

"We want some one to teach at the 'Ledge,'" he said to James, "and we heard that you were looking for a school. Now, the boys all know you in this district, and they are a pretty hard lot to manage, but I reckon you are stout enough to thrash them all."

Not a very encouraging outlook for James, surely! But after talking the matter over with his Uncle Amos Boynton, he concluded to undertake the school.

Beginning as "Jim Garfield," he determined to win the respect of both pupils and parents until he was known as "Mr. Garfield." To do this a deal of firmness was required, and his first day at school was a series of battles with naughty boys. After that a most friendly relation was established between pupils and teacher. They felt he had no desire to domineer over them, but that he would maintain order and decorum at any cost. In[Pg 46] "boarding around," as was the custom for district school teachers in those days, he became well acquainted with all the families in the neighborhood and gained a still firmer hold upon the affections of his pupils. Before the winter was over, Mr. Garfield had won the reputation of being "the best teacher who had ever taught at the 'Ledge.'"

It was a great delight to his mother to have him so near her. Every Sunday he spent at home, and it was at this time that he became deeply interested in religious questions. His mother was a member of the Church of Disciples, or Campbellites, as they were sometimes called, from Alexander Campbell, the founder of the sect.

Their creed is as follows:

I. We believe in God, the Father.

II. We believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God, the only Saviour.

III. That Christ is a Divine Being.

IV. That the Holy Spirit is the Divine agent in the conversion of sinners, and the sanctification of Christians.

V. That the Old and New Testament Scriptures are the inspired word of God.

VI. That there is future punishment for the wicked, and future reward for the righteous.

VII. That the Deity is a prayer-hearing and prayer-answering God.

VIII. That the Bible is our only creed.[Pg 47]

The founder of the sect was for a long time a member of the Baptist Church, and declared that he differed from them only in his "disbelief in the binding force of the church creed, and in the necessity of ministerial ordinations."

The new church grew very rapidly, notwithstanding the persecutions it received from both the Baptist and Freewill Baptist denominations, and it numbers now over half a million members.

It is not strange that James was drawn to this single-hearted, struggling sect of "Disciples." The earnest, persuasive arguments of one of its preachers led him to Christ, and when, that same winter, he was baptized in the little river at Orange, he became at once an earnest champion of the new church. In all religious discussions, he claimed the right of following the Bible according to the convictions of his own conscience, and declared that every one else should have the same right.

His consistent Christian life added strength to his spoken words, and the Disciples felt that a bright and shining light had been added to their ranks.

Return to Geauga Seminary.—Works at Haying through the Vacation.—Teaches a higher Grade of School.—First Oration.—Determines to Go to College.—He visits the State Capitol at Columbus.

When James returned to the academy, he made an arrangement with Mr. Woodworth, by which he could have a comfortable boarding-place at one dollar and six cents a week. This was at Mr. Woodworth's own house, and the payment was to be taken out in labor at the carpenter's shop. It was an excellent plan, and gave James more time for his studies, in spite of the hard manual labor he performed out of school-hours. He could use the square and the scratch-awl now, as well as the plane; and his wages were correspondingly increased.

In the summer vacation of his third term at Geauga, James and a schoolmate resolved to earn a little money at haying. They accordingly hired themselves out to a neighboring farmer who wanted some extra hands. Noticing how vigorously the boys worked, the farmer turned to his men and said,—

"Lookee here, you lubbers! these boys are[Pg 49] gitting way ahead of you. They make broader swaths, and they mow a sight better than you do!"

When the haying was done, and the settling day came, the farmer asked the boys what wages they expected.

"Whatever you think is right," replied James.

"Wall," said the farmer, "as yer only boys, of course yer won't expect men's wages."

"But didn't you say yourself," argued James, "that we did more work than your men? If that is so, why should you pay us less?"

The farmer was nonplussed, and gave the boys the same wages he paid his men, remarking, as he did so,—

"It's the fust time I ever paid boys so much, but you've fairly earned it—that's a fact!"

It was just about this time that the anti-slavery contest began to assert itself throughout the country.

In the little Debating Club at Geauga, the question was given out, "Ought slavery to be abolished in this republic?" It was a subject that roused James to his best efforts; and his school-mates, as they listened to his fiery denunciations against slavery, declared that "Jim ought to go to Congress!"

The following winter James procured a school at Warrensville, where he was paid sixteen dollars[Pg 50] a month and his board, which was more than he had ever earned before. It was in this school that one of the pupils wanted to take up geometry—a branch of mathematics that James had never studied.

As usual, however, he was equal to the emergency. Buying a text-book, he studied geometry after school-hours, until he had mastered the science, and his pupils never once dreamed but that he was as familiar with it as with algebra or arithmetic.

It was at the annual exhibition of Geauga Seminary, in November, 1859, that James delivered his first oration. It was prepared with his usual carefulness, and delivered with so much magnetic earnestness that the whole audience were held spell-bound.

"He is bound to make his mark in the world," said every one who had listened to the earnest, enthusiastic student.

Mrs. Garfield noted with grateful joy that her son no longer spoke of "going to sea." The one great aim of his life now was to procure a liberal education. A deeper, broader ocean was stretching out before him, and already his pulses thrilled with the mighty, incoming tide.

It was during his last term at Geauga Seminary that James met a young man who was a graduate of a New England college. From him he learned[Pg 51] that it was possible to work one's way through college as well as through school. It was a new thought to James. His poverty had seemed to him before an insurmountable obstacle in gaining a university education. Now, he began to study Latin and other branches that might pave the way to a college examination.

On his return home, he found his mother was just about to start on a journey to Muskingum County, where some of her relatives lived. She was very anxious that James should go with her, and, when he found that he could obtain a school near Zanesville, he was quite ready to go. The Cleveland and Columbus Railroad had just been opened, and this was James' first ride in the cars. When they reached Columbus they visited the legislature, which was then in session; and, as James remarked afterwards, "That alone was worth a month's schooling to me."

The mother and son spent three months in this part of Ohio, James teaching the little school at Harrison, and studying hard himself all the time. Having met a student from the Eclectic Institute at Hiram, Portage County, Ohio, he learned that opportunities were there afforded for studying the branches of the first two college years. The expenses of tuition were no greater than at Geauga Seminary, and the Institute was under the direction of the Church of the Disciples.[Pg 52]

It seemed a providential opening, and, after talking over the matter with his mother, he determined to seek admission there the following autumn.

Hiram Institute.—The faithful Janitor.—Miss Almeda Booth.—James is appointed Assistant Teacher.—Critical habit of Reading.—Moral and Religious Growth.—Debating Club.

It was towards the latter part of August, 1851, and James was nearly twenty years of age when he first presented himself at Hiram Institute. The board of trustees was then in session, and he was directly introduced into the room where they were seated. Notwithstanding his shabby clothes and awkward manners, his earnest, intelligent face at once prepossessed them in his favor.

"I must work my way," he began; "but I am very anxious to get an education. I thought, perhaps, you would let me ring the bell and sweep the floors to pay part of my bills."

"How do we know that you can do the work well?" asked one of the trustees.

"If, at the end of a couple of weeks," replied James, "you find that my work does not suit you, I will not ask to keep the place."

"I think we had better try the young student," said another of the trustees, and so the question was settled, and James was duly installed as janitor.[Pg 54]

The town of Hiram was at that time twelve miles from the railroad, and consisted of a straggling collection of houses, with two churches and a few stores at the cross-roads. Its natural advantages, however, were wonderfully fine, and to-day it is sometimes called "the crown of Ohio." Its location is very near the line where the waters divide, one part flowing northward to Lake Erie, the other southward to the Ohio river.

The Institute was a plain, brick building on the top of a hill, whose slopes were thickly planted with corn; from this eminence a charming panorama of the whole surrounding country could be obtained. It was built for the special accommodation of the sons and daughters of the Western Reserve farmers, and among its founders was Mr. Zebulon Rudolph, the father of James' old school-mate, Lucretia Rudolph. The Rev. A. S. Hayden was, at this time, its principal, and Thomas Munnell and Norman Dunshee were assistant teachers.

The aims of the school were,—

1st. To provide a sound, scientific and literary education.

2d. To temper and sweeten such education with moral and scriptural knowledge.

3d. To educate young men for the ministry.

Hiram College, Hiram, Ohio.

Hiram College, Hiram, Ohio.

The charter of the Institute, according to the peculiar tenet of the religious movement in which it originated, was based upon the study of the Holy Scriptures. The Disciples believed that the Bible ought to take a larger place in general culture than had as yet been accorded to it. In the course of study, the system pursued was strictly elective. It was just the place for James to fit for college, and pursue, if he chose, branches that would enable him to enter a university two years in advance.

Among the pupils at Hiram, when James entered the Institute, was a Miss Almeda Booth, some nine years his senior, who proved an invaluable friend and helper. She was a teacher as well as scholar, but James, at the end of a few months, found himself pursuing the same studies and ranking in the same classes as Miss Booth. "I was far behind her," he writes, "in mathematics and the physical sciences, but we were nearly in the same place in Greek and Latin."

Miss Booth was a lady of rare talent. Upon the death of the young man to whom she was engaged, she resolved to consecrate her life to higher intellectual attainments, in order to increase her usefulness.

In a tribute to her memory, a few years ago, Garfield said,—

"She exerted a more powerful influence over me than any other teacher, except President Hopkins.... The few spare hours which schoolwork left us were devoted to such pursuits as[Pg 56] each of us preferred, but much study was done in common. I can name twenty or thirty books, which will be doubly precious to me because they were read and discussed in company with her. I can still read between the lines the memories of her first impressions of the page, and her judgment of its merits."

Whenever James had a thesis to prepare, he would talk over the subject for hours with Miss Booth, and together they read during one term a hundred pages of Herodotus and a hundred of Livy.

At the close of his first year at Hiram, James was given the position of assistant teacher of the English department and ancient languages. He had also secured regular work with the carpenter in Hiram, so it was no longer necessary for him to serve as janitor. But many of his old schoolmates still remember the faithfulness with which he performed the menial services of his first position. He was promptness itself at the ringing of every bell, and seemed the personification of Herbert's servant, in making "drudgery divine"—for truly,

It was while at Hiram Institute that he formed the habit of taking critical notes from all the books he read. It proved of invaluable service to him in[Pg 57] after years, for no matter upon what topic he desired to speak, these indexes served as so many finger-posts in his library, and directed him at once to the subject-matter in hand.

All this time the moral and religious faculties of the young student were developing no less rapidly than his intellectual powers. At the frequent meetings of the Disciples he was a ready speaker, and his earnest appeals are remembered to this day by his school-mates. Every one seemed to think, as a matter of course, that he would become a preacher in the Church of the Disciples, but, as the months went by, he seemed disinclined to express any decision upon that point.

The Debating Club at Hiram called out his best powers. His practice at Geauga had fitted him to express his opinions upon whatever subject might be under discussion, in the clearest and most impressive manner. At one time the contest over some public question became so bitter and excited that James finally rose and declared he would no longer waste his time over such nonsensical things as the majority proposed. A division of the club was the final result, and James was chosen president of the new society.

Ready for College.—His Uncle lends him Five Hundred Dollars.—Why he Decides to go to Williams.—College Life.

After spending three years at Hiram in faithful, persistent study, James felt he was prepared to enter the junior class at almost any college. But how was he to procure the means to carry on his studies? Thus far he had defrayed all his expenses by his own exertions as janitor, carpenter, and teacher; but, to enter college, he would need a little money in advance. His proud, independent spirit shrank from borrowing even from his friends. At last, he went to his uncle, Thomas Garfield, and asked for the use of five hundred dollars until he could earn enough money by teaching to pay it back.

His uncle Thomas had always shown a kindly interest in his efforts to obtain an education, and now gladly advanced him the sum he desired. In order to make sure the payment in case of his death, James procured a policy upon his life to the value of five hundred dollars, and presented it to his uncle.

He had now, as he thought, the necessary means[Pg 59] to enter college, but which of the many inviting doors should he enter? Every one seemed to take it for granted that he would go to Bethany College; which was under the patronage of his own denomination, but, in a letter to a friend, he gave his final decision as follows:—

"After thinking it all over, I have made up my mind to go to Williamstown, Mass.... There are three reasons why I have decided not to go to Bethany:—1st. The course of study is not so extensive or thorough as in eastern colleges. 2d. Bethany leans too heavily toward slavery. 3d. I am the son of Disciple parents, am one myself, and have had but little acquaintance with people of other views; and having always lived in the West, I think it will make me more liberal both in my religious and general views and sentiments, to go into a new circle, where I shall be under new influence. Therefore, I wrote to the presidents of Brown University, Yale and Williams, setting forth the amount of study I had done, and asking how long it would take me to finish their course.

"Their answers are now before me. All tell me I can graduate in two years. They are all brief, business notes, but President Hopkins concludes with this sentence: 'If you come here we shall be glad to do what we can for you.' Other things being so nearly equal, this sentence, which[Pg 60] seems to be a kind of friendly grasp of the hand, has settled that question for me. I shall start for Williams next week."

It was at the close of the summer term in 1854 that James presented himself before President Hopkins for examination. He is described at this time "as a tall, awkward youth, with a great shock of light hair, rising nearly erect from a broad, high forehead, and an open, kindly, and thoughtful face, which showed no traces of his long struggle with poverty and privation."

He passed the examination without difficulty, and soon became a great favorite with his class in spite of his shabby clothes and Western provincialisms. "Old Gar" and the "Ohio giant" were the names by which he was best known in college, and a classmate says of him that "he immediately took a stand above all his companions for accurate scholarship, and won high honors as a writer, reasoner, and debater."

The beautiful, mountainous scenery about Williamstown was a constant delight to the young Westerner. He would frequently climb to the top of Greylock and feast his eyes upon the magnificent panorama below. He was no longer obliged to work at the carpenter's bench, or perform the duties of janitor, and these long walks gave him needful exercise as well as pleasant recreation.

President Hopkins became greatly interested in[Pg 61] the earnest, enthusiastic student. The "friendly hand-grasp" was extended to him in many ways, and, when the summer vacation came, he offered him the free use of the college library.

James gladly availed himself of this privilege, and browsed among the books to his heart's content. It was the first time in his life that he had ever found leisure to read the works of Shakespeare, consecutively. During the summer vacation he not only read and thoroughly studied the plays, but committed large portions of them to memory. He also varied his heavier reading with works of fiction, allowing himself one novel a month. Dickens and Thackeray were favorite authors, and Tennyson's poems were read with ever-increasing pleasure.

He completed his classical studies the first year he was at Williamstown, as he had entered far in advance of the other pupils. He then took up German as an elective study, and, in the space of a few months, had made such rapid progress that he could read Goethe and Schiller, and converse with fluency.

In the "Williams Quarterly," a magazine published by the students, James took great interest, and was a frequent contributor both in prose and poetry.

The following poem, entitled "Memory," he wrote the last year he was at Williams College:[Pg 62]—

He was also a prominent member of the Philologian Society, of which he was afterwards elected president.

While James was at Williamstown, the anti-slavery contest was at a white heat. Charles Sumner had aroused the whole nation by his stirring, eloquent speeches in Congress; and when the tidings came of the attack made upon him by Preston Brooks of South Carolina, indignation meetings were held everywhere throughout the North. At the gathering in Williamstown, Garfield made a most powerful speech, denouncing slavery in the strongest terms.

"Hurrah for 'Old Gar!'" exclaimed his classmates; "the country will hear from him yet!"