The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari Volume 107, August 25, 1894, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari Volume 107, August 25, 1894 Author: Various Editor: Francis Burnand Release Date: July 24, 2014 [EBook #46395] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Malcolm Farmer, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

85

(A Parodic Vote of Thanks to a Town Matron, who took a House in the Country.)

My Good Mr. Punch,—I notice that in spite of all London being out of town, a number of persons have been holding, or propose holding, a meeting condemnatory of the House of Lords. I fancy, regardless of the close of the season, the site chosen has been or will be Hyde Park. Perhaps, under these circumstances, you, as the representative of the nation—equally of the aristocracy and the democracy—will allow me a few lines' space in which to express my sentiments.

My good Sir, I am considerably past middle age, and yet, man and boy, have been in the House of Peers quite half-a-dozen years. I cannot say that I was added to the number of my colleagues because I was an eminent lawyer, or a successful general, or a great statesman. I believe my claim to the distinction that was conferred upon me,—now many summers since,—was the very considerable services I was able to afford that most useful industry the paper decoration of what may be aptly termed "the wooden walls of London." When called upon to select an appropriate territorial title, I selected, without hesitation, the Barony of Savon de Soapleigh. Savon is a word of French extraction, and denotes the Norman origin of my illustrious race. Not only was I able to assist at the regeneration of the "great unwashed," but also to do considerable service to the grand cause with which my party in politics is honourably associated. I was able to contribute a very large sum to the election purse, and having fought and lost several important constituencies, was amply rewarded by the coronet that becomes me so well, the more especially when displayed upon the panels of my carriage.

You will ask me, no doubt (for this is an age of questions), what I have done since I entered the Upper Chamber? I will reply that I have secured a page in Burke, abstained from voting, except to oblige the party whips, and, before all and above all, pleased my lady wife. And yet there are those who would wish to abolish the House of Peers! There are those who would do away with our ancient nobility! Perish the thought! for in the House of Peers I see the reflection of the nation's greatness.

But you may ask me, "Would I do anything to improve that Chamber?" And I would answer, "Yes." I would say, "Do not increase its numbers; it is already large enough."

It is common knowledge that a gentleman of semi-medicinal reputation, who has been as beneficial, or nearly as beneficial, to the proprietors of hoardings as myself, wishes to be created Viscount Cough of Mixture. Yet another of the same class desires to be known to generations yet unborn as Lord Tobacco of Cigarettes; whilst a third, on account of the attention he has paid to the "understandings" (pardon the plaisanterie) of the people, is anxious to figure on the roll of honour as "Baron de Boots."

My good Mr. Punch, such an extension of the House of Peers merely for the satisfaction of the vanity of a number of vulgar and puffing men would be a scandal to our civilisation. No, my good Sir, our noble order is large enough. I am satisfied that it should not be extended, and when I am satisfied the opinions of every one else are (and here I take a simile from an industry that has given me my wealth) "merely bubbles—bubbles of soap."

And now I sign myself, not as of old, plain Joe Snooks, but Yours very faithfully,

P.S.—I am sure my long line of ancestors would agree with me. When that long line is discovered you shall hear the result.

86 87

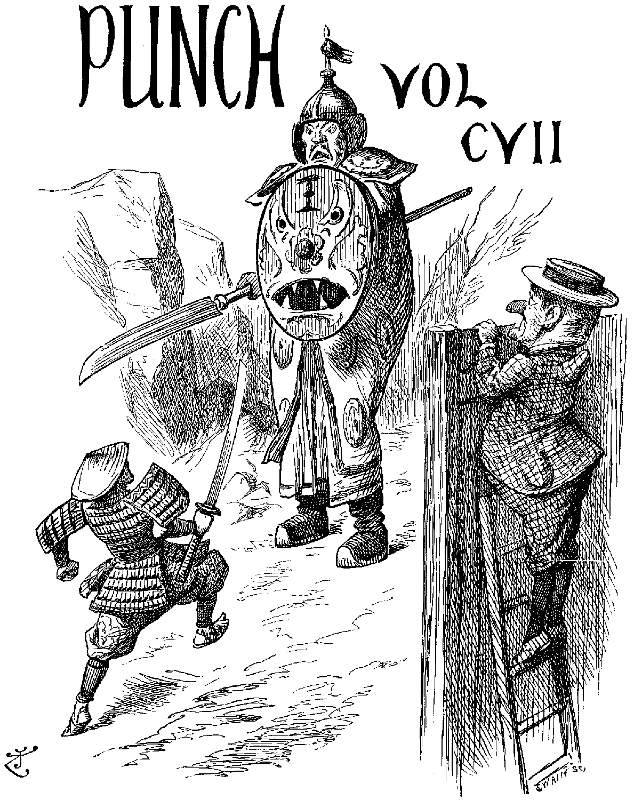

["The Bank Return shows considerable additions to the reserve and the stock of bullion."—"Times," on "Money Market."]

EMBARRAS DE RICHESSES.

The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street. "Go away! Go away with your nasty Money! I can't do with any more of it!"

ON THE SAFE SIDE.

Brown. "By George, Jones, that's a handsome Umbrella! Where did you get it?"

Jones. "I decline to answer until I've consulted my Lawyer!"

(To an Old Tune.)

The Difference between a bad German Band and a beaten Cricket Team.—One fails to play in time and the other to "play out time." 88

(A Story in Scenes.)

PART VIII.—SURPRISES—AGREEABLE AND OTHERWISE.

Scene XIII.—The Amber Boudoir. Sir Rupert has just entered.

Sir Rupert. Ha, Maisie, my dear, glad to see you. Well, Rohesia, how are you, eh? You're looking uncommonly well! No idea you were here!

Spurrell (to himself). Sir Rupert! He'll have me out of this pretty soon, I expect!

Lady Cantire (aggrieved). We have been in the house for the best part of an hour, Rupert—as you might have discovered by inquiring—but no doubt you preferred your comfort to welcoming a guest who was merely your sister!

Sir Rup. (to himself). Beginning already! (Aloud.) Very sorry—got rather wet riding—had to change everything. And I knew Albinia was here.

Lady Cant. (magnanimously). Well, we won't begin to quarrel the moment we meet; and you are forgetting your other guest. (In an undertone.) Mr. Spurrell—the Poet—wrote Andromeda. (Aloud.) Mr. Spurrell, come and let me present you to my brother.

Sir Rup. Ah, how d'ye do? (To himself, as he shakes hands.) What the deuce am I to say to this fellow? (Aloud.) Glad to see you here, Mr. Spurrell—heard all about you—Andromeda, eh? Hope you'll manage to amuse yourself while you're with us; afraid there's not much you can do now though.

Spurr. (to himself). Horse in a bad way; time they let me see it. (Aloud.) Well, we must see, Sir; I'll do all I can.

Sir Rup. You see, the shooting's done now.

Spurr. (to himself, professionally piqued). They might have waited till I'd seen the horse before they shot him! After calling me in like this! (Aloud.) Oh, I'm sorry to hear that, Sir Rupert. I wish I could have got here earlier, I'm sure.

Sir Rup. Wish we'd asked you a month ago, if you're fond of shooting. Thought you might look down on Sport, perhaps.

Spurr. (to himself). Sport? Why, he's talking of birds—not the horse! (Aloud.) Me, Sir Rupert? Not much! I'm as keen on a day's gunning as any man, though I don't often get the chance now.

Sir Rup. (to himself, pleased). Come, he don't seem strong against the Game Laws! (Aloud.) Thought you didn't look as if you sat over your desk all day! There's hunting still, of course. Don't know whether you ride?

Spurr. Rather so, Sir! Why, I was born and bred in a sporting county, and as long as my old uncle was alive, I could go down to his farm and get a run with the hounds now and again.

Sir Rup. (delighted). Capital! Well, our next meet is on Tuesday—best part of the country; nearly all grass, and nice clean post and rails. You must stay over for it. Got a mare that will carry your weight perfectly, and I think I can promise you a run—eh, what do you say?

Spurr. (to himself, in surprise). He is a chummy old cock! I'll wire old Spavin that I'm detained on biz; and I'll tell 'em to send my riding-breeches down! (Aloud.) It's uncommonly kind of you, Sir, and I think I can manage to stop on a bit.

Lady Culverin (to herself). Rupert must be out of his senses! It's bad enough to have him here till Monday! (Aloud.) We mustn't forget, Rupert, how valuable Mr. Spurrell's time is; it would be too selfish of us to detain him here a day longer than——

Lady Cant. My dear, Mr. Spurrell has already said he can manage it; so we may all enjoy his society with a clear conscience. (Lady Culverin conceals her sentiments with difficulty.) And now, Albinia, if you'll excuse me, I think I'll go to my room and rest a little, as I'm rather fatigued, and you have all these tiresome people coming to dinner to-night.

[She rises, and leaves the room; the other ladies follow her example.

Lady Culv. Rupert, I'm going up now with Rohesia. You know where we've put Mr. Spurrell, don't you? The Verney Chamber.

[She goes out.

Sir Rup. Take you up now, if you like, Mr. Spurrell—it's only just seven, though. Suppose you don't take an hour to dress, eh?

Spurr. Oh dear no, Sir, nothing like it! (To himself.) Won't take me two minutes as I am now! I'd better tell him—I can say my bag hasn't come. I don't believe it has, and, any way, it's a good excuse. (Aloud.) The—the fact is, Sir Rupert, I'm afraid that my luggage has been unfortunately left behind.

Sir Rup. No luggage, eh? Well, well, it's of no consequence. But I'll ask about it—I daresay it's all right.

[He goes out.

Captain Thicknesse (to Spurrell). Sure to have turned up, you know—man will have seen to that. Shouldn't altogether object to a glass of sherry and bitters before dinner. Don't know how you feel—suppose you've a soul above sherry and bitters, though?

Spurr. Not at this moment. But I'd soon put my soul above a sherry and bitters if I got a chance!

Capt. Thick. (after reflection). I say, you know, that's rather smart, eh? (To himself.) Aw'fly clever sort of chap, this, but not stuck up—not half a bad sort, if he is a bit of a bounder. (Aloud.) Anythin' in the evenin' paper? Don't get 'em down here.

Spurr. Nothing much. I see there's an objection to Monkey-tricks for the Grand National.

Capt. Thick. (interested). No, by Jove! Hope they won't carry it—meant to have something on him.

Spurr. I wouldn't back him myself. I know something that's safe to win, bar accidents—a dead cert, Sir! Got the tip straight from the stables. You just take my advice, and pile all you can on Jumping Joan.

Capt. Thick. (later, to himself, after a long and highly interesting conversation). Thunderin' clever chap—never knew poets were such clever chaps. Might be a "bookie," by Gad! No wonder Maisie thinks such a lot of him!

[He sighs.

Sir Rup. (returning). Now, Mr. Spurrell, if you'll come upstairs with me, I'll show you your quarters. By the way, I've made inquiries about your luggage, and I think you'll find it's all right. (As he leads the way up the staircase.) Rather awkward for you if you'd had to come down to dinner just as you are, eh?

Spurr. (to himself). Oh, lor, my beastly bag has come after all! Now they'll know I didn't bring a dress suit. What an owl I was to tell him! (Aloud, feebly.) Oh—er—very awkward indeed, Sir Rupert!

Sir Rup. (stopping at a bedroom door). Verney Chamber—here you are. Ah, my wife forgot to have your name put up on the door—better do it now, eh? (He writes it on the card in the door-plate.) There—well, hope you'll find it all comfortable—we dine at eight, you know. You've plenty of time for all you've got to do!

Spurr. (to himself). If I only knew what to do! I shall never have the cheek to come down as I am!

[He enters the Verney Chamber dejectedly.

Scene XIV.—An Upper Corridor in the East Wing.

Steward's Room Boy (to Undershell). This is your room, Sir—you'll find a fire lit and all.

Undershell (scathingly). A fire? For me! I scarcely expected such an indulgence. You are sure there's no mistake?

Boy. This is the room I was told, Sir. You'll find candles on the mantelpiece, and matches.

Und. Every luxury indeed! I am pampered—pampered!

Boy. Yes, Sir. And I was to say as supper's at ar-past nine, but Mrs. Pomfret would be 'appy to see you in the Pugs' Parlour whenever you pleased to come down and set there.

Und. The Pugs' Parlour?

Boy. What we call the 'Ousekeeper's Room, among ourselves, Sir.

Und. Mrs. Pomfret does me too much honour. And shall I have the satisfaction of seeing your intelligent countenance at the festive board, my lad?

Boy (giggling). Lor, Sir, I don't set down to meals along with the upper servants, Sir!

Und. And I—a mere man of genius—do! These distinctions must strike you as most arbitrary; but restrain any natural envy, my young friend. I assure you I am not puffed up by this promotion!

Boy. No, sir. (To himself, as he goes out.) I believe he's a bit dotty, I do. I don't understand a word he's been talking of!

Und. (alone, surveying the surroundings). A cockloft, with a painted iron bedstead, a smoky chimney, no bell, and a text over the mantelpiece! Thank Heaven, that fellow Drysdale can't see me here! But I will not sleep in this place, my pride will only just bear the strain of staying to supper—no more. And I'm hanged if I go down to the Housekeeper's Room till hunger drives me. It's not eight yet—how shall I pass the time? Ha, I see they've favoured me with pen and ink. I will invoke the Muse. Indignation should make verses, as it did for Juvenal; and he was never set down to sup with slaves!

[He writes.

Scene XV.—The Verney Chamber.

Spurr. (to himself). My word, what a room! Carpet all over the 89 walls, big fourposter, carved ceiling, great fireplace with blazing logs,—if this is how they do a vet here, what price the other fellows' rooms? And to think I shall have to do without dinner, just when I was getting on with 'em all so swimmingly! I must. I can't, for the credit of the profession—to say nothing of the firm—turn up in a monkey jacket and tweed bags, and that's all I've got except a nightgown!... It's all very well for Lady Maisie to say "Take everything as it comes," but if she was in my fix!... And it isn't as if I hadn't got dress things either. If only I'd brought 'em down, I'd have marched in to dinner as cool as a——(he lights a pair of candles.) Hullo! What's that on the bed? (He approaches it.) Shirt! white tie! socks! coat, waistcoat, trousers—they are dress clothes!... And here's a pair of brushes on the table! I'll swear they're not mine—there's a monogram on them—"U.G." What does it all mean? Why, of course! regular old trump, Sir Rupert, and naturally he wants me to do him credit. He saw how it was, and he's gone and rigged me out! In a house like this, they're ready for emergencies—keep all sizes in stock, I daresay.... It isn't "U. G." on the brushes—it's "G. U."—"Guest's Use." Well, this is what I call doing the thing in style! Cinderella's nothing to it! Only hope they're a decent fit. (Later, as he dresses.) Come, the shirt's all right; trousers a trifle short—but they'll let down; waistcoat—whew, must undo the buckle—hang it, it is undone! I feel like a hooped barrel in it! Now the coat—easy does it. Well, it's on; but I shall have to be peeled like a walnut to get it off again.... Shoes? ah, here they are—pair of pumps. Phew—must have come from the Torture Exhibition in Leicester Square; glass slippers nothing to 'em! But they'll have to do at a pinch; and they do pinch like blazes! Ha, ha, that's good! I must tell that to the Captain. (He looks at himself in a mirror.) Well, I can't say they're up to mine for cut and general style; but they're passable. And now I'll go down to the Drawing Room and get on terms with all the smarties!

[He saunters out with restored complacency.

The first annual meeting of this society, which, as our readers will remember, has been in process of formation for some years past, was held yesterday. We cannot congratulate the society on its decision to exclude reporters. It is true that our representative, on seeking admission, was informed that his presence would be unnecessary, as members of the society, having for some time past done their own reviewing, intended for the future to report themselves. The public, however, whose eager interest in literature is sufficiently attested not only by the literary page of democratic newspapers, but by the columns which even reactionary journals devote to higher criticism and literary snippets—the public, we say, will not brook this absurd plea, and will refuse to accept any but an impartial report of a gathering such as was held yesterday. This we have obtained, and we now proceed to publish it for the benefit of the world.

The meeting opened with a prayer of two thousand words specially written for the occasion by Mr. Richard L- G-lli-nne in collaboration with Mr. Robert B-ch-n-n. As this is shortly to be published in the form of a joint letter to the Daily Chronicle it is only necessary to say at present that it combines vigour of expression with delicacy of sentiment and grace of style in the very highest degree. By the way, we may mention that the new Prayer-book of the Society is to be published by Messrs. E-k-n m-tth-ws and J-hn L-ne, at the "Bodley Head," before the end of the year. It will be profusely illustrated by MESSRS. A-br-y B-ard-l-y and W-lt-r S-ck-rt, who have also designed for it a special fancy cover. Only three hundred copies will be issued. To return, however, to the meeting.

After harmony had been restored, Mr. W-lt-r B-s-nt asked leave to say a few words. His remarks, in which he was understood to advocate the compulsory expropriation of publishers, were at first listened to with favour. Happening incautiously to say a word or two in praise of a Mr. Dickens and a Mr. Thackeray he was groaned down after a sturdy struggle. Mr. Dickens and Mr. Thackeray were not, we understand, present in the room at the time.

Mr. H-b-rt Cr-ck-nth-rpe rose and denounced the previous speaker. Literature, he declared, must be vague. What was the use of knowing what you were driving at? What was the use of anyone knowing anything? Personally he didn't mean to know more than he could help, and he could assure the meeting that he could help a great deal; yes, he could help his fellow-creatures to a right understanding of the value of patchwork and jerks. That was the religion of humanity.

Mr. N-rm-n G-le said he wasn't much good speaking, but he could do something in the dairy and orchard style. He then gave the following example:—

A loud cheer greeted the recital of this charming pastoral, and one editor, who is not often a victim to mere sentiment, said it reminded him of his happy childhood, when he used to take Dr. Gregory's powders after a day spent in the neighbouring farmer's orchard.

The next speaker was G-orge Eg-rt-n. All women, she said, must be Georges. George Sand and George Eliot were women she believed. George Meredith was an exception, but that only proved her rule. Women were a miserable lot: it was their own fault. Why marry? ("Hear, hear," from Mrs. Mona Caird.) Why be born at all? She paused for a reply.

At this point Mr. W. T. St-ad entered the room and offered to talk about "Julia in Chicago," but the meeting broke up in confusion, without the customary vote of thanks to the Chair.

(A Serene Ducal Romance of the Future.)

His Highness was smoking a pipe at the close of the day in the fair realm of Utopia. He had finished dinner, and was discussing his lager beer, which had quite taken the place of coffee.

"Dear me," said the Duke, rather anxiously, as he noticed the Premier was seating himself in a chair in his near neighbourhood; "I am afraid I am in disgrace."

"Not at all, Sir," replied the Minister, graciously. "On the contrary, in the name of the people of Utopia, I beg to offer you my sincere thanks."

"For what?" queried the Duke.

"For doing your duty, my liege. Not that that is a novelty, for, as a matter of fact, you are always doing it."

"I am pleased to hear you say so," observed His Highness; "as I was under the impression that I had rather shirked my engagements."

"Not at all, Sir—not at all. If you consult your memory, you will find you carried out to-day's programme to the letter."

"Had I not to lay a foundation stone, or something, this morning?"

"Assuredly; and you touched a cord as you were getting up, and immediately the machinery was set in motion, and the stone was duly laid. Much better than driving miles to have to stand in a drafty marquee."

"And had I not to open an exhibition?"

"Why, yes. And you opened it in due course. Your equerry represented you and ground out your speech from the portable phonograph."

"Well, really, that was very ingenious," remarked His Highness. "But was I not missed?"

"You would have been, Sir," returned the Premier, "had we not had the forethought to send down the lantern that gives you in a thousand different attitudes. By revolving the disc rapidly the most life-like presentment was offered immediately."

"Excellent! and did I do anything else?"

"Why your Highness has been hard at work all day attending reviews, opening canals, and even presiding at public dinners. Thanks to science we can reproduce your person, your speech, your very presence at a moment's notice."

"Exceedingly clever!" exclaimed His Highness. "Ah, how much better is the twentieth century than its predecessor!"

And no doubt the sentiment of His Highness will be approved by posterity. 90

HOLIDAY CHARACTER SKETCHES.

Little Binks loves Clara Purkiss, who loves Big Stanley Jones, who loves himself and nobody else in the World!

Which is the most to be pitied of the three?

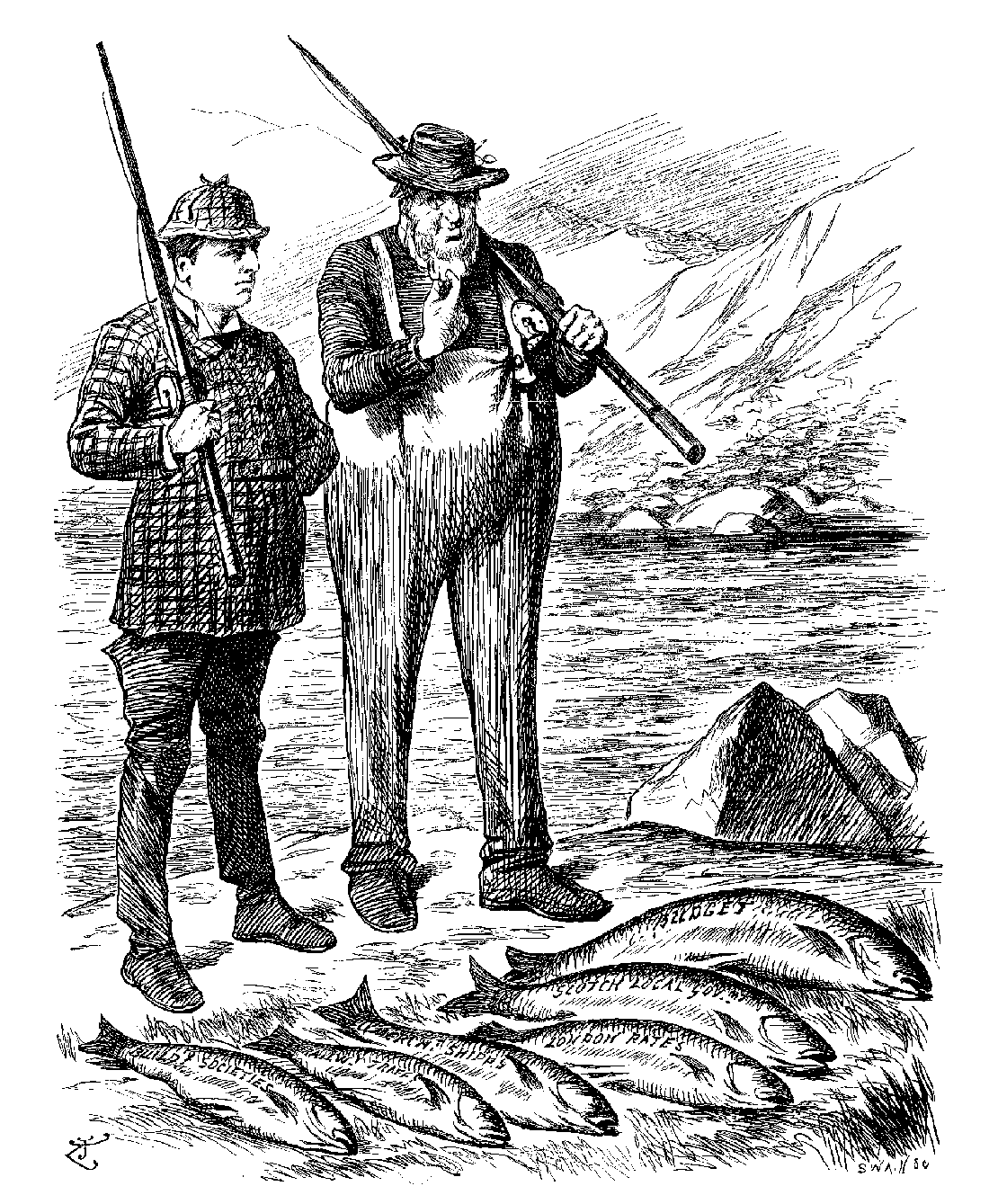

A Waltonian Fragment.

First Piscator, R-s-b-ry. Second Piscator, H-rc-rt.

First Piscator. Oh me, look you, master, a fish, a fish!

[Loses it.

Second Piscator. Aye, marry, Sir, that was a good fish; if I had had the luck to handle that rod, 'tis twenty to one he should not have broken my line as you suffered him; I would have held him, as you will learn to do hereafter; for I tell you, scholer, fishing is an art, or at least it is an art to catch fish. Verily that is the second brave Salmon you have lost in that pool!

First Piscator. Oh me, he has broke all; there's half a line and a good flie lost. I have no fortune, and that Peers' Pool is fatal fishing.

Second Piscator. Marry, brother, so it seemes—to you at least! Wel, wel, 'tis as small use crying over lost fish as spilt milk; the sunne hath sunk, the daye draweth anigh its ende; let us up tackle, and away!

First Piscator. Look also how it begins to rain, and by the clouds (if I mistake not) we shal presently have a smoaking showre. Truly it has been a long, rough day, and but poorish sport.

Second Piscator. Humph! I am fairly content with my catch, and had all been landed that have been hookt—but no matter! "Fishers must not rangle," as the Angler's song hath it.

First Piscator. Marry, no indeed! (Sings.)

Second Piscator. Well sung, brother! Oh me, but even at our peaceful and vertuous pastime, there bee certain contentious and obstructive spoil-sports now. These abide not good old Anglers' Law, but bob and splash in other people's swims, fray away the fish they cannot catch, and desire not that experter anglers should, do muddy the stream and block its course, do net and poach and foul-hook in such noisy, conscienceless, unmannerly sort, that even honest angling becometh a bitter labour and aggravation.

First Piscator. Marry, yes brother! the Contemplative Man's Recreation is verily not what it once was. What would the sweet singer, Mr. William Basse, say to the busy B's of our day; Dubartas to B-rtl-y, or Mr. Thomas Barker, of pleasant report, to Tommy B-wl-s?

Second Piscator. Or worthy old Cotton to the cocky Macullum More?

First Piscator. Or the equally cocky Brummagem Boy?

Second Piscator. Or Dame Juliana Berners to B-lf-ur?

First Piscator. Or Sir Humphrey Davy to the haughty autocrat of H-tf-ld?

Second Piscator. Wel, wel, I hate contention and obstruction and all unsportsmanlike devices—when I am fishing.

First Piscator. And so say I. (Sings.)

Second Piscator. The Commons full of opulence,

First Piscator. Marry, brother, and would that I could always do so. But doomed as we often are to angle in different swims, I may not always land the big fish that you hook, or even——

Second Piscator. Wel, honest scholer, say no more about it, but let us count and weigh our day's catch. By Jove, but that bigge one I landed after soe long a fight, and which you were so luckie as to gaff in that verie snaggy and swirly pool itselfe, maketh a right brave show on the grassie bank! And harkye, scholer, 'tis a far finer and rarer fish than manie woule suppose at first sight!

[Chuckleth inwardly.

First Piscator. You say true, master. And indeed the other fish, though of lesser bigness, bee by no manner of meanes to be sneezed at. Marry, Master, 'tis none so poor a day's sport after all—considering the weather and the much obstruction, eh?

Second Piscator. May bee not, may bee not! Stil, I could fain wish, honest scholer, you had safely landed those two bigge ones you lost in Peers' Pool, out of which awkward bit of water, indeed, I could fain desire we might keep all our fish! 91

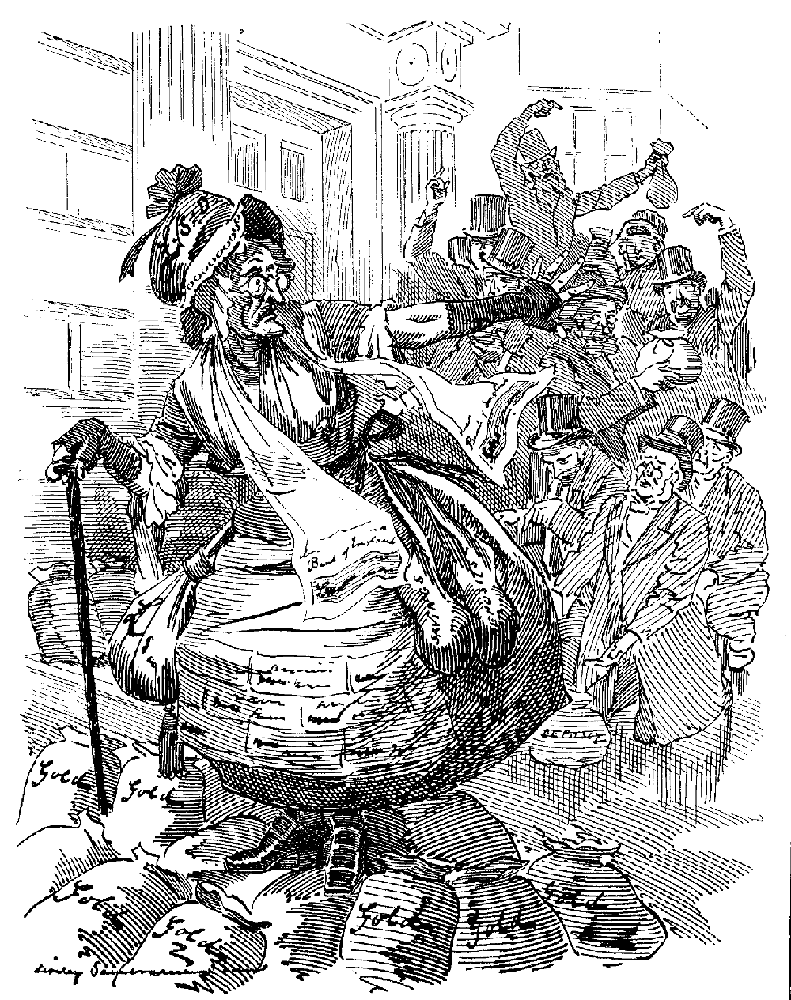

COUNTING THE CATCH.

Rosebery. "NOT SUCH A BAD DAY AFTER ALL!"

Harcourt. "NO! WISH YOU'D LANDED THOSE OTHERS ALL THE SAME!!"

92 93

A Pessimistic Tale.

94

PEARLS BEFORE SWINE.

The Vicar. "What do you think of that Burgundy? It's the last Bottle of some the dear Bishop gave me. It cost him Eighteen Shillings a Bottle!"

The Major. "Very nice! But I should just like you to try some I gave Twelve Shillings a Dozen for!"

How werry particklar sum peeple is in having it adwertised where they have gone to spend their summer holliday. I wunce saw it stated, sum years ago, that the Markis of Sorlsberry had gone with the Marchoness to Deep, I think it was, and then follered the staggering annowncement that Mr. Deputy Muggins and Mrs. Muggins was a spending a hole week at Gravesend! I'm a having mine at Grinnidge, and had the honner last week of waiting upon the Ministerial Gents from Westminster, and a werry jowial lot of Gents they suttenly seems to be.

I likes Grinnidge somehow; it brings back to fond memmory the appy days when I fust preposed to my Misses Robert in Grinnidge Park, and won from her blushing lips a fond awowal of her loving detachment for me!

Ah! them was appy days, them was, and never cums more than wunce to us; no, not ewen in Grinnidge Park.

I'm told as how as Appy Amsted is not at all a bad place for this sort of thing; but I cannot speak from werry much pussonal xperience there myself.

Having a nour or two to spare before the Westminster Dinner, I took a strol in the butiful Park. Not quite the place for adwenters, but I had a little one there on that werry particklar day as I shant soon forget.

I was a setting down werry cumferal on a nice cumferal seat, when a nice looking Lady came up to me, and setting herself down beside me asked me wery quietly if I coud lend her such a thing as harf a crown! I was that estonished that I ardly knew what to say, when to my great surprise she bust out a crying, and told me as how as she had bin robbed, and had not a penny to take her home to London! What on airth coud I do? I coudn't say as I hadn't no harf crown coz I had one, and I carnt werry well tell a hunblushing lie coz I allers blushes if I tries one, so I said as how as it was the only one as I had, and so I hoped as she woud return it to me to-morrow, and I told her my adress, when she suddenly threw her arms round my neck and acshally kist me, and then got up and ran away! and I have lived ever since in a dredful state of dowt and unsertenty for fear as she shoud call when I was out and tell Mrs. Robert the hole particklers! and ewen expect her to believe it!

(Fragment from a Romance of the Future.)

The successful General, after winning the great victory, acted with decision. He cut all the telegraph wires with his own hands, until there was but one left in the camp—that which had its outlet in his own tent. He called for the special correspondents. They came reluctantly, writing in their note-books as they approached him.

"Gentlemen," said he, with polite severity, "I have no wish to deal harshly with the Press. I am fully aware of the services it does to the country. But, gentlemen, I have a duty to perform. I cannot allow you to communicate to your respective editors the glorious result of this day's fighting. For a couple of hours you must be satisfied to restrain your impatience."

"It will yet be in time for the five o'clock edition," murmured one of the scribes.

"And I shall be able to get it into the Special," murmured another.

Then the General bowed and retired to his own tent. At last he was alone. Over the receiver to the telephone was a board inscribed with various numbers, with names attached thereto. He saw that 114 stood for "Wife," 12,017 for "Mother-in-law," and 10 for "Junior United Service Club." But he selected none of these.

"No. 7," he cried, suddenly applying his lips to the receiver and ringing up, "are you there?"

"Why, certainly; what shall I do?"

"Why, buy 30,000 Consols for me," was the prompt reply. And then the General a few minutes later added, "Have you done it?"

"I have—for the next account."

And then the warrior smiled and released the Press-men. Nay, more, he ordered the telegraph wires to be repaired. All was joy and satisfaction. The glorious news was flashed in a thousand different directions. The name of the general received immediate immortality.

And the great commander was more than satisfied. His fortune was assured. Before allowing the news to be spread abroad he had taken the precaution to do a preliminary deal with his stockbroker! 95

"FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD."

Tourist from London (to young local Minister). "How quiet and peaceful it seems here!"

Minister. "Eh, Friend, it seems peacefu'. Wha wad think we were within Seven Miles o' Peebles!"

[At Baku, on the Caspian, a Society has been formed to abolish hand-shaking and kissing, on the ground that bacilli are propagated by such personal contact. The ladies, however, have protested against this to the Governor-General.

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TORY, M.P.

House of Lords. Monday, August 13.—Sorry I didn't hear the Duke of Argyll. Have been told he is one of finest orators in House; a type of the antique; something to be cherished and honoured.

"Were you ever," Sark asked, "at Oban when the games were going on? Very well then, you would see the contest among the pipers. You have watched them strutting up and down with head thrown back, toes turned out, cheeks extended, and high notes thrilling through the shrinking air. There you have Duke of Argyll—God bless him!—addressing House of Lords. He is not one piper, but many. As he proceeds, intoxicated with sound of his own voice, ecstatic in clearness of his own vision, he competes with himself as the pipers struggle with each other until at last he has, in a Parliamentary sense of course, swollen to such a size that there is no room in the stately chamber for other Peers. Nothing and nobody left but His Grace the Duke of Argyll. Towards end of sixty minutes spectacle begins to pall on wearied senses; but to begin with, it is almost sublime. For thirty-two years, he told Rosebery just now, he had sat on the opposite benches, a Member of the Liberal Party. He sat elsewhere now, but why? Because he was the Liberal Party; all the rest like sheep had gone astray. Pretty to see the Markiss with blushing head downcast when Argyll turned round to him and, with patronising tone and manner, hailed him and his friends as the only party with whom a true Liberal might collogue. In some circumstances, this bearing would be insupportably bumptious. In the Duke, with the time limit hinted at, it is delightful. He really unfeignedly believes it all. Sometimes in the dead unhappy night, when the rain is on the roof (not an uncommon thing in Inverary) he thinks in sorrow rather than in anger of multitudes of men hopelessly in the wrong; that is to say, who differ from his view on particular subjects at given times."

Business done.—Second Reading of Evicted Tenants Bill moved in Lords.

Tuesday.—For awhile last night, whilst Lansdowne speaking, Clanricarde sat on rear Cross Bench immediately in front of Bar where mere Commoners are permitted to stand. Amongst them at this moment were Tim Healy, O'Brien, and Sexton, leaning over rail to catch Lansdowne's remarks. Before them, almost within hand reach, certainly approachable at arm's length with a good shillalegh, was the bald pate of the man who, from some points of view, is The Irish Question. Clanricarde sat long unconscious of the proximity. Sark, not usually a squeamish person, after breathlessly watching this strange suggestive contiguity, moved hastily away. This is a land of law and order. Differences, if they exist, are settled by judicial processes. But human nature, especially Celtic nature, is weak. The bald pate rested so conveniently on the edge of the bench. It was so near; it had schemed so much for the undoing of hapless friends in Ireland. What if * * *

To-night Clanricarde instinctively moved away from this locality. Discovered on back bench below gangway, from which safe quarter he delivered speech, showing how blessed is the lot of the light-hearted peasant on what he called "my campaign estates."

The Markiss and Clanricarde rose together. It was ten o'clock, the hour appointed for Leader of Opposition to interpose; in anticipation of that event the House crowded from floor to side galleries garlanded with fair ladies. Privy Councillors jostled each other on steps of Throne; at the Bar stood the Commons closely packed; Tim Healy, anxious not again to be led into temptation, deserted this quarter; surveyed scene from end of Gallery over the Bar. The Markiss stood for a moment at the table manifestly surprised that any should question his right to speak. According to Plan of Campaign prepared beforehand by Whips now was his time; Rosebery to follow; and Division taken so as to clear House before midnight. Clanricarde recks little of Plans of Campaign: stood his ground and finally evicted the Markiss; cast him out by the roadside with no other compensation than the sympathy of Halsbury and of Rutland, who sat on either side of him.

When opportunity came the Markiss rose to it. Speech delightful 96 to hear; every sentence a lesson in style. Hard task for young Premier to follow so old and so perfect a Parliamentary hand. Markiss spoke to enthusiastically friendly audience. Rosebery recognised in himself the representative of miserable minority of thirty; undaunted, undismayed, he played lightly with the ponderous personalities of Argyll, and looking beyond the heads of the crowd of icily indifferent Peers before him, seemed to see the multitude in the street, and to hear the murmur of angry voices.

Business done.—Lords throw out Evicted Tenants Bill by 249 votes against 30.

Thursday, Midnight.—Spent restful evening with Indian Budget. There is nothing exceeds indignation with which Members resent postponement of opportunity to consider Indian Budget, except the unanimity with which they stop away when it is presented. Number present during Fowler's masterly exposition not equal to one per ten million of the population concerned. Later, Chaplin endeavoured to raise drooping spirits by few remarks on bi-metallism. Success only partial. Clark did much better. Genially began evening by accusing Squire of Malwood of humbugging House. That worth at least a dozen votes to Government in Division that followed. Tim Healy, who can't abear strong language, was one who meant to vote against proposal to take remaining time of Session for Ministers. After Clark's speech, voted with and for the Squire.

Clark closed pleasant evening by insisting on Division upon Statute Law Revision Bill running through Committee.

"Will the hon. Member name a teller," said Chairman, blandly.

"Mr. Conybeare," responded Clark, instinctively thinking of Member for Camborne as most likely to help in the job he had in hand.

But Conybeare is a reformed character. Even at his worst must draw line somewhere. Drew it sharply at Clark. Appeared as if game was up. On the contrary it was Weir. Deliberately fixing a pair of cantankerous pince-nez that seem to be in chronic condition of strike, Weir gazed round angered Committee. With slowest enunciation in profoundest chest notes he said, "I will tell with the hon. Member."

Committee roared with anguished despair; but, since procedure in case of frivolous and vexatious Division seems forgotten by Chair, no help for it. If there are two Members to "tell," House must be "told." But there tyranny of two ceases. You may take horse to water but cannot make him drink. Similarly you may divide House, but cannot compel Members to vote with you. Thus it came to pass that after Division Clark and Weir marched up to table with confession that they had not taken a single man into the Lobby with them. They had told, but they had nothing to tell.

"They're worse off by a moiety than the Squire in the Canterbury Tales," said Sark—

"Yes, poor needy Knife-grinders," said the other Squire; "if they'd only thought of it when asked by the Clerk, 'How many?' they might have answered, Members, God bless you, we have none to tell.'"

Business done.—Indian Budget through Committee.

Friday.—Something notable in question addressed by Bryn Roberts to Home Secretary. Wants to know "whether he is aware that the Mr. Williams, the recently appointed assistant inspector, who is said to have worked at an open quarry, never worked at the rock but simply, when a young man, used to pick up slabs cast aside by the regular quarrymen, and split them into slates; and that, ever since, he has been engaged as a pupil teacher and a schoolmaster."

Shall put notice on paper to ask Bryn Roberts whether the sequence therein set forth is usual in Wales, and whether picking up slabs and splitting them into slates is the customary pathway to pupil teachership.

Long night in Committee of Supply; fair progress in spite of Weir and Clark. Tim Healy sprang ambush on House of Lords: moved to stop supplies for meeting their household expenses. Nearly carried proposal, too. Vote sanctioned by majority of nine, and these drawn from Opposition.

Business done.—Supply.

Or, The Grand Old Georgic.

["The whole care of poultry, the production of eggs, care of bees, and the manufacture of butter—of itself a most important branch of commerce—are really included within the purposes of this little institution."—Mr. Gladstone on "Small Culture," at the Hawarden Agricultural and Horticultural FÍte, August 14, 1894.]

(On his Revival of the Ministerial Whitebait Dinner at the "Ship," Greenwich, Wednesday, August 15, 1894.)

(On the Eve of Prorogation.)

Would-be Abdiel (M.P.) loquitur:—

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation are as in the original.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari Volume

107, August 25, 1894, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 46395-h.htm or 46395-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/6/3/9/46395/

Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Malcolm Farmer,

Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.