"I'm sure I don't know!"

"Don't tell anybody!"

"Oh, no! oh, no!"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Nursery, April 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Nursery, April 1881, Vol. XXIX

A Monthly Magazine for Youngest Readers

Author: Various

Release Date: September 14, 2012 [EBook #40755]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, APRIL 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

| PAGE | |

| Lucy | 97 |

| The Savoyard | 100 |

| A Bear's Story | 102 |

| Take Care | 108 |

| Letter from China | 109 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 113 |

| The Bird who has no Nest | 114 |

| A Shrine | 115 |

| Susie's Dancing-Lesson | 117 |

| The Deserted House | 122 |

| Dame Trott and her Son | 124 |

| Bossy's Fright | 125 |

| PAGE | |

| A Merry Go-round | 99 |

| Secrets | 105 |

| Going to School | 106 |

| Kings and Queens | 110 |

| Good-Night | 116 |

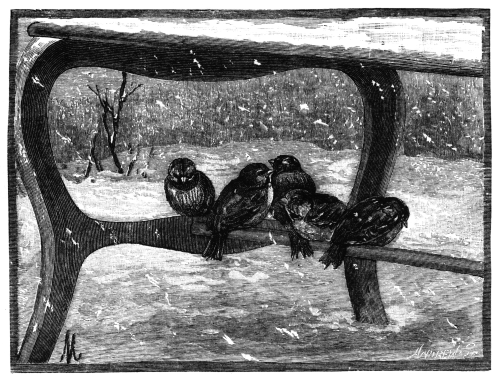

| Five Little Sparrows | 119 |

| Dobbin's Complaint | 121 |

| Tommy Tucker | 123 |

| A Bluebird's Song | 127 |

| The Bird's Return (with music) | 128 |

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 4.

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 4.

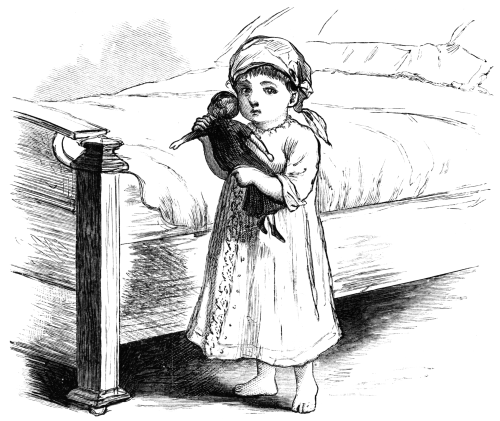

You would not suppose that such a little tot could be left to herself a great while. But often, when she is tired of running about, her mother seats her in the great arm-chair, and there, with her doll in her arms, she sits and amuses herself for hours.

Jip the dog is very fond of Lucy, and very jealous of the doll. If he comes in and sees Lucy and her doll in the arm-chair, he begins to whine.

Then Lucy says in her baby-way (for she cannot yet talk plain), "Come here, Jip!"

Jip jumps up into the chair. Lucy puts her arm round him and pats him fondly. Jip looks up in her face, as much as to say, "Don't you love me, Lucy? Am I not as good as the doll? Why don't you pat me?"

Lucy knows what he means just as well as if he said it in words. "Yes, Jip, you good little dog, I do love you," she says, "and Dolly loves you too. You will take good care of us; won't you, Jip?"

And Jip seems to know what Lucy says; for he answers by another loving look, "Yes, Lucy, I will take care of you. Nobody shall harm you while I am here. I will be your watch-dog. But don't forget to pet me as well as your doll. I like to be petted."

Then Lucy pats him, and says, "Good little Jip, I will never forget you!" That makes him happy; and so they are both happy together.

Savoy is in the eastern part of France, just south of the Lake of Geneva. You will easily find it on the map. It is a fertile country, but there are many poor people there who live chiefly upon chestnuts and potatoes.

Though fond of their birthplace, many of them leave it during the winters, and go to Italy, Spain, and other parts of France in search of work.

Carl, the boy in the picture, is one of this class. His[101] parents are too poor to support him, and he is sent out to seek his own living; but he is not a beggar. He earns something by raising guinea-pigs, which he sells to boys and girls for pets. He carries them, as you see, in a box slung from his neck. But they are so tame that he takes them out and lets them run up on his shoulders.

The guinea-pig, when full-grown, is not much bigger than[102] a large rat. In shape it is a good deal like a fat pig. When hungry it grunts like a pig. In color it is white, spotted with orange and black. It is a native of Brazil.

Guinea-pigs serve very well for pets. Some children are very fond of them. But old folks like me prefer pets of another sort.

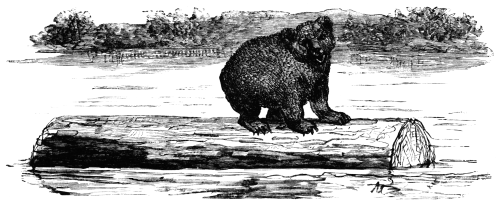

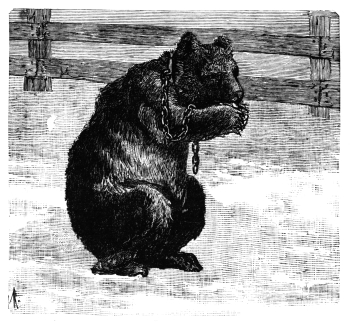

I was a careless young cub, and one day, when at play on the river-side, I went too near the steep bank, fell over it, and went down splash into the water. It was very deep, and there was a strong current. I had never been taught to swim. I was in such a fright that I could not even cry for help.

The water was choking me, and I was nearly drowned,[103] when a kind log came floating by to my rescue. It seemed like a friend sent from home. I scrambled to the top of it, bade good-by to my sister, who stood crying on the bank, and went drifting down the river.

Before long two queer-looking objects came toward me, paddling along in a sort of hollow log. Seeing plainly that they were not bears, I felt much afraid of them. My mother had often talked to me about some fierce creatures called "men," and had told me always to keep out of their way.

I felt sure that these were men; but how could I get out of their way when I was adrift on a log? They came right down upon me, and there I sat, whining and crying and trembling. "What were these dreadful men made for?" thought I. "Why can they not leave us poor bears in peace?"

I fully expected to be killed. But, instead of killing me, one of the men took me in his arms, and held me till we came to the shore. Then I wanted to go back to my mother, and I tried to get away. But he held me all the tighter, and after a while he tied my feet together. I could do nothing but cry, and at last I cried myself to sleep.[104]

When I awoke I found myself in this town, called "Big Rapids," and here I have been ever since. It seemed to me very strange at first not to be in the woods, but in the midst of queer-looking white objects called "houses."

I started to take a walk, hoping to fall in with some bear of my acquaintance; but a hard thing fastened to my neck held me back. It is what men call a "chain," as I have since learned, and it compels me to stay in one place all the time.

I am no longer a cub, but am a full-grown bear. This kind of life does not suit me very well, but I have got used to it. One can get used to almost any thing. I have even got used to the society of men and women.

Their cubs (called boys and girls) often play with me, and sometimes they tease me. Once, when a boy was teasing me, I gave him a scare which will be apt to teach him better manners. I will tell you how it was.

The boy held out an apple, and, just as I was about to take it, he pulled it away. This mean trick he played three[105] times. He tried it once more, and then I gave such a spring that my chain broke.

The boy dropped his apple, and ran. You ought to have seen that boy run! He didn't dare even to look back. But, if he had looked back, he would have seen me munching his apple with great relish.

I didn't want to hurt a cub like him; but some bears that I know wouldn't have been so for-bear-ing.

Young Tom mounts his old horse and takes a ride. He sits up like a bold dragoon. The horse is not a gay one. He will not shy. He will not run away. But he has one fault: he may take it into his head to roll. Tom must take care.

Young Bob climbs a rope hand over hand. He holds on tight, and climbs up quite high. He is a bold boy. It is a good plan to climb. But take care, or you may fall. Do not let go with one hand till you get hold with the other.

There are four boys and three girls. The two youngest boys, Dwight and Louis, are twins. They are the emperors.

Their reign began nearly three years ago. Master Ted, the next elder brother, who was then emperor, had to give way to them, and very sweetly he did it. It was hard for him to see his dear old Chinese nurse transfer her love and care to any one else; and even now, when he hears her call one of the emperors her "little pet," he says to her, "But you know you have a big pet too."

Thus far the twin-emperors have had none but loyal subjects;[110] but, as they grow out of their babyhood, there are signs of rebellion. The three sisters rebel because Emperors Dwight and Louis will not let them practise their music-lessons in peace. Ted says, "Do find me a place where I can pound nails alone;" for the emperors will insist upon helping him.

The emperors have already learned to walk, though they talk only in a language of their own. When they begin to talk plainly in the language of their subjects, I fear that their reign will come to an end.

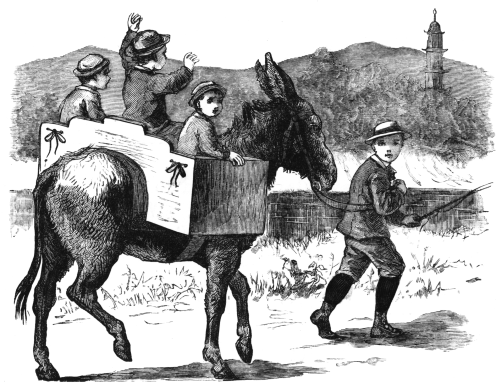

The picture shows you how ten-year-old brother Ned takes his three little brothers to ride on his donkey.

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

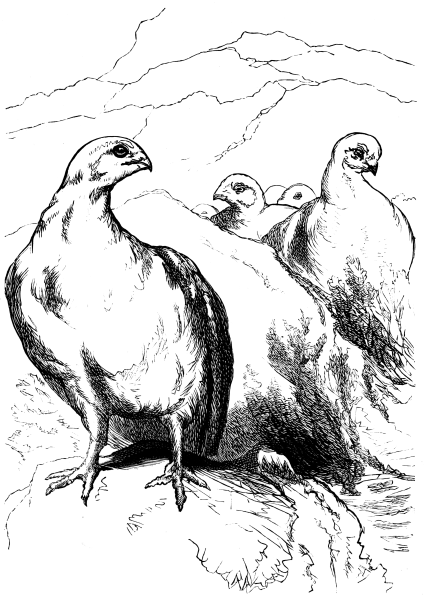

There are some birds that can take care of themselves almost as soon as they are born; but Mrs. Cuckoo never leaves her eggs in their nests. Oh, no! she chooses a nest in which the young birds are well cared for by their mothers, and fed with food on which the young cuckoos thrive best.

Why she is too idle to build her own nest, no one knows. Some people say it is because she stays so short a time in the same country, that her young ones would not get strong enough to fly away with her, if she waited to build her nest. Others think it is because she is such a great eater, that she cannot spend time to find food for her children.

But the kind foster-mothers, the larks and the thrushes, care for the egg that the cuckoo leaves in their houses, although, if any other bird leaves one, they will take no care of it at all, but roll it out upon the ground.

The Scotch word for cuckoo, gowk, means, also, a foolish person. But I think they ought rather to have named it a wicked person; for the young cuckoo is so ungrateful and selfish, that he often gets one of the other little birds on his back, and then, climbing to the top of the nest, throws it over the edge. These are the English cuckoos of which I have been telling you. I am glad to say that their American cousins take care of their own children.

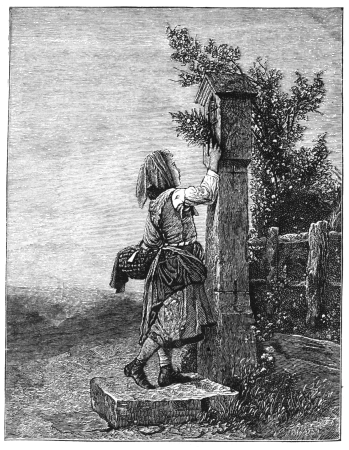

This box is attached to a stone pillar or other fixed monument, and thus marks a place at which the pious Catholics kneel to offer up their prayers.

In Italy and Spain shrines are very common, not only in the churches, but at the roadsides. The picture shows us[116] one with a little girl holding a bunch of flowers in front of the sacred image which she sees in it.

In this country they are to be seen only in churches; but we often speak of any hallowed place as a shrine.

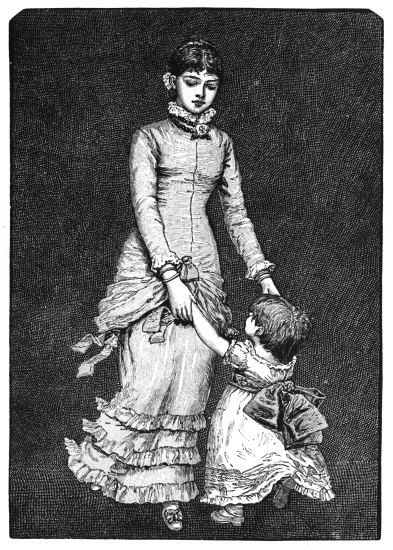

Thus Ann will say, "What is the matter, Susie? Are[118] you hungry? No. Are you sleepy? Not a bit of it. Do you want me to tell you a story? No. Are you tired? No. I have it: you want a good dose of exercise. That is the very thing you need. Come here now, and I'll give you a dancing-lesson."

She takes Susie's hands, and whirls her out on the floor[119] before she has time to say a word. Then Ann begins to sing,—

"What!" says Ann. "Haven't you had dancing enough? Well, then, how would you like a fancy dance? Mind your steps now. Do as you see me do. Keep time with the music.

So the little girl is danced about until she has to stop to take breath; and by that time she is so full of fun, that there is no room for a frown on her pretty face.

To-day I called again. All was still. Not a voice did I hear. The roofless house was filled with snow. The walls looked dark and sad. The leaves that once cast lovely shadows about them were gone.

As I stood looking at the empty house, Ethel, who is very young but very wise, exclaimed, "The family have gone south for the winter, but are sure to come back in the spring. There will be gay times here pretty soon."

Just then a sharp gust of wind came, and the old house shook as if about to fall. Ethel stood ready to catch it.

What, a child catch a falling house, as if it were a baseball! What if the timbers should strike her? Ah! but this house was a very light building. Snow and all, it was not much heavier than a handful of roses.

Now you know what I mean. Vine Street runs from the floor to the top of the piazza. The swallow homestead is[123] just at the head of that street. The timbers are sticks and straw. The roof is the sky. And, as to the happy little family of Mr. and Mrs. Swallow, if you come here in the month of May, I will show them to you in their home.

In this little house lives good Dame Trott, who keeps eggs and milk for sale. She has two cows and a flock of hens. Her son John helps her to take care of them. He is a very good boy. |

|

| John is just ten years old. He goes to school. When the school is done for the day, he goes out to the field to drive home the cows. Here you may see him on a fence at the end of the lane. He wears a queer sort of frock.

D. E. F. |

Some check had to be put upon her. So one day she[126] went to the pasture with her head tied down to her foot by a strong rope. In about three hours a man came running up to the house, to tell us that old Bossy had fallen over a log, and was lying on her back.

Now, if a cow gets down on her back, in this way, in a place where she cannot turn over, she is in great danger. It is called being "cast." This man said, "Come quickly, for old Bossy is cast." Every one ran to the pasture, and by much pulling and lifting got the cow up. She looked very happy to be on her feet once more; but as soon as the rope was cut she was at her old tricks again.

The very next day she was found quietly eating down a neighbor's corn. Something must be done. We did not like to tie her head down again: so we concluded to put a board over her eyes.

The board was brought, and fastened with cords to her horns. She stopped chewing her cud at once and stood still. The men left her in the lane that led to the pasture, and went to their work. She did not move. I don't think she even whisked her tail to drive away the flies.

When the men came home to dinner, they were surprised to see her still standing in the very place where they left her. They patted her kindly, took the board off, and saw on her forehead a spot as large as a man's hand, where the hair had turned grayish-white. There was not a bit of white on her forehead before the board was put on. The poor thing had begun to turn gray from sheer fright.

We all felt sorry for her; and the board was never again tied to her horns. After a time she began to chew her cud, and seemed all right; and she went on pushing down the fences, and opening the gates, just as often as before. This is a true story.

| There's a glad merry voice, children, calling to you, A gay burst of song from a wee bit of blue, Poised daintily there on the maple-twig now, Like a bright little blossom upon the bare bough,— "Tu-ra-la, tu-ra-lee, We're coming, you see: I'm building my nest in the old apple-tree. "To you, little children, this message I bring, The birds, every one, will return with the spring. What care I if cold winds are blowing around! The flowers are already awake under ground. Tu-ra-la, tu-ra-lee: If snowflakes I see, I'll dream they are blooms shaken off from the tree. "Hark! the shy little brooklet is humming a song As it breaks loose from winter, and dances along. How happy we'll be through the blithe summer hours,— The children, the sunbeams, the birds, and the flowers! Tu-ra-la, tu-ra-lee: How busy we'll be, My sweet mate and I, in the old apple-tree!" RUTH REVERE. |

Transcriber's Notes: Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The original text for the January issue had a table of contents that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the January issue had a title page. This page was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number added on the title page after the Volume number.

Page 106, the final line of the first stanza of "Going to School" was indented to follow the pattern of the remaining stanzas.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Nursery, April 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, APRIL 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

***** This file should be named 40755-h.htm or 40755-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/0/7/5/40755/

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.