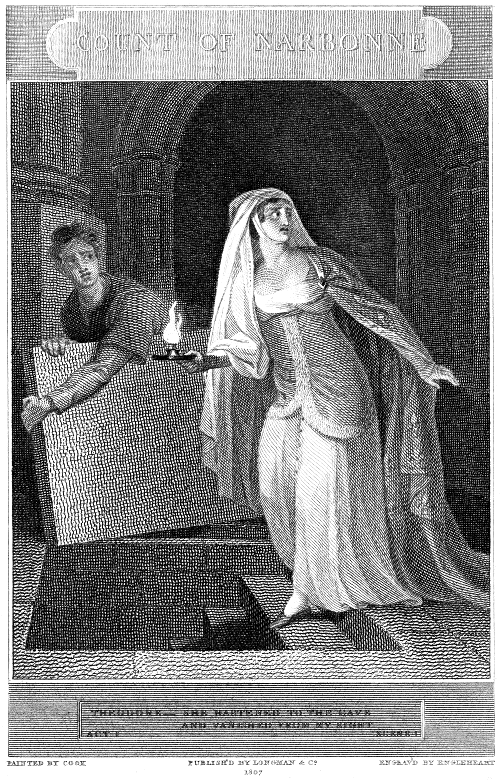

COUNT OF NARBONNE

THEODORE—SHE HASTENED TO THE CAVE AND VANISHED FROM MY SIGHT

ACT I SCENE I

PAINTED BY COOK PUBLISH'D BY LONGMAN & CO. ENGRAV'D BY ENGLEHEART

1807

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Count of Narbonne, by Robert Jephson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Count of Narbonne

A Tragedy, in Five Acts

Author: Robert Jephson

Commentator: Mrs. Inchbald

Release Date: July 1, 2011 [EBook #36575]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE COUNT OF NARBONNE ***

Produced by Steven desJardins, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

By ROBERT JEPHSON, Esq.

AS PERFORMED AT THE

THEATRE ROYAL, COVENT GARDEN.

PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MANAGERS

FROM THE PROMPT BOOK.

WITH REMARKS

BY Mrs. INCHBALD.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, AND ORME,

PATERNOSTER ROW.

WILLIAM SAVAGE, PRINTER

LONDON.

This tragedy was brought upon the stage in 1780; it was extremely admired, and exceedingly attractive.

Neither "The Winter's Tale", nor "Henry VIII" by Shakspeare, were at that time performed at either of the theatres; and the town had no immediate comparison to draw between the conjugal incidents in "The Count of Narbonne," and those which occur in these two very superior dramas.

The Cardinal Wolsey of Shakspeare, is, by Jephson, changed into a holy and virtuous priest; but his importance is, perhaps, somewhat diminished by a discovery, which was intended to heighten the interest of his character; but which is introduced in too sudden, and romantic a manner, to produce the desired consequence upon a well-judging auditor.

One of the greatest faults, by which a dramatist can disappoint and fret his auditor, is also to be met with in this play.—Infinite discourse is exchanged, numberless plans formed, and variety of passions agitated, concerning a person, who is never brought upon the stage—Such is the personal nonentity of Isabel, in this tragedy, and yet the fable could not proceed without her.—Alphonso, so much talked of, yet never seen, is an allowable absentee, having departed [pg 4] to another world; and yet, whether such invisible personages be described as alive, or dead, that play is the most interesting, which makes mention of no one character, but those which are introduced to the sight of the audience.

The lover of romances, whose happy memory, unclouded by more weighty recollections, has retained a wonderful story, by the late Lord Orford, called, "The Castle of Otranto," will here, it is said, find a resemblance of plot and incidents, the acknowledged effect of close imitation.

Lord Orford, (at that time Mr. Horace Walpole,) attended some rehearsals of this tragedy, upon the very account, that himself was the founder of the fabric.

The author was of no mean reputation in the literary world, for he had already produced several successful dramas. "The Count of Narbonne" proved to be his last, and his best composition.——Terror is here ably excited by descriptions of the preternatural—Horror, by the portraiture of guilt; and compassion, by the view of suffering innocence.—These are three passions, which, divided, might each constitute a tragedy; and all these powerful engines of the mind and heart, are here, most happily combined to produce that end,—and each forms a lesson of morality.

| Austin | Mr. Harley. |

| Theodore | Mr. Bloomfield. |

| Fabian | Mr. Thompson. |

| Officers | Mr. Powell. Mr. Evatt. |

| The Count | Mr. Farren. |

| Adelaide | Mrs. Merry. |

| Jaqueline | Mrs. Platt. |

| Countess | Mrs. Pope. |

| Officers, Attendants, &c. | |

SCENE.—Narbonne Castle, and the Monastery of St. Nicholas, adjoining to the Castle.

A Hall.

Enter the Count, speaking to an Officer; Fabian following.

Count. Not to be found! is this your faithful service?

How could she pass unseen? By hell, 'tis false!

Thou hast betray'd me.

Offi. Noble sir! my duty——

Count. Your fraud, your negligence—away, reply not.

Find her within this hour; else, by my life,

The gates of Narbonne shall be clos'd against thee;

Then make the world thy country.

[Exit Officer.

Fabian, stay!

Misfortunes fall so thick upon my head,

They will not give me time to think—to breathe.

Fab. Heaven knows, I wish your peace; but am to learn,

What grief more fresh than my young lord's decease,

A sorrow but of three days past, can move you.

Count. O bitter memory! gone, gone for ever!

The pillar of my house, my only son!

Fab. 'Twas terrible indeed.

Count. Ay, was it not?

And then the manner of it! think on that!

Disease, that robb'd me of two infant sons,

Approaching slow, bade me prepare to lose them;

I saw my lilies drooping; and, accustom'd

To see them dying, bore to see them dead:

But, Oh my Edmund!—Thou remember'st, Fabian,

How blithe he went to seek the forest's sport!

Fab. 'Would I could not remember!

Count. That cursed barb,

(My fatal gift) that dash'd him down the cliff,

Seem'd proud of his gay burden.—Breathless, mangled,

They bore him back to me. Fond man! I hoped

This day, this happy match with Isabel

Had made our line perpetual; and, this day,

The unfruitful grave receives him. Yes, 'tis fate!

That dreadful denunciation 'gainst my house,

No prudence can avert, nor prayers can soften.

Fab. Think not on that; some visionary's dream.

What house, what family could e'er know peace,

If such enthusiast's ravings were believ'd,

And phrensy deem'd an insight of the future?

But may I dare to ask, is it of moment

To stir your anger thus, that Isabel

Has left the castle?

Count. Of the deepest moment:

My best hope hangs on her; some future time,

I may instruct thee why.—These cares unhinge me:

Just now, a herald from her angry father

Left me this dire election—to resign

My titles, and this ample signory,

(Worthy a monarch's envy) or to meet him,

And try my right by arms. But pr'ythee tell,

(Nor let a fear to wound thy master's pride

Restrain thy licens'd speech) hast thou e'er heard

My father Raymond——(cast not down thine eye)

By any indirect or bloody means,

Procur'd that instrument, Alphonso's will,

That made him heir to Narbonne?

Fab. My best lord,

At all times would I fain withhold from you,

Intelligence unwelcome, but most now.

At seasons such as this, a friendly tongue

Should utter words like balm; but what you ask—

Count. I ask, to be inform'd of. Hast thou known me

From childhood, up to man, and canst thou fear

I am so weak of soul, like a thin reed,

To bend and stagger at such puny blast?

No; when the tempest rages round my head,

I give my branches wider to the air,

And strike my root more deeply.—To thy tale:

Away with palliatives and compliments;—

Speak plainly.

Fab. Plainly, then, my lord, I have heard

What, for the little breath, I have to draw,

I would not, to the black extent of rumour,

Give credit to.—But you command me speak—

Count. Thy pauses torture me.—Can I hear worse

Than this black scroll contains? this challenge here,

From Isabella's father, haughty Godfrey?

In broad, and unambiguous words, he tells me,

My father was a murderer, and forg'd

Alphonso's testament.

Fab. From Palestine,

That tale crept hither; where, foul slander says,

The good Alphonso, not, as we believe,

Died of a fever, but a venom'd draught,

Your father, his companion of the cross,

Did with his own hand mingle; his hand too,

Assisted by some cunning practisers,

Model'd that deed, which, barring Godfrey's right,

And other claims from kindred, nam'd Count Raymond

Lord of these fair possessions.

Count. Ha! I have it;

'Tis Godfrey's calumny; he has coin'd this lie;

And his late visit to the Holy Land,

No doubt, has furnish'd likelihood of proof,

To give his fiction colour.

Fab. Sure, 'tis so.

Count. He, too, has forg'd this idle prophecy,

(To shake me with false terrors) this prediction,

Which, but to think of, us'd to freeze my veins;

"That no descendant from my father's loins,

Should live to see a grandson; nor Heaven's wrath

Cease to afflict us, till Alphonso's heir

Succeeded to his just inheritance."

Hence superstition mines my tottering state,

Loosens my vassals' faith, and turns their tears,

Which else would fall for my calamities,

To gloomy pause, and gaping reverence:

While all my woes, to their perverted sense,

Seem but the marvellous accomplishment

Of revelation, out of nature's course.

Fab. Reason must so interpret. Good my lord,

What answer was return'd to Godfrey's challenge?

Count. Defiance.

Fab. Heaven defend you!

Count. Heaven defend me!

I hope it will, and this right arm to boot.

But, hark! I hear a noise.—Perhaps my people

Have found the fugitive.—Haste! bid them enter.

[Exit Fabian.

Enter Officer.

Now, what tidings?

Where is the lady?

Offi. We have search'd in vain

The castle round; left not an aisle, or vault,

Unvisited.

Count. Damnation!

Offi. Near the cloister,

From whence, by the flat door's descent, a passage

Beneath the ground leads onward to the convent,

We heard the echo of a falling weight,

And sought it by the sound.

Count. Well, and what then?

Offi. The unsettled dust left us no room to doubt

The door had just been rais'd.

Count. She has escap'd,

And by confed'racy: to force that bar,

Without more aid, had baffled twice her strength.

Go on.

Offi. We enter'd; with resistance bold.

Theodore brought in by Fabian and Attendants.

This peasant push'd us backward from the spot.

My arm was rais'd to smite him, but respect

For something in his aspect, check'd the blow.

He, chiding, parleying by turns, gave time

For whosoever had descended there

(The lady doubtless) to elude our search:

The rest, himself will tell.

Count. [To Theodore.] Ha! what art thou?

Theodore. It seems, thy prisoner: disengage me first

From their rude grasp, and I may tell thee more.

Count. Unhand him. I should know thee; I have seen

Features like thine. Answer me, wert thou found

As these men say?

Theod. I was.

Count. And what thy purpose?

Theod. Chance brought me there.

Count. And did chance lead thee, too,

To aid a fugitive?

Theod. They saw not that.

Count. They saw it not! How! could her delicate hands,

Weak, soft, and yielding to the gentlest touch,

Sustain that pond'rous mass? No; those tough arms,

Thy force, assisted; else, thou young dissembler——

Theod. She had been seiz'd, and by compulsion brought

Where I stand now.

Count. Thou dost avow it then,

Boast it even to my face, audacious stripling!

Such insolence, and these coarse rustic weeds

Are contradictions. Answer me, who art thou?

Theod. Less than I should be; more than what I seem.

Count. Hence with this saucy ambiguity.

What is thy name, thy country? That mean habit,

Which should teach humbleness, speaks thy condition.

Theod. My name is Theodore, my country, France,

My habit little suited to my mind,

Less to my birth, yet fit for my condition.

Count. O, thou art then, some young adventurer,

Some roving knight, a hero in disguise,

Who, scorning forms of vulgar ceremony,

No leave obtain'd, waiting no invitation,

Enters our castles, wanders o'er our halls,

To succour dames distress'd, or pilfer gold.

Theod. There is a source of reverence for thee here,

Forbids me, though provok'd, retort thy taunts.

Count. If I endure this more, I shall grow vile

Even to my hinds——

Theod. Hold, let me stop thy wrath.

I see thy quivering lip, thy fiery eye,

Forerun a storm of passion. To prevent thee

From terms too harsh, perhaps, for thee to offer,

Or me to hear (poor as I seem) with honour,

I will cut short thy interrogatories,

And on this theme give thee the full extent

Of all I know, or thou canst wish to learn.

Count. Do it.

Theod. Without a view to thwart thy purpose.

(Be what it might), was I within thy walls.

In a dim passage of the castle-aisles,

Musing alone, I heard a hasty tread,

And breath drawn short, like one in fear of peril.

A lady enter'd, fair she seem'd, and young,

Guiding her timorous footsteps by a lamp;

"The lord, the tyrant of this place, (she cried)

For a detested purpose, follows me;

Aid me, good youth:" then pointing to the ground,

"That door," she added, "leads to sanctuary."

I seiz'd an iron hold, and, while I tugg'd

To heave the unwilling weight, I learn'd her title.

Count. The Lady Isabel?

Theod. The same. A gleam,

Shot from their torches, who pursued her track,

Prevented more; she hasten'd to the cave,

And vanish'd from my sight.

Count. And did no awe,

No fear of him, she call'd this castle's lord,

Its tyrant, chill thee?

Theod. Awe, nor fear, I know not,

And trust, shall never; for I know not guilt.

Count. Then thou, it seems, art master here, not I;

Thou canst control my projects, blast my schemes,

And turn to empty air my power in Narbonne.

Nay, should my daughter chuse to fly my castle,

Against my bidding, guards and bolts were vain:

This frize-clad champion, gallant Theodore,

Would lend his ready arm, and mock my caution.

Theod. Thy daughter! O, I were, indeed, too bless'd,

Could I but live to render her a service!

Count. My daughter, would, I hope, disdain thy service.

Theod. Wherefore am I to blame? What I have done,

Were it to do again, again I'd do it.

And may this arm drop palsied by my side,

When its cold sinews shrink to aid affliction!

Count. Indeed!

Theod. Indeed. Frown on.—Ask thy own heart,—

Did innocence and beauty bend before thee,

Hunted, and trembling, wouldst thou tamely pause,

Scanning pale counsel from deliberate fear,

And weigh each possibility of danger?

No; the instinctive nobleness of blood

Would start beyond the reach of such cold scruples,

And instant gratify its generous ardour.

Count. [Aside.] I must know more of this. His phrase, his look,

His steady countenance, raise something here,

Bids me beware of him.—I have no time

To bandy idle words, with slaves like thee.

I doubt not thy intent was mischievous;

Booty perhaps, or blood. Till more inquiry

Clear, or condemn him, hold him in your guard.

Give none admittance—Take him from my sight.

Theod. Secure in her integrity, my soul

Casts back thy mean suspicions, and forgives thee.

[Theodore is led out by Attendants.

Count. Away with him!—What means this heaviness?

My heart, that, like a well trimm'd, gallant bark,

Was wont to mount the waves, and dash them off

In ineffectual foam, now seems to crack,

And let in each assailing tide to sink me.

I must not yield to this dull lethargy.

Good Fabian, hie thee to Saint Nicholas';

Bid holy Austin straight repair to me.

[Exit Fabian.

His sanctity, and reverend character,

His pious eloquence, made engines for me,

Might save a world of anguish to my soul,

And smooth my unwelcome purpose to Hortensia.

But how prevail with him?—Ambition?—No;

The world is dead in him, and gold is trash

To one, who neither needs, nor values it.

Interest and love shall wear the guise of conscience;

I must pretend nice scruples, which I feel not,

And make him mediate for me with the church.

Yet he reveres the countess; and, I fear,

Will spy more sin, in doubts that wound her quiet,

Than in my stifling them. But see, she comes,

With downcast eye, and sad, dejected mien.

I will not yet disclose it.

Enter the Countess.

Where's my child,

My all of comfort, now, my Adelaide?

Countess. Dear as she is, I would not have her all;

For I should then be nothing. Time has been,

When, after three long days of absence from you,

You would have question'd me a thousand times,

And bid me tell each trifle of myself;

Then, satisfied at last, that all were well,

At last, unwilling, turn to meaner cares.

Count. This is the nature, still of womankind;

If fondness be their mood, we must cast off

All grave-complexion'd thought, and turn our souls

Quite from their tenour, to wild levity;

Vary with all their humours, take their hues,

As unsubstantial Iris from the sun:

Our bosoms are their passive instruments;

Vibrate their strain, or all our notes are discord.

Countess. Oh, why this new unkindness? From thy lips

Never till now fell such ungentle words,

Nor ever less was I prepar'd to meet them.

Count. Never till now was I so urg'd, beset,

Hemm'd round with perils.

Countess. Ay, but not by me.

Count. By thee, and all the world. But yesterday,

With uncontrollable and absolute sway

I rul'd this province, was the unquestion'd lord

Of this strong castle, and its wide domains,

Stretch'd beyond sight around me; and but now,

The axe, perhaps, is sharp'ning, may hew down

My perish'd trunk, and give the soil I sprung from,

To cherish my proud kinsman Godfrey's roots.

Countess. Heaven guard thy life! His dreadful summons reach'd me.

This urg'd me hither. On my knees I beg,

(And I have mighty reasons for my prayer)

O do not meet him on this argument:

By gentler means strive to divert his claim;

Fly this detested place, this house of horror,

And leave its gloomy grandeur to your kinsman.

Count. Rise, fearful woman! What! renounce my birthright?

Go forth, like a poor, friendless, banish'd man,

To gnaw my heart in cold obscurity!

Thou weak adviser! Should I take thy counsel,

Thy tongue would first upbraid—thy spirit scorn me.

Countess. No, on my soul!—Is Narbonne all the world?

My country is where thou art; place is little:

The sun will shine, the earth produce its fruits,

Cheerful, and plenteously, where'er we wander.

In humbler walks, bless'd with my child and thee.

I'd think it Eden in some lonely vale,

Nor heave one sigh for these proud battlements.

Count. Such flowery softness suits not matron lips.

But thou hast mighty reasons for thy prayer:

They should be mighty reasons, to persuade

Their rightful lord to leave his large possessions,

A soldier challeng'd, to decline the combat.

Countess. And are not prodigies, then, mighty reasons?

The owl mistakes his season, in broad day

Screaming his hideous omens; spectres glide,

Gibbering and pointing as we pass along;

While the deep earth's unorganized caves

Send forth wild sounds, and clamours, terrible;

These towers shake round us, though the untroubled air

Stagnates to lethargy:—our children perish,

And new disasters blacken every hour.

Blood shed unrighteously, blood unappeas'd,

(Though we are guiltless,) cries, I fear, for vengeance.

Count. Blood shed unrighteously! have I shed blood?

No; nature's common frailties set aside,

I'll meet my audit boldly.

Countess. Mighty Lord!

O! not on us, with justice too severe,

Visit the sin, not ours.

Count. What can this mean?

Something thou wouldst reveal, that's terrible.

Countess. Too long, alas! it has weigh'd upon my heart;

A thousand times I have thought to tell thee all;

But my tongue falter'd, and refus'd to wound thee.

Count. Distract me not, but speak.

Countess. I must. Your father

Was wise, brave, politic; but mad ambition,

(Heaven pardon him!) it prompts to desperate deeds.

Count. I scarce can breathe. Pr'ythee be quick, and ease me.

Countess. Your absence on the Italian embassy

Left him, you know, alone to my fond care.

Long had some hidden grief, like a slow fire,

Wasted his vitals;—on the bed of death,

One object seem'd to harrow up his soul,

The picture of Alphonso in the chamber:

On that, his eye was set.—Methinks I see him,

His ashy hue, his grisled, bristling hair,

His palms spread wide. For, ever would he cry,

"That awful form—how terrible he frowns!

See, how he bares his livid, leprous breast,

And points the deadly chalice!"

Count. Ha! even so!

Countess. Sometimes he'd seize my hands, and grasp them close,

And strain them to his hollow, burning eyes;

Then falter out, "I am, I am a villain!

Mild angel, pray for me;—stir not, my child;

It comes again;—oh, do not leave my side."

At last, quite spent with mortal agonies,

His soul went forth—and Heaven have mercy on him!

Count. Enough! Thy tale has almost iced my blood.

Let me not think. Hortensia, on thy duty,

Suffer no breath like this to pass thy lips:

I will not taint my noble father's honour,

By vile suspicions, suck'd from nature's dregs,

And the loose, ravings of distemper'd fancy.

Countess. Yet, Oh, decline this challenge!

Count. That, hereafter.

Mean time, prepare my daughter to receive

A husband of my choice. Should Godfrey come,

(Strife might be so prevented) bid her try

Her beauty's power. Stand thou but neuter, Fate!

Courage, and art, shall arm me from mankind.

[Exeunt.

A Chamber.

Enter Fabian and Jaqueline.

Fab. No, no, it cannot be. My lord's commands

Were absolute, that none should visit him.

Jaq. What need he know it?

Fab. But perchance he should?

The study of my life has been his pleasure;

Nor will I risk his favour, to indulge

Such unavailing curiosity.

Jaq. Call it not so; I have kind counsel for him;

Which, if he follow it, may serve to speed

The hour of his deliverance, and appease

The unjustly-anger'd count.

Fab. Pray be content;

I dare not do it. Have this castle's walls

Hous'd thee nine years, and, art thou yet to learn

The temper of the count? Serv'd and obey'd,

There lives not one more gracious, liberal;

Offend him, and his rage is terrible;

I'd rather play with serpents. But, fair Jaqueline,

Setting aside the comeliness and grace

Of this young rustic, which, I own, are rare,

And baits to catch all women, pr'ythee tell,

Why are you thus solicitous to see him?

Jaq. In me, 'twere base to be indifferent:

He was my life's preserver, nay, preserv'd

A life more precious: yes, my dear young mistress!

But for his aid, the eternal sleep of death

Had clos'd the sweetest eyes that ever beam'd.

Aloof, and frighted, stood her coward train,

And saw a furious band of desperate slaves,

Inur'd to blood and rapine, bear her off.

Fab. What! when the gang of outlaw'd Thiery

Rush'd on her chariot, near the wood of Zart,

Was he the unknown youth, who succour'd her

All good betide him for it.

Jaq. Yes, 'twas he.

From one tame wretch he snatch'd a half-drawn sword,

And dealt swift vengeance on the ruffian crew.

Two, at his feet stretch'd dead, the rest, amaz'd,

Fled, muttering curses, while he bore her back,

Unhurt, but by her fears.

Fab. He should be worshipp'd,

Have statues rais'd to him; for, by my life,

I think, there does not breathe another like her.

It makes me young, to see her lovely eyes:

Such charity! such sweet benevolence!

So fair, and yet so humble! prais'd for ever,

Nay, wonder'd at, for nature's rarest gifts,

Yet lowlier than the lowest.

Jaq. Is it strange,

Fair Adelaide and I, thus bound to him,

Are anxious for his safety? What offence

(And sure, 'twas unintended) could provoke

The rigorous count thus to imprison him?

Fab. My lord was ever proud and choleric;

The youth, perhaps unus'd to menaces,

Brook'd them but ill, and darted frown for frown:

This stirr'd the count to fury. But fear nothing;

All will be well; I'll wait the meetest season,

And be his advocate.

Fab. Assure her, that the man, who sav'd her life,

Is dear to Fabian as his vital blood.

[Exit.

Enter Adelaide.

Adel. I sent thee to his prison. Quickly tell me,

What says he, does he know my sorrow for him?

Does he confound me with the unfeeling crew,

Who act my father's bidding? Can his love

Pity my grief, and bear this wrong with patience?

Jaq. I strove in vain to enter. Fabian holds him,

By the count's charge, in strictest custody;

And, fearful to awake his master's wrath,

Though much unwilling, bars me from his presence.

Adel. Unkind old man! I would myself entreat him,

But fear my earnest look, these starting tears,

Might to the experience of his prying age

Reveal a secret, which, in vain, I strive

To hide from my own breast.

Jaq. Alas, dear lady,

Did not your tongue reveal it, your chang'd mien,

Once lighter than the airy wood-nymph's shade,

Now turn'd to pensive thought and melancholy,—

Involuntary sighs,—your cheek, unlike

Its wonted bloom, as is the red-vein'd rose,

To the dim sweetness of the violet—

These had too soon betray'd you. But take heed;

The colour of our fate too oft is ting'd,

Mournful, or bright, but from our first affections.

Adel. Foul disproportion draws down shame on love,

But where's the crime in fair equality?

Mean birth presumes a mind uncultivate,

Left to the coarseness of its native soil,

To grow like weeds, and die, like them, neglected;

But he was born my equal; lineag'd high,

And titled as our great ones.

Jaq. How easy is our faith to what we wish!

His story may be feign'd.

Adel. I'll not mistrust him.

Since the bless'd hour, that brought him first to save me,

How often have I listen'd to the tale!

Gallant, generous youth!

Thy sport, misfortune, from his infant years!—

Wilt thou pursue him still?

Jaq. Indeed, 'tis hard.

Adel. But, oh, the pang, that these ungrateful walls

Should be his prison! Here, if I were aught,

His presence should have made it festival;

These gates, untouch'd, had leap'd to give him entrance,

And songs of joy made glad the way before him.

Instead of this, think what has been his welcome!

Dragg'd by rude hands before a furious judge,

Insulted, menac'd, like the vilest slave,

And doom'd, unheard, to ignominious bondage.

Jaq. Your father knew not of his service to you?

Adel. No, his indignant soul disdain'd to tell it.

Great spirits, conscious of their inborn worth,

Scorn by demand, to force the praise they merit;

They feel a flame beyond their brightest deeds,

And leave the weak to note them, and to wonder.

Jaq. Suppress these strong emotions. The count's eye

Is quick to find offence. Should he suspect

This unpermitted passion, 'twould draw down

More speedy vengeance on the helpless youth,

Turning your fatal fondness to his ruin.

Adel. Indeed, I want thy counsel. Yet, oh, leave me!

Find, if my gold, my gems, can ransom him.

Had I the world, it should be his as freely.

Jaq. Trust to my care. The countess comes to seek you;

Her eye is this way bent. Conceal this grief;

All may be lost, if you betray such weakness.

[Exit.

Adel. O love! thy sway makes me unnatural.

The tears, which should bedew the grave, yet green,

Of a dear brother, turning from their source,

Forget his death, and fall for Theodore.

Enter the Countess.

Countess. Come near, my love! When thou art from my side,

Methinks I wander like some gloomy ghost,

Who, doom'd to tread alone a dreary round,

Remembers the lost things, that made life precious,

Yet sees no end of cheerless solitude.

Adel. We have known too much of sorrow; yet, 'twere wise

To turn our thoughts from what mischance has ravish'd,

And rest on what it leaves. My father's love——

Countess. Was mine, but is no more. 'Tis past, 'tis gone.

That ray, at last, I hoped would never set,

My guide, my light, through, fortune's blackest shades:

It was my dear reserve, my secret treasure;

I stor'd it up, as misers hoard their gold,

Sure counterpoise for life's severest ills:

Vain was my hope; for love's soft sympathy,

He pays me back harsh words, unkind, reproof,

And looks that stab with coldness.

Adel. Oh, most cruel!

And, were he not my father, I could rail;

Call him unworthy of thy wondrous virtues;

Blind, and unthankful, for the greatest blessing

Heaven's ever-bounteous hand could shower upon him.

Countess. No, Adelaide; we must subdue such thoughts:

Obedience is thy duty, patience mine.

Just now, with stern and peremptory briefness,

He bade me seek my daughter, and dispose her

To wed, by his direction.

Adel. The saints forbid!

To wed by his direction! Wed with whom?

Countess. I know not whom. He counsels with himself.

Adel. I hope he cannot mean it.

Countess. 'Twas his order.

Adel. O madam! on my knees——

Countess. What would my child?

Why are thy hands thus rais'd? Why stream thine eyes?

Why flutters thus thy bosom? Adelaide,

Speak to me! tell me, wherefore art thou thus?

Adel. Surprise and grief—I cannot, cannot speak.

Countess. If 'tis a pain to speak, I would not urge thee.

But can my Adelaide fear aught from me?

Am I so harsh?

Adel. Oh no! the kindest, best!

But, would you save me from the stroke of death,

If you would not behold your daughter, stretch'd,

A poor pale corse, and breathless at your feet,

Oh, step between me and this cruel mandate!

Countess. But this is strange!—I hear your father's step:

He must not see you thus: retire this moment.

I'll come to you anon.

Adel. Yet, ere I go,

O make the interest of my heart your own;

Nor, like a senseless, undiscerning thing,

Incapable of choice, nor worth the question,

Suffer this hasty transfer of your child:

Plead for me strongly, kneel, pray, weep for me;

And angels lend your tongue the power to move him!

[Exit.

Countess. What can this mean, this ecstacy of passion!

Can such reluctance, such emotions, spring

From the mere nicety of maiden fear?

The source is in her heart; I dread to trace it,

Must then a parent's mild authority

Be turn'd a cruel engine, to inflict

Wounds on the gentle bosom of my child?

And am I doom'd to register each day

But by some new distraction?—Edmund! Edmund!

In apprehending worse even than thy loss,

My sense, confused, rests on no single grief;

For that were ease to this eternal pulse,

Which, throbbing here, says, blacker fates must follow;

Enter Count and Austin, meeting.

Count. Welcome, thrice welcome! By our holy mother,

My house seems hallow'd, when thou enter'st it.

Tranquillity and peace dwell ever round thee;

That robe of innocent white is thy soul's emblem,

Made visible in unstain'd purity.

Once more thy hand.

Aust. My daily task has been,

So to subdue the frailties we inherit,

That my fair estimation might go forth,

Nothing for pride, but to an end more righteous:

For, not the solemn trappings of our state,

Tiaras, mitres, nor the pontiff's robe,

Can give such grave authority to priesthood,

As one good deed of grace and charity.

Count. We deem none worthier. But to thy errand!

Aust. I come commission'd from fair Isabel.

Count. To me, or to the Countess?

Countess. Alas! where is she?

Till now I scarce had power to think of her;

But 'tis the mournful privilege of grief,

To stand excus'd from kind observances,

Which else, neglected, might be deem'd offence.

Aust. She dwells in sanctuary at Saint Nicholas':

Why she took refuge there——

Count. Retire, Hortensia.

I would have private conference with Austin,

No second ear must witness.

Countess. May I not,

By this good man, solict her return?

Count. Another time; it suits not now.—Retire.

[Exit Countess.

You come commission'd from fair Isabel?

Aust. I come commission'd from a greater power,

The Judge of thee, and Isabel, and all.

The offer of your hand in marriage to her,

With your propos'd divorce from that good lady,

That honour'd, injur'd lady, you sent hence,

She has disclos'd to me.

Count. Which you approve not:

So speaks the frowning prelude of your brow.

Aust. Approve not! Did I not protest against it,

With the bold fervour of enkindled zeal,

I were the pander of a love, like incest;

Betrayer of my trust, my function's shame,

And thy eternal soul's worst enemy.

Count. Yet let not zeal, good man, devour thy reason.

Hear first, and then determine. Well you know,

My hope of heirs has perish'd with my son;

Since now full seventeen years, the unfruitful curse

Has fallen upon Hortensia. Are these signs,

(Tremendous signs, that startle Nature's order!)

Graves casting up their sleepers, earth convuls'd,

Meteors that glare my children's timeless deaths,

Obscure to thee alone?—I have found the cause.

There is no crime our holy church abhors,

Not one high Heaven more strongly interdicts,

Than that commixture, by the marriage rite,

Of blood too near, as mine is to Hortensia.

Aust. Too near of blood! oh, specious mockery!

Where have these doubts been buried twenty years?

Why wake they now? And am I closetted

To sanction them? Take back your hasty words,

That call'd me wise or virtuous; while you offer

Such shallow fictions to insult my sense,

And strive to win me to a villain's office.

Count. The virtue of our churchmen, like our wives,

Should be obedient meekness. Proud resistance,

Bandying high looks, a port erect and bold,

Are from the canon of your order, priest.

Learn this, for here will I be teacher, Austin;

Our temporal blood must not be stirr'd thus rudely:

A front that taunts, a scanning, scornful brow,

Are silent menaces, and blows unstruck.

Aust. Not so, my lord; mine is no priestly pride:

When I put off the habit of the world,

I had lost all that made it dear to me,

And shook off, to my best, its heat and passions.

But can I hold in horror this ill deed,

And dress my brow in false approving smiles?

No: could I carry lightning in my eye,

Or roll a voice like thunder in your ears,

So should I suit my utterance to my thoughts,

And act as fits my sacred ministry.

Count. O father! did you know the conflict here;

How love and conscience are at war within me;

Most sure, you would not treat my grief thus harshly.

I call the saints to witness, were I master,

To wive the perfect model of my wish,

For virtue, and all female loveliness,

I would not rove to an ideal form,

But beg of Heaven another like Hortensia.——

Yet we must part.

Aust. And think you to excuse

A meditated wrong to excellence,

By giving it acknowledgment and praise?

Rather pretend insensibility;

Feign that thou dost not see like other men;

So may abhorrence be exchang'd for wonder,

Or men from cursing fall to pity thee.

Count. You strive in vain; no power on earth can shake me.

I grant my present purpose seems severe,

Yet are there means to smooth severity,

Which you, and only you, can best apply.

Aust. Oh no! the means hang there, there by your side:

Enwring your fingers in her flowing hair,

And with that weapon drink her heart's best blood;

So shall you kill her, but not cruelly,

Compar'd to this deliberate, lingering murder.

Count. Away with this perverseness! Get thee to her;

Tell her my heart is hers; here deep engrav'd

In characters indelible, shall rest

The sense of her perfections. Why I leave her,

Is not from cloy'd or fickle appetite

(For infinite is still her power to charm;)——

But Heaven will have it so.

Aust. Oh, name not Heaven!

'Tis too profane abuse.

Count. Win her consent.

(I know thy sway is boundless o'er her will,)

Then join my hand to blooming Isabel.

Thus, will you do to all most worthy service;

The curse, averted thus, shall pass from Narbonne;

My house again may flourish; and proud Godfrey,

Who now disputes, will ratify my title,

Pleas'd with the rich succession to his heirs.

Aust. Has passion drown'd all sense, all memory?

She was affianc'd to your son, young Edmund.

Count. She never lov'd my son. Our importunity

Won her consent, but not her heart, to Edmund.

Aust. Did not that speak her soul pre-occupied?

Some undivulg'd and deep-felt preference?

Count. Ha! thou hast rous'd a thought: This Theodore!

(Dull that I was, not to perceive it sooner!)

He is her paramour! by Heaven, she loves him!

Her coldness to my son; her few tears for him;

Her flight; this peasant's aiding her; all, all,

Make it unquestionable;—but he dies.

Aust. Astonishment! What does thy phrensy mean?

Count. I thank thee, priest! thou serv'st me 'gainst thy will.

That slave is in my power. Come, follow me.

Thou shalt behold the minion's heart torn out;

Then to his mistress bear the trembling present.

[Exeunt.

A Hall.

Enter Adelaide, Jaqueline following.

Jaq. Where do you fly? Heavens! have you lost all sense?

Adel. Oh, 'would I had! for then I should not feel;

But I have sense enough to know I am wretched,

To see the full extent of misery,

Yet not enough to teach me how to bear it.

Jaq. I did not think your gentleness of nature

Could rise to such extremes.

Adel. Am I not tame?

What are these tears, this wild, dishevel'd hair?

Are these fit signs for such despair as mine?

Women will weep for trifles, bawbles, nothing.

For very frowardness will weep as I do:

A spirit rightly touch'd would pierce the air,

Call down invisible legions to his aid,

Kindle the elements.—But all is calm;

No thunder rolls, no warning voice is heard,

To tell my frantic father, this black deed

Will sink him down to infinite perdition.

Jaq. Rest satisfied he cannot be so cruel

(Rash as he is) to shed the innocent blood

Of a defenceless, unoffending youth.

Adel. He cannot be so cruel? Earth and heaven!

Did I not see the dreadful preparations?

The slaves, who tremble at my father's nod,

Pale, and confounded, dress the fatal block?

But I will fly; fall prostrate at his feet;

If nature is not quite extinguish'd in him,

My prayers, my tears, my anguish, sure will move him.

Jaq. Move him indeed! but to redoubled fury:

He dooms him dead, for loving Isabel;

Think, will it quench the fever of his rage,

To find he durst aspire to charm his daughter.

Adel. Did I hear right? for loving Isabel?

I knew not that before. Does he then love her?

Jaq. Nothing I heard distinctly; wild confusion

Runs through the castle: every busy fool,

All ignorant alike, tells different tales.

Adel. Away, it cannot be. I know his truth.

Oh! I despise myself, that for a moment

(Pardon me, love!) could suffer mean suspicion

Usurp the seat of generous confidence.

Think all alike unjust, my Theodore,

When even thy Adelaide could join to wrong thee!

Jaq. Yet be advis'd——

Adel. Oh, leave me to my grief.—

To whom shall I complain? He but preserv'd

My life a little space, to make me feel

The extremes of joy and sorrow. Ere we met,

My heart was calm as the unconscious babe.

Enter Fabian.

Fab. Madam, my lord comes this way, and commands

To clear these chambers; what he meditates,

'Tis fit indeed were private. My old age

Has liv'd too long, to see my master's shame.

Adel. His shame, eternal shame! Oh, more than cruel!

How shall I smother it! Fabian, what means he?

My father—him I speak of—this young stranger—

Fab. My heart is rent in pieces: deaf to reason,

He hears no counsel but from cruelty.

Good Austin intercedes, and weeps in vain.

Adel. It is too much—Oh, Jaqueline!

Jaq. She faints;

Her gentle spirits could endure no more.

Ha! paler still! Fabian, thy arm; support her.

She stirs not yet.

Fab. Soft, bear her gently in.

[Adelaide is carried out.

Enter Count, followed by Austin.

Aust. I do believe thee very barbarous;

Nay, fear thy reason touch'd; for such wild thoughts,

Such bloody purposes, could ne'er proceed

From any sober judgment;—yet thy heart

Will sure recoil at this.

Count. Why, think so still;

Think me both ruffian-like, and lunatic;

One proof at least I'll give of temperate reason,—

Not to be baited from my fix'd design

By a monk's ban, or whining intercession.

Aust. Thou canst not mean to do it.

Count. Trust thine eyes.

Thybalt! bring forth the prisoner; bid my marshal

Prepare an axe. The ceremony's short;

One stroke, and all is past. Before he die,

He shall have leave to thank your godliness,

For speeding him so soon from this bad world.

Aust. Where is the right, the law, by which you doom him?

Count. My will's the law.

Count. I answer not to thee.

Aust. Answer to Heaven.

When call'd to audit in that sacred court,

Will that supremacy accept thy plea,

"I did commit foul murder, for I might?"

Count. Soar not too high; talk of the things of earth.

I'll give thee ear. Has not thy penitent,

Young Isabel, disclos'd her passion to thee?

Aust. Never.

Count. Just now, her coldness to my son,

You said, bespoke her heart preoccupied.

The frail and fair make you their oracles;

Pent in your close confessionals you sit,

Bending your reverend ears to amorous secrets.

Aust. Scoffer, no more! stop thy licentious tongue;

Turn inward to thy bosom, and reflect—

Count. That is, be fool'd. Yet will I grant his life,

On one condition.

Aust. Name it.

Count. Join my hand

To Isabel.

Aust. Not for the world.

Count. He dies.

Theodore brought in.

Come near, thou wretch! When call'd before me first,

With most unwonted patience I endur'd

Thy bold avowal of the wrong thou didst me;

A wrong so great, that, but for foolish pity,

Thy life that instant should have made atonement;

But now, convicted of a greater crime,

Mercy is quench'd: therefore prepare to die.

Theod. I was a captive long 'mongst infidels,

Whom falsely I deem'd savage, since I find

Even Tunis and Algiers, those nests of ruffians,

Might teach civility to polish'd France,

If life depends but on a tyrant's frown.

Count. Out with thy holy trumpery, priest! delay not,

Or, if he trusts in Mahomet, and scorns thee,

Away with him this instant.

Aust. Hold, I charge you!

Theod. The turban'd misbeliever makes some show

Of justice, in his deadly processes;

Nor drinks the sabre blood thus wantonly,

Where men are valued less than nobler beasts.—

Of what am I accused?

Count. Of insolence;

Of bold, presumptuous love, that dares aspire

To mix the vileness of thy sordid lees

With the rich current of a baron's blood.

Aust. My heart is touch'd for him.—Much injur'd youth,

Suppress awhile this swelling indignation;

Plead for thy life.

Theod. I will not meanly plead;

Nor, were my neck bow'd to his bloody block,

If love's my crime, would I disown my love.

Count. Then, by my soul, thou diest!

Theod. And let me die:

With my last breath I'll bless her. My spirit, free

From earth's encumbering clogs, shall soar above thee.

Anxious, as once in life, I'll hover round her,

Teach her new courage to sustain this blow,

And guard her, tyrant! from thy cruelty.

Count. Ha! give me way!

Aust. Why, this is madness, youth:

You but inflame the rage you should appease.

Theod. He thinks me vile. 'Tis true, indeed, I seem so:

But, though these humble weeds obscure my outside,

I have a soul, disdains his contumely;

A guiltless spirit, that provokes no wrong,

Nor from a monarch would endure it, offer'd:

Uninjur'd, lamb like; but a lion, rous'd.

Know, too injurious lord, here stands before thee,

The equal of thy birth.

Count. Away, base clod.—

Obey me, slaves.—What, all amaz'd with lies?

Aust. Yet, hear him, Narbonne: that ingenuous face

Looks not a lie. Thou saidst thou wert a captive—

Turn not away; we are not all like him.

Theod. My story's brief. My mother, and myself,

(I then an infant) in my father's absence,

Were on our frontiers seiz'd by Saracens.

Count. A likely tale! a well-devis'd imposture!

Who will believe thee?

Aust. Go on, say all.

Theod. To the fierce bashaw, Hamet,

That scourge and terror of the Christian coasts,

Were we made slaves at Tunis.

Aust. Ha! at Tunis?

Seiz'd with thy mother? Lives she, gentle youth?

Theod. Ah, no, dear saint! fate ended soon her woes,

In pity, ended! On her dying couch,

She pray'd for blessings on me.

Aust. Be thou blessed!

O fail not, nature, but support this conflict!

'Tis not delusion, sure. It must be he.—

But one thing more; did she not tell thee too,

Thy wretched father's name?

Theod. The lord of Clarinsal.

Why dost thou look so eagerly upon me?

If yet he lives, and thou know'st Clarinsal,

Tell him my tale.

Aust. Mysterious Providence!

Count. What's this? the old man trembles and turns pale. [Aside.

Theod. He will not let his offspring's timeless ghost

Walk unappeas'd; but on this cruel head

Exact full vengeance for his slaughter'd son.

Aust. O Giver of all good! Eternal Lord!

Am I so bless'd at last, to see my son?

Theod. Let me be deaf for ever, if my ears

Deceive me now! did he not say his son?

Aust. I did, I did! let this, and this, convince thee.

I am that Clarinsal; I am thy father.

Count. Why works this foolish moisture to my eyes? [Aside.

Down, nature! what hast thou to do with vengeance?

Theod. Oh, sir! thus bending, let me clasp your knees;—

Now, in this precious moment, pay at once

The long, long debt of a lost son's affection.

Count. [Aside.] Destruction seize them both! Must I behold

Their transports, ne'er, perhaps, again to know

A son's obedience, or a father's fondness!

Aust. Dear boy! what miracle preserved thee thus,

To give thee back to France?

Theod. No miracle,

But common chance. A warlike bark of Spain

Bore down, and seiz'd our vessel, as we rov'd

Intent on spoil: (for many times, alas!

Was I compell'd to join their hated league,

And strike with infidels.) My country known,

The courteous captain sent me to the shore;

Where, vain were my fond hopes to find my father:

'Twas desolation all: a few poor swains

Told me, the rumour ran he had renounc'd

A hated world, and here in Languedoc,

Devoted his remains of life to Heaven.

Aust. They told thee truth; and Heaven shall have my prayers,

My soul pour'd out in endless gratitude,

For this unhoped, immeasurable blessing.

Aust. And art thou so unskill'd in nature's language,

Still to mistrust us? Could our tongues deceive,

Credit, what ne'er was feign'd, the genuine heart:

Believe these pangs, these tears of joy and anguish.

Count. Or true, or false, to me it matters not.

I see thou hast an interest in his life,

And by that link I hold thee. Wouldst thou save him,

Thou know'st already what my soul is set on,

Teach thy proud heart compliance with my will:

If not—but now no more.—Hear all, and mark me—

Keep special guard, that none, but by my order,

Pass from the castle. By my hopes of heaven,

His head goes off, who dares to disobey me!

Farewell!——if he be dear to thee, remember.

[Exit Count.

Aust. If he be dear to me! my vital blood!

Image of her, my soul delighted in,

Again she lives in thee! Yes, 'twas that voice,

That kindred look, rais'd such strong instinct here,

And kindled all my bosom at thy danger.

Theod. But must we bear to be thus tamely coop'd

By such insulting, petty despotism?

I look to my unguarded side in vain;

Had I a sword——

Aust. Think not of vengeance now;

A mightier arm than thine prepares it for him.

Pass but a little space, we shall behold him

The object of our pity, not our anger.

Yes, he must suffer; my rapt soul foresees it:

Empires shall sink; the pond'rous globe of earth

Crumble to dust; the sun and stars be quench'd;

But O, Eternal Father! of thy will,

To the last letter, all shall be accomplish'd.

Theod. So let it be! but, if his pride must fall,

Ye saints, who watch o'er loveliness and virtue,

Confound not with his crimes, her innocence!

Make him alone the victim; but with blessings

Bright, and distinguish'd, crown his beauteous daughter,

The charming Adelaide, my heart's first passion!

Aust. Oh most disastrous love! My son, my son,

Thy words are poniards here. Alas! I thought

(So thought the tyrant, and for that he rag'd)

The vows exchang'd 'tween Isabel and thee,

Thwarted the issue of his wild designs.

Theod. I knew not Isabel, beyond a moment

Pass'd in surprise and haste.

Aust. O, had malignant fortune toil'd to blast him,

Thus had she snar'd him in this fatal passion!—

And does young Adelaide return thy love?

Theod. Bless'd powers, she does! How can you frown, and hear it!

Her generous soul, first touch'd by gratitude,

Soon own'd a kinder, warmer sympathy.

Soft as the fanning of a turtle's plumes,

The sweet confession met my enraptur'd ears.

Aust. What can I do?—Come near, my Theodore;

Dost thou believe my affection?

Theod. Can I doubt it?

Aust. Think what my bosom suffers, when I tell thee,

It must not, cannot be.

Theod. My love for Adelaide!

Aust. Deem it delicious poison; dash it from thee:

Thy bane is in the cup.

Theod. O bid me rather

Tear out my throbbing heart; I'd think it mercy,

To this unjust, this cruel interdiction.

That proud, unfeeling Narbonne, from his lips

Well might such words have fallen;—but thou, my father——

Aust. And fond, as ever own'd that tender name.

Not I, my son, not I prevent this union,

To me 'tis bitterness to cross thy wish,

But nature, fate, and Heaven, all, all forbid it.

We must withdraw, where Heaven alone can hear us:

Then must thou stretch thy soul's best faculties;

Call every manly principle to steel thee;

And, to confirm thy name, secure thy honour,

Make one great sacrifice of love to justice.

[Exeunt.

A Chamber.

Adelaide discovered.

Adel. Woe treads on woe.—Thy life, my Theodore,

Thy threaten'd life, snatch'd from the impending stroke,

Just gave a moment's respite to my heart;

And now a mother's grief, with pangs more keen,

Wakes every throbbing sense, and quite o'erwhelms me.

Her soul wrapp'd up in his, to talk thus to her!

Divorce her, leave her, wed with Isabel,

And call on Heaven, to sanctify the outrage!

How could my father's bosom meditate

What savage tongues would falter even to speak?

But see, he comes——

Enter Austin and Jaqueline.

O let me bend to thank you;

In this extreme distress, from you alone

(For my poor heart is vain) can she hope comfort.

Aust. How heard she the ill tidings? I had hopes

His cooler reason would subdue the thought;

And Heaven, in pity to her gentle virtues,

Might spare her knowing, how he meant to wrong them.

Jaq. The rumour of the castle reach'd her first;

But his own lips confirm'd the barbarous secret.

Sternly, but now, he enter'd her apartment,

And, stamping, frown'd her women from her presence!

After a little while they had pass'd together,

His visage flush'd with rage and mingled shame,

He burst into the chamber where we waited,

Bade us return, and give our lady aid;

Then, covering his face with both his hands,

Went forth like one half-craz'd.

Adel. Oh good, kind father!

There is a charm in holy eloquence

(If words can medicine a pang like this)

Perhaps may sooth her. Sighs, and trickling tears,

Are all my love can give. As I kneel by her,

She gazes on me, clasps me to her bosom;

Cries out, My child! my child! then, rising quick,

Severely lifts her streaming eyes to heaven;

Laughs wildly, and half sounds my father's name;

Till, quite o'erpower'd, she sinks from my embrace,

While, like the grasp of death, convulsions shake her.

Aust. Remorseless man! this wound would reach her heart,

And when she falls, his last, best prop, falls with her,

And see, the beauteous mourner moves this way:

Time has but little injur'd that fair fabric;

But cruelty's hard stroke, more fell than time,

Works at the base, and shakes it to the centre.

Enter the Countess.

Countess. Will then, these dreadful sounds ne'er leave my ears?

Our marriage was accurs'd; too long we have liv'd

"In bonds forbid; think me no more thy husband;

The avenging bolt, for that incestuous name,

Falls on my house, and spreads the ruin wide."

These were his words.

Adel. Oh, ponder them no more!

Lo! where the blessed minister of peace,

He, whose mild counsels wont to charm your care,

Is kindly come to cheer your drooping soul;

And see, the good man weeps.

Countess. What! weep for me?

Aust. Ay, tears of blood from my heart's inmost core,

And count them drops of water from my eyes,

Could they but wash out from your memory

The deep affliction, you now labour with.

Countess. Then still there is some pity left in man:

I judg'd you all by him, and so I wrong'd you.

I would have told my story to the sea,

When it roar'd wildest; bid the lioness,

Robb'd of her young, look with compassion on me;

Rather than hoped in any form of man,

To find one drop of human gentleness.

Aust. Most honour'd lady!—

Aust. What slanderous tongue dare thus profane your virtue?

Madam, I know you well; and, by my order,

Each day, each hour, of your unspotted life,

Might give as fair a lesson to the world,

As churchmen's tongues can preach, or saints could practise.

Countess. He charges me with all—Thou, poor Hortensia!

What guilt, prepost'rous guilt, is thine to answer!

Adel. In mercy, wound not thus your daughter's soul.

Aust. A villain or a madman might say this.

Countess. What shall I call him? He, who was my husband;

My child, thy father;—He'll disclaim thee too.

But let him cast off all the ties of nature,

Abandon us to grief and misery—

Still will I wander with thee o'er the world:

I will not wish my reason may forsake me,

Nor sweet oblivious dulness steep my sense,

While thy soft age may want a mother's care,

A mother's tenderness, to wake and guard thee.

Adel. And, if the love of your dear Adelaide,

Her reverence, duty, endless gratitude

For all your angel goodness, now can move you,

Oh, for my sake (lest quite you break my heart)

Wear but a little outside show of comfort;

A while pretend it, though you feel it not,

And I will bless you for deceiving me.

Countess. I know 'tis weakness—folly, to be mov'd thus;

And these, I hope, are my last tears for him.

Alas, I little knew, deluded wretch!

His riotous fancy glow'd with Isabel;

That not a thought of me possess'd his mind,

But coldness and aversion; how to shun me,

And turn me forth a friendless wanderer.

Aust. Lady, for your peace,

Think, conscience is the deepest source of anguish:

A bosom, free like yours, has life's best sunshine;

'Tis the warm blaze in the poor herdsman's hut;

That, when the storm howls o'er his humble thatch,

Brightens his clay-built walls, and cheers his soul.

Countess. O father, reason is for moderate sorrows;

For wounds which time has balm'd; but mine are fresh,

All bleeding fresh, and pain beyond my patience.

Ungrateful! cruel! how have I deserv'd it?

Thou tough, tough heart, break for my ease at once!

Aust. I scarce, methinks, can weigh him with himself;

Vexations strange, have fallen on him of late!

And his distemper'd fancy drives him on

To rash designs, where disappointment mads him.

Countess. Ah no! his wit is settled, and most subtle;

Pride and wild blood are his distemper, father.

But here I bid farewell to grief and fondness:

Let him go kneel, and sigh to Isabel:

And may he as obdurate find her heart,

As his has been to me.

Aust. Why, that's well said;—

'Tis better thus, than with consuming sorrow

To feed on your own life. Give anger scope:

Time, then, at length, will blunt this killing sense;

And peace, he ne'er must know again, be yours.

Countess. I was a woman, full of tenderness;

I am a woman, stung by injuries.

Narbonne was once my husband—my protector;

He was—what was he not?—He is my tyrant;

The unnatural tyrant of a heart, that lov'd him.

With cool, deliberate baseness, he forsakes me;

With scorn as steadfast shall my soul repay it.

Aust. You know the imminent danger threatens him,

From Godfrey's fearful claim?

Countess. Too well I know it;

A fearful claim indeed!

Aust. To-morrow's sun

Will see him at these gates; but trust my faith,

No violence shall reach you. The rash count

(Lost to himself) by force detains me here.

Vain is his force:—our holy sanctuary,

Whate'er betides, shall give your virtue shelter;

And peace, and piety, alone, approach you.

Countess. Oh, that the friendly bosom of the earth

Would close on me for ever!

Aust. These ill thoughts

Must not be cherish'd. That all righteous Power,

Whose hand inflicts, knows to reward our patience:

Farewell! command me ever as your servant,

And take the poor man's all, my prayers and blessing.

[Exit Austin.

Adel. Will you not strive to rest? Alas! 'tis long,

Since you have slept. I'll lead you to your couch;

And gently touch my lute, to wake some strain,

May aid your slumbers.

Countess. My sweet comforter!

I feel not quite forlorn, when thou art near me.

Adel. Lean on my arm.

Countess. No, I will in alone.

My sense is now unapt for harmony.

But go thou to Alphonso's holy shrine;

There, with thy innocent hands devoutly rais'd,

Implore his sainted spirit, to receive

Thy humble supplications; and to avert

From thy dear head, the still impending wrath,

For one black deed, that threatens all thy race.

[Exit Countess.

Adel. For thee my prayers shall rise, not for myself,

And every kindred saint will bend to hear me.

But, O my fluttering breast!—'Tis Theodore!

How sad, and earnestly, he views that paper!

It turns him pale. Beshrew the envious paper!

Why should it steal the colour from that cheek,

Which danger ne'er could blanch? He sees me not.

I'll wait; and should sad thoughts disturb his quiet,

If love has power, with love's soft breath dispel them.

[Exit Adelaide.

Enter Theodore, with a Paper.

Theod. My importunity at last has conquer'd:

Weeping, my father gave, and bade me read it.

"'Tis there," he cried, "the mystery of thy birth;

There, view thy long divorce from Adelaide."

Why should I read it? Why with rav'nous haste

Gorge down my bane? The worst is yet conceal'd;

Then wherefore, eager for my own destruction?

Inquire a secret, which, when known, must sink me?

My eye starts back from it; my heart stands still;

And every pulse, and motion of my blood,

With prohibition, strong as sense can utter,

Cries out, "Beware!"—But does my sight deceive?

Is it not she? Up, up, you black contents:

A brighter object meets my ravish'd eyes.

Now let the present moment, love, be thine!

For ill, come when it may, must come untimely.

Enter Adelaide.

Adel. Am I not here unwish'd for?

Adel. O Theodore! what wondrous turns of fortune

Have given thee back to a dear parent's arms?

And spite of all the horrors which surround me,

And worse, each black eventful moment threatens,

My bosom glows with rapture at the thought

Thou wilt at last be bless'd.

Theod. But one way only

Can I be bless'd. On thee depends my fate.

Lord Raymond, harsh and haughty as he is,

And adverse to my father's rigid virtue,

When he shall hear our pure, unspotted vows,

Will yield thee to my wishes;—but, curs'd stars!

How shall I speak it?

Adel. What?

Theod. That holy man,

That Clarinsal, whom I am bound to honour,

Perversely bids me think of thee no more.

Adel. Alas! in what have I offended him?

Theod. Not so; he owns thy virtues, and admires them.

But with a solemn earnestness that kills me,

He urges some mysterious, dreadful cause,

Must sunder us for ever.

Adel. Oh, then fly me!

I am not worth his frown; begone this moment;

Leave me to weep my mournful destiny,

And find some fairer, happier maid, to bless thee.

Theod. Fairer than thee! Oh, heavens! the delicate hand

Of nature, in her daintiest mood, ne'er fashion'd

Beauty so rare. Love's roseate deity,

Fresh from his mother's kiss, breath'd o'er thy mould

That soft, ambrosial hue,—Fairer than thee!

'Twere blasphemy in any tongue but thine,

So to disparage thy unmatch'd perfections.

Adel. No, Theodore, I dare not hear thee longer;

Perhaps, indeed, there is some fatal cause.

Theod. There is not, cannot be. 'Tis but his pride,

Stung by resentment 'gainst thy furious father—

Adel. Ah no; he is too generous, just, and good,

To hate me for the offences of my father.

But find the cause. At good Alphonso's tomb

I go to offer up my orisons;

There bring me comfort, and dispel my fears;

Or teach me, (oh, hard thought!) to bear our parting.

[Exit Adelaide.

Theod. She's gone, and now, firm fortitude, support me!

For here I read my sentence; life or death.

[Takes out the Paper.

Thou art the grandson of the good Alphonso,

And Narbonne's rightful lord.—Ha! is it so?

Then has this boist'rous Raymond dar'd insult me,

Where I alone should rule:—yet not by that

Am I condemn'd to lose her. Thou damn'd scroll!

I fear thou hast worse poison for my eyes.

Long were the champions, bound for Palestine,

(Thy grandsire then their chief,) by adverse winds

Detain'd in Naples; where he saw, and lov'd,

And wedded secretly, Vicenza's daughter;

For, till the holy warfare should be clos'd,

They deem'd it wise to keep the rite conceal'd.

The issue of that marriage was thy mother;

But the same hour that gave her to the world,

For ever clos'd the fair one's eyes who bore her.

Foul treason next cut short thy grandsire's thread;

Poison'd he fell.—

[Theodore pauses, and Austin, who has been some time behind, advances.

Aust. By Raymond's felon father,

Who, adding fraud to murder, forg'd a will,

Devising to himself and his descendants,

Thy rights, thy titles, thy inheritance.

Theod. Then I am lost—

Aust. Now think, unkind young man,

Was it for naught I warn'd thee to take heed,

And smother in its birth this dangerous passion?

The Almighty arm, red for thy grandsire's murder,

Year after year has terribly been stretch'd

O'er all the land, but most this guilty race.

Theod. The murderer was guilty, not his race.

Aust. Great crimes, like this, have lengthen'd punishments.

Why speak the fates by signs and prodigies?

Why one by one falls this devoted line,

Accomplishing the dreadful prophecy,

That none should live to enjoy the fruits of blood?

But wave this argument.—Thou wilt be call'd

To prove thy right,

By combat with the Count.

Theod. In arms I'll meet him;

To-morrow, now.—

Aust. And, reeking with his blood,

Offer the hand, which shed it, to his daughter?

Theod. Ha!

Aust. Does it shake thee?——Come, my Theodore,

Let not a gust of love-sick inclination

Root, like a sweeping whirlwind, from thy soul

All the fair growth of noble thoughts and virtue,

Thy mother planted in thy early youth;

Oh, rashly tread not down the promis'd harvest,

They toil'd to rear to the full height of honour!

Theod. Would I had liv'd obscure in penury,

Rather than thus!—Distraction!—Adelaide!

Enter Adelaide.

Adel. Oh, whither shall I fly!

Theod. What means my love?

Why thus disturb'd?

Adel. The castle is beset;

The superstitious, fierce, inconstant people,

Madder than storms, with weapons caught in haste,

Menace my father's life; rage, and revile him;

Call him the heir of murderous usurpation;

And swear they'll own no rightful lord but Godfrey.

Aust. Blind wretches! I will hence, and try my power

To allay the tumult. Follow me, my son!

[Exit Austin.

Adel. Go not defenceless thus; think on thy safety,

See, yonder porch opes to the armoury;

There coats of mailed proof, falchions, and casques,

And all the glittering implements of war,

Stand terribly arrang'd.

Theod. Heavens! 'twas what I wish'd.

Yes, Adelaide, I go to fight for him:

Thy father, shall not fall ingloriously;

But, when he sees this arm strike at his foes,

Shall own, thy Theodore deserv'd his daughter.

[Exeunt.

A Hall.

Enter Count, Fabian, Austin, Attendants with Prisoners.

Count. Hence to a dungeon with those mutinous slaves;

There let them prate of prophecies and visions;

And when coarse fare and stripes bring back their senses,

Perhaps I may relent, and turn them loose

To new offences, and fresh chastisement.

[Exeunt Officers, &c.

Fab. You bleed, my lord!

Count. A scratch—death! to be bay'd

By mungrels! curs! They yelp'd, and show'd their fangs,

Growl'd too, as they would bite. But was't not poor,

Unlike the generous strain of Godfrey's lineage,

To stir the rabble up in nobles' quarrels,

And bribe my hinds and vassals to assault me.

Aust. They were not stirr'd by Godfrey.

Aust. I might, perhaps, have look'd for better thanks,

Than taunts to pay my service.—But no matter.—

My son, too, serv'd thee nobly; he bestrode thee,

And drove those peasants back, whose staves and clubs,

But for his aid, had shiver'd that stout frame:

But both, too well accustom'd to thy transports,

Nor ask, nor hope thy courtesy.

Count. Your pardon!

I knew my life was sav'd, but not by whom;

I wish'd it not, yet thank him. I was down,

Stunn'd in the inglorious broil; and nought remember,

More than the shame of such a paltry danger.

Where is he?

Aust. Here.

[Theodore advances from the Back of the Stage.

Count. [Starting.] Ha! angels shelter me!

Theod. Why starts he thus?

Count. Are miracles renew'd?

Art thou not ris'n from the mould'ring grave?

And in the awful majesty of death,

'Gainst nature, and the course of mortal thought,

Assum'st the likeness of a living form,

To blast my soul with horror?

Theod. Does he rave?

Or means he thus to mock me?

Count. Answer me!

Speak, some of you, who have the power to speak;

Is it not he?

Fab. Who, good my lord?

Count. Alphonso.

His form, his arms, his air, his very frown.

Lord of these confines, speak—declare thy pleasure;

Theod. Dost thou not know me then?

Count. Ha! Theodore?

This sameness, not resemblance, is past faith.

All statues, pictures, or the likeness kept

By memory, of the good Alphonso living,

Are faint and shadowy traces, to this image!

Fab. Hear me, my lord, so shall the wonder cease.—

The very arms he wears, were once Alphonso's.

He found them in the stores, and brac'd them on,

To assist you in your danger.

Count. 'Tis most strange.

I strive, but cannot conquer this amazement:

I try to take them off; yet still my eyes

Again are drawn, as if by magic on him.

Aust. [Aside to Theodore.] Hear you, my son?

Theod. Yes, and it wakes within me,

Sensations new till now.

Aust. To-morrow's light

Will show him wonders greater.—Sir, it pleas'd you,

(Wherefore you best can tell) to make us here

Your prisoners; but the alarm of your danger

Threw wide your gates, and freed us. We return'd

To give you safeguard.—May we now depart?

Count. Ay, to the confines of the farthest earth;

For here thy sight unhinges Raymond's soul.

Be hid, where air or light may never find thee;

And bury too that phantom.

[Exit Count, with his Attendants.

Theod. Insolence!

Too proud to thank our kindness! yet, what horror

Shook all his frame, when thus I stood before him!

Aust. The statue of thy grandsire

(The very figure as thou stood'st before him,

Arm'd just as thou art), seem'd to move, and live;

That breathing marble, which the people's love

Rear'd near his tomb, within our convent's walls.

Anon I'll lead thee to it.

Theod. Let me hence,

To shake these trappings off.

Aust. Wear them, and mark me.

Ere night, thy kinsman Godfrey, will be master

Of all thy story:—

He is brave, and just,

And will support thy claim. Should proof and reason

Fail with the usurper, thou must try thy sword

(And Heaven will strike for thee) in combat with him.

The conscious flash of this thy grandsire's mail,

Worse than the horrors of the fabled Gorgon,

That curdled blood to stone, will shrink his sinews,

And cast the wither'd boaster at thy feet.

Theod. Grant it ye powers! but not to shed his blood:

The father of my Adelaide, that name—

Aust. Is dearer far than mine;—my words are air;

My counsels pass unmark'd. But come, my son!

To-night my cell must house thee. Let me show thee

The humble mansion of thy lonely father,

Proud once, and prosperous; where I have wept, and pray'd,

And, lost in cold oblivion of the world,

Twice nine long years; thy mother, and thyself,

And God, were all my thoughts.

Theod. Ay, to the convent!

For there my love, my Adelaide, expects me. [Aside.

[Exeunt.

Another Apartment in the Castle.

Enter Count and Fabian.

Count. By hell, this legend of Alphonso's death

Hourly gains ground.

Fab. They talk of naught besides;

And their craz'd notions are so full of wonder,

There's scarce a common passage of the times,

But straight their folly makes it ominous.

Count. Fame, that, like water, widens from its source,

Thus often swells, and spreads a shallow falsehood.

At first, a twilight tale of village terror,

The hair of boors and beldams bristled at it;

(Such bloodless fancies wake to nought but fear:)

Then, heard with grave derision by the wise,

And, from contempt, unsearch'd and unrefuted,

It pass'd upon the laziness of faith,

Like many a lie, gross, and impossible.

Fab. A lie believ'd, may in the end, my lord,

Prove fatal as a written gospel truth.

Therefore——

Count. Take heed; and ere the lightning strike,

Fly from the sulphurous clouds.—I am not dull;

For, bright as ruddy meteors through the sky,

The thought flames here, shall light me to my safety.

Fabian, away! Send hither to me straight,

Renchild and Thybalt. [Exit Fabian.] They are young and fearless.

Thy flight, ungrateful Isabel, compels me

To this rude course. I would have all with kindness;

Nor stain the snow-white flower of my true love

With spots of violence. But it must be so.

This lordly priest, this Clarinsal, or Austin,

Like a true churchman, by his calling tainted,

Prates conscience; and in craft abets Earl Godfrey,

That Isabel may wed his upstart son.

Let Rome dart all her lightnings at my head,

Till her grey pontiff singe in his own fires:

Spite of their rage, I'll force the sanctuary,

And bear her off this night, beyond their power;

My bride, if she consents; if not, my hostage.

Enter Two Officers.

Come hither, sirs. Take twenty of your fellows;

Post ten at the great gate of Nicholas;

The rest, by two's, guard every avenue

Leads from the convent to the plain or castle.

Charge them (and as their lives shall answer it,)

That none but of my train pass out, or enter.

1 Offi. We will, my lord, about it instantly.

Count. Temper your zeal, and know your orders first.

Take care they spill no blood:—no violence,

More than resisting who would force a passage:

The holy drones may buzz, but have no stings.

I mean to take a bawble from the church,

A reverend thief stole from me. Near the altar,

(That place commands the centre of the aisle)

Keep you your watch. If you espy a woman

(There can be only she), speed to me straight;

You'll find my station near Alphonso's porch.

Be swift as winds, and meet me presently.

[Exeunt severally.

The inside of a Convent, with Aisles and Gothic Arches; Part of an Altar appearing on one side; the Statue of Alphonso, in Armour, in the centre. Other Statues and Monuments also appearing. Adelaide veiled, rising from her knees before the Statue of Alphonso.

Adel. Alas! 'tis mockery to pray as I do.

Thoughts fit for heaven, should rise on seraphs' wings,

Unclogg'd with aught of earth; but mine hang here;

Beginning, ending, all in Theodore.

Why comes he not? 'Tis torture for the unbless'd,

To suffer such suspense as my heart aches with.

What can it be,—this secret, dreadful cause,

This shaft unseen, that's wing'd against our love?

Perhaps—I know not what.—At yonder shrine

Bending, I'll seal my irrevocable vow:

Hear, and record it, choirs of saints and angels!

If I am doom'd to sigh for him in vain,

No second flame shall ever enter here;

But, faithful to thy fond, thy first impression,

Turn thou, my breast, to every sense of joy,

Cold as the pale-ey'd marbles which surround me.

[Adelaide withdraws.

Enter Austin and Theodore.

Theod. And may the Power, which fashion'd thus my outside,

With all his nobler ornaments of virtue

Sustain my soul! till generous emulation

Raise me, by deeds, to equal his renown,

And—

Aust. To avenge him. Not by treachery,

But, casting off all thoughts of idle love,

Of love ill-match'd, unhappy, ominous,—

To keep the memory of his wrongs; do justice

To his great name, and prove the blood you spring from.