This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Verdi: Man and Musician

His Biography with Especial Reference to His English Experiences

Author: Frederick James Crowest

Release Date: July 17, 2014 [eBook #46316]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VERDI: MAN AND MUSICIAN***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/verdimanmusician00crow |

There are 5 illustrations, placed where they appear in the book. A list of these illustrations with a link to each of them can be found below the table of contents.

There are many footnotes, numbered consecutively from 1 to 83; each of them is placed at the end of the chapter where it is referenced.

VERDI:

man and musician

| BY THE SAME AUTHOR. |

| "THE STORY OF BRITISH MUSIC." |

| "CHERUBINI" ("GREAT MUSICIANS" SERIES). |

| "PHASES OF MUSICAL ENGLAND." |

| "ADVICE TO SINGERS." (12th Thousand.) |

| Etc. Etc. |

His Biography with Especial

Reference to his English

Experiences

By

Frederick J. Crowest

Author of

"The Great Tone Poets," etc.

john milne

12 norfolk street, strand

london

mdcccxcvii

To

MADAME ADELINA PATTI NICOLINI

EMPRESS OF SONG

Whose Transcendent Vocal and Histrionic Powers

HAVE

Contributed so largely to an adequate appreciation

of the genius of

VERDI

This Monograph of the Master is

by Expressed Permission

DEDICATED

BIRTH, PARENTAGE, AND CHILD-LIFE

Verdi's birth and birth-place—Dispute as to his township—Baptismal certificate—His parentage—The parents' circumstances—The osteria kept by them—A regular market-man—A mixed business—Verdi's early surroundings and influences—Verdi not a musical wonder or show-child—His natural child-life—Enchanted with street organ—Quiet manner as a child—Acolyte at Roncole Church—Enraptured with the organ music—Is bought a spinet—Practises incessantly—Gratuitous spinet repairs—To school at Busseto—Slender board and curriculum—First musical instruction—An apt pupil

CLERK, STUDENT, AND PROFESSOR

Verdi goes into the world—Office-boy in Barezzi's establishment—Congenial surroundings—An exceptional employer—Verdi becomes a pupil of Provesi—A painstaking copyist—Verdi wanted for a priest—Latin elements—Appointed organist of Roncole—A record salary—Barezzi's encouragement of Verdi's tastes—Father Seletti and Verdi's organ-playing—Provesi's status and friendship towards Verdi—Milan training for Verdi—Refused at the Conservatoire—Experience and training needed—Study under Vincenzo Lavigna of La Scala—Death of Provesi, and assumption of his Busseto duties by Verdi Page 16

[Pg viii]COURTSHIP, MARRIAGE, AND FIRST OPERATIC SUCCESS

Verdi is engaged class="csummary"to Margarita Barezzi—His marriage—Seeks a wider field in Milan—An emergency conductor—Conductor of the Milan Philharmonic Society—His first opera, Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio—Terms for production—Its success—A triple commission—A woman's sacrifice—Clouds—Death of his wife and children—Un Giorno di Regno produced—A failure—Verdi disgusted with music—Destroys Merelli contract—The Nabucco libretto forced on Verdi—Induced to set the book—Production of Nabucco with success—Opposition from the critics—Mr. Lumley gives Nabucco in London—Its performance and reception Page 27

SUCCESS, AND INTRODUCTION INTO ENGLAND

Verdi's position assured—Selected to compose an opera d'obbligo—The terms—I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata—Its dramatis personæ and argument—Reception at La Scala—A new triumph for Verdi—I Lombardi in London, 1846—Ernani—Political effect of Ernani—Official interference—Verdi first introduced into England—Mr. Lumley's production of Ernani at Her Majesty's Theatre—The reception of the opera—Criticism on Ernani—Athenæum and Ernani Page 49

FIRST PERIOD WORKS

I Due Foscari—Its argument—Failure of the opera in Rome, Paris, and London—Giovanna d'Arco—A moderate success—Alzira—Attila—More political enthusiasm—Attila given at Her Majesty's Theatre by Mr. Lumley—Its cool reception—The Times and Athenæum critics on Attila—Exceptional activity of Verdi—Macbeth—Jerusalem in Paris—I Masnadieri first given at Her Majesty's Theatre—Jenny Lind in its cast—Plot of the opera—The work a failure everywhere—The critics on I Masnadieri— Mr. Lumley offers Verdi the conductorship at Her Majesty's Theatre—Il Corsaro—La Battaglia di Legnano—Luisa Miller— Mr. Chorley on Luisa Miller—Its libretto—Reception of the work in Naples, London, and Paris Page 70

[Pg ix]RIGOLETTO TO AÏDA—SECOND PERIOD OPERAS

Turning-point in Verdi's career—The libretto of Rigoletto—Production of Rigoletto in Venice, London, and Paris—Great success of the opera—Athenæum and The Times on Rigoletto—"La Donna è mobile"—A second period style—Il Trovatore written for Rome—The libretto—Its reception at the Apollo Theatre—The work produced at the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden—Its cast, and Graziani's singing therein—Lightning study of the Azucena rôle—Athenæum and The Times on Il Trovatore—La Traviata—The libretto and argument—The first performance at Venice a fiasco—Judgment reversed—Brilliant success of the opera in London—Piccolomini's impersonation of Violetta—Mr. Lumley's testimony—The Press and La Traviata—Athenæum and The Times criticism of La Traviata—Les Vêpres Siciliennes—Prima donna runs away—Reception of the opera in Paris and London—Verdi in Germany—The Times criticism—Simon Boccanegra a failure—Un Ballo in Maschera—Trouble with the authorities—Production and success of Un Ballo in Maschera—Its reception in London—The Times on the opera—La Forza del Destino unsuccessful Page 104

[Pg x]REQUIEM MASS AND OTHER COMPOSITIONS

Verdi as a sacred music composer—Share in the "Rossini" mass—Failure of a patch-work effort—Missa de Requiem produced—Splendid reception—Performed at the Royal Albert Hall—Structure of the work—Von Bülow's opinion—Divided opinions on its style and merit—Its character—Modern Italian Church style—Northern versus Southern Church music—Verdi's early compositions—E minor Quartet for strings—L'Inno delle Nazioni—Its performance at Her Majesty's Theatre—Verdi's slender share in orchestral music—National temperament involved—Thematic method inconsistent with Italian national life Page 150

THIRD PERIOD OPERAS

A matured style—Methuselah of opera—The last link—Aïda—A higher art plane—Ismail Pacha commissions Aïda—Its libretto—Production at Cairo—The argument—Patti as Aïda—Athenæum criticism of Aïda—Otello—Scene in Milan—The initial cast—Its production and reception in London and Paris—Athenæum review of Otello—Its story—Vocal and instrumental qualities—Falstaff—A surprise defeated—Boito—Falstaff produced at La Scala—In France—Falstaff at Covent Garden—The comedy and its music—Athenæum opinion of Falstaff—A crowning triumph Page 167

[Pg xi]POLITICIAN AND CITIZEN

A born politician—Attempt to draw Verdi—The revolutionary ring of Verdi's music—Signor Basevi on this feature—National and political honours and distinctions—An inactive senator—England's neglect—The composer's nature and character—Bluntness of speech—A dissatisfied auditor—Verdi's alleged parsimony—Verdi and the curate—The gossips and his fortune—Life at St. Agata villa—An "eighty-two" word-portrait—Verdi's old-age vigour—Love of flowers—His hobby at the Genoa palazzo—Independence of character Page 203

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF STYLE

Verdi's popularity—An important personality in music—Most successful composer of the nineteenth century—Verdi's opportuneness—Keynote of future struck in Nabucco—Its characteristics—Distinguishing features of Verdi's music—Stereotyped pattern operas—Change of style imminent in Luisa Miller—Altered second period style of Rigoletto—This maintained in Il Trovatore—La Traviata forebodings—Basevi's charge of an altered style therein—La Traviata and débutantes—True Verdi style in Les Vêpres Siciliennes—Simon Boccanegra and Un Ballo in Maschera—Third period works—Aïda—Alleged Wagner influence—Mistaken criticism—Orchestration of Otello—Its style and technique compared with Aïda—Falstaff—Its position as an opera—A saviour of Italian art—The Illustrated London News defends Verdi from early critics—Later critics silenced—Verdi vindicated Page 223

[Pg xii]EFFECT UPON AND PLACE IN OPERA

Origin of opera—Melody in music—The first opera, Dafne—Monteverde's advances—Early opera orchestration—Gluck's reformed style in Orfeo and Alceste—A complete structure—Verdi's starting-point—Wagner's methods—Verdi's early operas—Don Carlos and an altered style—Its reception—A third or matured period method—Its characteristics—Aïda, Otello, and Falstaff—Verdi's disciples—Opera as a social need, past and present—Its reasonable decline—Verdi's ultimate position—His lasting works Page 273

VERDI LITERATURE

Its scantiness—Restricted scope for the writer and historian—English ideas of Italian opera—English books on Verdi—German historian's measure—Recent English press notices—Foreign journalistic criticism—Italian writings Page 293

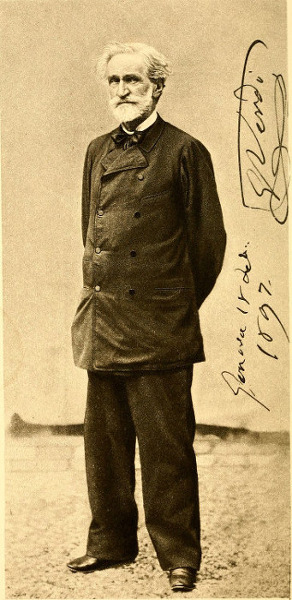

| Giuseppe Verdi | Frontispiece |

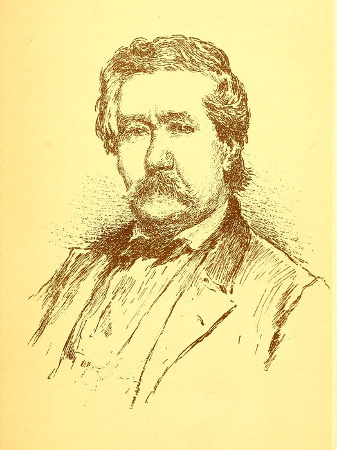

| Antonio Barezzi | Facing Page 14 |

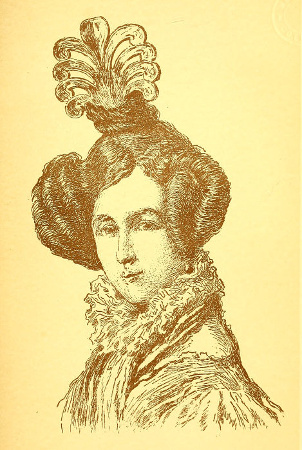

| Margherita Barezzi | Facing Page 40 |

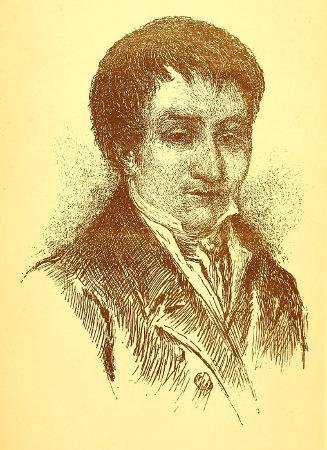

| Giovanni Provesi | Facing Page 160 |

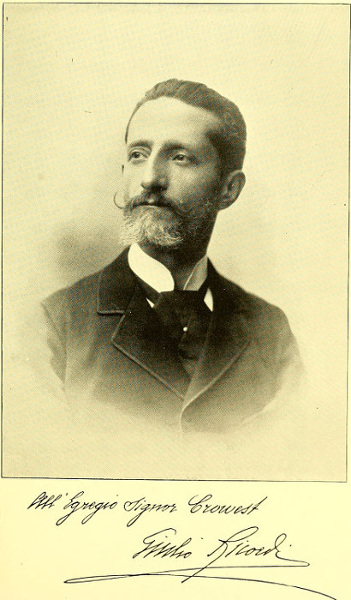

| Giulio Ricordi | Facing Page 216 |

This work is an attempt to tell, in a popular key, the story of Verdi's remarkable career. A connected chronological account of this composer's life is needed; and a plain unvarnished narrative will best coincide with the temperament and habit of one who, throughout a long life, has been singularly abhorrent of pomp and vanity.

In the literature concerning Verdi, the great man's English experiences have been studiously neglected. We learn about Verdi in Italy, also in France; but scarcely anything is recorded respecting Verdi in England—the land which, more than any other country, served to make and enrich Verdi. It is to show more of the English side of the famous maestro's career that the present book is written. It may, probably will be, long years ere Italy will have another such son to worship. A tone-worker like Verdi is rare. Then, few great composers who have appealed [Pg xiv] to the English public have lived to see their works received and appreciated to the extent that Verdi has; and it is unparalleled in the history of musical art, to find a musician, when a septuagenarian and octogenarian, giving to the world compositions which, for conception and freshness, far surpass the scores written by him in the vigour of middle age.

It would be ungracious indeed were I to neglect to express the very deep obligation which I am under to the illustrious maestro for the handsome and specially signed portrait which adorns this volume. Not less am I indebted to the Messrs. Ricordi for all the kind assistance and encouragement which they have afforded me during the preparation of this work.

F.J.C.

London, June 1897.

Verdi's birth and birth-place—Dispute as to his township—Baptismal certificate—His parentage—The parents' circumstances—The osteria kept by them—A regular market-man—A mixed business—Verdi's early surroundings and influences—Verdi not a musical wonder or show-child—His natural child-life—Enchanted with street organ—Quiet manner as a child—Acolyte at Roncole Church—Enraptured with the organ music—Is bought a spinet—Practises incessantly—Gratuitous spinet repairs—To school at Busseto—Slender board and curriculum—First musical instruction—An apt pupil.

Verdi was born at Roncole, an unpretentious settlement, sparsely inhabited, hard by Busseto, which, in its turn, is at the foot of the Appenine range, and some seventeen miles north-west of Parma, in Italy. The red-letter day, since such it deservedly is, on which this universal melodist first saw the light was the 10th October 1813. Terrible events shadowed his infancy. In 1814 the village was sacked by the invading allies. [Pg 2] Then the frightened women took refuge in the church—safe, as they believed, near the image of the Virgin—until the soldiers forced the doors, and slew women and children till the floor reeked with blood. One woman, with infant at breast, flew to the belfry and hid there, thus saving herself and her child. The child was the infant Verdi!

Whenever a son of man is born into the world who, in the mysterious course of events, turns out to be what mankind calls "great," there is inevitably a community jealous to claim ownership of the illustrious one, alive or dead. The subject may have lingered through troublous long seasons, craving vainly for the stimulus of even scanty recognition. He has only to become "great" to find hosts of persevering friends. Verdi having risen to great eminence, more than one locality has claimed him. He has been styled "il cigno di Busseto,"[1] and "il maestro Parmigiano"; but he was neither the swan of Busseto nor the master of the town of [Pg 3] cheeses. Roncole alone is entitled to the sonship of Verdi; and as both Parma and her smaller sister town, Busseto, have disputed his parentage, the point of interest has been very properly investigated. The result is that the question has been decided once and for all. A certificate written in Latin has been traced, which establishes beyond dispute both the time and place of Verdi's birth. The following is the text of the original document:—

"Anno Dom. 1813 die 11 Octobris—Ego Carolus Montanari Praepositus Runcularum baptizavi Infantem hodie vespere hora sexta natum ex Carolo Verdi qm Josepho et ex Aloisia Utini filia Caroli, hujus parocciae jugalibus, cui nomina imposui—Fortuninus Joseph, Franciscus—Patrini fuere Dominus Petrus Casali qd Felicis et Barbara Bersani filia Angioli, ambo hujus parocciae."

This dog Latin, translated into English, runs as follows:—"In the year of our Lord 1813, on the 11th day of October, I, Charles Montanari, placed in charge of Roncole, did at the sixth hour of this evening baptize the infant son of Charles Verdi and Louisa Utini, daughter of Charles, married in this parish, [Pg 4] under the name of Fortuninus Joseph Franciscus. The sponsors were Father Peter Casali qd Felicis and Barbara Bersani, daughter of Angiolus, both of this parish."[2]

The abode in which the infant Verdi first opened his eyes was one of the best known and most frequented among a cluster of cottages inhabited by labouring folk who found work and small wage in the immediate neighbourhood of Roncole, a three miles' stretch from Busseto. It was a tumble-down stone-and-mortar-mixture building of low pitch.

Padre Carlo Verdi and his good wife Luigia Utini were the licensed keepers of this small osteria, whereat wine, spirits, and malt, with their close relations pipes and tobacco, were matters of trade between Boniface or la signora and the frugal contadini who lived in and about Roncole. Wine and music! Another illustration of the curious union between harmony and alcohol—a connection which harmless as it really is, has been discouraged and taken fearfully to heart by a sensitive [Pg 5] sort of people, but which has never yet been satisfactorily disproved or accounted for by all the Good Templar philosophy. Bacchanalian aids were not the only commodities dealt in by the honest, though illiterate Carlo Verdi and his brave wife. The inn stood also as the local dépôt for such unromantic necessaries of existence as sugar, coffee, matches, oil, cheese, and sausage—all indispensable items in housekeeping, even in Italy.

The business air pervading the home of Verdi's childhood seems not to have affected his young mind, and, pecuniarily profitable as such an establishment for the sale of the liquids and solids of life may have been, the future musician does not appear to have shown any disposition towards becoming a vendor of unromantic necessaries or alcoholic unnecessaries of life. Happily, the fire of genius—the feu sacré—was in Verdi.

Verdi maggiore was distinctly a retail trader, running, with great good-nature, what are vulgarly known as "ticks" with the Roncolese. He went to market once a week, to buy in wholesale quantities grocery of one Antonio Barezzi, storekeeper, distiller, etc., [Pg 6] who, as circumstances proved, was to figure prominently in the Verdi dénouement.

It is a sorry reflection that several of our greatest musicians have had poverty and untoward circumstances as a "set off," as it would seem to be, for their bounteous musical gifts. A study of the lives of the great tone poets will reveal the saddening but not astonishing truth that, while the world's fairest minstrels have been shaping melodies and harmonies to gladden hearts and brighten homes for all ages, they themselves have frequently been enduring lives of misery, and sometimes want. Verdi at no part of his career has ever been in abject poverty, but his was by no means a luxurious early life, nor was his home particularly predisposed towards music. At first, there was not a pianoforte in it, nor can it be said that Verdi passed his childhood amongst surroundings to favour the muse, such as the paint pots, canvases, and stage lights upon which Weber's young imagination fed. The social and physical conditions in and around Busseto were ill calculated to inspire the mind with anything approaching the sublime or the ideal, the poetic or the beautiful; and there seemed to be insuperable difficulties [Pg 7] in the way of the son of the chandler's shopkeeper ever becoming a musician of any importance. But many most surprising episodes were to unfold themselves. This unpretentious spot of Italian soil was to prove the cradle of the revolutioniser of Italy's national music-drama. To-day it is incontrovertible that in Verdi's music, especially in his later writings, there is far more than could ever have been expected of any Italian master. His melody is the pure chastened current of the sunny South, and no one of his countrymen has written loftier operatic music than that in Aïda and Falstaff. Much of the flow and beauty throughout his compositions must, of course, be accounted for by the inability of any Italian son of art to compose else but luscious melody, while the life and gaiety, together with that irresistible "go" which so distinguish Verdi's tunes and colourings, may have borrowed their genesis out of the lively times and good humour that prevailed at that earliest home—the inn.

The unsophisticated Italian loves music much as a lark loves liberty, and it is not in Italy, as it used to be here, regarded as degrading to aspire to being a virtuoso. No [Pg 8] other occupation is so natural to the son of the South as music, and although Italians are keen business people when they once taste commercial success—even if it be of ice-cream born—yet they make better musicians. Verdi senior did not press his son into the service of Orpheus, and no steps appear to have been taken towards forcing the offspring into becoming a manipulator of chords and cadences. Young Verdi enjoyed a perfectly natural child-life, playing with children indoors and out of doors until he was old enough to be sent to school. He was no forced exotic.

There is a feature sometimes attaching to the lives of great musicians which, happily, in the case of Verdi does not require to be put forward. He proved no wonder-child or prodigy who—adroitly boomed—made the round of Europe with advantage financially and corresponding disadvantage musically. From the outset his career has been perfectly legitimate, and free from episodes or situations partaking of the supernatural—no circumstances presenting themselves to impede his quiet progress along the artistic way which he seems to have been content to travel.

What will he become? This is the question, pregnant with blissful uncertainty, which nearly every decent parent has to ask himself of a young hopeful. Doubtless Verdi senior applied the interrogatory to himself respecting Giuseppe, but it has not transpired that the subject of the inquiry furnished much solution to the problem, beyond the fact that he was always overcome when he heard street-organ music. No sooner did an organ-grinder appear in Roncole, with his instrument, than young Verdi became an attentive auditor, following the itinerant musician from door to door until fetched away. This was the first hint he gave of musical aptitude, and probably no one would have predicted that he would one day furnish melodies, almost without end, for these instruments of torture in each quarter of the globe. One particular favourite with little Verdi was a tottering violinist known as Bagasset, who used to play the fiddle much to the little fellow's delight. This obscure musician urged the osteria-keeper to make a musician of his son, and is said to have received many favours from the son since he became famous. The old itinerant, very grateful, used to exclaim, [Pg 10] "Ah! maestro, I saw you when you were very little; but now——!"

The Verdi who was to create such streams of sparkling melody, and need an Act of Parliament[3] to stop them, was a quiet thoughtful little fellow as a child, possessing none of that boisterous element common to boys. That serious expression seen in the composer's face, the first impression that a glance at any of his present-day portraits would convey, was there when a child. Intelligent, reserved, and quiet, everybody loved him.

Perhaps it was this good and melancholy temperament that attracted the attention of the parish priest, and which led to Verdi's receiving the appointment of acolyte at the village church of Le Roncole. He was now seven years old, and it was in connection with his office as "server" that we are introduced to the first episode, a really dramatic one, in his career. One day the ecclesiastic was celebrating the Mass with young Verdi as his assistant, but the boy, instead of following the service attentively with the priest, which no acolyte ever does, got so carried away by the [Pg 11] music that flowed from the organ that he forgot all else. "Water," whispered the priest to the acolyte, who did not respond; and, concluding that his request was not heard, the celebrant repeated the word "water." Still there was no response, when, turning round, he found the server gazing in wonderment at the organ! "Water," demanded the priest for the third time, at the same moment accompanying the order with such a violent and well-directed movement of the foot, that little Verdi was pitched headlong down the altar steps. In falling he struck his head, and had to be carried in an unconscious state to the vestry. A somewhat forcible music lesson!

Possibly it was this incident, and the child's unbounded delight at the organ music which he heard in the street, that set the father thinking of his son's musical possibilities, for at about this time, 1820, the innkeeper of Roncole added a spinet or pianoforte to his worldly possessions. This indispensable item of household belongings was purchased for the especial benefit of the boy-child, thus pointing to some indications of budding musical [Pg 12] aptness on his part. More soon followed! Young Verdi went to the instrument at all hours, early and late, playing scales and discovering chords and harmonious combinations. Sometimes he would forget or lose one of his favourite chords, and then there was an outburst of genuine native passion that stood in strange contrast to his usual quiet demeanour. A story goes that once, when he was labouring under one of these fits of temper, he seized a hammer and commenced belabouring the keyboard. The noise attracted the attention of his father, who stemmed his son's impetuosity with a sound box on the ears, which stopped the craze for pianoforte butchering. On the whole, however, every one was pleased with the little fellow's devotion to the instrument, and one friend went so far even as to repair it for him gratuitously, when it wanted new jacks, leathers, and pedals, which it soon did, owing to the boy's phenomenal wear and tear of the instrument. This spinet remained one of Verdi's most treasured possessions. It was stored at the villa at St. Agata, and no doubt has often recalled to the veteran's mind moments and feelings of his childhood. Inside it is an inscription, a testimonial creditable alike to the application [Pg 13] of the little musician as also to the goodness of the generous local tradesman, who, conscious, perhaps, of a future greatness for the child, had become one of his admirers. It runs: "I, Stephen Cavaletti, added these hammers (or jacks) anew, supplied them with leather, and fitted the pedals. These, together with the hammers, I give as a present for the industry which the boy Giuseppe Verdi evinces for learning to play the instrument; this is of itself reward enough to me for my trouble. Anno Domini 1821."

It was when he was about eight years of age that little Verdi's education became a subject for active consideration. His parents' deliberations ended in the resolve to send him to a school in Busseto. By virtue of an acquaintance with one Pugnatta, a cobbler, the future composer of the Trovatore and Falstaff was boarded, lodged, and tutored at the principal academical institution in Busseto, all at the not extravagant charge of threepence per diem! How this was managed history relateth not. Young Verdi's receptive faculties did not need to be severely extended, therefore, to spell "quits" to padre Verdi's generosity in the matter of letters and "keep" [Pg 14] for Giuseppe. After events abundantly prove that the little harmonist was not slothful in grappling the mysteries of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Whether, added to a fair knowledge of the three Rs, he, like most boys, made an acquaintance with another R, of pliable and impressive properties, is not known.

Concurrently with the scholastic training, Verdi's father provided some regular musical instruction for his son. The local organist of, and the greatest authority upon music in, Roncole was one Baistrocchi, and to him young Verdi was entrusted for the first training in music that he received. The terms for the music lessons were not extravagant, and were requited by a system of Dr. and Cr. account at the inn. Nevertheless, the instruction imparted was sound and solid, young Verdi proving smart at music. The measure of the musical merits of Baistrocchi has not transpired, and the world is uninformed as to whether he knew much, or little, musically; but whatever store of harmonious erudition was possessed by him he poured into his young charge. At the end of twelve months Baistrocchi felt bound to confess that Verdi [Pg 15] knew all that he had to teach him. Thus, either the teacher had an unusually small store of information to impart, or the student possessed an abnormal appetite for musical learning.

[1] Rossini used to be styled the "Swan of Pesaro," but in his old age he laughed at this compliment, and endorsed a Mass which he had composed as the work of "the old Ape of Pesaro," thus parodying the "swan" or cigno sobriquet which had been given him.

[2] There is in existence another Certificate of this musician's birth. This is in the Registry of the État Civile of the Commune of Busseto for the year 1813, and is written in French, Italy being at the time under French rule.

[3] Mr. Michael T. Bass, M.P., "Bill for the Better Regulation of Street Music in the Metropolitan Police District."

Verdi goes into the world—Office-boy in Barezzi's establishment—Congenial surroundings—An exceptional employer—Verdi becomes a pupil of Provesi—A painstaking copyist—Verdi wanted for a priest—Latin elements—Appointed organist of Roncole—A record salary—Barezzi's encouragement of Verdi's tastes—Father Seletti and Verdi's organ-playing—Provesi's status and friendship towards Verdi—Milan training for Verdi—Refused at the Conservatoire—Experience and training needed—Study under Vincenzo Lavigna of La Scala—Death of Provesi, and assumption of his Busseto duties by Verdi.

When ten years of age, Verdi went into the world. Could the parent have foreseen the future that lay in store for his boy, he might have given him a little more learning, and have risked being a little the poorer. He saw nothing, however. His child had been to school, and could read, write, and add figures—an ample education for the son of a poor locandiere! Beside which the parents at no time entertained any greater musical [Pg 17] ambition than that their boy might, one day, become organist of the village church!

When the industrious parent used to trudge from Roncole to Busseto to replenish the "general" department of his business, it was to purchase from the wholesale grocer's store which, as we have seen, was presided over by Antonio Barezzi. It was a flourishing concern, and its owner was a fairly rich man. What was worth more than his money, however, was a good disposition and kindliness which endeared him to his traders. Verdi senior was an especially welcome visitor. With him the storekeeper gossiped, the conversation turning betimes upon the little fellow at home and his budding musical tendencies. Music and culture, it should be stated, were dear to Barezzi, and had placed him at the head of everything musical in Busseto. Thus he was President of the local Philharmonic Society, for which he held open house for rehearsals and meetings. Barezzi's instrumental ability was considerable, and he could perform on the flute, clarionet, French horn, and ophicleide.

As luck would have it, young Verdi was to be thrown into the service of this Barezzi. In the course of their gossipings, innkeeper had [Pg 18] hinted to merchant that the son would have to be bestirring himself; and Barezzi, having a vacancy for an office-boy, offered to try Giuseppe. The matter was speedily arranged, and the boy soon proved that he could make himself useful to Barezzi—merchant in spirits, drugs, drysaltery, and spices.

The average business man views a predilection for music, or indeed for any art study, as fatal to duty and discipline. Not so Barezzi. He encouraged the musical proclivities of the office-boy, and, as we shall discover, most generously and materially assisted him towards an inevitable artist career. In time he began to regard Verdi as one of his family, and allowed him the use of the pianoforte.

Let us see what happened. Without neglecting his daily duties in the office, young Verdi availed himself of every moment of spare time to add to his musical knowledge and practice. He seldom missed an opportunity of attending the rehearsals held in Barezzi's house, or the public concerts given by the Philharmonic Society under the conductorship of Giovanni Provesi, organist and bandmaster of the duomo of Busseto. In return Verdi copied the instrumental [Pg 19] parts for the various performers, working at "string" and "brass" parts with a neatness and accuracy that quite won the hearts of those who had to play therefrom. Some people would declare such copying to be inconceivable drudgery, but young Verdi relished the excellent insight into orchestration which such practice afforded him. Provesi, on his part, was so pleased that he gave the lad some gratuitous instruction, of which Verdi took such advantage that at the end of two or three years the master frankly owned, like Baistrocchi, that the pupil knew as much as he himself did.

No wonder that Provesi, struck with the lad's musical promise, one day advised him to think of music as a profession. It so happened, however, that the lad just then was dangerously near to becoming a knight of the cowl instead of the bâton. The priests had got hold of him, and one ecclesiastic, Seletti by name, had commenced to teach him the Latin tongue, with the view, some day, of making a priest of him! Thus Verdi might have been for ever meditating in the cloister, instead of ministering to great demands, choreographic and otherwise, of a modern [Pg 20] lyric drama stage! "What do you want to study music for?" said the priest, at the same time backing up the query with the not very comforting nor accurately prophetic warning that he would "never become organist of Busseto"—a position which he did subsequently fill. "You have a gift for Latin, and must be a priest," was the confessor's parting shot.

Now the organist of Roncole died, creating a vacancy. Officialism and bumbledom, usually connected with organ elections, did not operate here. All concerned were agreed that, although young, the son of townsman Verdi was musically and morally fitted for the post, and he was thereto appointed. The salary was not overpowering, the exact payment being £1:12s. yearly! Thus the parents' wish was gratified, for their little son was duly appointed in Baistrocchi's stead, and from his eleventh to his eighteenth year Verdi performed his duties in the dusty old organ-loft at Roncole, supplementing his salary with small fees for such additional services as baptisms, marriages, and funerals. Every Sunday and Feast-day he trudged on foot from Busseto to Roncole to perform his [Pg 21] duties. Sometimes it was scarcely daybreak, and on one of these excursions he fell into a ditch, and would assuredly have been drowned, or frozen to death, save for the timely aid of a peasant woman, who had heard his groans.

How long Verdi remained in the employ of Barezzi has not transpired, but important subsequent events prove that he retained the friendship and esteem of the merchant long after being released of the tedium of bills and quantities calculations. He continued to receive musical training from Provesi until he was sixteen years of age, and it is not improbable that his generous employer, observing the musical inclinations of his clerk, allowed him to drift naturally into a harmonious haven. A story told of the young musician this while is ominous. It came to pass that Father Seletti, who would have the born-opera-composer a monk, was officiating at mass on an occasion when Verdi happened to be deputizing at the Busseto organ. Struck with the unusually beautiful organ music, the priest at the close of the service expressed a desire to see the organist. Behold his amazement on discovering his scholar whom he had been seeking to estrange from harmony to theology! [Pg 22] "Whose music were you playing?" inquired Seletti. "It was beautiful." Verdi, feeling shy, informed the priest that he had brought no music with him, and had been improvising. "So I played as I felt," he added. "Ah!" exclaimed Seletti, "I advised you wrongly. You must be no priest, but a musician."

Provesi had an extensive musical practice in and around Busseto, to which he gradually introduced Verdi. More and more frequently he deputized for Provesi, and the sight must have been worth seeing, of the diminutive organist, fifteen years old, on the high seat in the great organ-loft in the dim cathedral of Busseto—all unconscious, as every one else was, of the great future before him. When, from advancing years, Provesi resigned the conductorship of the Philharmonic Society of the town, Verdi was unanimously selected for the vacancy. His chief delight was to compose pieces for the Society and to perform them. These early compositions are preserved among the archives of Busseto.

The master musician is not an easily moulded quantity. He has first to traverse the whole surface of musical science; even then, [Pg 23] Nature may have denied to him those gifts of colour and glow which are the wings of music, and lacking which, he may remain for ever a mathematical musical machine, too many of whom, loaded with academical degrees and distinctions, and the consequent array of scholastic millinery, have been given to the world.

Verdi's ambition was to become a successful opera composer, but ere he could succeed, there were branches of study which could only be mastered in an establishment such as the Conservatoire at Milan. To it Verdi's friends, notably Provesi (who prophesied that one day Verdi would become a great master), urged him to go. There was one undeniable obstacle—the money! This difficulty was, however, eventually overcome. One of the Busseto institutions was the "Monte de Pieta," which granted premiums to assist promising students in prosecuting their studies. Verdi's petition was sent up, and with the wheels of benevolent machinery turning, as usual, slowly, the decision was long delayed. At this crisis stepped in Barezzi, grocer and gentleman, as he proved, who agreed to advance the money, pending the decision of [Pg 24] the institution. This enabled Verdi to turn his face towards Milan. He did not forget the kindness, but returned Barezzi the money, in full, from the first savings he was able to make from his art.

It is a grim commentary upon the usual way of managing the things of this life, to witness a man who has made melody for the whole world for now over half a century being refused an entrance scholarship at the training institution of his own land! It is a fact, nevertheless, that Verdi was actually denied admittance to the Conservatoire di Musica of Milan, on the ground of his showing no special aptitude for music! Yet the world goes on, gaping and wondering at its monotonous mediocrity, while seven-eighths of its energy is being exhausted in repairing the consequences of the genius of its blunderers, who somehow are generally and everywhere in power, and rampant. Chiefly from shame, the rejection of Verdi at the Conservatoire has been industriously excused, but the mistake shall always stand to the discredit of Francesco Basili, the then Principal. Men like Verdi—men of metal—may be hindered, but are rarely defeated by obstacles, or long-refused [Pg 25] justice. Verdi had fixed his heart and eyes on a mark which he has never left, and in this respect, if in no other, he is a model for every earnest struggling student.

Verdi had now to look elsewhere for that training which he had hoped to obtain at Milan. "Think no more about the Conservatoire," said his friend Rolla to him. "Choose a master in the town; I recommend Lavigna."

Vincenzo Lavigna was an excellent musician, and conductor at the theatre of La Scala. To him, accordingly, Verdi went for practical stage experience and familiarity with dramatic art principles. This was in 1831, when the pupil was eighteen years old. Lavigna could not have desired a more exemplary pupil than Verdi was, and the master lost no time before taking his charge into the broad expanse of practical theatre work. All the drudgery of harmony, counterpoint and composition generally, had been learned and committed to heart long before; it was practice and experience in the higher grades of planning and spacing libretti, and the scoring of scenas and concerted numbers for operas, that Verdi needed. This Lavigna could and did give him. Verdi, on his part, showed such aptitude [Pg 26] for dramatic composition that Lavigna was greatly pleased. "He is a fine fellow," said Lavigna to Signor Barezzi, who had called to inquire as to the progress of his protégé; "Giuseppe is prudent, studious, and intelligent, and some day will do honour to myself and to our country."

The death, in 1833, of Provesi, the guiding musical spirit of Busseto, meant another episode in Verdi's career. By the conditions of the loan from the trustees of the "Monte di Pieta" of Busseto, he was to return home from Milan to take up Provesi's duties. Such a heritage of work, including the post of organist at the duomo, the conductorship of the Musical Society of Busseto, much private teaching, etc., kept Verdi well employed; but it did not deter him from a regular and assiduous prosecution of his operatic studies. He worked with an almost unbounded will and pride in Busseto. Why? Because there was present there a power which fired him with enthusiasm and ambition; otherwise the call from Milan might have been a difficult step for him to take; one word, however, will explain all—Verdi was in love!

Verdi is engaged to Margarita Barezzi—His marriage—Seeks a wider field in Milan—An emergency conductor—Conductor of the Milan Philharmonic Society—His first opera, Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio—Terms for production—Its success—A triple commission—A woman's sacrifice—Clouds—Death of his wife and children—Un Giorno di Regno produced—A failure—Verdi disgusted with music—Destroys Merelli contract—The Nabucco libretto forced on Verdi—Induced to set the book—Production of Nabucco with success—Opposition from the critics—Mr. Lumley gives Nabucco in London—Its performance and reception.

When Verdi took the office stool in Barezzi's counting-house, there was little reason to suppose that he would get much beyond it; but he was to become something more than an employé. He was often invited to join the family circle, and so became acquainted with the eldest daughter, Margarita—a girl of beautiful disposition, with whom Verdi fell violently in love. The young lady returned his affection, [Pg 28] and Signor Barezzi, with his usual kindly feeling towards Verdi, not opposing the engagement—albeit Verdi was extremely poor—the young people were married in 1836. Upon this occasion all Busseto turned out en fête.

Now had Verdi every incentive to work, for his young wife bore him a son and a daughter within two years of their marriage, and he longed for an operatic success that would add to his slender income. The prospect of a large family, and no means to support it with, was a painful piece of mathematics, the solution of which depended entirely upon himself. Alas! could he but have foreseen his almost immediate release from such love chains!

While thus musing, the fire kindled. Verdi made up his mind to relinquish working in Busseto and try his fortune in Milan. Accordingly, in 1838, he, with his wife and children, set out for that musical centre, carrying their belongings with them, and with his stock-in-trade—a score of a musical melodrama entitled Oberto, Conte di S. Bonifacio—under his arm. This composition was [Pg 29] his first attempt at a complete opera. Every pain had been taken with the score; and not only was each note Verdi's own, but the full score, and all the vocal and instrumental parts, had been copied out with his own hand. What labour! and yet the hard (we might say thick) headed man rejoices in the belief that musicians, big and little, are a lazy lot!

None too speedily, an opening presented itself at the Milan Philharmonic Society. Haydn's Creation was to be given, and the conductor had failed to put in an appearance. Suddenly Verdi was espied, whereupon Masini, a director, approached and begged him to take the conductorship that evening. In those days conducting was managed, not with a bâton and a rostrum, but from the pianoforte in the orchestra, and Masini considerately informed Verdi that if he would play the bass part merely, even that would be sufficient! Verdi acquiesced, and, amid starings and titterings, made for the conductor's seat and score. "I shall never forget," Verdi has said, "the sort of sarcastic approval that crossed the faces of the knowing ones. My young, thin, and shabbily-attired person was little calculated, perhaps, to inspire confidence." Yet Verdi [Pg 30] astonished everybody. He gave not only the bass line, but the whole of the pianoforte part, bringing the performance to a successful termination. Not from that night need he have been without an appointment as a musical conductor; indeed, it was shortly afterwards that the conductorship of the Milan Philharmonic Society was offered to, and accepted by Verdi.

Possessed almost by the demon of the stage, Verdi sorely wanted a trial for his opera. To obtain a first hearing then, however, meant the surmounting of considerable obstacles. The avenues of art were not open as they now are—when a season is made up almost wholly of "first nights," and when wealthy or well-backed aspirants can have, not only their own theatres, but their own critics, and even their own newspapers and audiences. Such is money! Eventually Verdi got what he wanted. Oberto, Conte di S. Bonifacio was to be produced at La Scala theatre in the spring of 1839; but even this arrangement was put off because a singer fell ill. Sick at heart, Verdi was retreating to Busseto, when the impresario of La Scala sent for him unexpectedly. Signor Bartolomeo Merelli had heard from the singers who had been studying [Pg 31]Oberto respecting the uncommon quality of its music, and the opinions of the vocalists Signora Strepponi and Signor Ronconi were not to be lightly regarded. The outcome of the interview was an agreement by which Verdi's opera was to be put upon the stage during the next season at Merelli's expense—Verdi in the meanwhile making certain alterations in the score, chiefly because of a change of artists from those for whom it was originally written. Merelli was to divide with Verdi any sum for which the score might be sold, in the event of the opera proving a success. He jumped at the offer, for in those days the fashion was for impresarii to demand, and to receive, large sums from unknown composers wishing to have their operas brought forward. Tempora mutantur. Nowadays the difficulty with managers is to find the talent! Oberto was duly produced on the 17th November 1839, the principal singers being Mesdames Raineri-Marini, and Alfred Shaw, while Signori Salvi and Marini filled the tenor and bass parts respectively. The opera saw several representations, and a further proof of its merit is seen in the fact that music-publisher Ricordi [Pg 32] gave Verdi two thousand Austrian liri, or about £70 sterling, for the copyright of the work.

Verdi's next experience was a commission. Shortly after the production of Oberto, impresario Merelli, who "ran" the Milan and Vienna opera-houses, approached Verdi respecting the composition of three operas—one every eight months, for the sum of £134 for each opera, with an equal division of any amount arising from the sale of the copyrights.

This contract came opportunely, for Verdi was on the verge of appealing to his father-in-law for a £10 loan wherewith to pay rent overdue for his modest apartment. Now, Merelli was asked to make an advance, "on account," but he would not. Weak and dispirited after a long illness, Verdi was greatly distressed at the thought of failing to meet his rent. Here, however, came man's blessed balm when desperate moments face him—in the womanly unselfishness of a brave wife. Seeing her husband's anxiety, Signora Verdi collected her trinkets, went out and raised money upon them, bringing it all to Verdi. "How she managed it," related Verdi afterwards, "I know not; but [Pg 33] such an act of affection went to my heart. I resolved not to rest until I had got back every article, and restored it to the dear one."

Cloud and sunshine, these are the alternating portions of the mortal's lot. No sooner did Verdi begin to feel easier at the prospect of earning some four hundred pounds by these three operas than his home was suddenly darkened. With the swiftness of a rushing avalanche all that was brightest in his home was swept away. Ere he could realise it, he had lost his wife, son, and daughter. Verdi tells the terrible story as only the sufferer himself can. "My bambino (little boy) fell ill early in April (1840), and the doctors failing to discover the mischief, the poor little fellow got weaker and weaker, and passed away finally in the arms of his mother. She was heart-broken. Immediately our little daughter was seized with an illness which also terminated fatally. This was not all. At the beginning of June my dear wife was cast down with brain fever, until, on the 19th, a third corpse was borne from my house. Alone! alone! In a little over two months three coffins, all that I loved and cherished most on earth, [Pg 34] were taken from me. I had no longer a family!"

Here was room for grief. What a situation for one tied by an agreement to compose a comic opera, the score of which was already overdue! It was impossible. Yet bills were flowing in, and to meet these Verdi must, despite all terrible anguish, fulfil his engagement. He did. Among the libretti which Merelli had submitted was one renamed Un Giorno di Regno. This Verdi set to music. It was produced at La Scala Theatre on the 5th September following his wife's death, and was a failure. No wonder that Verdi desponded, and begged of Merelli that he would cancel the agreement, which he did, tearing the document to pieces. Verdi's resolute intention was never to compose another note! Ah! By some force of fate Verdi, many weeks afterwards, quite by accident, stumbled across Merelli, and although the composer was still obdurate, ere the two parted a libretto by Solera was forced into Verdi's coat-pocket, upon the chance, as Merelli put it, of his looking at and being tempted to set the book.

Strange to say, this "Nebuchadnezzar" [Pg 35] libretto took hold of Verdi. Arriving home, the composer tossed the manuscript on to the table. It opened of itself at a truly felicitous passage, "Fly, O thought, on golden wings," which so interested Verdi that he read on. Finally, the whole poem was in his mind, and so disturbed his rest that he determined to return the book next day to Merelli. The impresario would not have it, and told him to take the libretto away and keep it until he could find the will to set it.

Nabucco was replete with beautiful passages, which, one by one, were set by Verdi, until, in the autumn of 1841, the entire opera was finished. Two stipulations Verdi now insisted upon. Signora Strepponi and Signor Ronconi were to sing in Nabucco, and the work was to be produced during the Carnival time. Merelli declared he could not manage the scenery in the time; but Verdi would not hear of waiting for new scenery, and consenting to risk the production with whatever chance canvas the resources of the theatre supplied, Nabucco found its way into La Scala bills for the 1842 season.

The opera was given on 9th March, and both Signora Strepponi and Signor Ronconi sang in it.

"With this score," subsequently related Verdi to Signor Giulio Ricordi, "my musical career really began. With all impediments and difficulties Nabucco was undoubtedly born under a lucky star. All that might have been against it proved in its favour. It is a wonder that Merelli did not send me and my opera to the devil, after the furious letter which I sent him. The second-hand costumes, made to look equal to new, were splendid, while the old scenery, renovated by Perrani, might have been painted for the occasion."

Nabucco took everybody by surprise. It was a species of melodic vein and choral combination that the Milanese dilettanti had never before heard; such instrumentation, too; such novel and impressive effects were not within the memory of the oldest habitué of La Scala. The Italians could not resist its peculiar "carrying-along" power. The work was unanimously declared the true ideal of what a tragic musical drama should be. Little wonder that during its rehearsals the workmen stopped to listen to the music of the new piece. Many years afterwards, in his success, Verdi referred to this incident in sympathetic words:——

"Ah!" said Verdi, "the people have [Pg 37] always been my best friends, from the very beginning. It was a handful of carpenters who gave me my first real assurance of success."

I scented a story, and asked for details.

"It was after I had dragged on in poverty and disappointment for a long time in Busseto, and had been laughed at by all the publishers, and shown to the door by all the impresarios. I had lost all real confidence and courage, but through sheer obstinacy I succeeded in getting commonly contracted in Italy—rehearsed at the Scala in Milan. The artistes were singing as badly as they knew how, and the orchestra seemed bent only on drowning the noise of the workmen who were busy making alterations in the building. Presently the chorus began to sing, as carelessly as before, the 'Va, pensiero,' but before they had got through half a dozen bars the theatre was as still as a church. The men had left off their work one by one, and there they were sitting about on the ladders and scaffolding, listening! When the number was finished, they broke out into the noisiest applause I have ever heard, crying 'Bravo, bravo, viva il maestro!' [Pg 38] and beating on the woodwork with their tools. Then I knew what the future had in store for me."[4]

Some idea of the novel character of the Nabucco music may be gathered from the discovery that the usual chorus of La Scala was adjudged too small to give effect to it. Merelli, apprised of this, would not hear of increasing the staff because of the expense. Then a friend volunteered the extra cost. "No, no!" thundered in Verdi. "The chorus must be increased. It is indispensable. I will pay the extra singers myself." And he did! The success of Nabucco was remarkable. No such "first night" had marked La Scala for many years, the occupants of the stalls and pit rising to their feet out of sheer enthusiasm when they first heard the music. "I hoped for a success," said Verdi; "but such a success—never!"

The next day all Italy talked of Verdi. Donizetti, whose melodious wealth had swayed the Italians, as it subsequently did the English, was among the astonished ones. He had deferred a journey in order to hear Nabucco, [Pg 39] and was so impressed by it, that nought but the expressions; "It's fine! Uncommonly fine!" could be heard escaping his lips. With Nabucco the impressionable Italians were agreeably warned that a master-mind was amongst them.

Verdi sold the score of Nabucco to Ricordi for 3000 Austrian liri, or £102, of which, by the terms of the contract, Merelli the impresario was to share one half. He generously returned Verdi 1000 liri.

In the year 1846 Nabucco was brought to London. Mr. Benjamin Lumley elected to open the season with it. Her Majesty's theatre had been newly painted and embellished, and all London was on the tiptoe of excitement at the prospect of the inauguration of the new salle. No more striking novelty than Nabucco could have been selected, perhaps, since the work had already become popular on the Continent, and had in some places created a furore. The English public, it should be stated, already knew Verdi through Ernani, which opera, as the reader will learn later on, had been performed in London the previous year, and had startled the susceptibilities of our critics. The object in presenting this Nabucco by Verdi was [Pg 40] to afford the public an opportunity of a further judgment upon the ear-arresting composer of Ernani. In obedience to a prevalent sentiment precluding the slightest connection of a Biblical subject with stage representation, Nabucco had to be rechristened. It received the alias "Nino, Re d'Assyria," and was brought forward.

"In a popular sense," writes Mr. Lumley, "the opera was a decided success; the choral melodies especially suiting the public taste. The libretto, although faulty in many respects, was dramatic, and afforded scope for fine acting and artistic emotion. Nabucco, in short, floated on the sea of the Anglo-Italian stage where, whilst one current was always rushing towards novelty, another tended to wreck all novelty whatever, in the interests of so-called 'classicism.' Much had been done to place the opera with splendour on the stage, but though it pleased on the whole, no decided success attended the venture of the two new ladies. Sanchioli, wild, vehement, and somewhat coarse, attracted and excited by her 'power, spirit, and fire,' but she failed to charm. As a 'declaiming, passionate vocalist' she created an effect; but the very qualities [Pg 41] which had rendered her so popular with an Italian audience, acted somewhat repulsively upon English opera-goers. The lack of refinement in her style was not, in their eyes, redeemed by the merit of energy. The electric impulse that communicated itself to the Italians, fell comparatively powerless on the British temperament. Sanchioli, however, was in many respects the 'right woman in the right place' in this melodramatic opera. The other lady, Mademoiselle Corbari, though destined in after times to please greatly as an altra-prima on the Anglo-Italian stage, and though she was considered from the first charming, even 'fascinating' in her simplicity and grace, was not yet acknowledged as a leading vocalist. The nervousness and inexperience of a novice, which she showed at that stage of her career, somewhat lessened the success due to a sweet voice and feeling style, though the prayer allotted to her character Fenena, was encored nightly. Fornasari pleased those who remained of his old enthusiastic admirers, by his emphatic dramatic action and vigorous declamation, and thus far worked towards the success of Verdi's opera." [5]

The libretto of Nino or Nabucco is based upon the history of the Assyrians and Babylonians at the epoch when these two nations were distinct. Ninus, the son of Belus, the first Assyrian monarch, is engaged in exterminating the Babylonians. He profanes their temple, insults their faith, and finally falls a victim to the vengeance of Isis. He goes mad. His supposed daughter, Abigail, obtains possession of the kingdom, to the exclusion of his lawful heiress, Fenena, who is about to be sacrificed with the Babylonians, whose faith she has embraced, when Ninus, repenting of his evil deeds, recovers his reason in time to save her from death, and the drama winds up with the submission of the proud monarch and his whole court to Isis.

"This opera," wrote a capable critic at the time, "the first by which the young composer achieved his exalted reputation, and which has been received abroad with enthusiasm, is a most remarkable work. It is characterised by merits of the highest order. This is shown in the splendid finale of the first act, commencing with the charming terzettino which has been for some time already a [Pg 43] favourite with English dilettanti; the canon preceding the punishment of Nino, in the second act; the duet 'Oh! di qual onta' between the latter and Abigail in the third act, in which the voices are made to combine in the most exquisite manner; the charming chorus, 'Va, pensiero,' flowing and plaintive; and the final prayer 'Terribil Iside,' sung without instrumental accompaniment. These morceaux require to be studied in detail for their beauties to be fully appreciated; but they nevertheless produce, at first hearing, an effect which pieces abounding, as they do, in imagination and remarkable excellence of construction, do not always obtain. They are more highly characteristic. The opening chorus, 'Gli arredi festivi giu cadono infranti,' is severe and characteristic, and altogether peculiar in its construction. The first aria of Orotaspe is very remarkable in point of composition. The first part of the solo of Abigail, which is much admired, did not produce at first hearing any deep impression on ourselves; the second part is very good, and characteristic of the vengeful Amazon. The prayer for soprano at the end of the opera, 'Oh, dischinso e il firmamento,' [Pg 44] is a charming little bit of melody. In fine, in the music of the opera the composer has shown himself possessed of all the legitimate sources of success. It bears the stamp of genius and deep thought, and its effect upon the public proved that its merits were appreciated." [6]

This favourable view, however, was far from being endorsed by all the leading critics—inasmuch as it was with Nino that Verdi experienced more of his early and remarkable castigations in the English press.

Henry Fothergill Chorley, English musician, art critic, novelist, verse writer, journalist, dramatist, general writer, traveller, etc., was musical critic of the Athenæum from 1833 to 1871, a period which covers Verdi's career down to the production of Aïda, and it is fair to assume, therefore, that the contributions, signed and unsigned, which appeared in the Athenæum were the views and expressions of that gentleman—deceased. James William Davison, English composer and writer (1813-1885), was musical critic of The Times to the day of his death, so that that gentleman, also deceased, may be credited with the emanations [Pg 45] respecting Verdi and his doings which appeared in its columns. Now, when Nabucco, in its Anglicised form as Nino, was produced here, the former critic wrote: "Our first hearing of the Nino has done nothing to change our judgment of the limited nature of Signor Verdi's resources.... Signor Verdi is 'nothing if not noisy,' and by perpetually putting his energies in one and the same direction, tempts us, out of contradiction, to long for the sweetest piece of sickliness which Paisiello put forth.... He has hitherto shown no power as a melodist. Neither in Ernani nor in I Lombardi, nor in the work introduced on Tuesday (Nino) is there a single air of which the ear will not lose hold.... The composer's music becomes almost intolerable owing to his immoderate employment of brass instruments, which, to be in any respect sufferable, calls for great compensating force and richness in the stringed quartette.... How long Signor Verdi's reputation will last seems to us very questionable."[7] Of these remarks we would say that Verdi and his reputation both live to-day!

It need hardly be pointed out that the [Pg 46] critical faculty in its perspicacity and highest degree are wholly wanting in this criticism. Verdi has shown himself to be a born melodist; his reputation for his melodies has been great and world-wide, even those of such early operas as Ernani and I Lombardi are still with us—to wit, that lovely excerpt "Come poteva un angelo" from the latter work; while the orchestral excessiveness charged to him, thus early, was just the thing for which thirty years later, when Aïda was produced, he was by many musical minds declared to be indebted to Wagner, and abused consequently.

The Times criticism on Nino was less despairing. "The melodies" (we were told) "are not remarkable, but the rich instrumentation, and the effective massing of the voices do not fail to produce their impression, and a 'run' for some time may be confidently predicted."[8]

Mr. Lumley revived Nino (Nabucco) towards the close of his memorable and vicissitudinous management. It was during the 1857 season. Mademoiselle Spezia made a decided mark in the part of Abigail, but the [Pg 47] object of interest was Signor Corsi, who made his début on the occasion.

"This celebrated singer," Mr. Lumley informs us, "had acquired so high a reputation in Italy as the legitimate successor to Georgio Ronconi, in the execution of lyrical parts of dramatic power, that the liveliest curiosity was excited by his first appearance."[9] Signor Corsi failed, however, to establish his claim to public favour either as a singer or actor. Curiously enough, this same season witnessed the production of the work under the name of Anato by the rival London opera company, under Mr. Gye, at the Lyceum Theatre.

Nowadays we hear little of Nabucco. The world can well afford to go on with one opera the less, even though it be a good one; but fifty years have worked a vast change in operatic values, and, although the revival of Nabucco might not be called for now, it must not be forgotten that, when it first appeared, it was, as an able critic has put it, "almost the only specimen the operatic stage has of late years furnished of a true ideal of the tragic drama."[10]

Much that Nabucco contained demonstrated the fully-trained composer, the scientific musician, and the able contrapuntist. The splendid chorus "Gli arredi festivi," sung by all the voices, and taken up by the basses alone; the charming chorus of virgins, "Gran Nume," beginning pianissimo and swelling up to a glorious burst of harmony; and the grand crescendo chorus Deh! l'empri, these manifested indisputable originality and learning. Other notable numbers proved to be the chorus "Lo vedesti," and the "Il maledetto non ha fratelli" movement; while the canone for five voices, "Suppressau gi'istanti," the scena, "O mia figlia" (which Fornasari was wont to render so feelingly), and the duet "Oh di qual onta aggravesi," are remarkable examples of characteristic musical composition, sure indications of greater artistic triumphs by their author. Among the many orchestral points of Nabucco, the harp accompaniment in the Virgins' chorus, and the employment of the brass instruments in the great crescendos are particularly novel and effective. Little wonder that such a work struck the keynote to Verdi's future greatness.

[4] Dr. Villiers Stanford in The Daily Graphic, 14th January 1893.

[5] Reminiscences of the Opera, p. 145 (Lumley).

[6] Illustrated London News, 14th March 1846.

[7] Athenæum, 7th March 1846.

[8] The Times, 4th March 1846.

[9] Reminiscences of the Opera, p. 416.

[10] Musical Recollections of the last Half-Century (1850 Season), May 31.

Verdi's position assured—Selected to compose an opera d'obbligo—The terms—I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata—Its dramatis personæ and argument—Reception at La Scala—A new triumph for Verdi—I Lombardi in London, 1846—Ernani—Political effect of Ernani—Official interference—Verdi first introduced into England—Mr. Lumley's production of Ernani at Her Majesty's Theatre—The reception of the opera—Criticism on Ernani—Athenæum and Ernani.

Now, at the age of twenty-nine years, was Verdi's future practically assured. His ambition had been to produce an opera that would win the applause of his countrymen. This was attained sooner, perhaps, than Verdi expected it. With this desire more than fulfilled, the son of the obscure innkeeper of Roncole was being talked of in the same breath as the maestri Donizetti, Mercadante, and Pacini. Would that his beloved wife and children could have been with him to have shared this success!

A great honour was now to be his. By the vote of the La Scala Theatre direction, Verdi was chosen to be the composer of the opera d'obbligo for the Carnival time—that new opera which an impresario is bound, by the terms of his agreement with the municipality, to find and produce during each season. Merelli conveyed the news to Verdi, tendering him a blank agreement form and saying, "Fill it up; all that you require will be carried out."

Verdi consulted Signora Giuseppina Strepponi, the young and attractive tragédienne who had performed so admirably as Abigail in Nabucco (she afterwards became Madame Verdi). Her advice to the composer was to "look out for himself," but to be reasonable, suggesting similar terms to those paid to Bellini for Norma. Verdi asked, therefore, eight thousand Austrian liri (£272 sterling), and the bargain was struck.

Within eleven months Verdi was on La Scala boards with his fourth opera, a work which deserves lengthy notice because of the hold it has always had over English audiences. Signor Solera had prepared what, from an Italian point of view, was an excellent libretto, [Pg 51] based upon a poem by Grossi, covering the epoch of the First Crusade. The dramatis personæ of I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata ran:

Pagano, Arvino, sons of Pholio, the Prince of Rhodes; Viclinda, wife of Arvino; Griselda, daughter of Arvino; Acciano, tyrant of Antioch; Sofia, his wife; Oronte, his son; Prior of the city of Milan; Pirro, armour-bearer to Arvino; monks, priors, people, armour-bearers, Persian ambassadors, Medes, Damascenes, and Chaldeans, warriors, crusaders, ladies of the harem, and pilgrims.

The scene of the first act is laid in Milan; the second in and near Antioch; the third and fourth near Jerusalem.

Briefly, its story or argument is this. Pagano and Arvino are the sons of one of the Lombard conquerors of Rhodes. Pagano, deeply enamoured with Viclinda, and enraged at her preference for his brother, attacked, wounded him, and then fled his country. As the curtain rises, the monks and the people are seen assembled before the Church of Ambrose, in the island of Rhodes, to celebrate the return of the pardoned culprit. He arrives, and his injured brother cordially forgives [Pg 52] and embraces him. But in the heart of the latter the same unquenchable feelings still rankle. He once more meditates the destruction of his brother and the possession of his sister-in-law. At night he invades, with an armed band, his abode; but in the dark he mistakes his victim, and kills his own father instead of his brother. Remorse takes possession of his heart, and he flies to a wilderness in Palestine to expiate his crime, and under the garb of a hermit he acquires a great reputation for sanctity. Years of repentance have elapsed; it is the moment when all Christian knights and princes have been summoned to the First Crusade, and Arvino and his followers have landed in Palestine, obedient to the call of Peter the Hermit. Here he soon hies to the holy recluse (Pagano) in his mountain retreat, seeking from the hermit counsel and consolation in his sorrows, for the Saracen chief of Antioch, in the conflict, has carried away his daughter. Pagano, concealed by his garb, promises a termination to his brother's sorrows which he knows he can effect; for Pirro, formerly his squire and confidant, now a repentant renegade, has promised to yield Antioch, where [Pg 53] he holds a command, to the Christian bands. In that city Griselda is immured; she is in the harem of Oronte, but protected by his mother, Sofia (secretly a Christian), and passionately loved by her son, who, under the double influence of love and conviction, determines to become a convert to her faith. Griselda forgets her Christian friends, and listens but too fondly to the vows of her Saracen lover; but Antioch is betrayed to the Christians, led by Arvino and Pagano; all the Saracens are put to death; and Griselda, by her lamentations over the fate of her true lover, brings down on her head the wrath of her father. In the retreat where she has taken refuge from his anger, her lover, Oronte, who has escaped from his enemies, reappears in the disguise of a Lombard. The lovers fly together, but being pursued by the Christians, Oronte receives a fatal wound; Pagano comes and takes him to his cell, and there the Saracen prince dies a Christian convert; whilst Griselda in her despair, through divine interposition, is consoled by a vision of Paradise. Pagano, who has become the guardian spirit of his injured brother, accompanies him to the siege of Jerusalem, and is wounded to death in defending [Pg 54] him. As he dies, he removes his cowl and reveals his name. His death forms the final catastrophe of the opera.

On the 11th February 1843, crowds were flocking to the Milan Theatre to hear I Lombardi—the new opera by the composer who had driven the remembrance of Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini from the heads of the Milanese. Unusual interest was aroused because the authorities, suspecting political suggestions, had sought to stop the representation of the opera. The people even brought their provisions with them, and when the moment for the performance came, a frightful odour of garlic pervaded the theatre! The patriotic subject pleased everybody, and the rendering had not proceeded far before undoubted expressions of approval issued from all parts of the house. The feverish audience detected readily exact analogies to their own political circumstances. Verdi, "saviour of his country," as some would have it, had kept up the sentiment of the Nabucco music—a sentiment which had an unmistakable revolutionary flavour and ring, soon to be mightily emphasized—and the issue was never in doubt. Soloists, chorus, and orchestra quickly had [Pg 55] their feelings echoed by the Milanese public at large.

Another triumph. Moved by the stirring music and the unstinted exertions of the principal singers, Signora Frezzolini and Signori Guasco and Derivis, the auditors were so overcome that they re-demanded number after number. The clamouring for the quintet was such that the police interfered and would not suffer it to be repeated; then the chorus, "O Signore dal tetto natio," in the fourth act brought the listeners once more to their feet; nor would they be appeased until they had heard it three times.

If only for its fortuitous association with the awakening of Lombardo-Venetia to a sense of national unity and independence, this opera must always be interesting. But I Lombardi abounds in vocal treasures, and contains some of Verdi's best early work. Take, for instance, the lovely tenor cavatina "La mia letizia infondere," and the cabaletta "Come poteva un angelo," which Oronte sings in scene 2 of the second act, and which Signor Gardoni used to render with [Pg 56] much charm and beauty of voice. Little wonder that such melodies and music predisposed the Italians towards the new young musician.

I Lombardi was certainly an advance upon Nabucco. Apart from its political associations, it contained vocal and instrumental attractions which the public were justified in expecting from the composer of Nabucco. It met with a succés d'estime only on its production in London, but this had more to do with party feeling in operatic matters at the time than with the actual merits of the work. The new and striking properties which distinguished Nabucco were still more marked in I Lombardi—so much so, indeed, that it has survived many operas and can be listened to with pleasure to-day.

In the 1846 season—Tuesday the 12th March—Mr. Lumley gave the subscribers of Her Majesty's Theatre I Lombardi, with the artists Grisi, Mario, and Fornasari, and scenery and dresses which at the time were considered unsurpassed. It was the first performance of Verdi's new opera in this country.

"Here was again a success!" writes Mr. Lumley; "nay, a great and noisy success—but [Pg 57] yet a doubtful one. After the comparative unanimity with which Nabucco had been received, it seemed necessary for the forces of the opposition to recommence the attack against a school which now threatened to make its way with the town. Party spirit on the subject was again rife. Whilst, by the anti-Verdians, I Lombardi was declared to be flimsy, trashy, worthless, the Verdi party, and the adherents of the modern Italian school, pronounced it to be full of power, vigour, and originality. The one portion asserted that it was utterly devoid of melody—the other, that it was replete with melody of the most charming kind; the one again insisted that it was the worst work of the aspirant—the other, that it was the young composer's chef d'œuvre. And in the midst of this conflict—so analogous to the old feud between the parties of Gluck and Piccini—public opinion, as usual, seemed undecided and wavering, uttering its old formula of, "Well, I don't know." The music, too, was weighed down by a rambling, ill-constructed, uninteresting libretto; and it is really difficult, under such conditions, to sunder the merit of the musical "setting" from the merit of the [Pg 58]text. I Lombardi, however, was played frequently, and to crowded houses."[11]

I Lombardi speedily travelled over Europe. As we have seen, it soon reached England, and having been adapted for the French stage, it was produced on the 26th November 1847 at the Grand Opéra of Paris under the title of Jérusalem. In its new garb, it was a failure, despite splendid singing and effective scenery. What a farcical proceeding, then, to attempt to foist this version upon the Italians under the name of Jerusalemme!

It is not surprising that Verdi was now sought after by impresarii and managers, ever on the outlook for talent and a work that may restore the too often distorted fortunes of a theatre. More than one European manager was beseeching him; but eventually the management of the Fenice theatre secured Verdi's next opera. This proved to be Ernani, produced on the 9th March 1844. Verdi chose his own subject, and entrusted Victor Hugo's drama to Piave, who subsequently became the composer's permanent librettist. The result was a tolerably good book, which Verdi set in happy vein. Its first night decided its [Pg 59]fate. Ernani was received with unstinted admiration and approval. The artists who created the parts were Signora Loewe (Elvira), who quarrelled with Verdi about her part; Signor Guasco (Ernani); and Signor Selva (Silva), the latter a singer whom the noble who owned the Fenice thought unworthy to appear on his boards, despite Verdi's recommendation, because he had been singing at a second-rate theatre!

During the nine months following the first performance of Ernani, it was produced on no less than fifteen different stages.

One or two episodes—amusing, if vexatious—attended its production. The police got wind of some exciting element in the opera, and stepped in at the last minute, objecting to several numbers, and refusing to allow a sham conspiracy to be enacted on the stage. Verdi had to give way and face the additional work and trouble; yet, after all, the Venetians got political capital out of the work, and when the spirited chorus, "Si ridesti il Leon di Castiglia," burst forth, their patriotic feelings overcame them. Another incident had to do with artistic principle. In the last act Silva had to blow upon the horn; but a susceptible aristocrat [Pg 60] could not bear the idea, and remonstrated with the composer, urging that it would desecrate the theatre!

Ernani, as we have remarked, was the work by which Verdi was first introduced to the British public; and it is, therefore, of especial interest to English readers. It involved a dispute among musical people such as has only been equalled by the famous Gluck and Piccini feud (1776) just referred to, or that great controversy engendered by Wagner's music and doctrines, the wrangle that gave us the term "music of the future," that spiteful innuendo which the enemies of the master invented to indicate the fit location of his music, and which epithet Wagner himself adopted as exactly describing an art and teachings which a debilitated and distempered age was too feeble to understand.

No one was more concerned in this musical stir than the zealous and assiduous Mr. Lumley, who had his heart and fortune in the affairs of the opera-house, Her Majesty's Theatre:—