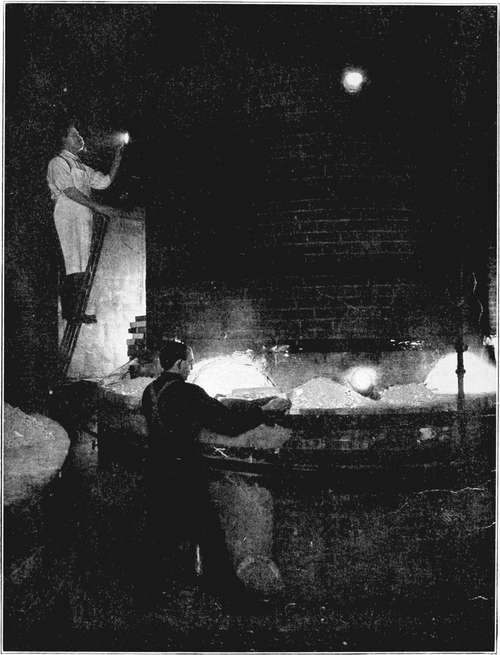

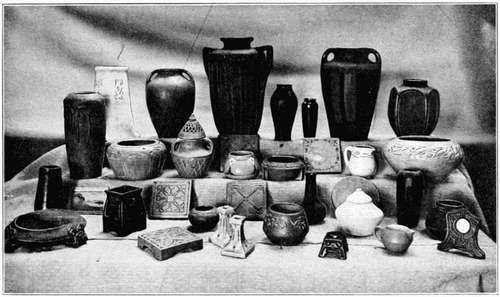

Courtesy of the Rookwood Potteries

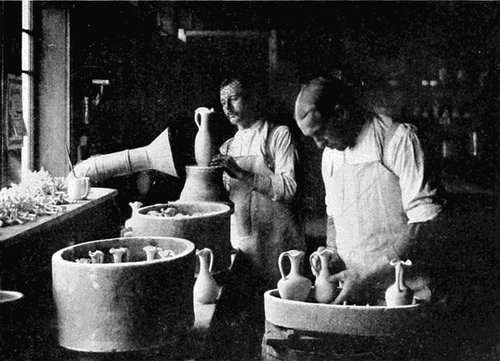

Firing the Kiln

Courtesy of the Rookwood Potteries

Firing the Kiln

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION SERIES

SUPERVISING EDITOR

FRED D. CRAWSHAW, M.E.

Professor of manual arts, the university of Wisconsin

A TEXTBOOK OF PRACTICAL METHODS FOR STUDENTS,

TEACHERS, AND CRAFTSMEN

BY

WILLIAM H. VARNUM

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF DRAWING AND DESIGN

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN

SCOTT, FORESMAN AND COMPANY

CHICAGONEW YORK

Copyright 1916 by

Scott, Foresman and Company

Place for the Book. As a textbook, Industrial Arts Design is a practical guide for designing in wood, clay, and base and precious metals. It is intended for individual student use in the High Schools, Normal Schools, and Colleges and as a reference book for elementary school teachers. Its more complex problems are intended as definite helps to the industrial arts designer or craftsman. The wood problems are treated with special reference to their adaptability to bench and cabinet work.

Need of the Book. It has been written to fill a decided demand for a textbook that shall, without loss of time, directly apply well-recognized principles of general design to specific materials and problems encountered in the Industrial Arts. A brief description of the decorative processes adapted to the materials under discussion with the design principles directly applying to these processes, insures designs that may be worked out in the studio or shop. It is hoped that this provision will eliminate the large number of impractical designs that are frequently entirely unfitted to the technic of the craft. This lack of mutual technical understanding between the teacher of design and the shop work instructor is the cause of friction that it is hoped will be removed by the methods advocated in these pages.

The Author's Motive. It has been the intention to reduce unrelated and abstract theories to a minimum and reach directly rules and conclusions that shall be applicable to typical materials in common use in the schools and industries. The original conception materialized in the publication of a series of articles upon Design in the Industrial Arts Magazine, in 1915. These articles were favorably received and their results in the schools proved highly satisfactory. Through this encouragement, the articles have been reprinted in book form, enriched by the addition of illustrations, review questions, and three chapters on color with its applications.

Industrial Arts Design develops the principles of industrial design in a new and logical form which, it is believed, will simplify the teaching of craft design. Chapters I to V deal with the elementary problems confronting the designer as he begins the first steps on his working drawing; Chapters VI to VIII show the methods by which he may express his individuality through contour or outline enrichment, while Chapters IX to XVII explain the treatment of the most difficult form of decoration, that of surface enrichment.

The Appendix. The appendix is added to show the manner in[4] which the rules may be directly applied to a course of study in either pottery or art metal. The present work is not intended to include the chemistry of glaze mixing or other technical requirements to which reference is made in the appendix; consequently the reader is referred to "The Potter's Craft" by C.F. Binns and "Pottery" by George J. Cox for fuller explanations of the formulae and technicalities of the craft.

Source of Principles. The principles herein advocated are directly related to architectural design which is to be regarded as the standard authority for the industrial arts designer. It was necessary to state these principles in the form of sufficiently flexible rules which would allow the student to use his own judgment, but at the same time, restrict him to the essential principles of good design.

Rules. This presentation of the principles of design by means of flexible rules in concrete form, serves to vitalize design by virtue of their immediate application to the material. The rules likewise save time for both pupil and instructor. This is regarded as an important factor, inasmuch as the amount of time usually allotted to classroom teaching of design is limited.

While these rules are applied to the specific materials, the designer may readily adjust them to other materials and find them equally applicable. Direct copying of designs from the illustrations is a dangerous expedient and is to be discouraged as a form of plagiarism which will eventually destroy the student's initiative, originality, and reputation for creative work.

Results. From the tests so far observed, it has been seen that under design guidance, the projects become more noticeably individual in character, lighter and better in construction, and more fully adjusted to their environment. The student's interest and initiative in his work are strengthened, and he completes the truly valuable cycle of the educative process of evolving his own idea and crystallizing it in the completed work. It is hoped that this book will tend to develop higher standards of good design in schools, industrial establishments, and the home.

In conclusion, the author expresses his thanks to the following for their valuable suggestions and assistance in contributed illustrations: Miss D.F. Wilson, Miss Edna Howard, Miss Elizabeth Upham, Miss A.M. Anderson, Mr. J.M. Dorrans, Mr. J.B. Robinson, author of "Architectural Composition," and others to whom reference is made in the text.

William Harrison Varnum.

Madison, Wisconsin.

April, 1916.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Divisions of Industrial Arts Design | 7 |

| II. | The Primary Mass and Its Proportions | 13 |

| III. | Horizontal Major Divisions of the Primary Mass | 19 |

| IV. | Vertical Major Divisions of the Primary Mass | 33 |

| V. | Appendages and the Rules Governing Them | 43 |

| VI. | Enrichment of the Contours or Outlines of Designs in Wood | 57 |

| VII. | Enrichment of the Contours or Outlines of Designs in Clay | 77 |

| VIII. | Enrichment of the Contours or Outlines of Designs in Base and Precious Metals | 87 |

| IX. | Surface Enrichment of Small Primary Masses in Wood | 99 |

| X. | Surface Enrichment of Small Primary Masses in Wood. (Continued) | 117 |

| XI. | Surface Enrichment with Minor Subdivisions of Large Primary Masses in Wood | 133 |

| XII. | Surface Enrichment of Clay | 145 |

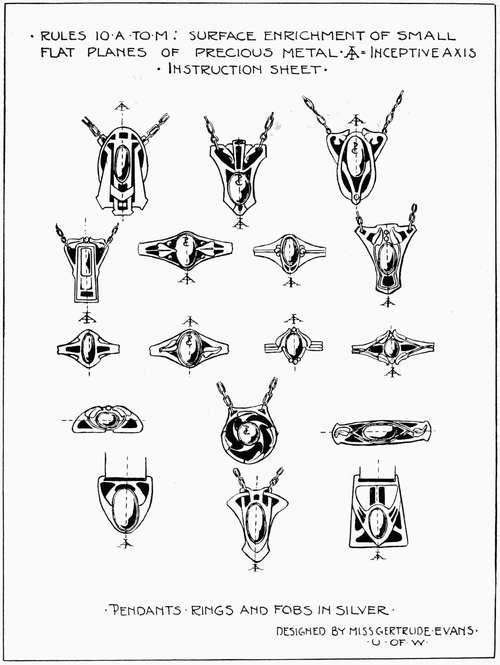

| XIII. | Surface Enrichment of Precious Metals. Small Flat Planes | 160 |

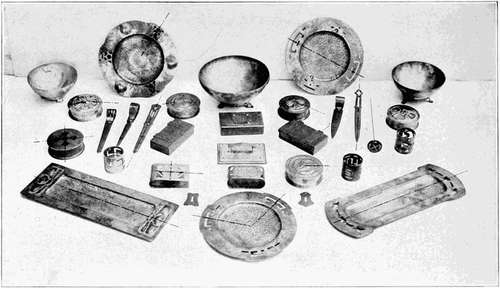

| XIV. | Surface Enrichment of Large Primary Masses in Base and Precious Metals | 179 |

| XV. | Color: Hue, Value, and Chroma; Stains | 194 |

| XVI. | Color and Its Relation to Industrial Arts Design. Large Surfaces of Wood; Wall and Ceiling Areas | 201 |

| XVII. | Color and Its Relation to Industrial Arts Design. Small Surfaces in Clay and Metal | 209 |

| Complete Summary of Rules | 218 | |

| Appendix | 223 | |

| (a) A Complete Course of Study for the Applied Arts in Thin Base and Precious Metals. Relation of the Rules to the Problems | 224 | |

| (b) A Complete Course of Study for the Applied Arts in Pottery. Relation of the Rules to the Problems | 237 | |

| Index | 245 |

INDUSTRIAL ARTS DESIGN

This book has been written with the view of presenting design from the standpoint of the industrial arts. An instructor generally experiences difficulty in finding the exact word to use when criticizing a student's drawing. The student has equal difficulty in understanding the criticism. There is little wonder that he is confused, when the rather ambiguous terms "good-looking," "ugly," "squatty," and "stiff" are used to express qualities that can be expressed only in terms of design.

The lack of understanding between the pupil and the teacher may be compared to the attitude of the average individual "who knows what he likes." He is on an equally insecure footing regarding industrial design. His reason for liking or disliking a certain thing may depend upon some whim or fancy, the popular fashion of the times, or a desire to possess a duplicate of something he has seen. As a consumer with purchasing power, he should have the ability to analyze intelligently the contents of catalogs and store windows with the thought of securing the best in industrial art—something that may be accepted as standard one hundred years from now.

It is, therefore, the intention to present design of industrial character in its simplest form, freed from technicalities or ambiguous statements. It is intended to give the average individual not particularly interested in drawing or design a knowledge of the subject, based upon principles that have survived for hundreds of years in architectural monuments and history.

It is possible that the presentation of these principles may enable the instructor in the public schools to guide his pupil away from the heavy and expensive stereotyped designs, and by clear and simple criticism, lead him to better forms of construction. He may also be [9] helped to lead the pupil to design problems in harmony with his home surroundings and thus avoid the introduction of an inharmonious element into what may possibly be a harmonious setting. The teacher, pupil, or layman should use his knowledge of the subject as a basis for criticism or appreciation of the field of the industrial arts.

In order to start successfully upon a design, it is necessary to know what qualities a good industrial article should possess. Whether one is designing a bird-house, a chocolate set, or a gold pendant, the article must meet three needs: (1) It must be of service to the community or to the individual; (2) It must be made of some durable material; (3) It must possess beauty of proportion, outline, and color.

Ruskin said that a line of beauty must also be a line of service. The "stream line body" in automobile construction is the result of the automobile maker's attempt to combine beauty with service. This is the attitude that should govern the union of beauty and service in all of the industrial arts.

There are three divisions or phases in the designing of a structure and its enrichment. These are: (1) Structural Design; (2) Contour Enrichment; (3) Surface Enrichment. Some objects are carried through only one of these divisions, while others are developed through all three of them.

Plate 1, illustrative of the first division, deals naturally enough with the planning of the constructive or utilitarian lines of an object and its parts. It may be termed Structural or Constructive Design. Questions of how high or how long an object should be, to harmonize with its width, the proper placing of rails, shelves, and brackets, the determination of the greatest and least diameter of vase forms have to be decided in this period of Proportions and Space Relations.

The knowledge of tools and materials, and of the manner in which they may be used for constructive purposes, influences the solution of these questions and others which we shall shortly discuss. Strictly utilitarian objects are seldom carried past this stage of development.

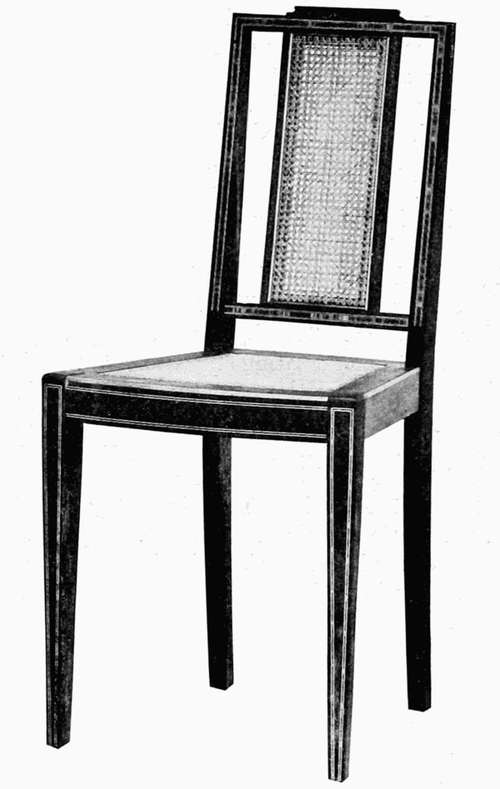

Plate 2 indicates the next logical division—Contour Enrichment—or the period of the enrichment of the structural outline or contour. The bounding lines, or contours, of the structure may be enriched in many ways, as, for example, curving certain portions to soften the severity of the plain structure. The garden urn and small stool have contours treated in this manner. Chippendale, Sheraton, and Hepplewhite furniture, simplified to the accepted range of shop technic, vary the straight lines of mission furniture and come within the possible developments of this division.

The cement fence post at C, Plate 2, is a strict utilitarian problem without interest. The post at D, enriched by a bevel, has equal utilitarian and increased aesthetic interest and value.

Plate 3 illustrates the last division of evolution and concerns itself with the application of design to the surface of the otherwise complete structure. This division is commonly called applied surface design or decorative design. It is readily seen that this division should be considered after the structure has been carefully planned. To separate this division from the period of structural or contour enrichment we will call it Surface Enrichment.

It may be seen from the foregoing discussion that a design may be carried through the following steps: (1) Blocking in the enclosing lines of the design, as at Figure B, Plate 2, adding to this whatever may be needed for structural purposes, keeping the lines as nearly vertical and horizontal as possible; (2) Enriching and varying the outline or contour. It is well for elementary wood workers to use this step with extreme caution, while less reserve is necessary in clay and metal; (3) After careful consideration in determining the need of additional decoration, the last step, surface enrichment, should be used. The following chapters will take up these steps in the order stated above.

The ideal method of developing the principles set forth in this chapter includes correlated activity in the shop by working out the project in the required material. As the technic of the individual improves, the larger range of design principles will be found to accompany and parallel his increasing skill.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. What three requirements should be met in a well designed industrial article?

2. State three major divisions in industrial arts design.

3. State briefly the problems to be considered in each division.

4. What is the last and ideal step for the designer?

Upon first observing a building, one seldom notices details of structure. He sees the large mass as it is silhouetted against the sky. Nearer approach discloses mouldings, cornices, and doorways; while careful analytical study shows the technical points of construction. The architect, in his original planning, thinks in terms of masses, widths, and heights, disregarding at first the details and color. As architecture stands for parent design principles and represents some of the world's best examples of composition and design, industrial design should be based upon the best examples of architectural design. To a certain degree, also, the methods of the industrial arts designer should be those of the architect.

It is necessary to think at first of our problem as a single mass or solid, bounded by enclosing dimensions of width, height, and thickness. Details like a mirror, handles, brackets, or knobs may project outside of this mass, but for the time being, they may be disregarded. Figure B, Plate 2, shows this manner of thinking, and will enable us to regard the problem as a big, simple mass so that the entire object, unobstructed by small details, may be seen.

This is the method of thinking about the problem which should precede the drawing. To further describe this mass, which will be called the single or Primary Mass, it is necessary to think of the intended service of the project. A rather hazy idea of making a vase or a stool to be put to no particular use, may have been the original motive. Now the exact service should be defined as it will have a marked effect upon the shape of this primary mass.

Rule 1a. A primary mass must be either vertical or horizontal according to the intended service, unless prohibited by technical requirements. Service is an important factor inasmuch as it limits the intended use of the mass. A mass is horizontal when its largest dimension is horizontal. When the horizontal dimension of this [15] mass is reduced until the main vertical dimension is longer than the main horizontal one, it becomes a vertical mass. As an example, a davenport is generally a horizontal mass intended to hold a number of people. When the mass is narrowed to the point where the vertical dimension exceeds the horizontal, it becomes a chair for one person. A low bowl may be intended for pansies, but as soon as the service changes and we design it for goldenrod, it becomes a vertical mass. The fable of the fox who, upon being invited to dine with the stork, found the tall vases unfitted for his use illustrates the change of mass with the change of service.

Figures 1 and 4, Plate 4, are examples of horizontal masses with the dark lines indicating the dominance of the horizontal lines and planes. The shelter house contains a long bench, making necessary the long horizontal lines of the building. The calendar holder has to be a horizontal mass because of the restrictions imposed by the shape of the calendar pad.

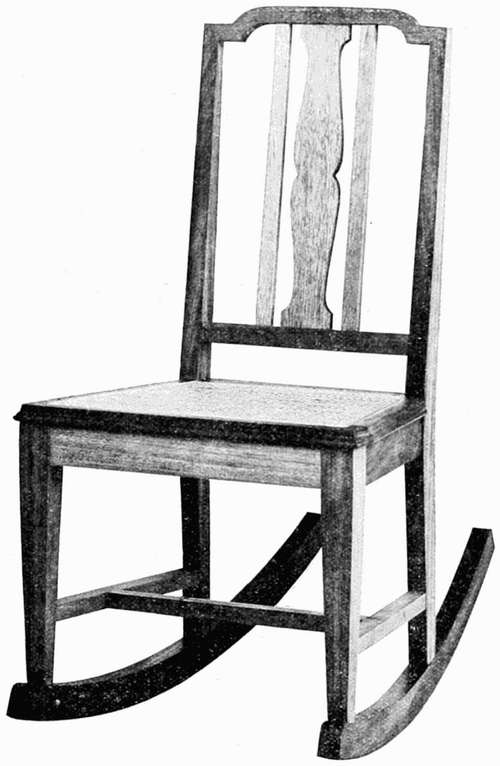

Figures 2 and 3 are vertical masses. The vase is intended for tall flowers, while the chair, as has already been mentioned, must meet the needs of a single person. Utility and service then have been found to give the primary mass a given direction or dominance.

The designer now represents this mass by drawing a rectangle similar to the block outline of Figure B, Plate 2. It is now necessary to see if the foundation stones of this rectangle have been laid correctly; in other words, to test the proportions of the primary vertical or horizontal mass.

Rule 1b. A primary mass should have the ratio of one to three, three to four, three to five, five to eight, seven to ten, or some similar proportion difficult for the eye to detect readily and analyze. Proportions are generally expressed in terms of ratios. A surface of five by eight inches would give a ratio of five to eight; ten by sixteen feet is reducible to the same ratio. Certain ratios are monotonous and offend the eye by their lack of variety. Ratios such as one to one or one to two are of this class and should be avoided. If these ratios could speak they would resemble people talking in a low monotonous tone of voice.

Certain other ratios are weak and indeterminate, showing a lack of clear thinking. They are like people with no definite or cleancut [17] ideas upon a subject they discuss. Examples in this class show ratios of two to two and one-eighth, or three to three and one-fourth, neither positively square nor frankly rectangular. They hide around the corner, as it were, waiting to be anything. Figure 5, Plate 5, is an example of unsatisfactory proportionate ratios of the primary mass. The blotting tablet is nearly square, while the candlestick and sconce, which should have been designed with strongly vertical masses, lack the type of definite thinking that results in a decided vertical dimension.

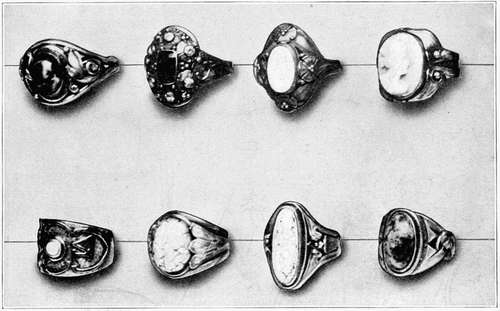

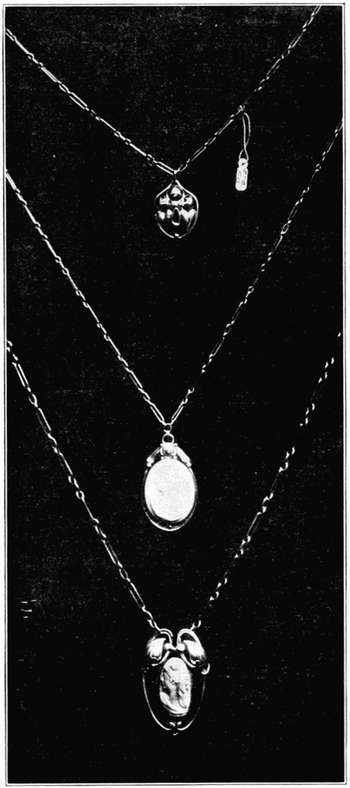

Disregarding the improvement in technic, Figure 6 shows problems designed with a definite knowledge of proportion. The metal objects are refined in their dimensions, and pleasing to the eye. Tests have been made with the idea of determining what the eye considers perfectly natural and agreeable proportion. This has been found to be the ratio of two to three. Consequently, it is clear why Figure 6 shows objects more pleasing than those in Figure 5.

It may be felt that too much space is being given to this subject of proportion. It should be remembered, however, that the industrial arts are intimately associated with daily life and that unless proportions are pleasing to our aesthetic sense, many articles of common use shortly become intolerable.

This preliminary portion of the designer's task has been given to thinking out the problem and drawing one rectangle. There is a tendency to start the design by pushing the pencil over the paper with a forlorn hope that a design may be evolved with little mental effort. This should be regarded as illogical and unworthy of the desired end. A rectangle of the most prominent surface of the problem, based upon the desired service of the project, and the best proportions which our knowledge of design and understanding of the limitations of construction will permit, should be the final result of the first study. From now on through the succeeding steps, the details of the problem will become more and more clear, as the technical limitations of the tools and materials governing the designer's ideas and controlling and shaping the work are better understood, until all governing factors become crystallized in the form of a working drawing or model. This is a strictly professional practice as illustrated in Figure 7, which shows the skilled Rookwood potter[18] developing a vase form, the definite embodiment of correct thinking in terms of the material which is constantly before him.

SUMMARY OF RULES

Rule 1a. A primary mass must be either vertical or horizontal according to the intended service, unless prohibited by technical requirements.

Rule 1b. A primary mass should have the ratio of one to three, three to four, three to five, five to eight, seven to ten, or some similar proportion difficult for the eye to readily detect and analyze.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. How does the architect first plan his elevations?

2. How should the designer first think of his problem?

3. Define a horizontal primary mass.

4. Define a vertical primary mass.

5. State some desirable ratios to be used in designing the proportions of the primary mass. Explain.

In the second chapter we discussed the nature of the primary mass in its relation to the intended service or duty it has to perform. It was found that the demands of service usually cause the primary mass to be designed with either a strong vertical or horizontal tendency.

It now becomes imperative to carry the designing processes still further and divide the vertical or horizontal primary mass into parts or divisions, demanded either by structural requirements or because the appearance of the object would be materially improved by their presence. This latter point is sometimes referred to as the aesthetic requirement of the problem. There are two simple types of divisions, those crossing the primary mass horizontally and those crossing the primary mass in a vertical direction. This chapter will be limited to the subject of horizontal divisions.

If a city purchases a piece of land for park purposes, presumably a landscape architect is assigned the task of laying out the paths and drives. He does this by crossing his plan at intervals with lines to represent paths connecting important points. Under favorable conditions the architect is free to curve his path to suit his ideas. He has considerable freedom in selecting his design but the paths or roads must dip and curve in sympathy with the contour of the land and in accord with the aesthetic requirements.

While the landscape designer has a broad latitude in his treatment of land divisions, the industrial designer or architect is restricted, on the other hand, by the structural requirements of the object and by his materials. He must cross his spaces or areas by horizontal shelves, or rails, or bands of metal that hold the structure together. As architecture is of fundamental importance in industrial design, let us see what the architect has in mind in designing a structure.

The architect has the surface of the ground with which to start. This gives him a horizontal line as the base of his building. He considers it of major importance in his design. We find him crossing the front of his building with horizontal moulding or long bands of colored brick, paralleling the base line and otherwise interestingly dividing the vertical face of the front and sides. His guide is the bottom line of his primary mass or the line of the ground which binds the different parts of the building into a single unit. It can be readily seen that if he shifted the position of his mouldings up or down with the freedom of the landscape architect in locating his roads, he would not be planning his horizontal divisions in sympathy with the structural requirements of his primary mass.

These horizontal divisions or lines have a tendency to give apparent added length to an object. Thus by their judicious use a designer may make a building or room look longer than it really is.

Let us now turn to the simpler objects with which we may be more directly concerned. The piano bench has horizontal lines crossing it, giving an effect quite similar to that of horizontal mouldings crossing a building. There may also be ornamental inlaid lines crossing the bench and intended to beautify the design, but it is to be remembered that at present we are considering the structural divisions only.

Plate 6 represents a concrete example of the methods to be used in designing the horizontal divisions of a piano bench. The steps may be divided as follows:

(a) The height of a piano bench may be determined either from measurement of a similar bench or from one of the books on furniture design now on the market. The scale of one inch or one and one-half inches to the foot may be adopted. Two horizontal lines should be drawn, one for the bottom and one for the top of the bench. The distance between these lines we will arbitrarily fix at twenty inches.

(b) Many objects are designed within rectangles which enclose their main or over-all proportions. With this in view, and keeping in mind the width of the bench necessary to the accommodation of two players and the requirements of a well proportioned primary mass (Rule 1b), the lines are now drawn completing the rectangular [23] boundaries of the primary mass. The limitations of service and the restrictions of good designing give the width of the primary mass so designed as three feet and two inches, with a ratio of height to length of five to eight and one-half. It is simpler to design first the most prominent face of the object to be followed by other views later in the designing process.

(c) By observing benches similar to the one being designed it will be seen that the horizontal divisions will take the form of a rail and a shelf, making two crossings of the primary mass dividing it into three horizontal spaces. Several trial arrangements of these structural elements are now made with the thought of making them conform to the rule governing three horizontal spaces. Rule 2b. We shall later discuss this rule and its applications fully.

(d) By selecting the best sketch of many which the designer will make he has the basis for the application of Rule 2b for the structural elements. The project now begins to take on concrete form. The top board may project slightly beyond the primary mass without materially affecting the value of the designed proportions.

(e) The last step is the designing of the side view in relation to the front view. This enables the designer to comprehend the project as a whole. It is strongly urged that the final or shop drawing be of full size. In more elaborate designs the finer proportions are lost in the process of enlargement from a small sketch, often hurriedly executed in the shop. Again much time is lost by necessary enlargement, whereas a full size curved detail may be quickly transferred to wood by carbon paper or by holes pricked in the paper. It is not expensive or difficult to execute full size drawings; it is in accord with shop practice and the custom should be encouraged and followed on all possible occasions. See Figure 102a.

The process of designing round objects is identical to that just described as illustrated by the low round bowl in Plate 7. It should be designed in a rectangle of accepted proportions. Rule 1b. The primary mass may have excellent proportions and yet the vase or bowl may remain devoid of interest. It may be commonplace.

As will shortly be shown, the rules governing horizontal divisions serve as a check on the commonplace. A horizontal division generally marks the point where the outward swell of the vase contour [25] reaches its maximum width. If this widest point in the primary mass (X-Plate 7) is pleasingly located between the top and bottom of a vase form the contour will be found satisfactory.

It is possible to continue ad infinitum with these illustrations but horizontal space divisions are nearly always present in some form, due to structural necessity or aesthetic requirements. It is an easy matter to say that these lines must divide the primary mass into "interesting" spaces, well related to each other, or "pleasingly located," but the designer must have some definite yet flexible rule to govern his work. From the analysis of many famous historic buildings and well designed industrial projects it has been found that all horizontal masses may be analyzed as dividing the primary mass into either two or three divisions or spaces, regardless of the complexity of the project.

Rule 2a. If the primary mass is divided into two horizontal divisions, the dominance should be either in the upper or the lower section. Plate 7 shows this division of the primary mass—the simplest division of the space. A space divided just half way from top to bottom would be monotonous and expressive of the ratio of one to one. This arrangement as we have already discovered in the second chapter is not conducive to good design.

By the stated rule, 2a, the varied adjustment of this double horizontal division affords all possible latitude for constructive purposes. It is better to place the division in such a manner that the upper division (or lower) will not appear pinched or dwarfed by comparison with the remaining area. Thus a ratio of one to three, or three to five, or five to eight is better than a ratio of one to one or one to eighteen, but there is no exact or arbitrary ruling on this point.

Figure 8 illustrates two horizontal divisions in wood construction and also the freedom of choice as to exact proportions. The eye will be found a good judge of the proper spacings subject to the limitations already mentioned.

It is best to keep the design within the limits of two horizontal [27] space divisions in designing cylindrical clay forms, particularly in the elementary exercises. Enough variety will be found to make pleasing arrangements, and the technical results obtained by two divisions are much better than those obtained from a greater number of divisions.

Figures 14, 15, and 16, Plate 9, are clay forms with the dominance placed in either the upper or lower portion of the primary mass. Figure 13 has been used to illustrate the fact that horizontal space division principles are applicable to any material. The horizontal divisions in Figure 13 are due to structural needs. A horizontal line carries this division across to Figure 14, a clay vase. The horizontal division line now becomes the one which marks the widest part of the vase. It gives the same relation between the top and bottom horizontal spaces as in Figure 13. It marks an aesthetic point in the design of the vase, or a variation of the contour, introduced by reason of its effect upon the beauty of the vase, not called for by the needs of actual service.

A musical composition is often played in an orchestra first by the wood instruments, taken up and repeated by the brasses, then by the strings, and finally played as an harmonious whole by the entire orchestra. There is a close parallel in Figure 12, an adaptation of one of Gustav Stickley's designs. The two-division rule is used in the relations of the plaster and wainscoting; again in the plaster over, and the cement or tile around the fireplace. It is repeated in the arrangement of the copper and cement of the fireplace facing and hood and in the door panels. By repeating again and again similar space divisions the wall space becomes a unified and harmonious whole. Variety is secured by the introduction of three horizontal divisions in the details of the wainscoting. This method of repeating similar space divisions is called "echoing" and is one of the most effective means known for securing the effect of unity.

The horizontal subdivisions in metal are usually made for service. Figures 17, 18, and 19, Plate 10, are examples of such divisions. The location of the clock face in Figure 18 calls for the placing of its horizontal axis in accordance with Rule 2a. The lamp in Figure 19 shows an instance where the entire design once divided by Rule 2a, may be again subdivided into a similar series of divisions. This [29] arrangement is quite similar to the system of repetitions seen in Figure 12 and termed "echoing" the original divisions.

Rule 2b. If the primary mass is divided into three horizontal divisions or sections, the dominance should be placed in the center section with varying widths in the upper and lower thirds.

When it becomes necessary to divide the primary mass into more than two sections the designer's problem becomes more difficult. With the addition of a greater number of horizontal divisions there is a manifest tendency for the design to become cut up into so many small sections that the simplicity of the whole mass is lost. Here, as elsewhere, that principle which we call unity or the quality of "holding together" is necessary and should be the constant test of the design. The instant any part of the design seems to fly apart from the main mass it becomes the designer's duty to simplify the design or pull the parts together and thus restore the lost unity.

As a restriction against loss of unity it is necessary to group all of the minor horizontal divisions into a system of two or three large horizontal divisions. Referring to Rule 2b, it is seen that when three divisions are used, it becomes the practice to accentuate the center section by making it larger. This arrangement is designed to give weight to the center portion and by this big stable division to hold the other subdivisions together and in unity.

Two horizontal masses and one vertical mass shown in Figures 9, 10, and 11, Plate 8, illustrate the application of this three-division rule to wood construction. It is seen that the construction of rails, doors, and shelves is responsible for the fixing of all of these divisions. It may also be seen that three divisions are applicable to either the vertical or the horizontal primary mass. Figure 10 illustrates the violation of this type of spacing at the point A, where the shelves are no more pleasingly arranged than the rounds of a ladder. Later on we shall be able to rearrange these shelves in a pleasing manner but at present it is better to relieve the monotony by omitting the center shelf. This applies the three division rule to the satisfactory appearance of the desk at B.

Similar monotony in spacing is seen in the screen, Figure 11. The correction in B appeals at once as a far more satisfactory arrangement than that secured by placing the cross bar half way up as in A.[30] There are no infallible rules for this readjustment beyond those already stated. The eye must in part be depended upon to guide the artistic sense aright.

It is suggested that it is desirable to keep clay forms within the limitations of two divisions. Rectangular posts, pedestals, and other vertical forms in cement may be developed by the application of Rule 2a or 2b, if care is taken to group all minor divisions well within the limitations of these rules.

The statement just made in reference to simplified groupings is illustrated in the candlestick and cup in Figures 20 and 21, Plate 10. The construction based upon the three functions performed by the cup, the handle, and the base, suggests the use of these horizontal divisions. The minor curves have been subordinated to, and kept within, these three divisions. The final result gives a distinct feeling of unity impossible under a more complex grouping. The Greek column will afford an architectural illustration of a similar grouping system.

The lathe bed of Figure 22 shows one of innumerable examples of space violations in the industrial arts. A slight lowering of the cross brace would add materially to the appearance and strength of the casting. Figure 23 is a copper box with the following more or less common faults of design: commonplace ratio of length and width (2:1) partially counteracted, however, by a more pleasing ratio of the vertical dimension, equal spacing in the width of cover of box and box body, and equal spacing of the hinges of the box from the ends of the box and from each other. By applying the two and three horizontal division rules these errors may be avoided.

Figure 24 shows a low bowl with a compass curve used in designing the contour. This has brought the widest part of the design in the exact center of the bowl which makes it commonplace. In addition to this the top and bottom are of the same width, lacking variety in this respect. Correction is readily made by applying a freehand curve to the contour, raising or lowering the widest point (F), at the same time designing the bottom either larger or smaller than the top.

INSTRUCTION SHEET

Plate 7 is a sheet suggestive of the application of Rules 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b, with an indication of the type of problem to be required. The steps of the designing processes in either wood (class 1), clay (class 2), or metal (class 3), are summarized as follows:

SUMMARY OF DESIGN STEPS

(a) Construction of the rectangle representing the vertical or horizontal character of the primary mass with desirable proportions. It is better to select a typical view (Plate 6, D), preferably a front elevation.

(b) Subdivide this rectangle into two or three structural sections; horizontal in character. Make two or three trial freehand sketches for varied proportions and select the most pleasing one in accordance with Rules 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b.

(c) Translate the selected sketch to a full size mechanical drawing or at least to a reasonably large scale drawing. The structural elements: i.e., legs, rails, posts, etc., should be added and other additional views made.

(d) Dimension and otherwise prepare the drawing for shop purposes.

(e) Construct the project.

SUGGESTED PROBLEMS

Design a nasturtium bowl, applying Rules 1a, 1b, 2a. Design a writing table 2 feet 6 inches high with three horizontal divisions.

SUMMARY OF RULES

Rule 2a. If the primary mass is divided into two horizontal divisions, the dominance should be either in the upper or the lower section.

Rule 2b. If the primary mass is divided into three horizontal divisions or sections, the dominance should be placed in the center section with varying widths in the upper and lower thirds.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. State two methods of subdividing the primary mass.

2. Define the nature and need of horizontal space divisions.

3. Give five steps to be used in designing a foot stool or piano bench.

4. What point constitutes a horizontal division in the contour of a simple clay bowl?

5. State the rule governing two horizontal space divisions and furnish illustrations in wood, clay, and metal.

6. Give the rule governing three horizontal space divisions and supply illustrations in wood, clay, and metal.

7. State five steps in the designing of a project in the industrial arts involving the use of horizontal structural divisions.

The design of the primary mass has now been considered under Rules 1a and 1b, and its horizontal divisions under Rules 2a and 2b. The next logical step is the consideration of the nature of the lines that cross the primary mass in a vertical direction. In the original planning of the primary mass it was found that the horizontal bounding lines and the horizontal divisions were parallel to the base line of an object and that the base line was necessary to ensure stability. Vertical lines are necessary and equally important to give the needed vertical support to an object.

So accustomed is the eye to vertical lines in tree trunks, tall buildings, and thousands of other examples that the upward eye movement in viewing an object, having a predominance of vertical elements, seemingly adds to its height.

The designer thus has a most useful device with which to increase the apparent height of an object that, for structural or other reasons, must in reality not have great height. Chapter III drew attention to the influence of horizontal lines on a project. Vertical lines on an object are found to produce an analogous effect vertically.

Gothic cathedral builders used the vertical line, repeated again and again in buttresses, pinnacles, and spires to give great apparent height to a building and to make it a unified vertical mass of great beauty. The modern church spire, together with the long, vertical interior columns, similarly affects our present day church edifices.

This idea of repeating the vertical bounding lines of the primary mass by cutting the mass into vertical spaces is also useful in breaking up or destroying the monotony of large unbroken surfaces. Pilasters may cut the front of a building into interesting spaces; piers may break up the regularity of a long fence; legs and panels may, each [35] for the same purpose, cross a cabinet. While some of these may be structurally necessary and some not, they are all witnesses to the desire to produce beauty in design. As these examples are so numerous in the industrial arts, it is well to study in detail their proper adaptation to our needs.

Upon analyzing one vertical space division, it will be found to be a primary mass, vertical in character and governed by Rule 1a. Figure 25, Plate 12, illustrates one vertical division. The foot is an appendage to be considered in Chapter V.

Rule 3a. If the primary mass is divided into two vertical divisions, the divisions should be equal in area and similar in form. Exception may be made in case of structural requirements. By imagining two adjacent doors of equal size, the design effect of two vertical divisions may be made clear. Plate 11 illustrates a rectangle (A) divided in this manner, preliminary to the development of a problem. Figure 27, Plate 12, represents the type of object to which the exception to the rule may be applied. In the design of this desk, the structure practically prohibits two equal vertical divisions, necessitating an unequal division in the section occupied by the drawers.

In Plate 12, Figure 26, the designer had his vertical spacings dictated by service in the form of two doors. As service demands a tall vertical primary mass, it is but natural to design the doors to conform with the primary mass. This gives a monotonously long space for the glass panels and suggests structural weakness. To relieve this the designer applied Rule 2a and crossed the vertical panels by horizontal subdivisions, relieving the monotony and still retaining the unity of the primary mass.

In Figure 27 his problem was a variation of that presented in Figure 26. Structural limitations called for unequal divisions of the vertical space arrangement. The left portion of the desk becomes dominant as demanded by service. The drawer or brace is necessary in this design as it acts as a sort of link, binding the two vertical legs together. The omission of the drawer would destroy the unity of the mass.

As vertical space divisions are principally applicable to rectilinear or flat objects and moreover as it is in such forms only that they [37] have structural value, they are not commonly met in cylindrical pottery ware. Vertical divisions are, however, occasionally used in architectural tiles and other flat wall objects. As three divisions are much more commonly used in clay and cement, this material will now be left for later consideration in this chapter.

Vertical spacings in metal are quite similar to space divisions in wood. Wrought iron fences are, by reason of structural limitations composed of vertical and horizontal lines, varied by the introduction of piers and curved members. As they are typical of a certain branch of iron construction, two designs of the Anchor Post Iron Company have been introduced. Figure 32, Plate 14, represents two equal vertical divisions made so because of structural and aesthetic demands. The piers in this instance form a part of the general design of the entire gate and must be considered accordingly.

The vertical subdivision in Figure 32, Plate 14, has been repeated or echoed by the long vertical bars, alternating with the shorter ones and producing pleasing variety. The horizontal divisions are designed according to Rule 2b. In designing the newel lantern in Figure 34 the designer was required to form a vertical primary mass to conform with the similar mass of the post. This he determined to subdivide vertically in practically the same manner as the cabinet in Figure 26. Threatened with the same monotony he met the situation by subdividing the vertical sections into three horizontal divisions in accordance with Rule 2b. The structural supports, however, rising up in the center of this mass, destroy its unity. They would have carried out the lines of the structure of the newel post and continued the lines of the lantern better, if they had been attached to the corners rather than to the sides of the newel post.

Rule 3b. If the primary mass is divided into three vertical divisions, the center division should be the larger, with the remaining divisions of equal size. A large building with a wing on either side will give an idea of this form of spacing. The size of the main building holds the wings to it, thus preserving the unity of the structure, while equal divisions on either side give balance. Plate 11 (B) gives an example of a rectangle divided in this manner. This three-division motive is a very old one. In the middle ages painters and designers used [39] three divisions or a triptych, as it is called, in their altar decorations. A painting of the Virgin was usually placed in the center division with a saint in each of the remaining panels to the right and left. Designers and mural decorators have been using the triptych ever since that period.

The desk in Figure 28, Plate 12, is a good example of the three-vertical space rule. The drawer in the center forms the mid or dominant section and by its greater length holds the two smaller sections together. This design is better than Figure 27, which has a similar mass. The prominent vertical lines in Figure 27 counteract and destroy the effect of the long horizontal dominant lines of the table top, whereas in Figure 28, the vertical lines in the center of the design are so short that they do not interfere with the horizontal lines of the table top. Figure 28 supports the horizontal tendency of the primary mass while Figure 27 neutralizes or practically destroys its character.

Figure 30, Plate 13, represents an overmantle by the Rookwood Potteries. It is typical of a class of overmantles which may be developed in tiles or in cement, forming an agreeable contrast with the brick of a large fireplace. The three divisions or triptych should be proportionately related to the opening of the fireplace and to the enclosing mass of brick or wood work. We will consider Figure 29 to show how this may be carried out.

Figure 29 bears a strong resemblance to Figure 12, Plate 9, and is an elaboration of a simple three-division theme of spacing. The design seems to be complex until it is analyzed into two rules. The primary mass of the entire fireplace motive (including the surrounding panelling) has first been planned with strong and prominent horizontal lines. This was then divided vertically (A) to conform with Rule 3b, the three-division theme, giving the divisions for the bookcases and mantle. The horizontal divisions (B) were then constructed within the remaining space, affecting the distance from the picture moulding to the mantle and from the mantle to the floor line, in accordance with Rule 2a. That left the space of the width of the cement work (C) to be subdivided again by Rule 3b, while the top of the wainscoting panels re-echoed the previous horizontal divisions of Rule 2a. The fireplace opening merely carries out at D the same proportionate relation that dominates all vertical divisions, Rule 3b, while the wainscoting follows the general horizontal divisions of Rule 2a. By this method we have variety in spacing and unity through repetition of similar proportions.

[41] The cement bench, Figure 31, has a three-division arrangement to break up the monotony of the long rail, and at the same time to repeat the characteristics of a horizontal primary mass.

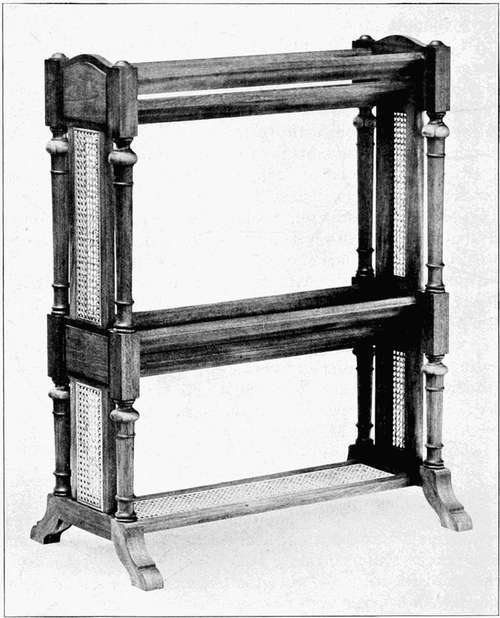

Figure 33, Plate 14, is a common example of three vertical divisions in metal suggested by the needs of service. Figures 35 and 36 are thin metal problems. The familiar pen tray is primarily a horizontal mass, so determined by its required service as a pen holder. The projecting handles form the outer divisions, and the spacing motive, Rule 3b, has been repeated in the raised projection, decorating the handles. The book rack in Figure 36 is an example of the manner in which a nearly square mass, so designed for structural reasons, may, by Rules 3b and 2a, be broken into a fairly pleasing arrangement of divisions.

Rule 3c. In elementary problems, if more than three vertical divisions are required, they should be so grouped as to analyze into Rules 3a and 3b, or be exactly similar. The eye becomes confused by a multitude of vertical divisions and it is much better designing to keep them within the number stated in this chapter. There are instances, however, when this is impossible. Under such conditions the following treatment should be adopted:

Unless, as stated, a large number of vertical divisions may be grouped into two or three vertical divisions it is better to make all of the divisions of the same size. This does not fatigue the eye as much as would the introduction of a number of complex spacings. This solution enables the amateur designer to deal with complex problems with an assurance of securing a degree of unity.

INSTRUCTION SHEET

Plate 15 is practically self-explanatory and shows the order in which the various divisions, so far considered, are to be introduced into the design together with the grouping of details within those divisions. Figure D introduces the additional element termed the appendage to be considered in Chapter V.

SUMMARY OF DESIGN STEPS

(a) Construction of the rectangle representing the vertical or horizontal character of the primary mass with desirable proportions. Select the most prominent surface for this rectangle, preferably the front elevation.

(b) Subdivide this rectangle into two or three structural sections, horizontal and vertical in character. Make two or three trial freehand sketches on cross section paper for varied proportions and select the most pleasing in accordance with rules.

(c) Translate the selected sketch into a scale or full size drawing and add additional views to complete the requirements of a working drawing. Add additional structural elements: legs, rails, etc.

(d) For shop purposes, enlarge a scale drawing to full size, dimension and otherwise prepare it for actual use. See Figure 102a, page 68, for character of this change.

(e) Construct the project.

SUGGESTED PROBLEMS

Design a fire screen with two horizontal and three vertical major subdivisions.

Design a bookcase 4 feet 2 inches high with three horizontal and two vertical major subdivisions.

SUMMARY OF RULES

Rule 3a. If the primary mass is divided into two vertical divisions, the divisions should be equal in area and similar in form.

Rule 3b. If the primary mass is divided into three vertical divisions, the center division should be the larger, with the remaining divisions of equal size.

Rule 3c. In elementary problems, if more than three vertical divisions are required, they should be so grouped as to analyze into Rules 3a and 3b, or be exactly similar.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. What is the nature and need of vertical space divisions?

2. State the rule governing the use of two vertical space divisions and give illustrations in wood, clay, and metal.

3. Give the rule relating to the use of three vertical space divisions and furnish illustrations in wood, clay, and metal.

4. What is the treatment of more than three vertical divisions? Why?

An appendage is a member added to the primary mass for utilitarian purposes. In the industrial arts, when an appendage is added merely for the purpose of decoration, it is as useless and functionless as the human appendix and, as a source of discord, should be removed.

An appendage in industrial arts may be, among other things, a plate rail, bracket, spout, cover, or handle, all of which are capable of service either for or with the primary mass. In architecture it may be a wing or ell added to the mass of the building. Simple as its design may seem, it is often so placed in relation to the main or primary mass that it does not seem to "fit" or to be in unity with that mass.

Rule 4a. The appendage should be designed in unity with, and proportionately related to, the vertical or horizontal character of the primary mass, but subordinated to it.

Rule 4b. The appendage should have the appearance of flowing smoothly and, if possible, tangentially from the primary mass.

Rule 4c. The appendage should, if possible, echo or repeat some lines similar in character and direction to those of the primary mass.

All of the foregoing rules are intended to promote the sense of unity between the primary mass and its appendages. If a mirror on a dresser looks top-heavy it is generally due to the fact that it has not been subordinated in size to the primary mass. Rule 4a. If the handle projects from the primary mass of an object similar to the handle on a pump, it has not been designed in accordance with Rules 4b and 4c. Again, if the appendage projects from a primary mass like a tall chimney from a long flat building, it has violated Rule 4a and has not been proportionately related to the character of the vertical or horizontal proportions of the primary mass.

It should be readily seen that if the primary mass has one dominant proportion while the appendage has another, there will be a [45] serious clash and the final result will be the neutralization of both motives, resulting in either an insipid and characterless design or a downright lack of unity.

The design of the small dressing table, Figure 37, Plate 16, with the mirror classing as an appendage, is an excellent illustration of Rule 4a. The main mass of the table is vertical in character and the mirror carries out or repeats the character of the primary mass by having a similar but subordinate vertical mass. In this instance it is so large that it has nearly the effect of a second primary mass.

As tangential junctions are difficult to arrange in wood construction and particularly in furniture, the break between the table top and the mirror has been softened by the introduction of a bracket or connecting link. The curves of the link cause the eye to move freely from the primary mass to the appendage and thus there is a sense of oneness or unity between the two masses.

The lantern in Figure 38 becomes an appendage and is subordinated to the large pedestal or support. The tangential junction has in this case been fully possible and the eye moves freely from the vertical lines of the base to the similar vertical mass of the lantern without noticeable break.

The service of the dressing table, Figure 39, with its three-division mirror makes the problem of adaptation of the appendage to the mass of the table, in accordance with the rules, much more difficult. Under the circumstances, about the best that can be done, at the same time keeping within the limitations of desired service, is to plan the mirrors in accordance with Rule 3b, with the dominant section in the center. To secure an approach to unity, each section of the mirror should echo the vertical proportion of the primary mass of the table.

The top of the writing stand, in Figure 40, is an example of a horizontal appendage which repeats the horizontal character of the front or typical face of the primary mass of the table. The small drawers and divisions again take up and repeat the horizontal motive of the table, while the entire appendage may be subdivided under Rule 3b, giving the dominance to the center portion. The short curves in the appendage all tend to lead the eye in a satisfactory and smooth transition from one mass to the other or from the table [47] top to the appendage. The proportions of the small drawers are similar to the proportions of the table drawers. Rule 4c. All of these points of similarity bring the masses into close unity or oneness of appearance.

The table legs, in Figure 41, are more difficult to adjust satisfactorily. The idea of the designer is, however, apparent. The legs leave the column of the table with a tangential curve and, sweeping out with a strong curve, repeat the horizontal line of the table top in the horizontal lines of their bottom surfaces.

Figure 41a, a modification of Figure 39, shows close unity between the three divisions of the mirror due to the pleasing curve of the center section with its tendency to bind the other sections to it. Again, the echoing of the spacings of the three drawers in the similar spacings of the three mirrors, makes the bond of unity still closer to the ideal arrangement. Rule 4c.

Figures 41b and 41c are, in a way, parallel to Figure 41. The eye moves freely from the feet (appendages) along the smooth and graceful curves to the tall shaft or column of the primary mass. The turned fillets, introduced at the junction of the appendage and the primary mass, in Figure 41c, have a tendency to check this smooth passage making the arrangement in Figure 41b preferable. The hardware for the costumers is well chosen and in sympathy with the vertical proportions of the design.

With the word "clay" all difficulties in the treatment of appendages vanish. It is by far the easiest medium for the adaptation of the appendage to the primary mass. Covers, handles, and spouts are a few of the more prominent parts falling under this classification.

The process of the designer is to create the primary rectangle, subdivide it into two horizontal subdivisions in accordance with Rule 2a, and proceed to add the desired number of appendages. The result may be suggested by the following illustrations. In Figure 43, Plate 17, the cover is a continuation of the curve of the top of the bowl, Rule 4a; the tops of the handles are continuations of the horizontal line in the top contour of the bowl, while the lower portions of the handles seem to spring or grow from the lower part of the bowl with a tangential curve.

Figure 44 is a horizontal primary mass with the horizontal subdivision in the upper section of that mass. The spout and handle spring naturally from the body and balance each other in proportion, while the cover handle rises smoothly from the primary mass. The horizontal character of the primary mass is consistently carried out in the appendages.

The handle, in Figure 45, leaving the body at a tangent, rises with a long straight curve to turn suddenly and join the pitcher in harmony with its top. The apparent abruptness of the junction is softened by the rounded corners typical of clay construction.

The Rookwood set, Figure 42, represents three similar primary masses. The proportionate ratios and the horizontal subdivisions are the same throughout. The handle for the teapot has been curved in the center to give variety to the handle. This variation is a difficult thing to manage without consequent loss of unity as by this variation Rule 4a is violated. One thing may be said in its favor. It brings the hand closer to the spout and thus supports the pouring weight. But the unusual in design is to be discouraged until sufficient skill in simple designing has been acquired.

In designing handle appendages for clay, they should be so placed that they readily control the weight of the material in the container and afford room for the fingers. Thus, it is better to have the larger portion of the handle opening at the top of the primary mass. The spout in all instances should continue sufficiently high to allow the container to be filled to its full capacity without danger of the contents running out of the spout. The glaze runs into rounded corners much more freely than into square ones, hence it is preferable to use rounded corners wherever possible.

It is the unexpected curve that is welcome in all designing, provided it supports the structure and conforms to established rules. After completing a design involving appendages it should be checked from three points of view; (1) service, (2) unity between the primary mass and the appendages, and (3) variety of curvature. On this last point it is needless to say that compass curves are not desirable except in rounding small corners or in using fillets. It is well known that compass curves are difficult to assimilate into pleasing tangential effects. They are inclined to be monotonous and regular with a [51] "made by the thousand" appearance to them. One should trust to freehand sweeps, drawn freely with a full arm movement when possible. All curves should spring naturally from the primary mass. Blackboard drawing is excellent practice for the muscles used in this type of designing. In a short time it will be found possible to produce the useful long, rather flat curve with its sudden turn (the curve of force) that will make the compass curve tame and commonplace by comparison.

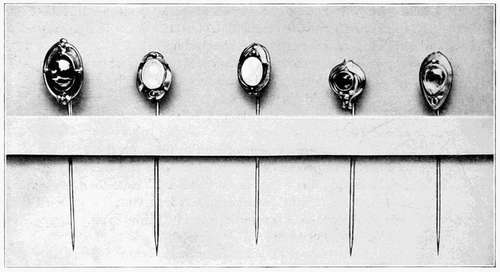

Figures 55, 56, and 57, Plate 18, show the close bond between the appearance of the appendage in clay, and the one in metal. While it is technically more difficult to adapt metal to the rules governing appendages than is the case with clay, the final results are, in most instances, equally pleasing to the eye.

In most of the figures showing examples in metal, the appendages have to be secured to the primary mass by screws, rivets, or solder, whereas in clay they may be moulded into the primary mass. This tends to secure a more unified appearance; but in metal, the junction of the handle and the primary mass is often made a decorative feature of the design and gives added interest and variety to the project.

The simple primary mass, Figure 58, has a horizontal space division in the lower portion of the mass. This point of variation of the contour has been used in the primary masses in Figures 55, 56, and 57, also as the starting point of that dominant appendage, the handle. Springing tangentially from the body, it rises in a straight line of extreme value in service, then with a slight turn it parallels and joins the top of the bowl, thus fulfilling the design functions of an appendage from both points of service and beauty. The spout and lid, Figure 55, may be likewise analyzed.

The points of tangency, in Figure 54, become a decorative feature of the design. The handles in the parts of the fire set, Figures 48 and 49, offer different problems. It is difficult to analyze the latter figures to determine the appendages as they are in such thorough unity with the handles and are practically subdivisions of the primary mass. But referring to the rule stating the fact that the appendages are subordinated to and attached to the primary mass, it may justly be stated that the shovel portion of the design may [53] legitimately be classed as an appendage. This will explain the need of a curve at the junction points and the feature of the decorative twists in Figure 49. Both designs may be analyzed into three horizontal divisions.

The andirons, Figures 50 to 53, illustrate interesting transitions in wrought iron from the primary mass to the appendage. The vertical shaft of wrought iron has been treated as a primary mass while the feet may be classed as appendages. In Figure 50 we have an example of a frankly square junction point. Figure 51 discloses a weld with rounded corners, forming a more pleasing junction than does the abrupt angle of Figure 50. This conforms to Rule 4b. The appendage legs echo or repeat the vertical lines of the primary mass and there is consequently a sense of unity between them.

In Figure 52 the appendage foot is curved, and the primary mass has a similar curve on the top of the vertical column to apply Rule 4c to repeat the curve. The small links at X indicate an attempt to make the junction point more pleasing to the eye, but the link is too large to accomplish the desired result successfully. In Figure 53 the links have been materially reduced in size and in the amount of curvature. In this example the eye goes unhampered from appendage to primary or back again, without perceptible interruption and the unity of the mass, seriously threatened in Figure 52, is restored in Figure 53.

In Figure 46 there is an example of a link becoming large enough to be classed as an appendage connecting two primary masses, e.g., the lantern and the wall. Under these conditions, one end of the appendage harmonizes with the lantern and the other end with the wall. Figure 47 shows a cast brass candlestick which is an excellent example, from the Studio, of tangential junction.

Clay may readily stand as the most adaptable material for appendages, with metal ranking second, and wood third. The grain of wood seems to interfere with the tangential junction of the appendage and primary mass. Appendages of wood are, however, quite necessary at times. Their use is merely a matter of lessening the contrast of conflicting lines in an addition of this nature.

The band and bracket saws are required in many instances to construct the connecting link between opposing masses of wood. Hand building or casting is the means used to construct the appendages in plastic materials. Appendages in cement are seen in the uprights for cement seats and are generally translated into the primary mass by means of mouldings or curves.

Forging or thin and raised metal construction affords many examples of the adaptability of material in constructing appendages. Rivets form decorative features at the junction points and should be placed with great care and relation to the decoration and the point of tangency.

INSTRUCTION SHEET FOR CLASS PRESENTATION

The typical views to be used in classroom work, with the ordinary range of problems, are shown on Plate 19. These typical views should be supplemented by dimensions, cross sections, and other views whenever necessary. Wood construction has been omitted from this sheet, but its development in design is quite similar to the steps indicated in the summary.

SUMMARY OF DESIGN STEPS

(a) Draw the primary rectangle.

(b) Subdivide the rectangle into two or three horizontal and, if necessary, vertical divisions.

(c) Estimate the dimensions of the appendage necessary to perform the desired service in the best manner.

(d) If the appendage is a handle, place it in such a position that it not only appears to but actually does support the weight of the primary mass.

(e) Complete the contour curves of the primary mass based upon the horizontal division which acts as a unit of measurement or a turning point.

(f) Join the appendages to the primary mass by means of tangential curves.

(g) Establish unity between the primary mass and the appendages by applying Rules 4a, 4b, and 4c.

(h) Dimension and otherwise prepare the drawing for shop use. See Plate 26.

SUGGESTED PROBLEMS

Design a sugar bowl, cream pitcher, and teapot. Consider them as different members of one set.

Design a sideboard 3 feet 3 inches high with plate rack, the design to contain two vertical and two horizontal divisions exclusive of the appendage.

SUMMARY OF RULES

Rule 4a. The appendage should be designed in unity with, and proportionately related to, the vertical or horizontal character of the primary mass, but subordinated to it.

[56] Rule 4b. The appendage should have the appearance of flowing smoothly and, if possible, tangentially from the primary mass.

Rule 4c. The appendage should, if possible, echo or repeat some lines similar in character and direction to those of the primary mass.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. State the nature and use of the appendage.

2. What is the relation of the size of the appendage to the size of the primary mass?

3. How should the appendage be attached to the primary mass?

4. How does Rule 4c help to secure unity between the appendage and the primary mass?

5. Are compass curves permissible in appendage design?

6. State influence of tools and materials upon appendage design.

With this chapter we introduce contour enrichment, the second major division of industrial arts design.

A critic of furniture designed by the average manual arts student has stated frankly that while it might have been honestly constructed it was, in the first place, too heavy for a woman to move about the house and, in the second place, it represented a decidedly uneconomical use of that valuable material, wood. That there is a basis in fact for this statement cannot be denied. Is it true, then, that furniture must of necessity be clumsy and heavy when it is sufficiently simplified in constructive processes for school work? We may say emphatically, "No!"

One may correct the proportions of an object and reduce the size of the materials in it to a minimum but still fail to secure the desirable elements of lightness and interest. The object may still look heavy and remain a box-like structure void of the grace synonymous with the best in design. It is, however, possible to correct the clumsy and heavy appearances by imparting to the design elements of grace and lightness. Two methods may be used, singly or together: (1) Enrichment of the Functional Outlines or Contours; (2) Surface Enrichment sometimes called Space Filling. These may be roughly classified respectively as three and two dimension enrichment.

The first, or outline enrichment, concerns itself with the structural lines. As all designing processes should start with the structure, it will be our policy to do so. The present chapter will deal only with enrichment of outlines of wood projects.

Rule 5a. Outline enrichment should be subordinated to and support the structure.

Rule 5b. Outline enrichment should add grace, lightness, and variety to the design.

It is the purpose of enrichment to add to the problem (1) grace; (2) lightness; (3) variety; (4) unity. If it is applied in a proper manner it should likewise add to the apparent structural strength. We should carefully guard the design, therefore, against (1) enrichment that has a tendency to obscure or destroy the structural lines; in other words, enrichment that is not subordinated to the structure, and (2) enrichment that adds nothing to the structure by its application; that is, one which does not increase either the apparent strength or the beauty of the object.

As an example of this first point, the turned candlestick with the candle supported by a stack of turned balls alternating with tauri or thin discs tends to obscure completely the sense of support. Again, the landscape gardener feels that he is violating a fundamental principle in design if by planting vines to grow around a building, he obscures the foundation, and the roof appears, consequently, to rest on and be supported by the stems and leaves of the vines. Thus it is seen that the eye registers a sense of structural weakness when the main supports of an object disappear and are no longer to be traced under the enrichment.

Under the second point falls the indiscriminate placing of unrelated objects in the contour enrichment. Naturalistic objects similar to the claw foot and the human head, for example, should give way to natural curves that add to the appearance of total strength. Where are we to find these curves suited to our purpose?

Up to this point emphasis has been placed upon straight and curved lines immediately connected with pure service. For grace and lightness it is necessary to depart at times from the rigidity of straight lines. To understand the character of this departure let us consider a simple bracket as a support for a shelf.

This bracket acts as a link, connecting a vertical wall or leg with a horizontal member or shelf. A bracket shaped like a 45-degree triangle, Figure 10, page 24, gives one the sense of clumsiness. If the feeling of grace is to be imparted the eye must move smoothly along the outline of the bracket, giving one a sensation of aesthetic pleasure. A curved line will produce this effect more completely than will a straight line. One must likewise get the feeling that the curve of the bracket is designed to support the shelf.

Turning to Figure 70, Plate 20, we find that whenever nature desires to support a weight she is inclined to use a peculiar curve seen at F. Possibly through continued observation the eye has associated this curve with strength or supporting power. Figure 71 has detailed this curve. It is found to consist of a long, rather flat portion with a quick and sudden turn at its end. The curve is known to designers as the Curve of Force and is most valuable in all forms of enrichment. Designers even in early ages used it in some form as will be noted from the fragment of Greek sculpture in Figure 72. Its beauty rests in its variety. A circle has little interest due to its rather monotonous curvature. The eye desires variety and the curve of force administers to this need and gives a sense of satisfaction. As designers on wood, how are we to utilize this curve for purposes of outline enrichment?

For approximate similarity of curvature an ellipse constructed as shown in Figure 73 will be found convenient. By drawing several ellipses of varying sizes upon sheets of tin or zinc, a series of templates of utmost practical value may be formed and used as was done in securing the curves of force in Figures 74 and 75. If the rail or shelf is longer than the post, measured downward from the rail to the floor or to the next shelf, the ellipse should be used with its major axis placed in a horizontal position, Figure 75. If, on the contrary, the post is longer than the shelf the ellipse should have its major axis in a vertical position, Figure 74. Figures 76 and 77 show other instances of the use of the approximate curve of force. Many similar practical applications will occur to the designer.

We have classed the bracket as a link connecting a vertical and horizontal structure. Mouldings may likewise be considered as links connecting similar horizontal or vertical surfaces by bands of graded forms. Inasmuch as they effect the outline they are considered in this chapter. As the mouldings are to assist the eye to make the jump from one surface to another by easy steps, the position from which the mouldings are to be seen determines to some extent their design.

Figure 78 shows the relation of the spectator to three types of mouldings at A, B, and C. The top or crown (A) is to be seen from [63] below. On a large project the angle of the mouldings with the body of the object should be approximately 45 degrees. The intermediate moulding (B) is lighter than the crown and forms a transitional link that may be seen from either above or below. The lower or base moulding (C) is the widest member of the group as demanded by our sense of stability. It is seen from above. Both for sanitary and structural reasons it projects but slightly from the base. With this grouping in mind it is needless to say that a faulty moulding is one, some portion of which, hidden by intervening moulding, cannot be seen by the spectator.

Architectural design and history have formulated a series of curves, geometric in character, that are regarded as standards in the Industrial Arts. Some of the more prominent curves with their constructions are shown in Figure 79. The horizontal divisions are analyzed in accordance with Rules 2a and 2b. It is noticed that the Scotia possesses a curve having the shape of the curve of force, while the two Cymas are saved from monotonous division by means of their reversed curves, illustrating the contrast of direction. The curves of Figure 80 are excellent lines for freehand practice in designing mouldings and will develop the principle of continuity of curvature or the smooth transition of one curve into the next.

To keep this continuity from the monotony of a Marcel Wave it is customary to break continuous curves by a fillet such as a straight line as shown at D, Figures 81, 82, and 83. When the desired outside diameter has been reached, contrast of direction is necessary and pleasing as a return, Figure 82. A glance at the curves so far considered will quickly determine whether they are fitted for the crown, intermediate or base mouldings. A curve should join a straight line with either a tangential or right angle junction, which makes for positiveness in contour expression.

Application of these curves to outline enrichment for wood turning projects is to be governed by a strict adherence to Rules 2a or 2b, otherwise confusion and lack of unity will result. Figure 83 shows a major grouping under Rule 2b with the subdivisions and minor curves arranged under Rules 2a and 2b. Figure 84 shows a disregard for rules and the result is an undesirable monotony of contour. If smooth and even continuity of curvature is given [65] considerable thought, together with that for systematic grouping and variety, a pleasing result from wood turning (a much abused but pleasing form of outline enrichment) may be secured. Figures 85 and 86 are illustrations from the industrial field with moulding curves grouped, following and supporting the structural lines of the object. The columns in Figure 86 might, however, be advantageously reversed.

Courtesy of Berkey and Gay

Figure 86.—Modern Book Trough

Large objects designed to be seen from a distance require larger space divisions for their mouldings than do small objects seen from a nearer point. Material affects the curve somewhat. Smaller mouldings are more suited to the expensive woods like mahogany while larger curves may be used in pine or oak.

We now have at our command a number of interesting and serviceable curves suited to the material. Plate 22 is a sheet of applications. Figures 87 to 94 deal with the book-rack end and in this, as in the initial chapter, architecture is referred to as the source for many laws of industrial design. It has seemed wise to illustrate some of these important parallels as follows:

We will assume the type of joint construction of the book-rack end as settled and the question of enrichment to be under consideration.