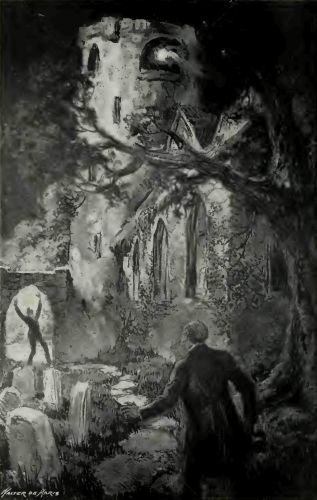

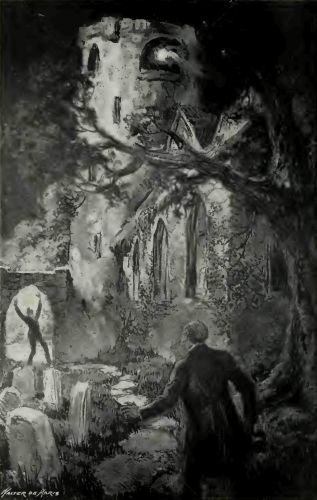

"Mr. Narkom saw Cleek run to the tower's foot ... and then, almost immediately, he saw him throw up both hands and stagger backward."

"Mr. Narkom saw Cleek run to the tower's foot ... and then, almost immediately, he saw him throw up both hands and stagger backward."

"Mr. Narkom saw Cleek run to the tower's foot ... and then, almost immediately, he saw him throw up both hands and stagger backward."

"Mr. Narkom saw Cleek run to the tower's foot ... and then, almost immediately, he saw him throw up both hands and stagger backward."

There are days, even in the capricious climate of London, when the whole world seems at peace; when the blue of the summer sky, the fragrance of some distant flower brought in by a passing breeze, and the contented chirp of the birds, all unite to evoke a spirit of thankfulness for the very gift of life itself.

This was the spirit of Mr. Maverick Narkom, Superintendent of Scotland Yard, on this particular day in July. Even the very criminals had apparently betaken themselves to other haunts and distant climes, and the Yard, therefore, may be said to have been surprisingly slack. Up in his own private room, seated in front of his desk—both desk and room reduced to a state of order and tidiness uncanny to behold—sat the Superintendent, if the truth must be told, oblivious to all the world; a purple silk handkerchief draped itself gracefully over his head and rose softly up and down with the rise and fall of[Pg 4] his breath. This was his last day at the Yard, for to-morrow would see him well on the road to Margate for a blessed two weeks' holiday with Mrs. Narkom and the children, not to mention guests who were nearly as precious to him, namely Ailsa Lorne and Hamilton Cleek.

His famous ally had himself been absent for more than two months, but was returning this very day—day, in fact, might be expected to arrive now at any minute, so it was little wonder that peace reigned supreme in the worthy Superintendent's heart, and induced his gentle slumbers even in the sacred precincts of what has been termed the Hub of London.

But outside, in the blue azure of the sky above, a tiny cloud, no bigger than that of the proverbial man's hand, had gathered, and as if it were a reflection of the storm-clouds of crime hovering round, there came the sharp ting-ting of the telephone bell at his elbow. For a minute, thus suddenly aroused, Mr. Narkom stared blankly at the disturber of his peace. A swift glance at the indicator told him it was a summons from the Chief Commissioner, and Mr. Narkom betook himself to the interview.

It lasted only fifteen minutes as registered by the clock ticking gently on the mantelshelf, but its deadly effect was that of fifteen years on Mr. Narkom, and when he once more entered his own official sanctum, he sank down into the chair with a groan. For he had heard the first details of that mystery of the[Pg 5] haunted village of Valehampton, which later on was to rouse a whole county, and bring to Hamilton Cleek one of the chief problems of his career. That the strangeness of the case was apparent on the face of it could be gathered from Mr. Narkom's muttered remarks.

"Curses!" he growled. "Suicides! Murders! Ghosts! Prophecies! It's the work of the devil himself." He consulted his notes again, but though copious enough, it was clear they afforded no further light. He pulled out his watch and heaved a sigh of relief. "Only half-past nine now," he ejaculated, "and if only Cleek arrived safely by the 8:40, I think he said, at Charing Cross, there's a chance of seeing light. I don't know where he's been, the amazing beggar, but he's never been wanted so badly here in his life. Thank goodness he's back again."

He reached out a hand for that friendly instrument the telephone receiver; but his complacent gratitude had evidently tried the patience of the Fates, for ere his fingers closed round the familiar black handle, the door of his room was thrown violently open, and without ceremony or even apology a slim figure fairly hurled itself before the gaze of the astonished Superintendent.

It was Dollops, worshipper of Cleek and his ever-faithful assistant. His face was the colour of a Manila paper bag, and his eyes bulged out of his[Pg 6] head as they took in the fact that Mr. Narkom was alone.

"Lor' lumme!" he cried, relapsing into broad cockney, as he invariably did when excited. "Don't go for to say he ain't 'ere, neither," he blurted out, his eyes seeking those of Mr. Narkom with a very agony of impatience.

For both of them there could be but one "he," and Mr. Narkom's face became nearly the same colour as the lad's as he realized that his famous ally was not at hand.

"Didn't he arrive at Charing Cross by the 8:40?" he cried.

Dollops shook his head.

"No, bless 'im, that's just what he didn't do, Mr. Narkom. Me and Miss Lorne waited for 'im, me wivout so much as a bite to keep my insides from sticking together, and them blooming Apaches—beggin' your pardon, Mr. Narkom, but they are blooming, too—merry and bright they was, I tell you, buzzing round that station like bluebottles round a piece of meat. That's wot made me come 'ere, thinkin' he'd twigged 'em as usual and come another way. But if 'e ain't 'ere, 'e ain't, and I'll get back to Portman Square."

With a dejected lurch of the shoulders, he turned, leaving Mr. Narkom to make his own preparations.

Soon deep in the business of issuing orders to his underlings, despatching telegrams—one, of course,[Pg 7] to Mrs. Narkom herself to prepare her for the disappointment of a postponed holiday—and in writing and expanding the notes of this last case just entrusted to him by his chief, Mr. Narkom for the first time in his life since he had known and learned to love his famous ally, Hamilton Cleek, once known as the Man of Forty Faces by reason of his peculiar birth-gift, his ability to change instantaneously his whole appearance by an extraordinary distortion of his facial muscles, and also as the Vanishing Cracksman, for his capacity of extricating himself from perilous positions, and now as Cleek of Scotland Yard—for the first time, we say, Mr. Narkom forgot to be anxious at his evident non-arrival.

The sound of hurried footsteps in the corridor outside struck upon his ear and he wheeled suddenly in his chair. But if he had expected to see Cleek, he was doomed to disappointment. There came a knock, the door opened and closed, and a deprecatory cough came from Inspector Hammond, white-faced and anxious, his lips set in a grim line of tense anxiety.

"Hammond—why, what is wrong, man? Speak up," cried the Superintendent. "Come, out with it."

"It's 'im, sir," said Hammond. "A kid of a paper-boy just pushed this 'ere paper into my 'and as I was leaving my beat and 'ops it before I could as much as breathe Jack Robinson."

His hand shaking, he extended to the obviously[Pg 8] irritated Mr. Narkom a scrap of dirty paper, and as the Superintendent gave a glance at the few words scrawled on it, his own ruddy face was drained of every vestige of colour, and it looked not unlike that of Dollops but a brief half hour previous.

The scribbled words were barely half a dozen in number but in their import they told of more dire disaster to him than could any voluminous cabinet epistle.

Irregularly penned as by one in imminent peril, the message danced before his blurred eyes.

"Come, God's sake, 1st barge, Limehouse, Dock 3.—Cleek."

"What does it mean, sir?" asked Hammond, anxiously, as Mr. Narkom sucked in his breath and stood staring rigidly.

"Means," he gasped, "that they've got him, the devils. Dollops was right. Apaches! God, but he's gone by now perhaps. Cleek, my pal—my——"

He wheeled on the now frightened Inspector. "Quick, man—the car. You follow, with Petrie and whoever else is off duty."

Hammond needed no second telling. He almost fled from the room, and the dread news preceding him, Lennard was on the spot and waiting as impatiently as the Superintendent himself.

"Limehouse Docks, Lennard—and streak it. Mr. Cleek is in danger——"

"I know, sir. Hop in, and Lord help the man or[Pg 9] vehicle in my way!" was the fervent reply as he cranked up and took his seat.

"Streak it" he did, and not a policeman on duty, after a brief glance at his grim face and that of the Superintendent within, did more than hold up every cart, cab, tram, or 'bus that was likely to impede his way. Obviously the Yard, as vested in the sacred person of Superintendent Narkom and his prime minister Lennard, was "on active duty" and like a fire engine in speed and purpose, the Yard limousine rocked and swayed its way through grimy lanes and malodorous byways till it reached the squalid region known as Limehouse Docks. Here Lennard could go no farther, and ere the car had pulled up, quivering, the portly form of the Superintendent had thrown itself out, and was peering into the sunlit distances.

"Wait here, Lennard, and when the others come along bring them to Dock 3 and look out for Barge No. 1, if we are not here first."

"Righto, sir," said Lennard.

But already Mr. Narkom was out of sight, all other duties forgotten.

Swiftly he turned a sharp corner, nearly falling over a sailor leaning against the wall smoking a cigarette. At the first whiff, Mr. Narkom glanced up swiftly. It did not take his trained sense long to recognize that it was a French cigarette—hence Apache—and that Cleek must be here, in need of him!

"La, la, but you are queek," the man muttered. "It is ze brave Super-in-tend-ent and he come for his gr-great frien' Cleek—is it not so, my frien'?"

"Yes, yes—you know! He is here?" gasped Mr. Narkom, barely, if at all, stopping to think of any possible peril to himself. "You shall be finely rewarded for this, my good man," he said, warmly. "Lead on——"

"But yes," was the reply, "a brave reward. Come!" He turned silently and swiftly, beckoning to the Superintendent to follow.

Nothing loath and unsuspecting, Mr. Narkom turned and followed the sailor till they reached one of the docks—and a barge.

"This is dock 3," he said, as he noticed the number.

"Quite right," said his guide. "Get in, queek—ze boat—ze others, zay weel return and it weel be too late."

That was sufficient for Mr. Narkom. Obviously, his friend was in danger; equally obvious was it that this guide had brought him as a reinforcement against returning Apaches.

"Get in" he did, and it was not until he had stumbled down a dark companionway into the grimy cabin and heard the door click swiftly behind him that he realized he was trapped—deceived by a trick as simple as it had been effective. The sweat stood out on the Superintendent's forehead, rolling[Pg 11] down in great beads, while his hands grew cold and clammy.

"Cleek!" he cried, hoping even now that his ally were with him to help and be helped! But a light laugh—half snarl, half sneer—caused him to turn. His guide stood regarding him with mocking amusement.

"Bravo! my frien'—so easy it was! Caught like the great big turkey-gobbler. Oh, non, non—but not so queek, my frien'——"

For Mr. Narkom had flung himself forward in a vain effort to escape. A sharp whistle and a door hitherto unseen in the darkness of the cabin behind him was flung open. Mr. Narkom was seized from behind, flung down some three minutes later, and trussed up, panting and helpless, tears of rage and mortification in his eyes.

Soon, as it grew darker and darker, betokening the fall of the summer night, he felt the movement of the boat beneath him, and even while Lennard and a posse of his own men were interviewing the officials and overhauling Dock 1, the boat with its valuable burden was drifting out to meet a larger vessel, waiting well up the river's mouth, bearing away one of the only two men who could solve one of the greatest mysteries the Law had ever been faced with.

It was just dusk when the police officials were obliged to give up their quest for the Superintendent and Hammond returned to Scotland Yard to make his report to the Chief Commissioner. Dejected of mien and heavy of heart he stopped mechanically at the door of the Superintendent's room. He would have given worlds if he had never been the unconscious instrument of his superior's disaster. The door stood slightly ajar and he halted with the intention of closing it.

The electric light had been switched on and he stood in the doorway. A figure sat at the familiar desk and as the Inspector gave one brief glance, a cry of half pain, half fear, burst from his shaking lips.

"Mr. Cleek—you, sir! But——"

Cleek—for he it was—switched round in his chair, exclaiming at sight of the man's face, "Why, man! What's wrong?"

"Mr. Narkom, sir—they've got him. He's gone!"

"Got him—who've got him? He's not dead?"

Hammond shivered at that; then hoarsely and somewhat incoherently got out the tale of the afternoon.[Pg 13] And as Cleek realized the trap the Superintendent had bravely entered to save him, his friend and associate, from danger, he collapsed into the chair, his face hidden in the palm of his hand.

"God! A friend indeed! They think to hurt me through him," he muttered. "They'll never dare to injure him, surely! God, if only I hadn't lost that train—only by a minute, too! But I'll get him, I swear it. The rats shall pay for this——"

He leapt to his feet, his eyes narrowed down to slits, his lips set in a straight line, as he mentally reviewed once more the facts of Hammond's story.

"Leave me alone, Hammond. You can do nothing more. Keep a lookout at the docks. Tell Dollops I'm all right, and to lie low himself—or he'll be the next."

Hammond saluted and left the room, as Cleek turned to the telephone. A quarter of an hour later, out of the sacred precincts of the Yard itself, slouched one of the most villainous-looking Apaches that Soho or Montmartre itself ever could have seen. It was Cleek the Vanishing Cracksman, Cleek the Man of Forty Faces—the King Rat himself on the warpath. Had Marise of the Twisted Arm, Gustave Merode, or even Margot herself, the Queen of the Apaches, seen him, they would have feared and trembled.

Meanwhile, the barge had transferred its precious if bulky burden to one of the numerous produce boats going up the river and it was well on its way to Havre[Pg 14] before police launches or port officials were made aware of the loss.

But it was not until midnight had struck that the cramped, aching body of the Superintendent was hustled out of the boat at a little landing place outside the port itself, and smuggled hastily down into cellars of the Coq d'Or. Officials were too used to drunken sailors being helped in and out of this none too savoury tavern to note one more helpless, stumbling figure, held up between comrades, and a brief second found Mr. Narkom in the midst of an uproarious, shouting crew of Apaches, headed by no less than Margot herself, disguised as a Breton fishwife. She had escaped the eagle eye of her born foes, the French gendarmes, and here reigned supreme, surrounded by her compères in crime and those subject to her sway.

Her shrill cries of delight resounded to the roof as her eyes fell upon the gagged and bound figure of Mr. Narkom.

"Brava, brave Jules; so you succeeded! La! La! but we 'ave the rat himself now. This is the toasted cheese, and Cleek will come after his friend very soon—if we send for him. Eh, mes amis? A splendid plan, and meanwhile the good Duke is being hurt, eh! But it is good!"

Jeering and laughing, she thrust her face close to the drawn one of the Superintendent.

"But not so clever, eh, my friend? We cannot[Pg 15] afford to have you and Cleek, the rat!"—she spat the words out—"in England. We want a rest."

"Into the cellar—hark, what's that? All right, an aeroplane—that's all right. Into the cellar with him, lads. All we have to do now is to wait for the rat to come to the trap!"

To the accompaniment of another laugh, Mr. Narkom was pulled down into the vaults below, where, dazed with hunger, pain, and anxiety lest Cleek should indeed be led into fresh danger, he sweated an hour away.

Upstairs all was renewed merriment, and in the midst of it the door opened and a familiar figure slouched in—evil of face, disfigured with scars and bruises. As a shout arose at his appearance, there was no question as to his identity. "Merode. Nom de dieu, Gustave!" cried Margot. "But a pretty picture you cut!"

"Sacré nom!" he growled through his clenched teeth. "So would you, if you had been fighting for your life! The pigs of police are after me. Give me a drink and take me down through the cellar. The boat goes back to-night, doesn't it?"

"It does," said Margot. "Here's your drink—and drink to Jules there for he caught the turkey gobbler. Cleek the Rat's man—Narkom!"

"Nonsense—impossible!" cried Merode with an oath.

"But not so, my friend, you shall see him," cried half a dozen voices.

"See him? I'll mark him for life, the devil. Someone go for the vitriol—here!"

With dirty, scratched, and bloodstained hands, Merode threw a coin to one of the Apaches who vanished in the blue fumes of smoke and wine, while Merode slouched deeper into the shadows as there came the sound of a gendarme's clattering sword on the cobbles outside.

"Mon dieu, Margot, I mustn't be caught."

Margot gave orders swiftly. "Down with him, Jeannette, into the vaults, while I hold the fort."

Jeannette clutched Merode's arm. "Come, mon ami, through here! You know the way!"

Stumbling, cursing, praying all in one breath, Merode followed down the rickety wooden ladder, down, it seemed, into the very bowels of the earth.

Thrusting open another door, Jeannette grumblingly lighted a torch stuck in the woodwork, and as Merode's eyes fell upon the figure of Mr. Narkom an oath of triumph burst from his lips.

"Dieu, but Margot spoke the truth. It's the pig himself. I've half a mind to take him with me and make him dance with a hot iron or two! Better than vitriol——" He gave vent to a hoarse, chuckling laugh, at the sound of which the Superintendent shivered, even though the confined space was close enough on the hot summer's night.

"Margot will never stand that," said Jeannette. "She means to keep him here till Cleek the Rat comes——"

"Margot! Nom du pipe! If she is Queen, I am King. Leave him to me and give me the key of the door."

Jeannette wheeled suddenly on him.

"What key—what door?" she asked. Then without waiting for an answer she snatched the torch from the wall and thrust it in Merode's face.

He drew back from her piercing gaze.

"Hola!" she cried in triumph. "I was right—it is not Merode!" For Merode knew of the trap-door. And as the man followed her glance toward it he realized his mistake.

"And you, who are you?" she cried.

As the man shrank back she advanced, and with a swift gesture plucked at the matted hair. It came away in her hand, and her own cry of triumph as it revealed the smooth head beneath drowned the Superintendent's cry of "Cleek!" even as he realized the double peril of himself and the man whose friendship was dearer to him even than life itself.

"Aha, I know you now," cried Jeannette. "The great Cleek himself! And it is I who have got you—moi—whom she laughed at."

"And will again, ma petite," said Cleek, for he indeed it was. "Jeannette, be merciful, as you hope for mercy. Let me get my friend here through the[Pg 18] door into the boat and you shall deliver me up to Margot. I will come back—I swear it—if you set him free."

"Free to bring the gendarmes on us—pas si bête. No, my friend," laughed the girl.

"He will not do that, I swear it. Did Cleek the Cracksman ever break his oath?"

"No, but Cleek of what do you call your quarters—eh—ah—Scot-land Yard—eh—yes, he might!" said the girl.

Swiftly, in a torrent of French patois that Narkom could not follow, Cleek pleaded, disregarding the Superintendent's own pleas to exchange his life for that of Cleek himself.

Minutes passed and the girl remained obdurate. Suddenly she looked up.

"They say you have a white-and-gold lady to be your woman over on the other side—is it not so?"

Cleek shivered and shut his eyes in a veritable agony of spirit at this reference to Ailsa Lorne—his adored Ailsa who awaited him in the rose-clad riverside home, and who within a few brief days was to have been his wife.

A low, sibilant laugh burst from Jeannette's painted lips.

"Eh, but she would not like to know of this little meeting, my friend? She would scorn the poor Jeannette, eh? But it is Jeannette who holds you like that!" She snapped her finger and thumb in[Pg 19] triumph, and as the bursts of merriment above them seemed to roll nearer, Cleek grew very, very still. This was indeed the end, and though he would die for the sake of his friend, the blow would be none the less bitter.

Jeannette stood silent, too, looking at him. One, two, perhaps three minutes passed before she turned again.

"Well, mon ami, I don't know that I owe anything to Margot up there. What happens to me if I let you go? How do you pay me—eh?"

"Jeannette, you will? You have only to tell me what to do in return."

Cleek's voice trembled despite himself at this shadow of renewed hope, and Jeannette flushed in the dark.

"Bah, but I am the fool she calls me," she muttered, "But death comes soon enough. Pay me——" She came close to him, thrusting her face close to his. "No lover have I. I am old and plain; you are Cleek, once the lover of Margot the Queen. Kiss me! Nay, as you value your life and that of your friend there, kiss me as you would your woman over there—that is the price you shall pay!"

For one brief second Cleek's soul revolted. The thought of offering his lips—which he held sacred to the one fair woman who had led him up from depths such as these to her own pure level—sickened him. He would sooner yield life itself. Yet Narkom's[Pg 20] life depended on his own, and with a secret prayer for forgiveness he bent over, took the thin, shaking figure literally into his arms, and kissed the painted lips, not once, but thrice. "God bless you, Jeannette!" he murmured. "He alone can reward you."

With a little moan of pain Jeannette clung to him as if indeed he were the lover she craved; then, slipping from his arms, she turned, sped across the room, and tugged at a small, half-hidden trap-door.

"Quick," she panted. "Slash his ropes and go—before I repent! I'll tell them you've gone!"

Without another look or sound she disappeared up the staircase, leaving Cleek to make good the escape of them both, in his heart a prayer of gratitude, and a resolution to save Jeannette from this den of crime if he but lived to escape into safety.

Hardly daring to breathe, he and Narkom stumbled down another foul-laden ladder and into a noisome passage, which eventually brought them onto the little landing stage.

"I have the 'plane here," said Cleek, with a little happy laugh. "Be brave, my friend, but a few more minutes."

He vanished in the darkness, and though it seemed ages to the aching Superintendent, it was barely three minutes before the shadowy, whirring body of a War Office hydroplane hovered over him. Not more than five minutes later they were once more on the way to safety and to London, there to unravel the[Pg 21] riddle which had been propounded to the Superintendent by his chief but a few hours before.

"What's that, my friend—how did I find you?" said Cleek, later, when Mr. Narkom had got through a meal which would have done justice to Dollops himself.

"Well, I 'phoned for the use of one of our sea-planes, and scouted over every likely boat and barge in the Channel. When I saw one pass by Havre and stop just beyond, I remembered the old Coq d'Or and determined to risk it. And now, my friend, all you have to do is to rest. What's that? A case? Not to-night, Mr. Narkom, nor this morning. We both want rest and a quiet hour to offer up thanks to le bon dieu and Jeannette for our escape."

And that is why the case of the Mysterious Light, the riddle which was terrifying a whole village, was given no thought until many hours later. It had been a time too fraught with danger to be thought of lightly, and both men realized perhaps even more clearly the bond of friendship which had prompted both to walk into the very shadow of death in each other's service.

It was more than twenty-four hours later, and Superintendent Narkom, fully recovered from the effects of the awful night in the cellar of the Apaches at the Coq d'Or, was now in fine feather. Anything that had to do with what certain of his men were wont to allude to as "the hupper clarses" possessed an especial interest for him, and to-day's affair was flying high in the social scale indeed.

"A duke, I think you said?"

The inquiry came from beside him, from Cleek, as they both sat in the Superintendent's limousine, in which they were skimming onward in the direction of the Carlton, where they were due at half-past two.

"A duke—yes," agreed Mr. Narkom.

"But there are so many. And you whisked me off in such hot haste that there was no time to inquire which. Now, however, if you don't mind satisfying a natural curiosity——"

"The Duke of Essex. He came up to town this morning and called me to a private interview at his[Pg 23] hotel. It was a corroboration of what he told the Chief the other day."

"Ah!" said Cleek, with something like a twinkle in his eye. "That will be a pleasant little bit of news to tell Mrs. Narkom over the dinner table to-night. The Duke of Essex, eh? Well, well! That is the illustrious personage, is it not, who is famous for having a castle whose underground dungeons have been converted into a vast banqueting hall, and who is said to possess a service of gold plate which is the equal, if not the superior, of that which adorns the royal table on State occasions? That's the Johnnie, isn't it?"

"Yes, that's the—— My dear Cleek, you are hardly respectful, are you?"

"No, I am not. But you see, there must be something of the—er—well, fashionably democratic strain in my blood, and I'm never quite so overcome by the importance of dukes as a policeman ought to be. But we will stick to our—duke, if you please. Will his call upon us have something to do with guarding that gold plate and the very remarkable array of wedding presents which is sure to be an accompaniment to the marriage of his only child, Lady Adela Fulgarney?"

"Nothing whatsoever. It is an affair of a totally different kind."

"H'm! That is both disappointing and gratifying, Mr. Narkom. Disappointing, because I see by the[Pg 24] papers that Lady Adela's wedding is set for Thursday, the day after to-morrow; and gratifying, because to tell you the truth, I shouldn't much care to play the role of plain clothes man and special guard over the wedding gifts of even so important a lady as a duke's daughter."

"As if I would have brought the case to you had it been anything of the sort!" came reproachfully from Mr. Narkom.

"I think my only reason for imagining that the duke's call would be something in connection with Lady Adela's approaching marriage lay in the fact that a good many of the guests have, according to the newspapers, already arrived in Valehampton and either become domiciled at Essex Castle or at some of the neighbouring estates. At such a period one would naturally expect the duke to feel an interest in nothing but the forthcoming event—or, at least, not sufficient interest in anything else to cause him to leave his guests and make a flying trip up to London within forty-eight hours of the ceremony. It must be something of very serious importance, I take it, Mr. Narkom, to impel him to make this sudden visit to town and this urgent appeal to the Yard at such a time as this."

"It is. Wait until you hear the full details, old chap. I've had only a mere outline of them, but even that was sufficient to make me sit up. It's the devil's own business. And if Old Nick himself isn't at the[Pg 25] bottom of it I'm blest if I can imagine who in the world can be. You've tackled about all sorts in your day, but I don't think you ever went spook hunting before."

"Went what!"

"Spook hunting, ghost tracking, spirit laying—that sort of thing. That blessed village of Valehampton is haunted. The country folk are leaving it by the dozen. Half the duke's tenants have flown the place already, and the other half are getting ready to follow suit. That's what he's come up here for, that's what he wants you to do: Lay the ghost that's making life in the place a nightmare and driving people almost insane with fright."

"Tommyrot!"

"No, it isn't, Cleek—it's facts. The place seems under a curse on account of some infernal dead man who was buried there. The duke will give you the particulars—I can't—and the beggar's making life a burden to the village folk. Somebody or other said that a curse would follow wherever that dead Johnnie's body rested, and it has, too. One of the duke's tenants let it be buried from his house, and since that time nobody can live in the blessed place. And as for the church bells—lord! They make a perfect pandemonium of the neighbourhood at night—ring, bang, slam, without rhyme or reason, until people are silly with terror over the peal of them."

"Who rings them?"

"Nobody—that's the devil of it. The duke thought it was the work of somebody who was doing the thing for a lark, and he and the vicar had all the ropes removed. It didn't make any difference. The bells rang just the same the next night, and they've rung pretty nearly every night since. But that's not the worst of it. People have begun to be spirited away—out of their own houses, in the dead of night, without a blessed sign of where or how they went, and not a trace of them since. Last night, as if to cap the climax—— Hello! here we are at the Carlton at last. Jump out, old chap. We'll soon be with the duke now, and he will tell you."

The limousine had come to a halt. Mr. Narkom, opening the door, got out, dapper and sleek as always—doing the gentlemanly part of the Yard's business in a gentlemanly way—and Cleek, silk-hatted and morning-coated, the very antithesis of the professional detective, followed him, crossing the pavement and entering the hotel with an easy grace and repose of manner.

It was at once the envy and despair of his associates, that "way of carrying himself," as they expressed it, "like as if the earth wasn't none too good for him to walk upon, and he was sort of expecting a red carpet." And it was a curious fact that men of all classes on coming into contact with him were conscious of an indefinable something about the man which commanded rather than asked for respect.

And yet the man seemed, as a general thing, inclined to efface himself when in public. He did so now. Keeping in the background, he neither spoke nor asserted himself in any way; simply stood there and waited passively while Mr. Narkom sent up a card to the duke, and was wholly unperturbed when, a few minutes later, the messenger returned and stated that "His Grace would be pleased to see the gentlemen at once if they would kindly go up."

They went up forthwith, and were shown without delay into the presence of the Duke of Essex.

"Your fame is world-wide, Mr. Cleek, and I hold myself most fortunate in being able to have a man so ably equipped for taking up this amazing case," began the duke as Narkom introduced his famous ally. "I wish to enlist your services in ferreting out a very remarkable affair—in fact, one of the most unbelievable mysteries which even the fictionists could possibly evolve."

"Mr. Narkom has been giving me a hint of the case," said Cleek, as he seated himself upon the chair which the duke indicated. "It is about the reputed 'haunting' of the village where your country seat is located, I believe? I am told that you desire me to discover the mysterious agency which causes the church bells to ring without ropes or hands and is supposed to be accountable for the mysterious disappearance of certain persons."

"That's it precisely. I do not wonder at your smiling, Mr. Cleek. At first the affair appears so utterly absurd that it is difficult to imagine anybody with an ounce of brains regarding it seriously. Let me tell you the facts, however, and you will, I am sure, change your views upon that point as completely as I have been compelled to change mine. I may say, however, that it is an exaggeration to state that 'persons' have disappeared. Two have come to an untimely end because of the mysterious visitation, but only one can be said to have disappeared. The body of the second victim has been discovered. It was found this morning at daybreak lying at the foot of the church belfry. The poor fellow's skull had been battered in by some implement of which no trace is to be found. The other victim—the one who disappeared—was a girl of thirteen. She vanished from her father's cottage in the dead of night one week ago. Every door and window was found locked on the inside in the morning, and whatever the diabolical power may have been that spirited her away, it did so effectually; for not the faintest shadow of a clue to her whereabouts has been discovered from that hour to this."

Cleek's brows gathered, and his direct eyes lost something of their placid expression.

"This would seem to be something more serious than I had at first imagined," he said. "Would you mind giving me the full details as explicitly[Pg 29] as possible, and from the very beginning, please?"

The duke did so with as little divergence from the direct line of evidence as was consistent with the narration of a story so amazing.

"To begin with, Mr. Cleek, the origin of the affair dates back eleven months, when the engagement of my daughter, Lady Adela Fulgarney, to the young Marquis of Uppingham was first made public. I do not know if you have any knowledge of the Valehampton district or of the immediate surroundings of Essex Castle, so I must tell you that the former consists of some thirty or forty cottages with outlying farm lands, and that the latter is within easy access of St. Saviour's Church, which, with its detached belfry and surrounding graveyard, is separated from the western boundary of the castle grounds only by a narrow road upon which front two buildings, known as the Castle Cottages on account of their having been erected unintentionally within the precincts of the castle grounds years before a proper survey was carried into effect. I call attention to these two buildings because it is out of one of them that the whole perplexing mystery arises. They stand fronting upon the road which passes the churchyard, and their gardens encroach upon the castle demesne at a point about[Pg 31] ninety-six yards distant from the west wing of the castle itself. Do I make that clear?"

"Perfectly."

"I am glad of that, because it is important. In the days when the late Duchess lived she frequently begged of me to have the cottages razed, as she considered them not only an intrusion upon our privacy, but a detriment to the place in every way. I could not, however, bring myself to comply with the request, because both had been taken under lease for a term of years, and although I could, doubtless, have purchased that lease from the tenants holding it, I did not like to do so, since one of the two cottages was occupied by the aged parents of James Overton, my land steward, and they were both very loath to leave it. The other had been occupied by the wife and family of the curate of our vicar. About thirteen months ago, however, the Rev. Mr. Giles was appointed to a living of his own in Yorkshire, and took his departure after a long and pleasant sojourn with us. I could not, however, tear down the one house and leave the other standing with any benefit to the appearance of the estate, so I concluded to allow both to remain until the end of the Overton lease, at which time I proposed to demolish both. A hundred times since, Mr. Cleek, I have regretted that decision. If the cottages had to stand, I said to myself, it was as well that they should both be bringing in a revenue as for one of them to remain vacant.[Pg 32] So as the Overton lease had still six years to run I consented to my land steward finding a tenant for the one vacated by the curate for that period only.

"James Overton found a tenant almost immediately, and at that one who improved rather than detracted from the natural beauty of the castle grounds. He inhabits the place still. He is an elderly man with some small private means of his own and an absolute mania for horticulture. The result is that he makes his little garden a veritable Eden of beauty; and as there are only himself and wife, neither children nor grandchildren, and as they not only have no visitors, but hold themselves aloof from even the village folk, this Mr. Joshua Hurdon is a very desirable tenant indeed."

"So I should imagine, Duke. And your land-steward?"

"He is one of the best. Been with me for nine years. I look upon him as my right-hand man, Mr. Cleek. But that is not to the point. Efficient as he was in speedily finding a model tenant for the cottage vacated by the curate, he was not by any means successful in the case of that vacated by his parents."

"They, too, have left then, after all?"

"Yes. Old Mrs. Overton caught a chill and died about a fortnight after the Hurdons moved in, poor creature. She had gone on a visit to a married daughter in Scotland, and her death occurred there. Of[Pg 33] course, the old man could not be left altogether to the tender mercies of the village charwoman, who used to come in two or three times a week to do the rough household work, so his son, after returning from the funeral, procured him a housekeeper in the person of one Mrs. Mallory, a widow, who, with her sister, undertook the entire charge of the place and dispensed with the services of the charwoman altogether. This Mrs. Mallory appears to have been a most excellent person for the post and to have performed her duties satisfactorily, although she was of a highly romantic and even emotional disposition. She seems to have devoured love stories and cheap romances with appalling avidity. It is to her propensity for viewing life in the utterly unnatural and luridly coloured manner set forth by such literature that Valehampton owes its unhappy state to-day.

"I cannot vouch for the facts, Mr. Cleek, for I never saw the person, and never even heard of him until after his death; but, as the report goes, this romantic creature, wandering about the country lanes and dreaming her silly dreams, one day heard the sound of someone sobbing and crying out in pain. On going to ascertain the cause, she found a young man of about nineteen, evidently in the last stages of consumption, lying on his face in the woods, and a big, burly gypsy standing over him and beating him with a whip, at the same time mumbling some outlandish gibberish which the woman declared she[Pg 34] recognized at once as the spell to avert the Evil Eye.

"Well, to make a long story short, this buxom Diana of the Turnip Fields flew at the gypsy, plucked the whip from his hand, and laid it about his shoulders to such good purpose that he made off and left her with the consumptive youth. She declares, however, that before the man vanished for good he turned and shouted back to her: 'There is a curse on the creature—he is a Vampire. Evil goes with him where he lives, and evil will linger where he dies. Rivers will be choked and devils ride on the air in the place that holds his body. Children shall be stolen and the blood of them sucked by spirits, and they shall be stricken blind who cross any threshold which his accursed foot has pressed!'"

"What utter drivel!" commented Cleek, with a derisive laugh. "It is the baldest rubbish I ever heard in all my life. What happened next?"

"Well, it appears, from what I have heard, that the woman not only took pity on the unfortunate youth she had rescued, but smuggled him into the Overton cottage and tucked him away in a spare room, intending to give him a few nights' shelter and food and to build him up a bit in strength before she sent him on his way. Unfortunately, however, that night the fellow grew worse, and by the morning he was in such a bad way that she had to call in the village doctor. By that time he was dying, Doctor Forsyth declares—in[Pg 35] the very last stages of galloping consumption and beyond all possibility of saving."

"H'm! Yes, I see. Couldn't speak, I suppose? Couldn't give any account of who he was?"

"Not a syllable. Forsyth said, however, that in his eyes he looked pretty much like a gypsy himself—had all the characteristics of the Romany race. He further declared that, had he been asked, he should have said that it was well nigh a physical impossibility for the young man in his condition to have walked a step or even lifted a hand to help himself for days and days before he first saw him. But, of course, even the best of doctors are sometimes at fault in their diagnoses, and if the fellow hadn't walked—well, the woman must have got him into the house somehow."

"Yes; you are right there, Duke. The woman must have got him into the house somehow. By the way, was there any tribe of gypsies known to be in the vicinity of Valehampton at the time?"

"No, not then. There had been, a few weeks previously. But they had moved on. Why?"

"It is of no consequence. Go on, please. What happened after Doctor Forsyth's visit?"

"That night the unfortunate wretch died. Fortunately in one sense, there was no necessity for the coroner to be called in and the cottage thrown open for a general inquiry. I can tell you that James Overton was highly incensed when he heard of what[Pg 36] the woman had done; incensed at the liberty she had taken without consulting him; for, had Forsyth not been able to issue a death certificate and to declare positively the nature and cause of the disease, the result might have been serious indeed. However, the stranger died and the burial permit was issued in due form, so that put an end to any distressing business with the law. Though it didn't put an end to James Overton's worry over the matter, by any means."

"Why not?"

"Well, you see, there was the question of interring the body. In the usual course of events it would have been buried in the local potter's field with the remains of other paupers; but James Overton is a soft-hearted sort of man and—well, he didn't like to think of it ending that way, so he went to the vicar and offered to pay half the price of a grave to have the body properly buried. The other half was soon raised by subscription, and there was enough to pay for a modest headstone as well. So the poor wretch was buried in the churchyard of St. Saviour's and a cross put over the grave bearing, at Overton's suggestion, the inscription, 'Lord, I come as a stranger, but am I not known unto Thee?'"

"Very pretty, very touching. He is a man of sentiment as well as of charity, this James Overton, it would seem. So the poor wretch who 'came as a stranger' went on to where all are known. And then—what?"

"Oh, you'll scarcely credit it, Mr. Cleek. That night the church bells began to ring as though a madman had laid hands on the ropes, and the whole village was roused from sleep by their dreadful din. The vicar, thinking that someone was playing a foolish prank, dressed and went out to the belfry to reprimand the vandal, but—there was no one there! The bells were clanging and the dangling ropes moving up and down with each swing of them, but no hand was on those ropes and no living thing in sight. He climbed the belfry stairs until he came right underneath the bells themselves. There was no one there, either—they were swinging and clanging above his head apparently of their own accord! That was the beginning of the mischief, Mr. Cleek. Every night following those bells would peal out through the darkness like that. I myself have stood in the belfry and both seen and heard them do it, so the matter is not one of hearsay, but of actual experience.

"The result of this state of affairs I think you can imagine. The whole village suddenly awoke to a remembrance of Mrs. Mallory's adventure, and recalled what she had declared the vagrant gypsy had said in regard to the dead youth. The 'curse' prophesied had fallen; the 'devils' spoken of had begun to ride on the air, and in the end all the other things would happen. People with children were the first to act. They vacated their cottages and left the village by dozens. Almost the first to go was the[Pg 38] woman who was indirectly the cause of the panic—Mrs. Mallory. She and her sister fled. A fortune could not have tempted them to stay—they were simply panic-stricken. Then, hard on the heels of that, Overton's old father went so nearly daft with fright that, in common humanity, his son had to take him out of the house and send him to Scotland to the married daughter. The old man would have gone out of his mind with terror if he had not done so. The place was stripped of its equipment, the furniture sent to be sold at auction, and the cottage was left as bare and as empty as an eggshell. And so, but for a period of one brief week, it has remained ever since. But other parts of the diabolical prophecy have come to pass as threatened. The river—a branch of the lovely Colne, which flows within gunshot of the castle boundaries—has begun to choke up and there is no longer a free passage, as formerly, for the skiffs and dinghys."

"What's that? What's that?" ejaculated Cleek. "The river stopped up? Whatever by?"

"By sudden shoals which seem to have risen from the bed of it, and will permit no craft to pass. But the abominable likeness to the things predicted by the gypsy do not cease with that. He spoke of children being spirited away, and at least one child has been.

"With such a reputation hanging over it Overton could get no tenant for the cottage from which his[Pg 39] father fled in a panic. No man would live in the place rent free, indeed, no soul in all the district could be persuaded to pass by it, either by night or by day—on account of the threat of sudden blindness, and for the whole eleven months which have passed since that wretched youth was buried the place has known no tenant until eight days ago. Then there suddenly appeared—from God knows where—a man named Smale, who wandered into the district peddling rush baskets in company with his daughter, a girl of thirteen. He heard of the place, laughed at its reputation. He was homeless and well-nigh penniless; he wanted a shelter, and was willing to risk anything to find one. He went to Overton, but Overton had not the heart to yield to his entreaties, so he finally came to me in person. If I would let him have the house rent free for six months, he'd live in it and brave all the spirits that ever existed. I listened and—yielded. Eight days ago the man and the child took possession. A week ago this very night the child vanished—in the dead of the night, with all the doors and all the windows fast bolted on the inside. After two horrible days of rushing about and wildly trying to find a trace of her, the father went insane, flung himself into the river, and was drowned.

"Nor have the tragedies ceased with these two terrible things, Mr. Cleek. The bridesmaids and the guests for my daughter's forthcoming wedding have arrived at the castle. Among them is Captain[Pg 40] Weatherley, and with him came his soldier servant—a loyal and intrepid fellow named Davis, who had been through countless perils with his master, and was afraid of nothing living or dead. Early this morning he was found by the Vicar at the foot of the belfry. His head had been smashed in, and he was beyond all earthly aid."

"Any attempt been made to decide the matter? Upon the part of the local authorities, I mean; for, of course, they would be notified of the affair."

"Naturally. The vicar attended to that. But beyond the fact that the body was removed by them to the morgue attached to the local almshouses, I know nothing whatsoever of their movements; nor do I quite see how they could have come to any definite conclusion about the affair."

"No doubt, however, their first step would have been to investigate the condition of the earth in the immediate vicinity of the cottage," suggested Cleek.

"Ah! I see what you mean. They might have found traces of footprints, you think?"

"Something of that sort—yes. If it had rained recently, to put the ground in a condition to receive and retain an impression——"

"The dead man's boot might have been fitted to it, and the point established that way," put in Mr. Narkom, somewhat hastily, his mind travelling along well-worn grooves.

"Oh! no," said Cleek. "Not necessarily a footprint at all, Mr. Narkom, and certainly not a booted one. A boot is never conclusive proof of the identity of the wearer. It may be removed for the purpose of creating certain impressions and afterward returned to the body of the owner. Contrary to the methods of the fictionists, the imprint of a boot or shoe is of no possible value as a clue whatsoever. The only footprints that can be relied upon to furnish positive evidence of the personality of their author are those made either by an animal or the human foot when it is absolutely bare."

"But bare or booted, Mr. Cleek," interposed the duke, "neither could be relied upon to establish—were it important to do so—any proof relative to the movements of Captain Weatherley's servant in the neighbourhood of that abandoned cottage. Two circumstances render such a proceeding impossible. You suggested a moment ago that—well—er—something might be discovered in the immediate vicinity of the cottage provided it had rained recently. Well, it has not. As a matter of fact, the county has been suffering from an absolute drought for the past five weeks, and the earth is baked as hard as flint. That is the one circumstance; the other is even less promising. Both cottages—that of the Hurdons and that left vacant—have courtyards entirely paved with red tiles. A broad, red-tiled footpath surrounds each building, and runs down the middle of its accompanying[Pg 42] garden. Nor is that all. Even the belfry of St. Saviour's itself could not have furnished any evidence of the man ever having been there had not his body been found on the spot. It is a curious old Norman structure which originally stood in the midst of a sort of 'square,' paved with cobbles, and extending outward from the walls of the tower for a distance which, roughly, is about four yards in every direction. The uneven surface presented by these cobbles after ages of wear having proved dangerous walking for the thick-soled boots of the bellringers, had caused more than one of them to have a nasty fall, so the vicar sought to rectify the matter by having them entirely covered by a thick layer of cement. The result is that the square in the middle of which the belfry stands presents a smooth, firm, level surface as hard as iron and as bare as one's hand. An elephant could not leave a footprint upon it, much less a man."

The duke paused a moment, as if to give due weight to these unpromising circumstances, then leaned back in his chair.

"There," he said, "that is the case as it stands, Mr. Cleek."

"A very interesting little problem," said Cleek, studying his finger-nails as if the condition of them was of moment. "You are not, sir, I take it, inclined to share the general belief obtaining in the village, and to attribute these remarkable doings to any supernatural agency?"

"Certainly not," the duke replied. "That would be the very height of absurdity. It must certainly be apparent to anybody with an ounce of common sense that there is not only a human brain engineering the affair, but that there is behind it a definite purpose."

"Beyond all question."

"Yes, but what? That is the point. What end can be attained, what purpose served by a proceeding of this nature? That is the inexplicable part of it. Were it not for the disappearance of the child and the murder of the man, it would be but one degree removed from farce."

"Quite so," admitted Cleek, still studying his finger-nails. "But the elements of farce come perilously near to the borderline of tragedy at times;[Pg 44] and we have it upon the best authority that it is but a step from the sublime to the ridiculous. Besides, when one has large landed interests—— H'm! Yes. By the way, I see that, despite all the rumours to the contrary, you have finally decided not to take a place on the board of directors of the company formed for exploiting the new cement which is to make the present variety as obsolete as the mud bricks of the Early Britons. Septarite it is called, is it not? I see that the company's prospectus is out and that the name of the Duke of Essex is not upon it."

"No; it is not," admitted the duke, with some heat. "Its mention in that connection was an unwarranted presumption. The thing had merely been broached to me in the most casual manner, and while I was considering the project my name was made use of in the most flagrant manner to bring the company before the public."

"I fancy I have heard that it was the present chairman of the board, Sir Julius Solinski, who was responsible for that."

"It was. And a piece of infernal impertinence it was, too! Geological borings have established the fact that there is in all probability a large deposit of septaria underlying a tract of land which I own in the village, and the man approached me with a proposition to sell or lease it to his wretched company for a term of years. As the land was practically of no[Pg 45] importance to me, I told the fellow that I would consider the matter, and on that basis he made the most flagrant misuse of my name to bolster up his pettifogging business. Of course, I immediately declined to have any further dealings with him, and that settled the affair altogether."

"Unless by one means or another—depreciated value, a deserted village, something of that sort—he might, in time, bring you round to another way of thinking," said Cleek, quietly.

The duke sat up sharply. It was impossible not to catch a hint from that line of argument.

"Do you mean to say that he—that that pettifogging fellow—— The thing is monstrous, Mr. Cleek, monstrous! If that's the little game—if his is the hand that's behind the thing——"

"Pardon, but I have not said that, Duke. It is possible, of course, and there is a suggestiveness about it which—— Oh! well, I shall know more about that when I go down to Valehampton and look into the matter at close quarters. And now may I venture to ask a question touching upon more personal matters? I distinctly remember reading that, at the time of making known Lady Adela's engagement eleven months ago, you chose the opportunity to declare also your intention of taking another wife. Is that so?"

"It is perfectly true. The fact is now public property. If all goes as planned, I shall be married to[Pg 46] Lady Mary Hurst-Buckingham this coming autumn."

"I see. One other question, please. Your first marriage never having been blessed by a son, the heir to your title and estates—failing, of course, direct issue in the future—is, I believe, the son of a distant cousin, one Captain Paul Sandringham?"

"That, too, is true."

"You have no very great respect for that gentleman, I imagine. Is that a fact?"

"Your pardon, Mr. Cleek," replied the duke, stiffly. "I am afraid I cannot enter into a discussion of my personal affairs. They cannot concern Scotland Yard, nor have any bearing upon the matter in hand."

"That, I fear, Your Grace," said Cleek quietly, "is a matter upon which I may be the better judge. One should be as frank with one's detective as with one's doctor. Each has the greatest interest in being able definitely to lay his finger upon the root of a disease, and each may become useless if perfect confidence be not given with regard to all points."

"I ask your pardon, Mr. Cleek. I did not at first see it in that light. I admit it then: I have no respect for Captain Sandringham—none whatever. He is a person of dissolute habits and very questionable ways. He left the Army under compulsion, but he still retains the title of 'Captain.' People of any standing, however, no longer receive him."

"So that, naturally, he will not be invited to share in the festivities in connection with Lady Adela's wedding?"

"Most emphatically he will not! I have not written to him, spoken to him, nor even seen him these ten years past. That, however, would not prevent his inheriting both the title and estates were I to die without male issue. I have not the slightest doubt that he has raised money on the anticipated reversion, which he will now, of course, be obliged to pay back. I don't know how he will manage it, nor do I care."

"H'm! Yes! I see! So then your marriage would be something in the light of a severe blow to the gentleman, of course. In England is he?"

"I haven't the faintest idea. The last I heard of him he was on the Continent somewhere. But that was ten years ago, and I have forgotten the exact place. It would be where there is gaming and life of that sort, of course."

"Quite so—if one is given to that sort of thing. Mr. Narkom!"

"Yes, old man?"

"Don't happen to know the market price for fullers' earth in bulk, do you?"

"Good lord, no! Why, what in the world——?"

"I should like about fifteen or sixteen pounds of the ordinary variety—not the bleached sort, you know," interposed Cleek, rising. "You might 'phone[Pg 48] through to the Yard and order it. And, by the way, I'm afraid you won't be able to join Mrs. Narkom at dinner this evening, after all. We shall spend the night at Valehampton. And now, before I set out to look into the matter of this engaging little affair, Duke, one last question, please. Did you take anybody into your confidence regarding this visit to London to-day?"

"Yes, naturally. I spoke to the Marquis and to Captain Weatherley about it, of course; and—yes—to Overton. I fancy I may also have mentioned it while Carstairs was present; he was coming in and out of the breakfast room a great deal, of course. He's the butler."

"H'm! Yes, I see! You wouldn't mind letting it be understood when you go back, would you, that a couple of ordinary Yard men have been put on the case? Just ordinary plain-clothes men, you know—called—er—let us say, 'George Headland' and 'Jim Markham.' Can you remember the names?"

"I can and I will, Mr. Cleek," the duke replied, stopping to write them down on the margin of a newspaper lying on a table beside him.

Cleek stood and watched the operation, explaining the while that he should like the names to get into circulation in the village; then, after having obtained permission to call at the Castle and interview the duke whenever occasion might arise, he took his[Pg 49] departure in company with Mr. Narkom, and left their noble client alone.

"Rum sort of a case, isn't it?" remarked the Superintendent as they went down the stairs together.

"Very. And it will depend so much upon what they are. Geraniums, lilies, pansies!—even roses. Yes, by Jupiter! roses would do—roses and fuchsias—that sort of thing."

"Roses and—— My hat, what the dickens are you talking about?"

"Let me alone for a minute—please!" rapped out Cleek. "I say—you'd better tell Hammond and Petrie to bring that bag of fullers' earth with them instead of sending it. Have them turn up with it—both of them—at the King's Head, Liverpool Street, as soon as they possibly can. The light lingers late at this time of the year, and the limousine ought to get us down to Valehampton before tea time if Lennard makes up his mind to it."

If you have ever journeyed down into Essex by way of the Great Eastern from Liverpool Street, you may remember that just before you come to Valehampton—six or seven miles before, in fact—the train stops at a small and exceedingly picturesque station bearing the name of Willowby Old Church, behind which the village of the same name lies in a sort of depression, a picture of peaceful beauty.

But if you do not recall it, it doesn't matter; the point is that it is there, and that at a period of about two and a half hours after Cleek and Mr. Narkom had left His Grace of Essex there rushed up to the outlying borders of that village a panting and dust-smothered blue limousine in which sat four men—two on the front seat and two on the back. And the remarkable fact about it was that the two "back seaters" looked so nearly the image of the two "front seaters" that if you hadn't heard all four of them talking you might have fancied that at least one pair was seated in front of a looking-glass.

They differed not a particle in anything, from sleek, well-pomaded hair to bristly, close-clipped[Pg 51] moustache, or from self-evident "dickey" and greasy necktie to clumping, thick-soled, well-polished cow-hide boots with metal "protectors" on the heels—policemen's boots by all the signs.

"Safe enough here, sir, I reckon," came through the speaking tube from the chauffeur as the car halted in the shadow of some trees. "No one in sight, and the station not more than a hundred yards away—get to it in two minutes without half trying."

The pair on the back seat pulled farther back from observation and the pair on the front one rose and got out. The last to do so spoke a few sentences to the chauffeur.

"The train won't be in for another half-hour yet," he said. "You ought to be in Valehampton before that. Keep out of sight as much as possible. You won't have much difficulty in finding out where we put up, and when you do, keep as close to the neighbourhood as you can with safety. Meanwhile, impress it upon Hammond and Petrie not to pull down the curtains, but to keep out of sight, if they have to lie on the floor to do it. Come along, Mr. Narkom. Step lively!"

"All right, sir," said Lennard; then the limousine flashed away, bearing the original Hammond and Petrie in one direction while the counterfeit presentments of them walked off in the other.

In half an hour the down train from London arrived. They boarded it, and went, with their brier-woods[Pg 52] and their shag, into a third-class smoking compartment, and were off a minute or so afterward.

The sun had not yet dropped wholly out of sight behind the west wing of Essex Castle when they turned out at Valehampton, and they had only got as far as the door where the ticket collector stood when a voice behind them said abruptly: "Mr. Headland—Mr. Markham. One moment, please." Facing round they saw a pleasant-faced man on the right side of forty coming into the waiting-room from the platform, and advancing toward them. His clothing was undeniably town-made, and selected with excellent taste. He wore tan boots and leather puttees, and carried a hunting crop in his hand. He came up and introduced himself at once as James Overton, land-steward of the Duke of Essex.

"Hallo! The duke got back a'ready, has he?" asked Cleek, when he heard this.

"Oh, no. I do not expect him for quite another hour at the very earliest. He will come down as he went up—in the motor. And he is always a little uneasy about travelling fast. It was at Captain Weatherley's suggestion that I telephoned him at the Carlton to inquire if there was any likelihood of somebody from Scotland Yard being sent down before morning. That is how I came to know—and to be here. His Grace informed me that you had already started. The local time-table told me the rest."

"Good business! But I say, Mr. Overton, what put it into Captain What's-his-name's head to have you telephone the duke and inquire? Nervous gent, is he?"

"No; not in the least. He suddenly remembered that the only inn in the village closed its doors this morning. Last night's affair finished the landlady. She cleared out, bag and baggage, at noon. Couldn't be hired to stop another hour. The Captain thought I ought to telephone to His Grace and make the inquiry, because if anybody should be coming down to-night something ought to be done to find lodgings beforehand."

"I see. Nice and thoughtful of the gent, Markham—eh, what? Much obliged to you for the trouble, I'm sure. Did you manage to find us any, then?"

"Yes, Mr.—er—Headland, will it be? Thanks.... I had some difficulty in doing so for a time; but finally Carstairs came to the rescue. Carstairs is His Grace's butler. He is engaged to a young woman living on the other side of the village, and her people have eased matters up a bit by placing a room in their cottage at the disposal of Mr. Markham and yourself. Shall I show you to it? I regret that I was thoughtless and neglected to speak for a conveyance."

"Oh, that doesn't matter," replied Cleek, knocking out his pipe against his heel. "My mate and me,[Pg 54] we're used to hoofing it; and, besides, it'll be a change to stretch our legs after being cooped up for nigh three hours in the train. Wot price Shanks's mare for a bit, Jim? Agreeable?"

"Hur!" grunted Mr. Narkom, nodding his head in the affirmative without troubling to remove his pipe from his lips.

"Right you are, then—best foot forward. Mustn't mind Markham's little ways, Mr. Overton. Some folks get the idea that because he doesn't talk much the beggar's sullen. But that ain't it at all. Fact is, he's a bit hard of hearing. Shell in the South African War. Busted ear-drum."

"What, deaf?"

"Yessir. Deaf as a blooming hitching post in the left ear, and the right one not up to no great figger, either. A thundering good man though, one of the best."

"God bless my soul! Deaf, and yet——"

Here Mr. Overton's voice dropped off suddenly, and he did the rest of his thinking in silence. The thoughts themselves were anything but complimentary to a police force which retained deaf men on its active list and could send out nothing better than this precious pair of illiterates to investigate an important case.

"The duke does some funny things sometimes," he said to himself as he walked over to the spot where he had tethered his horse and began to unfasten[Pg 55] it. "And that's what Scotland Yard takes the rate-payers' good money to support, eh? Good lord!"

He rejoined the two undesirables a moment later, and with the horse's bridle over his arm, walked on beside Cleek while Mr. Markham dropped back a few paces into the rear and clumped along in heavy-footed, listless style.

Mr. Overton, too, was silent for a time—as if the apparent inefficiency of these two upon whose perspicacity the duke was relying rather weighed upon his spirits, and he saw little more hope of getting to the bottom of this perplexing affair than if it had been left to the local constabulary. Cleek was sorry for that. He could see that the man was of a hearty, jovial disposition, and likely to be a rather pleasant companion for a long walk. He therefore set out to put him more at his ease and to start the conversational ball rolling.

"Fine country this, Mr. Overton," he said, looking round over the wide sweep of green land. "Reminds me of Australia, them trees and fields. Though I never was there; but I've seen the photographs. Brother's a sailor on the P. and O.—fetched back heaps of 'em. Hello! Wot price that church spire away over there to the left? Will that be St. Saviour's?"

"Yes."

"Church where the goings on takes place, ain't it?[Pg 56] The bell-ringing and the like. Reckon I must have a look at that place some time to-morrow."

"Not until to-morrow, Mr. Headland?"

"Well, you see, I didn't expect that the box containing our magnifying glasses and camera for taking photographs of fingerprints and things of that sort, you know, will arrive before then, and it's no use working without your tools, is it? Superintendent said he'd ship it down to us either to-night or the first thing in the morning, and he's pretty prompt about such things."

"So then, of course—— To-morrow, eh? I suppose you haven't formed any opinion regarding the genesis of the case, Mr. Headland?"

"The which, sir?"

"The genesis, the start, the beginning, the cause."

"Oh! I see. No, I haven't made up my mind so set that it ain't liable to be changed. I never was one of them pig-headed sort that gets an idea and then can't be shook off it. I've formed a sort of general notion regarding it, you know, but, as I say, nothing fixed."

"I see. Would it be too much to ask what the 'general notion' is?"

"Why, it'll be just what that dead chap—the one that was killed last night—called it: a case of hanky-panky. Somebody is engineering the business. For a purpose, you know. Depreciating land values for the sake of getting hold of that piece of property[Pg 57] the cement company wants to get from the duke."

Mr. Overton stopped short.

"I hadn't thought of that!" he declared. And it was clear enough from the manner in which the blood drained out of his face, and then came rushing back again, that he never had.

"Hadn't you?" said Cleek, with a slight swagger. "Lord, I did—the first thing!"

It was evident that this hitherto unthought-of explanation had a remarkable effect upon Mr. Overton.

"It would be that Hebrew chap, the company promoter who was knighted last New Year, Sir Julius Solinski," he said as he resumed the walk. "It would be that fellow who would be at the bottom of any scheme to acquire the land; and the man has a country seat in the adjoining district. Yes, but the bells, Mr. Headland—the bells?"

"Oh, that will be the doing of boys. Up to a lark, you know. A blackened fishing-line carried over the branch of a tree—that sort of thing. Did it myself when I was a youngster. It's all tommyrot about it's being a 'spirit,' you know. Drivel."

"You think so?"

"Why, cert'nly. Don't you?"

"I did once," replied Overton, sinking his voice. "I changed my mind upon that score last night. I'd have stopped that chap, Davis, going to the belfry if I had known in time. I didn't. I was over at[Pg 58] Willowby Old Church on business connected with the estate. I was kept later than I had expected, and didn't get back to Valehampton until after dark."

His voice dropped off. He walked on a few steps in silence, his face curiously grave, his eyes very large. Of a sudden he took a slight shivering fit—the last thing in the world one would have expected of such a man—and then threw a nervous glance over his shoulder and looked up at Cleek.

"Mr. Headland," he said, gravely, "heretofore people have merely heard things. Last night I saw!"

"Saw? Saw what?"

"I don't know. Perhaps I never shall. I can give it neither name nor description. I only know that whatever it was it certainly was nothing human."

"A ghost?"

"It was a jolly good imitation of one then, if it wasn't. Up to that minute I had been as certain as you are that human hands, and human hands alone, were at the back of this diabolical business, and that the talk of the bells being rung by spirits was the baldest rubbish in all the world. To-day I don't know what to think! It wasn't a case of nerves. I didn't imagine the thing. I'm not that kind of man. I saw it, Mr. Headland—saw it as plainly as I now see you."

"I say, you know, you make my flesh crawl. How did it happen? And where?"

"In the road on the far side of St. Saviour's, at about half-past ten last night," said Overton, with grave seriousness. "I was coming up over the slope between Valehampton and Willowby Old Church, intending to turn off at the crossroads and take the short cut to the Lodge, where I live. The moon was shining brightly and there was no air stirring. The trees were as motionless as wooden things, and the road, after the long drought, was baked like iron. Had any footstep fallen upon it I must have heard it in that complete quiet. Had any living creature passed me in the road, that creature I must have seen. I saw and I heard nothing.

"All of a sudden, just as I got to the top of the slope, I happened to look up and catch sight of the flat top of the bell tower of St. Saviour's. I was a goodish bit away from it, but there was a break in the roadside trees at that point and I could see it clearly. I shouldn't have given it a second glance under other circumstances, for I am quite used to the sight of it and, up to that moment, never had the slightest belief in there being anything supernatural connected with it in any way. But it so happened that a curious thing about it forced itself upon my notice at that moment, so I stood still and looked at it fixedly. The curious thing was this: at the very moment when I first looked up and saw the tower's top, the moon dipped out of sight behind a passing cloud. The place should, naturally, have been[Pg 60] plunged into darkness; instead a curious blob of light still lay on the roof of the place, as if the moon still shone upon some circular silver thing that rested there.

"I could not make it out. There is no metal on the belfry's top. Like all towers of the Norman type, it is simply a huge, truncated stone cylinder, roofed over with stones and pierced here and there with bowman's slits cut in the circular walls. But suddenly, to my immense surprise, that curious light began to move; then, presently, it went circling round and round the tower's top at a terrific rate of speed.

"'O-ho,' said I to myself, thinking, of course, that I had had the rare good fortune to stumble upon the spot at a moment when the person responsible for the ringing of the bells was on the ground for some purpose of his own. 'Well, I'll precious soon make short work of you, my friend, I promise you that.' I had not spoken any louder than I am speaking now, Mr. Headland, so it would have been utterly impossible for any one or anything on the tower's top to have heard me all that distance away. But I swear to you that in the very instant I spoke those words and made to cut across into the graveyard of St. Saviour's a sudden gust of wind as furious as a tropical hurricane seized upon the trees about me and whipped and twisted them into writhing cones of green; a dozen unseen hands slapped and tore at me and flung me back; and the light on the belfry's top lurched out[Pg 61] into space and came careering toward me with a shrieking noise. I saw for a moment the outlines of a frightful, bodiless, inhuman face, wrapped in streaming ribbons of light, and then the thing rushed by me in the darkness, shapeless and screaming, and for the first time in my life I fainted."

Cleek made not a single sound. A curious, intense, half-frightened expression had settled down over his face. He walked on with brows knit and eyes fixed on the road, and when Overton, impressed by his silence, looked round at him, he saw that his lower lip was pushed outward beyond the upper one, and that the pipe he had taken out and refilled hung from the corner of his mouth still unlighted.

"It was a shocking experience, Mr. Headland," Overton said, fetching a deep breath.

"Must have been," admitted Cleek, without looking up. "You're putting some new ideas into my head, Mr. Overton. If it had been one of the villagers, or even a servant from the Castle—anybody but you! H'm! Wot happened afterward?"

"When I came to I was lying on my back in the road. The wind had died utterly away, the trees were standing motionless again, but there was a curious sound as of wheels passing and repassing me at a furious rate. There was, however, not a moving thing in sight, and as the moon was again shining[Pg 63] brightly I could see quite clearly. Nevertheless, frightened as I was—and I confess that I was frightened, Mr. Headland, horribly so—I struck several matches and examined the surface of the road thoroughly."

"Why?"

"I had heard of those phantom wheels that were said to rush about the village by night, but this was my first personal experience with them. To judge by the sound alone, I should have declared that vehicles on rubber tyres were scudding past me at the rate of five or six a minute and almost within touching distance. When I struck those matches and looked at the white dust of the road, there was nothing on it but the prints of my own feet and a shapeless mark where I had fallen. The wheels, however, were still speeding by in an unbroken stream of traffic. I turned tail and ran as I haven't run since I was a boy, and I never slackened pace either, until I was safe inside the Lodge and the door bolted behind me. If I had had a bit of pluck just then, I should have faced the dark avenue up to the Castle and told about the affair. I wish now that I had. It would have saved that poor chap's life."

"Maybe, but you can't be sure of it, Mr. Overton. He was a daredevil sort from what I've heard, and you can't do much with them kind of chaps when they take a notion in their heads."

"Possibly not. Still, I might have tried. I shall[Pg 64] never be quite able to forgive myself for being such a coward. But I was absolutely in a blue funk, and wouldn't have faced that long walk up the Oak Avenue for the best thousand pounds I ever saw."

"Say anything to the duke about it?"

"No. I was going to do so, but this morning, when poor Davis's body was found, His Grace was in something so very like a panic over the horrible turn the abominable affair had taken, that I hadn't the heart to harrow up his feelings still further—particularly as he was determined on going up to town and putting the matter into the hands of Scotland Yard at once. I shall do so, of course, when he's calmer. It is no use making matters worse than they are. It is bad enough to feel that you have to cope with natural forces without dragging supernatural ones into it. And there is some supernatural force connected with it, Mr. Headland—I'm convinced of that now. Human beings may engineer a plot to haunt a village for some purpose; may even brain a man and spirit away a child to keep what they are up to from being found out—but they can't make church bells ring without hands, nor wheels fly through dust without leaving traces. Nor can they produce that monstrous Thing which I saw with my own eyes last night."