FOR THE WHITE CHRIST

FOR THE

WHITE CHRIST

A Story

of

The Days of Charlemagne

BY

Robert Ames Bennet

Having Pictures and Designs by

Troy & Margaret West Kinney

Chicago

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1905

Copyright,

By A. C. McClurg & Co.

1905

Published March 18, 1905

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All rights reserved

The University Press, Cambridge, U.S.A.

To the Memory

of

My Mother

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

All the chapter headings of this story are taken from lays which were sung by harpers and skalds before the high-seats of heathen Norse chiefs and in the halls of the Anglo-Saxon kings, while England was yet a heptarchy and the name of Mohammed but little known to men even on the shores of the far-distant Bosphorus.

In most instances the selections are from Magnusson and Morris's beautiful translations of "The Volsunga Saga, and Certain Songs from the Elder Edda." The spirited lines from "Beowulf," "Maldon," "Finnesburh," and "Andreas" were found in Gummerle's "Germanic Origins." The translation of "Brunanburh" is by Tennyson.

Apology is due for occasional alterations and elisions, all of which will readily be detected by students of the wonderful poetic fragments which have come down to us from our Norse and Teutonic forefathers.

R. A. B.

Denver, January 1, 1905.

ILLUSTRATIONS

"'Bend lower, king's daughter--little vala with eyes like dewy violets!'" . . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

"White to the lips, the young sea-king turned to his enemy"

"'Love!' she cried, half hissing the word. 'You speak of love,--you, the heathen outlander!'"

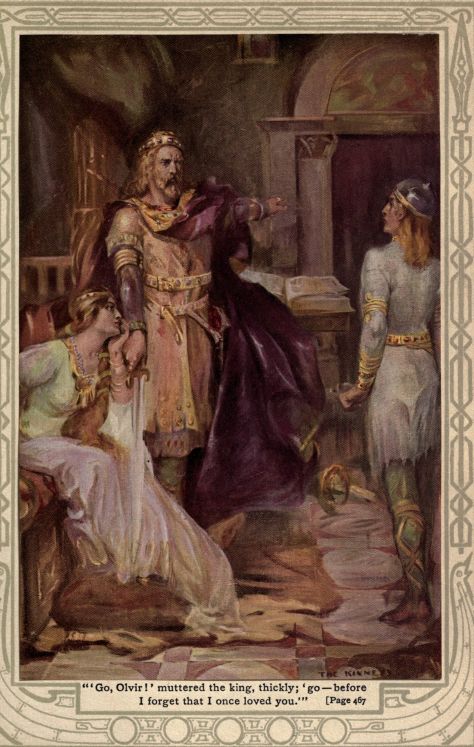

"'Go, Olvir!' muttered the king, thickly; 'go--before I forget that I once loved you'"

FOR THE WHITE CHRIST

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER I

Early of an April morning of the year 778, a broad-beamed Frisian trade-ship was drifting with the ebb-tide down the Seine estuary. Wrapped about by the morning vapors, the deeply laden little craft floated on the stream like a dreamship. The mists shut out all view of sky and land and sea. From the quarter-deck, the two men beside the steer-oar could scarcely see across the open cargo-heaped waist to where, gathered silently about the mast, a dozen or so drowsy sailors stood waiting for the morning breeze.

The remainder of the crew lay sprawled upon the casks and bales of merchandise, side by side with a score of Frankish warriors. All alike were heavy with drunken slumber. The shipmaster, a squat red-haired man of great girth, regarded the overcome wassailers with an indifferent eye; but the tall warrior beside him appeared far from pleased by the sight.

"Is it so you rule your ship, Frisian?" he demanded. "You should have stopped the wassail by midnight. Here we swim on the treacherous sea, while our men lie in drunken stupor."

"We are yet in the stream, lord count," replied the shipmaster. "As to my Frisians, a dash of salt water will soon rouse them. If your landsmen are farther gone, what odds? Drunk or sober, they 'll be alike useless when we strike rough seas."

The Frank's face lit with a smile as quick as its frown.

"There you are mistaken, Frisian," he said. "A man may bear the wild waters no love, yet owe them no fear. Twice I have crossed this narrow sea, as envoy of our Lord Karl to the kings of the Anglo-Saxons, and my henchmen sailed with me."

"Yours are king's men, lord count,--all busked like chiefs."

"Man for man, I would pit them against the followers of any leader. Better a few picked warriors, so armed, than twice their number of common freemen."

"Well said!" muttered the Frisian; "a choice following. I 'd wager on them, even against Dane steel--except the sea-wolves of Olvir Elfkin."

"Olvir Elfkin? You speak of a liegeman of Sigfrid, King of the Nordmannian Danes?"

"No, lord count; Earl Olvir is far too proud to let himself be called the man of any king. I sail far on my trade-farings. At the fair of Gardariki, across the great gulf from the Swedes, I saw the Norse hero. His father was one-time king of the Trondir, a folk who dwell beneath the very eaves of the ice-giants. His mother was an elf-maiden from the far Eastland. Another time I will tell you that tale, lord count. I had it from Floki the Crane, my Norse sword-brother. But now I speak of Earl Olvir's following. He is so famed in the North that the greatest heroes think it honor to fight beneath his banner; and he rules the mail-clad giants as our great King Karl rules his counts. Six seasons in all he has come swooping south from his ice-cliffs to harry the coasts of Jutland and Nordmannia; and though even now he is little more than a bairn in years, each time that he steered about for his home fiord he left a war-trail of sunken longships to mark his outbound course."

"I heard much of such sea-fights from that mighty Dane hero Otkar,--he who went over to King Desiderius and fought against our Lord Karl in the Lombard war."

"Ay; who has not heard of Otkar Jotuntop,--Otkar the Dane? This very Earl Olvir of whom I spoke is of kin to the hero."

"Even I have heard of Lord Otkar," called out a childish voice, and the speaker sprang lightly up the deck ladder. She was a lissome little maiden, barely out of childhood, yet possessed of an unconscious dignity of look and bearing that well matched her rich costume.

The warrior bowed low to her half-shy, half-gay greeting, and smiling down into her violet eyes, he replied in a tone of tender deference, "The Princess Rothada is early awake. Shall I not call the tiring-woman?"

The girl put up her hand to touch the coronet which bound her chestnut hair, and her glance passed in naive admiration down the gold-embroidered border of her loose-sleeved overdress.

"Princess! princess!" she cried gayly. "To think that only four days have gone since with Gisela and the other maidens I waited upon the blessed sisters! And now I wear a ring and silken dresses, and the greatest war-count of the king my father--but are you not my kinsman, lord count?"

"Your cousin, little princess. My mother was a sister of our lord king."

"Then you shall no longer call me princess, but Rothada, and I shall call you Roland. Few maidens can own kinsmen so tall and grand!" and Rothada stared up in half-awed admiration at the count's war-dinted helmet and shining scale-hauberk.

The warrior's blue eyes glowed, but there was no vanity with his frank pleasure.

"Saint Michael give me skill to shield you from all harm!" he said.

"Surely he has already strengthened your arm. In all the land you stand second only to the king my father!--But you spoke of Otkar the Dane. Tell me more about him, cousin. Already I know that he was a heathen count from the far North, more learned than any monk or priest, and in battle mightier even than my father. Two winters ago there came to Chelles a maiden who knew many tales of the Saxon and Lombard wars,--Fastrada--"

Roland's cheeks flushed, and he stooped forward eagerly.

"Fastrada!" he exclaimed. "You knew her?"

"For a winter's time---"

"You will meet her again. She is now one of the queen's maidens,--the fairest of them all."

"Then you like her, cousin," replied Rothada, with innocent candor. "It was different with Gisela and me. Many of the maidens feared her, and she broke the holy rules and talked so much of warriors that the good abbess sent her away. Yet that is long since--she may have changed."

"None could but like her now, child," replied Roland, softly. Yet even as he spoke, some unwelcome thought blotted the smile from his face. He frowned and stared moodily out into the wavering mists.

The girl followed his look, and the sight of the water alongside recalled her to the present.

"See, kinsman," she said, with a sudden return of gayety, "the sailors spread the sail. How long shall we be upon the sea until we reach the Garonne?"

"Were we travelling by land, I could tell you, little princess. But I am no sea-count. Our shipmaster can best answer you."

The Frisian turned to the daughter of the great king with an uncouth attempt at a bow.

"Wind and wave are fickle, maiden, and no sea is rougher than the Vascon Bay," he grumbled. "But with fair wind I land you at Casseneuil while the lord count's horsemen yet ride in Aquitania."

"That I doubt, man," said Roland. "Yet here is promise of fair sailing. The sun melts the mists, and with it comes the breeze to sweep them away."

"Ay; the fog breaks. Between sun and wind we 'll see both shores before the ship gains full headway."

"I already see-- Look, man! Can we be so close inshore? What flashes so brightly?"

The Frisian wheeled about, an anxious frown lowering beneath his shaggy forelock. His alarm was only too well founded. A puff of the freshening breeze swept before it the last bank of vapor, and revealed with startling clearness two grim black hulls, along whose sweeping bulwarks hung rows of yellow shields. On the lofty prows shone the gilded dragon-heads whose glitter had first caught Roland's eye. The single masts were bare of yard and sail; but along each side a dozen or more great sweeps thrust out beneath the scaly shield-row like the legs of a dragon.

"Danes!" gasped the Frisian, and from the grimly beautiful viking ships, every line of which spoke of grace and speed, he turned a despairing eye upon his clumsy trade-ship.

"Lost! lost!" he cried. "Already they come about to give chase--Garpike and the lame duck! Paul seize all vikings!"

"No, Frisian," rejoined Roland. "These, in truth, are war-ships; yet they come in peace. Dane or other, they dare not attack us on the coast of Neustria."

As though in retort to this proud boast, a red shield swung up to each Danish masthead, and across the water rolled a fierce war-cry. Roused by the wild shout, all the sleepers in the trade-ship's waist sprang to their feet. But while the Frisians huddled about the mast like frightened sheep, the Franks met the sudden danger with the steadiness of seasoned warriors. At a sign from their lord, they crept aft, sword and axe in hand, and crouched on the deck behind the bulwarks. As they made ready for battle, Roland caught up the hand of Rothada, who stood gazing at the viking ships in mingled terror and admiration.

"Princess," he said, "the heathen shoot far with bow and sling. It is time you sought shelter below. For a while you can there lie in safety."

"But you, cousin? The Dane ships swarm with warriors. You and your men will all be slain! Do not fight them, Roland! Let there be no bloodshed."

"A wise maiden!" cried the shipmaster. "Mark the odds,--one stroke brings death to us all. Yield, lord Frank! What if they give two or three to Odin? The rest they 'll spare for thralls or set free for wergild."

"Ah, Roland, yield, then! Do not anger the terrible heathen. My father will soon ransom us."

"And what will he say to his daughter's faithless warder,--to the coward who, without a blow, yielded a king's child into heathen thraldom?--By my sword, the Danes take you only over the corpse of the last Frank in this ship!"

But proudly as he spoke, when he swung the girl down from the deck, the count's heart sickened at thought of her helplessness. How would the little cloister-maiden fare in the hands of the fierce sea-thieves? The anguish of the thought filled him with renewed rage. He gripped his sword-hilt.

"Now to die, with a score of Danes for death-bed," he muttered.

Then a sudden hope flashed from his blue eyes. He seized the steersman by the shoulder, and shouted joyfully: "Ho, Frisian; we may yet go free! Cast over the cargo! The breeze freshens; we 'll outsail the thieves!"

"Only another viking could do that--yet the cloth bales will float--the Danes may linger to pick them up. A good trick, if old-- But what-- Curse of the foul fiend! Look to seaward--three more longships--across our course!"

"The race is run! Strike sail, man, and go forward to your sailors. You and they may so save your skins. I and my men die here."

"I, too, can die," answered the shipmaster, stolidly, and he drew a curved sword-knife from his belt.

"Go; you wear no war-gear," commanded Roland.

"I will fight berserk, as they say in the North."

"Then take my shield, and with it the thanks of a Frankish count. No braver man ever fought beside me."

The Frisian took the shield, unmoved by the praise.

"Once I had a Northman for sword-fellow. They called him Floki the Crane. From him I learned the ways of vikings. They know how to die."

"No less do my henchmen," rejoined Roland, and he shook the great mane of tawny hair which fell about his shoulders. Here was no Romanized Neustrian, tainted and weakened by the vices of a corrupt civilization, but a German warrior,--an Austrasian of pure blood. He watched the approaching Danes, eager for battle.

The Frisian, as he slipped the shield upon his arm, stared at the Frank with a look of dull admiration. But when an arrow whistled close overhead, he wheeled hastily about and shouted command to strike sail. The order was obeyed with zeal, for the crew stood trembling in dread of the Danish missiles. Down rushed the great wool sheet, and an exultant shout rolled out from the pursuing longships. Count Roland smiled grimly.

"Hearken, men!" he said; "the heathen think we yield. They lay aside bow and sling. All will be axe and sword play. They shall learn the taste of Frankish steel!"

The Frisian shook his head: "No, no, lord count. They 'll board on either quarter, and overwhelm us. Your men are too scattered. The Danes--"

"No, by my sword! The leading craft sheers off."

"She steers to meet the seaward ships! The Norns smile upon us, Frank. We are doomed; but many a Dane goes before us to Hel's Land!"

"Brave words, man, though strange on the lips of a Christian," replied Roland, and he drew his short-hafted battle-axe. "Now, men, make ready. The Dane ship closes like a hound on the deer's flank. It will find the stag at bay! When I cast my axe, leap up and strike for Christ and king."

A low murmur came back from the crouching Franks, and they gripped their weapons with added firmness. They were picked men, who had fought in all the wars of Karl and of Pepin his father. One, a hoary giant of sixty, could even boast that as a boy he had swung a sword in the fateful battle of Tours, when Karl the Hammer had shattered the conquering hosts of Mohammed. Death had no terrors for such iron-hearted warriors. All they asked was the chance to sell their lives dearly. Like hunted wolves, they lay in wait, while the shouting Danes rowed up to seize their prize.

CHAPTER II

Already the longship lay close astern. A harsh command sent the oars rattling in through their ports; and as the dragon prow overlapped the flank of the quarry, a dozen grappling-hooks fell clanking across the bulwark. Half the longship's crew swarmed in the bows,--a wild-eyed, skin-clad band, staring with fierce greed at the casks and bales with which the trade-ship was laden. None of them looked twice at the two men standing so quietly in the middle of the deck. In their eagerness for loot, all pressed forward to board the trade-ship, and so little did they dream of resistance that many bore their weapons sheathed.

They were soon to learn their mistake. As the first Dane leaped upon the bulwark, Roland swept his axe overhead and hurled it at the luckless viking. Across the front the Dane's wolfskin serk was thickly sewn with iron rings; but the axe-blade shore through iron and hide like cloth, and buried itself in the viking's breast.

The surprise could not have been more complete. As the axe flashed over their heads, the hidden warriors sprang up and fell upon the Danes with all the fury of despair. Their lord and the Frisian sprang forward beside them, and the Frankish blades threshed across the bulwarks in swift strokes that cut down a dozen vikings before they could guard themselves. More in astonishment than dismay, the foremost Danes recoiled upon their fellows, causing a jam and confusion that prolonged the vantage of the Franks. Like flails the weapons of the grey warriors beat upon the round shields of the heathen.

"Strike! strike!" they shouted in the fierce joy of battle. "Christ and king! Down with the pagans! death to the sea-thieves!"

On the right the shipmaster thrust his pointed sword-knife into the faces of the enemy; on the left the axe of the hoary giant of Tours fell like Thor's hammer; while between the two, Roland, wielding his sword in both hands, cut down a Dane with every blow. His eyes flashed with the fire of battle, and as he struck he shouted tauntingly: "Ho, Danes! ho, sea-thieves! here is sword-play! Run, cast your spears from shelter! Frank steel bites deep!"

The answer was a roar of fury. The death of their fellows only roused the Danes to wild rage. Their huge bodies quivered, and eyes yet more fiery than Roland's flamed with the battle-light. The air rang with the clash of weapons, and the terrible war-cry swelled into a deafening roar,--"Thor aid! Thor aid! Death to the Frank dogs!"

In a mass the vikings surged forward and leaped at the bulwark. Vainly the Franks sought to withstand the shock. The crashing strokes of Roland's sword kept clear all the space within its sweep; but on either side the vikings burst across the bulwark in overwhelming numbers. Shield clashed against shield, and blades beat upon helmet and hauberk with the clang of a hundred smithies. No warriors could long withstand such odds. Down went the Frisian under the blade of a berserk axe, and after him fell the old giant of Tours, a throttled Dane in his grip. Then four more Franks fell, all together, and the whole line reeled back across the deck. The defence was broken. The Danes yelled in fierce triumph and surged forward to thrust their handful of foes over into the sea. Many warriors so hard pressed would have flung down their weapons and begged for quarter. Not so the henchmen of the king's kin.

"Back to back!" called their count, and for a moment he checked the Danish rush by the sweep of his single sword. Brief as was the respite, it gave his followers time to rally. They sprang together and ringed about their leader in a shieldburg that all the wild fury of the vikings could not break. Like their lord, these grey warriors were Rhinemen of pure German blood. Between them and their foes was slight difference other than the veneer of a nominal Christianity. Drunk with the wine of battle, they whirled their reddened blades and rejoiced to slay and be slain in Odin's game. One by one, they staggered and fell, striking even in the death-agony. Those who were left only narrowed their ring to close the gaps, and fought on.

Of all the virtues, Northman and Teuton alike gave first place to courage. Wonder seized the Danes at the very height of their blood-fury. Never before had even they, the fierce sea-wolves, witnessed such sword-play. Overcome by admiration, many drew back as the last few Franks fell dying. When Roland stood alone within their circle, by common impulse they lowered their weapons and shouted to spare the hero. Only one voice dissented--but it was the voice of the Danish chief.

The sea-king had been steering his ship, and so unexpected and furious was the fight that its end came before he could force a way through the press of his own men. Enraged that he had failed to come to blows, he now pushed to the front, a grand and imposing figure in his scale hauberk and gold-winged helmet. But beneath the helmet's bright rim lowered a face more brutal and ferocious than a Saxon outlaw's.

"Way!" he shouted; and as the vikings parted, he stepped over the slain to where Roland leaned heavily upon his sword.

"So-ho!" he jeered, and he eyed the gasping Frank with cruel satisfaction. "They breed bears in the South worth the baiting."

Roland's eyes flashed as he answered: "Heathen boar! you may well talk of baiting. Count your men who have fallen. Had I half my strength, I 'd send you with them to burn in Tartarus!"

"Had you all your strength, Frank, I should strike off your hands with Ironbiter my sword, and cast you overboard to the sea-god. As it is, I 'll take you thrall and break your back on Thor's Stone at the Winter Sacrifice. Next Yule the followers of Hroar the Cruel shall drink to Thor and Frey from the skull of Earl Roland, the kin of the Frank king."

The count started in astonishment.

"Tell me, Dane!" he cried; "how do you know my name? Not by chance did you lie in the Seine Mouth!"

"True, thrall; I can swear to that," answered Hroar, and he laughed. "Be certain I would not risk King Sigfrid's longships thus far south without sure gain. It is no harm to speak truth to a man who is doomed,--dead men tell no tales. May you have joy of your answer!"

"I laugh at death. Now tell me, Dane!"

"Know then, my merry thrall, that tidings of your sailing flew to Nordmannia straight from the hall of your king. Sigfrid had word from Wittikind the Saxon, and he from well-wishers across the Rhine. Not all your king's foes dwell without his borders. Some speak Frankish for mother-tongue--"

"You lie! No Frank is traitor."

Hroar only laughed and answered jeeringly: "Maybe a little bird told how Earl Roland should sail south from the Seine with the Frank king's daughter,--a little bird in Frankish plumage. He sang a golden song for me. Your ship rides deep with her cargo, and Frisian thralls fetch a good price at the Gardariki fair.--But I would see your princess. If she is young and comely, I may have other use for her than to grind meal."

At the brutal words, fury seized upon Roland. His eyes blazed, and rage lent sudden strength to his tottering frame.

"Heathen dog!" he gasped; "never shall your eyes look on Rothada!"

Before Hroar could guard or leap aside, the Frank's sword swung overhead and whirled down upon his helmet like a sledge. Had the casque been of common make, Hroar would have met his fate on the spot. As it was, the blow beat a great dint in the gilded steel and sent the sea-king reeling backward, stunned and blinded. A dozen vikings sprang between to shield him, but Roland's sword dropped at their feet. Faint from loss of blood, and utterly spent by that last great blow, the count swayed forward. Darkness shut out from him the ring of shouting heathen. He fell swooning upon the heap of corpses.

"A champion! a champion! The Frank has won his freedom!" cried the vikings, and they pressed about to raise the fallen warrior. Heedless of their own wounds, they sought to bind up his injuries. Their warlike but generous natures yielded homage to the hero who had met overwhelming odds without dismay and had struck a berserk blow even when falling. They forgot the boasted cruelty of their leader.

Never before had the sea-king suffered such a helmet stroke. For several moments he stood dazed, blinking at the stars which flashed before his eyes, while his head hummed like a kettle. Then his vision cleared, and he saw what his men were about. Into their midst he sprang, gnashing his teeth like a wolf.

"Aside, dogs!" he yelled. "Give me my thrall. I will tear out his lying tongue!"

The Danes gave back before the threatening dagger of their chief, and he sprang upon his victim with a yell of triumph. The Frank should pay dearly for that blow!

Some of the milder vikings muttered against the deed. This Frank was no whining coward, no low-born outlander, but a fair-haired hero, such as the Sigurds and Beowulfs of the olden days.

At the best, the Danes bore little love for the cruel Jutland champion whom King Sigfrid had set over them. So now they murmured openly. But Hroar was no less fearless than he was cruel. Regardless of their protests, he turned the fallen Frank upon his back. No wolf ever fell upon his prey with fiercer greed.

Already he had set about his deed, when a cry of surprise from his followers caused him to look up. The crowd had opened, and through the midst of the warriors came a little child-maid, the like of whom the brutal Dane had never seen. Utterly lost to self in her fear for her kinsman, the girl advanced with outstretched arms, her tender eyes full of reproach, her pure young face aglow with spiritual light. Had she been Skuld, youngest of the Norns, the Dane could not have been more astonished. He glared at the child in dull wonder. Could this be Freya's maid,--Gifion, Goddess of Innocence and Maidenhood? At the thought, he started back, a superstitious dread clutching at his heart. But when the first shock of surprise had passed, he perceived the Frankish fashion of the girl's double tunic and the circlet that marked her rank.

"Spawn of Loki!" he snarled. "It's only the Frank king's daughter."

"I am Rothada, and Karl the King is my father," said the girl, with simple dignity. "Are you not the Dane count?"

Hroar scowled assent.

"Speak," he said.

The girl's courage began to falter before the ferocity of the sea-king's stare, and, shuddering, she gazed about her at the heaps of dead and wounded warriors. But she saw friendly looks upon many of the viking faces, and forgot her fears once more in the thought of her fellow-captives.

"I come to offer ransom," she said,--"wergild for all who yet live. My father will pay for every one,--Frank and Frisian alike."

"Doubtless!" sneered Hroar. "But we will talk of that in Nordmannia before King Sigfrid. Wittikind may have a word to say in the matter. One thrall at least I keep as my share of the loot. Stand aside while I put my mark on him."

For the second time the Dane turned to his victim. But Rothada was quicker than he. With a piteous cry for mercy, she flung herself upon Roland and sought to shield him from the knife with her own slender body. The sight would have melted any heart that held the slightest trace of nobleness. It stirred the vikings to open mutiny. They renewed their protests, with deeper menace in their tones, and when Hroar bent and grasped the maiden roughly by the shoulder, one of the foremost swung up his sword.

"Stay, Hroar!" he commanded. "I am not used to looking on at foul deeds. You must first pluck out my eyes before you take the Frank's tongue."

"Ay, and mine!" growled a second viking.

Hroar stood erect and glared at the daring men. But neither gave way before his terrible look. They had the backing of their fellows. The sea-king saw this, yet his hand went to the hilt of his heavy sword. The fight was averted, none too soon, by a scarred old berserk.

"Bear wisdom to Urd!" he called scoffingly. "Hroar bickers with his wolves, while the Norse hawks swoop upon him."

At the warning, every Dane aboard the trade-ship wheeled about and stared seaward. The harsh alarm of a war-horn, braying over the water, was not needed to explain the situation. A bowshot away they saw their second longship surging at full speed up the estuary. A fountain of white spray spouted from under its forefoot, and the boiling sea alongside, threshed to foam by the oar-blades, told that every bench was full, every rower pulling to the utmost of his strength. Not without cause! Close in the Dane's wake the three longships of the outer estuary came gliding over the water in swift pursuit. Each lay far over under the pressure of its great square sail, and from the mail-clad crews packed along the fighting gangway behind the weather bulwarks, rose jeers and grim laughter at the efforts of the Danes to escape.

"Norse!" shouted Hroar. "Thor! they mean to attack us! Aboard ship and man the oars--yet stay! First scuttle the trader. We leave no booty for the fiordmen!"

"They strike sail!" cried the old berserk. "Wait a little. They do not swing the red shield. It may be a jest."

"A bitter jest-- Ho! the foremost comes on alone. Aboard ship, all, and stand ready to cast off. I wait the Norse earl here."

CHAPTER III

At the alarm of the Danes, the trembling heart of the little princess leaped with joy. But the sudden hope gave way as quickly to renewed terror. Why should the cruel sea-count linger on the trade-ship alone if not to carry out his ferocious revenge? Closer than ever the girl clasped the senseless warrior in her arms, until the blood from his wounded head seeped warm through her silken kirtle, and the bell-like rim of his helmet bruised her tender bosom.

Breathless, she listened to the rush and outcry of the vikings as with their wounded fellows they poured back into the longship. Then, in the lull which followed, she could hear the smothered wail of her tiring-woman, crouched in the cubby beneath her. Gaining courage from the silence, she at last ventured to raise her head. She saw Hroar at the farther bulwark, gazing intently down the estuary. He did not move, and Rothada rose timidly to look around.

The second Dane ship was coming about only a few yards astern; but its crew, like the crew of its consort, were far too intent on watching the Norse ship to give heed to the little maiden. Even the Frisian sailors had ceased to cower, and were lined along the bulwarks forward, full of eager hope that the approaching longship might bring them a change of masters. Hroar's cruelty was only too well known throughout Frisia.

Rothada also gazed at the stately prow of the stranger and joined in the longing of her fellow-captives that the new-comers would seize the trade-ship for their own. But the little maiden's faith gave her still fairer hopes than those cherished by the Frisians. To her girlish innocence, deliverance now seemed certain. She had only to appeal to the Norse count, and he would accept ransom for all. Tears of gratitude shone in her violet eyes as she stooped to bind up with deft fingers such of Roland's wounds as the Danes had failed to stanch.

Her task ended, the girl started up again to gaze over into the Norse ship as it glided alongside. The vessel swarmed with huge warriors, whose superiority to the Danes both in discipline and armor was so striking that even the convent-bred maiden could not but perceive the difference. Against such men, even had the odds been reversed, the Danes could not have hoped to hold their own.

When Rothada comprehended this, she clasped her hands in joy and looked eagerly about for the Norse leader. A small blue banner, emblazoned with a gold star, fluttered on the longship's stern, and Rothada's first thought was that the blond viking at the helm beneath it must be the sea-king. But then, standing alone in the vessel's prow, she saw a warrior whom even she could not but recognize as the Norse leader. His round casque, though wingless, was of blue steel and rimmed with a gold band in whose front sparkled a garnet star. Even more beautiful was the young sea-king's serk, or coat, of ring-mail, which shimmered in the sun like ice. His small round shield differed from the usual Norse and Frankish patterns both in the greater convexity of its shape and in the material of its face,--a disc of hammered steel. Its bluish surface, polished like a mirror, was traced with gold damascening both on the boss and on the thickened rim.

Yet with all the young sea-king's splendid war-gear, so slight and boyish did he appear in contrast to his followers that Rothada at first thought he could be little older than herself. But when he stepped forward and answered Hroar's hail, it was with a haughtiness of tone and bearing far other than childlike.

Even as he spoke, the Northman sprang upon the bulwark of his ship and, great as was the distance which yet separated the vessels, leaped for the trade-ship's deck. With a cry of astonishment, Hroar sprang sideways from before him, down upon the smooth surface of the bales of goods in the after hold; while high above the water the leaper's bright figure flashed through the air and shot in over the bulwark. Lightly as a panther, the Northman struck the deck and turned instantly to confront the Dane. But Hroar stood motionless, overcome with wonder at the daring leap, and did not seek to regain the deck.

Seeing that there was no danger of immediate attack, the Northman lowered his shield and looked about with keen glances at the slaughtered Franks and Danes.

"Thor!" he cried, "these Rhinemen fought well. Would that I had led the heroes! But what's this?--a Frank yet alive, and beside him a child-maid!"

Now entirely heedless of the Danish sea-king, the Northman advanced to stare at the forlorn survivors of Hroar's attack. Had Rothada possessed her cousin's knowledge of men and customs, she would have stared back at the sea-king in bewilderment. The haughty face which so coldly confronted her was dark and oval, with arched nose, lofty brow, and black eyes of intense brightness,--features part Arab, part Greek in character, but in no respect Norse. Yet the young chief's hair proved quite as fully that his leadership must be founded on kingly Norse blood. It was of silky fineness and curled down beneath his helmet rim in locks like burnished red gold. His dress also was that of a king's son. The cloak of sable, clasped by a jewelled brooch, was lined with cloth of gold, while money-rings coiled their yellow spirals around the ring-mail sleeves which extended to his wrists.

Abashed by the extreme brightness of the sea-king's gaze, Rothada lowered her admiring eyes to the splendid recurved sword which swung at his belt. Roland could have told her that the weapon was a sword of the Saracen folk,--a Damascus blade, which would bend to the hilt without snapping and, like the Wrath of Sigurd, cut alike through iron bars and floating wool. With the peace-thongs knotted, even that far-famed blade of Regin's forging could not have compared with this magnificent weapon, whose sheath sparkled with gems, and upon whose pommel blazed the splendor of a priceless ruby.

The glint of gold and jewels recalled to Rothada's mind her own high rank, and gave her courage to glance up again. At sight of the milder light in the dark eyes of the sea-king, she raised her arms to him appealingly.

"Bright count of the sea!" she cried, "the dear Christ has sent you to save us. The cruel Dane's knife shall not harm my kinsman!"

The Northman glanced down at the wounded Frank.

"Who is this warrior?" he demanded.

"My kinsman, Count Roland. He is a high lord of King Karl, my father--"

"Your father,--the Frank king!" cried the Northman, and his eyes flashed a look at the girl that made her tremble. But again their keenness softened, and he pointed to her bosom.

"There's blood upon your kirtle," he muttered. "Do these Danes war upon babes and bairns?"

"It is my kinsman's blood. The Dane count would have harmed him as he lay helpless. I tried to shield him."

"Bravely done, little maiden! Though twice over the daughter of King Karl, the deed shall count you good weight in the balance. Take heart! Not all vikings are swine. Olvir Thorbiornson does not war upon maids and stricken heroes. Now I go to settle with this Dane boar who rends fallen foes."

"It is time to cease prattle," Hroar called up jeeringly. "Come, talk with a warrior. What says the bairn with outland face? Will he meet a sea-king singly in sword-play, and stake the trade-ship as prize?"

At the challenge a strange smile lit up the Northman's dark face; but he replied gravely: "A shrewd bargain, Dane! You would have me fight for what I need only reach out my hand to take. First tell me your name."

"You 're late from your mother's bower, bairn. Few vikings ask the name of Hroar the Cruel."

"Hroar! Hroar the Cruel!" repeated the Northman, in a smothered voice. His hand closed on the hilt of his sword, and his face went white with anger. Had Hroar seen the look in his eyes, he would not have grinned at his pallor or at the soft lisping voice in which the Northman answered: "Go, bid your other ship make fast. All craft shall lie quiet while I make an end of Hroar the Cruel."

The Dane laughed derisively, yet turned to repeat to his own crew the command which the Northman shouted over the opposite bulwark. Soon all six ships were drifting abreast on the stream,--the two Danes on one side of the trader, the three Norse craft on the other. The Danish crews kept warily aboard their ships, ready either for fight or flight. But as the first Norse ship grappled, from its prow a blond young giant leaped, axe in hand, sheer over Hroar's head, and down upon the cargo beyond him.

"Loki!" cried Hroar, starting back. "Erling Fairhair! The dead come to life!"

"Your guilt stings you, murderer," rejoined Olvir. "This is only Liutrad, son of Erling--but he bears his father's axe; and now comes one--"

"Ha, Floki--Floki the Crane!" gasped Hroar; and he glared like a trapped wolf at the strange viking who sprang down over the bulwark after young Liutrad. Though little broader than his fellow-Northmen, the man towered up a good span above seven feet in height, and the long-shafted halberd which he bore on his shoulder did not tend to lessen the effect of his giant stature.

At sight of the Dane chief a ferocious smile distorted the wry face of the giant, and he bent to him mockingly.

"Heya, old shipmate!" he croaked. "Many winters have sped since we parted on the Rhine bank."

Hroar licked his dry lips and answered thickly: "Those were good old days when we followed Thorbiorn and Otkar over sea and land. I call to mind the loot of Kars, when Thorbiorn bore off the emir's daughter for bride. You were not so mean in those days as to sail under a boy whose outland swartness--"

"--Proves the blood of the emir's daughter."

"How!--this elf the son of Thorbiorn Viking?"

"Ay," murmured Olvir; "the son of the lord you betrayed. Ho, Danes! now shall the murderer pay his blood-debt. Many times I have harried your dune coasts in search of this foul traitor, who, one and twenty winters gone, sold his sword-fellows and his earl into the ambush of the boy Karl."

"That is a lie!" shouted Hroar. "Only to save my own life--"

"Be still!" commanded Olvir. "The Crane shall bear witness for me. State the charge, Floki."

The lofty Northman stepped upon a cask, and his grey eyes swept their gaze over the Danish ships and back to the Danish sea-king, cold and hard as steel.

"Hearken, Danes," he began in a dry croak; "Floki the Crane is not given to lying. He can strike his bill straight to the mark, and his tongue thrusts as straight. Doubtless this murderer has told you how in days gone by Thorbiorn Viking fell in the Frankish ambush on Rhine Stream. I, too, was there. Like the earl, I was struck down by the Frankish spears. I saw the boy Karl rush out upon our fallen leader; then a war-hammer stretched me witless. When I saw again, before me stood the traitor Hroar. In his hand was the sword of his lord, and he was making blood-play of his own shipmate, Hauk Otterson, whom men called Longarm. When Hauk was dead, his slayer came to me. He was minded first to cut off my feet, because, as he said, I was too tall. But then came the son of Pepin, and, casting at the traitor the gold for which he had sold his fellows, bade him begone from Frank Land. When, after many years, I broke from the Frankish thrall-bonds, I searched long and fruitlessly for the murderer. He had hid his shame in the Saxon forests."

"He lies--the croaking stork lies! There is no proof!" cried Hroar, loudly; but his eyes fell before the look of his grim accuser, and glanced uneasily over the bloody deck, until a dry chuckle from Floki stung him out of his caution.

"At the least, you will grant that the charge is somewhat stale," he sneered.

"The fouler the deed's stench," retorted Floki, thrusting forward his sharp face with a look of deadly menace. "We have run you down at last, coward, and you shall pay your share of the blood-debt. Hearken, Danes! The viking's son is not hunting this boar alone; he hunts bigger game! When I, hopeless of finding the traitor singly, after many winters fared home to Trondheim to gain aid, I found this unknown son of Thorbiorn dwelling outlaw in Starkad's grave-mound with Otkar, his foster-father. Since then each season we have scoured your dune coasts for the traitor. But the great wielder of Starkad's axe set foot on the trail of mightier game. Who of the North has not heard how, in the hall of King Carloman the Frank, and in the realm of Desiderius the Lombard, Otkar Jotuntop, wisest and strongest of warriors, fought and plotted against King Karl with all the craft of his wit and lore and the terror of his axe? Yet the grey bear failed to wreak vengeance against Thorbiorn's slayer, and his ashes lie in Starkad's mound. But here above me stands his bright fosterling, and when Olvir Thorbiornson has slain Hroar the traitor, he shall sail on to bring to an end the task of Otkar."

"Otkar--Otkar!" echoed a feeble voice. "Who speaks of the Dane hero?"

As the viking leaders wheeled about in surprise, Roland, aided by Rothada, sat up and stared at them with dazed eyes.

"The Frank earl!" muttered Olvir. "You 've heard of him, Floki,--Count Roland, the Frank king's kinsman."

"Ay, ring-breaker; I remember how, when he returned, Otkar spoke much of this brave Frank."

"Even when he lay dying--"

"Saint Michael! he is not dead,---Otkar the Dane, who, all but single-handed, cut his way from Pavia through the thick of our host! I stood in his battle-path, thinking, in my boyish folly, to check the rush of the grey bear. But he was high-minded; he struck with the flat. Would that he had not fled to the Greeks! When the king saw his battle-path, he swore to make him Count of the Saxon Mark."

"How! Otkar his foe?" exclaimed Olvir.

The Frank stared up at him and nodded faintly as he sank back upon the heap of bodies. The Northman gazed back at him for a little with a puzzled look. But an impatient growl from Hroar recalled his attention to the Dane.

"Hark, my Frank hero," he said; "we will talk of this later. Now my sword sings the death of Hroar the betrayer. Run, maiden; fetch drink for the hero, that he may have strength to watch the sword-game."

"So the laggard at last draws sword," sneered Hroar. "He has had his pleasure; now I claim mine. Ironbiter thirsts; yet before he tastes the warm blood the pledge of the fight shall be made known. Speak out, bairn! If I win I go hence with trade-ship and all, unhindered,--let the charge against me be what it may."

"Such are the terms,--all men bear witness!"

A grin of cunning triumph broadened the Dane's ferocious face.

"Then now is Hroar ready," he called loudly. "Now will Ironbiter split the skull of this base-born changeling as it split the skull of the man he calls father."

A terrible oath burst from the lips of Floki; but Olvir silenced him with a look. Then, white to the lips, the young sea-king turned again to his enemy.

"Dare you repeat that lie?" he asked in the soft lisp that betrayed to his steersmen how deadly was his anger.

"So the bairn begins to quake," jeered the Dane, deceived by the Northman's seeming mildness. "Even so quaked that braggart Thorbiorn when I swung Ironbiter his own sword above his head."

"That is a double lie," rejoined Olvir, in the same quiet voice. "If you met Thorbiorn, son of Starkad, in battle, it was not he who quaked. Nor did you slay the hero. When he lay dying, pierced by the darts of hidden foes, the boy Karl ran from behind and thrust him in the back. Floki is no liar."

"No, by Odin," boasted Hroar. "Floki did not see all. Pepin's son sought to stay me when I ran to end the snared wolf. Would that I had broken the back of the meddlesome bairn! Floki has told how he drove me from his camp before I was half done my play with the thralls."

"Enough, murderer!" cried Olvir. "Now are you doomed; look on your bane!"

With the words, the young sea-king's hand gripped the hilt of his curved sword. The blade flashed from its sheath like a tongue of blue flame. Proudly its wielder held the weapon up before him and gazed at the play of iridescent light on its mirror surface.

"Al-hatif, the Priceless! the Beautiful!" he half whispered. Then suddenly his black eyes flamed with a terrible joy. He flung off his cloak and leaped down before Hroar, whirling the blade about his head.

"Come, Dane! come, coward!" he shouted. "Long have I sought you. Come to the serpent's kiss! come to your bane! Hel's blue hand outstretches; Fenir shall rend you!"

At the biting taunts the Dane's massive figure quivered with passion, and all the malevolence of his nature showed in his brutal face. Up swung his ponderous sword, and he advanced upon his foe like an aurochs bull.

"Leap, bairn!" he yelled. "Ironbiter swings; he will split your swart face!"

But the Northman did not leap.

"Strike and see," he called tauntingly.

Even more scornful than his words was the Northman's bearing as he lowered his sword and stood with the little shield raised overhead. To thus set himself in the way of his huge opponent seemed little short of madness alike to the Danish vikings and to Roland. The Frank could not restrain a groan of despair, while Rothada, darting back to his side with a flask of wine, cried out in terror. Already the great sword whirled overhead to cut down their champion.

A glance at the Norse steersmen might have reassured the captives. The blond young giant and his lofty companion were waiting the outcome of Hroar's attack no less calmly than their slender leader. Cool and quiet, Olvir faced the savage Dane, his lip curled in a haughty smile; but his eyes glittered like an angry snake's. Stung by the scorn of the smile, Hroar put all his strength into the sweep of his sword.

"Thor aid!" he roared, and the sword whirled down with terrific force. But the Northman only smiled the more scornfully and caught the blow on his tilted shield with such consummate skill that the blade glanced harmlessly aside from the steel surface.

A deafening uproar greeted the feat, the Danes on the one side crying out their wonder, while the Northmen across answered with shouts of triumph. The noise ceased as abruptly as it burst out. Olvir had raised his curved sword and tapped the hauberk of the Dane in warning. Had he wished it, he could have slain his enemy then; for Hroar was so astonished by the turning of the blow that he stood with lowered shield.

"Ward yourself, Dane!" cried the Northman; and as Hroar started back, the Damascus sword began to dart forward like the beak of a striking heron. Up whirled Ironbiter for a second stroke; but Olvir did not wait its fall. With a wild cry he hurled himself upon the Dane like a maddened wolf. Above, below, on all sides, his sword flashed around Hroar's shield in thrusts so swift that no eye could follow. In vain Hroar sought to cut down with sweeping strokes the bright figure that leaped in upon him till the two shields clashed; in vain he sought to avoid the lightning sword-thrusts that dazzled his eyes.

Bleeding from a dozen stabs, his shield-arm pierced and cheek laid open, the ferocious Dane drew back appalled. His glaring eyes no longer saw a human foe before him; that shimmering, leaping figure was Thor, the Danish Thor, terrible in his youth and beauty.

Step by step the Dane retreated, until his back struck the bulwark. The touch spurred him to desperate fury. But he sprang forward, only to reel back again before the stabs of the pitiless sword. The end was now come. Half dazed, he dropped his shield to meet a leg feint, and the blade lunged through his unguarded neck, so that the point stood out a span behind.

CHAPTER IV

On the picturesque Garonne bank, beneath the Roman walls of Casseneuil, lay the camp of the Frankish host. Since Easter the levies of blue-eyed Allemanni and dark-eyed Aquitanians and Bretons had been pouring in to swell the ranks.

For a mile around, the fertile hills were dotted with tents and booths. Overhead stretched a canopy of blue haze, the smoke of the countless fires. Long lines of ox-wains trailed in from all parts of the land; great droves of cattle browsed in the meadows; and water craft of all sizes sailed to and fro on the Lot and the Garonne, or lay moored along the banks while busy sailors shifted cargo. The larger vessels were from Bordeaux and the sea; others plied between Casseneuil and Toulouse, where a smaller host--Burgundians and Lombards, and the Goths and Gallo-Romans of Septimania and Provincia--were being mustered by Barnard, the king's uncle, to invade the Saracen country by way of Narbonne. The grandson of Karl the Hammer was gathering his might to strike the pagans such another blow as had shattered their host on the plains of Touraine.

The royal pavilion stood in the heart of the camp, close to the river's bank. Above its peak floated the gold-bright folds of the three-forked standard, and the scores of messengers that came and went told that Karl the King was busied with the affairs of his vast realm. Those who passed in saw first a striking assemblage of the king's liegemen,--long-robed priests, counts in full war-gear, and court officials, ornate with silks and jewels. Here were warriors who had seen the fall of Pavia and helped to hew down the Irminsul; bishops and abbots who ruled ecclesiastical estates, the revenues of which were little less than princely; missi dominici,--those trusty liegemen who bore the king's will to outland lords, or journeyed through their appointed ridings to bring justice for all against the petty tyrannies of count and bishop and judge.

Yet though the pavilion held within it many of the most famous men of the greatest realm since the fall of the Western Empire, the new-comer would have been certain to pass by all alike with a hasty glance and turn half reverently to the low dais where Karl the King sat on his oaken throne. Aside from his jewelled sword-belt, there was little of gold or gems about the massive figure; but beneath the sapphires and holy nail of the Lombard crown the grey eyes of the great Frank gazed out with calm power. War-counts and priests alike bowed before that glance; for in mind, as in body, Karl was master of them all.

The last of the missi called into service had been despatched to inspect the four quarters of the realm, and the king was now in earnest consultation with two Moslem envoys. The contrast between the lean figure and patriarchal beard of the older Saracen and the blond, massive-limbed Frank was as great as that between the king's jerkin and cross-thonged stockings and the envoy's green turban and flowing white burnous. Yet such of the bystanders as were accustomed to look beneath mere outward appearance saw in the Arab sheik's dark face an expression strikingly like that which gave such dignity to the fresh ruddy countenance of the king. Not all the wide difference in race and dress and years could hide the stamp of power with which Nature had marked the features of the two.

The other Saracen, who, like the king, appeared to be scarcely three or four years past thirty, showed warrior training in every pose and feature; but a covert sneer lurked beneath his impassive smile, and from eyes that blinked like those of a bird of prey he shot quick, evil glances at the surrounding Franks.

Presently there entered the pavilion a thick-set, tow-haired warrior, with red, beer-bloated features, who jostled his way to the front without wasting breath in apologies for his rudeness. As he approached the dais the younger Saracen glanced at him, and, with a seemingly careless gesture, touched the hilt of his scimetar. He turned away at once to join in the parting salaams to the king, while the boorish warrior returned to the pavilion's entrance. As he came to a halt near the Grand Doorward, he pointed outside, his low forehead creased in a savage scowl.

"Here comes the duke now, and in choice company," he grumbled. "The Merwing shall learn that Rudulf's daughter is not for a Vascon, though he be twice over the rightful heir of Clovis."

"Does Count Hardrat speak of the Vascon Wolf?" inquired the doorward, half heeding.

"Vascon fox!" rejoined Hardrat. The jest seemed to ease his ill-humor, and he turned his gaze to the duke's beautiful companion.

The girl was young,--certainly not more than seventeen,--but of all the queen's maidens, none could lay claim to so many suitors. Among her own people and the other blond Germans beyond the Rhine she would have been considered too dark for perfect beauty; but, North Rhine or South Rhine, few men could have looked at her without a quickened pulse-beat. There was allurement in every line of her softly moulded features, in the rich bloom of her olive cheeks, and in the silky meshes of her gold-brown hair. Envious rivals might say that her eyes were over-narrow for beauty, and her lips of too vivid a scarlet. None the less, the ardent warriors and courtiers, and more than one mitred churchman, longed for the kiss of that enticing mouth, and willingly gave themselves over to the spell of the bewitching eyes with their strangely shifting tints of blue and green.

Such was Fastrada, the daughter of Count Rudulf, youngest, fairest, and most sought for among the queen's bower-maidens.

It was not to be wondered, therefore, that as he strolled with her up to the pavilion Duke Lupus kept his small eyes fixed upon the girl in an amorous stare. Near the entrance he paused and sighed regretfully.

"Here is the king's tent, maiden," he said. "I wish it had been more distant. At your side the way was all too short. I am more than repaid that I left my horse at the villa gate for my suite to bring after."

The girl looked up, open-eyed, into the Vascon's sensual face, and replied with a simplicity that to a casual observer would have appeared almost naive: "The noble Lupus has done me great honor by his escort. Our gracious queen will not soon forget such a favor."

"And the queen's most charming maiden--?"

Fastrada bent her head to hide a smile, but her voice was very soft: "Who could forget a kindness from the Duke of the Vascons,--from the rightful heir of Clovis?"

Lupus started, and glanced hastily before him into the pavilion. He had often boasted of his descent from that long line of lustful, bloody, indolent Merwing kings, the last of whom had been deposed and his crown seized by Pepin the Short; but all of those boasts had been uttered when the usurper's son held court on the farther side of Aquitania. His relief was heartfelt when he perceived that only one other than himself had heard the dangerous compliment. Hardrat met his furtive glance with a meaning smile and came forward to bow before Fastrada.

"Saints grant I may be of service to our dame's fairest maiden," he said.

The girl lowered her eyes demurely.

"I bear a message to our lord king," she replied.

"Then the Christian maiden must wait for heathen dogs."

Fastrada looked up at her two suitors with an arch smile, but only Lupus perceived the trace of malice that lurked in the corners of the scarlet lips.

"Do not be angry for me, Count Hardrat," she said. "It is a pleasure to wait in company such as that with which I am favored."

Both lords smiled at the flattery; but while the duke repaid the compliment in graceful phrases, Hardrat glared at his rival with jealous suspicion. From beneath her modestly drooping lashes Fastrada watched how the Thuringian's brow lowered under the arrogant stare of the duke. Her pulse quickened, and the shifting tints deepened in her downcast eyes. But the war-count checked his threatened outburst, and so put an end to the sport.

Petulantly the girl turned to the entrance, only to look about in appeal to the Vascon.

"Ai, lord duke," she exclaimed; "who are these heathen? I can see only their strange headgear."

"They are Saracen counts, the pagan allies of our Most Christian King," answered Hardrat, and he smiled ironically. "But look,--their audience comes to an end. I can now lead you in before his Majesty."

"I give thanks," murmured Fastrada, but her eyes were fixed upon the envoys. The officials near the entrance had drawn apart, and the white-robed Saracens, having salaamed themselves to a respectful distance from the dais of the mighty Afranj sultan, were completing their exit in a more dignified manner. The tall leader came out like a veritable Sheik el Islam, his firm tread, erect frame, and eagle glance giving the lie to the whiteness of his hair and flowing beard.

Fastrada slipped in front for a closer view of the grand old warrior, but was met by the leering gaze of the younger envoy behind him. Before his stare the girl shrank back, blushing with offended pride. Yet she looked eagerly around after the Saracen leader, and her changeful eyes sparkled as she exclaimed: "There goes a hero! Would that he were young! We 'd see a warrior such as few Franks could withstand."

"Strange words for a daughter of Thuringia," replied Lupus; "yet, none the less, they are very fitting. Al Arabi is a count of great fame among his people. He has held many high offices, and though no longer Count of Saragossa, he is friend and chief councillor of Al Huseyn, the vali who succeeded him. Old as he is, even now he can strike a heavy blow."

"He is a raven-feeder!" growled Count Hardrat. "Nor is Vali Kasim a babe. The old man has a stout son-in-law. Also, he owns a silent tongue and does not bicker with his friends. Come now, maiden, if you would see the king."

The girl smiled, and bowed both to Lupus and to her red-faced countryman. Then, with hands clasped before her and eyes demurely downcast, she followed the latter through the brilliant assemblage to the royal presence. Karl, though dictating a memorandum to Abbot Fulrad, the white-haired Keeper of the Great Seal, paused at once and nodded pleasantly to Hardrat.

"You bring a maiden from Hildegarde," he observed in a voice clear and strong but strangely shrill for so massive a body. "I am mistaken if it is not the daughter of our faithful Rudulf. I trust that she bears good tidings."

Fastrada bowed low before the dais. "Our gracious dame bade me bring word to your Majesty that her pain has eased. She enjoys good health again, though she put away the leech's drugs."

"As well--as well! I 'd wager a little fasting against the best of leeches. But, indeed, these are good tidings, and they come by the mouth of a fair emissary," replied Karl, his gaze lingering on the soft beauty of the girl's face and form. "It is a dusty path to the gates, and the herald of our queen should be spared the pains of walking it twice in a day. Let her delay her return. There will be a seat in our barge when we go to the noon-meal."

Fastrada bowed and withdrew, half awed, into the midst of the assemblage. Yet the admiration in the king's glance had by no means escaped her. Her cheeks glowed with pride at thought of the look and of his kindly tone. After royalty, the homage of lesser men lacked flavor, and the girl listened to the eager greetings of the court officials with an indifferent bearing. Of what value the blandishments of these sleek courtiers and petty counts when heroes such as the famous Roland and Hardrat were no less eager for her favor? And now the king himself had looked at her with far other than a cold eye, though Queen Hildegarde was yet held to be the most beautiful woman in the realm.

With true feminine perversity, the girl turned from all others and set about the task of pleasing a lank, dour-faced official, the only one in the pavilion who seemed altogether indifferent to her charms. The man met her advances with a sardonic smile, and gave a curt response to her greeting; while his pale-blue eyes turned away from her soft beauty to fix their cold stare on the approaching figure of Duke Lupus.

"The Merwing is ill named," he muttered in his beard, struck by the same thought that had prompted Hardrat's jest. "He should be called Fox, not Wolf,--a cunning fox! He will bear watching."

"What is my Lord Anselm pleased to say?" asked Fastrada. "He has the look which he wears when he sits on the judgment-seat, dooming the luckless offenders."

"Maidens should chatter and spin, and leave weightier matters to those who have wit," answered the judge, dryly.

"Alas, then, for the maidens, if all men agree with the Count of the Palace!" sighed Fastrada; and she drew back in mock sorrow.

Anselm paid no heed to the alluring play. His attention was fixed upon the Duke of the Vascons.

Lupus advanced with an arrogance that won him little favor among the proud Franks. But Karl smiled, and even extended his hand for the salute when the duke would have bent to kiss his knee.

"With joy we see again our faithful friend," he said. "Not satisfied with swearing allegiance the second time, he brings us needed supplies with a bountiful hand. It is well this fair Southland is held for us by so trusty a liegeman."

"My lord king is pleased to be gracious," replied Lupus, quickly. "If I have won his indulgence, I now beg leave to ask a favor."

"Speak. Anything I can rightfully give shall be allowed you."

"It is no small matter, your Majesty; the insolent Bishop of Rome has stricken the mitre from the head of my kinsman Thierry."

Karl started and frowned.

"Alter your asking, lord duke," he answered. "I cannot set aside so just a judgment. There were charges and a fair trial for the Bishop of Bordeaux. He has failed to clear himself on a single count; drunkenness, strife, licentiousness,--all were proved."

"Slander, sire!--malicious slander!" cried the duke, his passion overleaping all caution. "My kinsman is persecuted for his lineage! Few priests of his rank but wassail and brawl unrebuked. As for the third charge, strangest of all in a realm whose king--"

"Silence!" roared Karl; and he towered up on the dais like an angry lion. "Has the kinsman of Hunold and Waifre twice sworn allegiance to doubt the justice of his king and Holy Church? I, the king, sent Pope Hadrian command for the trial. It is enough that dukes and counts trample the common folk and wallow in the troughs of their sodden vices. At the least, I will scourge the swine from God's Church. By the King of Heaven! when I have swept the pagan Saracens into the sea I will cleanse the household of my kingdom,--from duke to deacon! Thierry has lost his mitre; let him repent and walk upright, lest worse come upon him."

Stunned, humiliated, livid with impotent anger, the haughty Merwing shrank back from before the son of Pepin, and hastened to quit the assemblage that had witnessed his shame. Most of the Franks met his black glances with ready frowns; but Hardrat, the Thuringian count, could not conceal his pleasure at the turn of events.

"All goes well!" he chuckled. "The fox is shrewdly nipped. He 'll stop at nothing now. Rage will melt all his frosty caution. The others are with us, heart and hand, and that missive to Saxon Land by this time should have rid us--"

The conclusion of the Thuringian's half-muttered words was lost in a terrific blare of trumpets and war-horns that sent the alarm ringing to every corner of the Frankish camp.

Within the pavilion all was instantly struggle and confusion. Swords flashed overhead, and the assemblage surged from side to side as the war-counts sought to push out from the press of officials and priests. But Karl the King walked swiftly through the parting crowd, his face serene, his sword unsheathed. The warriors rushed after him, weapon in hand.

CHAPTER V

Most women at such a time would have cowered behind the empty throne; Fastrada sought to pass out with the war-counts. She was caught, however, in the press which closed behind them, and even with Abbot Fulrad's aid could not gain the entrance for some time. When at last the sturdy old Keeper of the Seal drew her into the open, the horns had ceased braying, and a strange hush lay upon the camp. But the river-banks were lined with armed men, and Fastrada saw hundreds of other warriors running to join them.

"What can it mean?" she exclaimed. "Have the Aquitanians revolted? Look how every man stares down the river."

"Let us go yonder to the knoll where the king stands. There the view is clear," suggested Fulrad.

"I see masts already,--five of them," exclaimed Fastrada, as they hurried forward. "Each bears a white shield at its peak. It cannot be they are Greek ships. They must be Frisian traders, or an embassy from Alfwold, King of Northumbria."

"Neither one nor the other, maiden," rejoined Fulrad. "Years since, in the days of Pepin, I saw the like,--once upon the Seine, and again upon the Rhine, in the Frisian Mark. It was there Karl fought his first battle,--a lad of twelve."

"But these ships--of what land are they? See how stately they surge up the river with their glittering prows; and hark to the oar-song of their crews,--a lay of the old gods! I 've heard it in the forest when no priest was near."

"Ay, maiden; these are heathen craft, and they bear warriors more terrible than the Saxon wolves. You've heard of Lord Otkar. These are his countrymen."

"Danes?"

"Truly; from Sigfrid's realm, or from Jutland, which is beyond. Otkar was of a land yet more distant. He told me much of the Norse folk; of their great wealth and fierce war-spirit. God grant that Wittikind the Westphalian lies quiet in Nordmannia and does not march back with the host of his wife's brother. The Saxons and Frisians are hard enough nuts to crack, without the Danes."

"But how come these heathen on the Garonne?"

"We shall soon learn," answered the abbot, pointing with his staff. "Here is the first ship abreast. Mark the mail-clad crew."

"The ship turns," observed Fastrada.

"And the others follow. They will moor before the king."

Even as Fulrad spoke, the oars of the longships rattled inboard, and the five beautiful craft glided toward the bank. They might have been dragons wheeling in salute to the royal standard. Spellbound by the sight, warriors and courtiers and king alike stood silently waiting while the stately prows swept inshore. First the leader and then, in quick succession, the four others ran aground, and the hush was broken by the thud of grapnels cast upon the bank. As the sterns of the vessels swung downstream with the current, a gangplank was thrust ashore from the prow of the leader.

The first to leap down the plank was a gallant young warrior in Frankish armor, at sight of whom the king cried out in astonishment: "Gerold!--with these Danes!"

"The Northmen come in peace, sire," observed Abbot Fulrad. "If not, how is it the queen's brother bears them company?"

"Peaceful or not, lord abbot," rejoined Hardrat, "these are insolent pagans to sing forbidden lays in the midst of a Christian host. Shall I not take horse, sire, and bring down the galleys from Casseneuil? Look, your Majesty! Count Roland follows Gerold; and he totters from recent wounds!"

But Karl made no answer. He was staring intently at the lithe warrior in shimmering mail who had leaped up to help Roland across the gangway.

"Ho, Fulrad," he called; "look close at the Dane count's war-gear, and call to mind that old Norse bear Otkar. His mail was the same in every point as this bright falcon's. Can they be kinsmen?"

"Old oak and young ash,--they 're little more alike, sire. But the lad will shortly tell us," remarked Fulrad, as Gerold hastened forward.

The queen's brother mounted the knoll, and knelt to kiss the extended hand of the king.

"Greeting, lad! You return in strange fellowship," remarked Karl, his gaze fixed upon the bright Northman, who was supporting Roland up the bank.

"They are shipmates whom I know your Majesty will gladly welcome," replied Gerold, with fervor. "Never have I seen such warriors! I fell in with them at Bordeaux."

"Bordeaux?"

"I journeyed to the Vascon burg from Fronsac, thinking that my lord would wish to know more of the new walls which Duke Lupus is building."

"Well done! But these Danes?"

"I can thank their count for a quick journey! He comes to you on a strange mission-- But let Roland speak, sire. He owes the Northman freedom and life."

"More, sire!--more!" cried Roland, as he sprang forward from the supporting arm of his companion.

The king met him halfway, and drew him up as he sought to kneel.

"You 're wounded, kinsman!" he exclaimed. "You have fought at sea! Where are your followers--and the child?"

"I have lost my henchmen, sire; but all else is well--thanks to Lord Olvir, my noble sword-brother."

"This Dane?"

"Ay, sire; leader of half a thousand sea-wolves,--the pick of the North. He has saved me from torture and the princess from shame."

"By my father's soul, he has earned the good-will of one who can repay! Stand forward, my bright Dane, that Karl the King may give you thanks."

At such a bidding from the lord of half Europe, most men would have run to kneel at the king's feet. Such, however, was not the manner of vikings, and Olvir Thorbiornson was not only a leader of vikings, but, throughout the heathen North, could have laid claim without dispute to a descent direct from Odin. Instead of hastening forward, with glowing face and ready bows, he advanced proudly erect, as one sea-king would meet another.

Karl and his lords gazed at the young heathen in wondering admiration, no less impressed by the grace and pride of his bearing than by his rich dress and the beauty of his sword and war-gear. Beside his lithe figure and dark, masterful face even Gerold of Bussen appeared rough and uncouth.

Olvir neither bowed nor knelt, but raised his shield overhead in salute, and returned Karl's gaze with the unflinching look of an equal. It was a novel meeting for the warrior-king, before whom even the wild Saxons trembled. He frowned and said shortly: "It would seem that the Danes are stiff of knee."

"Then set us in your battle-front, lord king," replied Olvir.

"Well answered!" cried Abbot Fulrad.

"You wish to join my standard, young Dane, and seek the post of danger?" said Karl, now smiling.

"Where else should a king's son stand? For this war the foster-son of Otkar Jotuntop seeks place with his sea-wolves in the fore of your host."

"Otkar the Dane!--you his fosterling?"

"And blood kinsman."

"Where, then, is the hero?"

"His ashes lie in the mound where he reared me."

"Dead?--that giant warrior! But he sent you to make peace with the foe whom without cause he sought so mightily to harm."

"No, by Thor," rejoined Olvir, his black eyes glittering. "To the end Otkar thought only of vengeance. He gave over the task into my hand. I sailed out of the North to harry your coasts with fire and steel."

"Saint Michael! you dare tell me that!" cried Karl, and his grey eyes flamed with anger at the Northman's audacity.

"My tale is not all told," said Olvir, unmoved.

"I have heard enough! You have slain Count Roland's henchmen, stolen my wares, and now you come to mock--"

"No, sire! no!" cried Roland, and he sprang before the Northman, who was turning haughtily away, his dark face no less angry than the king's. "Hold, brother! One word, sire! It was not he who slew my followers; he saved us from the clutches of Wittikind's man, a terrible Dane count, whom he slew in single combat. While I lay witless from my wounds, he granted the prayer of the little princess that we be brought to you; he won over the warriors of the Dane count to join his banner; yet more, he plighted brotherhood with me, after the old custom."

"As to your wares, Frank king," broke in Olvir, hotly, "bale and cask lie in my longships, untouched. Now I cast them ashore, and weigh anchor."

"No, by my sword; that you shall not!" cried Karl, and in a stride he was beside the young Northman. "Hold, kin of Otkar. I have done wrong; I will repay."

"Hold, brother, for my sake!" urged Roland, his arm about Olvir's shoulder.

The sea-king half turned, his nostrils quivering with passion, and stared fiercely about from the astonished Frank lords to their king. But before the look on Karl's grand face his anger broke and subsided as quickly as it had flared out.

"Have your will, lord king," he muttered. "I will listen, though that is not our custom in the North after words such as have been spoken here."

"Then I eat those words, my bold Dane. Wait; that is not enough! My hot anger has done you wrong. I will pay in full. Yet first, tell me why you sought vengeance against me,--you and Otkar. Why did your foster-father stir up strife between me and my brother Carolman? Why did he spur Desiderius, the weak Lombard, to war?"

Olvir's breast heaved, and his nostrils quivered; but he answered steadily: "It was thus, lord king: in your youth you laid an ambush near the Rhine mouth for a band of vikings."

"It was my first battle. The Danes had a famous hero for leader."

"He was my father."

"So--now I understand," muttered Karl, and his brows met in deep thought. "You have been generous, young count. Name what blood-fine you would have. I will pay it over without dispute."

"I do not come for wergild, lord king. While I thought you my father's slayer, nothing but blood could have paid for the wrong. And the debt is paid in blood; for before I slew that vile Dane, I learned from his own lips that he, who had betrayed my father, also was his bane,--that you sought to save the stricken hero."

"He thrust me aside; I was yet a child. I wish now that I had hung the blood-eager boar."

"Not so, king; else I might never have learned that I had no cause to hate you. I owe thanks to the braggart. But for his boasts, I doubt if I should have yielded to the little maid's entreaty."

"It was a Christian deed!" exclaimed Karl.

Olvir smiled: "Say rather, a Christly deed. I have read the runes of the White Christ; but, also, I have heard what Otkar had to say of your Christian priests and their flocks. By Thor! beneath the fleece, if Otkar spoke truth, they differ little from those whom you call heathen wolves."

"True--true! though the charge is bitter from the lips of a pagan. Yet Holy Church is the only fold, however much defiled by evil men. Already I have set about the cleansing of the sacred cloisters. Before I have ended that task, I hope that you and all your followers will have come within the pale."

"But now, lord king, all my men are sons of Thor and Odin; and I, like Otkar, trust neither in the old gods nor the new,--only in my own might. Can you welcome us so? I have heard how you force baptism upon the Saxons."

"As a nation of savage pagans, they menace my kingdom. I must bend them to Holy Church, or in time to come they will sweep across the Rhine and lay desolate the work I seek to upbuild. It is otherwise with your following, my Dane hawk. You are free to choose or reject Christ, as you are free to come and go. It is my trust that you will see the Truth and stay with me always."

"For this war, at least, we shall fight beneath your standard. Your foe will not easily break the shieldburg of my sea-wolves."

"That I can well believe if they are worthy of their leader."

"You shall view them now, lord king!" exclaimed Olvir, and, wheeling about, he sent a clear command ringing down the bank.

Hardly was the word uttered when from all five longships the armed crews poured overboard and swarmed up the shore like a storming party. So fierce, indeed, was their rush that many of the Frankish warriors mistook it for a real attack. When three or four counts, with Hardrat at their head, raised the cry of treachery, a thousand loyal men ran, shouting, to throw themselves between their king and the heathen.

But Karl sprang before his warriors, with angry commands to halt, and the movement was checked as suddenly as it had started. Yet, prompt as was the king's action, there was one sword which swung before he could utter his first command.

The moment Hardrat saw the Franks come running, he ceased his shouts and wheeled upon Olvir, with upraised sword, thinking to cut him down unawares. He might easier have surprised a hungry leopard. Before the blow could fall, the Northman had thrust Roland out of danger and leaped in under the descending blade. His arms closed about the burly Thuringian like steel bands. There was no time given Hardrat to break loose or to strike. He was flung up bodily and cast headlong over Olvir's shoulder.

The Thuringian's astonishment was exceeded only by his rage. Half stunned, he sat up, staring wide-eyed, and groped for his sword-hilt. But Olvir caught up the weapon, and, snapping the broad blade on his knee, tossed the fragments back to their owner with careless scorn.

"Ho! the red pig has a tumble!" roared Liutrad, at the head of the vikings, and the grim warriors burst into jeering laughter.

"Saint Michael! who jests at so ill a time?" demanded Karl; and he wheeled about, his face flushed, and his great figure quivering with anger.

Olvir answered him, smiling, "My sea-wolves, lord king. This fair-haired hero and I have played a merry game behind your back."

"A game for which Hardrat should hang, sire!" exclaimed Roland. "He sought to cut down Count Olvir unawares."

The angry flush on the king's face deepened, and he confronted Hardrat with a look before which the stout warrior visibly trembled.

"Well for you, Thuringian, your sword did no harm!" he cried. "Lightly as the young hero takes it, I am yet minded to ride you on the nearest tree."

"Forgive the deed, sire! I was over-hasty,--I thought the heathen were about to attack your Majesty," stammered Hardrat.

"We will allow the plea; the thought was loyal, however ill-advised. Your broken sword shall be the punishment for your rashness."

Had Karl been less keenly intent on the movements of the vikings, the affair might not have passed so lightly for the Thuringian. But as Olvir made no demand for redress, the king turned away, to watch with a kindling eye the manoeuvres of the Northmen.