| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/pacificationofbu00crosrich |

Click on the maps to display a high-resolution image.

THE PACIFICATION OF BURMA

BY

SIR CHARLES CROSTHWAITE, K.C.S.I.

CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF BURMA, 1887-1890

MEMBER OF THE COUNCIL OF INDIA, ETC., ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

LONDON

EDWARD ARNOLD

1912

(All rights reserved)

Upper Burma was invaded and annexed in the year 1885. The work hardly occupied a month. In the following year the subjugation of the people by the destruction of all formidable armed resistance was effected; lastly, the pacification of the country, including the establishment of an orderly government with peace and security, occupied four years.

As head of the civil administration, I was mainly concerned with this last phase.

It would be a difficult task to give a continuous history of the military operations by which the country was subjugated. The resistance opposed to our troops was desultory, spasmodic, and without definite plan or purpose. The measures taken to overcome it necessarily were affected by these characteristics, although they were framed on definite principles. A history of them would resolve itself into a number of more or less unconnected narratives.

A similar difficulty, but less in degree, meets the attempt to record the measures which I have included in the term "pacification." Certain definite objects were always before us. The policy to be followed for their attainment was fixed, and the measures and instruments by which it was to be carried out were selected and prepared. But I have found it best not to attempt to follow[vi] any order, either chronological or other, in writing this narrative.

My purpose in writing has been to give an intelligible narrative of the work done in Burma in the years following the annexation. It was certainly arduous work done under great difficulties of all kinds, and, from the nature of the case, with less chance of recognition or distinction than of disease or death. The work was, I believe, well done, and has proved itself to be good.

My narrative may not attract many who have no connection with Burma. But for those who served in Burma during the period covered by it, whether soldiers or civilians, it may have an interest, and especially for those still in the Burma Commission and their successors.

I hope that Field-Marshal Sir George White, V.C., to whom, and to all the officers and men of the Burma Field Force, I owe so much, may find my pages not without interest.

I have endeavoured to show how the conduct of the soldiers of the Queen, British and Indian, helped the civil administration to establish peace.

I believe, as I have said, that our work has been successful. The credit, let us remember, is due quite as much to India as to Britain. How long would it have taken to subjugate and pacify Burma if we had not been able to get the help of the fighting-men from India, and what would have been the cost in men and money? For the Burmans themselves I, in common with all who have been associated with them, have a sincere affection. Many of them assisted us from the first, and from the Upper Burmans many loyal and capable gentlemen are now helping to govern their country justly and efficiently.

It has been brought home to me in making this rough[vii] record how many of those who took part in this campaign against disorder have laid down their lives. I hope I may have helped to do honour to their memories.

I have to thank all the kind friends who have sent me photographs to illustrate this book, and especially Sir Harvey Adamson, the present Lieutenant-Governor, for his kindness in making my wants known.

February, 1912.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA | 1 |

| II. | THE CHIEF COMMISSIONERSHIP OF BURMA | 19 |

| III. | UPPER BURMA | 30 |

| IV. | MANDALAY | 37 |

| V. | DEALING WITH DACOITS | 60 |

| VI. | CIVIL AND MILITARY WORKS | 66 |

| VII. | A VISIT TO BHAMO | 74 |

| VIII. | DISARMAMENT | 80 |

| IX. | TROUBLE WITH THE WUNTHO SAWBWA | 90 |

| X. | MILITARY REPLACED BY POLICE | 95 |

| XI. | BURMA BECOMES A FRONTIER PROVINCE | 100 |

| XII. | DACOITY IN THE MINBU AND MYINGYAN DISTRICTS | 107 |

| XIII. | TROUBLE IN THE MAGWÈ DISTRICT | 115 |

| XIV. | GRADUAL CREATION OF AN EFFICIENT POLICE FORCE | 128 |

| XV. | THE SHAN STATES | 133 |

| XVI. | THE SHAN STATES (continued) | 160 |

| XVII. | THE KARENNIS, OR RED KARENS, AND SAWLAPAW | 188 |

| XVIII. | THE TRANS-SALWEEN STATES | 209 |

| XIX. | BHAMO AND MOGAUNG | 234 |

| XX. | BHAMO, THE SOUTHERN TOWNSHIPS, AND MÖNG MIT | 268 |

| XXI. | THE CHINS | 287 |

| XXII. | THE CHIN-LUSHAI CAMPAIGN | 308 |

| XXIII. | INTERNAL ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA | 337 |

| INDEX | 343 |

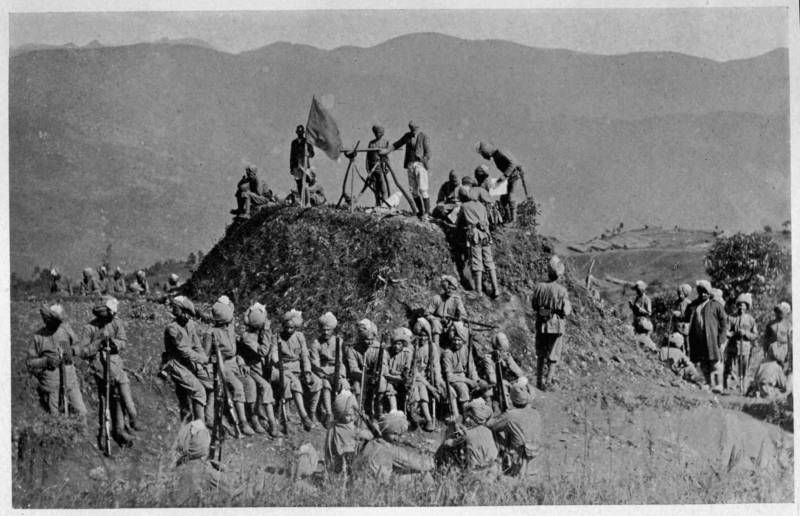

| PICKET ON THE CHIN HILLS | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

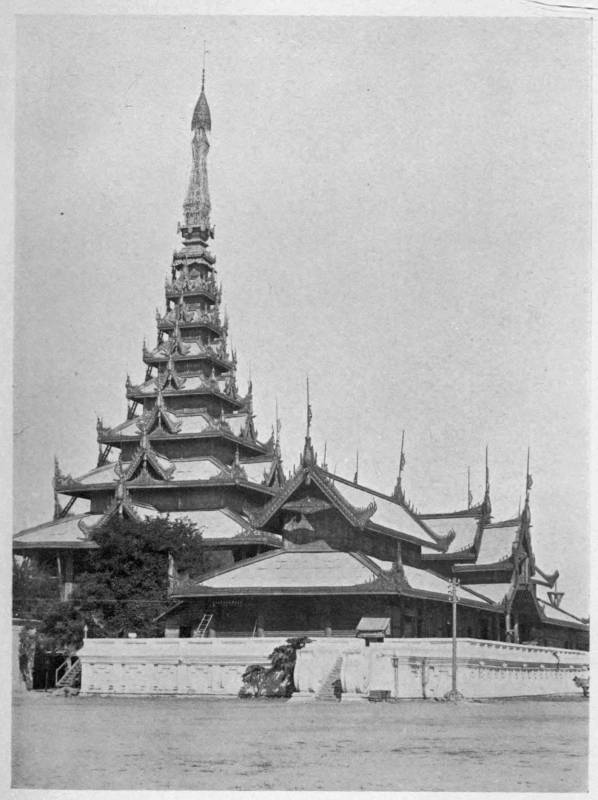

| THE PALACE, MANDALAY—"CENTRE OF THE UNIVERSE" | 6 |

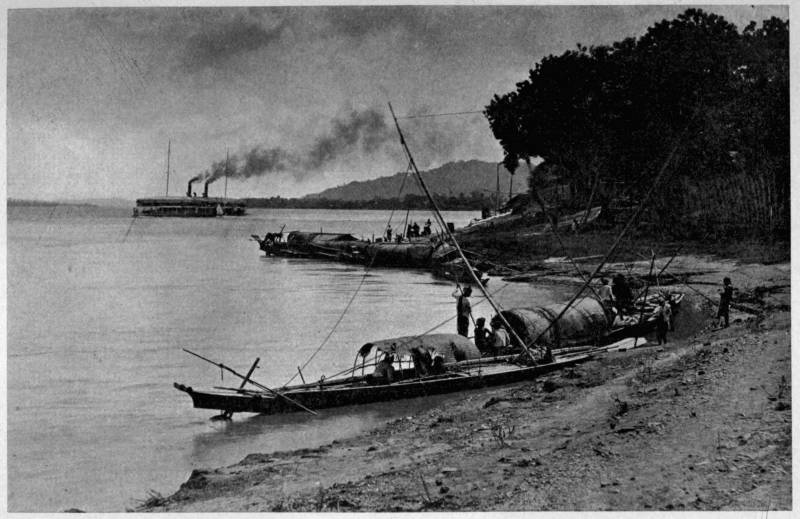

| THAYETMYO—MAIL STEAMER LEAVING | 26 |

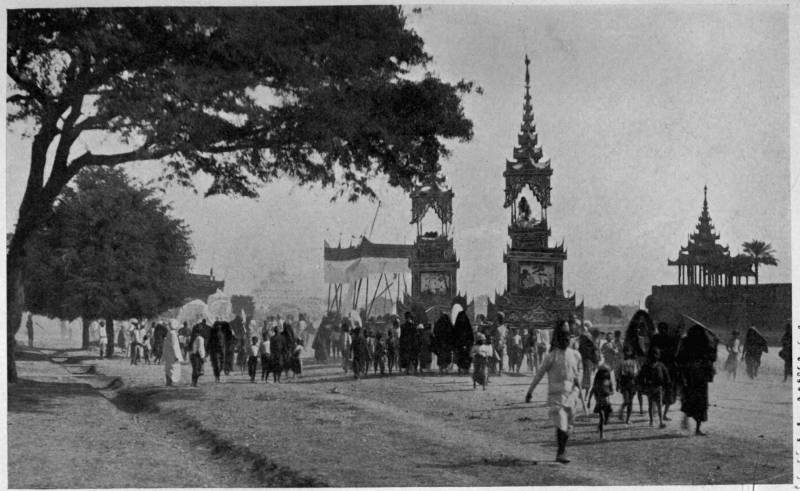

| A PONGHI'S FUNERAL PROCESSION | 38 |

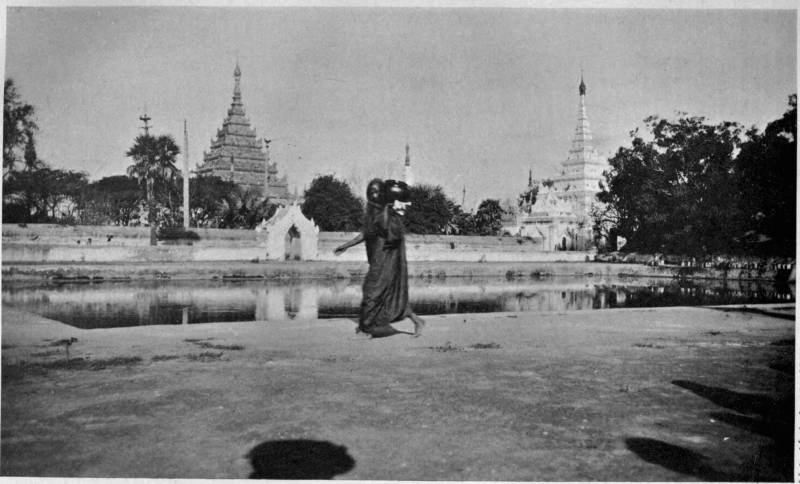

| MANDALAY | 48 |

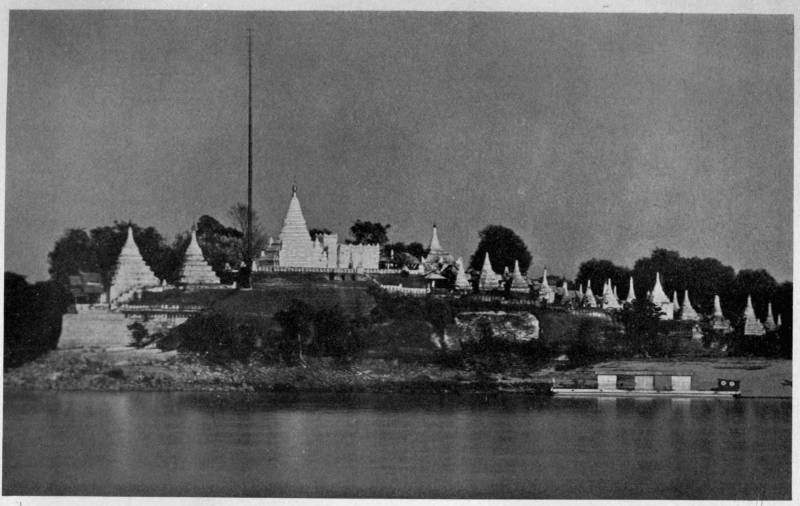

| SHWÈTAKYAT PROMONTORY OPPOSITE SAGAING | 64 |

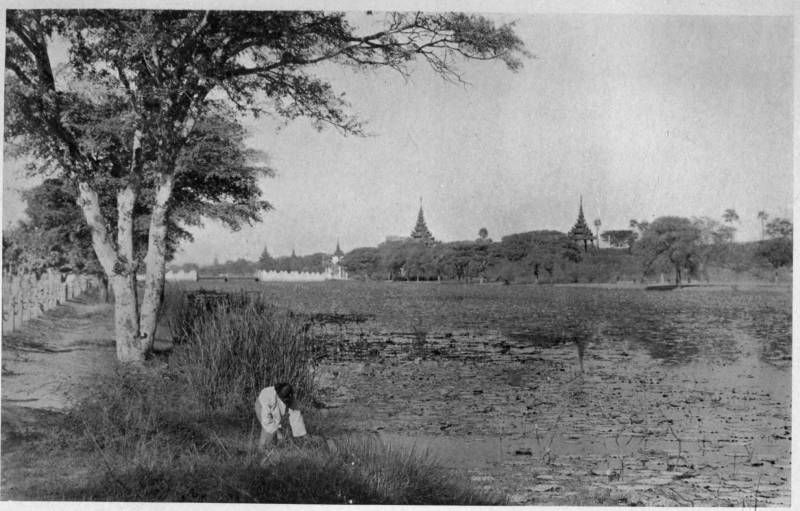

| "THE MOAT," MANDALAY, AND NORTH WALL OF FORT DUFFERIN | 70 |

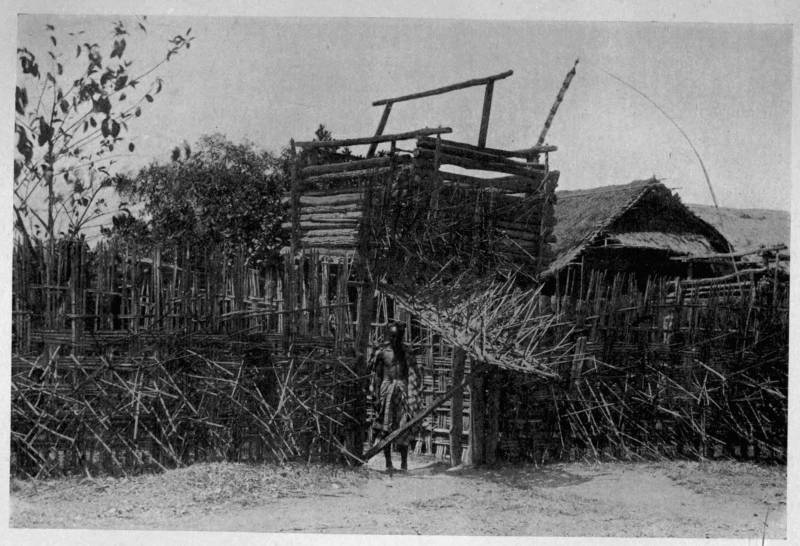

| OUTER BAMBOO STOCKADE OF BURMESE FRONTIER VILLAGE | 86 |

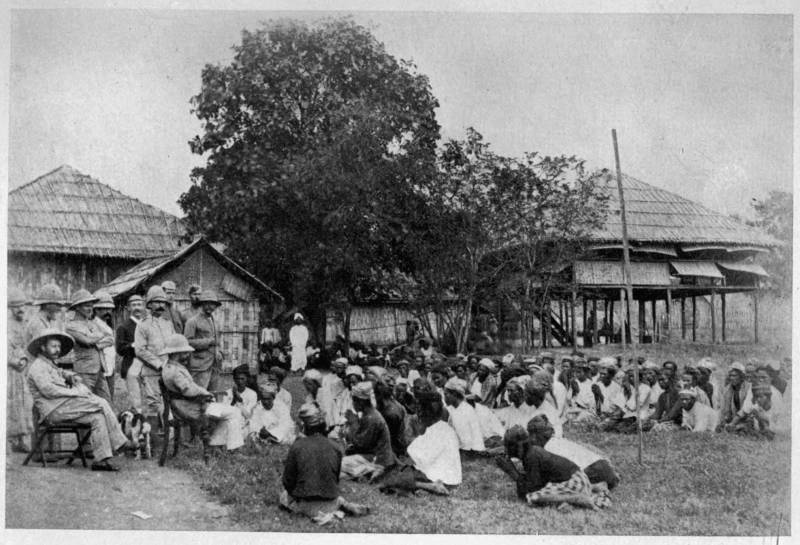

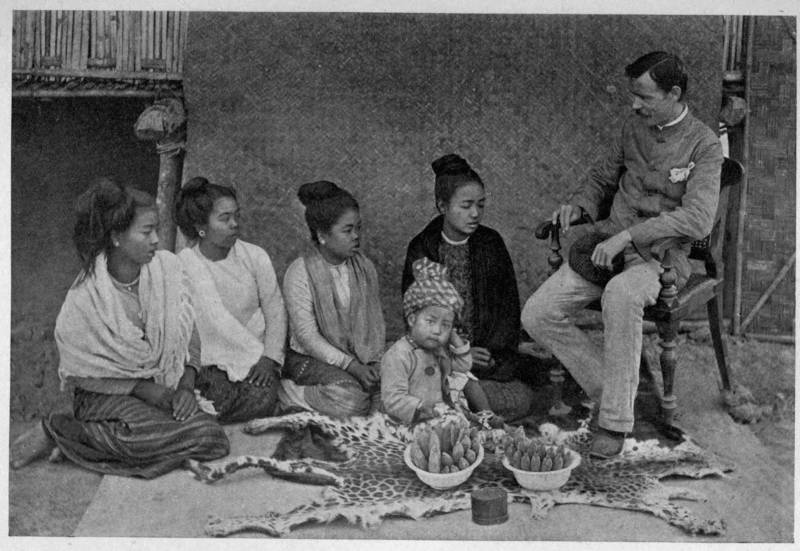

| CONSULTATION OF VILLAGE HEADMEN WITH CHIEF COMMISSIONER | 90 |

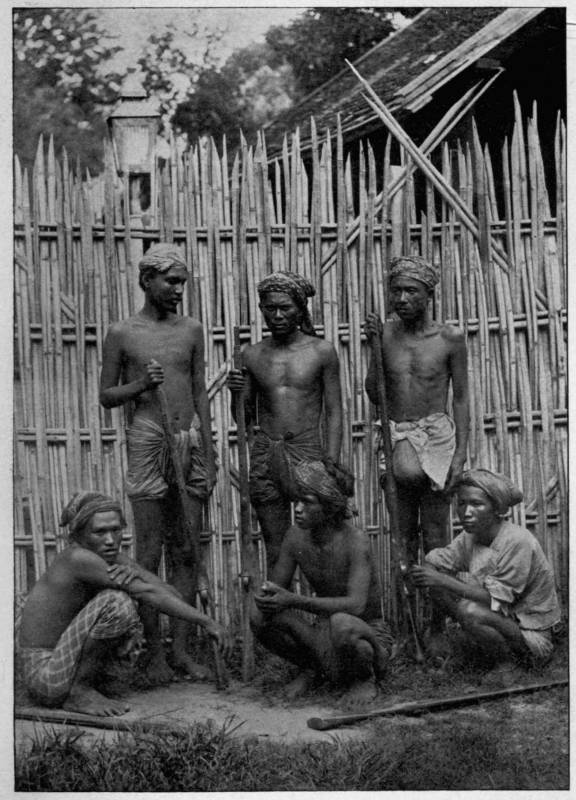

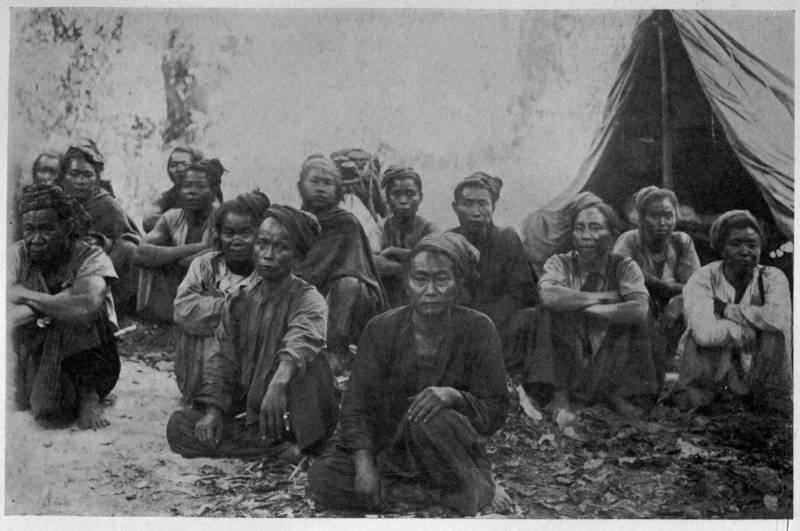

| BURMESE DACOITS BEFORE TRIAL-WORST CHARACTERS AND | |

| NATIVE POLICE GUARD | 110 |

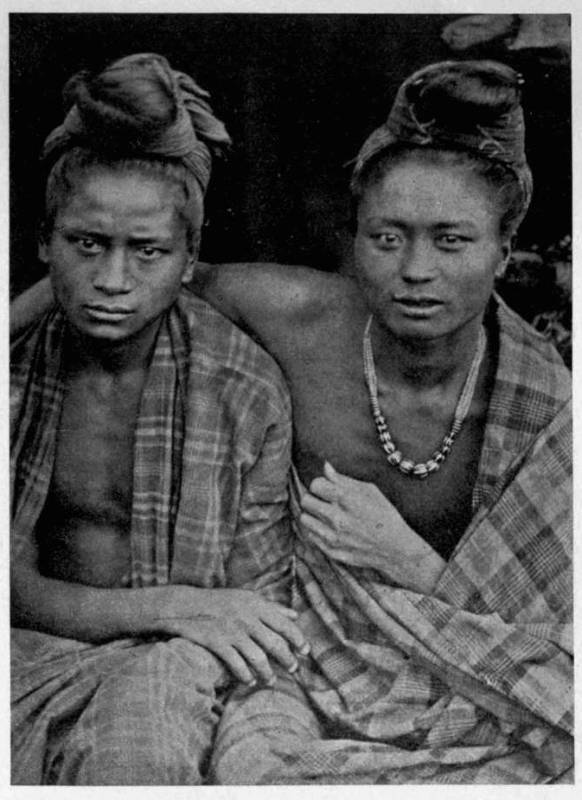

| SAW MÖNG, SAWBWA OF YAWNGHWÈ, AND HIS CONSORT | 142 |

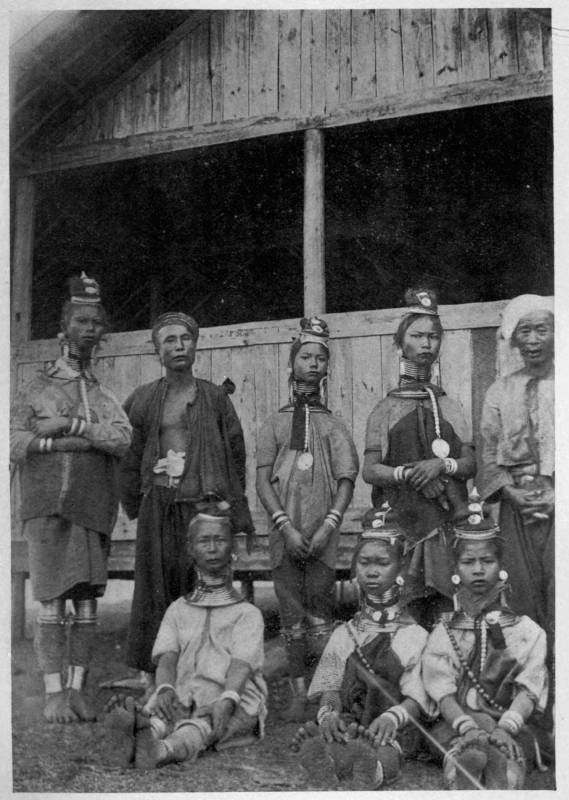

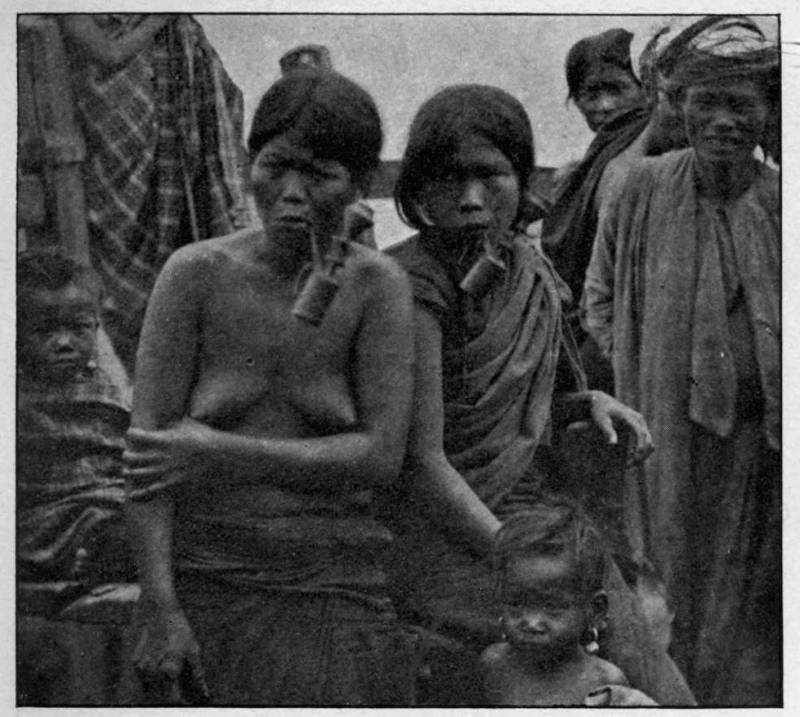

| PADAUNG LADIES—SHAN STATES | 154 |

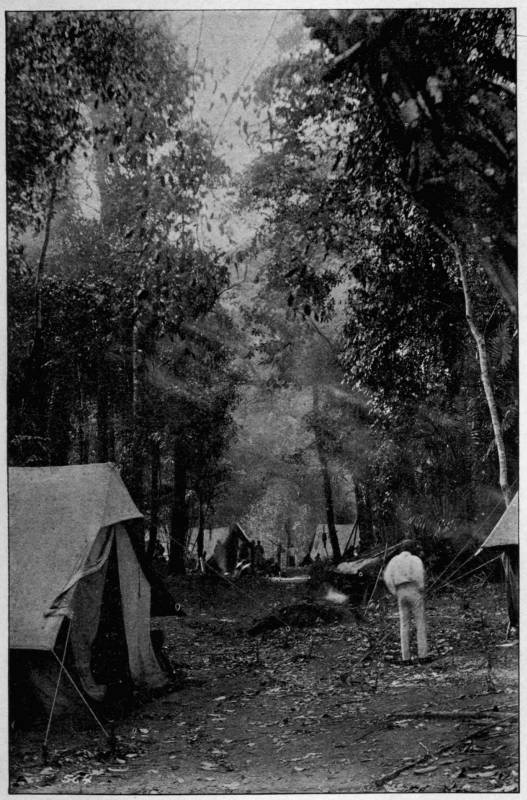

| A JUNGLE CAMP IN THE SHAN STATES | 166 |

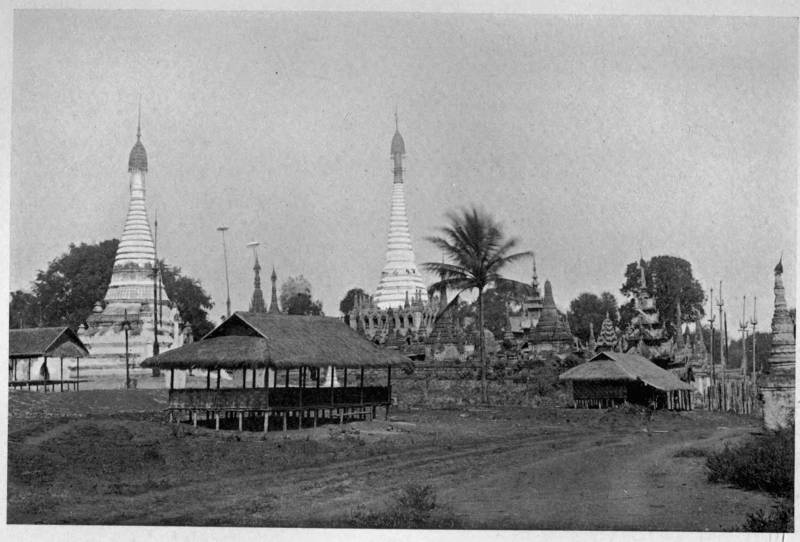

| PAGODAS AT MANG KAO-SHAN STATES | 180 |

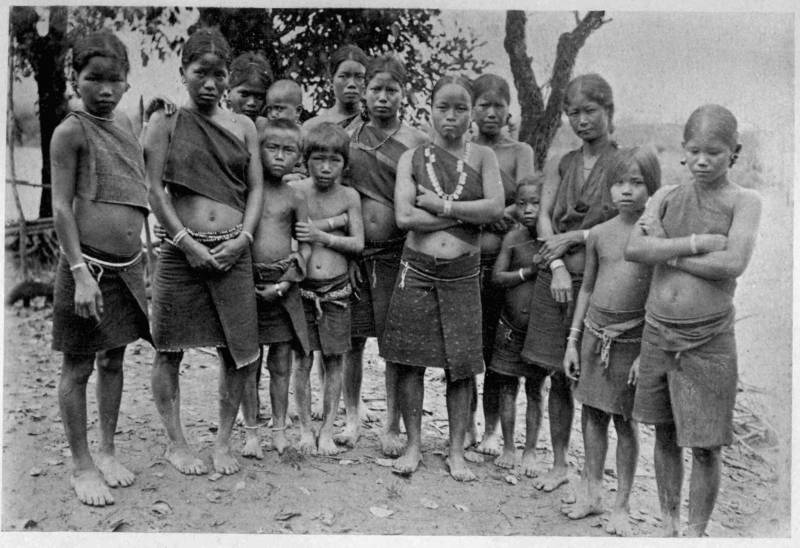

| GROUP OF RED KARENS | 190 |

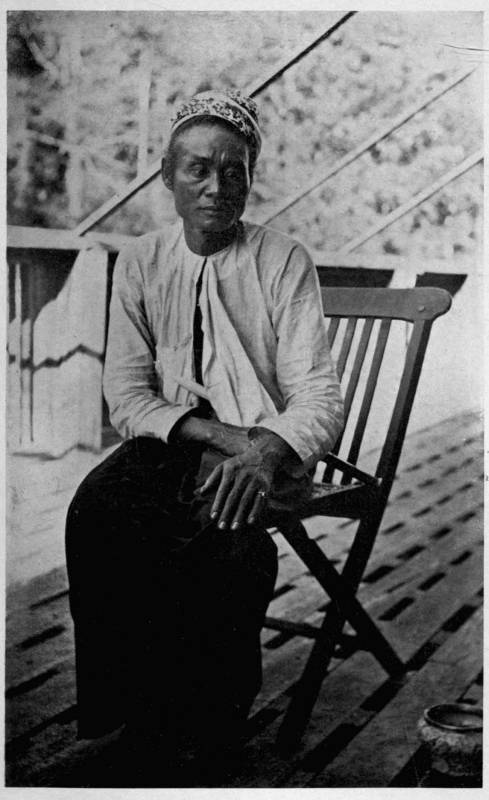

| SAWLAWI—SAWBWA GANTARAWADI. (RED KARENS) | 202 |

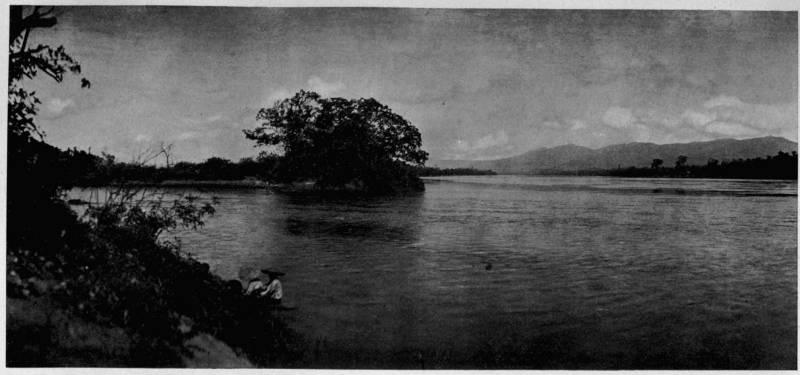

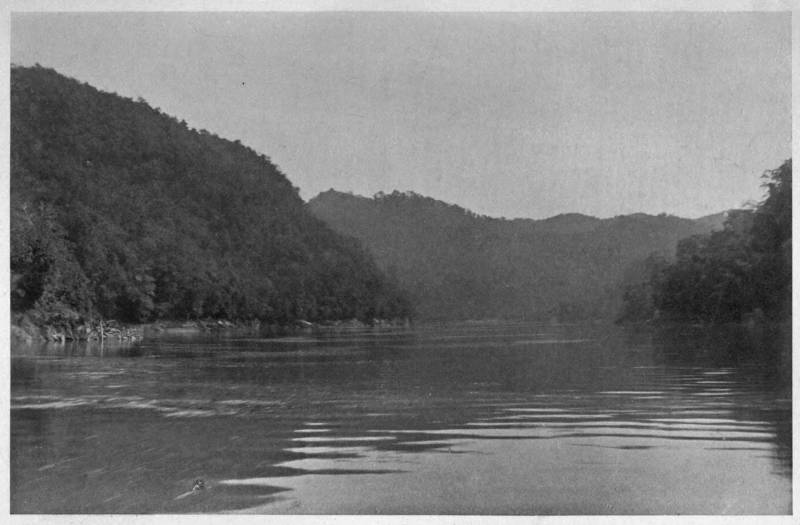

| THE EASTERNMOST POINT OF THE BRITISH-INDIAN EMPIRE—REACH | |

| OF THE ME KHONG, WHERE OUR BOUNDARY | |

| MARCHES WITH FRENCH INDO-CHINA | 212 |

| KACHIN WOMEN AND CHILDREN | 244 |

| [xii] | |

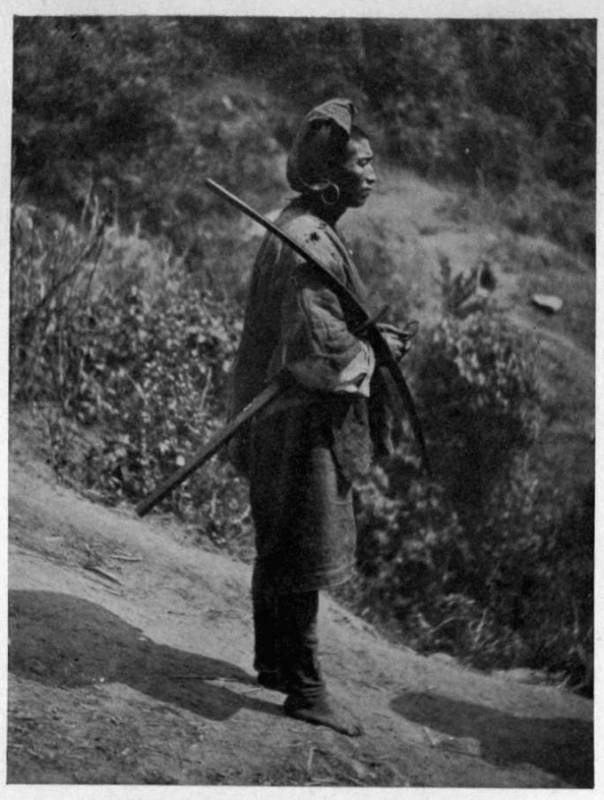

| YAWGIN WITH CROSS-BOW (MOUNTAINS NORTH OF MYIT KYINA) | 250 |

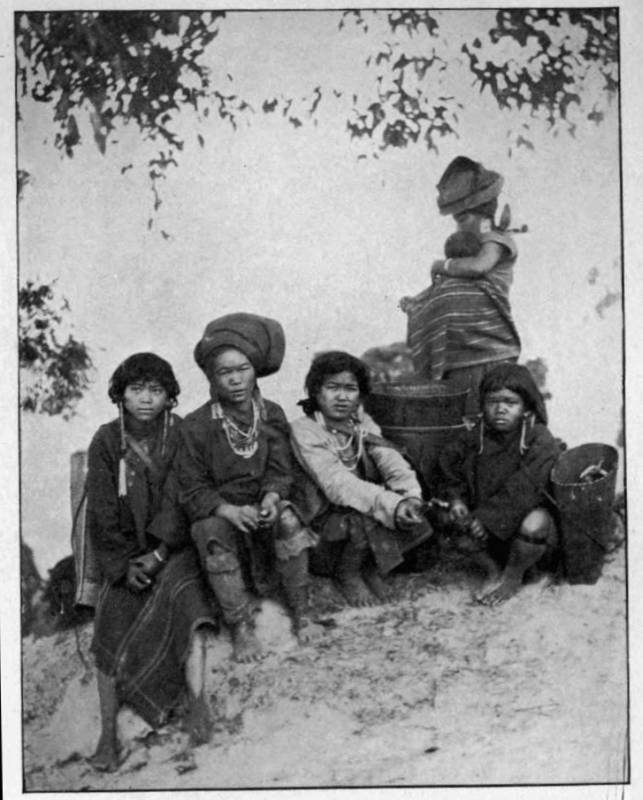

| KACHIN WOMEN (NORTHERN IRRAWADDY) | 250 |

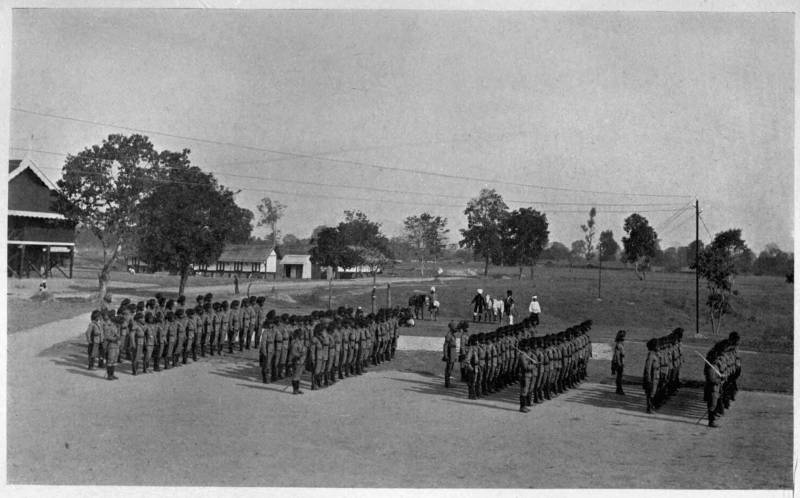

| BHAMO BATTALION DRAWN UP FOR INSPECTION | 252 |

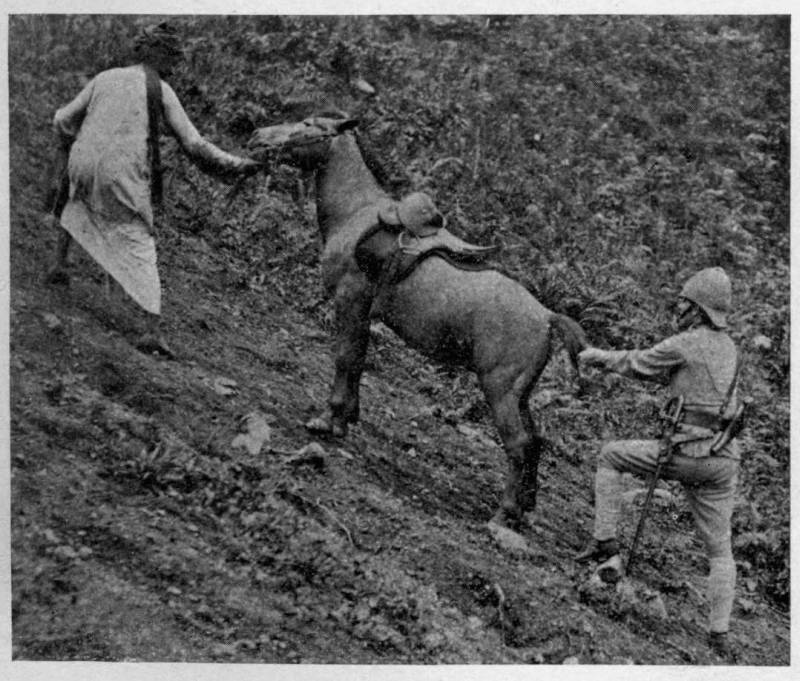

| GETTING A DHOOLIE UP AN AWKWARD BIT | 268 |

| CLIMBING UP THE STEEP CHIN HILLS (CHIN CAMPAIGN) | 268 |

| BARGAINING WITH HAKA CHINS | 276 |

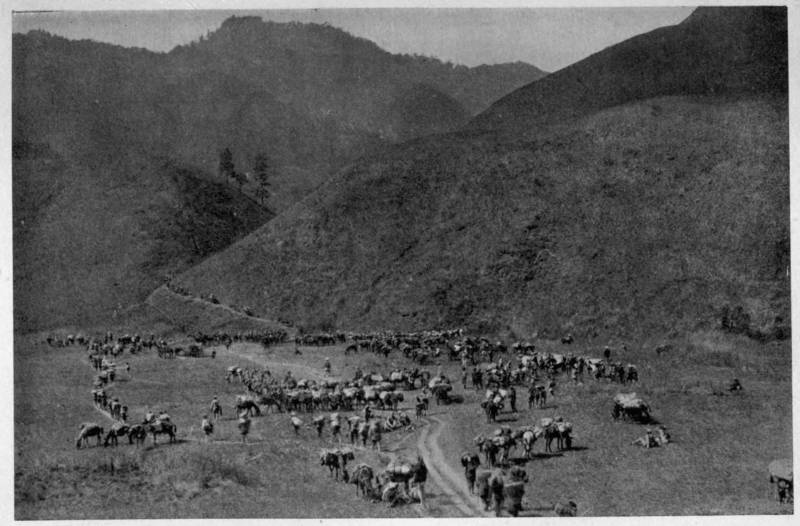

| MARCHING INTO THE KLANG KLANG COUNTRY (CHIN-LUSHAI | |

| CAMPAIGN) | 282 |

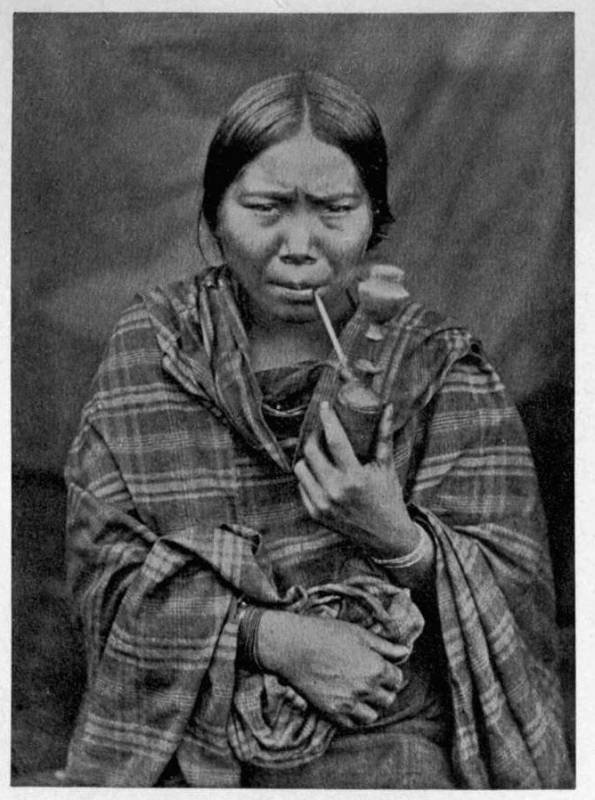

| HAKA SLAVE-WOMAN SMOKING A PIPE | 284 |

| HAKA BRAVES | 284 |

| ON THE CHIN HILLS—ARRANGING PLAN OF ATTACK (CHIN-LUSHAI | |

| CAMPAIGN) | 288 |

| HAKA CHINS | 292 |

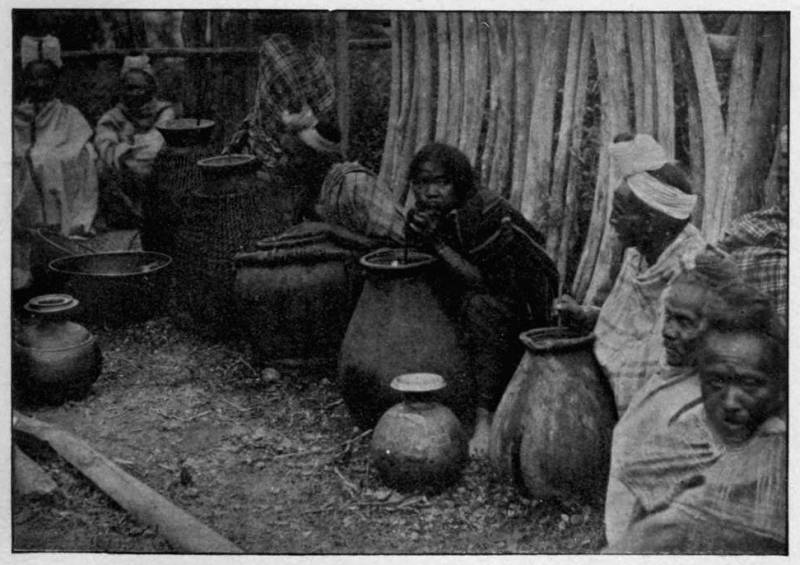

| A CHIN "ZU" DRINK | 292 |

| IN THE SECOND DEFILE OF THE IRRAWADDY BELOW BHAMO | 304 |

| BURMESE LADIES MAKING A CALL | 324 |

| MAPS | |

| MAP OF SHAN STATES | 133 |

| MAP OF TRANS-SALWEEN | 209 |

| MAP OF BHAMO MONGMIT | 234 |

| MAP OF CHIN HILLS, ETC. | 253 |

| MAP OF KACHIN HILLS, BHAMO, KATHA | 303 |

On the 20th of December, 1852, Lord Dalhousie issued a proclamation annexing the province of Pegu to the British Dominions. "The Governor-General in Council," he said, "having exacted the reparation he deems sufficient, desires no further conquest in Burma and is willing that hostilities should cease.

"But if the King of Ava shall fail to renew his former relations with the British Government, and if he shall recklessly seek to dispute its quiet possession of the province it has now declared to be its own, the Governor-General in Council will again put forth the power he holds and will visit with full retribution aggressions, which, if they be persisted in, must of necessity lead to the total subversion of the Burman State and to the ruin and exile of the King and his race."

In 1885 the fulfilment of this menace—prophecy it might be called—was brought about by the contumacy of the Government of Ava. The Burman State was "totally subverted." Its territories were added to the British Empire. The King and his race were "ruined and exiled."

At the end of November, 1885, the British commander was in full possession of Mandalay, the capital. Our forces had made a procession up the great river, which is the main artery of the country, almost unopposed. Such opposition as there had been was childish in its feebleness and want of skill and purpose. Fortunately for us the King and his[2] ministers prided themselves on their voluntary army system. King Thebaw was not going to compel his subjects to defend their country. They were told to go about their daily tasks without fear or carefulness. They might sleep in their beds. He would see to it that the foreign barbarians were driven into the sea whence they had come. Unfortunately the soldiers to whom he trusted were insufficiently trained, badly armed and equipped. He had intended, perhaps, to remedy all this and to train his troops for six months before the fighting began.

His enemy, however, was unreasonably hasty and had an abundance of fast steamers for transporting the invading force. Before the training could begin or the arms be provided or the officers instructed, the invaders were before Ava, where the bulk of the defending army had been collected, and a few miles from the capital. The King's government was as helpless as it had been arrogant and pretentious. Ministers of State were sent down in hot haste with messages of submission and surrender.

The army, however, took a different view of the case. They refused to obey the order to surrender which had come from Mandalay. Before General Prendergast could land his men they dispersed over the country in every direction with their arms, and as the British force had no cavalry to pursue them, they got away to a man. At first under various leaders, few of whom showed any military talent, they waged a guerilla warfare against the invaders; and afterwards, when their larger divisions had been defeated and broken up, they succeeded in creating a state of anarchy and brigandage ruinous to the peasantry and infinitely harassing to the British.

On the 29th of November Mandalay was occupied and the King a prisoner on his way down the river to Rangoon. The waterway from Mandalay to the sea was under our control. A few of the principal places on the banks of the river had been held by small garrisons as the expedition came up, and the ultimate subjugation of the Burman people was assured. The trouble, however, was to come.

To a loosely organized nation like the Burmese, the occupation of the capital and the removal of the King meant nothing. They were still free to resist and fight. It was[3] to be five years before the last of the large gangs was dispersed, the leaders captured, and peace and security established.

Burma will be, in all likelihood, the last important province to be added to the Indian Empire. Eastward that Empire has been extended as far as our arms can well reach. Its boundaries march with Siam, with the French dominion of Tongking, and on the East and North for a vast distance with China. Our convention with France for the preservation of the territory which remains to Siam and our long friendship with the latter country bars any extension of our borders in that direction. It is improbable that we shall be driven to encroach on Chinese territory; and so far as the French possessions are concerned, a line has been drawn by agreement which neither side will wish to cross.

In all likelihood, therefore, the experience gained in Burma will not be repeated in Asia. Nevertheless it may be worth while to put on record a connected account of the methods by which a country of wide extent, destitute of roads and covered with dense jungle and forest, in which the only rule had become the misrule of brigands and the only order systematic disorder, was transformed in a few years into a quiet and prosperous State.

I cannot hope that the story will be of interest to many, but it may be of some interest and perhaps of use to those who worked with me and to their successors.

From 1852 to 1878 King Mindôn ruled Upper Burma fairly well. He had seized the throne from the hands of his brother Pagan Min, whose life he spared with more humanity than was usual on such occasions. He was, to quote from the Upper Burma Administration Report of 1886, "an enlightened Prince who, while professing no love for the British, recognized the power of the British Government, was always careful to keep on friendly terms with them, and was anxious to introduce into his kingdom, as far as was compatible with the maintenance of his own autocratic power, Western ideas and Western civilization." He was tolerant in religious matters even for a Burmese Buddhist. He protected and even encouraged the Christian missions in Upper Burma, and for Dr. Marks, the[4] representative of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Mandalay he built a handsome teak church and a good clergy-house, giving a tinge of contempt to his generosity by putting them down by the Burmese burial-ground. The contempt was not for the religion but for the foreign barbarians who professed it.

His measures for encouraging trade and increasing and ordering the revenues were good, and the country prospered under him. In Burma there are no hereditary leaders of the people. There is no hereditary aristocracy outside the royal family, and their descendants rapidly merge into the people. There was no law or binding custom determining the descent of the crown within the family. Every one with royal blood, however little, in his veins was a potential pretender. Whenever the crown demised the succession was settled by intrigue or violence, and possible aspirants were removed by the prince who had obtained the prize. There was no other way of securing its peaceful enjoyment.

Under the King was the Hlutdaw, or great Council of State, composed of the Chief Ministers, who were appointed by the King from the courtiers who had the good fortune to be known to him or had helped him to the throne. To each of these was assigned a province of the empire, which he governed through a deputy.

The immediate power was vested in the deputy, who resided in the province and remitted to the Minister as much as he could collect over and above the amount due to the crown and, it need hardly be said, necessary for his own needs. The provinces were divided into townships, which were ruled by officials appointed by the governors, no doubt with regard to local influence and claims, and with a general inclination to keep the office in a family.

The really stable part of the administration on which everything rested was the village, the headship of which was by custom hereditary, but not necessarily in the direct line.

As there was little central control, it may be supposed that under a system of this kind the people were pillaged, and doubtless they were to some extent. But the deputy-governor on the spot had no organized police or militia to[5] support him. If he wanted to use force he had to pay for it, and if he drove his province to the point of rebellion he was unlikely to profit by it.

The amount of revenue was fixed at Mandalay with reference to a rough estimate of what the province could pay, and that was divided amongst the townships and again amongst the villages. The headman of each village, assisted by a committee or Punchayet, as it would be called in India, settled the sum due from each householder, and this was as a rule honestly and fairly done. It was not a bad system on the whole, and it was in its incidence probably as just as local taxation in Great Britain, which I admit is somewhat faint praise.

As to the administration of justice between man and man and the security of life and property, there was no doubt little refinement of law and not always impartiality in the judges. The majority of civil cases in a society like Burma, where there are few rich men and no great landowners, must be trivial, and in Burma disputes were settled by arbitration or by the village headmen, who could rarely set at nought the opinion of their fellow-villagers.

In a country which is under-populated and contains vast areas of land fit for cultivation unoccupied and free to all, migration is a great check on oppression. Life is simple in Burma. The climate for the most of the year makes a roof unnecessary; flitting is easy. Every man is his own carpenter. He has put together his house of bamboo and planks cut by his own hands. He knows how to take it down. He has not to send for contractors or furniture vans. There are the carts and the plough cattle in his sheds. He has talked things over with his wife, who is a capable and sensible woman.

One morning they get up, and instead of going to his fields or his fishing or whatever it may be, he takes his tools, and before sunset, his wife helping, the house is down and, with the simple household goods, is in the cart. The children find a place in it, or if they are old enough they run along with the mother. If the local magistrate is so blind to his own interests as to oppress his people, there is another wiser man a few score leagues away who is ready to welcome them. For what is the good of land without[6] men to live on it? Is not the King's revenue assessed at so much to the house? But suppose the worst comes to the worst and the man in power is a fiend, and neither property nor life nor honour is safe from him, even then there is the great forest, in which life, though hard, is a real pleasure to a man; and, given a good leader, the oppressed may soon change places with his oppressor.

We are too ready to imagine that life under such a King as Mindôn or even as Thebaw must be unbearable. We fancy them armed with all the organization of the Inland Revenue Department and supported by a force like our constabulary. Fortunately they were not. No system of extortion yet devised by the most ruthless and greedy tyrant is at all comparable in its efficacy to the scientific methods of a modern revenue officer. The world will see to what a perfection of completeness the arts of oppression and squeezing can be carried when the power of modern European organization is in the hands of a socialist government.

It need not be supposed, therefore, that under King Mindôn life in Upper Burma was bad, and it must be remembered that since 1852 escape to British Burma, although forbidden, was not impossible.

Under Thebaw things were different. Mindôn was on the whole well-intentioned, and had kept the power in his own hands. Thebaw was weak and incompetent, and the Ministers who had most influence with him were the worst men. With his barbarities, old-fashioned rather than unexampled, and perhaps not much worse than the measures of precaution usually taken in Burma after the succession of a new king, or with the causes of the war which led to his deposition, the present narrative is not concerned. It is desired to give as clear an idea as possible of the state of Upper Burma when we were called upon to administer the country.

The rapacity and greed of the Court, where the Queen Supayalat was the ruling spirit, set the example to the whole hierarchy of officials. The result was a state of extreme disorder throughout the whole kingdom. The demands made on the people for money became excessive and intolerable. Men left their villages and took to the jungle. Bands of armed brigands, some of considerable strength under active leaders, sprang up everywhere. Formed in the first instance as a protest and defence against extortion, they soon began to live on the country and to terrorize the peasantry. After a time, brigands and Ministers, finding themselves working for a common object, formed an unholy alliance for loot. The leaders of the bands came to an understanding with the more powerful officials, who in turn leant upon them for support.

Under such conditions it was not wonderful that the sudden seizure of the capital and the summary removal of the King should have completed the dissolution of society, already far advanced. The British Government, if it had decided to annex Upper Burma, might by a more leisurely occupation, not only with a larger military force, but with a complete staff of civil administrators, have saved the people from some years of anarchy and great suffering. But that is not our way, and under modern political conditions in England is impossible.

The country was taken and its government destroyed before we had decided what we should do with it, or considered the effect on the people.

The King's rule ended on the 29th of November, 1885. On the 1st of January, 1886, the Viceroy's proclamation included Upper Burma in Her Majesty's dominions. The administration of the country was temporarily provided for by allowing the Hlutdaw, or great Council of State, to continue in power, discharging all its functions as usual, but under the guidance of Colonel (afterwards Sir E. B.) Sladen, who was attached as Political officer to General Prendergast's staff. All Civil officers, British and Burmese, were placed under the Hlutdaw's orders, and the King's Burmese officials throughout the country were instructed to go on with the regular performance of their duties as if nothing had occurred. Some arrangement had to be made, and probably this was the best possible. The best was bad.

On the 15th of December the Chief Commissioner, Sir Charles Bernard, arrived at Mandalay from Rangoon. On his way up the river he had visited Minhla, Pagan and Myingyan, where Civil officers, supported by small garrisons,[8] had been placed by General Prendergast. He decided that these three districts should be removed from the jurisdiction of the Hlutdaw and controlled directly by himself. Mandalay town and district were similarly treated. A British officer was appointed to govern them, under the immediate orders of Colonel Sladen, who was responsible to the Chief Commissioner.

All this must have confused the minds of the people and prevented those who were ready to submit to the British power from coming forward. Fortunately this period of hesitation was short. From the 26th of February, 1886, Upper Burma became a province of British India.

When the Chief Commissioner, who had gone down to Rangoon with the Viceroy, returned to Mandalay, the Hlutdaw was finally dissolved and Sir Charles Bernard took the government into his own hands. A few of the Burmese Ministers were retained as advisers. At first they were of some use as knowing the facts and the ways of the King's administration. Very soon they became superfluous.

It must not be supposed that no steps had been taken towards the construction of an administration during the first two months of the year. Anticipating the decision of Her Majesty's Government, Sir Charles Bernard had applied his signal energy to this work, and before the end of February the Viceroy had laid his rough proposals before the Secretary of State. As soon as Upper Burma was incorporated with British India the scheme of government already drafted came into force.

The country was mapped out into fourteen districts, corresponding as closely as possible to the existing provinces under the King, namely:—

| Mandalay | Minbu | Pagan |

| Katha | Bhamo | Ningyan, afterwards |

| Ava | Shwèbo | called Pyinmana |

| Chindwin | Kyauksè | Ye-w |

| Myingyan | Sagaing | Yamèthin |

and after a time three more were added: Taungdwingyi, Meiktila, and the Ruby Mines. The boundaries were necessarily left vague at first until more accurate knowledge of the country enabled them to be defined. At first there[9] were no maps whatever. The greater part of the country had not been occupied nor even visited by us.

To each district was appointed an officer of the Burma Commission under the style of Deputy Commissioner, with a British police officer to assist him and such armed force of police as could be assigned to him. His first duty was to get in touch with the local officials and to induce those capable and willing to serve us to retain or take office under our Government.

Having firmly established his authority at headquarters, he was to work outwards in a widening circle, placing police posts and introducing settled administration as opportunity offered. He was, however, to consider it his primary object to attack and destroy the robber bands and to protect the loyal villages from their violence. There were few districts in which the guerilla leaders were not active. Their vengeance on every Burman who attempted to assist the British was swift and unmerciful. As it was impossible at first and for some time to afford adequate protection, villages which aided and sheltered the enemy were treated with consideration. The despatch of flying columns moving through a part of the country and returning quickly to headquarters was discouraged. There was a tendency in the beginning of the business to follow this practice, which was mischievous. If the people were friendly and helped the troops, they were certain to suffer when the column retired. If they were hostile, a hasty visit had little effect on them. They looked on the retirement as a retreat and became more bitter than before.

Upper Burma was incorporated with British India on the 26th of February. Thereupon the elaborate Statute law of India, including the Civil and Criminal Codes, came into force, a body of law which implies the existence of a hierarchy of educated and trained officials, with police and gaols and all the machinery of organized administration. But there were none of these things in Upper Burma, which was, in fact, an enemy's country, still frankly hostile to us. This difficulty had been foreseen, and the proper remedy suggested in Lord Dufferin's minute (dated at Mandalay on the 17th of February, 1886) in which he proposed to annex the country.

The Acts for the Government of India give to the Secretary of State the power of constituting any province or part of a province an excepted or scheduled district, and thereupon the Governor of the province may draw up regulations for the peace and good government of the district, which, when approved by the Governor-General in Council, have the full force of law.[1]

This machinery is put in force by a resolution of the Secretary of State in Council, and at the Viceroy's instance a resolution for this purpose was made, with effect from and after the 1st of March, 1886. It applied to all Upper Burma except the Shan States.

Sir Charles Bernard was ready to take advantage of the powers given to him. Early in March he published an admirable rough code of instructions, sufficiently elastic to meet the varying conditions, and at the same time sufficiently definite to prevent anything like injustice or oppression. The summary given in Section 10 of the Upper Burma Administration Report for 1886 shows their nature.

"By these instructions each district was placed in charge of a Civil officer, who was invested with the full powers of a Deputy Commissioner, and in criminal matters with power to try as a magistrate any case and to pass any sentence. The Deputy Commissioner was also invested with full power to revise the proceedings of any subordinate magistrate or official and to pass any order except an order enhancing a sentence. In criminal matters the courts were to be guided as far as possible by the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Penal Code, and the Evidence Act (i.e., the Indian Codes). But dacoity or robbery was made punishable with death, though magistrates were instructed to pass capital sentences only in very heinous cases. In order to provide a safeguard against undue severity in the infliction of punishments, it was ordered that no capital sentence should be carried out except after confirmation by the Chief Commissioner. No regular appeals were allowed from any decision; but it was open for any one who felt aggrieved by the decision of a subordinate officer to move the Deputy Commissioner to revise the order, and for any one who demurred to an order passed by a Deputy Commissioner to bring the matter to the notice of the Chief Commissioner.

"In revenue matters the customs of the country were as far as possible to be observed, save that no monopolies (except that of precious stones) were allowed and no customs or transport duties were levied. As regards excise administration, in accordance with the custom of the country the sale of opium and of intoxicating liquors to Burmans was prohibited. But a limited number of licences were issued for the sale of liquors to persons not of Burmese race, and the Chinese were specially exempted from the restrictions imposed on the traffic in opium."

Thus in four months after annexation the country had been parcelled into seventeen districts, each under the charge of a Deputy Commissioner, who was guided by the provisional instructions and worked at first directly under the Chief Commissioner. It was thought (vide Lord Dufferin's minute of February 17, 1886) that the province could be worked, in the beginning, without any authority such as Divisional Commissioners or Sessions Judges interposed between the Chief Commissioner and the district officers. "I would adopt, as I have already said," wrote Lord Dufferin, "the simplest and cheapest system of administration open to us. There will be in each district or circle one British Civil officer and one police officer. The Civil officer will work through the indigenous agency of the country, Myo-ôks (governors of towns), Thugyis (headmen of villages) and others, confining his efforts in the first instance to the restoration of order, the protection of life and property, and the assessment and collection of the ordinary revenue.... But most of the unimportant criminal work and nearly all the civil suits must be disposed of by the native officials, subject to the check and control of the district officer."

The area of the province, excluding the Shan States, which were left to the care of their own chiefs, was nearly one hundred thousand square miles. It was divided into seventeen districts. There were no roads in the interior, much of which was difficult country. The Irrawaddy, it is true,[12] formed a splendid line of communication from north to south. But the river was not connected with the districts east or west of it by anything better than an ordinary village cart-track, with numerous streams and rivers, most of them unbridged. The Eastern districts between the Sittang and the Irrawaddy were especially inaccessible. Under such circumstances it was impossible for any man to discharge the duties imposed on the Chief Commissioner, even if all his subordinates had been endowed with ripe wisdom and experience. Only a man of the heroic energy and devotion of Sir Charles Bernard could have conceived it possible. Moreover, the Chief Commissioner was to be responsible for all death sentences, and was to be the final Court of Revision for the province; while the lower province also remained in his charge, and although he was relieved of the routine work of Lower Burma, the responsibility still rested on him, and was by no means nominal. It was not business.

The difficulty soon began to be felt. In June a Commissioner was appointed for the Eastern Division, Mr. St. G. Tucker, from the Punjab. In August and September three more commissionerships were constituted, to one of which, the Northern, was appointed Mr. Burgess (the late Mr. G. D. Burgess), of the Burma Commission; to the Central Division, Mr. F. W. Fryer (now Sir Frederick Fryer), from the Punjab; and Mr. J. D. La Touche (now Sir James La Touche) from the North-Western Provinces to the Southern Division. The Chief Commissioner delegated to them, in their respective divisions, the general control of the district officers and the revision of their judicial proceedings, including the duty of confirming sentences of death.

The administrative divisions of the province, excluding the Shan States, then stood as follows:—

| 1. The Northern Division | Bhamo |

| Katha | |

| Shwèbo | |

| Ruby Mines | |

| Mandalay | |

| [13] | |

| 2. The Central Division | Sagaing |

| Kyauksè | |

| Yeu | |

| Chindwin | |

| Ava | |

| 3. The Eastern Division | Meiktila |

| Yamèthin | |

| Ningyan (afterwards called Pyinmana) | |

| 4. The Southern Division | Myingyan |

| Pagan | |

| Minbu | |

| Taungdwingyi |

This organization enabled the Chief Commissioner to attend to his own work and brought the task of governing the whole of Burma within the powers of an energetic man. It enabled him to give sufficient time to the organization of the revenue and of the police and to the exercise of that control without which there could be no united action. The attempt to govern without an authority intervening between the executive officers in the districts and the head of the province was due to a desire for economy, and to the belief that in this way there would be closer connection and easier communication between the Chief Commissioner and the executive officers. In fact, the contrary was the result, and in all such cases must be.

The framework of a civil administration had now been formed. It remained to give the district officers such armed support as would enable them to govern their charges.

In the autumn of 1886 the country generally was far from being under our control. It had been supposed that our coming was welcome to the people and that "the prospects of the substitution of a strong and orderly government for the incompetent and cruel tyranny of their former ruler" was by the people generally regarded with pleasure. (See Lord Dufferin's minute of February 17, 1886.) But[14] by July it had become evident that a considerable minority of the population, to say the least, did not want us, and that until we proved our strength it was idle to expect active help even from our friends.

The total military force hitherto employed in Upper Burma had been about fourteen thousand men. There was not anywhere in the whole country a well-armed or organized body of the enemy. A few hundred British troops could have marched from north to south or from east to west without meeting with very serious opposition or suffering much loss. Small flying columns could be moved through the country and might find no enemy, and might even gather from the demeanour of the people that they were welcome. When the soldiers passed on, the power of the British Government went with them, and the villagers fell back under the rule of the guerilla leaders and their gangs. At first there may have been some faint tinge of patriotism in the motives which drove the leaders and members of these bands to take the field. Very soon they became mere brigands, living on the villagers and taking whatever they wanted, including their women.

"These bands are freebooters," wrote Sir George White[2] (to the Quartermaster-General in India, July 17, 1886), "pillaging wherever they go, but usually reserving the refinement of their cruelty for those who have taken office under us or part with us. Flying columns arrive too late to save the village. The villagers, having cause to recognize that we are too far off to protect them, lose confidence in our power and throw in their lot with the insurgents. They make terms with the leaders and baffle pursuit of those leaders by roundabout guidance or systematic silence. In a country itself one vast military obstacle, the seizure of the leaders of the rebellion, though of paramount importance, thus becomes a source of greatest difficulty."

The experience of the first half of 1886 had brought home to the Government of India as well as to the military officers in the field that the resistance was more widespread and more obstinate than any one had foreseen. Sir George White considered that "the most effective plan of establishing our rule, and at the same time protecting and gaining touch of the villages, is a close occupation of the disturbed districts by military posts" (ibid.). Under the circumstances, this was the best course to adopt, provided that the posts were strong enough to patrol the country and to crush every attempt at rising. The people might be held down in this way, but not governed. Something more was necessary. The difficulties were to be overcome rather by the vigorous administration of civil government than by the employment of military detachments scattered over the country. A sufficient force of armed police at the disposal of the civil officers was therefore a necessity.

It had been foreseen from the first by Sir Charles Bernard and the Government of India, although the strength of the force necessary to achieve success was much under-estimated. In February, 1886, two military police levies, each of five hundred and sixty-one men, were raised from the Indian army. Of these one was sent to the Chindwin district and one to Mandalay. At the same time the recruitment of two thousand two hundred men in Northern India for a military police force was ordered. These men were untrained and came over in batches as they were raised. They were trained and disciplined at Mandalay and other convenient places, and were distributed to the districts when they were sufficiently formed. Thus besides the soldiers the Chief Commissioner had about 3,300 men at his disposal.

As the year went on and the magnitude of the undertaking began to be understood, the need of a much larger force was admitted. Two more levies were sanctioned. One from Northern India was raised without difficulty, and was posted to the railway line from Toungoo to Mandalay, which had been tardily sanctioned by the Secretary of State in November, 1886, and was at once put in hand. The other, a Gurkha battalion for use in the Northern frontier subdivision of Mogaung, was more difficult to recruit. At the end of the year two companies had arrived, and after being trained at Mandalay had gone on to Bhamo. By this time forty-six posts were held by the military police. The hunger for men, however, so far from being satisfied, continued to grow. After reviewing the position[16] in November (1886) Sir Charles Bernard decided to ask the Government of India for sixteen thousand men, including those already sanctioned, nine thousand to be recruited in India and seven thousand in Burma.

It was proposed that ultimately half of this force should be Indians and half local men. They were all to be engaged for three years, and were to be drilled and disciplined, and divided into battalions, one for each district. Each battalion was to contain fixed proportions of Indians and local men, "under the command of a military officer for the purpose of training and discipline and under the orders of the local police officers for ordinary police work." At this time it was believed that Burmans, Shans, Karens and Kachins could by training and discipline become a valuable element in a military police force, and the experiment was made at Mandalay. This was the beginning of the Burma military police force, which contributed so pre-eminently to the subjugation and pacification of the province. The attempt to raise any part of it locally was, however, very quickly abandoned, and it was recruited, with the exception of a few companies of Karens, entirely from Indians.

But to return to the middle of 1886. Sir George White, in writing to Army Headquarters, urged the necessity of reinforcements. The fighting had, it is true, been trivial and deaths in action or by wounds had amounted to six officers and fifty-six men only. Disease, however, had been busy. Exposure and fatigue in a semi-tropical climate, the want of fresh food in a country which gave little but rice and salt fish, was gradually reducing the strength and numbers of the force. One officer and two hundred and sixty-nine men had died of disease and thirty-nine officers and nine hundred and twenty men had been invalided between November, 1885, and July, 1886.

There were few large bodies of the enemy in the field—few at any rate who would wait to meet an attack. It was only by a close occupation of the disturbed districts by military posts that progress could be made. The Major-General Commanding did not shrink from this measure, although it used up his army. Fourteen thousand men looks on paper a formidable force, but more men, more[17] mounted infantry, and especially more cavalry were necessary.

It had been a tradition at Army Headquarters, handed down probably from the first and second Burmese Wars, that cavalry was useless in Burma. The experience of 1885-6 proved it to be the most effective arm. It was essential to catch the "Bos," or captains of the guerilla bands, who gave life and spirit to the whole movement. Short compact men, nearly always well mounted, with a modern jockey seat, they were the first as a rule to run away. The mounted infantry man, British or Indian, a stone or two heavier, and weighted with rifle, ammunition, and accoutrements, on an underbred twelve-hand pony, had no chance of riding down a "Bo." But the trooper inspired the enemy with terror.

"In a land where only ponies are bred the cavalry horses seem monsters to the people, and the long reach and short shrift of the lance paralyse them with fear," wrote Sir George White, and asked that as soon as the rains had ceased "three more regiments of cavalry, complete in establishments," should be added to the Upper Burma Field Force.

The proposal was accepted by the Commander-in-Chief in India, Sir Frederick Roberts, and approved by the Government of India. It may be said here once for all that the Government of India throughout the whole of this business were ready to give the local authorities, civil and military, everything that was found necessary for the speedy completion of the work in hand, the difficulties of which they appreciated, as far as any one not on the spot could.

"It is proposed," they wrote to Lord Cross (August 13, 1886), "to reinforce the Upper Burma Field Force by three regiments of native cavalry and to relieve all or nearly all the corps and batteries which were despatched to Burma in October last. The troops to be relieved will be kept four or five months longer, so that, including those sent in relief, the force will be very considerable and should suffice to complete rapidly and finally the pacification and settlement of the whole country."

In consequence of the increased strength of the field[18] force the Government of India directed Lieutenant-General Sir Herbert Macpherson, Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army, to transfer his headquarters to Burma and remain there until the conclusion of the operations. Unfortunately, Sir Herbert died shortly after reaching Burma. The Commander-in-Chief in India, Sir Frederick Roberts, then took charge of the business and landed in Rangoon in November.

It was evident that Sir George White had not exaggerated the difficulties of the work. After taking stock of the position, Roberts asked for five more regiments to be sent from India. During the cold or, as it should be called in Burma, the dry season following, much was done to gain control of the country, under the personal supervision of the Commander-in-Chief. Especially in the Eastern Division, where large bands of men under various pretenders had been most troublesome, the stern energy of General Lockhart produced a rapid and wholesome change. When Sir Frederick returned to India in February, 1887, the subjugation of Upper Burma had been accomplished and the way was cleared for the civil administration. But four years of constant patient work were needed before the country was pacified and the peasant who wished to live a life of honest industry could accomplish his desire.

[1] "The Government of India," by Sir Courtenay Ilbert, chap. i. p. 105. Second edition.

[2] Major-General, commanding the Burma Field Force, now Field-Marshal Sir George White, V.C., G.C.B., &c.

My first acquaintance with Burma was made in the early part of 1883. I was then a member of the Legislative Council of India. Mr. Charles Bernard, who was Chief Commissioner of British Burma, had asked for a year's leave, and Lord Ripon selected me to take his place. During that year, 1883-4, I went over Lower Burma—British Burma as it was then called—and learnt the methods of the administration and became acquainted with the officers in the commission and the nature of the country and its people.

There was at that time very little communication between the Court of Ava and the Chief Commissioner, who represented the Governor-General in Council. The embassy which the King had sent to Simla with the ostensible purpose of making a new treaty had been suddenly recalled, notwithstanding, and perhaps in some degree because of, the very honourable and hospitable manner in which Lord Ripon had received it. The King was already negotiating a treaty with France, and in 1883, before the mission despatched for this purpose to Europe had left Mandalay, it was believed to have been drafted. But when I surrendered the office to Sir Charles Bernard on his return from leave in February, 1884, there was no thought of war in the near future.

From Rangoon I was transferred to Nagpur, to the post of Chief Commissioner of the Central Provinces. Towards the end of 1885, fever drove me to England on sick leave just as the relations with the King of Burma were broken off and war had become unavoidable. Returning from leave in November, 1886, I found awaiting me at Suez orders posting me to the Public Service Commission,[20] of which the late Sir Charles Aitchison was president. At Bombay I found instructions to proceed at once to Hyderabad in the Deccan, as the Viceroy (Lord Dufferin) desired to see me. At Hyderabad I waited on Lord Dufferin. He told me that Bernard might have to leave, and he wished to know if I would accept the appointment of Chief Commissioner of Burma if he decided to offer it to me. He added that it was in his opinion the post in all India most to be coveted, and that if he was not Viceroy he would choose Burma: an unnecessary stimulus, as ever since leaving that province in 1884 my ambition had been to succeed Bernard. I told the Viceroy that I would go to Burma if it were offered to me.

I was with the Public Service Commission at Lahore, Allahabad, and Jubulpore, and back to Bombay, before I heard anything more about Burma. At the end of January, 1887, we were leaving the Parel Station, Bombay, for Madras, where the next sitting of the Commission was to be, when the train was stopped just as it began to move, and the station-master ran up with a clear-the-line message for me from the Viceroy, desiring me to wait further orders at Bombay. I left the train gladly, as I knew that it meant that I was to go to Burma, and I was delighted to be relieved from the work of the Commission, which was distasteful to me, especially as it appeared from the character of the evidence brought forward, a matter left entirely to the local Government in each province, not likely to lead to beneficial results. On the 3rd of February a telegram dated the 2nd came from the Viceroy, offering me the Chief Commissionership as Bernard's health had broken down, and desiring me to come to Calcutta to consult with the Government.

As soon as I could arrange my affairs I went to Calcutta. The Viceroy received me on the 14th of February. He took me out to the lawn at the side where the great house throws a pleasant shade in the afternoon. There we sat, and Lord Dufferin explained to me how matters stood in Burma, and gave me his instructions on many points and on the general principles which he wished to guide the administration.

The organization of the military police and the material of which the force was to be constituted was one of[21] the chief matters he spoke about. He attached much importance to the enlistment of Burmans, Shans, and Karens, so that the unhealthy posts might be held by acclimatized natives. British officers would have to be posted to command them, and they must be relieved at short intervals. He showed me letters which had passed between him and Bernard about the military police force, to which, as an instrument in the pacification of the province, he attached the first importance. He spoke of the strength of the Commission, and told me to consider it carefully and ask for more men if I thought them necessary. Generally he considered that true economy dictated the expenditure of as much money as was necessary to fit out the new province with offices, roads, buildings, and river steamers, and it was folly, he said, not to give it. Barracks and shelter for troops and police should be vigorously pushed on.

The questions of the Shan States and our relations with China were discussed. As to the Shan States, I represented the manner in which our relations with the feudatory chiefs in the Central Provinces were managed and the saving in cost and responsibility to be gained by leaving them quasi-independent. Lord Dufferin approved of this policy and preferred it to annexation, even in the case of the Wuntho Sawbwa, who had shown an inclination to refuse submission to our Government.

The Viceroy spoke at length and with emphasis regarding our relations with China, which he looked upon as most important. We were face to face, he said, with a very powerful neighbour, who might greatly harass us if she or even her subordinate officials chose to worry us. Two officers of the Chinese Consular Service had been sent to Upper Burma to be at my disposal in dealing with the Chinese in Burma and in conducting relations with the Chinese Government. In the matter of the frontiers of Upper Burma, where they touched China, great care should be exercised. "Feel your way," he said, putting out his hand, "and when you come against anything hard, draw back," advice that was most sound in dealing with the ill-defined boundaries of a conquered province. We wished to hold what our predecessors had held or had been entitled to hold, and we did not desire to leave unoccupied space[22] for others to come in. He told me to think carefully whether there was anything I wanted done and to let him know before I left. I was to see him again.

In a country where one man is as good as another, where there are no landlords, no hereditary aristocracy and no tribal chiefs, the Government, especially a foreign Government, is at a great disadvantage. It is impossible to deal with each individual. The first question is, who is the great man of this village: who has influence, who knows the villagers, their characters and so on? Having found the man, it becomes possible to enter into relations with the village and to treat with them as a whole. In Upper Burma there was a recognized headman in each village who had duties, and powers corresponding to his duties; and in many administrative matters, especially in taxation, the village was dealt with as a whole.

The difficulty in Lower Burma was the absence of such a local authority or unit. The villagers were not held together by any obligation to each other or by subordination to any one on the spot. Each man had his own bit of land which he held directly from the Government. He lived where he pleased, and if he put his house in the same place with other cultivators, it was for the sake of convenience and protection. The villages were grouped for revenue purposes by the British administration under officials who collected the taxes and received a percentage on the amount. Each of these taik Thugyis (headmen of circles), as they were designated, had many villages under him and could not be expected to have local knowledge or personal influence in all of them. He had no powers outside his revenue work. It was open to any one to put up his hut in any village, wherever he could find room. There was no one to say him nay, even if he was a gambler, an opium-eater, or a notorious evildoer living by theft and robbery. There were, it is true, village policemen appointed by law, who were intended to supply the wants of a local authority. But no power was given to them: they were subordinated to the regular civil police and had no status as revenue officials. Consequently they tended to become mere village drudges, although by no means useless and frequently showing both courage and sagacity in police matters.

When I was in Burma in 1883-84 gang-robbery was prevalent, even in the neighbourhood of Rangoon; so much so as to demand close attention from the head of the province. I had observed that in nearly every case where a large gang of dacoits, to use the Indian term, was dominating a district or part of a district they were assisted by sympathisers, who sent them food, supplied them with information, and made it possible for them to live undetected. The codes of Indian Criminal Procedure do not enable a magistrate to touch cases of this sort. If the people are against the Government—and in 1887 they were certainly not minded to help it—the difficulty of detecting and convicting such secret abettors is almost insuperable. At any rate, it was a slow process, and meanwhile violence and disorder flourished and the peasantry became more and more enthralled to the brigands.

It occurred to me that nothing would give the civil magistrate more assistance than the power of summarily removing persons who, while they themselves appeared to be living harmless lives without reproach, were enabling the insurgent or brigand gangs to keep the field.

I explained my views on these matters to the Viceroy. He promised me his support and desired me to embody my ideas in a draft Regulation before I left Calcutta. With the assistance of the Legislative Department the draft was quickly completed, and on my arrival in Burma it was circulated to district officers for their opinions. It was delayed by various formalities and inquiries, and was not finally made law until October, 1887. Founded so far as might be on the system indigenous to the country and in accord with the mind of the people, this law was a great aid to the administration. Writing in October, 1890, I said: "I think that most officers will now admit that the policy of dealing with the people by villages and not by individuals has been a very powerful instrument for suppressing disorder and establishing our authority. It would not have been possible to use this instrument if the village system had no vitality. If we are to rule the country cheaply and efficiently and to keep the people from being robbed and oppressed by the criminal classes, the village system must be maintained in vigour. It cannot thrive or live unless[24] the post of headman is sought after, or at least willingly accepted, by respectable persons." I believe the provisions of the village regulation are still a living force and are brought into action when occasion arises. But the life of the system is the headman, his dignity and his position. This is what the author of "The Soul of a People" wrote in 1898:—

"So each village managed its own affairs untroubled by squire or priest, very little troubled by the State. That within their little means they did it well no one can doubt. They taxed themselves without friction, they built their own monastery schools by voluntary effort, they maintained a very high, a very simple, code of morals entirely of their own initiative.

"All this has passed or is passing. The King has gone to a banishment far across the sea, the Ministers are either banished or powerless for good or evil. It will never rise again, this government of the King which was so bad in all it did and only good in what it left alone. It will never rise again. The people are now part of the British Empire, subjects of the Queen. What may be in store for them in the far future no one can tell; only we may be sure that the past can return no more. And the local government is passing away too. It cannot exist with a strong Government such as ours. For good or for evil, in a few years, it too, will be gone."[3]

This is a prophecy which I believe has not yet been fulfilled, and I hope never will. But to return to the order of events.

I was detained in Calcutta until the 24th of February. Time by no means wasted. I had frequent opportunities of seeing the Members of Council and learning what was going on in each department. Lord Dufferin allowed me to discuss matters with him more than once. On the 19th I attended His Excellency in Council and explained my views, especially regarding the village system. Leaving Calcutta in the British India steamship Rangoon on the 24th, I landed at Rangoon on Sunday the 27th of March. Next day I relieved Sir Charles Bernard and took charge of the Province of Burma.

In order to enable the Chief Commissioner to give more time to the affairs of Upper Burma, a Special Commissioner, Mr. Hodgkinson, had been appointed to take immediate charge of the older province. I found that the Special Commissioner was in fact ruler of the Lower Province, and was so regarded by the public. Nothing which was not of a very extraordinary nature was referred to the Chief Commissioner, whose responsibility, however, remained unimpaired. For example, two or three days after my arrival the Viceroy telegraphed in cipher to the Chief Commissioner about some matters in Lower Burma which had given rise to questions in Parliament, and of which the responsible Chief Commissioner had no cognizance. No more competent and trustworthy man than Mr. Hodgkinson could have been found for the work. Nevertheless the arrangement did not seem to me quite satisfactory.

There were urgent matters requiring to be settled with Mr. Hodgkinson, more especially the Budget of the Province and the organization of the police in Lower Burma, which needed thorough reform. They had earned the reputation of being the worst and the most costly in the world, and during the last eighteen months they had not belied it. It was necessary to form a body of military police for Lower Burma of suitable Indians, trained and disciplined. During the few days I was in Rangoon this and other urgent matters—for example, the arrangements with the Bombay Burma Company about the Upper Burma Forests, the Ruby Mines, the condition of some of the Lower Burma districts, the postings of officers, the distribution of reinforcements of military police just disembarking from the transports, consultations with the General Commanding in Lower Burma as to the measures necessary along and beyond the line of the old frontier within the limits of his command, all these things and much more would have given me plenty of work for many days.

I could only dispose of those matters which required my personal orders and leave the rest to Mr. Hodgkinson. I could not remain in Rangoon. Sir Charles Bernard had a powerful memory. The Upper Burma Secretariat was, as has been said, in Mandalay; when Sir Charles Bernard was in Rangoon, he relied to a great extent on[26] his memory. Letters and telegrams received from Mandalay were dealt with and returned with his orders, no copies for reference being kept. As the Rangoon Secretariat was ignorant of Upper Burma affairs, I found myself completely in the air. I decided therefore to start as soon as possible for Mandalay.

I left Rangoon by rail for Prome on the 9th of March. At Prome a Government steamer, the Sir William Peel, was waiting for me, and I reached Mandalay on the 14th. To a man sailing up the river there were few signs of trouble. The people appeared to be going about their business as usual, and no doubt along the river bank and in the neighbourhood of our posts there was little disorder. But this appearance was deceptive. Just beyond the old frontier the country from the right bank of the Irrawaddy up to the Arakan Yoma was in the hands of insurgents.

On the right bank of the river, forty miles above Thayetmyo, is the Burman fort and town of Minhla, where the first opposition was offered to the British expedition. I found here a small detachment of Indian troops, and in the town, about half a mile off, a police post. I learnt from the British officer commanding the detachment and from the Burman magistrate that for some fifty miles inland, up to the Chin hills on the west, the villages were deserted and the headmen had absconded. This is an unhealthy tract, with much jungle, and broken up into small valleys by the spurs from the Arakan mountains. The noted leader Bo Swè made his lair here and had still to be reckoned with. His story illustrates the difficulties which had to be overcome.

In November, 1885, after taking Minhla, a district was formed by Sir Harry Prendergast consisting of a large tract of country above the British Burma frontier on both sides of the river to Salin, north of Minbu, on the right bank, and including Magwè and Yenangyoung on the left. This district was known at first as Minhla, but afterwards as Minbu, to which the headquarters were moved. Mr. Robert Phayre, of the Indian Civil Service and of the British Burma Commission, was left in charge, supported by a small force.

Mr. Phayre, a relative of that distinguished man, Colonel Sir Arthur Phayre, the first Chief Commissioner of British Burma, was the right man for the work. He began by getting into touch with the native officials, and by the 15th of December all those on the right bank of the river had accepted service under the new Government. Outposts were established, and flying columns dispersed any gatherings of malcontents that were reported. A small body of troops from Thayetmyo, moving about in the west under the Arakan hills, acted in support of Minhla. Revenue began to come in, and at Yenangyoung, the seat of the earth-oil industry, work was being resumed. Everything promised well.

There were two men, however, who had not been or would not be propitiated, Maung Swè and Ôktama. Maung Swè was hereditary headman or Thugyi of Mindat, a village near the old frontier. He had for years been a trouble to the Thayetmyo district of British Burma, harbouring criminals and assisting dacoit gangs to attack our villages, if he did not lead them himself. He had been ordered up to Mandalay by the Burmese Government owing to the strong remonstrances of the Chief Commissioner.

On the outbreak of war Bo[4] Swè was at once sent back to do his utmost against the invaders. So long as there was a force moving about in the west of the district he was unable to do much. When the troops were withdrawn (the deadly climate under the hills compelled their recall), he began active operations.

The second man was named Ôktama, one of the most determined opponents of the British. He had inspired his followers with some of his spirit, whether fanatical or patriotic, and harassed the north of the district about and beyond Minbu. His gang was more than once attacked and dispersed, but came together again. He and Maung Swè worked together and between them dominated the country.

In May, 1886, Maung Swè was attacked and driven back towards the hills. He retired on Ngapè, a strong position thirty miles west of Minbu and commanding the principal pass through the mountains into Arakan. Early in June, 1886, Mr. Phayre, with fifty sepoys of a Bengal infantry regiment and as many military police (Indians), started from Minbu to attack Maung Swè, who was at a place called Padein. The enemy were reinforced during the night by two or three hundred men from Ngapè. The attack was delivered on the 9th of June, and Phayre, who was leading, was shot dead. His men fell back, leaving his body, which was carried off by the Burmans, but was afterwards recovered and buried at Minbu. Three days after this two parties of Ôktama's gang who had taken up positions near Salin were attacked by Captain Dunsford. His force consisted of twenty rifles of the Liverpool Regiment and twenty rifles of the 2nd Bengal Infantry. The Burmans were driven from their ground, but Captain Dunsford was killed and a few of our men wounded.

Reinforcements were sent across the river from Pagan: and Major Gordon, of the 2nd Bengal Infantry, with ninety-five rifles of his own regiment, fifty rifles of the Liverpool Regiment, and two guns 7-1 R.A., attacked Maung Swè in a position near Ngapè. The Burmans fought well, but were forced to retire. Unfortunately the want of mounted men prevented a pursuit. The enemy carried off their killed and wounded. Our loss was eight men killed and twenty-six wounded, including one officer. We then occupied Ngapè in strength, but in July the deadly climate obliged us to withdraw.

Maung Swè returned at once to his lair. By the end of August the whole of the western part of the district was in the hands of the insurgents, rebels, or patriots, according to the side from which they are seen.

Meanwhile Salin had been besieged by Ôktama. He was driven off after three days by Captain Atkinson, who brought up reinforcements to aid the garrison of the post. Captain Atkinson was killed in the action. Thus in a few weeks these two leaders had cost us the lives of three officers.

In the course of the operations undertaken under Sir Frederick Roberts's command in the open season of 1886-87, this country was well searched by parties of troops with mounted infantry. Bo Swè's power was broken, and in March, 1887, he was near the end of his exploits. In the[29] north of the district, the exertions of the troops had made little impression on Ôktama's influence. The peasantry, whether through sympathy or fear, were on his side.

I have troubled the reader with this story because it will help to the understanding of the problem we had before us in every part of Upper Burma. It will explain how districts reported at an early date to be "quite peaceful" or "comparatively settled" were often altogether in the hands of hostile bands. They were reported quiet because we could hear no noise. We were outsiders, as indeed we are, more or less, not only in Burma but in every part of the Indian Empire—less perhaps in Burma than elsewhere.

On the way up the river I had the advantage of meeting Mr. (now Sir James) La Touche, the Commissioner of the Southern Division, Sir Robert Low,[5] commanding at Myingyan, Brigadier-General Anderson, Captain Eyre, the Deputy Commissioner of Pagan district (which then included Pakokku and the Yaw country), and others. At Mandalay I was able to consult with General Sir George White, commanding the field force, with His Excellency Sir Charles Arbuthnot, the Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army, and with the civil officers, namely, the Commissioner of the Northern Division, Mr. Burgess,[6] and Mr. (now Sir Frederick) Fryer, the Commissioner of the Central or Sagaing Division, and their subordinates. No more capable or helpful men could have been found. The Commissioner of the Eastern Division was out of reach for the time. The only way of getting to that country was by road from Mandalay, which would have taken many days. I had to wait until I returned to Rangoon and could go by rail to Toungoo before I made acquaintance with Mr. Henry St. George Tucker, of the Indian Civil Service, a Punjab officer.

[3] "The Soul of a People," pp. 103-4.

[4] Bo means "Captain"; Maung is the ordinary way of addressing a Burman, the equivalent of "Mister."

[5] The late General Sir Robert Cunliffe Low, G.C.B.

[6] The late Mr. G. D. Burgess, C.S.I., Judicial Commissioner, Upper Burma.

I will now give as brief a sketch as may be of the state of Upper Burma when I arrived in Mandalay in March, 1887.

Upper Burma, inclusive of the Shan States, contains in round numbers one hundred and sixty thousand square miles, of which the Shan States cover sixty thousand miles and the Chin hills ten thousand. It may be divided, for the present purpose, into four parts. The first is the great valley of the Irrawaddy, from the mountain ranges north of Mogaung to the northern boundary of the Thayetmyo district; the second is the valley of the Chindwin; the third is the valley of the Sittang, in which lies the Eastern Division, down to the boundary of the Toungoo district; and the fourth is the Shan States. In 1887 the British administration had not yet touched the Chin hills or the Kachins in the mountains which divide Burma from China.

Beginning with the Irrawaddy Valley, Mogaung, the most northerly post of importance, was held by a Burman Myoôk, or township officer, nominally for us. He collected the revenue and spent it—much, no doubt, on his establishment, for which no regular provision had been made. South of Mogaung as far as Bhamo the country was quiet, and no organized gangs were in the field. The Katha district, which comes next below Bhamo, was disturbed on the Wuntho border, and was not much under control.

The Wuntho Sawbwa, a Shan chief exercising independent jurisdiction within his country, had refused our invitation to come in. A strong force under Brigadier-General Cox, with Mr. Burgess, the Commissioner of the Northern Division, had gone to try the methods of peaceful[31] persuasion. The districts south of Katha, namely Shwèbo and Ye-u, were controlled by dacoit gangs under active leaders.

On the left bank of the river the Shan States of Mohlaing and Möngmit were disturbed by the raids of Hkam Leng (vide Chapter XX.). The Ruby Mines district, with its capital, Mogok, was held in force and had remained submissive since its occupation.

South of the ruby mines lies the district of Mandalay, shut in on the north and east by the Shan hills. There was a British force of some thousand men of all arms in Mandalay itself, with several outlying detachments and a strong party in the hills at Pyinulwin,[7] forty miles on the road to Hsipaw. In spite of this force the district was dominated by three or four leaders, who had large followings and acted in concert. They had divided the country between them into definite jurisdictions, which they mutually respected. They collected revenue from the villagers. Disobedience or any attempt to help the British Government met with swift and severe punishment. They professed to be acting under the authority of the Myingun Prince, who was at the time a refugee in Pondicherry, and they were encouraged and helped to combine by a relative of the Prince, known as the Bayingan or Viceroy, who went from one to the other and supplied them with information. The district of Ava, south of Mandalay, was in a similar state. The valleys of the Samôn and Panlaung gave good shelter to the dacoits. Unfortunately several district boundaries and divisions of military commands met in this country, and on that account action was not so prompt as it ought to have been.

Following the river below Ava, the Myingyan and Pagan districts extended to both sides of the river, an inconvenient arrangement inherited from the Burmese Government. The headquarters of these districts, both on the left bank, were held by garrisons of some size, and within striking range the country was controlled.

About forty miles from Pagan town, and as many from the river, is the isolated hill or mountain of Popa. It rises to a height of four thousand five hundred feet, a gigantic cone throwing out numerous spurs. It is wooded thickly almost to the top, and extending for a long distance round it is a tangle of scrub jungle and ravines, an ideal hunting-ground for robbers and the home of cattle-thieves.

South of this was the Taungdwingyi district, extending down to the old border. It was in the hands of a leader named Min Yaung, who was well provided with ponies, and even elephants. The northern spurs of the Pegu Yoma divide this district from the Sittang Valley, and are densely wooded, offering a harbour of refuge to criminals. To this, among other causes, it was due that this district gave more trouble than any other in Upper Burma. It was at that time separated from the river by the Magwè township, which belonged to the Minbu district, and enjoyed comparative peace, owing mainly to the influence of the Burman governor, who had taken service under us and for a time was loyal.

These parts of the Myingyan and Pagan districts, which were on the right bank of the Irrawaddy, were not really under our control or administered by us. The wild tract on the Yaw (vide Chapter XXI., p. 295), which was much left to itself in Burmese times, had not been visited, and was overrun by dacoits.

Southward, still on the right bank, came the Minbu district, where Ôktama and Bo Swè were still powerful, the former in full force.

The difficulties of country and climate which our men had to face in this district were very great. The west of the Minbu district lies up against the range of mountains known as the Arakan Yoma, which run parallel to the sea and shut off the Irrawaddy Valley from the Bay of Bengal. The country below the Yoma is what is known in India as Terai, a waterlogged region reeking with malaria, deadly to those not acclimatized. Many a good soldier, British and Indian, found his grave in the posts occupied in this district, Taingda, Myothit, Ngapè, and Sidoktaya. The dacoit leaders knew the advantage of being able to live where our men could not. Soldiers like Captain Golightly (Colonel R. E. Golightly, D.S.O., late of the 60th Rifles)[33] and his mounted infantry would have made short work of them under less adverse conditions.

Passing to the Chindwin, which joins the Irrawaddy at Pakokku, twenty-five miles above Myingyan, the Upper Chindwin[8] was fairly quiet. The two local potentates, the Sawbwa of Hsawnghsup and the Sawbwa of Kalè, were not of much importance. The former had made his submission; the latter was holding aloof, but had shown his goodwill by arresting and delivering to the Deputy Commissioner a pretender who had attacked a British post and was gathering to his banner various leaders. Lower down, the country round Mingin, where Mr. Gleeson, Assistant Commissioner, was murdered in 1886, was much disturbed. In the Lower Chindwin there was trouble in Pagyi and Pakangyi. The former country, which is covered with forests and very unhealthy, had been placed under the management of Burmans of local influence—a plan which answered for a time. The Kani township, which adjoins Mingin, had been governed from the first by the Burmese Wun well and loyally. He was murdered on that account by a dacoit leader. His younger brother was appointed in his room and followed in his steps. On the left bank the country was not openly disturbed. The river trade was busy, but boats were obliged to take a guard or to be convoyed by a steam-launch.

At this time the cause of order seemed nearer victory in the Eastern Division than elsewhere. The Sittang Valley includes the Kyauksè district, which at first was placed under the Commissioner of the Central Division, but was allied in dacoit politics to Meiktila. Myat Hmon, Maung Gyi, and Maung Lat, names well known to soldiers in 1885-6, hunted this country, making the Hmawwaing jungles their rallying-ground. When hard-pressed they took refuge in the hills of Baw and Lawksawk, coming back when the troops retired. In the three districts of Meiktila, Yamèthin, and Pyinmana, which then formed the Eastern Division under Mr. H. St. George Tucker, General Sir William Lockhart had given them no rest day or night. Nevertheless, in March, 1887, large bands were still active.

The Shan States were in a very troubled state, but a good beginning had been made, and Mr. Hildebrand had nearly succeeded in breaking up the Limbin Confederacy (vide Chapter XV.). But throughout the plateau dacoities were rife and petty wars were raging. Wide tracts were laid waste, and the peasantry, deserting their fields, had joined in the fights or gone across the Salween. Great scarcity, perhaps in some cases actual famine, resulted, not from failure of rain, but from strife and anarchy. And this reacted on Burma proper, for some of the Shan States on the border gave the dacoits encouragement and shelter.

The whole of Upper Burma at this time was in military occupation. There were one hundred and forty-one posts held by troops, and yet in wide stretches of country, in the greater part of the Chindwin Valley, in the Mogaung country and elsewhere, there was not a soldier. The tide, however, was on the turn. The officers in command of parties and posts were beginning to know the country and the game, while the dacoits and their leaders were losing heart. The soldiers had in fact completed their task, and they had done it well. What remained to be done was work for the civil administrator.

The first and essential step was to enable the civil officers to get a firm grip of their districts. For this purpose a civil police force, recruited from the natives of the country, was necessary. Without it, detection and intelligence were impossible. Commissioners and generals were alike unanimous on this point.

The next thing was to provide an armed force at the disposal of the district officer, so that he should be able to get an escort immediately—for there was no district where an Englishman could yet travel safely without an armed escort—and should be able also to quell risings and disperse ordinary bands of insurgents or brigands without having to ask assistance from the army. The military police had been designed and raised for these purposes, and the men were being distributed as fast as they arrived from India.

The relations of the district officers to the commandants of military police and of the latter to the civil police officers, and the duties and spheres of each, had to[35] be defined. I had drafted regulations for these purposes, and was waiting for the appointment of an Inspector-General to carry them out. It had been decided before I left Calcutta that a soldier should be selected for this post. The military police force was in fact an army of occupation sixteen thousand strong. Many of them were old soldiers who had volunteered from the Indian regiments, the rest were recruited mainly from the fighting races of Northern India. And they were commanded by young officers, some of whom had come with somewhat exalted ideas of their independence. It was imperative, therefore, to get an able soldier who could look at matters from all points of view, and who could manage men as well as command them. For it required a delicate touch to avoid friction between the military and civil members of the district staff. Some of the civil officers were young, some were quite without experience, and some were inferior to the military commandants in force and ability.