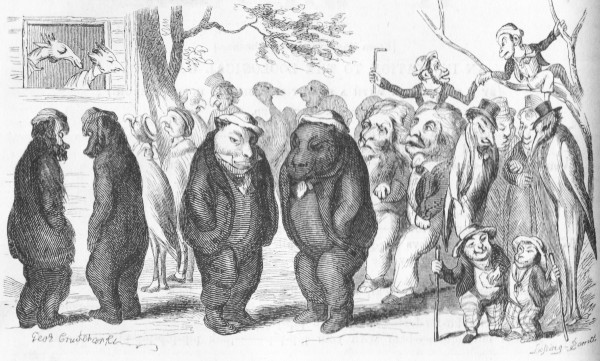

FELLOWS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY.

FELLOWS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY.

On the 5th of July, 1789, Howard quitted England to return no more. Arriving at Amsterdam on the 7th, he proceeded by slow stages through Germany and Prussia into the empire of the Czar, which he entered at Riga. He was destined never more to quit the soil of Russia. The tremendous destruction of human life to which the military system of that country gives rise, had not then, as it has since, become a recognized fact in Western Europe; and the unconceived and inconceivable miseries to which Howard found recruits and soldiers exposed in Moscow, induced him to devote his attention to them and to their cause. In these investigations horrors turned up of which he had never dreamed, and impressed him still more profoundly with a sense of the hollowness of the Russian pretense of civilization. In the forced marches of recruits to the armies over horrid roads, being ill-clothed and worse fed, he found that thousands fell sick by the way, dropped at the roadside, and were either left there to die of starvation, or transferred to miserable hospitals, where fever soon finished what fatigue had begun. This waste of life was quite systematic. An hospital for the reception of the poor wretches had recently been erected at Krementschuk, a town on the Dnieper, which contained at that time 400 patients in its unwholesome wards. Thither Howard repaired to prosecute his new inquiries. The rooms he found much too full; many of the soldiers were dreadfully ill of the scurvy, yet they were all dieted alike, on sour bread and still sourer quas, alternated with a sort of water-gruel, which, if not eaten one day, was served up again the next. From this place, Howard went down the Dnieper to Cherson, where he examined all the prisons and hospitals, and made various excursions in the neighborhood for the same purpose. The hospitals were worthy of the evil which they were designed to alleviate. Our countryman thus sums up his observations upon them: "The primary objects in all hospitals seem here neglected—namely, cleanliness, air, diet, separation, and attention. These are such essentials, that humanity and good policy equally demand that no expense should be spared to procure them. Care in this respect, I am persuaded, would save many more lives than the parade of medicines in the adjoining apothecary's shop."

While at Cherson, Howard had the profound gratification of reading in the public prints of the capture and fall of the Bastille; and he talked with delight of visiting its ruins and moralizing upon its site, should he be again spared to return to the West. But, however moved by that great event, so important for all Europe, he did not allow it to divert him from his own more especial work; the sufferings of poor Russian soldiers in the hospitals of Cherson, Witowka, and St. Nicholas, had higher claim upon his notice at that moment, than even the great Revolution making in the Faubourg St. Antoine at Paris.

The reader will recall to mind, that, at the time of Howard's residence at Cherson, a desperate war was raging between the Sultan and the Autocrat. The strong fortress of Bender had just fallen into the power of Russia, but as the winter was already too far advanced to allow the army to push forward until spring, the commander of the imperial forces gave permission to such of his officers as chose to go and spend the Christmas with their friends in Cherson. That city was consequently crowded with rank and fashion. All the city was in high spirits. The victories of the imperial troops produced a general state of jubilation. Rejoicing was the order of the day, and dancing and revelry the business of the night. But in the midst of these festivities, a virulent and infectious fever broke out—brought, as Howard believed, by the military from the camp. One of the sufferers from this disorder was a young lady who resided about twenty-four miles from Cherson, but who had been a constant attendant at the recent balls and routs. Her fever very soon assumed an alarming form; and as a last resource her friends waited upon Howard—whose reputation as a leech was still on the increase—and implored him to ride over and see her. At first he refused, on the ground that he was only a physician to the poor; but their importunities increasing, and reports arriving that she was getting worse and worse, he at length acceded to their wish—being also pressed thereto by his intimate friend, Admiral Mordvinoff, chief admiral of the Black Sea fleet—and went with them. He prescribed for the lady's case; and then, leaving word that if she improved they must send to him again, but if she did not, it would be useless, went to make some visits to the sick of an hospital in the neighborhood. The lady gradually improved under the change of treatment, and in a day or two a letter was written to Howard to acquaint him with the circumstance, and requesting him to come again without delay. Very unfortunately this letter miscarried, and was not delivered for eight days—when it was brought to him at Mordvinoff's house. When he noticed the date, Howard was greatly alarmed—for he had become interested in the case of his fair patient, and thought himself in a manner responsible for any mishap which might have befallen her. Although, when the note came to hand, it was a cold, wintry, tempestuous night, with the rain falling in torrents, he did not hesitate for a moment about setting off for her residence. Unfortunately, again, no post-horses could be had at the time; and he was compelled to mount a dray-horse used in the admiral's family for carrying water, whose slow pace protracted the journey until he was saturated with wet and benumbed with cold. He arrived, too, to find his patient dying; yet, not willing to see her expire without a struggle to save her, he administered some medicines to excite perspiration, and remained for some hours at her side to watch the first signs of the effect produced. After a time, he thought the dose was beginning to operate, and, wishing to avoid exposing her to the chance of a fresh cold by uncovering her arms, placed his hand under the coverlet to feel her pulse. On raising it up a little, a most offensive smell escaped from beneath the clothes, and Howard always thought the infection was then communicated to him. Next day she died.

For a day or two, Howard remained unconscious of his danger; feeling only a slight indisposition, easily accounted for by his recent exertions; which he nevertheless so far humored as to keep within doors; until, finding himself one day rather better than usual, he went out to dine with Admiral Mordvinoff. There was a large animated party present, and he staid later than was usual with him. On reaching his lodgings he felt unwell, and fancied he was about to have an attack of gout. Taking a dose of sal volatile in a little tea, he went to bed. About four in the morning he awoke, and feeling no better, took another dose. During the day he grew worse, and found himself unable to take his customary exercise; toward night a violent fever seized him, and he had recourse to a favorite medicine of that period, called "James's Powders." On the 12th of January, he fell down suddenly in a fit—his face was flushed and black, his breathing difficult, his eyes closed firmly, and he remained quite insensible for half an hour. From that day he became weaker and weaker; though few even then suspected that his end was near. Acting as his own physician, he continued at intervals to take his favorite powders; notwithstanding which his friends at Cherson—for he was universally loved and respected in that city, though his residence had been so short—soon surrounded him with the highest medical skill which the province supplied. As soon as his illness became known, Prince Potemkin, the princely and unprincipled favorite of Catherine, then resident in Cherson, sent his own physician to attend him; and no effort was spared to preserve a life so valuable to the world. Still he went worse and worse.

On the 17th, that alarming fit recurred; and although, as on the former occasion, the state of complete insensibility lasted only a short time, it evidently affected his brain—and from that moment the gravity of his peril was understood by himself, if not by those about him.[Pg 300] On the 8th, he went worse rapidly. A violent hiccuping came on, attended with considerable pain, which continued until the middle of the following day, when it was allayed by means of copious musk drafts.

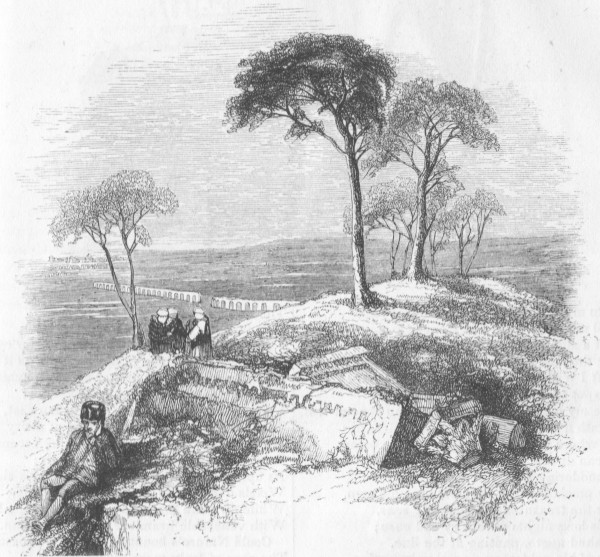

Early on the morning of the 20th, came to see him his most intimate friend, Admiral Priestman—a Russianized Englishman in the service of the empress. During his sojourn at Cherson, Howard had been in the habit of almost daily intercourse with his gallant ex-countryman. When taken ill, not himself considering it at first serious, no notice of it had been sent out; but not seeing his friend for several days, Priestman began to feel uneasy, and went off to his lodgings to learn the cause. He found Howard sitting at a small stove in his bedroom—the winter was excessively severe—and very weak and low. The admiral thought him merely laboring under a temporary depression of spirits, and by lively, rattling conversation endeavored to rouse him from his torpidity. But Howard was fully conscious that death was nigh. He knew now that he was not to die in Egypt; and, in spite of his friend's cheerfulness, his mind still reverted to the solemn thought of his approaching end. Priestman told him not to give way to such gloomy fancies, and they would soon leave him. "Priestman," said Howard, in his mild and serious voice, "you style this a dull conversation, and endeavor to divert my mind from dwelling on the thought of death; but I entertain very different sentiments. Death has no terrors for me; it is an event I always look to with cheerfulness, if not with pleasure; and be assured, the subject is more grateful to me than any other." And then he went on to say—"I am well aware that I have but a short time to live; my mode of life has rendered it impossible that I should get rid of this fever. If I had lived as you do, eating heartily of animal food and drinking wine, I might, perhaps, by altering my diet, have been able to subdue it. But how can such a man as I am lower his diet, who has been accustomed for years to live upon vegetables and water, a little bread and a little tea? I have no method of lowering my nourishment—and therefore I must die;" and then turning to his friend, added, smiling—"It is only such jolly fellows as you, Priestman, who get over these fevers." This melancholy pleasantry was more than the gallant sailor could bear; he turned away to conceal his emotion; his heart was full, and he remained silent, while Howard, with no despondency in his tone, but with a calm and settled serenity of manner, as if the death-pangs were already past, went on to speak of his end, and of his wishes as to his funeral. "There is a spot," said he, "near the village of Dauphiney—this would suit me nicely; you know it well, for I have often said that I should like to be buried there; and let me beg of you, as you value your old friend, not to suffer any pomp to be used at my funeral; nor let any monument nor monumental inscription whatsoever be made to mark where I am laid; but lay me quietly in the earth, place a sun-dial over my grave, and let me be forgotten."

In this strain of true Christian philosophy did Howard speak of his exit from a world in which he felt that he had done his work. The ground in which he had selected to fix his everlasting rest, situated about two miles from Cherson, on the edge of the great highway to St. Nicholas, belonged to a French gentleman who had treated him with distinguished attention and kindness during his stay in the vicinity; and, having made his choice, he was very anxious to know whether permission could be obtained for the purpose, and begged his gallant friend to set off immediately and ascertain that for him. Priestman was not very willing to leave his friend at such a time and on such a gloomy errand; he fancied people would think him crazy in asking permission to make a grave for a man still alive, and whom few as yet knew to be ill; but the earnestness of the dying martyr at length overcame his reluctance, and he set forth.

Scarcely had he departed on his strange mission, when a letter arrived from England, written by a gentleman who had just been down to Leicester to see young Howard, giving a highly favorable account of the progress of his recovery, and expressing a belief that, when the philanthropist returned to his native land, he would find his son greatly improved. This intelligence came to the deathbed of the pious Christian like a ray of light from heaven. His eye brightened; a heavy load seemed lifted from his heart; and he spoke of his child with the tenderness and affection of a mother. He called Thomasson to his bedside, and bade him tell his son, when he went home, how long and how fervently he had prayed for his recovery, and especially during this last illness.

Toward evening, Admiral Priestman returned from a successful application; with this result Howard appeared highly gratified, and soon after his arrival retired to rest. Priestman, conscious now of the imminency of the danger, would leave him alone no more, but resolutely remained, and sat at the bedside. Although still sensible, Howard had now become too weak to converse. After a long silence, during which he seemed lost in profound meditation, he recovered for a moment his presence of mind, and taking the letter which had just before come to hand—evidently the subject of his thoughts—out of his bosom, he gave it to the admiral to read; and when the latter had glanced it through, said tenderly: "Is not this comfort for a dying father?" These were almost the last words he uttered. Soon after, he fell into a state of unconsciousness, the calm of sleep, of an unbroken rest—but even then the insensibility was more apparent than real, for on Admiral Mordvinoff, who arrived just in time to see the last of his illustrious friend, asking permission to send for a certain doctor, in whom he had great faith, the patient gave a sign which implied consent; but before this person[Pg 301] could arrive he had fallen off. Howard was dead!

This mournful event took place about eight o'clock on the morning of the 20th of January, 1790—1500 miles from his native land, with only strangers round about his bed; strangers, not to his heart, though their acquaintance with his virtues had been brief—but to his race, his language, and his creed. He, however, who was the friend of all—the citizen of the world, in its highest sense—found friends in all. Never perhaps had mortal man such funeral honors. Never before, perhaps, had a human being existed in whose demise so universal an interest could be felt. His death fell on the mind of Europe like an ominous shadow; the melancholy wail of grief which arose on the Dnieper, was echoed from the Thames, and soon re-echoed from the Tagus, and the Neva, and the Dardanelles. Every where Howard had friends—more than could be thought till death cut off restraint, and threw the flood-gates of sympathy wide open. Then the affluent tide rolled in like the dawn of a summer day. Cherson went into deep mourning for the illustrious stranger; and there was hardly a person in the province who was not greatly affected on learning that he had chosen to fix his final resting-place on the Russian soil. In defiance of his own wishes on the subject, the enthusiasm of the people improvised a public funeral. The Prince of Moldavia, Admirals Priestman and Mordvinoff, all the generals and staff officers of the garrison, the whole body of the magistrates and merchants of the province, and a large party of cavalry, accompanied by an immense cavalcade of private persons, formed the funeral procession. Nor was the grief by any means confined to the higher orders. In the wake of the more stately band of mourners, followed on foot a concourse of at least three thousand persons—slaves, prisoners, sailors, soldiers, peasants—men whose best and most devoted friend the hero of these martial honors had ever been; and from this after, humbler train of followers, arose the truest, tenderest expression of respect and sorrow for the dead. When the funeral pomp was over, the remains of their benefactor lowered into the earth, and the proud procession of the great had moved away, then would these simple children of the soil steal noiselessly to the edge of the deep grave, and, with their hearts full of grief, whisper in low voices to each other of all that they had seen and known of the good stranger's acts of charity and kindness. Good indeed he had been to them. Little used to acts or words of love from their own lords, they had felt the power of his mild manner, his tender devotion to them, only the more deeply from its novelty. To them, how irreparable the loss! The higher ranks had lost the grace of a benignant presence in their high circle; but they—the poor, the friendless—had lost in him their friend—almost their father. Nature is ever true; they felt how much that grave had robbed them of. Not a dry eye was seen among them; and looking sadly down into the hole where all that now remained of their physician lay, they marveled much why he, a stranger to them, had left his home, and his friends, and country, to become the unpaid servant of the poor in a land so far away; and not knowing how, in their simple hearts, to account for this, they silently dropped their tears into his grave, and slowly moved away—wondering at all that they had seen and known of him who was now dead, and thinking sadly of the long, long time ere they might find another friend like him.

The hole was then filled up—and what had once been Howard was seen of man no more. A small pyramid was raised above the spot, instead of the sun-dial which he had himself suggested; and the casual traveler in Prussian Tartary is still attracted to the place as to one of the holiest shrines of which this earth can boast.

Words can not depict the profound sensation which the arrival of this mournful news produced in England. The death-shaft cut the withes which had kept his reputation down. All at once the nation awoke to a full consciousness of his colossal fame and his transcendent virtues. Howard was now—history. Envy and jealousy were past: rivalry had ended on the brink of the grave. Death alone sets a man on fair terms with society. The death of a great man is always a calamity; but it is only when a country loses one of its illustrious children in a distant land, and under peculiar circumstances, that the full measure of the national calamity is felt. They who can recollect the wild and deep sensation of pity and regret which the arrival of the news of Byron's death at Missolonghi produced in England, can alone conceive of any thing like the state of the public mind on the first announcement of the close of a career still more useful and more glorious. Every possible mark of honor—public and private—was paid to the memory of Howard. All orders of men vied with each other in heaping honors upon his name. The court, the press, parliament, the bar, the pulpit, and the stage—each in its different fashion—paid the well-earned tribute of respect. The intelligence of his demise was publicly announced in the official Gazette—a distinction never before accorded to a private individual. The muses sang his virtues with innumerable voices; the churches echoed with his praise; the senate and the judgment-seat resounded with the tribute to his merits; and even at the theatres, his character was exhibited in imaginary scenes, and a monody on his death was delivered from the foot lights.

Nor was a more enduring memorial wanting. The long dormant Committee of the Howardian fund was resuscitated, and the sculptor Bacon was employed to make a full length marble statue of the Philanthropist. At that time it was in contemplation to make St. Paul's serve the double purpose of a cathedral and a Walhalla; and this design was inaugurated by placing there, as the first great worthy of England,[Pg 302] the statue of John Howard. It stands immediately on the right hand of the choir-screen; it is a handsome figure, tolerably faithful, and is illustrated by emblems of his noble deeds, and by the following inscription: "This extraordinary man had the fortune to be honored, while living, in the manner which his virtues deserved; he received the thanks of both houses of the British and Irish Parliaments, for his eminent services rendered to his country and to mankind. Our national prisons and hospitals, improved upon the suggestion of his wisdom, bear testimony to the solidity of his judgment, and to the estimation in which he was held. In every part of the civilized world, which he traversed to reduce the sum of human misery—from the throne to the dungeon—his name was mentioned with respect, gratitude, and admiration. His modesty alone defeated various efforts that were made during his life to erect this statue, which the public has now consecrated to his memory. He was born at Hackney, in the county of Middlesex, September 2, 1726. The early part of his life he spent in retirement, residing principally upon his paternal estate at Cardington, in Bedfordshire; for which county he served the office of sheriff in the year 1763. He expired at Cherson, in Russian Tartary, on the 20th of January, 1790, a victim to the perilous and benevolent attempt to ascertain the cause of, and find an efficacious remedy for the plague. He trod an open but unfrequented path to immortality in the ardent but unintermitted exercise of Christian charity: may this tribute to his fame excite an emulation of his truly glorious achievements!"

(Continued from page 165.)

Once having begun, it followed naturally that the war should deepen in bitterness. Wounds that wrote memorials in the flesh, insults that rankled in the heart—these were not features of the case likely to be forgotten by our enemies, and far less by my fiery brother. I, for my part, entered not into any of the passions that war may be supposed to kindle, except only the chronic passion of anxiety. Fear it was not; for experience had taught me that, under the random firing of our undisciplined enemies, the chances were not many of being wounded; but the uncertainties that beset every conflict, as regarded my power to maintain the requisite connection with my brother, and the absolute darkness that brooded over that last worst contingency—the case of being captured, and carried off to Gath as a trophy won from Israel—these were penalties attached to the war that ran too violently into the current of my constitutional despondency, ever to give way under any casual elation of success. Success we really had at times—often in skirmishes; and once, at least, as the reader will find to his mortification, if he is wicked enough to take the side of the Philistines, a most smashing victory in a pitched battle. But even then, and while the hurrahs were yet ascending from our jubilating lips, the freezing memento came back to my heart of that deadly depression which, duly at the coming round of the morning and evening watches, traveled with me like my shadow on our approach to the memorable bridge. A bridge of sighs[2] too surely it was for me; and even for my brother it formed an object of fierce yet anxious jealousy, that he could not always disguise, as we first came in sight of it: for, if it happened to be occupied in strength, there was an end of all hope that we could attempt the passage; and that was a fortunate solution of the affair, as it imposed no evil beyond a circuit; which, at least, enjoyed the blessing of peace, although the sarcastic public might choose to call it inglorious. Even this shade of ignominy, however, my brother contrived to color favorably, by calling us—that is, me and himself—"a corps of observation;" and he condescendingly explained to me, that although making "a lateral movement," he had his eye upon the enemy, and "might yet come round upon his left flank in a way that wouldn't perhaps prove very agreeable." This, from the nature of the ground, never happened. We crossed the river out of sight from the enemy's position; and my brother's vengeance, being reserved until he came round into the rear of Philistia, from which a good retreat was always open to Greenhay; naturally discharged itself in triple deluges of stones. On this line of policy there was, therefore, no cause for anxiety; but the common case was, that the numbers might not be such as to justify this caution, and yet quite enough for mischief. For my brother, however, stung and carried headlong into hostility by the martial instincts of his nature, the uneasiness of doubt or insecurity was swallowed up by his joy in the anticipation of victory, or even of contest; while to myself,[Pg 303] whose exultation was purely official and ceremonial, as due by loyalty and legal process from a cadet of the belligerent house, no such compensation existed. The enemy was no enemy in my eyes; his affronts were but retaliations; and his insults were so inapplicable to my unworthy self, being of a calibre exclusively meant for the use of my brother, that from me they recoiled, one and all, as cannon-shot from cotton bags.

This inordinate pugnacity of my brother, this rabid appetite for trials of prowess, had, indeed, forced itself into display on the very first interview I ever had with him. On the night of his return from Louth, an artisan, employed in the decorations of Greenhay, had entered into conversation with him upon the pre-eminence of Lancashire among the provinces of England. According to him, the county of Lancaster (to translate his meaning into Roman phrase) was the prerogative tribe of England. And really I am disposed to think that it still is such, mongrelized as it has long been by Cambrian and Hibernian immigrations. There is not on earth such another focus of burning energy. Among other things, the man had magnified the county as containing (which it then did) by very much the largest remnant of old Roman Catholic families—families that were loyal to the back-bone (in those days a crowning honor); that were of the ancient faith, and of the most ancient English blood; none of your upstart, dissenting terræ filii, but men that might have shaken hands with Cœur de Lion, or at least come of ancestors that had. "And, in short, young gentleman," he concluded, "the whole county, not this part, or that part, but take it as you find it, north and south, is a very tall county."

What it was exactly that he meant by tall, I can not say. From the intense predominance in Lancashire of old genuine mother English, it is probable that he meant stout-hearted, for that was the old acceptation of the word tall, and not (as it is now understood) high in stature. "A tall ship" meant a stout and sea-worthy ship; "a tall man," meant a man that was at once able-bodied and true-hearted. My brother, however, chose to understand it in the ordinary modern sense, and he replied, "Yes, it's tall enough, if you take it south and north: from Bullock Smithy in the south, to beyond Lancaster in the north, it measures a matter of sixty miles or more; certainly it's tall, but then it's very thin, generally speaking."

"Ay, but," said the man, "thick or thin, it's a county palatine."

"Well, I don't care much for that," rejoined my brother; "palatine or not palatine, thick or thin, I wouldn't take any jaw (which meant insolence) from Lancashire, more than from any other shire."

The man stared a little at this unlooked-for attitude of defiance to a county palatine; but, recovering himself, he said, that my brother must take it, if Lancashire chose to offer it.

"But I wouldn't," replied my brother. "Look here: Lincolnshire, the county that I've been staying in for these, I don't know how many years—and a very tall county, too, tall and fat—did I take any jaw from her? Ask the sheriff. And Leicestershire, where I've generally spent my holidays, did I take jaw from her? Tell me that. Neither, again, did Louth ever dream of giving me any of her jaw; then why should I stand it from Lancashire?"

Certainly, why should he? I, who took no part in all this but as a respectful listener, felt that there was much reason in what my brother said. It was true that, having imbibed from my nurses a profound veneration for my native county, I was rather shocked at any posture (though but in a hypothetical case) of defiance to Lancashire; and yet, if three out of four capital L's had been repulsed in some mysterious offense, I felt that it was mere equity to repulse the fourth. But I prepared anxiously to say, on the authority of my last nurse, that Lancashire (I felt sure) was not the county to offer him any "jaw," whatever that might be. Unhappily, in seeking for words, which came very slowly at all times, to express my benevolent meaning, the opportunity passed over for saying any thing at all on the subject; but, though wounded by his squaring at Lancashire, I yet felt considerable respect for a brother who could thus resolutely set his arms a-kimbo against three tall counties, two of them tolerably fat, and one decent market-town.

The ordinary course of our day's warfare was this: between nine and ten in the morning, occurred our first transit, and consequently our earliest opportunity for doing business. But at this time the great sublunary interest of breakfast, which swallowed up all nobler considerations of glory and ambition, occupied the work-people of the factory (or what in the brutal pedantry of this day are termed the "operatives"), so that very seldom any serious business was transacted. Without any formal armistice, the paramount convenience of such an arrangement silently secured its own recognition. Notice there needed none of truce, when the one side yearned for breakfast, and the other for a respite; the groups, therefore, on or about the bridge, if any at all, were loose in their array, and careless. We passed through them rapidly, and, on my part, uneasily; exchanging only a few snarls, but seldom or ever snapping at each other. The tameness was almost shocking of those who in the afternoon would inevitably resume their natural characters of tiger-cats, wolves, and hunting-leopards. Sometimes, however, my brother felt it to be a duty that we should fight in the morning, particularly when any expression of public joy for a victory—bells ringing in the distance, or when a royal birthday, or some traditional commemoration of ancient feuds (such as the 5th of November), irritated his martial propensities. These being religious festivals, seemed to require of us some extra homage, for which we knew not how to find[Pg 304] any natural or significant expression, except through sharp discharges of stones, that being a language older than Hebrew or Sanscrit, and universally intelligible. But excepting these high days of religious solemnity, when a man is called upon to show that he is not a Pagan or a miscreant in the eldest of senses, by thumping, or trying to thump, somebody who is accused or accusable of being heterodox, the great ceremony of breakfast was allowed to sanctify the hour. Some natural growls we uttered, but hushed them soon, regardless (in Mr. Gray's language) "of the sweeping whirlpool's sway, that hushed in grim repose, looked for his evening prey."

That came but too surely. Yes, evening never forgot to come—never for once forgot to call for its prey. Oh! reader, be you sure of that. Pleasures—how often do they forget themselves, forget their duty, forget their engagements, and fail to revolve! But this odious necessity of fighting never missed its road back, or fell asleep, or loitered by the way, more than a bill of exchange, or a tertian fever. Five times a week (Saturday sometimes, and Sunday always, were days of rest) the same scene rehearsed itself in pretty nearly the very same succession of circumstances. Between four and five o'clock, we had crossed the bridge to the safe, or Greenhay side; then we paused, and waited for the enemy. Sooner or later a bell rang, and from the smoky hive issued the hornets that night and day stung incurably my peace of mind. The order and procession of the incidents after this was odiously monotonous. My brother occupied the main high road, precisely at the point where a very gentle rise of the ground attained its summit; for the bridge lay in a slight valley; and the main military position was fifty or eighty yards perhaps above the bridge; then—but having first examined my pockets in order to be sure that my stock of ammunition, stones, fragments of slate, with a reasonable proportion of brickbats, was all correct and ready for action—he detached me about forty yards to the right, my orders being invariable, and liable to no doubts or "quibbling." Detestable in my ears was that word "quibbling," by which, for a thousand years, if the war had happened to last so long, he would have fastened upon me the imputation of meaning, or wishing at least, to do what he called "pettifogulizing"—that is, to plead some little technical quillet, distinction, or verbal demur, in bar of my orders, under some colorable pretense that, according to their literal construction, they really did not admit of being fulfilled, or perhaps that they admitted it too much as being capable of fulfillment in two senses, either of them a practicable sense. Unhappily for me, which told against all that I could ever have pleaded in self-justification, my Christian name was Thomas—an injury for which I never ceased to upbraid secretly my two godfathers and my one godmother; and with some reason: they ought to have seen what mischief they were brewing; since I am satisfied to this hour that, but for that wretched wo-begone name, saturated with a weight of predestined skepticism that would sink a seventy-four with the most credulous of ship's companies on board, my brother never would have called me Thomas à Didymus, which he did sometimes, or Thomas Aquinas, which he did continually. These baptismal sponsors of mine were surely answerable for all the reproaches against me, suggested by my insufferable name. All that I bore for years by reason of these reproaches, I charge against them; and perhaps an action of damages would have lain against them, as parties to a conspiracy against me. For any thing that I knew, the names might have been titles of honor; but my brother took care to explain the qualities, for better and worse, which distinguished them. Thomas à Didymus, it seemed, had exactly my infirmity of doubting and misgiving, which naturally called up further illustrations of that temper from Bunyan—a writer who occupied a place in our childish library, not very far from the "Arabian Nights." Giant Despair, the Slough of Despond, Doubting Castle, mustered strong in the array of rebukes to my weakness; and, above all, Mr. Ready-to-sink, who was my very picture (it seems) or prophetic type. As to Thomas Aquinas, I was informed that he, like myself, was much given to hair-splitting, or cutting moonbeams with razors; in which I think him very right; considering that in the town of Aquino, and about the year 1400, there were no novels worth speaking of, and not even the shadow of an opera; so that, not being employed upon moonbeams, Thomas's razors must, like Burke's, have operated upon blocks. But were these defects of doubting and desponding really mine? In a sense, they were; and being thus embodied in nicknames, they were forced prematurely upon my own knowledge. That was bad. Intellectually, if you are haunted with skepticism, or tendencies that way, morally, and for all purposes of action, if you are haunted with the kindred misery of desponding, it is not good to see too broadly emblazoned your own infirmities: they grow by consciousness too steadily directed upon them. And thus far there was great injustice in my brother's reproach; true it was that my eye was preternaturally keen for flaws of language, not from pedantic exaction of superfluous accuracy, but, on the contrary, from too conscientious a wish to escape the mistakes which language not rigorous is apt to occasion. So far from seeking to "pettifogulize," or to find evasions for any purpose in a trickster's minute tortuosities of construction, exactly in the opposite direction, from mere excess of sincerity, most unwillingly I found, in almost every body's words, an unintentional opening left for double interpretations. Undesigned equivocation prevails every where;[3] and it is not the caviling[Pg 305] hair-splitter, but, on the contrary, the single-eyed servant of truth, that is most likely to insist upon the limitation of expressions too wide or vague, and upon the decisive election between meanings potentially double. Not in order to resist or evade my brother's directions, but for the very opposite purpose—viz., that I might fulfill them to the letter; thus and no otherwise it happened that I showed so much scrupulosity about the exact value and position of his words, as finally to draw upon myself the vexatious reproach of being habitually a "pettifogulizer."

Meantime, our campaigning continued to rage. Overtures of pacification were never mentioned on either side. And I, for my part, with the passions only of peace at my heart, did the works of war faithfully, and with distinction. I presume so, at least, from the results. For, though I was continually falling into treason, without exactly knowing how I got into it, or how I got out of it, and, although my brother sometimes assured me that he could, in strict justice, have me hanged on the first tree we passed, to which my very prosaic answer had been, that of trees there were none in Oxford-street—[which, in imitation of Von Troil's famous chapter on the snakes of Lapland, the reader may accept, if he pleases, as a complete course of lectures on the natural history of Oxford-street]—nevertheless, by steady steps, I continued to ascend in the service; and, I am sure, it will gratify the reader to hear, that, very soon after my eighth birthday, I was promoted to the rank of major-general. Over this sunshine, however, soon swept a train of clouds. Three times I was taken prisoner; and with different results. The first time I was carried to the rear, and not molested in any way. Finding myself thus ignominiously neglected, I watched my opportunity; and, by making a wide circuit, without further accident, effected my escape. In the next case, a brief council was held over me: but I was not allowed to hear the deliberations; the result only being communicated to me—which result consisted in a message not very complimentary to my brother, and a small present of kicks to myself. This present was paid down without any discount, by means of a general subscription among the party surrounding me—that party, luckily, not being very numerous; besides which, I must, in honesty, acknowledge myself, generally speaking, indebted to their forbearance. They were not disposed to be too hard upon me. But, at the same time, they clearly did not think it right that I should escape altogether from tasting the calamities of war. And, as the arithmetic of the case seemed to be, how many legs, so many kicks, this translated the estimate of my guilt from the public jurisdiction, to that of the individual, sometimes capricious and harsh, and carrying out the public award by means of legs that ranged through all gradations of weight and agility. One kick differed exceedingly from another kick in dynamic value: and, in some cases, this difference was so distressingly conspicuous, and seemed so little in harmony with the prevailing hospitality of the evening, that one suspected special malice, unworthy, I conceive of all generous soldiership. Not impossibly, as it struck me on reflection, the spiteful individual might have a theory: he might conceive that, if a catholic chancery decree went forth, restoring to every man the things which truly belonged to him—your things to you, Cæsar's to Cæsar, mine to me—in that case, a particular brickbat fitting, as neatly as if it had been bespoke, to a contusion upon the calf of his own right leg, would be discovered making its way back into my great-coat pockets. Well, it might be so. Such things are possible under any system of physics. But this all rests upon a blind assumption as to the fact. Is a man to be kicked upon hypothesis? That is what Lord Bacon would have set his face against. However, some of my new acquaintances evidently cared as little for Lord Bacon as for me; and regulated their kicks upon principles incomprehensible to me. These contributors excepted, whose articles were unjustifiably heavy, the rest of the subscribers were so considerate, that I looked upon them as friends in disguise.

On returning to our own frontiers, I had an opportunity of displaying my exemplary greenness. That message to my brother, with all its virus of insolence, I repeated as faithfully for the spirit, and as literally for the expressions, as my memory allowed me to do: and in that troublesome effort, simpleton that I was, fancied myself exhibiting a soldier's loyalty to his commanding officer. My brother thought otherwise: he was more angry with me than with the enemy. I ought, he said, to have refused all participation in such sansculottes' insolence; to carry it was to acknowledge it as fit to be carried. "Speak civilly to my general," I ought to have told them; "or else get a pigeon to carry your message—if you happen to have any pigeon that knows how to conduct himself like a gentleman among gentlemen." What could they have done to me, said my brother, on account of my recusancy? What monstrous[Pg 306] punishments was I dreaming of, from the days of giants and ogres? "At the very worst, they could only have crucified me with the head downward, or impaled me, or inflicted the death by priné,[4] or anointed me with honey (a Jewish punishment), leaving me (still alive) to the tender mercies of wasps and hornets." One grows wiser every day; and on this particular day I made a resolution that, if again made prisoner, I would bring no more "jaw" from the Philistines. For it was very unlikely that he, whom I heard solemnly refusing to take "jaw" from whole provinces of England, would take it from the rabble of a cotton factory. If these people would send "jaw," and insisted upon their right to send it, I settled that, henceforward, it must go through the post-office.

But, in that case, had I not reason to apprehend being sawed in two? I saw no indispensable alternative of that see-saw nature. For there must be two parties—a party to saw, and a party to be sawed. And neither party has a chance of moving an inch in the business without a saw. Now, if neither of the parties will pay for the saw, then it is as good as any one conundrum in Euclid, that nobody can be sawed. For that man must be a top-sawyer, indeed, that can keep the business afloat without a saw. But, with or without the sanction of Euclid, I came to the resolution of never more carrying what is improperly called "chaff," but, by people of refinement, is called "jaw"—that is to say, this was my resolution, in the event of my being again made prisoner; an event which heartily I hoped might never happen. It did happen, however, and very soon. Again, that is, for the third time, I was made prisoner; and this time I managed ill indeed; I did make a mess of it; for I displeased the commander-in-chief in a way that he could not forget.

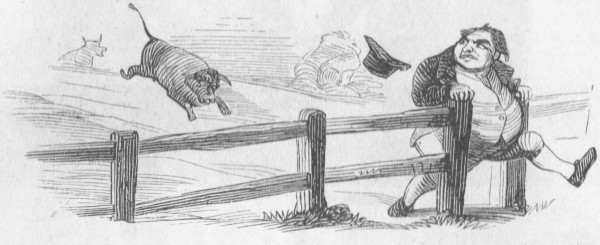

In my former captures, there had been nothing special or worthy of commemoration in the circumstances. Neither was there in this,[5] excepting that, by accident, in the second stage of the case, I was delivered over to the custody of young woman and girls; whereas the ordinary course would have thrown me upon the vigilant attentions (relieved from monotony by the experimental kicks) of boys. So far, the change was by very much for the better. I had a feeling myself—on first being presented to my new young mistresses—for to be a prisoner, I in my simplicity, believed, was to be a slave—of a distressing sort. Having always, or at least up to the completion of my sixth year, been a privileged pet, and almost, I might say, ranking among the sanctities of the household, with all its female sections, whether young or old (an advantage which I owed to a long illness, an ague, stretching over two entire years of my infancy), naturally I had learned to appreciate the indulgent tenderness of women; and my heart thrilled with love and gratitude, as often as they took me up into their arms and kissed me. Here it would have been as every where else; but, unfortunately, my introduction to these young women was in the very worst of characters. I had been taken in arms—in arms, against whom? and for what? Against their own nearest relations and connections—brothers, cousins, sweethearts; and on pretexts too frivolous to mention, if any at all. Neither was my offense of ancient date, so as to make it possible for desperate good nature to presume in me a change of heart, and a penitential horror of my past life. On the contrary, I had been taken but five minutes before, in the very act of showering brickbats on members of their own factory; and, if no great number of stones appeared to swell my pockets, it was not that I was engaged in any process of weaning myself from such fascinating missiles, but that I had liberally made over to their kinsfolk most of those which I possessed. If asked the question, it would be found that I should not myself deny the fact of being at war with their whole order. What was the meaning of that? What was it to which war, and the assumption of warlike functions, pledged a man? It pledged him, in case of an opportunity arising, to storm his enemies; that is, in my own case, to storm the houses of these young factory girls; briefly, and in plain English, to murder them all; to cut the throats of every living creature by their firesides; to float the closets in which, possibly, three generations of their family might have been huddled together for shelter, with the gore of those respectable parties. Almost every book of history in the British Museum, counting up to many myriads of volumes would tell them plainly, and in pretty nearly the very same words,[Pg 307] what they had to expect from every warrior, and therefore from me, videlicet this—that neither the guileless smiles of unoffending infancy, nor the gray hairs of the venerable patriarch sitting in the chimney corner; neither the sanctity of the matron, nor the loveliness of the youthful bride; no, nor the warlike self-devotion of the noble young man, fighting as the champion of altars and hearths; none of these searching appeals would reach my heart; neither sex nor age would confer any privilege with me; that I should put them all to the edge of the sword; that I should raze the very foundations of their old ancestral houses; having done which, I should probably plow up the ground with some bushels of Nantwich salt, mixed with bonedust from the graves of infants as a top-dressing; that, in fact, the custom of all warriors, and therefore by necessity of myself, was notoriously to make a wilderness, and to call it a pacification; with other bloody depositions in the same key, and often in the very same words.

All this was passing through my brain as the sort of explanatory introduction which, in mere honesty, I could not disown, if any body should offer it, when suddenly one young woman snatched me up in her arms, and kissed me; from her, I was passed round to others of the party, who all in turn caressed me, with scarcely an allusion to that warlike mission against them and theirs, which only had procured me the honor of an introduction to themselves in the character of captive. The too palpable fact, that I was not the person meant by nature to murder any one individual of their party, was likely enough to withdraw from their minds the counterfact—that too probably, in my military character, I might have dallied with the idea of murdering them all. Not being able to do it, as regarded any one in particular, was illogically accepted as an excuse for the military engagement that bound me to attempt it with regard to all in mass. Not only did these young people kiss me, but I (seeing no military reason against it) kissed them. Really, if young women will insist on kissing major-generals, they must expect that the generals will retaliate. One only of the crowd adverted to the character in which I came before them: to be a lawful prisoner, it struck her too logical mind that I must have been caught in some aggressive practices. "Think," she said, "of this little dog fighting, and fighting our Jack." "But," said another, in a propitiatory tone, "perhaps he'll not do so any more." I was touched by the kindness of her suggestion, and the sweet merciful sound of that same "Not do so any more," which really I fear was prompted by the charity in her that hopeth all things, and despairs of no villain, rather than by any signals of amendment that could have appeared in myself. It was well for me that they gave no time to comment on my own moral condition; for, in that case, I should have told them, that, although I had delivered, in my time, many thousands of stones for the service of their near relatives, and must, without vanity, presume that, on the ratio of one wound to a thousand shots, I had given them numerous reasons for remembering me; yet that, if so, I was sincerely sorry (which I was) for any pain I had caused—the past I regretted, and could plead only the necessities of duty. But, on the other hand, as respected the future, I could not honestly hold out any hopes of a change for the better, since my duty to my brother, in two separate characters, would oblige me to resume hostilities on the very next day. While I was preparing myself, however, for this painful exposition, my female friends saw issuing from the factory a crowd of boys not likely at all to improve my prospects. Instantly setting me down on my feet, they formed a sort of cordon sanitaire behind me, by stretching out their petticoats or aprons, as in dancing, so as to touch; and then, crying out, "Now, little dog, run for thy life," prepared themselves (I doubt not) for rescuing me, if any recapture should be effected.

But this was not effected, although attempted with an energy that alarmed me, and even perplexed me with a vague thought (far too ambitious for my years, but growing out of my chivalrous studies) that one, perhaps, if not two of the pursuing party might be possessed by some demon of jealousy, since he might have seen me reveling among the lips of that fair girlish and womanish bevy, kissed and kissing, loving and being loved; in which case from all that ever I had read about jealousy (and I had read a great deal—viz, "Othello," and Collins's "Ode to the Passions"), I was satisfied that, if again captured, I had very little chance for my life. That jealousy was a green-eyed monster, nobody could know better than I did. "Oh, my lord, beware of jealousy!" Yes; and my lord couldn't possibly beware of it more than myself; indeed, well it would have been for him had his lordship run away from all the ministers of jealousy—Iago, Cassio, Desdemona—and embroidered handkerchiefs—at the same pace of six miles an hour which kept me ahead of my infuriated pursuers. Ah, that maniac, white as a leper with flakes of cotton, can I ever forget him, that ran so far in advance of his party? What passion, but jealousy, could have sustained him in so hot a chase? There were some lovely girls in the fair company that had so condescendingly caressed me; but, doubtless, upon that sweet creature his love must have settled, who suggested, in her low, soft, relenting voice, a penitence in me that, alas! had not dawned, saying, "Yes; but perhaps he will do so no more." Thinking, as I ran, of her beauty, I felt that this jealous demoniac must fancy himself justified in committing seven times seven murders upon me, if he should have it in his power. But, thank heaven, if jealousy can run six miles an hour, there are other passions, as for instance, fear, that can run, upon occasion, six and a half; so, as I had the start[Pg 308] of him (you know, reader), and not a very short start—thanks be to the expanded petticoats of my dear female friends! naturally it happened that the green-eyed monster came in second best. Time luckily was precious with him; and therefore, when he had chased me into the by-road leading down to Greenhay, he turned back; and I, with somewhat sorrowful steps, on the consideration that this scene might need to be all acted over again, when Green-eyes might happen to have better luck, and being unhappy, besides, at having to number so many kind-hearted girls among Philistines and daughters of Gath, pensively pursued my way to the gates of Greenhay. Pensively is not the word that meets the realities of the case. I was unhappy, in the profoundest sense, and not from any momentary accident of distress that might pass away and be forgotten, but from deep glimpses which now, as heretofore, had opened themselves, as occasions arose, into the interior sadnesses, and the inevitable conflicts of life. I knew—I anticipated to a dead certainty—that my brother would not hear of any merit belonging to the factory population whom every day we had to meet in battle; on the contrary, even submission on their part, and willingness to walk penitentially through the Furcæ Caudinæ, would hardly have satisfied his sense of their criminality. Continually, indeed, as we came in view of the factory, he used to shake his fist at it, and say, in a ferocious tone of voice, "Delenda est Carthago!" And certainly, I thought to myself, it must be admitted by every body that the factory people are inexcusable in raising a rebellion against my brother. But still rebels were men, and sometimes were women; and rebels, that stretch out their petticoats like fans for the sake of screening one from the hot pursuit of enemies with fiery eyes (green or otherwise), really are not the sort of people that one wishes to hate.

Homeward, therefore, I drew in sadness, and little doubting that hereafter I might have verbal feuds with my brother on behalf of my fair friends, but not dreaming how much displeasure I had already incurred by my treasonable collusion with their caresses. That part of the affair he had seen with his own eyes from his position on the field; and then it was that he left me indignantly to my fate, which, by my first reception, it was easy to see would not prove very gloomy. When I came into our own study, I found him engaged in preparing a bulletin (which word was just then traveling into universal use), reporting briefly the events of the day. Drawing, as I shall again have occasion to mention, was among his foremost accomplishments; and round the margin of the border ran a black border, ornamented with cypress, and other funeral emblems. When finished, it was carried into the room of Mrs. Evans. This Mrs. Evans was an important person in our affairs. My mother, who never chose to have any direct communication with her servants, always had a housekeeper for the regulation of all domestic business; and the housekeeper for some years at this period was this Mrs. Evans. Into her private parlor, where she sat aloof from the under servants, my brother and I had the entrée at all times, but upon very different terms of acceptance: he, as a favorite of the first class; I, by sufferance, as a sort of gloomy shadow that ran after his person, and could not well be shut out if he were let in. Him she admired in the very highest degree; myself, on the contrary, she detested, which made me unhappy. But then, in some measure, she made amends for this, by despising me in extremity, and for that I was truly thankful—I need not say why, as the reader already knows. Why she detested me, so far as I know, arose out of my reserve and thoughtful abstraction. I had a great deal to say, but then I could say it only to a very few people, among whom Mrs. Evans was certainly not one; and when I did say any thing, I fear that my dire ignorance and savage sincerity prevented my laying the proper restraints upon my too liberal candor; and that could not prove acceptable to one who thought nothing of working for any purpose, or for no purpose, by petty tricks, or even falsehoods—all which I held in stern abhorrence, that I was at no pains to conceal. The bulletin, on this occasion, garnished with its pageantry of woe, cypress wreaths, and arms reversed, was read aloud to Mrs. Evans, indirectly therefore to me. It communicated, with Spartan brevity, the sad intelligence (but not sad to Mrs. E.), "that the major-general had forever disgraced himself, by submitting to the ... caresses of the enemy." I leave a blank for the epithet affixed to "caresses," not because there was any blank, but, on the contrary, because my brother's wrath had boiled over in such a hubble-bubble of epithets, some only half-erased, some doubtfully erased, that it was impossible, out of the various readings, to pick out the true classical text. "Infamous," "disgusting," and "odious," struggled for precedency; and infamous they might be; but on the other affixes I held my own private opinions. For some days, my brother's displeasure continued to roll in reverberating thunders; but at length it growled itself to rest; and at last he descended to mild expostulations with me, showing clearly, in a series of general orders, what frightful consequences must ensue, if major-generals (as a general principle) should allow themselves to be kissed by the enemy.

Upward of two thousand years ago, perhaps three, a company of merchants, who had a cargo of nitre on board their ship, were driven by the winds on the shores of Galilee, close to a small stream that runs from the foot of Mount Carmel. Being here weather-bound till the storm abated, they made preparations for cooking their food on the strand; and not finding stones to rest their vessels upon, they used some lumps[Pg 309] of nitre for that purpose, placing their kettles and stew-pans on the top, and lighting a strong fire underneath. As the heat increased, the nitre slowly melted away, and flowing down the beach, became mixed up with the sand, forming, when the incorporated mass cooled down, a singularly beautiful, transparent substance, which excited the astonishment and wonder of the beholders.

Such is the legend of the origin of Glass.

A great many centuries afterward—that is to say, toward the close of the fifteenth century of the Christian era—when some of the secrets of the glass-house, supposed to have been known to the ancients, were lost, and the simple art of blowing glass was but scantily cultivated—an artificer, whose name has unfortunately escaped immortality, while employed over his crucible accidentally spilt some of the material he was melting. Being in a fluid state it ran over the ground till it found its way under one of the large flag-stones with which the place was paved, and the poor man was obliged to take up the stone to recover his glass. By this time it had grown cold, and to his infinite surprise he saw that, from the flatness and equality of the surface beneath the stone, it had taken the form of a slab—a form which could not be produced by any process of blowing then in use.

Such was the accident that led to the discovery of the art of casting Plate-Glass.

These are the only accidents recorded in the History of Glass. For the rest—the discovery of its endless capabilities and applications—we are indebted to accumulated observation and persevering experiment, which, prosecuting their ingenious art-labors up to the present hour, promise still farther to enlarge the domain of the Beautiful and the Useful.

The importance of glass, and the infinite variety of objects to which it is applicable, can not be exaggerated. Indeed it would be extremely difficult to enumerate its properties, or to estimate adequately its value. This thin, transparent substance, so light and fragile, is one of the most essential ministers of science and philosophy, and enters so minutely into the concerns of life, that it has become indispensable to the daily routine of our business, our wants, and our pleasures. It admits the sun and excludes the wind, answering the double purpose of transmitting light and preserving warmth; it carries the eyes of the astronomer to the remotest region of space; through the lenses of the microscope it develops new worlds of vitality which, without its help, must have been but imperfectly known; it renews the sight of the old, and assists the curiosity of the young; it empowers the mariner to descry distant ships, and to trace far-off shores, the watchman on the cliff to detect the operations of hostile fleets and midnight contrabandists, and the lounger in the opera to make the tour of the circles from his stall; it preserves the light of the beacon from the rush of the tempest, and softens the flame of the lamps upon our tables; it supplies the revel with those charming vessels in whose bright depths we enjoy the color as well as the flavor of our wine; it protects the dial whose movements it reveals; it enables the student to penetrate the wonders of nature, and the beauty to survey the marvels of her person; it reflects, magnifies, and diminishes; as a medium of light and observation its uses are without limit; and as an article of mere embellishment, there is no form into which it may not be moulded, or no object of luxury to which it may not be adapted.

Yet this agent of universal utility, so valuable and ornamental in its applications, is composed of materials which possess in themselves literally no intrinsic value whatever. Sand and salt form the main elements of glass. The real cost is in the process of manufacture.

Out of these elements, slightly varied according to circumstances, are produced the whole miracles of the glass-house. To any one, not previously acquainted with the component ingredients, the surprise which this information must naturally excite will be much increased upon being apprised of a few of the peculiarities or properties of glass. Transparent in itself, the materials of which it is composed are opaque. Brittle to a proverb when cold, its tenuity and flexibility when hot are so remarkable that it may be spun into filaments as delicate as cobwebs, drawn out like elastic threads till it becomes finer than the finest hair, or whisked, pressed, bent, folded, twisted or moulded into any desired shape. It is impermeable to water, suffers no diminution of its weight or quality by being melted down, is capable of receiving and retaining the most lustrous colors, is susceptible of the most perfect polish, can be carved and sculptured like stone or metal, never loses a fraction of its substance by constant use, and, notwithstanding its origin, is so insensible to the action of acids that it is employed by chemists for purposes to which no other known substance can be applied.

The elasticity and fragility of glass are among its most extraordinary phenomena. Its elasticity exceeds that of almost all other bodies. If two glass balls are made to strike each other at a given force, the recoil, by virtue of their elasticity, will be nearly equal to the original impetus. Connected with its brittleness are some very singular facts. Take a hollow sphere, with a hole, and stop the hole with your finger, so as to prevent the external and internal air from communicating, and the sphere will fly to pieces by the mere heat of the hand. Vessels made of glass that has been suddenly cooled possess the curious property of being able to resist hard blows given to them from without, but will be instantly shivered by a small particle of flint dropped into their cavities. This property seems to depend upon the comparative thickness of the bottom. The thicker the bottom is, the more certainty of breakage by this experiment. Some of these vessels, it is stated, have resisted the[Pg 310] strokes of a mallet, given with sufficient force to drive a nail into wood; and heavy bodies, such as musket-balls, pieces of iron, bits of wood, jasper, bone, &c., have been cast into them from a height of two or three feet without any effect; yet a fragment of flint, not larger than a pea, let fall from the fingers at a height of only three inches, has made them fly. Nor is it the least wonderful of these phenomena that the glass does not always break at the instant of collision, as might be supposed. A bit of flint, literally the size of a grain, has been dropped into several glasses successively, and none of them broke; but, being set apart and watched, it was found that they all flew in less than three-quarters of an hour. This singular agency is not confined to flint. The same effect will be produced by diamond, sapphire, porcelain, highly-tempered steel, pearls, and the marbles that boys play with.[6]

Several theories have been hazarded in explanation of the mystery; but none of them are satisfactory. Euler attempted to account for it on the principle of percussion; but if it were produced by percussion the fracture would necessarily be instantaneous. The best solution that can be offered, although it is by no means free from difficulties, refers the cause of the disruption to electricity. There is no doubt that glass, which has been suddenly cooled, is more electric than glass that has been carefully annealed—a process which we will presently explain; and such glass has been known to crack and shiver from a change of temperament, or from the slightest scratch. The reason is obvious enough. When glass is suddenly cooled from the hands of the artificer, the particles on the outer side are rapidly contracted, while those on the inner side, not being equally exposed to the influence of the atmosphere, yet remain in a state of expansion. The consequence is that the two portions are established on conflicting relations with each other, and a strain is kept up between them which would not exist if the whole mass had undergone a gradual and equal contraction, so that when a force is applied which sets in motion the electric fluid glass is known to contain, the motion goes on propagating itself till it accumulates a power which the irregular cohesion of the particles is too weak to resist. This action of the electric fluid will be better understood from an experiment which was exhibited before the Royal Society upon glass vessels with very thick bottoms, which, being slightly rubbed with the finger, broke after an interval of half an hour.[7] The action of the electric fluid in this instance is sufficiently clear; but why the contact with fragments of certain bodies should produce the same result, or why that result is not produced by contact with other bodies of even greater size and specific gravity, is by no means obvious.

Among the strangest phenomena observed in glass are those which are peculiar to tubes. A glass tube placed in a horizontal position before a fire, with its extremities supported, will acquire a rotatory motion round its axis, moving at the same time toward the fire, notwithstanding that the supports on which it rests may form an inclined plane the contrary way. If it be placed on a glass plane—such as a piece of window-glass—it will move from the fire, although the plane may incline in the opposite direction. If it be placed standing nearly upright, leaning to the right hand, it will move from east to west; if leaning to the left hand, it will move from west to east; and if it be placed perfectly upright, it will not move at all. The causes of these phenomena are unknown, although there has been no lack of hypotheses in explanation of them.[8]

It is not surprising that marvels and paradoxes should be related of glass, considering the almost incredible properties it really possesses. Seeing that it emits musical sounds when water is placed in it, and it is gently rubbed on the edges; that these sounds can be regulated according to the quantity of water, and that the water itself leaps, frisks, and dances, as if it were inspired by the music; seeing its extraordinary power of condensing vapor, which may be tested by simply breathing upon it; and knowing that, slight and frail as it is, it expands less under the influence of heat than metallic substances, while its expansions are always equable and proportioned to the heat, a quality not found in any other substance, we can not be much astonished at any wonders which are superstitiously or ignorantly attributed to it, or expected to be elicited from it. One of the most remarkable is the feat ascribed to Archimedes, who is said to have set fire to the Roman fleet at the siege of Syracuse by the help of burning-glasses. The fact is attested by most respectable authorities,[9] but it is only right to add, that it is treated as a pure fable by Kepler and Descartes, than whom no men were more competent to judge of the possibility of such an achievement. Tzetzez relates the matter very circumstantially; he says that Archimedes set fire to Marcellus's navy by means of a burning glass composed of small square mirrors, moving every way upon hinges; which, when placed in the sun's rays, directed them upon the Roman fleet, so as to reduce it to ashes at the distance of a bow-shot. Kircher made an experiment founded upon this minute description, by which he satisfied himself of the practicability of at least obtaining an extraordinary condensed power of this kind. Having collected the sun's rays into a focus, by a number of plain mirrors, he went on increasing the number of mirrors until at last he produced an intense degree of solar[Pg 311] heat; but it does not appear whether he was able to employ it effectively as a destructive agent at a long reach. Buffon gave a more satisfactory demonstration to the world of the capability of these little mirrors to do mischief on a small scale. By the aid of his famous burning-glass, which consisted of one hundred and sixty-eight little plain mirrors, he produced so great a heat as to set wood on fire at a distance of two hundred and nine feet, and to melt lead at a distance of one hundred and twenty, and silver at fifty; but there is a wide disparity between the longest of these distances and the length of a bowshot, so that the Archimedean feat still remains a matter of speculation.

In the region of glass, we have a puzzle as confounding as the philosopher's stone (which, oddly enough, is the name given to that color in glass which is known as Venetian brown sprinkled with gold spangles), the elixir vitæ, or the squaring of the circle, and which has occasioned quite as much waste of hopeless ingenuity. Aristotle, one of the wisest of men, is said, we know not on what authority, to have originated this vitreous perplexity by asking the question. "Why is not glass malleable?" The answer to the question would seem to be easy enough, since the quality of malleability is so opposed to the quality of vitrification, that, in the present state of our knowledge (to say nothing about the state of knowledge in the time of Aristotle) their co-existence would appear to be impossible. But, looking at the progress of science in these latter days, it would be presumptuous to assume that any thing is impossible. Until, however, some new law of nature, or some hitherto unknown quality shall have been discovered, by which antagonist forces can be exhibited in combination, the solution of this problem may be regarded as at least in the last degree improbable.

Yet, in spite of its apparent irreconcilability with all known laws, individuals have been known to devote themselves assiduously to its attainment, and on more than one occasion to declare that they had actually succeeded, although the world has never been made the wiser by the disclosure of the secret. A man who is possessed with one idea, and who works at it incessantly, generally ends by believing against the evidence of facts. It is in the nature of a strong faith to endure discouragement and defeat with an air of martyrdom, as if every fresh failure was a sort of suffering for truth's sake. And the faith in the malleability of glass has had its martyrology as well as faith in graver things. So far back as the time of Tiberius, a certain artificer, who is represented to have been an architect by profession, believing that he had succeeded in making vessels of glass as strong and ductile as gold or silver, presented himself with his discovery before the Emperor, naturally expecting to be rewarded for his skill. He carried a handsome vase with him, which was so much admired by Tiberius that, in a fit of enthusiasm, he dashed it upon the ground with great force to prove its solidity, and finding, upon taking it up again, that it had been indented by the blow, he immediately repaired it with a hammer. The Emperor, much struck with so curious an exhibition, inquired whether any body else was acquainted with the discovery, and being assured that the man had strictly preserved his secret, the tyrant instantly ordered him to be beheaded, from an apprehension that if this new production should go forth to the world it would lower the value of the precious metals.[10] The secret, consequently, perished. A chance, however, arose for its recovery during the reign of Louis XIII., a period that might be considered more favorable to such undertakings; but unfortunately with no better result. The inventor on this occasion submitted a bust formed of malleable glass to Cardinal Richelieu, who, instead of rewarding him for his ingenuity, sentenced him to perpetual imprisonment, on the plea that the invention interfered with the vested interests of the French glass manufacturers.[11] We should have more reliance on these anecdotes of the martyrs of glass, if they had bequeathed to mankind some clew to the secret that is supposed to have gone to the grave with them. To die for a truth, and at the same time to conceal it, is not the usual course of heroic enthusiasts.

Many attempts have been made to produce a material resembling glass that should possess the quality of malleability, and respectable evidence is not wanting of authorities who believed in its possibility, and who are said to have gone very near to its accomplishment. An Arabian writer[12] tells us that malleable glass was known to the Egyptians; but we must come closer to our own times for more explicit and satisfactory testimony. Descartes thought it was possible to impart malleability to glass, and Boyle is reported to have held the same opinion. But these are only speculative notions, of no further value than to justify the prosecution of experiments. Borrichius, a Danish physician of the seventeenth century, details an experiment by which he obtained a malleable salt, which led him to conclude that as glass is for the most part only a mixture of salt and sand, he saw no reason why it should not be rendered pliant. The defect of his logic is obvious; but, setting that aside, the fallacy is practically demonstrated by his inability to get beyond the salt. Borrichius also thought that the Roman who made the vase for Tiberius, may have successfully used antimony as his principal ingredient. Such suppositions, however, are idle in an experimental science which furnishes you at once with the means of putting their truth or falsehood to the test. There is a substance known to modern[Pg 312] chemistry, luna cornea, a solution of silver, which resembles horn or glass, is transparent, easily put into fusion, and is capable of bearing the hammer. Kunkel thought it was possible to produce a composition with a glassy exterior that should possess the ductile quality; but neither of these help us toward an answer to Aristotle's question. Upon a review of the whole problem, and of every thing that has been said and done in the way of experiment and conjecture, we are afraid we must leave it where we found it. The malleability of glass is still a secret.

Dismissing history and theory, we will now step into the glass-house itself, where the practical work of converting sand into goblets, vases, mirrors, and window-panes is going forward with a celerity and accuracy of hand and head that can not fail to excite wonder and admiration. As the whole agency employed is that of heat, the interior of the manufactory consists of furnaces specially constructed for the progressive processes to which the material is subjected before it is sent out perfected for use. Look round this extensive area, where you see numbers of men in their shirt-sleeves, with aprons before them, and various implements in their hands, which they exercise with extraordinary rapidity, and you will soon understand how the glittering wonders of glass are produced. Of these furnaces there are three kinds, the first called the calcar, the second the working furnace, and the third the annealing oven, or lier.

The calcar, built in the form of an oven, is used for the calcination of the materials, preliminary to their fusion and vitrification. This process is of the utmost importance: it expels all moisture and carbonic acid gas, the presence of which would hazard the destruction of the glass-pots in the subsequent stages of the manufacture, while it effects a chemical union between the salt, sand, and metallic oxides, which is essential to prevent the alkali from fusing and volatilizing, and to insure the vitrification of the sand in the heat of the working furnace, to which the whole of the materials are to be afterwards submitted.