Project Gutenberg's An American Girl in London, by Sara Jeannette Duncan This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: An American Girl in London Author: Sara Jeannette Duncan Illustrator: F. H. Townsend Release Date: June 10, 2014 [EBook #45925] [Last updated: September 14, 2020] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN AMERICAN GIRL IN LONDON *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

I have written this account only secondarily and at the instigation of publishers, for Americans. Primarily, I wrote it for the English people. I composed it in their country; it was suggested by their institutions, and it is addressed to them. You will see, if you read it, that I had reasons for doing this. The reasons are in the first chapter, at the very beginning. As you have not far to look for them, therefore, and as it is quite unnecessary to print a thing twice in the same book, I will not go over them again. The object of this preface is chiefly to draw your attention to the fact that I am not talking to you, dear compatriot, so that you will understand that there is no personal ground for any annoyance you may feel at what I say.

Notwithstanding this, one of the Miss Wastgoggles, of Boston, has already taken the trouble to send me a rather severely reproachful letter about my impressions and experiences, in which she says that she would have written hers, if it had ever occurred to her to do so, very differently. I have no doubt that this is true. She also begs me to remember that there are a great many different kinds of girls in America, numbers of whom are brought up "quite as they are in England." It is this remark of hers that makes me quote Miss Wastgoggles. I wish to say in connection with it that, while it is unreasonable to apologize for being only one kind of American girl, I do not pretend to represent the ideas of any more.

Mamie Wick.

No. 4000 Prairie Avenue, Chicago, Illinois,

November 20, 1890.

AM an American Girl. Therefore, perhaps, you will not be surprised at anything further I may have to say for myself. I have observed, since I came to England, that this statement, made by a third person in connection with any question of my own conduct, is always broadly explanatory. And as my own conduct will naturally enter more or less into this volume, I may as well make it in the beginning, to save complications.

It may be necessary at this point to explain further. I know that in England an unmarried person, of my age, is not expected to talk much, especially about herself. This was a little difficult for me to understand at first, as I have always talked a great deal, and, one might say, been encouraged to do it; but I have at length been brought to understand it, and lately I have spoken with becoming infrequency, and chiefly about the Zoo. I find the Zoo to be a subject which is almost certain to be received with approval; and in animal nature there is, fortunately, a good deal of variety. I do not intend, however, in this book, to talk about the Zoo, or anything connected with it, but about the general impressions and experiences I have received in your country; and one of my reasons for departing from approved models of discussion for young ladies and striking out, as it were, into subject-matter on my own account, is that I think you may find it more or less interesting. I have noticed that you are pleased, over here, to bestow rather more attention upon the American Girl than upon any other kind of American that we produce. You have taken the trouble to form opinions about her—I have heard quantities of them. Her behaviour and her bringing-up, her idioms and her 'accent'—above all her 'accent'—have made themes for you, and you have been good enough to discuss them—Mr. James, in your midst, correcting and modifying your impressions—with a good deal of animation, for you. I observe that she is almost the only frivolous subject that ever gets into your newspapers. I have become accustomed to meeting her there, usually at the breakfast-table, dressed in green satin and diamonds. The encounter had quite a shock of novelty for me at first, but that wore off in time; the green satin and diamonds were so invariable.

Being an American girl myself, I do not, naturally, quite see the reason of this, and it is a matter I feel a delicacy about inquiring into, on personal grounds. Privately, I should think that the number of us that come over here every summer to see the Tower of London and the National Gallery, and visit Stratford-upon-Avon, to say nothing of those who marry and stay in England, would have made you familiar with the kind of young women we are long ago; and to me it is very curious that you should go on talking about us. I can't say that we object very much, because, while you criticise us considerably as a class, you are very polite to us individually, and nobody minds being criticised as a noun of multitude. But it has occurred to me that, since so much is to be said about the American Girl, it might be permissible for her to say some of it herself.

I have learned that in England you like to know a great deal about people who are introduced to you—who their fathers and mothers are, their grandfathers and grandmothers, and even further back than that.

So I will gratify you at once on this point, so far as I am able. My father is Mr. Joshua P. Wick, of Chicago, Ill.—you may have seen his name in connection with the baking-powder interest in that city. That is how he made his fortune—in baking-powder; as he has often said, it is to baking-powder that we owe everything. He began by putting it up in small quantities, but it is an article that is so much used in the United States, and ours was such a very good kind, that the demand for it increased like anything; and though we have not become so rich as a great many people in America, it is years since poppa gave his personal superintendence to the business. You will excuse my spelling it 'poppa'; I have called him that all my life, and 'papa' doesn't seem to mean anything to me.

Lately he has devoted himself to politics; he is in Congress now, and at the next election momma particularly wishes him to run for senator. There is a great deal of compliance about poppa, and I think he will run.

Momma was a Miss Wastgaggle, of Boston, and she was teaching school in Chicago when poppa met her. Her grandfather, who educated her, was a manufacturer of glass eyes. There are Wastgaggles in Boston now, but they spell the name with one 'g,' and lately they have been wanting momma to write hers 'Mrs. Wastgagle-Wick; but momma says that since she never liked the name well enough to give it to any of her children, she is certainly not going to take it again herself. These Wastgagles speak of our great-grandfather as a well-known oculist, and I suppose, in a sense, he was one.

My father's father lived in England, and was also a manufacturer, poppa says, always adding, 'in a plain way;' so I suppose whatever he made he made himself. It may have been boots, or umbrellas, or pastry—poppa never states; though I should be disposed to think, from his taking up the baking-powder idea, that it was pastry.

I am sorry that I am not able to give you fuller satisfaction about my antecedents. I know that I must have had more than I have mentioned, but my efforts to discover them—and I have made efforts since I decided to introduce myself to you—have been entirely futile. I am inclined to think that they were not people who achieved any great distinction in life; but I have never held anything against them on that account, for I have no reason to believe that they would not have been distinguished if they could. I cannot think that it has ever been in the nature of the Wicks, or the Wastgaggles either, to let the opportunity for distinction pass through any criminal negligence on their part. I am perfectly willing to excuse them on this ground, therefore; and if I, who am most intimately concerned in the matter, can afford to do this, perhaps it is not unreasonable to expect it of you.

In connections we do better. A grand-aunt of some early Wastgaggles was burned as a witch in Salem, Mass.—a thing very few families can point back to, even in England, I should think; and a second cousin of momma's was the first wife of one of our Presidents. He was a Democratic President, though, and as poppa always votes the Republican ticket, we don't think much of that. Besides, as we are careful to point out whenever we mention the subject, she was in the cemetery years before he was in the White House. And there is Mrs. Portheris, of Half-Moon Street, Hyde Park, who is poppa's aunt by her first marriage.

We were all coming at first, poppa, and momma, and I—the others are still in school—and it had appeared among the 'City Personals' of the 'Chicago Tribune' that 'Colonel and Mrs. Joshua P. Wick, accompanied by Miss Mamie Wick'—I forgot to say that poppa was in the Civil War—'would have a look at monarchical institutions this summer.' Our newspapers do get hold of things so. But just a week before we were to sail something arose—I think it was a political complication—to prevent poppa's going, and momma is far too much of an invalid to undertake such a journey without him. I must say that both my parents are devoted to me, and when I said I thought I'd prefer going alone to giving up the trip, neither of them opposed it. Momma said she thought I ought to have the experience, because, though I'd been a good deal in society in Chicago, she didn't consider that that in itself was enough. Poppa said that the journey was really nothing nowadays, and he could easily get me a letter of introduction to the captain. Besides, in a shipful of two or three hundred there would be sure to be some pleasant people I could get acquainted with on the voyage. Mrs. Von Stuvdidyl, who lives next door to us, and has been to Europe several times, suggested that I should take a maid, and momma rather liked the idea, but I persuaded her out of it. I couldn't possibly have undertaken the care of a maid.

And then we all thought of Mrs. Portheris.

None of us had ever seen her, and there had been very little correspondence; in fact, we had not had a letter from her since several years ago, when she wrote a long one to poppa, something about some depressed California mining stock, I believe, which she thought poppa, as her nephew and an American, ought to take off her hands before it fell any lower. And I remember that poppa obliged her: whether as an American or as her nephew I don't know. After that she sent us every year a Christmas card, with an angel or a bunch of forget-me-nots on it, inscribed, 'To my nephew and niece, Joshua Peter and Mary Wick, and all their dear ones.' Her latest offering was lying in the card-basket on the table then, and I am afraid we looked at it with more interest than we had ever done before.

The 'dear ones' read so sympathetically that momma said she knew we could depend upon Mrs. Portheris to take me round and make me enjoy myself, and she wanted to cable that I was coming. But poppa said No, his aunt must be getting up in years now, and an elderly English lady might easily be frightened into apoplexy by a cablegram. It was a pity there was no time to write, but I must just go and see her immediately, and say that I was the daughter of Joshua P. Wick, of Chicago, and she would be certain to make me feel at home at once. But, as I said, none of us knew Mrs. Portheris.

I AM not much acquainted in New York, so I had only poppa and Mr. Winterhazel to see me off. Mr. Winterhazel lives there, and does business in Wall Street, where he operates very successfully, I've been told, for such a young man. We had been the greatest friends and regular correspondents for three or four years—our tastes in literature and art were almost exactly the same, and it was a mutual pleasure to keep it up—but poppa had never met him before. They were very happy to make each other's acquaintance, though, and became quite intimate at once; they had heard so much about each other, they said. We had allowed two days before the steamer sailed, so that I could make some purchases—New York styles are so different from Chicago ones; and, as poppa said afterwards, it was very fortunate that Mr. Winterhazel was there. Otherwise, I should have been obliged to go round to the stores alone; for poppa himself was so busy seeing people about political matters that he hadn't the thirtieth part of a second for me, except at meal-times, and then there was almost always somebody there. London is nothing to New York for confusion and hurry, and until you get accustomed to it the Elevated is apt to be very trying to your nerves. But Mr. Winterhazel was extremely kind, and gave up his whole time to me; and as he knew all the best stores, this put me under the greatest obligation to him. After dinner the first evening he took me to hear a gentleman who was lecturing on the London of Charles Dickens, with a stereopticon, thinking that, as I was going to London, it would probably be of interest to me—and it was. I anticipated your city more than ever afterwards. Poppa was as disappointed as could be that he wasn't able to go with us to the lecture; but he said that politics were politics, and I suppose they are.

Next day I sailed from North River Docks, Pier No. 2, a fresh wind blowing all the harbour into short blue waves, with the sun on them, and poppa and Mr. Winterhazel taking off their hats and waving their handkerchiefs as long as I could see them. I suppose I started for Great Britain with about as many comforts as most people have—poppa and Mr. Winterhazel had almost filled my state-room with flowers, and I found four pounds of caramels under the lower berth—but I confess, as we steamed out past Staten Island, and I saw the statue of Liberty getting smaller and smaller, and the waves of the Atlantic Ocean getting bigger and bigger, I felt very much by myself indeed, and began to depend a good deal upon Mrs. Portheris.

As to the caramels, in the next three hours I gave the whole of them to the first stewardess, who was kind enough to oblige me with a lemon.

Before leaving home I had promised everybody that I would keep a diary, and most of the time I did; but I find nothing at all of interest in it about the first three days of the voyage to London. The reason was that I had no opportunity whatever of making observations. But on the morning of the fourth day I was obliged to go on deck. The stewardess said she couldn't put up with it any longer, and I would never recover if I didn't; and I was very glad afterwards that I gave in. She was a real kind-hearted stewardess, I may say, though her manner was a little peremptory.

I didn't find as much sociability on deck as I expected. I should have thought everybody would have been more or less acquainted by that time, but, with the exception of a few gentlemen, people were standing or sitting round in the same little knots they came on board in. And yet it was very smooth. I was so perfectly delighted to be well again that I felt I must talk to somebody, so I spoke to one of a party of ladies from Boston who I thought might know the Wastgagles there. I was very polite, and she did not seem at all sea-sick, but I found it difficult to open up a conversation with her. I knew that the Bostonians thought a good deal of themselves—all the Wastgagles do—and her manner somehow made me think of a story I once heard of a Massachusetts milestone, marked '1 m. from Boston,' which somebody thought was a wayside tablet with the simple pathetic epitaph, 'I'm from Boston,' on it; and just to enliven her I told her the story. 'Indeed!' she said. 'Well, we are from Boston.'

I didn't quite know what to do after that, for the only other lady near me was English, I knew by her boots. Beside the boots she had grey hair and pink cheeks, and rather sharp grey eyes, and a large old-fashioned muff, and a red cloud. Only an Englishwoman would be wearing a muff and a cloud like that in public—nobody else would dare to do it. She was rather portly, and she sat very firmly and comfortably in her chair with her feet crossed, done up in a big Scotch rug, and being an English woman I knew that she would not expect anybody to speak to her who had not been introduced. She would probably, I thought, give me a haughty stare, as they do in novels, and say, with cold repression, 'You have the advantage of me, miss!'—and then what would my feelings be? So I made no more advances to anybody, but walked off my high spirits on the hurricane-deck, thinking about the exclusiveness of those Bostonians, and wondering whether, as a nation, we could be catching it from England.

You may imagine my feelings—or rather, as you are probably English, you can't—when the head steward gave me my place at the dinner-table immediately opposite the Bostonians, and between this lady and an unknown gentleman. 'I shall not make a single travelling acquaintance!' I said to myself as I sat down—and I must say I was disappointed. I began to realise how greatly we had all unconsciously depended upon my forming nice travelling acquaintances, as people always do in books, to make the trip pleasant, and I thought that in considering another voyage I should divorce myself from that idea beforehand. However, I said nothing, of course, and found a certain amount of comfort in my soup.

I remember the courses of that dinner very well, and if they were calculated to make interesting literary matter I could write them out. The Bostonians ostentatiously occupied themselves with one another. One of them took up a position several miles behind her spectacles, looked at me through them, and then said something to her neighbour about 'Daisy Miller,' which the neighbour agreed to. I know what they meant now. The gentleman, when he was not attending to his dinner, stared at the salt-cellar most of the time, in a blank, abstracted way; and the English lady, who looked much nicer unshelled than she did on deck, kept her head carefully turned in the other direction, and made occasional remarks to an elderly person next her who was very deaf. If I had not been hungry, I don't know how I should have felt. But I maintained an absolute silence and ate my dinner.

Gradually—perhaps because the elderly person was so extremely deaf, and my own behaviour comparatively unaggressive—the lady of England began to assume a less uncomfortable position. A certain repellent air went out of her right shoulder. Presently she sat quite parallel with the table. By the advent of the pudding—it was cabinet pudding—I had become conscious that she had looked at me casually three times. When the Gorgonzola appeared I refused it. In America ladies eat very little Gorgonzola.

'Don't you like cheese?' she said, suddenly, a little as if I had offended her. I was so startled that I equivocated somewhat.

'No'm, not to day, I think—thank you!' I said. The fact is, I never touch it.

'Oh!' she responded. 'But then, this is your first appearance, I suppose? In that case, you wouldn't like it.' And I felt forgiven.

She said nothing more until dessert, and then she startled me again. 'Have you been bad?' she inquired.

I didn't know quite what to say, it seemed such an extraordinary question, but it flashed upon me that perhaps the lady was some kind of missionary, in which case it was my duty to be respectful. So I said that I hoped not—that at least I hadn't been told so since I was a very little girl. 'But then,' I said, 'The Episcopalian Prayer-book says we're all miserable sinners, doesn't it?' The lady looked at me in astonishment.

'What has the Prayer-book to do with your being ill?' she exclaimed. 'Oh, I see!' and she laughed very heartily. 'You thought I meant naughty! Cross-questions and crooked answers! Mr. Mafferton, you will appreciate this!' Mr. Mafferton was the gentleman whom I have mentioned in connection with the salt-cellars; and my other neighbour seemed to know him, which, as they both came from England, did not surprise me then, although now I should be inclined to consider that the most likely reason of all why they shouldn't be acquainted. I didn't see anything so very humorous in it, but the lady explained our misunderstanding to Mr. Mafferton as if it were the greatest joke imaginable, and she had made it herself. 'Really,' she said, 'it's good enough for "Punch!'" I was unfamiliar with that paper then, and couldn't say; but now I think it was myself.

Mr. Mafferton coloured dreadfully—I omitted to say that he was a youngish gentleman—and listened with a sort of strained smile, which debouched into a hesitating and uncomfortable remark about 'curious differences in idioms.' I thought he intended it to be polite, and he said it in the most agreeable man's voice I had ever heard; but I could not imagine what there was to flurry him so, and I felt quite sorry for him. And he had hardly time to get safely back to the salt-cellar before we all got up.

Next morning at breakfast I got on beautifully with the English lady, who hardly talked to the elderly deaf person at all, but was kind enough to be very much interested in what I expected to see in London. 'Your friends will have their hands full,' she remarked, with a sort of kind acerbity, 'if they undertake to show you all that!' I thought of poor old Mrs. Portheris, who was probably a martyr to rheumatism and neuralgia, with some compunction. 'Oh!' I said, 'I shouldn't think of asking them to; I'll read it all up, and then I can go round beautifully by myself!'

'By yourself!' she exclaimed. 'You! This is an independent American young lady—the very person I went especially to the United States to see, and spent a whole season in New York, going everywhere, without coming across a single specimen! You must excuse my staring at you. But you'll have to get over that idea. Your friends will never in the world allow it—I suppose you have friends?'

'No,' I said; 'only a relation.'

The lady laughed. 'Do you intend that for a joke?' she asked. 'Well, they do mean different things sometimes. But we'll see what the relation will have to say to it.'

Mr. Mafferton occasionally removed his eyes from the salt-cellar during this meal, and even ventured a remark or two. The remarks were not striking in any way—there was no food for thought in them whatever; yet they were very agreeable. Whether it was Mr. Mafferton's voice, or his manner, or his almost apologetic way of speaking, as if he knew that he was not properly acquainted, and ought not to do it, I don't know, but I liked hearing him make them. It was not, however, until later in the day, when I was sitting on deck talking with the lady from England about New York, where she didn't seem to like anything but the air and the melons, that I felt the least bit acquainted with Mr. Mafferton. I had found out her name, by the way. She asked me mine, and when I told her she said: 'But you're old enough now to have a Christian name—weren't you christened Mary?' She went on to say that she believed in the good old-fashioned names, like Nancy and Betsy, that couldn't be babified—and I am not sure whether she told me, or it was by intuition, that I learned that hers was Hephzibah. It seems to me now that it never could have been anything else. But I am quite certain she added that her husband was Hector Torquilin, and that he had been dead fifteen years. 'A distinguished man in his time, my dear, as you would know if you had been brought up in an English schoolroom.' And just then, while I was wondering what would be the most appropriate thing to say to a lady who told you that her husband had been dead fifteen years, and was a distinguished man in his time, and wishing that I had been brought up in an English schoolroom, so that I could be polite about him, Mr. Mafferton came up. He had one of Mr. W. D. Howells' novels in his hand, and at once we glided into the subject of American literature. I remember I was surprised to find an Englishman so good-natured in his admiration of some of our authors, and so willing to concede an American standard which might be a high one, and yet have nothing to do with Dickens, and so appreciative generally of the conditions which have brought about our ways of thinking and writing. We had a most delightful conversation—I had no idea there was so much in Mr. Mafferton—and Mrs. Torquilin only interrupted once. That was to ask us if either of us had ever read the works of Fennimore Cooper, who was about the only author America had ever produced. Neither of us had, and I said I thought there were some others. 'Well,' she said, 'he is the only one we ever hear of in England.' But I don't think Mrs. Torquilin was quite correct in this statement, because since I have been in England I have met three or four people, beside Mr. Mafferton, who knew, or at least had heard of, several American writers. Then Mrs. Torquilin went to sleep, and when she woke up it was five o'clock, and her maid was just arriving with her tea. Mr. Mafferton asked me if he might get me some, but I said. No, thanks; I thought I would take a brisk walk instead, if Mrs. Torquilin would excuse me.

'Certainly,' she said; 'go and take some exercise, both of you. It's much better for young people than tea-drinking. And see here, my dear! I thought you were very sensible not to dress for dinner last night, like those silly young fools opposite. Silly young fools I call them. Now, take my advice, and don't let them persuade you to do it. An Atlantic steamer is no place for bare arms. Now run away, and have your walk, and Mr. Mafferton will see that you're not blown overboard.'

Mr. Mafferton hesitated a moment. 'Are you quite sure, he said, 'that you wouldn't prefer the tea?'

'Oh yes, sir!' I said; 'we always have tea at half-past six at home, and I don't care about it so early as this. I'd much rather walk. But don't trouble to come with me if you would like some tea.'

'I'll come,' he said, 'if you won't call me "sir."' Here he frowned a little and coloured. 'It makes one feel seventy, you know. May I ask why you do it?'

I explained that in Chicago it was considered polite to say 'ma'am' or 'sir' to a lady or gentleman of any age with whom you did not happen to be very well acquainted, and I had heard it all my life; still, if he objected to it, I would not use it in his case.

He said he thought he did object to it—from a lady; it had other associations in his ears.

So I stopped calling Mr. Mafferton 'sir'; and since then, except to very old gentlemen, I have got out of the way of using the expression. I asked him if there was anything else that struck him as odd in my conversation kindly to tell me, as of course I did not wish to be an unnecessary shock to my relation in Half-Moon Street. He did not say he would, but we seemed to get on together even more agreeably after that.

Mr. Mafferton appeared to know nobody on board but Mrs. Torquilin; and I made acquaintance with hardly anybody else, so that we naturally saw a good deal of each other, usually in the afternoons, walking up and down the deck. He lent me all his books, and I lent him all mine, and we exchanged opinions on a great variety of subjects. When we argued, he was always very polite and considerate; but I noticed one curious thing about him—I never could bring him round to my point of view. He did not seem to see the necessity of coming, although I often went round to his. This was a new experience to me in arguing with a gentleman. And he always talked very impersonally. At first this struck me as a little cold and uninterested, but afterwards I liked it. It was like drinking a very nice kind of pure cold water—after the different flavours of personality I had always been accustomed to. Mr. Mafferton only made one exception to this rule that I remember, and that was the afternoon before we landed. Then he told me particularly about his father and mother, and their tastes and occupation, also the names and ages of his brothers and sisters, and their tastes and occupations, and where he lived. But I cannot say I found him as interesting that afternoon as usual.

I need not describe the bustle and confusion of landing at Liverpool Docks in the middle of a wet April afternoon. Mrs. Torquilin had told me at breakfast not on any account to let my relations take me away before she had given me her address; but when the time came I guess—if you will allow me—she must have forgotten, because the last time I saw her she was standing under a very big umbrella, which the maid held over her, a good deal excited, and giving a great many orders about her luggage to a nervous-looking man in livery.

I easily identified mine, and got off by train for London without any trouble to speak of. We arrived rather late, though, and it was still pouring.

'What has become of your people?' asked somebody at my elbow. I turned and saw Mr. Mafferton, who must have come down by the same train.

'I didn't expect my relation to meet me,' said; 'she doesn't expect me!'

'Oh!' said Mr. Mafferton; 'you did not write to her before you sailed?'

'No,' I said. 'There wasn't time.'

'Upon my word!' said Mr. Mafferton. Then, as I suppose I looked rather surprised, he added, hastily: ''I only mean that it seems so—so uncommonly extraordinary, you know! But I would advise you, in that case, to give the bulk of your luggage into the hands of the forwarding agents, with instructions to send it early to-morrow to your friend's address. It is all you can do tonight,' said Mr. Mafferton, 'really. Of course, you will go there immediately yourself.'

'No,' I responded, firmly; 'I think not, Mr. Mafferton. My relation is very elderly, and probably in bad health. For all I know, she may have gone to bed. I must not disturb her so late. All the people I have ever known have stayed at the Métropole in London. I will go to the Métropole for to-night, and have my things sent there. To-morrow I will go and see my relation, and if she asks me to visit her I can easily telephone up for them. Thank you very much.'

Mr. Mafferton looked as sober as possible, if not a little annoyed. Then he went and got the agent's young man, and asked me to point out my things to him, which I did, and got receipts. Then he told a porter to call a cab, and put my smaller valises into it. 'I will put you in,' he said, and he gave me his arm and his umbrella, through the wettest rain I have ever experienced, to the hansom. I thanked him again very cordially, and before he said good-bye he very kindly gave me his card and address, and begged me to let him know if there was anything he could do for me.

Then I rattled away through the blurred lights of your interminable twisted streets to the Métropole, fancying I saw Westminster Abbey or St. Paul's through the rain at every turn.

When we stopped at last before the hotel, another hansom behind us stopped too, and though I am sure he didn't intend me to, I saw quite plainly through the glass—Mr. Mafferton. It was extremely kind of him to wish to be of assistance to a lady alone, especially in such weather, and I could easily understand his desire to see me to my hotel; but what puzzled me was, why he should have taken another cab!

And all night long I dreamed of Mrs. Portheris.

I ONCE visited the Wastgagles in Boston with momma. It was a visit of condolence, just after the demise of a grandmother of theirs. I was going to say, that never since that occasion had I experienced anything like the solemnity of my breakfast at the Métropole the morning after I arrived. As a sad-faced waiter with mutton-chop whiskers marshalled me across the room to an empty little white-and-silvery table beside one of the big windows, I felt, for the first time in my life, that I was being made imposing, and I objected to the feeling. The place itself did not impress me particularly—in America we are accustomed to gorgeousness in our hotels, and the mirrors and the gilding of the Métropole rather made me feel at home than otherwise; but it was the demeanour of everything that weighed upon me. My very chair lived up to its own standard of decorum; and the table seemed laid upon a pattern of propriety that it would never willingly depart from. There was an all-pervading sense of order in the air I couldn't make out exactly where it came from, but it was there, and it was fearful. The waiters spoke to each other in low tones, as if something of deep and serious importance were going on; and when I told one of them what I should like from the bill-of-fare, he bent down his ear and received my order as if it had been confidential State business I was asking him to undertake. When he came back, carrying the tray in front of him, it was almost processional. And in the interval, when I turned round to look out of the window, and saw another of those respectfully-subdued waiters standing behind my chair, quite motionless, I jumped. A great many people were getting their breakfasts, not with the cheerful alacrity which we use at home, but rather with a portentous deliberation and concentration which did not admit of much talking. The silence was broken only in one corner, where a group of Americans seemed to have got accustomed to the atmosphere. When the English breakfasters raised their eyes from their papers and eggs-and-toast, they regarded my talkative compatriots with a look which must have fairly chilled their tea. I hope nobody has ever looked at me like that in England. The Americans were from Virginia, as I could tell by their accent, and their 'c'y'arn't' and 'sis'r' and 'honey' and 'heap better.' But I have no doubt the English people, in their usual loftily comprehensive fashion, set the strangers down as 'Yankees,' and no amount of explanation could have taught them that the 'Yankees are the New Englanders, and that the name would once have been taken as an insult by a Southerner. But the Virginians were blissfully indifferent to the British estimate of themselves, and they talked as freely of their shopping and sight-seeing as they would in Delmonico's or the Brunswick. To be perfectly honest, a conviction came to me then that sometimes we don't care enough. But, for my part, I liked listening to that Virginian corner.

I'm afraid it was rather a late breakfast, and the lobby was full of people strolling in and out when I went through on my way to my room. I stood for a moment at the dining-room door looking at the lobby—I had heard so many Chicago people describe it—and I noticed in the seats that run around it, against the wall, two young women. They were leaning back nonchalantly, watching the comers and the goers. Both of them had their knees crossed, and one had her hands in her jacket pockets. A man in the seat next them, who might or might not have belonged to them, was smoking a large cigar. Two English ladies came out from breakfast behind me, stood waiting for somebody, and said one to the other: 'Look at those disgusting American girls!'

But I had seen the young women's boots. Just to be satisfied, I walked up to one of them, and asked her if she could kindly tell me when I ought to post letters for New York.

'The American maiyel goes out Wednesdays an' Satuhdays, I fancy,' the young woman replied, 'but I'm not suah; it would be saifah to ask the clahk!'

She spoke quite distinctly, so that the English ladies must have heard her, and I am afraid they saw in my glance as I went upstairs that I had intended to correct their mistake.

I started to see Mrs. Portheris at eleven o'clock on the morning of the 9th of April—a lovely day, a day which augured brightly and hopefully. I waited carefully till eleven, thinking by that time my relation would have had her breakfast in bed and been dressed, and perhaps have been helped downstairs to her own particular sunny window, where I thought I might see her faded, placid, sweet old face looking up from her knitting and out into the busy street. Words have such an inspiring effect upon the imagination. All this had emanated from the 'dear ones,' and I felt confident and pleased and happy beforehand to be a dear one. I wore one of my plainest walking-dresses—I love simplicity in dress—so as to mitigate the shock to my relation as far as I could; but it was a New York one, and it gave me a great deal of moral support. It may be weak-minded in me, but I simply couldn't have gone to see my relation in a hat and gloves that didn't match. Clothes and courage have so much to do with each other.

The porter said that I had better take 'a'ansom,' or if I walked to Charing Cross I could get 'a 'Ammersmith 'bus' which would take me to Half-Moon Street, Piccadilly. I asked him if there were any street-cars running that way. 'D'ye mean growlers, miss?' he said. 'I can get ye a growler in 'arf a minute.' But I didn't know what he meant, and I didn't like the sound of it. A 'growler' was probably not at all a proper thing for a young lady to ride in; and I was determined to be considerate of the feelings of my relation. I saw ladies in hansoms, but I had never been in one at home, and they looked very tiltuppy. Also, they went altogether too fast, and as it was a slippery day the horses attached to them sat down and rested a great deal oftener than I thought I should like. And when the animals were not poor old creatures that were obliged to sit down in this precipitate way, they danced and pranced in a manner which did not inspire me with confidence. In America our cab-horses know themselves to be cab-horses, and behave accordingly—they have none of the national theories about equality whatever; but the London quadrupeds might be the greatest Democrats going from the airs they put on. And I saw no street-cars anywhere. So I decided upon the 'Ammersmith 'bus, and the porter pointed out the direction of Charing Cross.

It seems to me now that I was what you would call 'uncommonly' stupid about it, but I hadn't gone very far before I realised that I did not quite know what Charing Cross was. I had come, you see, from a city where the streets are mostly numbered, and run pretty much in rows. The more I thought about it, the less it seemed to mean anything. So I asked a large policeman—the largest and straightest policeman, with the reddest face I had ever seen: 'Mr. Officer,' I said, knowing your fondness for titles in this country, what is Charing Cross?'

He smiled very kindly. 'Wy, miss,' he said, 'there's Charing Cross Station, and there's Charing Cross 'Otel, and there's Charing Cross. Wot were you wanting pertickeler?'

'Charing Cross!' said I.

'There it lies, in front of you!' the policeman said, waving his arm so as to take in the whole of Trafalgar Square. 'It ain't possible for you to miss it, Miss. And as three other people were waiting to ask him something else, I thought I ought not to occupy his attention any further. I kept straight on, in and out among the crowd, comparing it in my mind with a New York or Chicago crowd. I found a great many more kinds of people in it than there would be at home.

You are remarkably different in this country. We are a good deal the same. I was not at all prepared then to make a comparison of averages, but I noticed that life seemed to mean something more serious for most of the people I met than it does with us. Hardly anybody was laughing, and very few people were making unseemly haste about their business. There was no eagerness and no enthusiasm. Neither was there any hustling. In a crowd like that in Chicago everybody would have hustled, and nobody would have minded it.

'Where is Charing Cross?' I asked one of the flower-women sitting by the big iron entrances to the station. 'Right'ere, miss, ware you be a-standin'! Buy a flower, miss? Only a penny! an' lovely they are! Do buy one, laidy!' It was dreadfully pathetic, the way she said it, and she had frightful holes in her shawl, and no hat or bonnet on. I had never seen a woman selling things out of doors with nothing on her head before, and it hurt me somehow. But I couldn't possibly have bought her flowers—they were too much like her. So I gave her a sixpence, and asked her where I could find an 'Ammersmith' bus. She thanked me so volubly that I couldn't possibly understand her, but I made out that if I stayed where I was an 'Ammersmith' bus would presently arrive. She went on asking me to buy flowers though, so I walked a little farther off. I waited a long time, and not a single 'bus appeared with 'Ammersmith on it. Finally, I asked another policeman. 'There!' he said, as one of the great lumbering concerns rolled up—'that's one of 'em now! You'll get it!' I didn't like to dispute with an officer of the law, but I had seen plenty of that particular red variety of 'bus go past, and to be quite certain I said: 'But isn't that a Hammersmith one?' The policeman looked quite cross. 'Well, isn't that what you're a-askin' for? 'Ammersmith an' 'Ammersmith—it's all the saime, dependin' on 'ow you pernounces it. Some people calls it 'Ammersmith, an' some people calls it 'Ammersmith!' and he turned a broad and indignant back upon me. I flew for the 'bus, and the conductor, in a friendly way, helped me on by my elbow.

I did not think, before, that anything could wobble like an Atlantic steamer, but I experienced nothing more trying coming over than that Hammersmith 'bus. And there were no straps from the roof to hold on by—nothing but a very high and inconvenient handrail; and the vehicle seemed quite full of stout old gentlemen with white whiskers, who looked deeply annoyed when I upset their umbrellas and unintentionally plunged upon their feet. 'More room houtside, miss!' the conductor said—which I considered impertinent, thinking that he meant in the road. 'Is there any room on top?' I asked him, because I had walked on so many of the old gentlemen's feet that I felt uncomfortable about it. 'Yes, miss; that's wot I'm a-sayin'—lots o' room houtside!' So I took advantage of a lame man's getting off to mount the spiral staircase at the back of the'bus and take a seat on top. It is a pity, isn't it, that Noah didn't think of an outside spiral staircase like that to his ark. He might have accommodated so many more of the animals, providing them, of course, with oilskin covers to keep off the wet, as you do. But even coming from a bran new and irreverent country, where nobody thinks of consulting the Old Testament for models of public conveyances, anybody can see that in many respects you have improved immensely upon Noah.

It was lovely up there—exactly like coming on deck after being in a stuffy little cabin in the steamer—a good deal of motion, but lots of fresh air. I was a little nervous at first, but as nobody fell off the tops of any of the other 'buses, I concluded that it was not a thing you were expected to do, and presently forgot all about it looking at the people swarming below me. My position made me feel immeasurably superior—at such a swinging height above them all—and I found myself speculating about them and criticising them, as I never should have done walking. I had never ridden on the top of anything before; it gave me an entirely new revelation of my fellow-creatures—if your monarchical feelings will allow that expression from a Republican. I must say I liked it—looking down upon people who were travelling in the same direction as I was, only on a level below. I began to understand the agreeableness of class distinctions, and I wondered whether the arrangement of seats on the tops of the 'buses was not, probably, a material result of aristocratic prejudices.

Oh, I liked it through and through, that first ride on a London 'bus! To know just how I liked it, and why, and how and why we all like it from the other side of the Atlantic, you must be born and brought up, as most of us have been, in a city twenty-five or fifty years old, where the houses are all made of clean white or red brick, with clean green lawns and geranium beds and painted iron fences; where rows of nice new maple-trees are planted in the clean-shaved boulevards, and fresh-planed wooden sidewalks run straight for a mile or two at a time, and all the city blocks stand in their proper right angles—which are among our advantages, I have no doubt; but our advantages have a way of making your disadvantages more interesting.

Having been monarchists all your lives, however, you can't possibly understand what it is to have been brought up in fresh paint. I ought not to expect it of you. If you could, though, I should find it easier to tell you, according to my experience, why we are all so devoted to London.

There was the smell, to begin with. I write 'there was,' because I regret to say that during the past few months I have become accustomed to it, and for me that smell is done up in a past tense for ever; so that I can quite understand a Londoner not believing in it. The Hammersmith 'bus was in the Strand when I first became conscious of it, and I noticed afterwards that it was always more pronounced down there, in the heart of the City, than in Kensington, for instance. It was no special odour or collection of odours that could be distinguished—it was rather an abstract smell—and yet it gave a kind of solidity and nutriment to the air, and made you feel as if your lungs digested it. There was comfort and support and satisfaction in that smell, and I often vainly try to smell it again.

We find the irregularity of London so gratifying, too. The way the streets turn and twist and jostle each other, and lead up into nothing, and turn around and come back again, and assume aliases, and break out into circuses and stray into queer, dark courts, where small boys go round on one roller skate, or little green churchyards only a few yards from the cabs and the crowd, where there is nobody but the dead people, who have grown tired of it all.

From the top of the Hammersmith 'bus, as it went through the Strand that morning, I saw funny little openings that made me long to get down and look into them; but I had my relation to think of, so I didn't.

Then there is the well-settled, well-founded look of everything, as if it had all come ages ago, and meant to stay for ever, and just go on the way it had before. We like that—the security and the permanence of it, which seems to be in some way connected with the big policemen, and the orderly crowd, and 'Keep to the Left' on the signboards, and the British coat of arms over so many of the shops. I thought that morning that those shops were probably the property of the Crown, but I was very soon corrected about that. At home I am afraid we fluctuate considerably, especially in connection with cyclones and railway interests—we are here to-day, and there is no telling where we shall be to-morrow. So the abiding kind of city gives us a comfortable feeling of confidence. It was not very long before even I, on the top of the Hammersmith 'bus, felt that I was riding an Institution, and no matter to what extent it wobbled it might be relied upon not to come down.

I don't know whether you will like our admiring you on account of your griminess, but we do. At home we are so monotonously clean, architecturally, that we can't make any aesthetic pretensions whatever. There is nothing artistic about white brick. It is clean and neat and sanitary, but you get tired of looking at it, especially when it is made up in patterns with red brick mixed in. And since you must be dirty, it may gratify you to know that you are very soothing to Transatlantic nerves suffering from patterns like that. But you are also misleading. 'I suppose,' I said to a workman in front of me as we entered Fleet Street, 'that is some old palace? Do you know the date of it?'

'No, miss,' he answered, 'that ain't no palace. Them's the new Law Courts, only built the last ten year!'

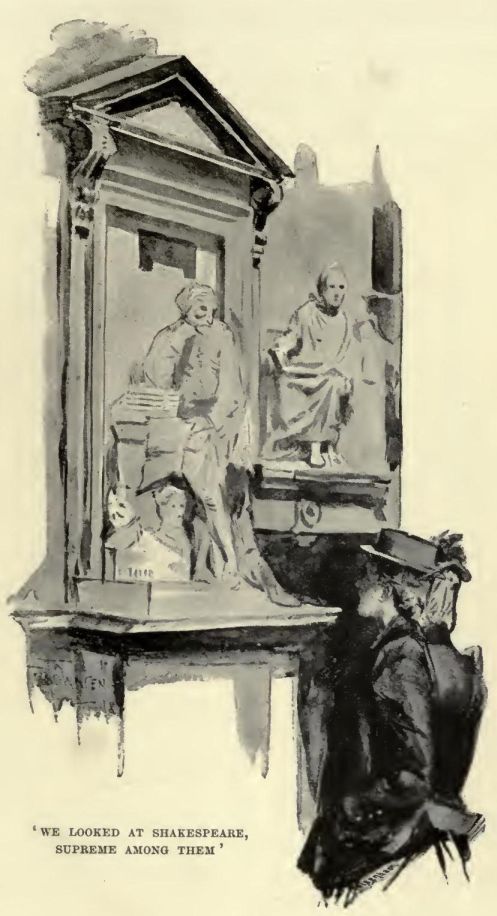

'The new Law Courts!' 'The Strand!' 'Fleet Street!' 'Ludgate Hill!' 'Cheapside!' and I was actually in those famous places, riding through them on a 'bus, part of their multitude. The very names on the street corners held fascination enough, and each of them gave me the separate little thrill of the altogether unexpected. I had unconsciously believed that all these names were part of the vanished past I had connected them with, forgetting that in London names endure. But I began to feel that I ought to be arriving. 'Conductor,' I said, as he passed, 'stop the 'bus, and let me get down at Half-Moon Street, Piccadilly.'

'We're goin' strait awai from it, miss; you get that red 'bus standin' over there—that'll taike you!'

So I went all the way back again, and on to my relation's, on the top of the red 'bus, not at all regretting my mistake. But it made it almost twelve o'clock when I rang the bell—Mrs. Portheris's bell—at the door of her house in Half-Moon Street, Piccadilly.

FROM the outside I didn't think much of Mrs. Portheris's house. It was very tall, and very plain, and very narrow, and quite expressionless, except that it wore a sort of dirty brown frown. Like its neighbours, it had a well in front of it, and steps leading down into the well, and an iron fence round the steps, and a brass bell-handle lettered 'Tradesmen.' Like its neighbours, too, it wore boxes of spotty black greenery on the window-sills—in fact, it was very like its neighbours, except that it had one or two solemn little black balconies that looked as if nobody ever sat in them running across the face of it, and a tall, shallow porch, with two or three extremely white stone steps before the front door. Half-Moon Street, to me, looked like a family of houses—a family differing in heights and complexions and the colour of its hair, but sharing all the characteristics of a family—of an old family. A person draws a great many conclusions from the outside of a house, and my conclusion from the outside of my relation's house was that she couldn't be very well off to be obliged to live in such a plain and gloomy locality, with 'Tradesmen' on the ground-floor; and I hoped they were not any noisy kind of tradesmen, such as shoemakers or carpenters, who would disturb her early in the morning. The clean-scrubbed stone steps reflected very favourably, I thought, upon Mrs. Portheris, and gave the house, in spite of its grimy, old-fashioned, cramped appearance, a look of respectability which redeemed it. But I did not see at any window, behind the spotty evergreens, the sweet, sad face of my relation, though there were a hand-organ and a monkey and a German band all operating within twenty yards of the house.

I rang the bell. The door opened a great deal more quickly than you might imagine from the time I am taking to tell about it, and I was confronted by my first surprise in London. It was a man—a neat, smooth, pale, round-faced man in livery, rather fat and very sad. It was also Mrs. Portheris's interior. This was very dark and very quiet, but what light there was fell richly, through a square, stained-glass window at the end of the hall, upon the red and blue of some old china above a door, and a collection of Indian spears, and a twisting old oak staircase that glowed with colour. Mrs. Portheris's exterior had prepared me for something different. I did not know then that in London everything is a matter of the inside—I had not seen a Duchess living crowded up to her ears with other people's windows. With us the outside counts so tremendously. An American duchess, if you can imagine such a person, would consider it only due to the fitness of things that she should have an imposing front yard, and at least room enough at the back for the clothes-lines. But this has nothing to do with Half-Moon Street.

'Does Mrs. Portheris live here?' I asked, thinking it was just possible she might have moved.

'Yes, miss,' said the footman, with a subdued note of interrogation.

I felt relieved. 'Is she—is she well?' I inquired.

'Quite well, miss,' he replied, with the note of interrogation a little more obvious.

'I should like to see her. Is she in?'

'I'll h'inquire, miss, 'n 'Oo shall I sai, miss?'

I thought I would prepare my relation gradually. 'A lady from Chicago,' said I.

'Very well, miss. Will you walk upstairs, miss?'

In America drawing-rooms are on the ground-floor. I thought he wanted to usher me into Mrs. Portheris's bedroom.

'No, sir,' I said; 'I'll wait here.' Then I thought of Mr. Mafferton, and of what he had said about saying 'sir' to people, and my sensations were awful. I have never done it once since.

The footman reappeared in a few minutes with a troubled and apologetic countenance. 'Mrs. Portheris says as she doesn't want anythink, miss! I told her as I didn't understand you were disposin' of anythink; but that was 'er message, miss.'

I couldn't help laughing—it was so very funny to think of my being taken for a lady-pedlar in the house of my relation. 'I'm very glad she's in,' I said. 'That is quite a mistake! Tell her it's Miss Mamie Wick, daughter of Colonel Joshua R. Wick, of Chicago; but if she's lying down, or anything, I can drop in again.'

He was away so long that I began to wonder if my relation suspected me of dynamite in any form, and he came back looking more anxious than ever. 'Mrs. Portheris says she's very sorry, miss, and will you please to walk up?' 'Certainly,' I said, 'but I hope I won't be disturbing her!'

And I walked up.

It was a big square room, with a big square piano in it, and long lace curtains, and two or three gilt-framed mirrors, and a great many old-fashioned ornaments under glass cases, and a tinkling glass chandelier in the middle. There were several oil-paintings on the walls—low-necked portraits and landscapes, principally dark-green and black and yellow, with cows, and quantities of lovely china. The furniture was red brocade, with spindly legs, and there was a tall palm in a pot, which had nothing to do with the rest of the room, by itself in a corner. I remembered these things afterwards.

At the time I noticed chiefly two young persons with the pinkest cheeks I ever saw, out of a picture-book, sitting near a window. They were dressed exactly alike, and their hair hung down their backs to their waists, although they must have been seventeen; and they sat up very nicely indeed on two of the red chairs, one occupied with worsted work, and the other apparently reading aloud to her, though she stopped when I came in. I have seen something since at Madame Tussaud's—but I daresay you have often noticed it yourself. And standing in the middle of the room, with her hand on a centre-table, was Mrs. Portheris.

My first impression was that she had been standing there for the last hour in that immovable way, with exactly that remarkable expression; and it struck me that she could go on standing for the next without altering it, quite comfortably—she seemed to be so solidly placed there, with her hand upon the table. Though I wouldn't call Mrs. Portheris stout, she was massive—rather, of an impressive build. Her skirt fell in a commanding way from her waist, though it hitched up a little in front, which spoiled the effect. She had broad square shoulders, and a lace collar, and a cap with pink ribbons in it, and grey hair smooth on each side of her face, and large well-cut features, and the expression I spoke of. I've seen the expression since among the Egyptian antiquities in the British Museum, but I am unable to describe it. 'Armed neutrality' is the only phrase that occurs to me in connection with it, and that by no means does it justice. For there was curiosity in it, as well as hostility and reserve—but I won't try. And she kept her hand—it was her right hand—upon the table.

'Miss Wick' she said, bowing, and dwelling upon the name with strong doubt. 'I believe I have a connection of that name in America. Is your father's name Joshua Peter?'

'Yes, Mrs. Portheris,' I replied; 'and he says he is your nephew. I've just come. How do you do?' I said this because it was the only thing the situation seemed to warrant me saying.

'Oh, I am quite in my usual health, thank you! My nephew by marriage—a former marriage—a very distant connection.'

'Three thousand five hundred miles,' said I; 'he lives in Chicago. You have never been over to see us, Mrs. Portheris. At this point I walked across to one of the spindly red chairs and sat down. I thought then that she had forgotten to ask me; but even now, when I know she hadn't, I am not at all sorry I sat down. I find it is possible to stand up too much in this country.

The old lady gathered herself up and looked at me. 'Where are your father and mother?' she said.

'In Chicago, Mrs. Portheris. All very well, thank you! I had a cable from them this morning, before I left the hotel. Kind regards to you.'

Mrs. Portheris looked at me in absolute silence. Then she deliberately arranged her back draperies and sat down too—not in any amiable way, but as if the situation must be faced.

'Margaret and Isabel,' she said to the two young pink persons, 'go to your rooms, dears!' And she waited till the damsels, each with a little shy smile and blush, gathered up their effects and went, before she continued the conversation. As they left the room I observed that they wore short dresses, buttoned down the back. It began to grow very interesting to me, after the first shock of finding this kind of relation was over. I found myself waiting for what was to come next with the deepest interest. In America we are very fond of types—perhaps because we have so few among ourselves—and it seemed to me, as I sat there on Mrs. Portheris's spindly red chair, that I had come into violent contact with a type of the most valuable and pronounced description. Privately I resolved to stay as long as I could, and lose no opportunity of observing it. And my first observation was that Mrs. Portheris's expression was changing—losing its neutrality and beginning to radiate active opposition and stern criticism, with an uncompromising sense of duty twisted in at the corners of the mouth. There was no agitation whatever, and I thought with an inward smile of my relation's nerves.

'Then I suppose,' said Mrs. Portheris—the supposition being of the vaguest possible importance—'that you are with a party of Americans. It seems to be an American idea to go about in hordes. I never could understand it—to me it would be most obnoxious. How many are there of you?'

'One, Mrs. Portheris—and I'm the one. Poppa and momma had set their hearts on coming. Poppa thought of getting up an Anglo-American Soda Trust, and momma wanted particularly to make your acquaintance—your various Christmas cards have given us all such a charming idea of you—but at the last minute something interfered with their plans and they had to give it up. They told me to tell you how sorry they were.'

'Something interfered with their plans! But nothing interfered with your plans!'

'Oh, no; it was some political business of poppa's—nothing to keep me!'

'Then do I actually understand that your parents, of their own free will, permitted you to cross the Atlantic alone?'

'I hope you do, Mrs. Portheris; but if it's not quite clear to you, I don't mind explaining it again.'

'Upon my word! And you are at an hotel—which hotel?' When I told Mrs. Portheris the Métropole, her indignation mounted to her cap, and one of the pink ribbons shook violently.

'It is very American!' she said; and I felt that Mrs. Portheris could rise to no more forcible a climax of disapproval.

But I did not mind Mrs. Portheris's disapproval; in fact, according to my classification of her, I should have been disappointed if she had not disapproved—it would have been out of character. So I only smiled as sweetly as I could, and said, 'So am I.'

'Is it not very expensive?' There was a note of angry wonder as well as horror in this.

'I don't know, Mrs. Portheris. It's very comfortable.' 'I never heard of such a thing in my life!' said Mrs. Portheris. 'It's—it's outrageous! It's—it's not customary!

I call it criminal lenience on the part of my nephew to allow it, he must have taken leave of his senses!'

'Don't say anything nasty about poppa, Mrs. Portheris,' I remarked; and she paused.

'As to your mother——'

'Momma is a lady of great intelligence and advanced views,' I interrupted, 'though she isn't very strong. And she is very well acquainted with me.'

'Advanced views are your ruin in America! May I ask how you found your way here?'

'On a 'bus, Mrs. Portheris—the red Hammersmith kind. On two 'buses, rather, because I took the wrong one first, and went miles straight away from here; but I didn't mind it—I liked it.'

'In an omnibus I suppose you mean. You couldn't very well be on it, unless you went on the top!' And Mrs. Portheris smiled rather derisively.

'I did; I went on the top,' I returned calmly. 'And it was lovely.'

Mrs. Portheris very nearly lost her self-control in her effort to grasp this enormity. Her cap bristled again, and the muscles round her mouth twitched quite perceptibly.

'Careering all over London on the top of an omnibus!' she ejaculated. 'Looking for my house! And in that frock!' I felt about ten when she talked about my 'frock.' 'Couldn't you feel that you were altogether too smart for such a position?'

'No, indeed, Mrs. Portheris!' I replied, unacquainted with the idiom. 'When I got down off the first omnibus in Cheapside I felt as if I hadn't been half smart enough!'

She did not notice my misunderstanding. By the time I had finished my sentence she was rapping the table with suppressed excitement.

'Miss Wick!' she said—and I had expected her to call me Mamie, and say I was the image of poppa!—'you are the daughter of my nephew—which can hardly be called a connection at all—but on that account I will give you a piece of advice. The top of an omnibus is not a proper place for you—I might say, for any connection of mine, however distant! I would not feel that I was doing my duty toward my nephew's daughter if I did not tell you that you must not go there! Don't on any account do it again! It is a thing people never do!'

'Do they upset?' I asked.

'They might. But apart from that, I must ask you, on personal—on family grounds—always to go inside. In Chicago you may go outside as much as you like, but in London——'

'Oh, no!' I interrupted, 'I wouldn't for the world—in Chicago!' which Mrs. Portheris didn't seem to understand.

I had stayed dauntlessly for half an hour—I was so much interested in Mrs. Portheris—and I began to feel my ability to prolong the interview growing weaker. I was sorry—I would have given anything to have heard her views upon higher education and female suffrage, and the Future State and the Irish Question; but it seemed impossible to get her thoughts away from the appalling Impropriety which I, on her spindly red chair, represented I couldn't blame her for that—I suppose no impropriety bigger than a spider had ever got into her drawing-room before. So I got up to go. Mrs. Portheris also rose, with majesty. I think she wanted to show me what, if I had been properly brought up, I might have expected reasonably to develop into. She stood in the midst of her red brocaded furniture, with her hands folded, a model of what bringing up can do if it is unflinchingly persevered in, and all the mirrors reflected the ideal she presented. I felt, beside her, as if I had never been brought up at all.

'Have you any friends in London?' she asked, with a very weak solution of curiosity in her tone, giving me her hand to facilitate my going, and immediately ringing the bell.

'I think not,' I said with, decision.

'But you will not continue to stay at the Métropole! I beg that you will not remain another day at the Métropole! It is not usual for young ladies to stay at hotels. You must go to some place where only ladies are received, and as soon as you are settled in one communicate at once with the rector of the parish—alone as you are, that is quite a necessary step, lights and fires will probably be extra.'

'I thought,' said I, 'of going to the Lady Guides' Association—we have heard of it in Chicago through some friends, who went round every day for three weeks with lady-guides, and found it simply fascinating—and asking them to get me a private family to board with. I particularly wished to see what a private family is like in England.'

Mrs. Portheris frowned. 'I could never bring myself to approve of lady-guides,' she said. 'There is something in the idea that is altogether too—American.' I saw that the conversation was likely to grow personal again, so I said: 'Well, good-bye, Mrs. Portheris!' and was just going, when 'Stop!' said my relation, 'there is Miss Purkiss.'

'Is there?' said I.

'Certainly—the very thing! Miss Purkiss is a very old friend of mine, in reduced circumstances. I've known her thirty-five years. She is an excellent woman, with the most trustworthy views upon all matters. In so far as our widely different social positions have permitted, Miss Purkiss and I have been on terms, I may say, of sisterly intimacy since before you were born. She has no occupation now, having lost her position as secretary to the Home for Incurable Household Pets through ill-health, and a very limited income. She lives in an excessively modest way in Upper Baker Street—very convenient to both the omnibuses and Underground—and if you cast in your lot with hers while you are in England, Miss Wick'—here Mrs. Portheris grew almost demonstrative—'you need never go out alone. I need not say that she is a lady, but her circumstances will probably necessitate her asking you rather more than the usual rate for board and lodging, in compensation for her chaperonage and companionship. All I can say is, that both will be very thorough. I will give you Miss Purkiss's address at once, and if you drive there immediately you will be sure to find her in. John, call a hansom!' And Mrs. Portheris went to her writing-table and wrote the address.

'There!' she said, folding it up and giving it to me. 'By all means try to arrange with Miss Purkiss, and she, being a friend of my own, some afternoon, perhaps—I must think about it—I may ask her to bring you to tea! Good-bye!'

As the door closed behind me I heard Mrs. Portheris's voice on the landing. 'Margaret and Isabel,' it said, 'you may come down now!'

'Ware to, miss?' said the driver.

'Hôtel Métropole,' said I. And as we turned into Piccadilly a little flutter of torn white paper went back on the wind to Mrs. Portheris. It was Miss Purkiss's address.

After lunch I made careful notes of Mrs. Portheris, and then spent half an hour in the midst of my trunks, looking in the Board and Lodging' column of the 'Morning Post' for accommodation which promised to differ as radically as possible from Miss Purkiss's.

MY principal idea was to get away as soon as possible from the Métropole. So long as I was located there I was within the grasp of my relation; and as soon as she found out my insubordination in the matter of her advice, I had no doubt whatever that my relation would appear, with Miss Purkiss, all in rusty black, behind her—a contingency I wished to avoid. Miss Purkiss, I reflected, would probably be another type, and types were interesting, but not to live with—my relation had convinced me of that. And as to Mrs. Portheris herself, while I had certainly enjoyed what I had been privileged to see of her, her society was a luxury regarding which I felt that I could exercise considerable self-denial. I did not really contemplate being forced into Miss Purkiss and Upper Baker Street by Mrs. Portheris against my will, not for a moment; but I was afraid the situation would be presented on philanthropic grounds, which would be disagreeable. Miss Purkiss as a terror I felt equal to, but Miss Purkiss as an object of charity might cow me. And Miss Purkiss in any staying capacity was not, I felt, what I came to Great Britain to experience. So I studied the columns of the 'Morning Post' diligently for a haven of refuge from Miss Purkiss.

I found it difficult to make a selection, the havens were so very different, and all so superior. I believe you talk about the originality of American advertising. I never in my life saw a newspaper page to compare in either imagination or vocabulary with the one I scanned that day at the Métropole. It seemed that I could be taken all over London, at prices varying from one 'g.' to three 'gs.' per week, although the surprising cheapness of this did not strike me until I had laboriously calculated in dollars and cents the exact value of a 'g.' I know now that it is a term of English currency exclusively employed in Bond Street, Piccadilly, Regent and Oxford Streets—they never give you a price there in any other. And the phrases descriptive of the various homes which were awaiting me were so beautiful. 'Excellent meat breakfast,' 'a liberal and charmingly-refined home,' 'a mother's devoted supervision,' 'fresh young society,' 'fashionably situated and elegantly furnished,' 'just vacated by a clergyman,' 'foreign languages understood'—which would doubtless include American—'a lofty standard of culture in this establishment.' I wondered if they kept it under glass. I was struck with the number of people who appeared in print with 'offerings' of a domiciliary nature. 'A widow lady of cheerful temperament and artistic tastes offers——' 'The daughter of a late Civil Servant with a larger house than she requires offers——' This must have been a reference put in to excite sympathy, otherwise, what was the use of advertising the gentleman after he was dead? Even from the sympathetic point of view, I think it was a mistake, for who would care to go and settle in a house the minute the crape was off the door? Nobody.

Not only original advertisements of the kind I was looking for, but original advertisements of kinds I wasn't looking for, appealed to my interest and took up my time that afternoon.

'Would any one feel disposed to lend an actress five pounds?

'Temporary home wanted, with a family of quiet habits, in a healthful neighbourhood, who can give best references, for a Persian cat.' 'An elderly country rector and his wife, in town for a month's holiday, would be glad of a little pleasant society.'

'A young subaltern, of excellent family, in unfortunate circumstances, implores the loan of a hundred pounds to save him from ruin. Address, care of his solicitors.' 'A young gentleman, handsome, an orphan, of good education and agreeable address, wishes to meet with elderly couple with means (inherited) who would adopt him. Would make himself pleasant in the house. Church of England preferred, but no serious objection to Nonconformists.'

We have nothing like this in America. It was a revelation to me—a most private and intimate revelation of a social body that I had always been told no outsider could look into without the very best introductions. Of course, there was the veil of 'A. B.' and 'Lurline,' and the solicitors' address, but that seemed as thin and easily torn as the 'Morning Post,' and much more transparent, showing all the struggling mass, with its hands outstretched, on the other side. And yet I have heard English people say how 'personal' our newspapers are!

My choice was narrowed considerably by so many of the addresses being other places than London, which I thought very peculiar in a London newspaper. Having come to see London, I did not want to live in Putney, or Brixton, or Chelsea, or Maida Vale. I supposed vaguely that there must be cathedrals or Roman remains, or attractions of some sort, in these places, or they would not be advertised in London; but for the time being, at any rate, I intended to content myself with the capital. So I picked out two or three places near the British Museum—I should be sure, I thought, to want to spend a great deal of time there—and went to see about them.

They were as much the same as the advertisements were different, especially from the outside. From the outside they were exactly alike—so much so that I felt, after I had seen them all, that if another boarder in the same row chose to approach me on any occasion, and say that she was me, I should be entirely unable to contradict her. This in itself was prejudicial. In America, if there is one thing we are particular about, it is our identity. Without our identities we are in a manner nowhere. I did not feel disposed to run the risk of losing mine the minute I arrived in England, especially as I knew that it is a thing Americans who stay here for any length of time are extremely apt to do. Nevertheless, I rang the three door-bells I left the Métropole with the intention of ringing; and there were some minor differences inside, although my pen insists upon recording the similarities instead. I spent the same length of time upon the doorstep, for instance, before the same tumbled and apologetic-looking servant girl appeared, wiping her hands upon her apron, and let me into the same little dark hall, with the same interminable stairs twisting over themselves out of it, and the smell of the same dinner accompanying us all the way up. To be entirely just, it was a wholesome dinner, but there was so much of it in the air that I very soon felt as if I was dining unwarrantably, and ought to pay for it. In every case the stair-carpet went up two flights, and after that there was oilcloth, rather forgetful as to its original pattern, and much frayed as to its edges—and after that, nothing. Always pails and brushes on the landings—what there is about pails and brushes that should make them such a distinctive feature of boarding-house landings I don't know, but they are. Not a single elevator in all three. I asked the servant-girl in the first place, about half-way up the fourth flight, if there was no elevator? 'No, indeed, miss,' she said: 'I wishes there was! But them's things you won't find but very seldom 'ere. We've 'ad American ladies 'ere before, and they allus asks for 'em, but they soon finds out they ain't to be 'ad, miss.'

Now, how did she know I was an 'American lady'? I didn't really mind about the elevator, but this I found annoying, in spite of my desire to preserve my identity. In the course of conversation with this young woman, I discovered that it was not my own possibly prospective dinner that I smelt on the stairs. I asked about the hour for meals. 'Aou, we never gives meals, miss!' she said. 'It's only them boardin' 'aouses as gives meals in! Mrs. Jones, she only lets apartments. But there's a very nice restirong in Tottinim Court Road, quite convenient, an' your breakfast, miss, you could 'ave cooked 'ere, but, of course, it would be hextra, miss.'

Then I remembered all I had read about people in London living in 'lodgings,' and having their tea and sugar and butter and eggs consumed unrighteously by the landlady, who was always represented as a buxom person in calico, with a smut on her face, and her arms akimbo, and an awful hypocrite. For a minute I thought of trying it, for the novelty of the experience, but the loneliness of it made me abandon the idea. I could not possibly content myself with the society of a coal-scuttle and two candlesticks, and the alternative of going round sightseeing by myself. Nor could I in the least tell whether Mrs. Jones was agreeable, or whether I could expect her to come up and visit with me sometimes in the evenings; besides, if she always wore smuts and had her arms akimbo, I shouldn't care about asking her. In America a landlady might as likely as not be a member of a Browning Society, and give 'evenings,' but that kind of landlady seems indigenous to the United States. And after Mrs. Portheris, I felt that I required the companionship of something human.

In the other two places I saw the landladies themselves in their respective drawing-rooms on the second floor. One of the drawing-rooms was 'draped' in a way that was quite painfully aesthetic, considering the paucity of the draperies. The flower-pots were draped, and the lamps; there were draperies round the piano-legs, and round the clock; and where there were not draperies there were bows, all of the same scanty description. The only thing that had not made an effort to clothe itself in the room was the poker, and by contrast it looked very nude. There were some Japanese ideas around the room, principally a paper umbrella; and a big painted palm-leaf fan from India made an incident in one corner. I thought, even before I saw the landlady, that it would be necessary to live up to a high standard of starvation in that house, and she confirmed the impression. She was a Miss Hippy, a short, stoutish person, with very smooth hair, thin lips, and a nose like an angle of the Pyramids, preternaturally neat in her appearance, with a long gold watch-chain round her neck. She came into the room in a way that expressed reduced circumstances and a protest against being obliged to do it. I feel that the particular variety of smile she gave me with her 'Good morning!'—although it was after 4 P.M.—was one she kept for the use of boarders only, and her whole manner was an interrogation. When she said, 'Is it for yourself?' in answer to my question about rooms, I felt that I was undergoing a cross-examination, the result of which Miss Hippy was mentally tabulating.

'We have a few rooms,' said Miss Hippy, 'certainly.' Then she cast her eyes upon the floor, and twisted her fingers up in her watch-chain, as if in doubt. 'Shall you be long in London?'

I said I couldn't tell exactly.

'Have you—are you a professional of any kind?' inquired Miss Hippy. 'Not that I object to professional ladies—they are often very pleasant. Madame Solfreno resided here for several weeks while she was retrenching; but Madame Solfreno was, of course, more or less an exceptional woman. She did not care—at least, while she was retrenching—for the society of other professionals, and she said that was the great advantage of my house—none of them ever would come here. Still, as I say, I have no personal objection to professionals. In fact, we have had head-ladies here; and real ladies, I must say, I have generally found them. Although hands, of course, I would not take!'

I said I was not a professional.

'Oh!' said Miss Hippy, pitiably baffled. 'Then, perhaps, you are not a—a young lady. That is, of course, one can see you are that; but you are—you are married, perhaps?'

'I am not married, madame,' I said. 'Have you any rooms to let?'

Miss Hippy rose, ponderingly. 'I might as well show you what we have,' she said.