Leo the Circus Boy

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Leo the Circus Boy

Author: Ralph Bonehill

Release Date: April 10, 2011 [EBook #35821]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEO THE CIRCUS BOY ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I.—A ROW AND ITS RESULT.

- CHAPTER II.—CAPTURING A RUNAWAY LION.

- CHAPTER III.—LEO LEAVES THE FARM.

- CHAPTER IV.—LEO JOINS THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH.

- CHAPTER V.—A LEAP OF GREAT PERIL.

- CHAPTER VI.—LEO ASSERTS HIS RIGHTS.

- CHAPTER VII.—LEO GAINS HIS LIBERTY.

- CHAPTER VIII.—AMONG THE CLOUDS IN A THUNDERSTORM.

- CHAPTER IX.—THE MAD ELEPHANT.

- CHAPTER X.—CAPTURING THE ELEPHANT.

- CHAPTER XI.—A CRIMINAL COMPACT.

- CHAPTER XII.—THE STOLEN CIRCUS TICKETS.

- CHAPTER XIII.—LEO MAKES A CHANGE.

- CHAPTER XIV.—LEO MAKES A NEW FRIEND.

- CHAPTER XV.—AN ACT NOT ON THE BILLS.

- CHAPTER XVI.—AN UNPLEASANT POSITION.

- CHAPTER XVII.—CARL SHOWS HIS BRAVERY.

- CHAPTER XVIII.—A WONDERFUL TRICK EXPLAINED.

- CHAPTER XIX.—WAMPOLE’S NEW SCHEME.

- CHAPTER XX.—ANOTHER STOP ON THE ROAD.

- CHAPTER XXI.—AN UNEXPECTED BATH.

- CHAPTER XXII.—WAMPOLE SHOWS HIS HAND.

- CHAPTER XXIII.—THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH ONCE MORE.

- CHAPTER XXIV.—IN THE CIRCUS RING AGAIN.

- CHAPTER XXV.—ANOTHER BALLOON TRIP.

- CHAPTER XXVI.—ADVENTURES AMID THE FLAMES.

- CHAPTER XXVII.—ESCAPE FROM THE BURNING FOREST.

- CHAPTER XXVIII.—THE RIVAL BALLOONISTS.

- CHAPTER XXIX.—PORLER’S MOVE.

- CHAPTER XXX.—MART KEENE’S STORY.

- CHAPTER XXXI.—A FALL FROM THE CLOUDS.

- CHAPTER XXXII.—MART A PRISONER.

- CHAPTER XXXIII.—LEO TO THE RESCUE.

- CHAPTER XXXIV.—THE END OF PORLER.

- CHAPTER XXXV.—A COWARDLY ATTACK.

- CHAPTER XXXVI.—ON THE ELEVATED TRACKS.

- CHAPTER XXXVII.—THE CAPTURE OF GRISWOLD.

- CHAPTER XXXVIII.—GOOD-BY TO THE CIRCUS BOY.

Leo the Circus Boy

CHAPTER I.—A ROW AND ITS RESULT.

“Land sakes alive, Daniel, look at that boy!”

“Where is he, Marthy?”

“Up there on the old apple tree a-hangin’ down by his toes! My gracious, does he wanter kill himself?”

“Thet’s wot he does, Marthy,” grumbled old Daniel Hawkins. “He’ll do it, jest so ez we kin pay his funeral expenses. Never seen sech a boy before in my born days!”

“Go after him with the horsewhip, Daniel. Oh! goodness gracious, look at thet now!”

And the woman, or, rather, Tartar, Mrs. Martha Hawkins, held up her hands in terror as the boy on the apple tree suddenly gave a swing, released his feet, and, with a graceful turn forward, landed on his feet on the ground.

“Wot do yer mean by sech actions, yer young good-fer-nothin’?” cried Daniel Hawkins, rushing forward, his face full of sudden rage. “Do yer want ter break yer wuthless neck?”

“Not much, I don’t,” replied the boy, with a little smile creeping over his sunburned, handsome face. “I’m afraid if I did that I would never get over it, Mr. Hawkins.”

“Don’t try ter joke me, Leo Dunbar, or I’ll break every bone in your worthless body!”

“I’m not joking; I mean what I say.”

“Did yer put the cattle out in the cherry pasture?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Feed the pigs?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Mend thet barn door! as I told yer to yesterday?”

“Mended it last night.”

“Wot about fixin’ thet scythe yer broke tudder day?”

“I can’t fix that. I’ll have to take it down to Joe Marks’ blacksmith shop.”

“O’ course! An’ who’s goin’ ter pay fer it?” demanded Daniel Hawkins.

“You can take it out of my wages, Mr. Hawkins.”

“Out o’ yer wages?”

“That’s what I said, sir.”

The old farmer’s face grew darker than ever. “Ain’t no wages comin’ to yer! You spile more than yer earn.”

“According to my reckoning there are about twenty-eight dollars coming to me,” returned Leo Dunbar quickly. “I have kept the tally ever since I came to live with you.”

“Ain’t a cent, boy; not a penny.”

“I beg to differ with you. And now while we are at it, Mr. Hawkins, supposing we settle up?”

“Eh?”

“I say, supposing we settle up?”

“Settle up?” repeated the miserly farmer in amazement.

“Yes. You can pay me what you owe me. My month will be up to-morrow, and I don’t intend to stay here any longer.”

“But yer will stay, boy! I’ve got a right on yer. The poorhouse folks signed the papers.”

“Squire Dobb signed the papers, but to me that doesn’t count. He never had any claim on me.”

“He settled yer father’s estate.”

“I know it—and kept me out of my money, too.”

“You—you——”

“No more compliments, Mr. Hawkins. I say he kept me out of my money, and I mean it. And now he and you are doing about all you can to make me commit suicide.” “Oh! jest to hear thet boy!” burst in Mrs. Hawkins, who had just come up. “Daniel, why don’t yeou birch him?”

“I will, ef he gives me any more sass,” replied her husband. “He shan’t talk about me an’ the squire.”

The old farmer was getting red in the face. He knew that Leo Dunbar was telling the truth.

A year before, Leo’s parents had died, leaving the boy alone in the world.

Mr. Dunbar’s property had been very much involved, and Squire Dobb, the most rascally lawyer in Hopsville, had taken the matter in charge.

At the end of six months he had announced to Leo that there was no money coming to him. Then, as manager of the poorhouse of the district, the lawyer had bound Leo over to Daniel Hawkins at four dollars a month and found.

“I will talk,” cried Leo spiritedly. “I think it about time that I received my rights.”

This remark made Daniel Hawkins’ wrath boil over. He ran toward the barn and presently returned, carrying a heavy hide-bound whip.

“You ain’t had a dressing down in a month, an’ now I’m a-goin’ ter give it to yer good!” he exclaimed, as he raised the whip and rushed at Leo.

Whiz! The heavy whip came down, the blow aimed for the boy’s shoulder.

But Leo was not hit. Like a flash he moved to one side at the last instant, and the whip only circled through the empty air.

More enraged than before Daniel Hawkins rushed forward again and caught the boy by the arm.

“You whelp! I’ll show you!” he snarled.

Again the whip was raised. But it never struck the blow intended, for an interruption came as terrorizing as it was unexpected.

There was a fearful roar out in the dusty road beyond the house, a roar that echoed and re-echoed among the hills around, and then a huge beast bounded over the stone fence, landing directly at Leo Dunbar’s feet.

It was a lion that had escaped from “The Greatest Show on Earth,” the circus that was to perform at Hopsville that afternoon and evening.

CHAPTER II.—CAPTURING A RUNAWAY LION.

If Leo Dunbar was startled at the sudden appearance of this mighty monarch of the forest, what shall be said of Daniel Hawkins and his wife, Martha?

The farmer and his spouse gave one look and then stood, fairly paralyzed with fear.

They were unable to utter a word, and, to tell the truth, they both felt as if judgment was about to fall on them for ill-treating Leo, and that the ends of their miserable lives were at hand.

The lion crouched low, moving his heavy tail slowly from side to side.

He had escaped from his steel cage but an hour before, and as yet hardly knew what to do with his freedom.

From the road he had not been able to see the persons in the yard. But he had heard their voices, and his brute nature had caused him to leap the stone fence that he might rend some living creature limb from limb.

That the lion was in an ugly humor was easy to see. His mane was ruffled, his immense claws unsheathed, and his eyes were full of blood-curdling ferocity.

At first he gazed at Leo, but then swiftly turned toward Mrs. Hawkins, taking a single leap that brought him at the woman’s very feet.

“Oh! Daniel, save me!” she managed to gasp.

“Can’t nohow, Marthy!” spluttered the old farmer.

And then, recovering just sufficiently to move, he made a wild dash for the farmhouse, leaving his wife to her fate.

“You coward!” cried Leo, but Daniel Hawkins paid no heed to the remark. It is likely that in his terror he did not hear it.

“Save me, Leo!” went on the woman. “The beast is goin’ ter eat me up!”

The sound of her voice appeared to anger the lion still more.

His tail moved quicker, and Leo saw that he was on the point of leaping on the woman.

The leap once made it would be impossible to do anything for Mrs. Hawkins. The lion would simply rend and devour her.

Leo gazed about him for some weapon. He realized that if anything was to be done it must be done instantly.

His eyes fell on the whip the old farmer had dropped. With a rapid movement he picked up the article, and, whirling around, struck the lion fairly and squarely across the eyes.

It was a telling blow, and, smarting with pain, the brute let out a roar ten times louder than before.

Then he turned about and faced Leo.

“Run for your life!” sang out the youth to the woman. “Run, I tell you!”

She stared at him, but when he gave her a shove she realized what he was saying, and made such a spurt as had never before been seen in that dooryard.

The lion watched her go, but made no attempt to follow. His mind was on Leo and on the blow the boy had given him.

He was an ugly brute, and around the circus was known to be the most difficult to manage. Trainer after trainer had tried to break him in, but without effect. Instead of getting more docile, he grew worse.

In his former days he had killed a man, and evidently he was longing for a chance to repeat this bloody tragedy.

He took several steps and tried to get behind Leo.

But the boy was on the alert and ran backward toward the apple tree.

Then the lion crouched for a leap. His immense body was bent low, his tail gave a quiver, and forward he shot toward the very spot where Leo was standing.

But as the lion leaped so did the boy. He turned a graceful curve to the left, out of the brute’s reach, and caught the lowest branch of the tree behind him.

The lion’s nose struck the tree trunk, and he let out another roar of mingled pain and disappointment.

“Didn’t do it that time,” muttered Leo. “What’s the use of banging your nose like that?”

Another roar was the only answer, and then the lion left the vicinity of the tree and moved back several yards beyond the branch to which Leo clung.

The boy knew what was coming, and immediately stood up on the limb.

He was none too soon.

Again the lion made a leap upward.

He reached the limb, but only to find that Leo had taken a spring to the next above.

But now an accident happened which neither the boy nor the brute was expecting.

The apple tree was old and somewhat rotted at the roots. The weight of the boy and the sudden shock from the heavy body of the lion were too much for it to stand.

There was a crack and a loud snap, and then the tree went over on the ground, carrying Leo and the lion with it.

The lion was completely bewildered by the fall, and, moreover, he was entrapped for the moment by several limbs which came down on his back and neck.

As the tree went over, Leo turned around and landed on his feet directly beside the lion.

He saw how mixed up the brute was amid the branches and this gave him a sudden idea.

With a lightness of foot that was surprising in a mere farm lad, he ran to the woodshed.

Soon he reappeared carrying a wash-line, a well-rope, and half a dozen leather straps.

He fastened an end of the wash-line to one of the limbs of the tree and then to another, and so on all around the lion.

Then he crossed the well-rope over the line, and even fastened it around the lion’s left hind leg.

Then making a noose of the longest strap, he watched his chance and dropped it over the brute’s neck.

Of course, the lion roared and struggled to free himself, but Leo was too quick for him.

The noose around his neck, Leo tightened it considerably, and then fastened the end of the strap to the tree trunk.

“Now, if you move you’ll take the whole tree with you,” thought the boy.

CHAPTER III.—LEO LEAVES THE FARM.

The savage lion was a prisoner.

In vain he tried to release himself. Turning over merely tangled him up tighter, and in his struggle he almost broke a hind leg and choked himself to death.

He tried to run, and succeeded in carrying the whole apple tree several yards.

But the load was too much for him, and, with a roar of pain and rage, he at length became quiet.

In the meanwhile Daniel Hawkins and his wife had gone into the farmhouse and locked all the doors and lower windows.

They were now at an upper window watching proceedings.

“He’s got him, Daniel!” cried Mrs. Hawkins.

“The apple tree is down!” groaned the old farmer in reply. “Plague take the pesky critter!”

“Leo hez tied him fast!”

“Maybe he might git away an’ chew him up. Wish he would,” continued Daniel Hawkins.

“It must be a lion from thet circus at Hopsville, Daniel, an’ if so, they’ll come after him.”

“Well, they better take him away,” growled the old farmer.

While they were talking a loud shouting was heard on the road, and presently half a dozen men on horseback came into view.

All were heavily armed, and several carried lassoes and ropes.

They were a party from the circus on the search for the lion.

Leo heard them coming and ran down the road to meet them.

“Hi, boy! Seen anything of a lion around here?” asked the leader.

“Indeed I have,” laughed Leo.

“Where is he?” demanded another of the crowd quickly.

“Over in the dooryard of that farmhouse.”

“Has he hurt any one?”

“He has scared the wits out of that man and his wife,” and Leo pointed to Daniel Hawkins and his spouse.

“He’s enough to scare the wits out of any one,” put in another of the crowd. “Come, boys, now for a tussle with old Nero.”

“We ought to shoot him at once. We can’t capture him alive,” growled a rear man.

“You won’t have to shoot him,” said Leo, with a twinkle in his eye.

“Why not? You don’t mean to say he’s dead already?”

“Oh, no! He’s alive enough.”

“Is it possible he has been captured?”

“Yes, I captured him and tied him to a tree.”

“Nonsense, boy, this is no time for fooling. The lion may eat somebody up.”

“I’m not fooling, sir. I have captured him. If you don’t believe me, come and see for yourself.”

Still incredulous, the party of men followed Leo into the dooryard.

When they saw the lion under the fallen apple tree they did not know whether to laugh, or praise Leo the most.

“By Jove! but this is the greatest feat yet!”

“Old Nero has a cage around him now and no mistake.”

“He can’t move a step unless he drags the whole tree with him!”

“Say, boy, who helped you do this?”

“No one.”

“You did it entirely alone?”

“Yes, sir,” was the modest reply.

“Thet ain’t so; it wuz me as captured yer lion fer yer,” came from Daniel Hawkins, who had joined the party in the yard.

“Mr. Hawkins, how can you say that!” exclaimed Leo in amazement. “You ran for your life and locked yourself in the house, even before your wife got away.”

“Tain’t so. I captured the lion, an’ if there’s any reward it comes to me.”

“We have offered no reward, but we are willing to pay for the capture,” replied the leader of the circus men. “But if you caught the lion how is it you were up in the house when we rode up?”

“Daniel! Daniel!” shrieked Mrs. Hawkins, still in the window. “Come up again! Leo didn’t fasten him tight enough an’ he’s gettin’ away!”

The alarm again terrorized Daniel Hawkins.

Forgetting all about his assumed bravery, he made a wild dash for the cottage, leaving Leo and the men alone in the yard.

“Does that look as if he had much to do with catching him?” laughed Leo.

“No, it does not. But the woman is right. Nero is getting ready to struggle for freedom. Come, boys, put the harness over him while we have the chance.”

The three circus men set to work. It was a dangerous proceeding, but at last it was finished and the escaped lion was a prisoner.

Then one of the men rode back to the circus grounds to return with the cage in which the brute belonged.

While this was going on, Daniel Hawkins again came out, this time followed by his wife.

He tried to convince the circus men that he had captured the lion, but no one would believe him.

“I reckon the credit goes to this boy,” said Barton Reeve, the manager of the menagerie attached to the “Greatest Show on Earth.”

“No sech thing. He only got the ropes fer me.”

“If you were so brave, what made you run just now?”

“I—I—went ter help my wife. She—she sometimes hez fits, an’ I was afraid she would git one and fall from the winder.”

All the circus men laughed at this explanation, but not one believed it true.

“An’ another thing, thet apple tree hez got ter be paid for,” continued the farmer.

“We’ll pay for that if the lion pulled it down.”

“He certainly did,” put in Mrs. Hawkins.

“Well, what was the old tree worth?”

“Fifty dollars an’ more.”

“Hardly,” put in Leo. “You said only day before yesterday you were going to cut it down for firewood, because it was so rotted.”

“Shet up, boy!” howled Daniel Hawkins. “The tree is wuth fifty dollars an’ more.”

“I’ll pay you ten dollars,” said Barton Reeve.

“You’ll pay fifty.”

“Not a cent over ten. The tree is not worth five.”

“I’ll have the law on yer fer trespass!”

“All right; if you want to sue, I guess we can stand it,” was the circus man’s cool response.

Daniel Hawkins talked and threatened, but all to no purpose.

At last he agreed to take ten dollars and two tickets for the evening performance, and the bargain was settled on the spot.

It was not long after that that the steel-caged circus wagon came along, followed by a crowd of men and boys, all eager to see the strange sights connected with an escaped lion.

It was noised about that Leo Dunbar had captured the savage brute, and the boys gazed at the farm lad enviously.

“He’s a brave one, eh?” said one.

“I wouldn’t do it for a thousand dollars, would you?” added another.

“I always knew he was a cool one, and there isn’t a fellow around as limber as he is,” put in a third.

And so the talk ran.

When the lion was safe in the cage once more, Barton Reeve turned to Leo.

“Can you come with me to the circus grounds?” he asked. “I would like to talk with you.”

“Certainly,” replied Leo quickly. “I was going up there at the first chance I got to get away from the farm, anyway.”

“Going up to see the show?”

“Not only that, but to see the manager.”

“What do you want to see the manager for?”

“I want to strike him for a job.”

“What sort of a job?”

“As a gymnastic clown.”

“A clown and a gymnast,” said Barton Reeve slowly. “Well, you might be a clown, if you got funny, but what do you know about gymnastics?”

“Quite a bit, sir, if I do say it myself. I have liked the exercise all my life, and it seems to me I was cut out for that sort of life.”

Leo’s earnestness kept Barton Reeve from smiling

He had often had boys and even men come to him full of silly notions about joining the circus.

He saw that Leo was a level-headed youth, and he noted, too, that the boy’s body was finely formed and well developed.

“See here, what do you think of this?” suddenly cried Leo.

Running forward, he turned several handsprings and ended with a clear air somersault.

“That’s all right.” In fact, it was first-rate.

“If I had the apparatus I would like to show you what I can do on the bar and with the rings,” went on Leo.

“You can do that at the grounds. Come on.”

Barton Reeve rode off, with Leo behind him on the horse.

Daniel Hawkins tried to call the boy back, but all to no purpose.

“Has he any claim on you, Leo?” asked the man.

“Not a bit of a claim. He treated me like a dog, and now I’m going to leave him whether I get in with the circus or not.”

CHAPTER IV.—LEO JOINS THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH.

On the way to the circus grounds Leo told Reeve much about himself.

He was seventeen years old, and for years had had a nice home with his parents, and it was during this time that he had taken a thorough course of gymnastics.

His father had been a retired officer of the United States army, and was supposed to be well to do at the time of his death.

But Leo had never gotten a cent out of the estate, and since becoming an orphan had known nothing but hard work.

The boy was satisfied that Squire Dobb was keeping him out of his money, but he had no proofs to use in bringing a case against the rascally lawyer.

Life on the farm he could not endure, and it was only the hope of getting some money out of Daniel Hawkins which had kept him so long at the drudgery there.

Now he was satisfied there was no money to be had, and he intended to leave at the first chance.

By the time Leo’s story was told the party had arrived at the circus grounds.

It was afternoon, and already the great white tents were up, covering an entire block in the southern end of the town.

The cage was properly placed in the menagerie department, and then Barton Reeve led the way between numerous empty wagons to the rear of a large affair used as a ticket office.

This was not yet open, but a knock on the door brought a quick response.

Two men were in the wagon, the treasurer, Mr. Giles, and Adam Lambert, the traveling manager of the show.

“Here is a young man who would like to see you, Mr. Lambert,” said Barton Reeve, and he introduced Leo.

“What is it?” asked the manager shortly. “My time is valuable.”

“He would like a job in the ring.”

And then Reeve told about what Leo had done and what the boy’s aspirations were.

Ordinarily the manager would not have listened to such an application, having hundreds of such made to him every week.

But he liked Leo’s looks, and besides, a boy who could capture a lion was certainly worth talking to.

“Don’t you know it’s a hard life, my boy?” he said.

“I’ll warrant it is no harder than life on the Hawkins’ farm, sir.”

“It’s not as rosy as it looks from a seat outside of the oval.”

“I know that. But I am willing to put up with the roughness just for the chance to make something of myself,” returned Leo.

Adam Lambert thought for a moment.

“Come with me into the ring,” he said.

Leo followed him gladly.

The rings, two in number, were empty, and so were the hundreds of seats, making the tent look vast and gloomy.

“Now show me what you can do.”

“Yes, sir.”

Off came Leo’s coat vest, and shoes. Then followed a number of handsprings, forward, backward, and sideways, and somersaults and curious attitudes.

“Can I use that bar up there?”

“Certainly, but there is no rope to get to it.”

“Never mind, sir.”

As he spoke Leo ran to the centerpole, and up this he went like a flash.

Then he gave a sudden leap and sat down on the bar several yards off.

“By Jove, there is something in that boy!” murmured Adam Lambert to Reeve. “He has just daring enough to succeed.”

“So I would say, Mr. Lambert. Hullo! Look there!”

Leo was turning rapidly on the bar.

He went through a dozen gymnastic movements, and then slid down the center pole.

“That will do,” shouted the manager. “I’ll give you a trial. You can place yourself under Dick Pomeroy, the head tumbler and bar man. Mr. Reeve, take him to Dick.”

Adam Lambert had scarcely spoken when a tall, finely-built fellow rushed into the ring from one of the dressing-rooms.

“Mr. Lambert!”

“Well, Dick.”

“Broxton is intoxicated again!”

“Indeed! Didn’t you warn him as I told you?”

“Yes, but it did no good. He is so intoxicated he can’t stand.”

“Then he can’t do his brother clown act with Snipper?”

“No, sir, we’ll have to cut it out.”

“Too bad, with Nash on the sick list, too.”

“See here,” put in Barton Reeve. “This boy wanted to do clown as well as acrobatics.”

“Is that so, Dunbar?”

“Yes, sir, if I can help you out I’ll do my best.”

“It’s short notice,” mused Adam Lambert.

“Snipper can instruct him and cut out anything difficult,” suggested Barton Reeve.

He had taken a strong liking to Leo and wished to get the boy a place.

“Well, fix it up, Dick, the best you can,” said the manager. “I must go back and see about those stolen tickets.”

And off went the manager, followed a minute later by Barton Reeve, leaving Leo alone with Dick Pomeroy, who had charge of the clowns and tumblers connected with the “Greatest Show on Earth.”

Pomeroy at once led Leo around to a dressing-room. In a corner sat Jack Snipper, a clown and gymnast, his face drawn down.

“Here’s a man to take Broxton’s place,” explained Pomeroy.

“Why, he’s a boy!” exclaimed Snipper.

“Never mind, you must drill him in the best you can.”

“Can he do anything on the bar?”

“I reckon so.”

“I don’t like this drilling in new fellows every couple of weeks,” growled Snipper, who was not a man of cheerful disposition.

As a matter of fact, he was what is commonly called a crank, and very jealous of his reputation.

He told Leo where he could obtain a pair of tights and a clown’s outfit, and made up the boy’s face for him.

Then he gave Leo a long lesson.

The two were to do a clown act, and then, while on the bars, throw off their clown dresses, and go in for a brothers’ gymnastic act.

Leo worked hard, and by the time the circus commenced he was ready to go on, although it must be admitted he was extremely nervous.

The grand entrée was the first thing on the programme. It included the rulers of all nations, savage tribes, elephants, camels, chariots, and a hundred and one other things impossible to mention.

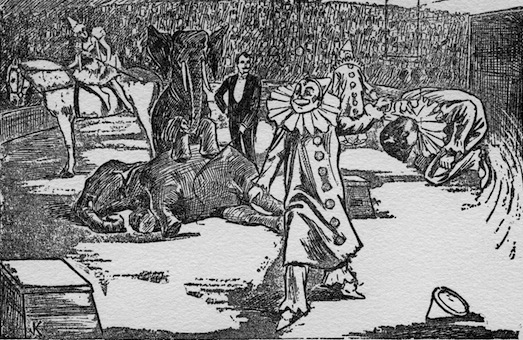

“Come on now!” suddenly said Snipper, and then he and Leo ran out into the ring and fell down and bounced up as if they were a couple of rubber balls.

“Ho! ho! look at those two clowns!” shouted the crowd.

The tumble over, the clowns chased each other around the ring, knocked each other down, and did a dozen other funny things.

While the two clowns were cutting their capers a young lady bareback rider rode into the ring.

Her name was Natalie Sparks, but she was known on the bills as Natalie the Fire Queen.

Her great act was to dive through numerous hoops of fire while on horseback.

As she began to perform, Leo commenced to climb the centerpole of the tent, doing so in a way that nearly choked the crowd with laughter.

“See him twisting like a monkey!”

“He ain’t a clown at all! See, he is throwing off his clown dress!”

“Now he is dressed in tights!”

It was true. Leo was in full gymnastic costume and was swinging gracefully from the high bar.

As Leo began to do his best on the bar, Natalie the Fire Queen started to leap through rings of fire held up by several ringmen.

The performances of the young gymnast and the Fire Queen were in full swing when a cry of horror arose.

In some unaccountable manner the fire from the hoops had communicated to the tarred ropes running up by the centerpole to the roof.

The great canvas had taken fire in several places.

Before Leo could realize what had happened a cloud of smoke seemed to envelop him.

The fire had reached the ropes supporting the very bar upon which he was performing!

His escape in that direction was cut off, and the distance to the ring below was fully half a hundred feet!

CHAPTER V.—A LEAP OF GREAT PERIL.

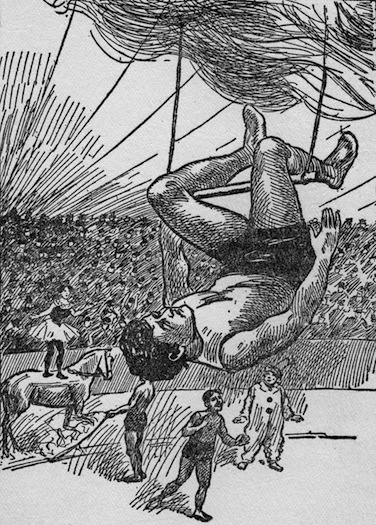

Leo fully understood his great peril.

The entire canvas above him was in flames, and in a very short while the ropes which supported the bar upon which he had been performing would be burned through.

And then? Leo hardly dared to think of the consequences. The sawdust ring below seemed a terrible distance away.

A leap to it would mean broken limbs, perhaps death.

A panic arose among the audience.

“He can’t escape!”

“He must fall or jump!”

A rope and a net were sent for, but long before they arrived Leo had made a move to save himself.

The smoke rolled around him a second time.

It was fearfully thick, and made him close his mouth and eyes for fear of being either blinded or suffocated.

As the smoke swept back in another direction there was a snap above.

One of the ropes which held the bar had parted!

The end of the bar hung down, and below it the end of the burned rope.

As quick as a flash Leo slid down to the very end of the rope.

Thus suspended he began to swing himself back and forth.

Soon he gave an extra swing, just as the smoke again came down.

Like a curving ball he passed through the cloud, past the centerpole, and on to the rings, on the other side of the tent.

He caught hold of one of the rings and hung fast.

Then after a pause in which to catch his breath he let himself down to the ground.

A deafening cheer arose.

Leo had actually saved himself from death, for as he touched the sawdust the heavy ash bar high above fell with a crash, just missing those who came on with the net.

“He’s safe!”

The ushers and others now ran around asking the vast audience to leave the tent as quietly as possible.

But every one was afraid of the falling of the huge centerpole, and all made a great rush for the openings.

In this stampede many women and children were knocked down, and it was a wonder that some of them were not killed.

The fire brigade of the circus went to work as speedily as possible. The nearest hydrant of water was some distance away, but soon a hose was attached and a stream poured on the burning canvas.

In less than half an hour the excitement was over. Without delay the canvasmen went to work to repair the damage done.

A good many people grumbled at not having seen a full performance. To these were given tickets of admission to the evening performance.

With the others from the ring, Leo hurried to the dressing tent. It was not long before he was joined by Barton Reeve.

“A great leap, my boy,” said the manager of the menagerie. “I never saw anything so neat.”

“It was a big undertaking,” smiled Leo. “I don’t think I would care to try it at every performance—at least not yet.”

“It would be the hit of your life to have that on the bills,” put in Natalie Sparks.

“Oh, that wasn’t so very wonderful,” remarked Jack Snipper, the brother clown and gymnast.

“It wasn’t, eh?” cried Reeve. He could easily see how jealous Snipper was of the attention bestowed upon Leo. “I’ll wager you a round hundred dollars you can’t make the leap with the rings ten feet closer.”

“Stuff and nonsense!” cried Snipper; but all noticed that he did not take up the offer and moved away a second later.

“You want to keep one eye on Snipper,” was Natalie’s caution to Leo.

“Why?”

“Can’t you see he doesn’t fancy the attention you are getting?”

“Oh, I’m sure I don’t want to cut short his popularity,” exclaimed the boy gymnast quickly.

“Popularity!” The Fire Queen burst into a laugh. “You can’t, Leo.”

“Why?”

“Because he never was popular. Why, they used to call him Sour Snipper.”

It was now announced that the afternoon performance would not go on, and the different people separated to take off their ring dresses and put on their everyday clothes.

Leo was rather slow to make the change. He began to practice around the tent on several turns which as yet were difficult for him to do gracefully.

“You must love to work,” growled Snipper on seeing him.

“I love the exercise,” returned Leo shortly.

“You won’t catch me doing any more of that than I have to.”

“I want to become perfect.”

“Do you mean to say by that that I am not perfect?” growled Snipper.

“We never get really perfect, Snipper.”

“Oh, pshaw! Don’t preach to me. Do you know what I think you are?”

“I do not.”

“A country greeny with a swelled head.”

Leo’s face flushed at this. A laugh came from behind the canvas, where other performers were undressing.

“Thanks for the compliment, Snipper. I may be a little green, but at the same time I’ll tell you what you can’t do.”

“What?”

“You can’t stunt me. I’ll do everything you do, and go you one better.”

“Oh, you’re talking through your hat,” growled Snipper.

“Am I? Take me up and see.”

“I won’t bother with you, you greenhorn.”

“Because you are a braggart and nothing else,” retorted Leo, stung by the insolent acrobat’s manner.

With a cry of rage, Jack Snipper leaped toward the boy, picking up a heavy Indian club as he did so.

CHAPTER VI.—LEO ASSERTS HIS RIGHTS.

At once a crowd of performers surrounded the pair. Very few of them liked Jack Snipper, and they wondered what Leo would do should the gymnast attack the boy.

“Call me a braggart, will you!” roared Snipper.

“Don’t you dare to touch me with that club!” replied Leo calmly.

“I’ll teach you a lesson!”

And, swinging the Indian club over his head, Jack Snipper made a savage blow at the young gymnast.

Had the stick struck Leo the boy’s head would have sustained a severe injury.

But as quick as a flash Leo dodged, and the Indian club merely circled through the empty air.

“For shame, Snipper!”

“Do you want to kill the boy?”

“What harm has he done?”

And so the cries ran on.

“Mind your own affairs!” shouted the maddened gymnast. “I’m going to teach the boy a lesson!”

Again he sprang at Leo.

But now suddenly the Indian club was caught. A dexterous twist, and it went flying out of reach across the dressing tent.

Then, before Snipper could recover, he received a stinging slap full in the face that sent him staggering backward on the grass.

A shout of approval went up.

“Good for Leo!”

“That’s right, boy, stand up for your rights!”

The shout brought Adam Lambert, the general manager, to the scene.

No sooner had he appeared than all the performers walked away. It was against the rules to fight, and every one present was liable to a heavy fine.

With the crowd went Snipper, who rolled over and over until a neighboring canvas-wall hid him from view.

“Who is fighting here?” demanded Lambert severely.

“Jack Snipper attacked me with an Indian club and I knocked him down,” replied Leo.

“Why did he attack you?”

“Snipper’s jealous of the lad,” came from behind a side canvas.

“Yes, the boy only stood up for his rights,” said another voice.

“We want no fighting here, Leo Dunbar,” said Lambert. “Another such scene and you may be discharged.”

And off went the general manager to inspect the mending of the tent.

He might have spoken even more severely, but he had seen Leo’s wonderful leap and realized what fine mettle there was in the lad.

Snipper remained out of sight, nor did he appear again until the evening performance.

Having finished changing his clothing, Leo walked outside and mingled with the crowd of town people.

He knew but few of them, as since he had worked on Daniel Hawkins’ farm he had been to Hopsville but seldom.

He wandered around to the museum, or side show, and while looking at the gigantic pictures displayed, was rather taken aback to see Daniel Hawkins and his wife standing not two yards away.

“My gracious!” murmured Leo to himself, and he lost no time in moving back.

As will be remembered, Daniel Hawkins had received two tickets for the show from the men who had come after the escaped lion.

Under pretense of looking for Leo, the old couple, who generally spoke of all shows as works of the evil one, attended the afternoon performance.

They saw the young gymnast, but the paint on his face as a clown so disguised him that neither recognized their bound boy.

They were much disappointed to have the fire cut short what proved to be so entertaining to them, but the extra tickets for the evening performance soothed their feelings greatly.

“We’ll take in this ’ere side show and then git a bite an’ wait fer the next openin’,” said Daniel. “It’s better’n goin’ over to the county fair.”

And Mrs. Hawkins agreed with him.

As soon as Leo saw the old couple an idea entered his head.

At the Hawkins’ farmhouse he had several things which he wished to get. Not clothing—he was too poor to own more than what was on his back—but mementos of former days, when he had had as nice a home as any lad in the Hopsville district.

These mementos were secreted in the garret of the old farmhouse, in a corner behind the wide chimney, where Daniel Hawkins had never looked for them.

“I’ll visit the house while they are here and get those things,” Leo said to himself, and off he started.

As we know, it was quite a distance. Leo looked around for some sort of a vehicle which might give him a “lift,” but unfortunately none appeared in sight.

At last he reached the place, to find it tightly locked up below.

In a twinkle Leo was up on the kitchen shed. From there he clambered along the gutter of the addition until he reached the window of a middle room.

As he had surmised this window was unlocked, and he crawled inside, although not without difficulty and danger of breaking his neck by a fall.

No sooner had he entered than a most appetizing smell greeted his nose.

“Huckleberry pie!” he cried. “By criminy! but I must have a piece!”

Down the stairs went Leo. The pies set on the kitchen table, two in number. A third, partly gone, rested close at hand.

At first Leo thought, just out of mischief, to cut a fresh pie. But then he reflected that this might cause suspicion and trouble, and he let the whole pies alone and satisfied himself on a juicy portion of that which was cut.

A glass of milk washed down the pie, and then, feeling much refreshed, the boy hurried upstairs to the garret.

The mementos were done up in a flat pasteboard box. There were pictures of his mother and father and other relatives, and half a dozen letters and other things, including a silver watch.

Daniel Hawkins had always wanted the watch but Leo had never let on that he possessed it.

With the articles in his pockets Leo started downstairs once more.

He had just reached the second story and was on the point of descending the lower flight of stairs, when an unexpected sound greeted his ears.

Daniel and Martha Hawkins had returned.

“So much cheaper ter git supper ter hum,” he heard Mrs. Hawkins say, speaking from the kitchen.

“It’s a pity, though, yer Aunt Mariah wasn’t hum,” returned Daniel Hawkins.

Leo was startled.

“Caught!” he muttered to himself, and then added: “Not much!”

With great caution he left the hallway and entered the side bedroom.

As noiselessly as possible he opened the window again.

The distance to the ground was at least twelve feet, but there was heavy grass below, and Leo did not mind such a drop.

“It’s nothing to that leap I had to take in the circus,” he said to himself, and crawled out on the window-sill.

“Hi! hi! You young rascal! What are you doing up there?”

Leo looked down. Beneath the window stood old Daniel Hawkins.

CHAPTER VII.—LEO GAINS HIS LIBERTY.

Daniel Hawkins had just come out to care for his horse. By sheer accident he had glanced up at the window and beheld Leo in the act of dropping out.

The young gymnast was as much surprised as was his tormentor. But he knew enough to cling fast to the sill, and not to drop into Daniel Hawkins’ clutches.

“Goin’ ter drop out, eh?” went on the old farmer.

“I rather think not,” replied Leo, and popped into the room again.

At once Daniel Hawkins called his wife.

“Marthy! Marthy!”

“Wot, Daniel?”

“Leo’s up in the house a-tryin’ ter climb out o’ the winder!”

“You don’t say!”

“Run up an’ catch him!”

“Why don’t you go?”

“I want ter watch out here fer him! If I go up he’ll drop anyway.”

“Drat the boy!” muttered Mrs. Hawkins, and she went for her old-time weapon, the broom.

Armed with this, she ascended the stairs. She entered the side bedroom, to which her husband had pointed, only to find it empty.

“He ain’t here!” she cried from the window.

“He’s somewhere? Root him out!” shouted Daniel Hawkins.

So Mrs. Hawkins ran around from room to room.

But she did not find Leo, for the simple reason that the young gymnast had, by running through two rooms, reached the stairs and gone down to the front door.

He opened this and ran outside just as Daniel Hawkins appeared around the corner of the porch, whip in hand.

“Stop, Leo!”

“Not to-day!” retorted the boy.

And away he went, Daniel Hawkins lumbering after him.

The farmer was no match for the young gymnast. Soon Leo was out of his sight, and he returned to the farmhouse to talk the matter over with his spouse.

“I’ll fix him yet, see ef I don’t!” he said to Martha.

Soon his bony nag was hitched up to a buckboard, and away went the farmer in pursuit of the lad, who was doing his best to get away.

“I’ll teach him a lesson he won’t forget in a hurry when I collar him,” thought the miserly man savagely.

On went the boy until nearly half the distance to Lendham, the next town, was covered. Wishing to throw the farmer off the scent, Leo did not head for the circus grounds.

As it was a hot day he was soon pretty well winded and he dropped into a walk.

On looking back he was chagrined to see the buckboard approaching.

“He means to catch me, after all!” he thought.

The young gymnast hardly knew what to do.

It was useless to think of going on, for his pursuer would sooner or later overtake him.

On both sides of the road were open fields, offering no place where he might conceal himself.

Suddenly an idea struck him.

He was approaching the inclosed grounds of the County Agricultural Society.

The county fair was in progress and thousands of people were in and about the inclosure.

Could he not lose himself in the crowd?

He resolved to make the attempt.

But he had not the price of admission, even though it was but twenty-five cents.

Yet this did not stop the youth.

“Necessity knows no law,” and just as Daniel Hawkins drove up within a hundred feet of him he ran in among the carriages at the gateway and entered the grounds before the gatekeeper could stop him.

“Hi, boy, stop! Where is your ticket?”

The policeman near the gatekeeper made a dash after Leo.

But the boy was not to be collared.

He sprang into the midst of a crowd, and that ended the chase so far as the guardian of the law went.

Leo did not remain near the gates, but following the crowd, he walked to one of the main buildings and then to the large field beyond.

Here was a small racecourse, and local horsemen were running races for small purses and side bets.

At once something in the center of the racetrack attracted Leo’s attention.

It was a very large balloon, swaying gracefully to and fro in the light breeze that was blowing.

The boy was interested on the instant, as he had not seen a balloon since he was a small boy.

“Father once went up in one of those things,” he mused, as he moved forward. “I would like to try it once myself.”

Around the balloon were half a dozen men, preparing for the ascension, to take place half an hour later.

Professor Williams, the aeronaut, had not yet put in appearance.

The balloon was about filled with hot air and the men were merely keeping the air warm until the professor should arrive.

As Leo stood by watching the arrangements an outsider came up.

“Too bad!” he said.

“What’s too bad?”

“The professor can’t get here to-day.”

“Why not?”

“He has been taken sick and is at the hotel in New Haven.”

“That will be a big disappointment to this crowd.”

“I admit it, but it can’t be helped.”

The boy listened to the conversation with interest.

He pushed his way to where the man in charge of the balloon stood.

“I’ll go up in the balloon for you, if you’ll pay me,” he said.

“You!” the man looked at him in astonishment.

“Yes.”

“It won’t do, my lad. The crowd want somebody who will make a parachute jump, and all that.”

“I’ll make the parachute jump if you’ll give me a few instructions.”

The man laughed.

“You’re a daring youngster, to say the least,” he remarked. “Why, you might break your neck.”

“No, I wouldn’t,” returned Leo confidently.

“Well, I’m much obliged, but I can’t use your services.”

“Let me get in the basket and see how it feels, will you?” asked the boy, after a pause.

“Well, seeing as you are so anxious, I’ll oblige you,” laughed the man.

The basket rested on the ground, directly to one side of the fire, with which the air in the swaying monster was kept hot.

Hardly had the man given permission than Leo entered the wicker inclosure.

It was about six feet in diameter and filled with bags of sand for ballast.

To one side of the basket was attached a parachute. This the balloonist used in making his daring jumps from the clouds.

As Leo sat in the basket the crowd gathered around him.

“Hullo, Leo Dunbar! what are you doing in that basket?” asked Ben Barkley, one of the rich boys of Hopsville.

“Going to make an ascension,” returned Leo jokingly.

“Bet you ten dollars you are not,” laughed Ben.

“All right; I’ll take you up. But you must loan me the money, Ben.”

“How is it old Hawkins gave you a day off?” went on Ben. “Thought he was too mean to give anybody a holiday.”

“So he is, Ben. I took a day off and I’m going to take more.”

“Phew! What do you mean? Have you and the old man parted company?”

“We have.”

“It is a wonder he would let you go—he got so much work out of you.”

“He didn’t let me go. I ran away.”

Ben Barkley’s eyes opened widely.

“You don’t mean it!”

“I do! I’m tired of being his slave.”

“I don’t blame you a bit for leaving,” was Ben’s decided reply. “I know what a hard-hearted man he is.”

“I’m going to carve my own way to fortune.”

“What are you going to do?”

Leo was about to answer when Ben was pushed to one side and the portly form of Daniel Hawkins appeared.

“Ha! ha! So I have found you at last, you scamp!” he cried in a rage. “A pretty run you have given me! And made me pay out twenty-five cents, too, to come in the fair after you!”

Leo was taken completely aback. He had not dreamed that the farmer would follow him into the grounds.

“I’ll skin you!” stormed the man, seeing the boy did not immediately answer him.

“Not much you won’t,” put in Ben Barkley.

“What have you to do with this?” howled Daniel, turning to the rich boy.

“You have no right to abuse Leo,” responded Ben.

“This is none of your business!”

“Hold him a minute, Ben!” suddenly shouted Leo. “Hold him!”

As the boy spoke he drew from his pocket a clasp-knife.

Quickly he opened the largest blade.

Slash! slash! slash!

He was cutting the ropes which held the balloon.

“Here! What are you doing!” screamed the man in charge.

“I’m going to escape a tyrant!” responded Leo, as he cut the last rope.

For an instant the balloon continued to sway from side to side.

Daniel Hawkins fought off Ben Barkley and leaped forward.

Too late!

Up shot the balloon, dragging the basket after it.

In less time than it takes to tell it, Leo Dunbar was five hundred feet up in the air!

CHAPTER VIII.—AMONG THE CLOUDS IN A THUNDERSTORM.

A cry arose.

“The balloon has gone up!”

“Why, the balloonist is nothing but a boy!”

“My! but ain’t it going up fast!”

Daniel Hawkins could do nothing but stare after the balloon.

“Foolish boy, he will be killed!” he gasped.

Ben Barkley was also amazed.

“He said he would go up,” he murmured, “but I never supposed that he meant it.”

The crowd continued to shout. They wondered what it all meant, and some asked the men who had had the balloon in charge, but those individuals had no time to explain.

They sprang into a wagon and prepared to follow the direction of the balloon, supposing it would come down as soon as the hot air began to cool off.

Meanwhile, what of Leo?

So sudden was the upward rush of the balloon that the boy was thrown to the bottom of the basket ere he was aware.

He clutched the sides and then ventured to look down. The earth seemed to be fading away beneath him.

For a few minutes he was deadly sick at the stomach and there was a strange ringing in his ears.

The balloon was moving in the direction of Hopsville. Soon it passed over the town.

Leo could see the few streets and the brook laid out like a map beneath him.

He was growing accustomed to his novel situation.

On and on went the balloon.

The wind appeared to blow stronger the higher he went.

Then he looked ahead and saw he was rushing rapidly toward a dense mass of clouds to the southeast.

The boy had noticed the clouds while running toward Lendham.

They betokened a thunderstorm, and already the mutterings of thunder came to his ears.

“A storm would be more than I bargained for,” he thought. “I wonder if I can’t get away from it?”

Leo had heard tell of going up above a storm when the latter hung low.

He did not know if he could make a hot-air balloon go up, but he resolved to try.

With great rapidity he threw out one sandbag after another.

Lightened of a great part of its load, the balloon shot up a hundred feet or more.

Then the boy noticed a large sponge tied to the side of the basket and beside a can labeled alcohol.

At once he saturated the sponge and placed it on the stick for that purpose.

When the sponge was lit he held it up to the mouth of the balloon.

The cooling air began to grow hot again, and once more the balloon went up slowly, but steadily.

But now the wind made the basket rock violently from side to side.

Soon Leo had to extinguish the sponge and put it away.

A gust sent the basket almost over to one side, and he had to let everything go in order to cling fast.

Sizz! A jagged streak of lightning crossed directly in front of the balloon!

He was now in the very midst of the storm and all grew black around him.

The change from the bright sunshine was terrible to the boy and he almost gave himself up for lost.

Back and forth rocked the balloon and the basket, and many were the times that he was in danger of being hurled to death.

Then the balloon began to descend.

The clouds were left behind, and there followed a deluge of rain which drenched Leo to the skin.

He fell so rapidly that a new danger presented itself.

Where or how would he land?

Would he break his neck or a limb?

Down, down he went! There were trees or bushes under him, he could not tell which.

Crash! The basket settled in the top of a tree.

Down came the folds of the balloon on top of it, and the boy was nearly smothered.

Yet he was exceedingly thankful that his life had been spared.

He crawled from the basket and carefully made his way down the tree to the ground.

The storm still raged, but gradually it moved onward, and the sun broke from beneath the scattering clouds.

Leo had traveled at least eight or ten miles, and he wondered what he should do next.

He had half a mind to run off and leave the balloon men to find their property as best they might.

But he soon changed his mind on that point.

“I’ll aid them all I can,” he said to himself.

The boy knew there was a road through the woods which ran almost directly to the fair grounds.

He made his way to this and walked on through the mud and wet.

It was not long before he came up to the men in the wagon.

At first they were inclined to be abusive, and they thought to have the boy locked up.

But Leo soon changed all this.

“Your balloon is all right,” he said. “And by going up I reckon I saved you the amount you were to get from the fair people. You wouldn’t get a cent if somebody hadn’t gone up.”

This was a new way of looking at it.

“Well, we won’t get paid for a parachute jump,” said the balloon manager. “But we can claim half money, true enough.”

The boy showed the men where the balloon was, and helped them load it on their wagon.

The men took to Leo, and as he helped them at the hardest work, they readily answered his questions about the circus and gave him full directions by which he could take a short cut to the grounds.

“That was a narrow escape,” murmured Leo to himself as he made his way back to the “Greatest Show on Earth.”

Arriving there, he had another long talk with Barton Reeve, who, as before stated, had taken a sudden and strong fancy to the brave lad.

The upshot of the matter was that Reeve bought Leo a trunk and advanced him money for several changes of clothing.

The next day, at Lendham, the circus tents were jammed with people.

Everything was again in order, and all the acts went off with a dash that drew round after round of applause.

Snipper was as sour as ever, but he took good care not to interfere with Leo.

As for the boy, he appeared perfectly at home; so much so that many said he was a born circus performer.

As a clown he caused the people to laugh heartily, and when he threw off his trunks and performed on the bars and rings he got more than a share of the applause.

As soon as the performance was over the circus packed up, and at half-past eleven began to move from Lendham to Middletown, seven miles distant.

Leo spent the night at the Middletown Hotel with Barton Reeve. The boy was now a protégé of the menagerie manager.

Before going to bed, Leo told Reeve much about his former life, and showed the manager the pictures of his folks.

Reeve became interested.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do, Leo,” he said. “I’ll go to this Squire Dobb and get him to release you in a lawful way. Then you will have nothing to fear from Daniel Hawkins.”

“But supposing Hawkins won’t let the squire release me?”

“I don’t believe he has any claim on you that would hold good in a court of law. I’ll make the squire show his authority over you first.”

“I wish you could get Squire Dobb to make a settlement of my parents’ estate,” went on Leo earnestly.

“You think he is holding money from you?”

“I know he is.”

“Well, I’ll investigate.”

Bright and early the next day the young lad and Barton Reeve drove over to the home of Nathan Dobb.

They found the squire busy in his office, looking over some legal papers.

Without preliminaries Barton Reeve introduced himself. The squire listened in silence, at the same time scowling at Leo.

“Want to quit the farm and become a circus performer, eh?” said Dobb at last. “Can’t let you do it. You’ll have to go back to Daniel Hawkins’ farm.”

“I never will!” returned Leo warmly. “I’ll run away entirely first.”

“We’ll see,” sniffed Squire Dobb.

Barton Reeve had sized up the lawyer at a glance. He saw that the man was a crafty villain, not to be trusted.

“Squire, would you mind showing me your authority over this boy?” he remarked firmly.

“Wh-what?” was the surprised exclamation.

“I would like to learn your legal authority over Leo.”

“It’s none of your business!”

“I shall make it my business.”

“Going to pry into matters, eh?”

“Yes, unless you consent to release Leo. He has been misused on the Hawkins’ place.”

The face of Nathan Dobb was a study. If there was one thing he feared it was the exposure of the past. Why he feared this will be explained later.

“I’ll have to see Hawkins first,” he said at last.

“When will you see him?”

“To-day. But what is Leo to do?”

“He is going to travel with me and perform in the circus.”

“He can’t do anything.”

“Never mind. I’ll teach him a thing or two,” replied Barton Reeve.

He was afraid if he told Squire Dobb what Leo could really do that the miserly lawyer would want money for the release.

After a little more talk Leo and Reeve left the squire’s house.

On the next day Reeve got a short note from Dobb. It read:

“I have given up all claim to Leo Dunbar, and so has Daniel Hawkins.”

Leo was much pleased. Barton Reeve smiled to himself.

“There is something in all this, Leo,” he said. “Next week, when I get time, I’ll look into your past and Squire Dobb’s doings.”

CHAPTER IX.—THE MAD ELEPHANT.

From Middletown the circus went to Dover, and then to Grasscannon.

At each of these places a big business was done, and at every performance Leo did better.

The young gymnast became a great favorite with all but two people in the “Greatest Show on Earth.”

These two people were Jack Snipper, who remained as overbearing as ever, and Jack Broxton, the fellow discharged for intoxication.

Broxton had been following up the circus ever since his discharge, in the vain hope of being reinstated.

But the rules in the “Greatest Show on Earth” are very strict, and no intoxication is allowed.

After leaving Grasscannon, the circus struck up through New York State, and at the end of the week arrived at Buffalo.

It was while at this place that Broxton tried to play a dangerous trick upon Leo.

He met the young gymnast on the street one night after the performance.

He was under the influence of liquor at the time, and in his pocket he carried what is known by the boys as a giant torpedo.

As Leo turned a corner he threw the torpedo at Leo’s feet.

Luckily the torpedo failed to explode.

Had it gone off the young gymnast would have been sadly crippled.

“You rascal!” cried Leo, and he made for Broxton and landed him in the gutter.

Some of the other performers then came up.

“What’s the row, Leo?”

“Look what Broxton threw at me,” he replied, and handed the torpedo around for inspection.

While the explosive was being examined, Broxton sneaked off, and it was well for him that he did so, for otherwise the crowd would have pounced upon him and given him the greatest warming up of his life.

But that ended Broxton’s hope of rejoining the circus. The story of his attempt on Leo circulated, and he did not dare to show his face anywhere around the dressing tents.

After leaving Buffalo the circus turned southward toward Pennsylvania.

One night they arrived at Harmony Falls.

“To-morrow, if all goes right, I am going to take a train for Hopsville and see Squire Dobb,” said Barton Reeve to Leo.

“I hope you have luck,” replied the boy. “If he is keeping any of my property back from me I want to know it.”

The day in Harmony Falls opened very warm. A haze hung over the mountains to the westward.

“We’ll have a storm by night,” said Natalie Sparks to Leo.

The two were now warm friends.

“That will make it bad for the ticket-wagon,” laughed the young gymnast.

“Oh, I hate a storm during a performance,” went on the girl, “especially if it thunders and lightens.”

“Well, that’s what it’s going to do.”

“How do you know?”

“Oh, didn’t I live on a farm?”

“That’s so!” Natalie laughed merrily. “You don’t look much like a farm hand now.”

“Thanks for the compliment,” and Leo blushed.

During the afternoon it grew hotter and hotter. Under the big tents it was suffocating.

“Dandy weather for lemonade,” said the owner of the main drinking stand, but he was about the only person who appreciated the sudden rise in the thermometer.

At seven o’clock the circus tents were again crowded, and amid the general excitement but few noticed the flashes of lightning over in the west. The low rumblings of thunder they attributed to the lions in the cages.

At last the grand entrée was over, and then the performance settled down to the various specialties.

Then, as Leo and Snipper came on, a louder peal of thunder attracted every one’s attention.

To quiet fears the band struck up. Of course Leo and Snipper could not talk against the music, and so they tumbled around instead, Leo casting himself into the most awkward of shapes.

The rain began to fall, but as the canvases were waterproof this did no great harm.

Then the wind freshened up, and every one realized that a big storm was at hand.

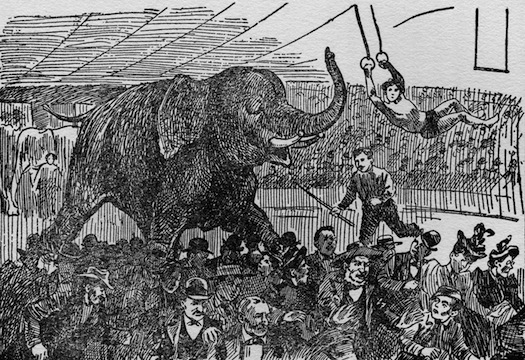

Leo had just thrown off his clown’s dress and mounted up to a pair of rings when a fearful crack of thunder caused every one to leap up in terror.

The lightning had struck a pole in the menagerie tent!

Down came the heavy stick, straight across the backs of three of the largest elephants.

The thunder and the fall of the pole frightened the huge beasts. They roared and plunged and finally broke from their fastenings.

Two of them were secured without much difficulty, but the third, the largest, could not be managed.

With a fearful roar he rushed into the main circus tent, under the spot where Leo was performing, and directly in the faces of the crowd, which tried in vain to flee from his path.

CHAPTER X.—CAPTURING THE ELEPHANT.

For the moment it looked as if the mad elephant would crush a dozen or more of the audience.

He was making straight for the crowd, which tried in vain to clear a path for him to pass.

The uproar was terrible, but it was nothing compared to the trumpeting of the gigantic beast.

Several attendants rushed toward the elephant with prods, but he was too angry to notice them.

“Turn him back!”

“He’ll walk right over the crowd!”

“Lasso him!”

“Shoot him!”

And so the cries went on.

The uproar had caused Leo to stop his performance; indeed, it had stopped everything but the stampede of the audience.

Suddenly the elephant ran directly under the young gymnast.

As he did so there came another crash of thunder.

The elephant raised up on his rear legs, and his trunk went up to where Leo swung.

And then a startling thing happened.

Leo dropped directly upon the beast’s head. With remarkable rapidity he slid back on to the neck.

“Throw me a rope!” he yelled to the nearest attendant, and the fellow did so.

Then the end of the elephant’s trunk came up angrily. He intended to catch hold of the young gymnast and hurl him to the earth, there to trample on him.

But Leo slipped further back, and at the same time threw the noose of the rope over the uplifted proboscis.

He hauled it taut, and with the end of the rope in his hand, sprang down and ran at lightning speed to the nearest centerpole.

Around this he went half a dozen times.

“Now keep him back with your prods!” he sang out.

More enraged than ever, the elephant tried to pull himself free.

But the rope held, and he was forced on his knees, roaring with pain, for an elephant’s trunk is his most sensitive organ.

A shout of approval went up, and the crowd paused in its hasty flight.

But the elephant was not yet a prisoner. He pulled and tugged, and had the centerpole not been so strong and so deeply set in the ground, he would surely have either broken it off or pulled it up.

But now he hesitated, and in that moment more attendants came up. One began to soothe him, while the others slipped a leather and iron harness over him. Soon he was a complete prisoner, and realizing this, he shambled back to the menagerie tent as mildly as a lamb.

The rain was now coming down in a perfect deluge, and the audience would not remain. In less than a quarter of an hour the circus grounds were deserted, saving for those who had to remain on duty, and the performers in the dressing-tents.

Every one praised Leo for what he had done; every one, that is, but Snipper. He had not a word to say, but looked more morose than ever.

Leo did not wait, however, to hear all that the others had to say. He donned his regular clothing just as quickly as he could, and with Natalie Sparks rode from the grounds to the hotel at which they were stopping.

Barton Reeve was nowhere around. He had gone off to Hopsville to see Nathan Dobb.

He came in about half-past ten, and then Leo and he had a long discussion concerning the boy’s past and future.

“The squire is a sly one,” said the menagerie manager. “It was about as easy to get information out of him as it is to get milk out of a stone.”

“Then you learned nothing?” returned Leo, much disappointed.

“I did and I didn’t. He admitted that your folks were once wealthy; but he said the money was lost in speculations before you were left an orphan.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“Nor I. I asked him for some proofs, but he would give me none. Then I asked him flatly how much there was coming to you when your folks died, and he said not more than a couple of hundred dollars. I wanted to see the papers, but he wouldn’t show them.”

“Didn’t you tell him we would take the matter to court?”

“I did, and it worried him a good bit. That is what makes me think there is considerable at stake. If he had nothing to hide, what is he so scared about?”

“Just wait till I have money enough, I’ll stir him up!” cried Leo.

He had not yet forgotten how Nathan Dobb and Daniel Hawkins had mistreated him.

“We’ll both stir him up, Leo. But I guess before we go much further we had better get a lawyer’s advice. In a few weeks the circus will make two three-day stops and that will give us a little time, certainly more than we get when we go to a new town every day.”

They talked the matter over for some time longer, and when Leo went to bed it was with the fixed determination to make Squire Dobb “toe the mark.”

And while the young gymnast was meditating thus, Nathan Dobb was walking up and down his office, his face dark and full of cunning.

“The boy’s getting too big and he’s making too many friends,” he muttered to himself. “Why couldn’t he remain a simple farm hand, without trying to rake up the past and make a place for himself?” He took a turn or two and clenched his bony hands. “I wish I had stuck to my original idea and sent him to Africa on that freight steamer without a cent in his pocket.”

Then Nathan Dobb dropped into the chair beside his safe, and from the strong box took a package of documents. These he looked over for nearly half an hour.

“Ten thousand dollars!” he muttered. “It would be a fortune to him! But he shan’t have it. I’ve worked too hard for it to have it slip through my fingers at this late day. I had better burn all these papers and then concoct some scheme for getting him out of the way.”

Nathan Dobb’s soliloquy was interrupted by a crash in the rear of the house. Some one had broken into the kitchen, most likely a burglar.

CHAPTER XI.—A CRIMINAL COMPACT.

There had been several robberies in Hopsville lately, so the squire was certain the burglar had now come to his house.

Instantly he turned out the light in the office. Then opening the door to the hall he listened attentively.

He was right; some one was moving cautiously about the kitchen.

Moving back to his desk the squire secured his pistol and also a club.

When he came out into the hall on tiptoe he heard the would-be burglar moving around the dining-room.

Presently the fellow struck a light, which he set on the table.

Then he began an examination of the silverware on the sideboard.

By the light the squire got a good look at the would-be burglar. He was astonished beyond measure.

“Hank Griswold!” he muttered, half-aloud.

The man whose name he mentioned had formerly been a tavern-keeper in Hopsville.

But he had been sent to jail for robbing and beating a drunken man. His discharge had taken place but two weeks before.

As Squire Dobb spoke, the would-be burglar turned swiftly.

“Collared!” he muttered laconically.

Then he tried to escape by a rear door, but Nathan Dobb covered him with the pistol.

“Stop, Griswold!”

“Confound the luck! The game is up!”

“It is. Stop where you are.”

“Don’t be hard on me, squire.”

“So you were going to rob me, eh?”

“Let me go this time, squire,” went on the man pleadingly.

“What for? So you can rob somebody else?”

“I ain’t got a cent to my name, squire.”

“I can’t help that.”

Suddenly a thought flashed over Squire Dobb’s mind.

“Griswold, step into my office.”

“Don’t lock me up, squire.”

“I won’t—if you will do as I wish you to.”

“I’ll do anything you say, only don’t arrest me again.”

“Step into the office, and see to it that you don’t wake up the whole household.”

Hank Griswold complied. The squire followed him, still, however, keeping his pistol ready for use.

But when the office was reached, and the door shut, Nathan Dobb’s manner changed. He took Griswold’s hand.

“Griswold, you are just the man I want to see.”

“I—I—don’t understand,” was the confused reply.

“I’ll explain. Sit down and take it easy. You love to smoke? Have a cigar,” and a box was shoved toward him.

“See here, Nathan Dobb, what’s your game now?”

“I want to throw some work in your hands, work that will pay well.”

“What kind of work?” asked Griswold suspiciously. He was half-inclined to believe Nathan Dobb was out of his mind.

“You just said you would do anything for me if I didn’t have you arrested.”

“So I will.” “Supposing I put a job in your way that will pay you an even hundred dollars——”

“You’re foolin’ me, squire.”

“I mean it, Griswold, a hundred dollars. Would you do the work and say nothing?”

“Yes.”

“It’s a—a—job that isn’t strictly—ah—all right, you know.”

“I don’t care what it is,” returned Griswold recklessly. “I’ll do anything you say. You can trust me.”

“Will you?” cried Nathan Dobb eagerly. He hesitated. “I want to get a boy out of my way.”

“Who?”

“Leo Dunbar, who used to live with Dan Hawkins.”

“I know him. Didn’t his father once have my tavern shut up as a disorderly house?”

“Well, as I said, I want to get that boy out of my way.”

“Where is he now?”

“He is traveling as an acrobat with that circus which performed here a week or so ago.”

“And you want me to—to—?” Griswold hesitated.

“I want him removed from my path. I never want to see him around here again.” “And you’ll give me a hundred for the job?”

“I will.”

“It’s not enough. Make it two hundred.”

“Well, I will.”

“In cash?”

“Yes.”

“When can I get the money?”

“You can get it right here as soon as—well, I’m sure Dunbar won’t bother me any more.”

“You’re a cool one, Dobb. But I said I’d go you, and I will. But, say?”

“Well?”

“You must let me have fifty dollars on account. I’ll have to hang around the circus for awhile and lay my plans. It’s no fool of a job to do as you wish.”

“Here are thirty dollars. And one word more, Hank. Never mention my name in this, and if I were you, don’t ever let Leo Dunbar see you.”

“I’ll remember,” replied Griswold.

Ten minutes later he left Nathan Dobb’s house as secretly as he had entered it.

CHAPTER XII.—THE STOLEN CIRCUS TICKETS.

ON the following week the circus moved down through Pennsylvania. Fine weather favored the show, and the crowd at each performance was very large.

“This is going to be a banner season,” said Giles, the treasurer, “unless we get tripped up as we were last season.”

He referred to a serious matter, namely, that of thousands of stolen tickets, which during the previous summer had been secured and sold by outside speculators.

This season a few tickets had thus far been missing, but the number was not sufficient to cause a serious loss.

Leo’s performances in the ring improved every day. Already was he as good as Jack Snipper, and soon he would outrival the other acrobat in every way.

Leo’s acts, while disguised as a clown, were highly amusing, even better than some of the regular clowns, of which there were eight.

“He could do clown and get big wages, even if he didn’t know a thing about gymnastics,” remarked Natalie Sparks.

Natalie was now a warm friend to Leo, much to Snipper’s disgust.

The second-rate gymnast had always been enamored of the Fire Queen, but he could make no progress in his suit.

One day he met Natalie in the dressing-tent when no one else was present.

He began to talk familiarly to her, and then attempted to kiss her.

“Don’t you dare!” she cried angrily.

“I guess you won’t mind very much,” said Snipper, and then, despite her struggles, he bent over and stuck his repulsive face close to her fair cheek.

But just then Leo came on the scene. For a moment he stood in amazement.

“Leo, make the horrid fellow go away!” panted Natalie.

“Do as Miss Sparks wishes, Snipper!” cried the young gymnast.

“Mind your own business!” grumbled Snipper.

“This is my business,” returned Leo warmly.

And rushing up, he collared the second-rate gymnast and hurled him halfway across the tent.

Snipper was clearly in the wrong, and, as Natalie had called on Leo for assistance, he did not dare raise a row.

He sneaked out, shaking his fist at Leo as he did so.

“Oh, Leo, I am very thankful you came in,” panted Natalie as soon as she could recover.

“So am I,” went on the boy honestly, and then, as he looked at the beautiful girl, both blushed.

Following the scene just recorded, Jack Snipper was more ugly than ever. Whenever he met or passed Leo he would mutter something under his breath.

“Look out for him, Leo,” said Dick Pomeroy, the tumbler, one day. “He’s cutting a club for you.”

“I’ve got my optics peeled,” laughed Leo.

That afternoon, after the performance, Leo was walking around outside, near the side-show.

Presently he saw something that at once interested him.

A “flim-flam worker,” as such criminals around a circus are called, was trying to swindle a countryman out of twenty dollars.

He was working an old game, which consists in getting an outsider to hold the stakes in a bet with another flim-flammer.

The game is to mix the stakeholder up and make him put up his own money, and then secure all the cash in sight.

Leo was interested for two reasons.

In the first place, he did not wish to see the countryman swindled.

In the second place, he knew that swindlers of any kind were not allowed to work in the vicinity of the “Greatest Show on Earth.”

The flim-flam man was about to receive the countryman’s money when Leo stepped up.

“Drop this,” he said quietly.

“Wot yer givin’ us, sonny?” came in a hoarse growl from the swindler.

“I say drop the game.” Leo turned to the countryman. “Put away your money, or you will be swindled out of it.”

“By gum! Is thet so?” ejaculated the farmer, and he at once thrust the cash out of sight.

At this the would-be swindler turned on Leo.

“I’ll thrash you for that!” he howled, and rushed at the young gymnast, while the two partners in the deal did the same.

Leo knew it would be foolish to attempt to stand up against all three, so he gave a peculiar whistle, known to all circus hands.

A cry of “Hi! Rube!” arose and soon several circus detectives reached the spot. But the swindlers vanished before they could be captured.

The countryman, whose name was Adam Slocum, was much pleased over what Leo had done, and insisted on shaking hands. He invited Leo to call on him when the circus came to the next town.

“Thank you, I’ll call,” said Leo.

Snipper had witnessed the scene between the swindlers and Leo. When the three men went off he followed them.

All four met at a low resort half a dozen blocks from the circus grounds.

Snipper knew the men. As a matter of fact, he would have left the circus and joined them in their work, but he had his reasons for remaining as an employee of the “Greatest Show on Earth,” as will be seen later.

The four men had a conference, which lasted over an hour.

Then Snipper and one of them called on a local locksmith.

The swindler told a long story of having lost the keys to his trunk, and he ordered the locksmith to make him three keys from impressions furnished by Snipper.

With these keys in his possession, Snipper went back to the circus grounds.

On the following day, toward evening, there was a commotion at the entrance to the main tent of the circus. One of the managers of the great aggregation had discovered that hundreds of circus tickets had been sold throughout the district at a discount from the regular price, fifty cents.

A hurried examination was made, and then it was learned that two thousand tickets had been stolen from one of the box-office wagons.

These tickets were now either sold to individuals or in the hands of the outside speculators.

Who could have stolen the tickets was a mystery, until a slip of paper was handed to Giles, the treasurer, which read:

“Leo Dunbar was hanging around the ticket wagon last night. Better watch and search him.

“A Friend.”

Giles lost no time in acting upon the suggestion given in the note. He ran to the dressing-tent and, finding a key to fit Leo’s trunk, opened it.