The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Nursery, March 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Nursery, March 1881, Vol. XXIX

A Monthly Magazine for Youngest Readers

Author: Various

Release Date: September 14, 2012 [EBook #40754]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, MARCH 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

| PAGE | |

| Telling a Story | 65 |

| Turtles | 71 |

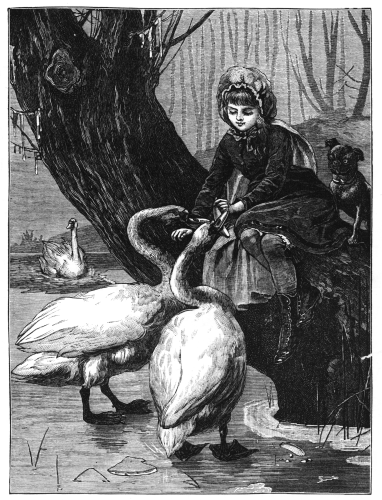

| Feeding the Swans in Winter | 72 |

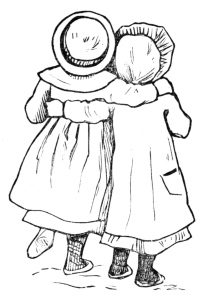

| Two Friends | 74 |

| The Swallows' Nest | 76 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 81 |

| The Faithful Sentinel | 86 |

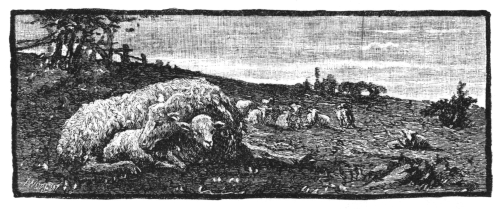

| Bruce and Old Sheepy | 88 |

| Elfrida's Present | 92 |

| "Parley-voo" | 93 |

| PAGE | |

| To the Snowdrop | 69 |

| Rather Bashful | 72 |

| Bird, Lamb, Baby | 75 |

| The Gentleman in Gray | 78 |

| The Little Scholars | 80 |

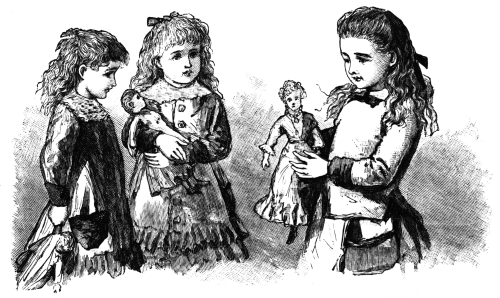

| The Three Dolls | 82 |

| "Right of Way" | 91 |

| Winter (with music) | 96 |

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 3.

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 3.

"When I was a girl, and wanted to hear a story, and the grown-up people didn't feel like telling me one, they would say,—

"Now, every time this was said to me, I would think that I really should hear the story about Jack O'Nory, or the other one about Jack and his brother. But it was always the same; just as I thought the story was coming, I would hear, instead, 'And now my story's done.'

"One day, when I begged for one of the stories, my aunt told me that I couldn't hear about Jack O'Nory or his brother, because Mother Goose never told the stories about them; that she just began, and then thought better of it. After that I didn't ask any more; but I said to myself, 'If ever I get big, I'll find out those stories.' And so, sure enough, I did. And I am going to tell one of them now,—the one about Jack O'Nory himself.

"'It is a story that all came of his having a great liking for buns. Jack lived in the next house to Mother Goose, and every morning, if she peeped between the curtains, she was sure to see Jack waiting on the pavement for the bun-man. You see the bun-man went around very early, so that people could have their buns for breakfast.

"'But one morning Jack slept too late, and, when he ran out, the bun-man had already gone by and was almost out of sight. Jack ran after him, but could not catch him.

"'It didn't seem to Jack a bit nice, not to have any bun with his milk that morning; and so all day Jack kept saying to himself, "That bun-man won't get by the house to-morrow morning without my knowing it, I guess!" And this was the last thing he thought of as he took off his shoes and stockings at night before the fire.

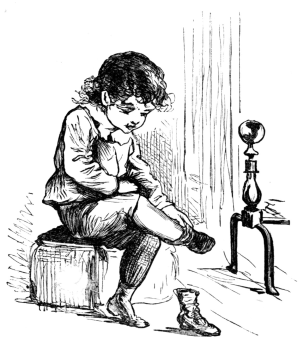

"'But all his thinking did not seem to be of much use; for, before he had slept half as long as he wanted to, he heard the jingle of the bun-man's bell. Up he jumped, pulled on his clothes as fast as he could, and had got on all except one shoe, when the bell rang below the window. Down he ran, but the bun-man wasn't there.

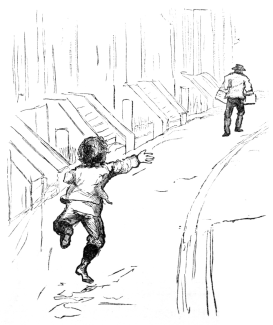

"'Jack forgot that he had on only one shoe, and started to run after the man. He was soon only half a square behind him; but just then the man turned a corner, and was out of sight. Jack turned the corner too; but the man had walked fast and was just turning another corner.

"'Poor Jack began to think he was not going to get his bun; but he still ran on, and turned the next corner and the next, for the bun-man seemed to be always turning corners. Jack got very hot, and was just beginning to cry, when, as he was turning the ninth corner after the man, he saw him go into a house.

"'"Ah!" thought Jack, "that's the place where they make the buns. I'll hurry in after him, and then I'll surely get my bun, and he'll tell me the way home besides."

"'So in went Jack. But the man was not to be seen. There was nothing to be seen except buns, all in great piles like walls, and all smoking hot. Jack was very warm already, you know, and the steam from so many hot buns made him warmer still; but he tried not to mind it, and walked on, looking all the time for the bun-man.

"'He could hear his bell every little while; but the more he tried to[68] go where the bell was, the more he could not find it, Jack by this time, had gone through so many rooms, that he did not know how to get out: so he went down some stairs that he saw ahead of him, and found himself in the place where the buns were baked.

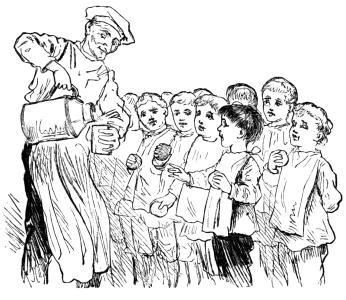

"'There were plenty of men here, all in baker's caps; but instead of making buns, they were pouring out milk for two rows of little boys, who stood, each with a bib under his chin and a bun in his hand. The strangest part of it was that the boys did not seem to be a bit hot, while poor Jack was almost melting. Jack thought that if he could only drink some milk, he should feel better.

"'But just as he was about to take his place with the rest of the boys, they disappeared, and instead of pouring out milk, the men were shovelling buns out of ovens on all sides of the room. Now, Jack had heard his mamma tell about the great oven that buns were baked in, and he had always wanted to see one: so he ran up to the door to look in.

"'The heat drove him back, and he turned quickly to run, just as one of the bakers was putting his shovel in for more buns. The baker did not notice him, and, the first thing Jack knew, the baker's elbow drove him bump against the oven door. My! how he screamed!

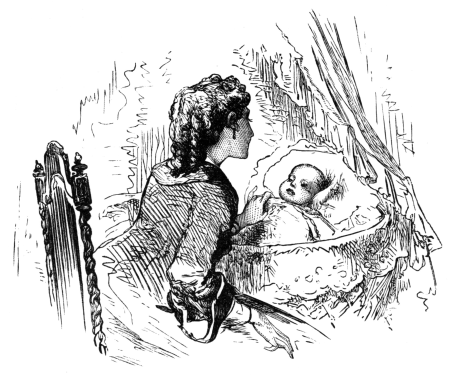

"'Then, all of a sudden, there was no oven to be seen, only a fire; and his mother was coming in at the door,—not the bun-man's door, but his own nursery door,—saying, "Why, Jack, not undressed yet! I sent you to bed a half-hour ago!"

"'But she stopped suddenly, and picked Jack up, hugging and kissing him, and calling his father to go for the doctor. Poor Jack! what with the hurt on his head, and his mother's crying, and the thought of the strange bake-shop, he wondered whether he was Jack O'Nory at all.[69]

"'While he was wondering the doctor came, and his mother began to tell him about Jack's hurt. "You see, doctor," she said, "my little boy went to sleep as he was sitting very near the fire, and fell over and cut his head against the hot andiron."

"'Then Jack knew that the bun-man, the bake-shop, and the oven, were all a dream. He told his mamma the dream, and she promised him three buns every day till his head was well. Then she tucked him up in his bed, and told him not to dream of the bun-man again.'

"So this is the story of Jack O'Nory. Some day 'I'll tell you another about Jack and his brother, and now my story is done!'"

Snow-piercer, cloud-gazer, wind-scorner, eye-cheerer,

Bring to my heart thy dear message yet nearer. When age or sorrow is darkly impending, Snows of adversity thickly descending, Then, springing out of them, checked by no blasting, Let there bloom thoughts of the life everlasting. Coming, like snow-drops, amid our endurance, Bringing to each weary heart the assurance, To joy's frozen waste spring draws nigher and nigher, And death is the way to life higher and higher.

EPES SARGENT. |

When I put him on the floor or ground, he would stay quite still, and draw in his head and legs, until I turned away, or busied myself with something else; then he would make off as fast as his little legs would carry him.

I once lost one in that way: so, now that I know their tricks, I am more careful. But certainly that turtle must have had some sense to be able to tell when my back was turned, or even when I was not looking.

Their habits are quite peculiar. In summer they stay in the water most of the time, coming out only now and then to sun themselves on some log or branch. In the winter they bury themselves in the mud, or remain in a torpid state. When spring comes, they lay their eggs.

They live chiefly on bugs; but I have heard of one living a whole year without any thing to eat. They are very patient, and I have seen one try for hours to get over a wall that one would think he could never get over; and yet he would succeed.

I have a turtle now that will have a funny story to tell his friends, if he ever reaches his native home again. This is it: I once took him to school with me, and left him in a box, with the cover half open, on a table in the dressing-room. In about an hour I heard a suppressed laugh from one of the girls, and, looking up, I saw Mr. Turtle calmly walking into school. He wanted to learn something as well as the rest of us.

|

Under this great sunbonnet

Is hid a pretty face, Belonging to a little girl Whose name, they say, is Grace. She is a merry little girl, As good as good can be; But she is rather bashful, As any one may see.

W. |

The swans are often fed by girls and boys in the summer; but in winter they have few visitors: so they are glad to see Mary, and waddle up on the ice to meet her.

She feeds them with something that looks to me like a[73] banana, and they eat it greedily. Pug looks on fiercely, as though he did not quite approve of their doings, and had half a mind to interfere.

Take care, Pug: you had better keep in the background. A blow from a swan's wing would not be good fun to a small dog. Let the swans eat their luncheon in peace.

Jane and Ann were good friends, but one morning they had a quarrel. They soon made it up. Jane put her arms round Ann's neck, and said, "I am sorry." Ann gave her a kiss, and they were friends again.

Here you see them taking a walk. They have on good warm coats, for it is a very cold day. Just see how lovingly they clasp each other. They are having a nice little chat. I wonder what they are saying.

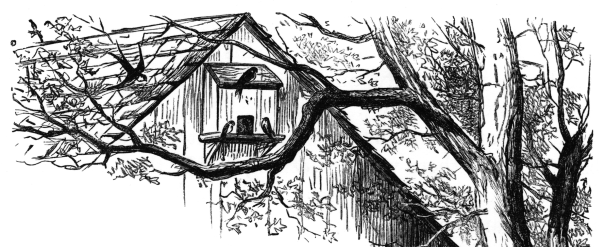

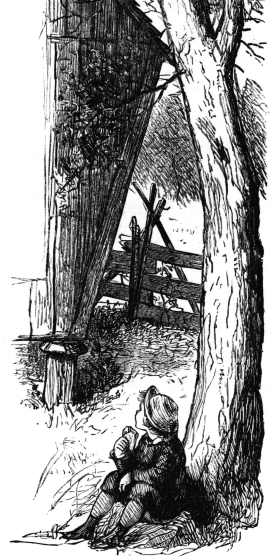

There were no playmates for Charley at grandpa's; but with a calf at the barn, several broods of chickens, and four[77] kittens, he found enough to occupy his mind. He was up very early in the morning, and it was after ten o'clock when he came into the kitchen rather hungry.

"Look under the cloth on the table, Charley," called his grandma from the sitting-room. "You'll find a little cake I baked for you. Don't you see it?" she asked, coming into the kitchen. "There, that one."

"Oh!" said Charley, "I thought that was a loaf."

Then, taking the cake in his hand, he sat on a rock at the foot of a tree a little distance from the house, and began to eat with great relish.

Not far from him, and a little way from the other buildings, was the corn-barn, and at one end of its roof was a bird-house, which had been taken by two little birds for their home. Charley saw one bird come out and fly away. While she was gone, her mate kept watch at a short distance to see that no harm came to the eggs that were within.[78]

Charley noticed, that, in flying, these birds had different motions from the sparrows and robins which lived about his own home in the city, and, when he went nearer, he saw that they were swallows.

As he watched them pass in and out of their house, he observed that there was something inside that opened and shut like a door. It was pressed back when the birds went in, and sprang into place again as soon as they were inside. Charley could not make out what it was, and ran to the house to ask about it.

"Grandma," he said, "is there a real door to the swallows' house?"

"They make one for themselves," she answered: "there is no door to the box. You know their house stands where it is exposed to all the winds, and, on some days since they came, they must have felt the cold very much. But I saw one come flying home one day with a turkey's feather in his beak, and they worked away at it very busily until they had placed it as you see. It keeps out the wind, and makes the house much more comfortable."

Charley went back to look at the door again, and wished he could be small enough, for a few minutes, to go inside the bird-house, and see just how it was fastened. But he could not have his wish, and the swallows kept their secret.

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

It was more than a hundred years ago that this trusted guard did duty; and when he died, not a drum was heard, and no soldiers fired a volley over his grave. You cannot find his name on the roll of enlisted men; and yet no soldier was ever more faithful.

There was war with the Indians at the time of which I write, and a family of settlers lived in what is now the State of Maine, on the bank of the River Androscoggin. One day the children of the family went down by the river to pick berries.

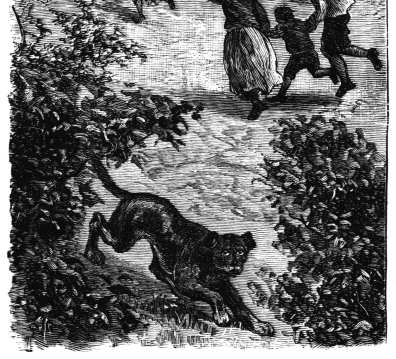

With the little party of boys and girls went the family dog. He was trained to follow the trail of Indians, and to give warning of their approach. The watchful dog took his place, like a sentinel, near the children, while they ran about from bush to bush, eating more berries than went into the pail.

Suddenly the dog gave a low growl, and looked angrily toward a heap of brush at the edge of the woods. The children knew what that meant, and, without waiting to see what the danger was, they ran at once towards the block-house.

The faithful dog did not run, but stood on guard to meet the Indian whom he had seen coming from the thicket. It was not far to the house; and the children were soon in a place of safety, while the Indian skulked back to the woods.

Several years after, when the war was all over, this very same Indian came that way, and talked with the children. They treated him kindly, and he became their good friend. But he often told them of the danger they all were in, that afternoon, when the good dog gave them such timely warning.

The dog lived to a good old age, and was loved and petted by the family as long as he lived; and to this day the descendants of Enoch and Esther, Martha and Samuel, the children saved by the dog, tell the story that I have related, and speak gratefully of the faithful sentinel.

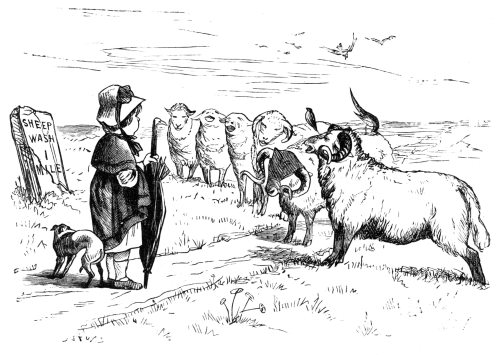

In the basement of the farm-house was a huge churn, the handle of which was attached to a large barrel made of slats, in such a way, that, when the barrel revolved, the churn was worked. When the dairy-maid was ready to churn, she would lock Bruce, their great dog, into this barrel, and say to him, "Go on, Bruce." If he went on, at every step he turned the barrel. The faster the barrel turned, the faster the churn-handle moved up and down, and the sooner the butter came.

Bruce did not like this kind of work; and who of us would? He often tried to shirk it by running away; but when John, the farmer's son, perceived this trick, he took care to secure the dog over night. The farmer and his son were very good to their animals: so, in order that Bruce might rest, they selected a sheep to perform a part of the labor. This sheep, though quite young, was never called by any other name than "Old Sheepy."

The dog and the sheep took turns in the churning thus: Bruce worked Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays; Old Sheepy worked the other three days of the six. On Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday mornings, Old Sheepy could never be found without much hunting. The other three mornings she would leisurely wander near the house, nibbling the grass near the doorstep.

So John was obliged to drive her into an enclosure, and there confine her for the night, previous to her churning, as it took too much time to find her in the morning.

One Monday evening, Bruce, having done his day's work, was lying on a rug in the sitting-room, where the farmer's children and myself were having a quiet game of "Come, d'ye come?" At eight o'clock, Priscilla and John, as if with one thought, started up from the game with the words, "Has any one shut up Old Sheepy?" No one knew. So off John ran to get the animal, but soon returned, not able to find her.

"No matter," said Priscilla, "Bruce has had an easy time to-day. We'll put him on to-morrow; for we never had more cream ready than now." Bruce pricked up his ears, as if to say, "Catch me churning Old Sheepy's butter!"

When bed-time came, Priscilla said, "I will not let old Bruce out to-night. I will put him in the wash-room." Priscilla didn't quite know Bruce, if she thought he was simple enough to be caught napping after hearing that. He got out, no one knew how; and there was nothing to to be done but to wait patiently till morning.

Bruce had no idea of allowing Old Sheepy to get clear of her task. At midnight a terrible barking and bleating and growling and scampering, was heard some little distance from the house. John went out to see what the noise was about. He found that Bruce had spied Old Sheepy in her hiding-place, had routed her out, and driven her into the enclosure; but, as he could not bar the gate, he stood guard against the opening, and was barking loudly to awaken the household.

As soon as John appeared upon the scene, Bruce returned to his rug as if nothing had happened.

When Old Sheepy was marched into the barrel the next morning, you ought to have seen Bruce strutting about the basement! If Old Sheepy slackened her pace at all, Bruce would growl; if she didn't mind that, he would bark, and would not stop until he had succeeded in calling the dairy-maid to threaten Old Sheepy with the whip.

Priscilla and John thought these little acts of the dog very wise; but I think a sheep that could tell the days of the week, as this one was able to do, and knew enough to run away the night before her turn came, was just as wise as the dog.

The family were loud in their praise of Bruce, however, and, as a reward for his shrewdness, talked of relieving him from further work as soon as they could succeed in training another sheep.

I left the farm-house before this took place: so I cannot say how Bruce bore his laurels. But, if I had had my way, I would have rewarded Old Sheepy too.

"You have been saving up your money for some time," said her mother. "For what have you been saving it?"

"To buy one of those beautiful dolls that can walk without being touched: I do so long to have one!" said the little girl. "But why do you ask, mamma?"

"It was only a passing thought," said mamma.

"But I want to know your passing thought," said Elfrida.

"Well, dear, I thought that one-quarter of the money you will have to pay for a doll would buy you a nice English-German dictionary, by help of which you could learn to read those stories in 'The Nursery.'"

"Let me buy it at once, mamma!" cried Elfrida. "Dolls are nice; but I would rather have a dictionary. May I not go to the bookstore, and buy the book now?"

"Yes, dear: your choice is a wise one. You may go."

Elfrida ran up stairs, put on her cape and bonnet, ran out to the bookstore, and bought the book.

It was hard at first to find out the meaning of some of the words. But the stories were simple, and some of the words were so like the same words in German, that she did not have to look them out.

One day she came running home from school, and said, "O mamma! a little American girl named Clara now comes to our school. She says she will teach me to read."

The little American girl kept her promise. First she[93] would give Elfrida a lesson in English, and then Elfrida would give her a lesson in German. And so they both grew to be nice little scholars. Elfrida would talk to Clara in English, and Clara would answer her in German. Soon they could each talk both languages quite well.

His aunt laughed at him too, sometimes. She was rather[94] a queer aunt, and not at all like the aunts we read of in story-books. But his father was just the best father that anybody ever heard of.

They lived in Sunland, a little town not many miles from Boston; and every morning Parley-voo would hurry down to give his father a kiss before he went away to his business in the city. Then, when the train went by, he would stand at the window, and wave his little white handkerchief, and then his father would wave back at him, as if to say, "Good-by, once more, my dear little Parley-voo, good-by!"

But one morning he was so very sleepy, that he could not open his eyes when his nurse told him it was time to get up. He called the nurse a bonne, as they do in Paris. He pushed her away, and went to sleep again, and the first thing he heard was the train going by with a "choo, choo, choo," and his father was gone without a kiss.

Then Parley-voo cried, and said it was his bonne's fault. He went to the window, and there he stood crying. He could not eat the nice breakfast that his nurse brought him, and would not let her dress him. So she went away, and shut the door, and left him to dress himself.

In his hurry he put on one red stocking and one blue one. His little kilt suit hung so high up in the closet, that he could not reach it: so he drew on an old faded dress a good deal too short, and it made him look just like a girl.

In this rig he went down stairs, and his aunt laughed so that she almost cried when she saw him. That made him feel worse than ever, and he grew worse than ever. I am sorry to tell it; but he flew at her, and kicked her. His mother could not stop him, and his aunt had to run away.

But before long Parley-voo began to be sorry; for he was not a bad child, only thoughtless and wilful. And when his mother whispered to him to go and tell his aunt how sorry[95] he was, the little red and blue legs flew across the room, and up the stairs to find his aunt.

She sat in her room at her small table, and was taking a cup of tea. She did not look up when she heard him coming, and he hardly dared to go in. But he had a brave little heart; and calling out, "Aunty, I'm sorry," he ran up to her, and clasping her neck with his little loving arms, "I am very sorry, aunty," he said again. And they made it all up.

His aunt told him that she thought it would be a good plan to write to his papa, and tell him how it happened that his little boy was too late to kiss him good-by. Then she took out of her desk a sheet of paper; and Parley-voo, with his aunt's help, printed this letter:—

Dear Papa,—I did not see you, and I cried. Did you wave to me? I said it was the bonne's fault, and I dressed myself. Aunt Tib laughed. I kicked her. I'm sorry. I sha'n't do it any more. Mamma sends love and three kisses. So do I. Aunt Tib sends her love too.

After this, Parley-voo and his aunt Tib were the best of friends. It was a long time before he was too late again to say good-by to his father, or had any trouble with his bonne.

Transcriber's Notes: Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The original text for the January issue had a table of contents that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the January issue had a title page. This page was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number added on the title page after the Volume number.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Nursery, March 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, MARCH 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

***** This file should be named 40754-h.htm or 40754-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/0/7/5/40754/

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.