*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 42163 ***

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY . .

T. LEMAN HARE

BERNARDINO LUINI

In the Same Series

| Artist. | Author. |

| VELAZQUEZ. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. | Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. | Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. | Lucien Pissarro. |

| BELLINI. | George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. | James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. | Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. | Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. | Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. | George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. | Max Rothschild. |

| TINTORETTO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| LUINI. | James Mason. |

| FRANZ HALS. | Edgcumbe Staley. |

| |

| In Preparation |

| VAN DYCK. | Percy M. Turner. |

| WHISTLER. | T. Martin Wood. |

| LEONARDO DA VINCI. | M. W. Brockwell. |

| RUBENS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| BURNE-JONES. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| J. F. MILLET. | Percy M. Turner. |

| CHARDIN. | Paul G. Konody. |

| FRAGONARD. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| HOLBEIN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| BOUCHER. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| VIGÉE LE BRUN. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| WATTEAU. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| MURILLO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| And Others. |

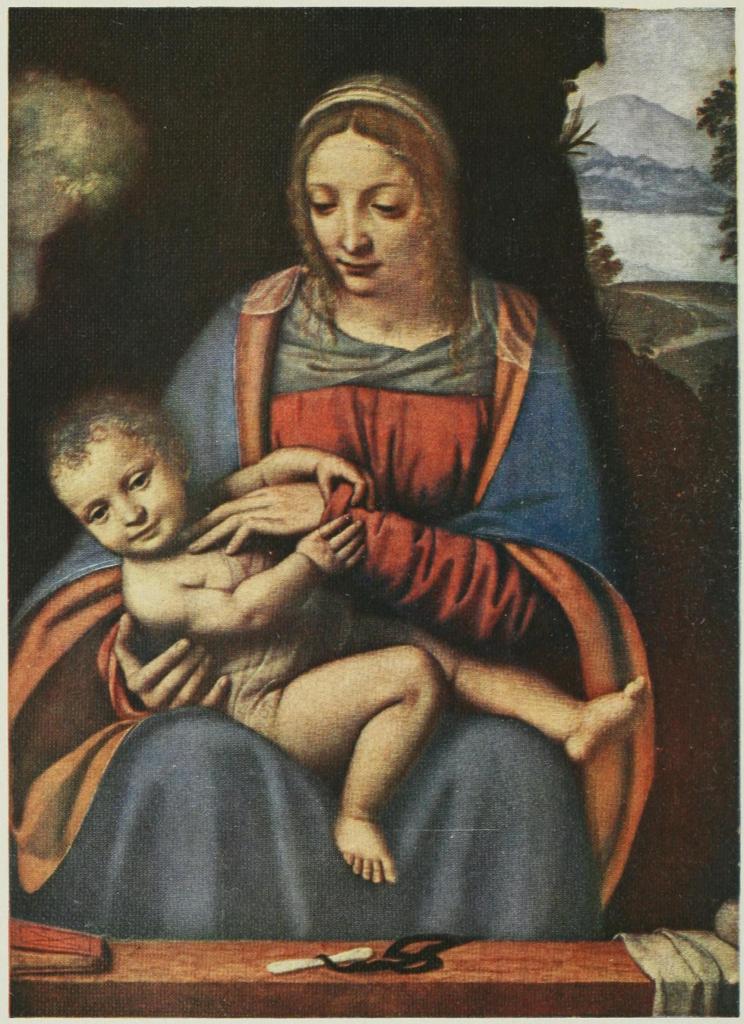

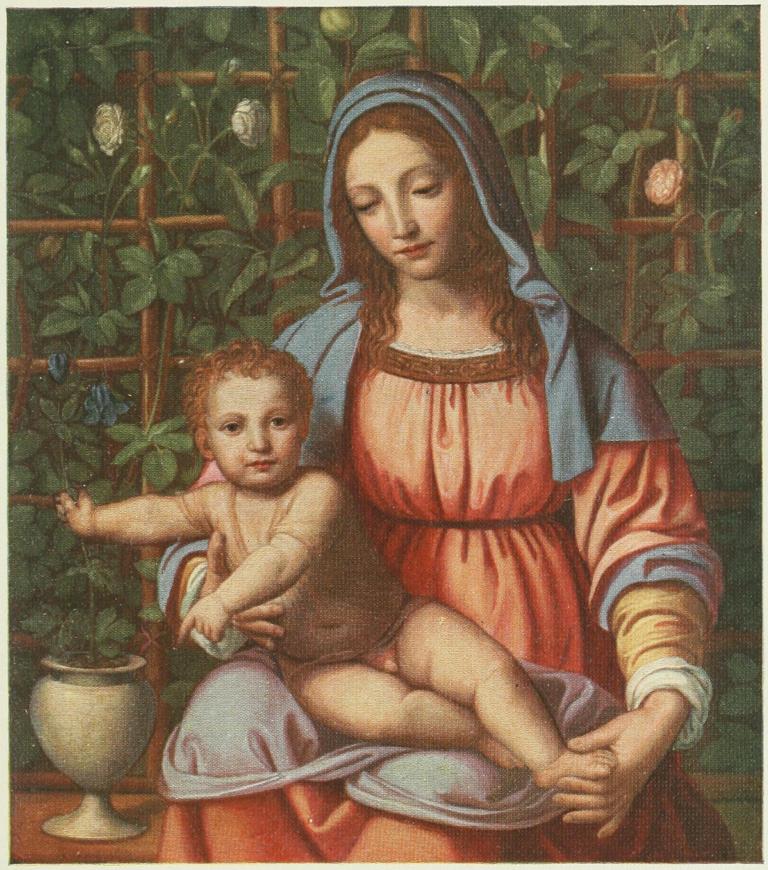

PLATE I.—MADONNA AND CHILD. Frontispiece

(In the Wallace Collection)

This is another admirably painted study of the artist’s favourite

subject. The attitude of the child is most engaging, the painting of

the limbs is full of skill, and the background adds considerably to the

picture’s attractions. It will be noted that Luini appears to have

employed the same model for most of his studies of the Madonna.

Bernardino

LUINI

BY JAMES MASON

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES CO.

[Pg vii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Plate |

| I. | Madonna and Child | Frontispiece |

| In the Wallace Collection |

| | Page |

| II. | Il Salvatore | 14 |

| In the Ambrosiana, Milan |

| III. | Salomé and the Head of St. John the Baptist | 24 |

| In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence |

| IV. | The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine | 34 |

| In the Brera, Milan |

| V. | The Madonna of the Rose | 40 |

| In the Brera, Milan |

| VI. | Detail of Fresco | 50 |

| In the Brera, Milan |

| VII. | Head of Virgin | 60 |

| In the Ambrosiana, Milan |

| VIII. | Burial of St. Catherine | 70 |

| In the Brera, Milan |

[Pg 9]

I

A RETROSPECT

In the beginning of the long and fascinating

history of Italian Art we see that

the spirit of the Renaissance first fluttered

over the minds of men much as the spirit

of life is said have moved over the face[Pg 10]

of the waters before the first chapter of

creation’s marvellous story was written.

Beginnings were small, progress was slow,

and the lives of the great artists moved

very unevenly to their appointed end.

There were some who rose to fame and

fortune during their life, and then died so

completely that no biography can hope to

rouse any interest in their work among

succeeding generations.

There were others who worked in silence

and without réclame of any sort, content

with the respect and esteem of those with

whom they came into immediate contact,

indifferent to the plaudits of the crowd or

the noisy praises of those who are not

qualified to judge. True servants of the

western world’s religion, they translated

work into terms of moral life, and moral[Pg 11]

life into terms of work. Merit like truth

will out, and when time has sifted good

work from bad and spurious reputations

from genuine ones, many men who fluttered

the dovecotes of their own generation disappear

from sight altogether; some others

who wrought unseen, never striving to gain

the popular ear or eye, rise on a sudden to

heights that might have made them giddy

had they lived to be conscious of their own

elevation. They were lowly, but their fame

inherits the earth.

Bernardino Luini, the subject of this

little study, calls us away from the great

art centres—from Venice and Florence and

Rome; his record was made and is to be

found to-day amid the plains of Lombardy.

Milan is not always regarded as one of the

great art centres of Italy in spite of the[Pg 12]

Brera, the Ambrosiana, and the Poldi Pezzoli

Palace collections, but no lover of pictures

ever went for the first time to the galleries

of Milan in a reverent spirit and with a

patient eye without feeling that he had

discovered a painter of genius. He may

not even have heard his name before, but

he will come away quite determined to learn

all he may about the man who painted the

wonderful frescoes that seem destined to

retain their spiritual beauty till the last faint

trace of the design passes beyond the reach

of the eye, the man who painted the panel

picture of the “Virgin of the Rose Trees,”

reproduced with other of his master-works

in these pages.

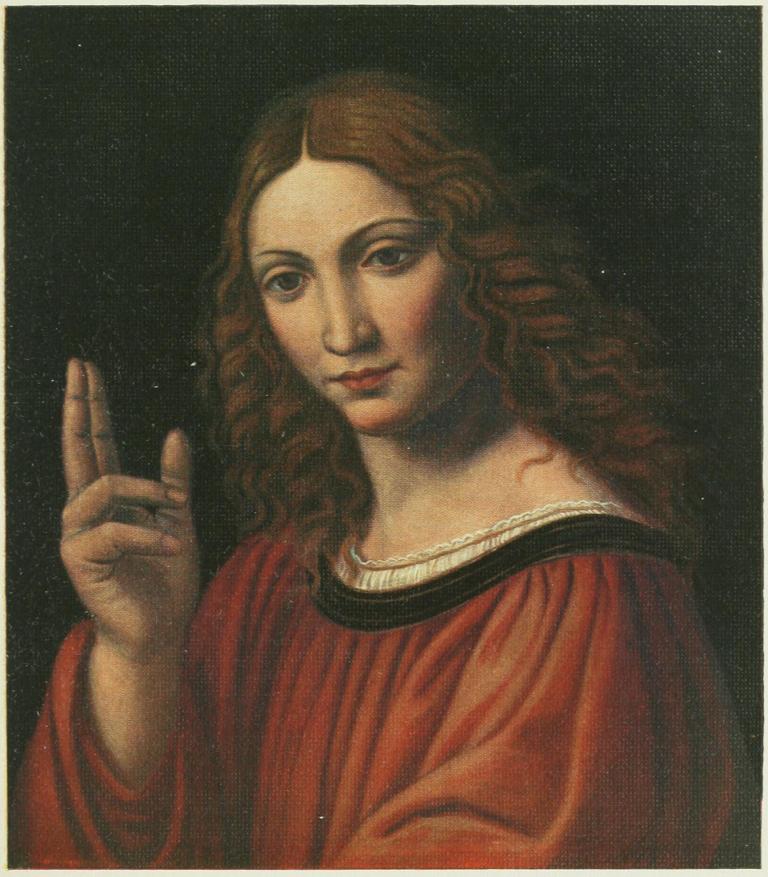

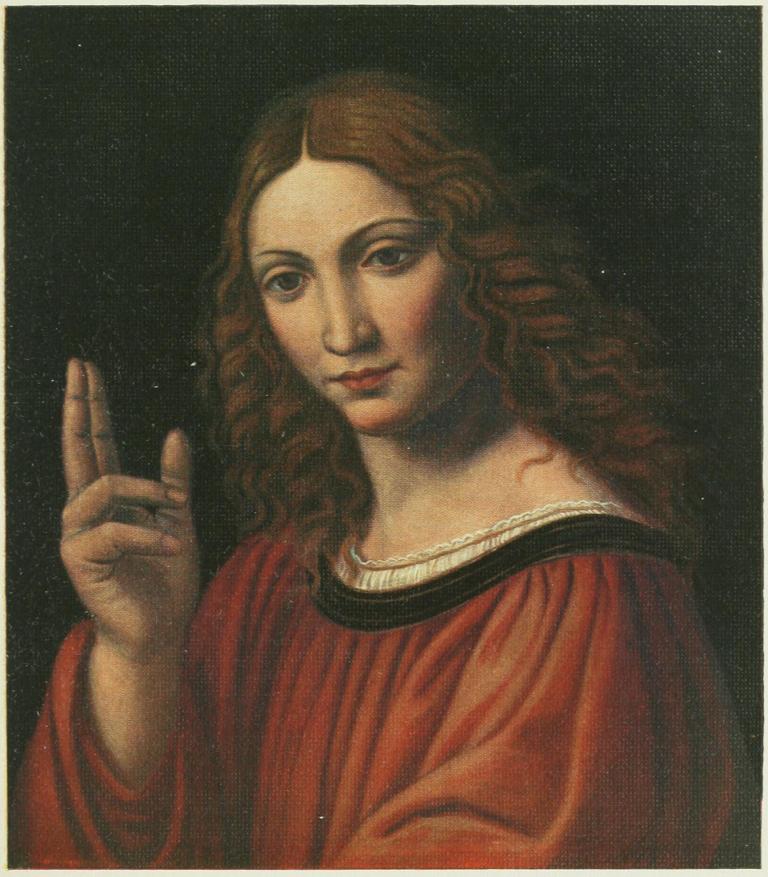

PLATE II.—IL SALVATORE

(In the Ambrosiana, Milan)

This picture, one of the treasures of the beautiful collection in the

Pinacoteca of Ambrosiana in the Piazza della Rosa, hangs by the

same artist’s picture of “John the Baptist as a Child.” The right hand

of Christ is raised in the attitude of benediction, and the head has

a curiously genuine beauty. The preservation of this picture is

wonderful, the colouring retains much of its early glow. The head

is almost feminine in its tenderness and bears a likeness to Luini’s

favourite model.

To go to the Brera is to feel something

akin to hunger for the history of Bernardino

Luini or Luino or Luvino as he is called

[Pg 15]

by the few who have found occasion to

mention him, although perhaps Luini is the

generally accepted and best known spelling

of the name. Unfortunately the hungry

feeling cannot be fully satisfied. Catalogues

or guide books date the year of Luini’s

birth at or about 1470, and tell us that he

died in 1533, and as this is a period that

Giorgio Vasari covers, we turn eagerly to

the well-remembered volumes of the old

gossip hoping to find some stories of the

Lombard painter’s life and work. We are

eager to know what manner of man Luini

was, what forces influenced him, how he

appeared to his contemporaries, whether

he had a fair measure of the large success

that attended the leading artists of his day.

Were his patrons great men who rewarded

him as he deserved—how did he fare when[Pg 16]

the evening came wherein no man may

work? Surely there is ample scope for the

score of quaint comments and amusing if

unreliable anecdotes with which Vasari

livens his pages. We are confident that

there will be much to reward the search, because

Bernardino Luini and Giorgio Vasari

were contemporaries after a fashion. Vasari

would have been twenty-one years old

when Luini died, the writer of the “Lives”

would have seen frescoes and panel pictures

in all the glory of their first creation. He

could not have failed to be impressed by

the extraordinary beauty of the artist’s conceptions,

the skill of his treatment of single

figures, the wealth of the curious and elusive

charm that we call atmosphere—a charm to

which all the world’s masterpieces are indebted

in varying degrees—the all-pervading[Pg 17]

sense of a delightful and refined personality,

leaves us eager for the facts that must have

been well within the grasp of the painter’s

contemporaries.

Alas for these expectations! Vasari

dismisses Bernardino del Lupino, as he

calls him, in six or eight sentences, and

what he says has no biographical value at

all. The reference reads suspiciously like

what is known in the world of journalism

as padding. Indeed, as Vasari was a fair

judge, and Bernardino Luini was not one

of those Venetians whom Vasari held more

or less in contempt, there seems to be

some reason for the silence. Perhaps it

was an intimate and personal one, some

unrecorded bitterness between the painter

and one of Vasari’s friends, or between

Vasari himself and Luini or one of his[Pg 18]

brothers or children. Whatever the cause

there is no mistake about the result. We

grumble at Vasari, we ridicule his inaccuracies,

we regret his limitations, we scoff

at his prejudices, but when he withholds

the light of his investigation from contemporary

painters who did not enjoy the

favour of popes and emperors, we wander

in a desert land without a guide, and search

with little or no success for the details that

would serve to set the painter before us.

Many men have taken up the work of investigation,

for Luini grows steadily in favour

and esteem, but what Vasari might have done

in a week nobody has achieved in a decade.

A few unimportant church documents

relating to commissions given to the painter

are still extant. He wrote a few words

on his frescoes; here and there a stray[Pg 19]

reference appears in the works of Italian

writers of the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, but our knowledge when it has

been sifted and arranged is remarkably

small and deplorably incomplete. Dr. J. C.

Williamson, a painstaking critic and a competent

scholar, has written an interesting

volume dealing with the painter, and in the

making of it he has consulted nearly fifty

authorities—Italian, French, English, and

German—only to find it is impossible to

gather a short chapter of reliable and consecutive

biography from them all. Our

only hope lies in the discovery of some

rich store of information in the public or

private libraries of Milan among the manuscripts

that are the delight of the scholars.

Countless documents lie unread, many

famous libraries are uncatalogued, the[Pg 20]

archives of several noble Italian houses

that played an important part in fifteenth

and sixteenth century Italy have still to

be given to the world. It is not unreasonable

to suppose that records of Luini’s life

exist, and in these days when scholarship

is ever extending its boundaries there is

hope that some scholar will lay the ever

growing circle of the painter’s admirers

under lasting obligations. Until that time

comes we must be content to know the

man through the work that he has left

behind him, through the medium of fading

frescoes, stray altarpieces, and a few panel

pictures. Happily they have a definite and

pleasant story to tell.

We must go to Milan for Luini just as

we must go to Rome for Raphael and to

Madrid for Velazquez and Titian and to[Pg 21]

Venice for Jacopo Robusti whom men still

call the Little Dyer (Tintoretto). In London

we have one painting on wood, “Christ and

the Pharisees,” brought from the Borghese

Palace in Rome. The head of Christ is

strangely feminine, the four Pharisees round

him are finely painted, and the picture has

probably been attributed to Leonardo da

Vinci at some period of its career. There

are three frescoes in South Kensington and

a few panel pictures in private collections.

The Louvre is more fortunate than our

National Gallery, it has several frescoes

and two or three panels. In Switzerland,

in the Church of St. Mary and the Angels

in Lugano, is a wonderful screen picture

of the “Passion of Christ” with some hundreds

of figures in it, and the rest of

Luini’s work seems to be in Italy. The[Pg 22]

greater part is to be found in Milan, some

important frescoes having been brought to

the Brera from the house of the Pelucca

family in Monza, while there are some important

works in Florence in the Pitti and

Uffizi Galleries. In the Church of St. Peter

at Luino on the shores of Lake Maggiore,

the little town where Benardino was born

and from which he took his name, there

are some frescoes but they are in a very

faded condition. The people of the lake

side town have much to say about the master

who has made Luino a place of pilgrimage

but their stories are quite unreliable.

PLATE III.—SALOMÉ AND THE HEAD OF ST. JOHN

THE BAPTIST

(In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

In this striking and finely preserved picture Bernardino Luini has

contrived to avoid all sense of horror. The head of the dead John

the Baptist is full of beauty, and even Herodias is handled without

any attempt to make her repulsive. Sufficient contrast is supplied

by the executioner on the right.

It might be held, seeing that the artist’s

work is scanty, and often in the last stages

of decay, while his life story has faded quite

from the recovered records of his contemporaries,

that Luini is hardly fit subject for

[Pg 25]

discussion here. In a series of little books

that seeks to introduce great artists to new

friends through the medium of reproductions

that show the work as it is, and a brief

concise description that aims at helping

those who are interested to study the

master for themselves, there is a temptation

to deal only with popular men. These

give no trouble to their biographer or his

readers, but after all it is not the number

of pictures that an artist paints or the

wealth of detail that his admirers have

collected that establishes his claim to be

placed among the immortals. His claim

rests upon the quality of the work done,

its relation to the times in which it was

painted, the mood or spirit it reveals, the

light it throws upon the mind that conceived

and the hand that executed it.[Pg 26]

We know enough and to spare of the

more flamboyant personalities of the

Venetian and Florentine schools. Long

periods of study will not exhaust all there

is to learn about men like Titian, Michelangelo,

Raphael of Urbino, and the rest,

but Luini, though he left no written record,

will not be denied. We dare not pass him

by, seeing that we may introduce him to

some admirers who will, in days to come,

seek and find what remains beyond our

reach at present. His appeal is so irresistible,

the beauty of his work is so rare and

so enduring that we must endeavour to the

best of our ability, however small it be, to

declare his praise, to stimulate inquiry,

enlarge his circle, and give him the place

that belongs to him of right. There are

painters in plenty whose work is admired[Pg 27]

and praised, whose claims we acknowledge

instantly while admitting to ourselves that

we should not care to live with their pictures

hanging on round us. The qualities of

cleverness and brilliance pall after a little

time, the mere conquest of technical difficulties

of the kind that have been self-inflicted

rouses admiration for a while and

then leaves us cold. But the man who is

the happy possessor of a fresco or a panel

picture by Luini is to be envied. Even he

who lives in the neighbourhood of some

gallery or church and only sees the rare

master’s works where, “blackening in the

daily candle smoke, they moulder on the

damp wall’s travertine,” will never tire of

Luini’s company. He will always find inspiration,

encouragement, or consolation in

the reflection of the serene and beautiful[Pg 28]

outlook upon life that gave the work so

much of its enduring merit. Luini, whatever

manner of man he may have been,

was so clearly enamoured of beauty, so

clearly intolerant of what is ugly and unrefined,

that he shrank from all that was

coarse and revolting either in the life around

him or in certain aspects of the Bible stories

that gave him subjects for his brush. Beauty

and simplicity were the objects of his unceasing

search, his most exquisite expression.

Like all other great painters he had his

marked periods of development, his best

work was done in the last years of his life,

but there is nothing mean or trivial in any

picture that he painted and this is the

more to his credit because we know from

the documents existing to-day that he lived

in the world and not in the cloister. We[Pg 29]

admire the perennial serenity of Beato

Angelico, we rejoice with him in his exquisite

religious visions. The peaceful

quality of his painting and the happy

certainty of his faith move us to the deepest

admiration, but we may not forget that

Angelico lived from the time when he was

little more than a boy to the years when

he was an old man in the untroubled atmosphere

of the monastery of San Marco in

Florence, that whether he was at home in

that most favoured city or working in the

Vatican at Rome, he had no worldly troubles.

Honour, peace, and a mind at peace with

the world were with him always.

Bernardino Luini on the other hand

travelled from one town in Italy to another,

employed by religious houses from time to

time, but always as an artist who could be[Pg 30]

relied upon to do good work cheaply. He

could not have been rich, he could hardly

have been famous, it is even reasonable

to suppose that his circumstances were

straitened, and on this account the unbroken

serenity of his work and his faithful

devotion to beauty are the more worthy of

our praise. What was beautiful in his life

and work came from within, not from without,

and perhaps because he was a stranger

to the cloistered seclusion that made Fra

Angelico’s life so pleasantly uneventful his

work shows certain elements of strength that

are lacking from the frescoes that adorn the

walls of San Marco to this day. To his

contemporaries he was no more than a little

planet wandering at will round those fixed

stars of the first magnitude that lighted all

the world of art. Now some of those great[Pg 31]

stars have lost their light and the little

planet shines as clear as Hesperus.

II

As we have said already nothing is

known of Luini’s early life, although the

fact that he was born at Luino on the Lago

Maggiore seems to be beyond dispute. The

people of that little lake side town have

no doubt at all about the matter, and they

say that the family was one of some distinction,

that Giacomo of Luino who founded

a monastery in his native place was the

painter’s uncle. Perhaps the wish was

father to the thought, and because every

man who sets out to study the life and

work of an artist is as anxious to know as

was Miss Rosa Dartle herself, there are

always facts of a sort at his service. He[Pg 32]

who seeks the truth can always be supplied

with something as much like it as paste

is to diamonds, and can supplement the

written word with the aid of tradition.

The early life of the artist is a blank, and

the authorities are by no means in agreement

about the year of his birth. 1470

would seem to be a reasonable date, with

a little latitude on either side. Many men

writing long years after the painter’s death,

have held that he was a pupil of Leonardo

da Vinci, indeed several pictures that were

attributed to da Vinci by the authorities

of different European galleries are now recognised

as Luini’s work, but the mistake

is not at all difficult to explain. If we turn

to “La Joconda,” a portrait by da Vinci

that hangs in the Louvre to-day, and is

apparently beyond dispute in the eyes of

[Pg 35]

the present generation of critics, and then

go through the Brera in Milan with a

photograph of “La Joconda’s” portrait in

our hand, it will be impossible to overlook

the striking resemblance between Luini’s

types and da Vinci’s smiling model. Leonardo

had an academy in Milan, and it is

reasonable to suppose that Luini worked in

it, although at the time when he is supposed

to have come for the first time to the capital

of Lombardy, Leonardo da Vinci had left,

apparently because Louis XII. of France,

cousin and successor of that Charles VIII.

who had troubled the peace of Italy for so

long, was thundering at the city gates, and

at such a time great artists were apt to

remember that they had good patrons elsewhere.

The school may, however, have remained

open because no great rulers made[Pg 36]

war on artists, and Luini would have learned

something of the spirit that animated Leonardo’s

pictures. For other masters and

influence he seems to have gone to Bramantino

and Foppa. Bramantino was a

painter of Milan and Ambrosio Foppa

known as Caradosso was a native of Pavia

and should not be reckoned among Milanese

artists as he has so often been. He was

renowned for the beauty of his medals and his

goldsmith’s work; and he was one of the men

employed by the great family of Bentivoglio.

PLATE IV.—THE MYSTIC MARRIAGE OF ST. CATHERINE

(In the Brera, Milan)

This is a singularly attractive picture in which the child Christ

may be seen placing the ring upon the finger of St. Catherine. The

little open background, although free from the slightest suggestion

of Palestine, is very charming, and the head of the Virgin and St.

Catherine help to prove that Luini used few models.

It may be mentioned in this place that

many Italian artists, particularly those of

the Florentine schools, suffered very greatly

from their unceasing devotion to the art of

the miniaturist. They sought to achieve

his detail, his fine but cramped handling,

and this endeavour was fatal to them[Pg 37]

when they came to paint large pictures

that demanded skilled composition, and the

subordination of detail to a large general

effect. The influence of the miniature

painter and the maker of medals kept

many a fifteenth-century painter in the

second grade and Luini never quite survived

his early devotion to their methods,

often making the fatal mistake of covering

a large canvas with many figures of varying

size but equal value. It may be remarked

that Tintoretto was the first great

painter of the Renaissance who learned to

subordinate parts to the whole, and he

had to face a great deal of unpopularity

because he saw with his own eyes instead

of using those of his predecessors.

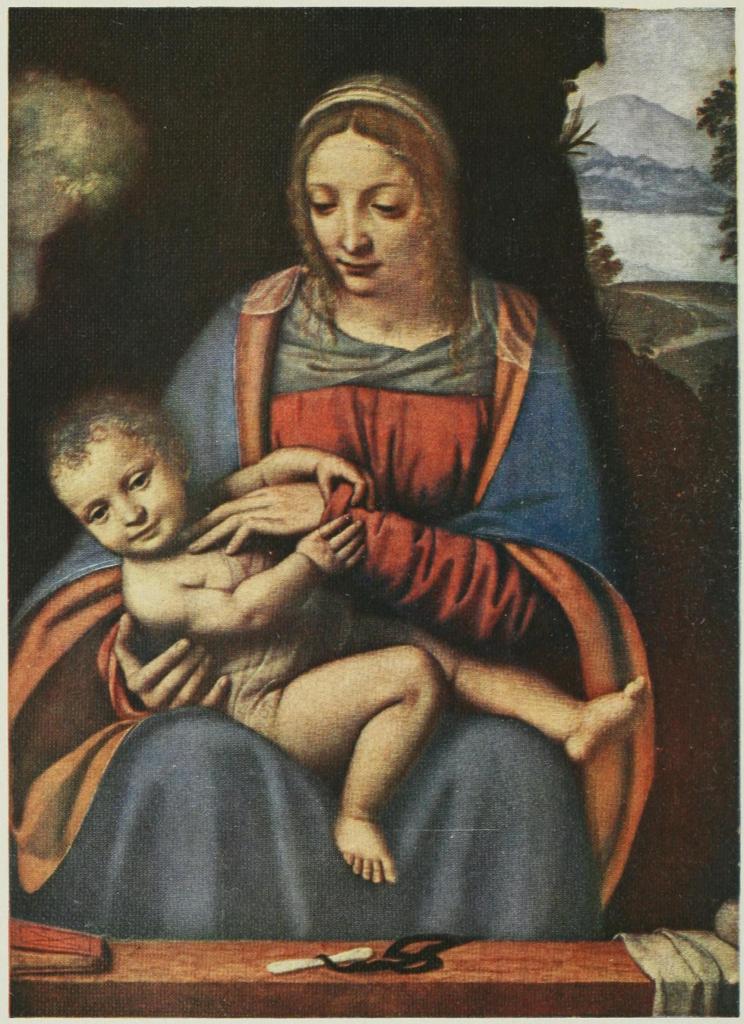

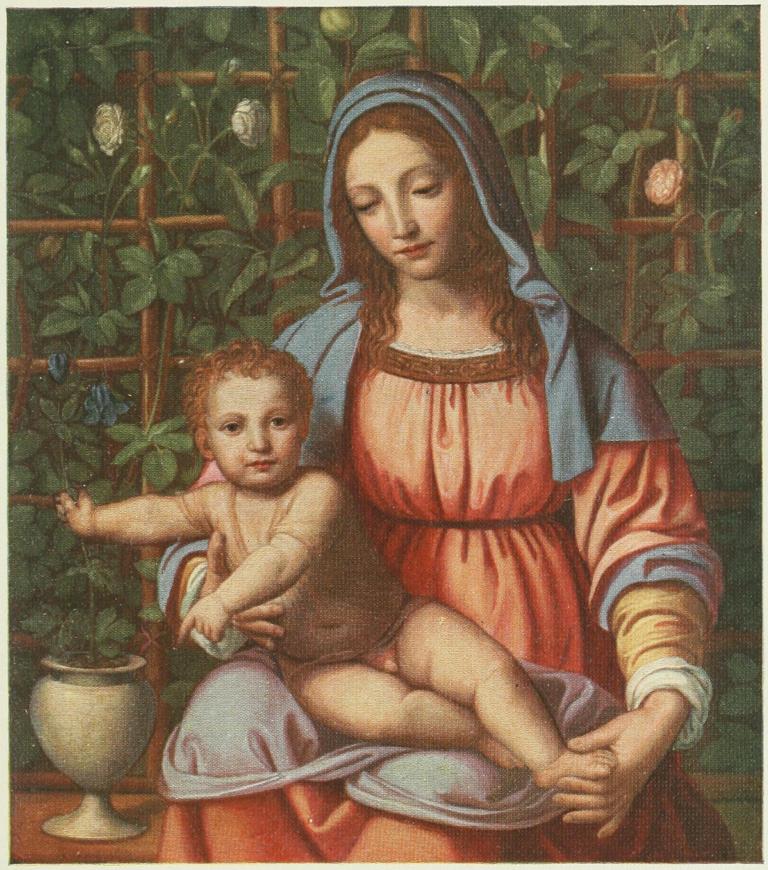

PLATE V.—THE MADONNA OF THE ROSE

(In the Brera, Milan)

Modern criticism proclaims this picture of the Virgin in a Bower of

Roses to be the finest of the master’s paintings. Not only is it

delightfully composed and thought out but the background is painted

with rare skill, and the colour is rich and pleasing to this day.

It may be suggested, with all possible

respect to those who hold different opinions,[Pg 38]

that Luini, though he responded to certain

influences, had no master in the generally

accepted sense of the term. One cannot

trace the definite relation between him and

any older painter that we find between

Titian and Gian Bellini, for example. He

took a certain type from Leonardo, his

handling from time to time recalls the

other masters—we have already referred to

the most important of these—but had he

studied in the school of one man, had he

served an apprenticeship after the fashion

of his contemporaries, his pictures would

surely have been free from those faults of

composition and perspective that detract

so much from the value of the big works.

He seems to have been self-taught rather

than to have been a schoolman. While his

single figures are wholly admirable whether

[Pg 41]

on fresco or on panel, his grouping is nearly

always ineffective, one might say childish,

and his sense of perspective is by no means

equal to that of his greatest contemporaries.

As a draughtsman and a colourist Luini had

little to learn from anybody, and the poetry

of his conceptions is best understood when

it is remembered that he was a poet as well

as a painter. He is said to have written

poems and essays, though we are not in a

position to say where they are to be found,

and it is clear that he had a singularly detached

spirit and that the hand of a skilled

painter was associated with the mind of a

little child. In some aspects he is as simple

as those primitive painters of Umbria whose

backgrounds are all of gold. Like so many

other painters of the Renaissance Luini’s

saints and angels are peasant folk, the people[Pg 42]

he saw around him. He may have idealised

them, but they remain as they were made.

A few records of the prices paid for

Luini’s work exist among the documents

belonging to churches and religious houses,

and while they justify a belief that at the

time he came to Milan Luini had achieved

some measure of distinction in his calling,

they seem to prove that he was hardly regarded

as a great painter. The prices paid

to him are ridiculously small, no more than

a living wage, but he had the reputation of

being a reliable and painstaking artist and

he would seem to have been content with

a small reward for work that appealed to

him. His early commissions executed in

and around Milan when he first came from

Luini were numerous and consisted very

largely of frescoes which are the work of a[Pg 43]

young man who has not yet freed his own

individuality from the influence of his elders.

One of the most charming works associated

with this period is the “Burial of St.

Catherine,” which is reproduced in these

pages. The composition is simple enough,

the handling does not touch the summit of

the painter’s later achievements, but the

sentiment of the picture is quite delightful.

St. Catherine is conceived in a spirit of

deepest reverence and devotion, but the

angels are just Lombardy peasant girls

born to labour in the fields and now decorated

with wings in honour of a great

occasion. And yet the man who could

paint this fresco and could show so unmistakably

his own simple faith in the story

it sets out, was a poet as well as a painter

even though he had never written a line,[Pg 44]

while the treatment of his other contemporary

frescoes and the fine feeling for appropriate

colour suggest a great future for the

artist who had not yet reached middle age.

We see that Luini devoted his brush to

mythological and sacred subjects, touching

sacred history with a reverent hand, shutting

his eyes to all that was painful, expressing

all that was pitiful or calculated

to strengthen the hold of religion upon the

mass in fashion destined to appeal though

in changing fashion for at least four centuries.

Where the works have failed to

triumph as expressions of a living faith

they have charmed agnostics as an expression

of enduring beauty.

From Milan Luini seems to have gone

to Monza, a city a few miles away from

the capital of Lombardy where the rulers[Pg 45]

of united Italy come after their coronation

to receive the iron crown that has been

worn by the kings of Lombardy for nearly

a thousand years. This is the city in

which the late King Umberto, that brave

and good man, was foully murdered by an

anarchist. To-day one reaches Monza by

the help of a steam-tram that blunders

heavily enough over the wide flat Lombardy

plain. The Milanese go to Monza for the

sake of an outing, but most of the tourists

who throng the city stay away, and it is

possible to spend a few pleasant hours in

the cathedral and churches with never a

flutter of red-covered guide book to distract

one’s attention from the matters to

which the hasty tourist is blind. Here

Luini painted frescoes, and it is known that

he stayed for a long time at the house of[Pg 46]

one of the strong men of Monza and

painted a large number of frescoes there.

To-day the fortress, if it was one, has

become a farmhouse, and the frescoes,

more than a dozen in all, have been taken

away to the Royal Palace in Milan. Dr.

Williamson in his interesting volume to

which the student of Luini must be deeply

indebted, says that there is one left at the

Casa Pelucca. The writer in the course

of two days spent in Monza was unfortunate

enough to overlook it.

It has been stated that the facts relating

to Luini’s life are few and far between.

Fiction on the other hand is plentiful, and

there is a story that Luini, shortly after

his arrival in Milan, was held responsible

by the populace for the death of a priest

who fell from a hastily erected scaffolding[Pg 47]

in the church of San Giorgio where the

artist was working. The rest of the legend

follows familiar lines that would serve the

life story of any leading artist of the time,

seeing that they all painted altar-pieces

and used scaffolding. He is said to have

fled to Monza, to have been received by

the chief of the Pelucca family, to have

paid for his protection with the frescoes

that have now been brought from Monza

to the Brera, to have fallen violently in

love with the beautiful daughter of the

house, to have engaged in heroic contests

against great odds on her behalf, and so on,

ad absurdum. If we look at the portraits

the painter is said to have made of himself

and to have placed in pictures at

Saronna and elsewhere we shall see that

Luini was hardly the type of man to have[Pg 48]

engaged in the idle pursuits of chivalry in

the intervals of the work to which his life

was given. We have the head of a man

of thought not that of a man of action,

and all the character of the face gives the

lie to the suggestions of the storytellers.

It is clear, however, that the painter made

a long stay in Monza and when he came

back to Milan he worked for the churches

of St. Maurizio, Santa Maria della Pace,

Santa Maria di Brera, and St. Ambrosia.

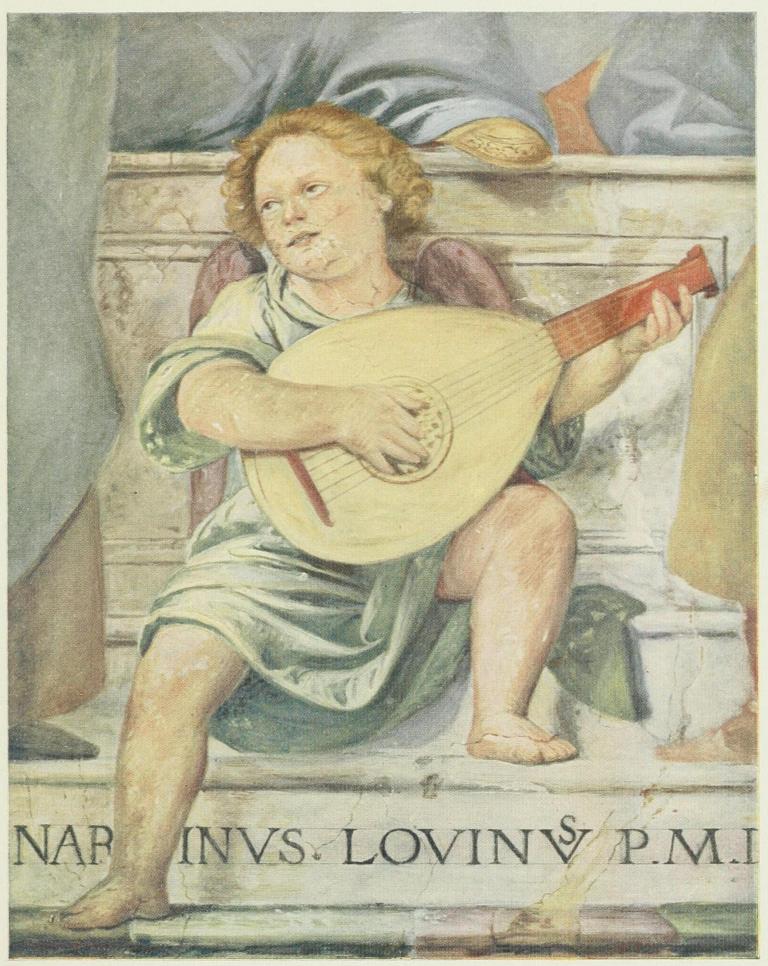

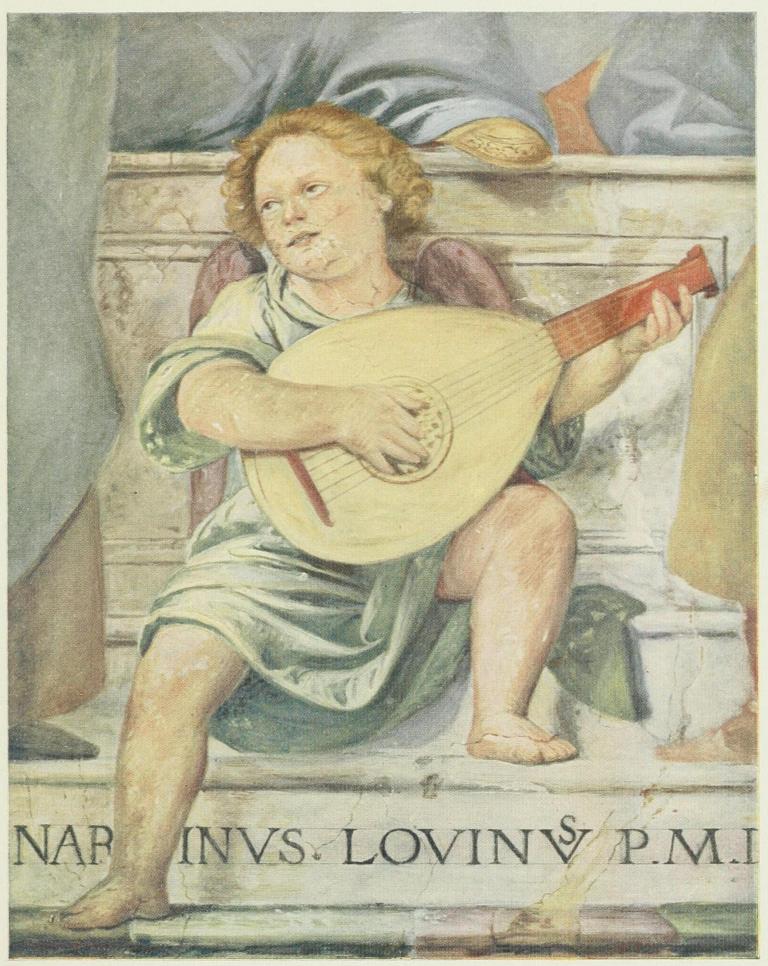

PLATE VI.—DETAIL OF FRESCO

(In the Brera, Milan)

This prettily posed figure is at the base of a fresco of the Virgin

with Saints in the Brera. Part of the artist’s signature (Bernardinus

Louinus) may be seen below. It will be remembered that Carpaccio

painted a very similar subject. The fresco is not too well preserved.

In Milan he found a great patron, no

less a man than Giovanni Bentivoglio who

had been driven from his rule over Bologna

by the “Terrible Pontiff” Julius II., that

life-long opponent and bitter enemy of the

Borgia Pope Alexander VI. Alessandro

Bentivoglio, the son of the ruined Giovanni,

married Ippolita Sforza, daughter of one

[Pg 51]

of the house that had done so much to

rule Rome until Pope Alexander VI. broke

its power. Alessandro Bentivoglio commissioned

Luini to paint altar-pieces in

St. Maurizio where his father was buried, and

the painter included in his work a portrait of

Ippolita Sforza with three female saints. He

did much other work in this church; some of

it has faded almost beyond recognition.

At the same time there is no need to

think that we have recovered the last work

of Luini or indeed of the great masters

even in the churches of Italy. Only a few

months ago the writer was in a small

Italian church that had suffered a few

years ago from disastrous floods. The

water unable to find no outlet had risen

for a time almost to the top of the supporting

columns. The smooth wall above was[Pg 52]

plastered, and when the waters had subsided

it was found that the plaster had become

so damaged that it was necessary to remove

it. Happily the work was done

carefully, for under the whitewash some

excellent frescoes were discovered. They

would seem to have profited by their covering

for as much as has been uncovered is

rich and well preserved. It may be that

in days when the State of Italy was seriously

disturbed, and Napoleon, greatest of highwaymen

and conquerors, after being crowned

in Milan with the famous Monza crown,

was laying his hand on all that seemed

worth carrying away, some one in authority

thought of this simple method of concealment,

and obtained expert advice that

enabled the frescoes to be covered without

serious damage. Under similar conditions[Pg 53]

we may yet discover some of the earlier

work of Luini, because it is clear that the

years in which his reputation was in the

making must have been full of achievement

of which the greater part has now been

lost. He could hardly have been less than

thirty years of age when he came to Milan

with a reputation sufficient to gain commissions

for work in churches; that reputation

must have taken years to acquire, and

must have been associated with very definite

accomplishment. The lack of all record

was essentially the misfortune that beset

men who were not very high in the esteem

of their contemporaries. A painter like

Luini would have executed a great many

pictures for people who could not pay very

well, and had no great gallery or well-built

church to harbour the work, and in the[Pg 54]

course of time the work would tend

inevitably to disappear before the devouring

candle-smoke, or to be carried away

by unscrupulous purchasers who chanced

to be better equipped with taste than

conscience. On the other hand, painters

who led the various movements of their

time would be honoured by successive

generations and their work would be stored

in the best and safest places. To be sure,

fire was never a respecter of palaces or

persons, and the flames have consumed

more work than a collection of the finest

Renaissance pictures in existence could

show, but even then the odds seem to be

in favour of the bigger men because special

efforts would be made to save their paintings

while those of lesser men would be

left with few regrets to take their chance.[Pg 55]

When Luini was engaged to work in

the Church of St. Maurizio there was

a fair chance that his altar-pieces and

frescoes would be well looked after, but

when he worked for a small provincial

family like the Pelucca the house sank

with the family fortunes till at last it became

a farm, and in the early years of the nineteenth

century the frescoes were taken

from the walls with as much care as was

deemed advisable. Doubtless Luini worked

for many men whose worldly position was

not as considerable as that of the Pelucca

family, and that work may have disappeared

altogether. The painter, as we have

seen, did not enjoy the patronage of many

great men before Alessandro Bentivoglio, and

large institutions were not numbered among

his early clients. But he was not altogether[Pg 56]

without valuable patronage in the latter

days, and in the early ’twenties of the sixteenth

century the influential Brotherhood

of the Holy Crown, one of the leading

charitable institutions of Milan, would seem

to have given him some official connection

with their institution; a recognised

position without fixed salary. For them he

painted the magnificent frescoes now in the

Ambrosian Library. The great work there

was divided by the artist into three parts

separated by pillars. In the centre Luini

has depicted the crowning with thorns,

Christ being seated upon a throne while

thorns are being put upon His head; His

arms are crossed; His expression one of

supreme resignation. Above Him little

angels look down or point to a cartouche

on which is written “Caput Regis Gloriæ[Pg 57]

Spinis Coranatur.” In the left hand division

of the fresco and on the right, the fore-ground

is filled with kneeling figures whose

heads are supposed to be portraits of the

most prominent members of the Society.

Clearly they are all men who have achieved

some measure of honour and distinction.

Above the kneeling figures on the left hand

side St. John is pointing out the tragedy

of the central picture to the Virgin Mary,

while on the right hand side a man in

armour and another who is seen faintly

behind him call the attention of a third to

what is happening. A crown of thorns

hangs above the right and the left hand

compartment and there is a landscape for

background. It is recorded that this work

took about six months, and was finished in

March 1522 at a cost to the Society of 115[Pg 58]

soldi. So Luini’s work looks down to-day

upon a part of the great Ambrosian Library,

and it may well be that the library itself will

yield to patient investigation some record,

however simple, of the painter’s life, sufficient

perhaps to enable us to readjust our mental

focus and see his lovable figure more clearly.

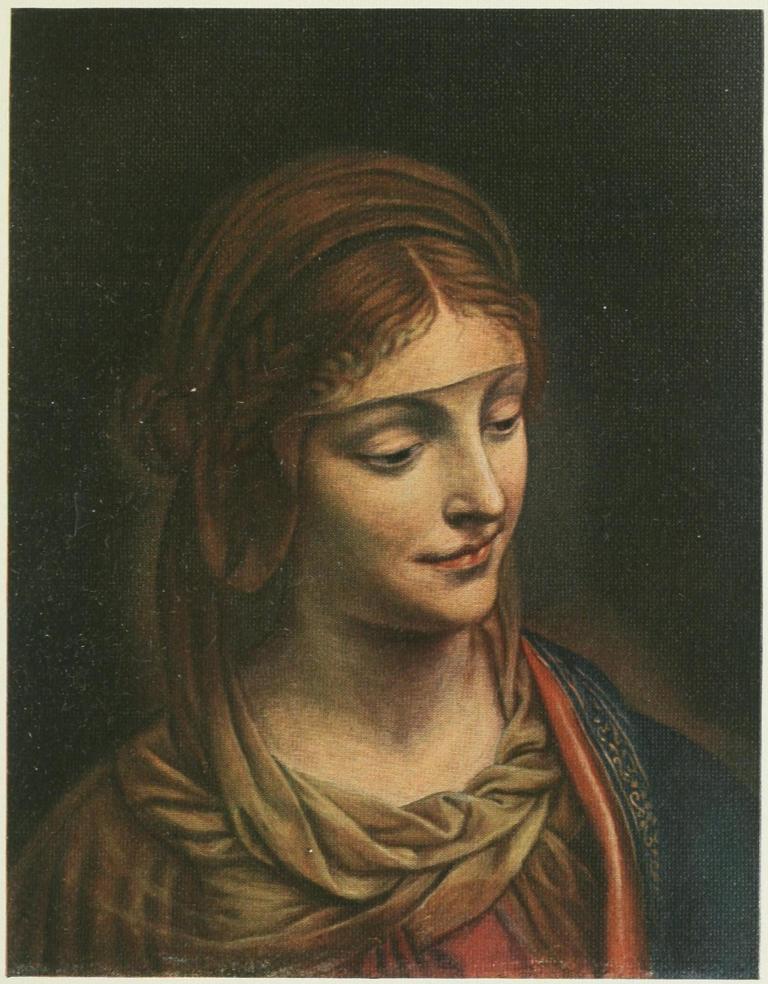

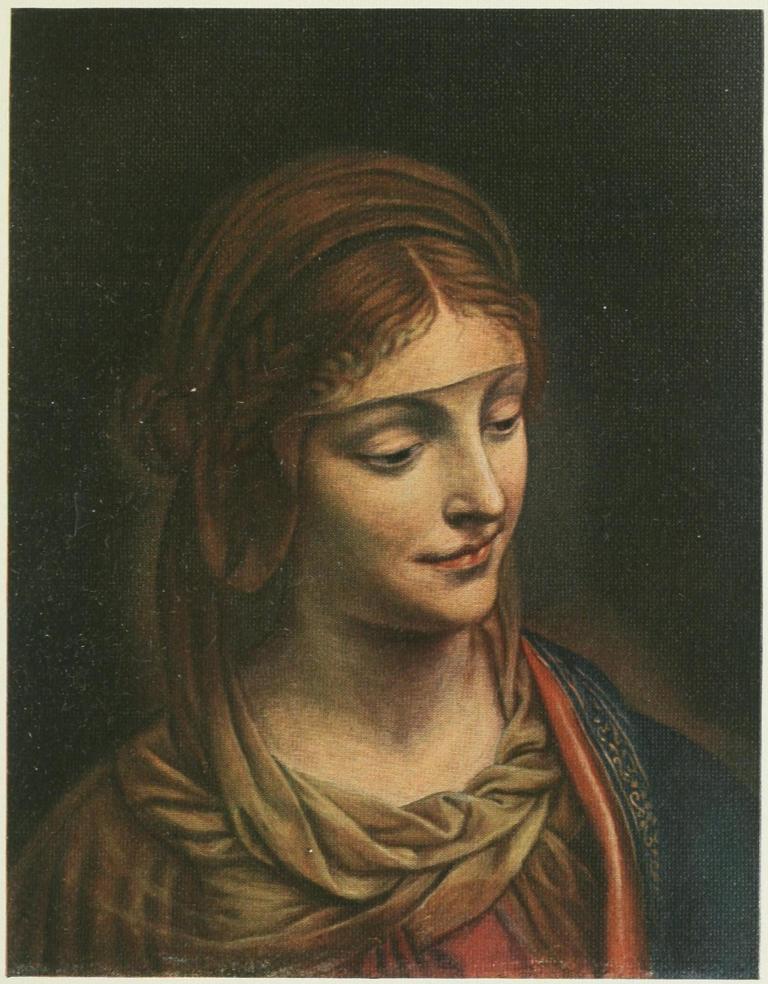

PLATE VII.—HEAD OF VIRGIN

(In the Ambrosiana, Milan)

Here we have another well painted and finely preserved head

painted from one of Luini’s favourite models. The artist must have

known most of the secrets of colour preparation, for his work has

survived much that was painted centuries later. Unfortunately his

frescoes were exposed to the elements and have suffered accordingly.

It may be urged that for those of us

who are content to see with the spiritual

eye Luini is expressed more eloquently by

his work, and particularly by this great

picture in the Ambrosian Library, than he

could hope to be by the combined efforts

of half-a-dozen critics, each with his own

special point of view and his properly profound

contempt for the views of others. The

painter’s low tones and subtle harmonies,

his pure but limited vision, speak to us of a

gentle, refined, and delicate nature, of an

[Pg 61]

achievement that stopped short of cleverness

and consequently limited him to the

quieter byways of artistic life, while those

whose inspiration was less, and whose

gifts were more, moved with much pomp

and circumstance before admiring contemporaries.

The refined mind, the sensitive

soul, shrank from depicting the tragedy of

the Crown of Thorns in the realistic fashion

that would have proved acceptable to so

many other artists. Luini forgets the blood

and the spikes, he almost forgets the

physical pain, and gives us the Man of

Sorrows who has forgiven His tormentors

because “they know not what they do.”

Continental galleries show us many treatments

of the same familiar theme, they have

none to show that can vie with this in a

combination of strength and delicacy that[Pg 62]

sets out an immortal story while avoiding

the brutal realism to which so many other

artists have succumbed. We may suppose

that the objects of the Society roused Luini’s

sympathy to an extent that made it easy

for him to accept the somewhat paltry

remuneration with which the Brotherhood

of the Holy Crown rewarded him, and so

the picture makes its own appeal on the

painter’s behalf, and tells a story of his

claims upon our regard. A man may lie, in

fact it may be suggested on the strength of

the Psalmist’s statement that most men do,

but an artist’s life work tells his story in spite

of himself, and if he labour with pen or brush

his truest biography will be seen in what

he leaves behind him. It is not possible to

play a part throughout all the vicissitudes

of a long career, and no man could have[Pg 63]

given us the pictures that Luini has left

unless he chanced to be a choice and rare

spirit. We may remember here and now

that the time was richer in violent contrasts

than any of its successors, the most

deplorable excesses on the one hand, the

most rigid virtues on the other, seem to

have been the special product of the Renaissance.

While there were men who

practised every vice under the sun there

were others who sought to arrest Divine

Retribution by the pursuit of all the virtues,

and while the progress of the years has to

a certain extent made men neutral tinted

in character, the season of the Renaissance

was one of violent contrasts. On behalf of

the section that went in pursuit of righteousness

let it be remembered that heaven and

the saints were not matters for specula[Pg 64]tion,

they were certainties. Every man

knew that God was in heaven, and that if

the workers of iniquity flourished, it was that

they might be destroyed for ever. Every

man knew that the saints still exerted their

supernatural powers and would come down

to earth if need be to protect a devotee.

Satan, on the other hand, went armed

about the earth seeking whom he might

devour, and hell was as firmly fixed as

heaven. In order to understand Luini, his

life and times, these facts must be borne

in mind. The greater the unrest in the

cities the more the public attention would

be turned to statesmen and warriors, and

when the personalities of artists began to

be considered, those who lived and thrived

in the entourage of popes and rulers monopolised

the attention. Hundreds of men[Pg 65]

were at work earning a fair living and

some local repute, it was left to foreign

favour to set a seal upon success. Had

Luini chanced to be invited to Venice or

to Rome he would have been honoured

throughout Lombardy; but a painter like

a prophet is often without honour in his

own country. Luini’s gifts were of a more

quiet and domestic order than those of his

great contemporaries Leonardo da Vinci and

Michelangelo, for example, were more than

painters, and perhaps it was only in Venice

that painting stood by itself and managed

to thrive alone. Luini would have come

into his kingdom while he lived had Venice

been his birthplace. The genius of the

Florentine school sought to express itself

in half-a-dozen different ways, no triumph

in one department of work could satisfy

men whose longing for self-expression was[Pg 66]

insatiable. In those days it was possible

for a man to make himself master of all

knowledge, literally he could discourse de

omnibus rebus et quibusdam aliis. And

this diffusion of interests was fatal to many

a genius that might have moved to amazing

triumph along one road.

It is clear that Bernardino Luini never

travelled very far from his native country

either physically or mentally. In the eyes

of his contemporaries he was not a man of

sufficient importance to receive commissions

from the great art centres of Italy. This,

of course, may be because he did not have

the good fortune to attract the attention of

the connoisseurs of his day, for we find that

outside Milan, and the little town of Luino

where he was born and whence he took

his name, his work was done in comparatively

small towns like Como, Legnano,[Pg 67]

Lugano, Ponte, and Saronno. Milan and

Monza may be disregarded because we

have already dealt with the work there.

Saronno, which lies some fourteen miles

north-west of Milan, is little more than a

village to-day, and its chief claim upon the

attention of the traveller is its excellent

gingerbread for which it is famous throughout

Lombardy. It has a celebrated church

known as the Sanctuary of the Blessed

Virgin and here one finds some very fine

examples of our painter’s frescoes. Some

of the frescoes in the church are painted

by Cesare del Magno others by Lanini, and

the rest are from the hand of Bernardino

Luini. Round these frescoes, which are of

abiding beauty, and include fine studies

of the great plague saint, St. Roque, and

that very popular martyr St. Sebastian,

many legends congregate. It is said that[Pg 68]

Luini having killed a man in a brawl fled

from Milan to the Church of the Blessed

Virgin in Monza to claim sanctuary at the

hand of the monks. They gave him the

refuge he demanded, and, says the legend,

he paid for it with frescoes. This is little

more than a variant of the story that he

went to Monza under similar circumstances

and obtained the protection of the Pelucca

family on the same terms. In the absence

of anything in the nature of reliable record

this story has been able to pass, but against

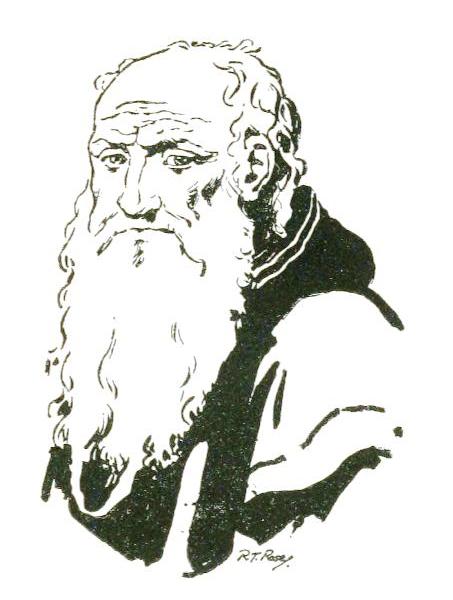

it one likes to put the tradition that one of the

heads in the frescoes is that of Luini himself.

We find that head so simple, so refined, and

so old—the beard is long and the hair is

scanty—and so serene in its expression

that it is exceedingly difficult to believe

that brawling could have entered into the

artist’s life.

PLATE VIII.—BURIAL OF ST. CATHERINE

(In the Brera, Milan)

This is one of the frescoes painted by Luini for the Casa Pelucca

and transferred to Milan in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

It will be seen that although the three angels bearing the Saint to

her grave are obviously peasant girls from the plains of Lombardy

winged for the occasion, the artist has handled his subject with faith

and reverence. The fresco is better preserved than others from the

same house.

[Pg 71]

The subjects of the pictures in Saronno’s

Sanctuary are all biblical. We have an

Adoration of the Magi, showing the same

muddled composition that detracts from the

other merits of the artist’s work; a beautiful

Presentation in the Temple in which the

composition is a great deal better; and a

perfectly delightful Nativity. There is a

Christ is Disputing with the Doctors, and

this is the picture in which we find the

head that is said to be a portrait of the

painter himself. Two female saints figure

in another picture, and Luini’s favourites

St. Roque and St. Sebastian are not forgotten.

Certainly if the monks obtained all

that work at the price of the painter’s safety

they were very fortunate in his choice of

sanctuary.

Como is, of course, a more important

town with large industries and important[Pg 72]

factories, and one of the finest cathedrals

in northern Italy. For the interior Luini

painted another Adoration of the Magi and

another of his favourite Nativities. It is

not easy to speak about the conditions

under which this work was done, and the

inhabitants have so many more profitable

matters to attend to that they do not seem

to trouble themselves about the history of

the painter who helped to make their

beautiful cathedral still more beautiful.

Legnano, with its memories of Frederick

Barbarossa, is within twenty miles of Milan,

and for the Church of San Magno Luini

painted one of his finest altar-pieces. It

is in seven divisions and has earned as

much critical admiration as any work from

the master’s brush.

Lugano is of course in Switzerland, well

across the Italian border. It is a popular[Pg 73]

place enough to-day, and so far as we can

tell, it was the city in which Luini painted

his last pictures. He must have left Milan

about 1528 or 1529, and he would seem to

have gone there to execute commissions,

for in the Church of Santa Maria degli

Angioli we find some of his latest and finest

work. The Crucifixion and the Passion, on

the wall of the screen, contains several hundred

figures arranged in lines in most

archaic fashion. At first sight the work

appears as a mere mass of figures without

any central point in the composition, and

with very little relief for the eye of the

spectator who may come to the church

surfeited with the bewildering riches of

many Italian galleries. But for those who

will take the trouble to study the details

of this fine work there is very much to

admire. In the scene of the picture Christ[Pg 74]

is seen on the cross surrounded by angels.

On his right hand the penitent thief on the

cross is guarded by an angel, while on the

left the impenitent one is watched by a devil

with a curly tail and spiked wings. Below

in perfectly bewildering fashion are many

figures that may be recognised with little

effort—Mary Magdalen, the Madonna,

Joseph of Arimathæa, Roman soldiers, some

of the general public—a confused crowd.

The whole picture is supported by figures

of San Sebastian and St. Roque seen on

either side of the arch. Stories from the

life of Christ are depicted in the upper

parts of the picture, all are painted with

the skill of a great artist and the fervour

of a devotee, but the arrangement is hopelessly

confused. Luini also painted a “Last

Supper” for this church and a “Madonna

with the Infant Christ and St. John.” This[Pg 75]

is signed “Bernardino Luini, anno 1530.”

From 1530 until 1533 the career of the

artist cannot be traced, but in 1533 he was

in Lugano again, and after that year he

passes altogether from our sight. Stray

writers mention his name, some venture to

carry the date of his life into the ’forties,

but we have no proof save their word, no

work to record the later years, and all our

conjecture is vain. It must suffice for us

that Luini’s life as far as his art was concerned

ends for us with the year 1533. If

he lived and worked after that date the

facts relating to the following years and

the work done in the latter days are left

for future students to discover. It is well

to remember that the Saronno portrait

makes the painter look much older than

he is supposed to have been.

To his contemporaries it is clear that[Pg 76]

Luini was a man of small importance. His

best work is seen outside the radius of the

great Art centres of Italy, and it was only

when he attracted the attention of great

critics and sound judges like Morelli, John

Ruskin, and John Addington Symonds that

the lovers of beautiful pictures began to go

out of their way to find his best work in

the little towns whose churchmen were his

patrons. So many of the lesser men had

all his faults—that is to say, lack of perspective

and inability to compose a big

picture—that he was classed with them by

those critics whose special gift lies in the

discovery of faults. The qualities that make

the most enduring appeal to us to-day were

those that were least likely to make a

strong impression upon the strenuous age

of physical force in which he lived. When

great conquerors and men who had accom[Pg 77]plished

all that force could achieve felt

themselves at liberty to turn to prolonged

consideration of the other sides of life they

employed other masters. Then as now there

were fashions in painters. The men for

whom Luini strove were of comparatively

small importance. A conqueror could have

gathered up in the hollow of his hand all

the cities, Milan excepted, in which Luini

worked throughout his well-spent life, and

in the stress and strife of the later years

when great pictures did change hands from

time to time by conquest, Luini’s panel

pictures in the little cities of his labours

passed quite unnoticed, while even if the frescoes

were admired it was not easy to move

them. When at last his undoubted merits

began to attract attention of connoisseurs,

these connoisseurs were wondering why

Leonardo da Vinci had left such a small[Pg 78]

number of pictures. They found work that

bore a great resemblance to Leonardo and

they promptly claimed that they had

discovered the lost masterpieces. Consequently

Leonardo received the credit that

was due to the man who may have worked

in his Milanese school and was undoubtedly

under his influence for a time. And many of

the beautiful panel pictures that show Luini

at his best were attributed to Leonardo

until nineteenth-century criticism proved

competent enough to render praise where

it was due, and to say definitely and with

firm conviction that the unknown painter

from Luino, who lived sometime between

1470 and 1540, was the true author.

If, in dealing with the life of Bernardino

Luini, we are forced to content ourselves with

meagre scraps of biography and little details

that would have no importance at all in deal[Pg 79]ing

with a life that was traceable from early

days to its conclusion, it is well to remember

that the most important part of the great

artist is his work. Beethoven’s nine symphonies,

Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” the landscapes

of Corot, the portraits of Velazquez,

and the carving of Grinling Gibbons are

not more precious to us because we know

something of the life of the men who did

the work. Nor are the “Iliad” and the fragments

that remain of the works of the

great Greek sculptors less to us because a

shadowy tradition is all that surrounds the

lives of the men who gave immortal work

to the world. We must remember that it

is as difficult to deal with art in terms of

literature as it is to express the subtle

charm of music in words. Had Luini’s years

boasted or regretted a series of gossiping

newspapers we should have gathered a[Pg 80]

rich harvest of fact, but the facts would

have left the painter where he is. There

is enough of Luini left in Milan and the

smaller places we have named to tell us

what the man was and the spirit in which

he worked, and while we will welcome the

new-comer who can add to our scanty

store of authenticated facts we can hardly

expect that they will deepen our admiration

of work that for all its shortcomings

must be remembered when we turn to

ponder the greatest achievements of Italian

Art. It forms “a magic speculum, much

gone to rust, indeed, yet in fragments still

clear; wherein the marvellous image of his

existence does still shadow itself, though

fitfully, and as with an intermittent light.”

The plates are printed by Bemrose Dalziel, Ltd., Watford

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 42163 ***