THE DARDANELLES

COLOUR SKETCHES FROM GALLIPOLI

WRITTEN AND DRAWN BY

NORMAN WILKINSON, R.I.

With Thirty Full-Page Plates in Colour, reproduced from Water-Colour Drawings made on the spot, and a number of Black-and-White Illustrations

SECOND IMPRESSION

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

FOURTH AVENUE & 30TH STREET, NEW YORK

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS

1916

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | FIRST IMPRESSIONS | 1 |

| II | THE LANDING AT SUVLA BAY, AUGUST 6-7 | 9 |

| III | OFF THE LEFT FLANK AT HELLES | 23 |

| IV | TRAWLERS IN THE DARDANELLES | 34 |

| V | BEACH-PARTIES | 42 |

| VI | SUBMARINES | 50 |

| VII | WOUNDED | 56 |

| HELLES | Facing page | ||

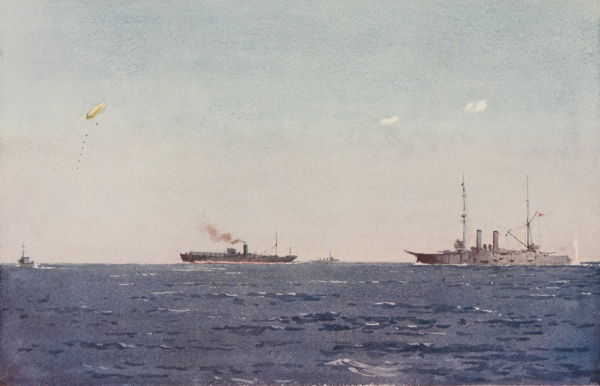

| *1. | H.M.S. THESEUS | Frontispiece | |

| This cruiser, 25 years old, which has now special arrangements for withstanding submarine attacks, is supporting the Army off the left flank. She is firing at Turkish gun emplacements, an aeroplane being used to spot the fall of shot. | |||

| *2. | SHELLS FALLING ON THE BASE CAMP AT HELLES | 62 | |

| *3. | OFF THE LEFT FLANK AT HELLES | } | 64 |

| *4. | MONITORS SHELLING YENI SHER VILLAGE AND ASIATIC BATTERIES | } | |

| *5. | FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN SHELLING ACHI BABA | 66 | |

| *6. | FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN'S 12-IN. SHELLS BURSTING ON WESTERN SLOPES OF ACHI BABA | 68 | |

| *7. | BALLOON-SHIP HECTOR WITH KITE BALLOON UP, "SPOTTING," OFF THE LEFT FLANK | 70 | |

| SUVLA BAY | |||

| *8. | LANDING AT "A" BEACH, AUGUST 7, 5.30 A.M. | 72 | |

| *9. | TROOPS LANDING AT "C" BEACH, AUGUST 7 | 74 | |

| *10. | "C" BEACH, AUGUST 8 | 76 | |

| *11. | DRESSING STATION—"A" BEACH | } | 78 |

| *12. | SHIP'S BOATS GOING OFF TO A HOSPITAL SHIP WITH WOUNDED | } | |

| *13. | H.M.S. TALBOT IN SUVLA BAY SHELLING ENEMY RIDGES AT DUSK | 80 | |

| *14. | SALT LAKE AND CHOCOLATE HILL | 82 | |

| *15. | LALLA BABA | } | 84 |

| *16. | LOOKING TOWARDS THE VILLAGE OF ANAFARTA | } | |

| *17. | H.M.S. SARNIA LANDING TROOPS IN SUVLA BAY | 86 | |

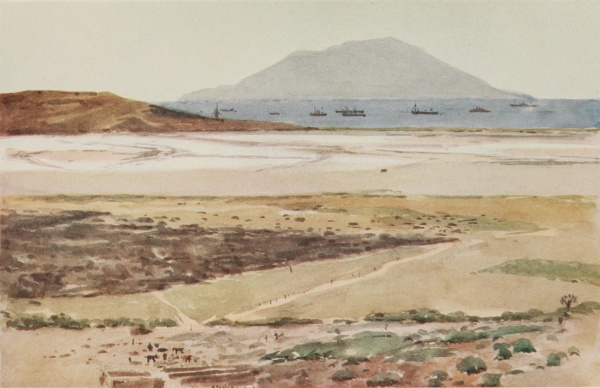

| *18. | SALT LAKE FROM CHOCOLATE HILL | 88[viii] | |

| *19. | TRANSPORTS UNDER SHELL-FIRE—SUVLA BAY | 90 | |

| *20. | DRESSING STATION—"A" BEACH | 92 | |

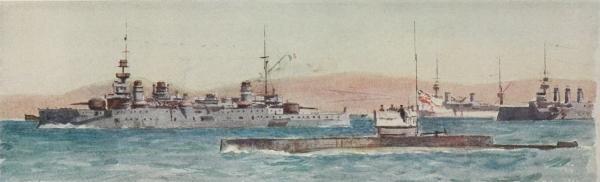

| *21. | SUPPORTING SHIPS AT THE SUVLA LANDING | } | 94 |

| *22. | ANZAC | } | |

| *23. | ANZAC | 96 | |

| *24. | MOTOR LIGHTERS | } | 98 |

| 25. | GENERAL SIR IAN HAMILTON'S HEADQUARTERS | } | |

| 26. | SEAPLANE BASE | 100 | |

| 27. | SEAPLANES AT KEPHALO | 102 | |

| 28. | H.M.S. EXMOUTH IN KEPHALO HARBOUR | 104 | |

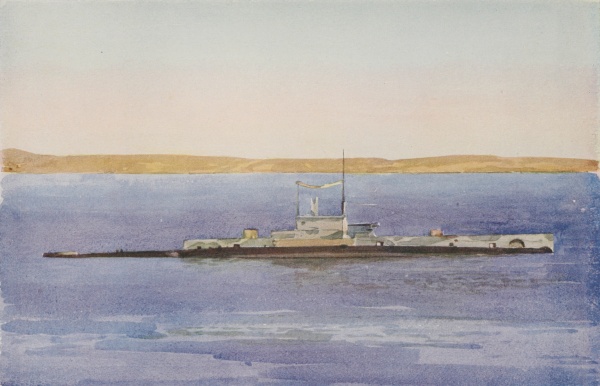

| 29. | SUBMARINE E11 AT KEPHALO | 106 | |

| 30. | H.M.S. BEN-MY-CHREE AT KEPHALO | 108 | |

| 31. | HOSPITAL SHIPS AT KEPHALO | 110 | |

| 32. | FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN | 112 | |

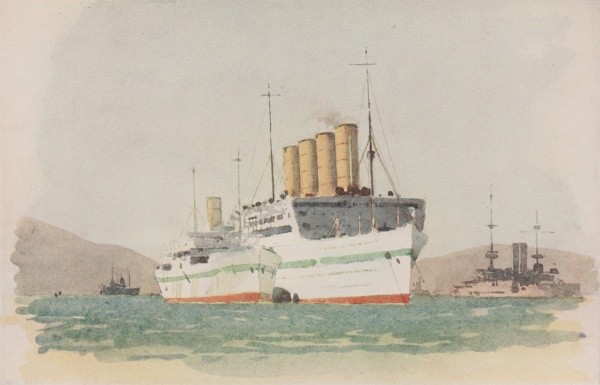

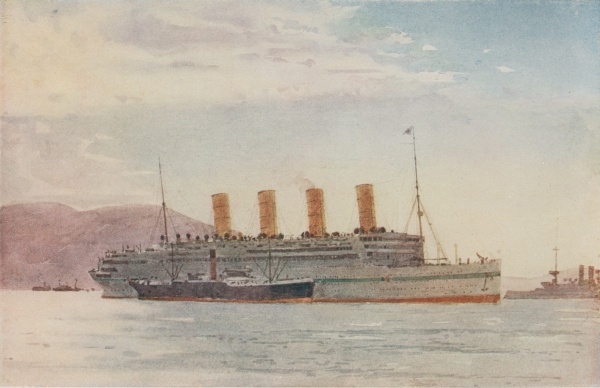

| 33. | HOSPITAL SHIP AQUITANIA | 114 | |

| 34. | SUBMARINE E2 RETURNING FROM THE SEA OF MARMORA | } | 116 |

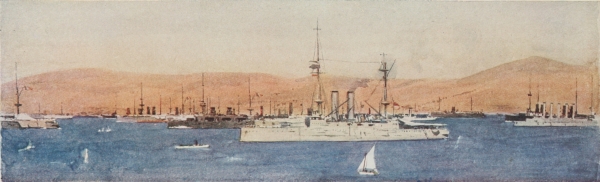

| 35. | MUDROS HARBOUR | } | |

| 36. | HOSPITAL SHIP AQUITANIA AT MUDROS | 118 | |

THE DARDANELLES

Before entering upon the subject of this chapter I cannot help a passing allusion to the lack of pictorial records of this war—records made by artists of experience, who actually witness the scenes they portray.

Our descendants will surely regret the omission when they try to gather an impression of the greatest war in history from the inadequate material obtainable.

I do not lose sight of the fact that many professional artists are fighting with our army in France and elsewhere. But life in the trenches is so arduous that it is doubtful if many records will come to us from this source.

The start of my journey was not at all what I had intended. I had imagined myself busily sketching [2]our departure and attempting to get some of the delightful colour and abundant movement of the lower Thames.

In actual fact, I spent most of this time lying on a settee, trying to overcome the effects of inoculation, though rather cheered, it is true, by the thought of the annoyance set up amongst the millions of germs inhabiting my system.

I made several efforts to go on deck, but was forced each time to give in and return to my cabin.

This was the more annoying, as we were passing through what to any traveller by sea, and to me especially, was the most interesting zone: full of romance and mystery, with stories of sunken submarines, rumours of nets and mines, and all the strange happenings of this strangest of wars.

There was naturally a certain amount of speculation on the steamer as to the possibility of attack by submarine: this new factor in modern warfare, which, from a romantic point of view, has so largely conduced to the elimination of spectacular fighting.

At the time of sailing we had heard of submarine activity in the western entrance to the Channel, though the apparent indifference of the passengers was a wonderful testimony to the calmness [3]of the Briton in the presence of a very real danger. However, hopes ran fairly high that we might soon get into safe waters, as we were favoured with a fairly heavy summer gale, which should, with luck, see us well round Ushant and down the bay.

We were pushing along doing a steady ten knots with our fore-deck frequently taking it green; but, well loaded as we were with general cargo, the ship was wonderfully easy in motion. This was in comforting contrast to a tramp-steamer close by, which looked as if she wanted to see how far she could roll without turning over.

Ships bound for the Mediterranean and to other parts are more scattered nowadays than formerly. Since the war they have avoided the recognised trade routes. Probably there may be enemy submarines bound out to the Eastern Mediterranean, but the likelihood of attack from these appeared to us small. After all, they would surely reserve their stock of torpedoes for a more important quarry, and, in any case, would hardly be likely to advertise their presence before arriving in their intended zone of operations.

During the night we passed a number of patrol boats keeping their ceaseless vigil. The patrol [4]service will, when the war is over, undoubtedly reap the full meed of praise to which they are entitled. It is utterly impossible for the landsman to grasp the soul-wearying work on patrol vessels. Frequently of quite small tonnage, keeping the seas in every kind of weather, not bound anywhere in particular, but just slogging to and fro on a set beat, rarely thought of except by the relatives and friends of those serving in them.

We reached Gibraltar in two or three days, during which time no alarms from submarines disturbed our peace. The sight of the Rock for the first time must frequently call forth an exclamation on the strangeness of events which have enabled us to take and hold so fine a strategical position. Isolated as it is from any other of our possessions, it has certainly served us well in the Dardanelles campaign.

Malta was made in the early morning, and it certainly looked a gem set in a sea of opal, although closer acquaintance found it stiflingly hot. Our time here was short, as we were ordered to a vessel leaving early next morning for Mudros, the base in the island of Lemnos. The ship in which we took passage was one of an entirely new class, specially designed for the destruction of submarines. On our passage up, a matter of three days, a sharp lookout [5]was kept, as we were now nearing the danger zone. For some reason difficult to discover there appeared to be a lull in the operations of these craft, due, probably, to the numerous devices employed to restrict their activities. Nevertheless, continual reports were coming in of their being sighted, and our Captain was anxious to try the efficacy of his means of offence, but we were disappointed or otherwise, according to our various temperaments, for we sighted nothing suspicious.

On the third day a French destroyer, with whom we exchanged recognition signals, steamed up to us for a closer inspection. This denoted our close proximity to the great naval base from which the operations in this theatre of war were largely conducted.

A distant view of Mudros, one of the finest natural harbours in the eastern Mediterranean, showed a vast concourse of ships, which grew in interest and numbers as we approached. Eventually we steamed between lines of warships to an anchorage given us by signal. I have seen many reviews and naval pageants, but nothing to compare, in interest, with the assemblage of ships that we now witnessed. British battleships, French battleships, cruisers of both nations; a Russian cruiser, the Askold (which had incidentally been badly [6]hammered in the war with Japan); destroyers, torpedo boats of all ages, submarines (some fresh with the laurels of raids in the Sea of Marmora), North Sea trawlers, tramp-steamers, transports, food-ships, motor-boats, Greek sailing vessels, motor-barges for landing troops, private yachts taken over by the Admiralty (the Admiral conducting operations being himself in one of these), and endless other craft gathered from everywhere to assist in the enormous undertaking of supplying food and munitions and to guard the routes to the various other bases established in the islands around. Towering above all the vessels could be seen the Aquitania and the Mauretania, their immense bulk dwarfing every ship in the harbour.

Ashore were camps in every direction, that of the French being the most conspicuous, as, owing to its longer occupation, the ground had lost every trace of vegetation and had become a vast arid mound, looking terribly hot, with clouds of sand blowing continually across it.

The fact of so many battleships and cruisers being in the harbour was an eloquent tribute to the moral influence of submarines. These craft would appear to have been less active recently, whether as a result of means taken to combat them (the sea is a maze of [7]nets), or whether from engine troubles or shortage of petrol, it is impossible to say. On the other hand, they may hope to lull us into a sense of false security, and thus to entice the larger ships out. Whatever the cause, our belief in their inactivity is strengthened by the fact that a number of warships are patrolling the seas continually without interference.

We spent a few days in this port before an opportunity occurred to get nearer to the area of hostilities. I was fortunate enough to be appointed to a ship which left almost immediately for Kephalo, our base in the island of Imbros, some ten miles distant from the enemy coast. After a rapid passage through a sea studded with indicator nets, we arrived at Kephalo. A fair enough anchorage, this, in summer, though a practically continuous breeze from the north-east, sometimes of considerable strength, is apt to make it uncomfortable for small craft.

The setting here is rather more picturesque than Mudros, by reason of the smaller water area and higher hills on the northern side. Here again a large concourse of ships was gathered, mostly transports, though two vessels, the balloon-spotting ship Hector and the plane-carrying and repair ship Ark Royal, were of unusual interest. The flagship Exmouth, with a large collier made fast on either [8]beam, was evidently determined not to allow the marauding submarine any opportunity of repeating her Majestic and Triumph successes.

Nothing has been left undone to make Kephalo a safe anchorage. A complete net-guard stretched across the harbour has up to the present been effective in preventing submarine attack.

The strictest secrecy was maintained with regard to the new landing in Gallipoli, thus preventing anything but the vaguest rumours leaking out as to the point chosen for disembarkation. It was presumed that the Turks must have taken every possible protective measure to guard against surprise. I was very fortunate in being attached to the ship which the Admiral conducting operations had chosen as his temporary flagship.

It is difficult to give any idea of the strange feelings that possessed us as we crept through the darkness on the night of August 6, knowing that big events loomed ahead. Would it be a surprise to the enemy? Had they any information of our movements? A single bright light showing on the northerly end of Imbros looked suspiciously like a signal to the Turks, a simple matter when one realised that our bases in these islands were held entirely on sufferance and we had practically no [10]jurisdiction over spies. Our occupation of the various islands was somewhat Gilbertian; after the war between Turkey and Greece both parties claimed the islands in the Ægean, neither being in a position to hold them successfully. Consequently, when the Dardanelles operations commenced, we naturally decided to regard the islands as "No Man's Land," although the Greeks knew that, in the event of a successful campaign, we should probably hand them over to their keeping. It is certain that without them we could never have carried on the operations in this theatre of war.

We left the anchorage of Kephalo with every light obscured and silence enjoined, even white clothes and cigarettes being forbidden on deck. It was fortunately a dark night even for these parts. At slow speed with a picket-boat close on our quarter we crept across the twelve miles separating us from Suvla Bay, which by now was generally presumed to be the place chosen for what we hoped would be a surprise landing. Two cruisers, the Theseus and Endymion, carrying large numbers of men, and specially fitted with gangways over their sterns to allow the troops to walk down into motor-lighters, were sent on with destroyers towing motor-lighters full of troops to be at the point of [11]disembarkation at about 11.30 p.m. We on the flagship steered a slightly more northerly course, in order not to interfere with these vessels in the darkness, and arrived in Suvla Bay at about 12.30 a.m.

The fact that the landing had already begun was shown by desultory rifle-fire from the shore, but of so spasmodic a character that a feeling of hope arose that the surprise was complete. Impatience now became general for the first gleam of daylight. After an apparently endless wait the dawn began to make in the eastern sky, and there was enough light to get some idea of the general state of affairs.

On C beach the troops had landed from the cruisers and destroyers in the darkness with practically no opposition. A beautiful sandy shore, sloping at sufficiently steep an angle to allow the motor-lighters to beach without difficulty, facilitated the landing. The troops, dashing forward, were able to penetrate inland and drive the small bodies of Turks out of their trenches. They then advanced over the now dry salt lake some considerable distance.

On A beach things were not so successful. Here, a shallow ridge of sand, running parallel to the shore, held up three of the motor-lighters carrying some [12]1500 men at a point where wading was impossible, owing to the deeper water inside the ridge. Here the men were subjected to considerable rifle-fire from bodies of Turkish troops and suffered a number of casualties. Picket-boats, however, succeeded in taking them off and landing them on the beach.

By this time it was possible to see more plainly what was taking place. Two batteries of Turkish field-guns opened fire with shrapnel and high explosives on the landing-parties and on the three lighters which were firmly fixed on the sand reef. The lighters specially claimed the attention of the enemy's guns, doubtless under the impression that they still contained troops. Beyond the lighters large numbers of men could be seen filing along the beach, or forming up, and amongst these, large columns of sand and dust showed where the shells pitched, causing many casualties.

At about five o'clock an enemy aeroplane was sighted, but so occupied was everyone with the work in hand that practically no attention was paid to her; and shortly after, four large bombs were dropped in quick succession in the harbour, causing huge columns of discoloured water to rise, but doing no damage to the shipping, which by now had grown in numbers. Five fleet sweepers [13]arrived bringing large numbers of men, who were landed rapidly to support those already ashore, and as quickly disappeared into the scrub beyond the beach. The Talbot and Chatham were now busy with their 6-inch guns driving back those Turks who still endeavoured to oppose our landing. The Talbot by a few well-placed shots entirely disposed of a battery which had considerably annoyed us during the early part of the operations. It was impossible now to see exactly what was taking place, as the low-lying land, over which the troops were advancing, was hidden by sand dunes from the harbour.

By now large transports were arriving with more troops and stores, and a battery of field artillery was landed and quickly galloped into a position on Lalla Baba, where they could give good support to the advance.

A slight description of the country in which this attempt to straddle the peninsula was taking place may be of interest, as seen from the sea. On our left Suvla Point, with Nebruniessi Point to the right, formed a small bay known as Suvla Bay some mile and a half across. To the right of Nebruniessi Point a long gently curving sandy beach some four or five miles in extent terminated where the Australian [14]position at Anzac rose steeply to the Sari Bair range. Inside and immediately in front of us was a large flat sandy plain covered with scrub, while the dry salt lake showed dazzlingly white in the hot morning sun. Immediately beyond was Chocolate Hill, and behind this again lay the village of Anafarta some four miles from the shore. As a background, the Anafarta ridge ran from the village practically parallel with the sea until it took a sharp turn due west to Suvla Point, where it gradually sloped down to the coast. Beyond the plain in front of us a number of stunted oaks, gradually becoming more dense further inland, formed excellent cover for the enemy's snipers—a mode of warfare at which the Turk has become an adept.

By climbing into the foretop of the vessel, it was possible to watch the living cinema of battle. Glasses were necessary to distinguish the light khaki of our men against the scrub and sand. The troops marching in open order across the salt lake formed a most stirring picture as they crossed the unbroken surface of silver-white. Overhead shrapnel burst unceasingly, leaving small crumpled forms on the ground, one or more of which would slowly rise and walk shorewards, while others lay where they fell. Beyond this open space it became almost [15]impossible to follow the movements of the battle, but the continual rattle of musketry showed where the advance was proceeding into the more thickly wooded plain. Our hopes that the surrounding ridges would be taken before nightfall were unfortunately not realised. The enemy, though not in great strength to commence with, were continually reinforced, while the broken nature of the ground made anything like perfect cohesion amongst our various units extremely difficult. To make matters still worse, the enemy's shells caused dense bush fires, which, driven by the wind, burst into sheets of flame. Great difficulty was experienced in dealing with snipers. Officers and men were continually shot down, not only by rifle fire from advanced posts of the enemy, but by men and even women behind our own firing-line. The particular kind of tree in this part, a stunted oak, lends itself peculiarly to concealment, being short with dense foliage. Here, a sniper would lurk with face painted green and so well hidden as to defy detection. Others would crouch in the dense brushwood, where anyone passing could be shot with ease. When discovered, these snipers had in their possession enough food and water for a considerable period as well as an ample supply of ammunition. Although this seems a [16]murderous kind of warfare, there is no question as to the pluck of the sniper, of whatever nationality, for he has little chance of getting back to his comrades and small likelihood of quarter if caught.

Water, or rather the want of it, was a serious bar to our progress in the initial stages. Those who formed the first landing-parties carried provisions and water for forty-eight hours; but in a country of this nature and under a boiling sun it is naturally impossible to convince the young soldier fighting in a temperature he has never experienced before, of the necessity of husbanding his water supply. So it proved in this instance. The advanced troops were completely exhausted by thirst. Could this have been remedied at once it is certain a different tale would have been told.

The question which now arose amongst those who were conducting the naval side of the operations was, how long would the Turkish guns allow the shipping to remain in the harbour (it became a harbour, theoretically, as soon as the steamer detailed for the work had laid submarine defence nets).

The bay was now thickly crowded with shipping, including such tempting bait as big transports full of troops, store-ships, and every kind of vessel which goes to the support of an army. Yet, fortunately, we [17]were only subjected to intermittent shell-fire, the Turks probably experiencing some difficulty in getting guns into position in addition to those required against the troops.

It was not until the 12th August that any serious action was taken by the enemy against the ships in harbour. On that day the vessels inside the defence net consisted of a large monitor lying close in shore, several smaller monitors at intervals off the beach, the Cornwall, Chatham, and Swiftsure, and a number of transports and storeships. The Swiftsure was the flagship of Rear-Admiral Christian, who conducted the naval side of the operations.

Shortly after midday the Turks opened fire on the monitor Havelock. The range was good, but the first shells were ineffective, though they fell close round her. As she was lying at anchor, and things were becoming rather uncomfortable, she weighed and was just moving when a shell burst on the upper deck behind the funnel, without, however, doing serious damage. The enemy's gunners realising now that their chances of hitting the Havelock were small, turned their attention to the Swiftsure. The latter, surrounded as she was by picket-boats and lighters, found it difficult to get under weigh quickly. Several of us were standing on the quarter-deck [18]of the flagship when the shells began to come in our direction. The first shell pitched some fifty yards short; the next passed overhead, falling fairly close to our port side. They had our range to a nicety. The probability that the third would hit us caused a hurried exodus below deck, where, although the protection afforded was not great, one felt a sense of security which was perhaps more theoretical than practical. Almost immediately the heavy thud of a projectile outside the ward-room told us that our judgment was not far wrong. Fortunately this failed to explode, and was afterwards picked up on the net shelf. Another entered the ship's side close to the padre's cabin, and, going through three steel partitions, brought up in the petty officers' pantry, where a peaceful domestic was engaged in washing-up. Fortunately for him this also failed to explode. Immediately afterwards three high explosive shells came inboard on the upper deck, and bursting there killed 7 men and wounded 16. Curiosity in this case had overcome a sense of prudence, for they had been watching the enemy's attempt to drive us out of the harbour.

The numerous picket-boats, lighters, etc., had now left us, so we were able to get weigh on the ship. We slowly steamed in a circle without going [19]outside the defence net, in case a submarine might be lying in wait as part of a preconceived plan. The fact that we had moved from our former billet was sufficient to stop the enemy's fire, as practically all his guns were field artillery, making it almost impossible to follow a moving object with the accuracy of a naval gun.

It is not my intention to attempt any elaborate description of the land operations, as it was very difficult to obtain really reliable news. Moreover, after the first few days, the Turks had succeeded in bringing up a number of fresh troops and artillery, and were strongly entrenched. It was increasingly evident, therefore, that, unless a very large body of men could be brought up the advance had virtually ceased and resolved itself into a digging-in competition. Up till now the Turks had made no concerted effort to drive us out; but one night, at about eight o'clock, a heavy bombardment suddenly commenced on the left flank, which lasted about an hour and a half. The sky was lit by hundreds of bursting shrapnel, high explosives and star shells: the prelude, presumably, to an attack in force. From our position in the bay it certainly looked as if a big fight were in progress, and a great deal of speculation was rife on the ships in harbour as to the [20]outcome. About 9.30 a signal arrived from the Headquarters 9th Army Corps, saying "Situation well in hand." It appeared, for some reason unknown to us, that the enemy had entirely failed to follow up the bombardment and attack. Indeed, as far as could be ascertained, not a single Turk had left the trenches, and we afterwards learned from deserters that even flogging and threats had failed to move them.

After this, day succeeded day with a desultory artillery duel morning and evening, the afternoons being presumably spent by the Turks in a siesta. Little was accomplished by the artillery fire, beyond the annoyance caused by shells falling amongst the stores and dug-outs at the bases. It was astonishing to see high explosive shells bursting in what appeared to be crowded areas and to learn afterwards from the soldiers that comparatively few casualties had resulted. Certainly, at times, a shell would cause considerable damage, especially if it fell on rock or hard earth: one of these killed and wounded upwards of 100 mules, and another, which I saw, killed 9 men and wounded 7; but these were exceptions. The Red Cross dressing stations had been shelled in the early days of the landing, as, owing possibly to the restricted area held by us, or more [21]probably to carelessness and want of thought, large quantities of stores and ammunition were landed close to the dressing stations. These suffered considerably in consequence from shell-fire. This was not a deliberate act, as no nation could possibly have conducted warfare in a more above-board and clean-handed manner than the Turks. The fact that such qualities could be attributed to the Turk was a surprise to me, though naval officers generally have long regarded him as the gentleman of the Eastern Mediterranean. This is further borne out by his reported refusal to use poisonous gas when attacking.

On the afternoon of the landing the Turks sent in an emissary to say that the Red Cross stations would be respected provided no stores were landed in the vicinity. Also at a later date the Turkish Headquarters made a helio to the effect that they had seen tows of boats communicating between warships and the dressing stations. This they very naturally resented, and said it must cease or they would feel compelled to open fire. In another case a surgeon told me that the enemy had actually sent to apologise to him for the accidental shooting of one of his stretcher-bearers. All this is, of course, only what one would expect from a chivalrous enemy. So brutally, however, have many of the theoretical [22]usages of war been violated that the action of the Turk stands out in bright contrast, and shows that this much-maligned race retains a sense of honour which seems to be lacking in others who claim the right to lead the world in this direction.

The Turkish prisoners taken by us were few in number. Many were farmers whose one wish appeared to be to see the end of the war. After all, when one remembers that the Turk has always been friendly to the British, it is not surprising that in fighting against us he should still retain a good deal of his old feeling. At the same time he is fighting in defence of his own country, and is regarded by all who know him as never so effective as when on the defensive. All one hears and reads of dissension amongst the Turkish and German officers may be true, as no doubt the German officer has taken a high hand in his dealings with the Turkish Army. At the same time the Turk is not so blind but that he realises, to the full, the value of the German as a teacher of the latest methods and devices of warfare.

Shortly after my arrival I was appointed to a ship engaged in bombarding enemy gun positions and trenches off the left flank of the army at Helles. To those unacquainted with warships perhaps a short description of the ship may be of interest, though I cannot of course enter into an exhaustive account of our particular form of defence which has been evolved through the advent of the submarine. The ship I joined is known in the Navy, since her re-incarnation, as a "blister" ship. She belongs to the Blake and Blenheim type, which were in their day the finest cruisers turned out by any naval power; handsome vessels, good sea-boats, and generally a crack class; but on the outbreak of hostilities they were a back number and practically ready for the ship-breaker. One of the surprises of this war, however, has been the amount of active work done by the older vessels, many of them good enough ships, though not fit to [24]lie in the battle-line, but excellent for bombardment purposes, for which they have been extensively used. Amongst these the cruiser I have mentioned came in for special protective treatment. Since the German submarine had driven our battle fleet into protective harbours, and the Army must be supported at any cost, a scheme for rendering these vessels proof against the torpedo had to be devised. Torpedo nets had failed in the case of the Triumph, and were apt to render a ship extremely unhandy in the event of the enemy batteries successfully getting the range.

The first day on which the ship saw any action we left Kephalo at nine o'clock in the morning to relieve the Endymion, our sister-ship on the left flank, each of us doing forty-eight hours on patrol and forty-eight in harbour. I must say my feelings were somewhat strange at being actually on a war vessel for the first time about to come under fire.

Impressions of this kind have been described so often that I feel nothing in the way of a pen-picture can give readers any new idea of the sensation. My own feelings were a strange mixture of a desire to get under some really effective cover and a wish to [25]see the fall of our own shot on the enemy's position. Our first taste was at a range which enabled one to get a fair warning of the approach of the enemy's shell. One heard first the distant bang of the gun, followed almost immediately by a long whine which grew in crescendo until the shell hit the water with a loud plop. In the case of shrapnel this exploded generally very short of us, leaving a round ball of white smoke suspended in the air for some moments, the bullets generally striking the sea some fifty yards ahead of the burst. The shells which straddled the ship were the most trying, as the sound of a projectile passed right overhead, and seemed as if it must be coming inboard. The long range (most of the shell-fire being 12 or 15 pr.) made the danger problematical, as the angle of descent was very steep. On the other hand, should we be hit, the shell was likely to fall on our unarmoured decks. In the case of several ships comparatively small shells had caused damage in this way out of all proportion to the size of the projectiles: in one instance a shell came inboard on the Grafton between the foremast and funnel, and bursting there, killed 9 and wounded 17 men.

The general consensus of opinion on board was [26]that the Turks only fired when fired on, which went some way to allay apprehension. Our first day out certainly confirmed this idea, for it was not until we had fired a number of rounds that any reply came from the shore, and that of so desultory a nature as to cause us little worry. At about five in the afternoon one of our seaplanes came out to observe and spot our fall of shot; this was the only way in which any accurate results could be obtained. While off the coast we were practically at the disposal of the military, who informed us when any Turkish batteries caused them particular annoyance. They would then signal to us the position on which they wished the shells to be fired.

The procedure was of some interest, as the shooting which we were required to do was of a somewhat novel kind for naval guns. With very few exceptions, where the objective could be seen, the target was only one of many concealed batteries. On one occasion as many as 800 Turkish shells were fired in a comparatively short space of time from the Asiatic shore on to Helles beach, although the total casualties, due to the wonderful system of dug-outs, were only three mules killed and two men wounded.

The hour chosen for our practice on the enemy's gun emplacements was, as a rule, late in the afternoon, by which time the sun was directly behind us and showed up every formation of the coast. At about the time appointed one or other of the lookouts would report "Aeroplane in sight, sir," and shortly afterwards one shot would be fired, or possibly three, to give the aeroplane something to work on. The range, usually about 8000 yards, was arrived at by the navigator, who, knowing our own distance from the coast to a yard, would then use the squared map of the peninsula on which every known Turkish battery was marked, and add to it the distance inland of the particular battery, taking for a point of aim some feature on the land, the ship being stationary.

The most interesting place on the ship while firing was in progress was "Monkey Island." This is the platform above the chart-house used in ordinary times for navigation and from which a clear all-round view can be obtained. It was surrounded by a thick protection of canvas packed with cotton-waste, rope, and other odds and ends to render it proof at least against shrapnel and rifle bullets, whilst overhead a thick mat was suspended for the same purpose. It [28]is from this position that the directions are handed on to the guns by voice-pipe from the control on the foremast, where the gunnery lieutenant is stationed.

Soon after the first shot is fired, the tinkle of a bell can be heard. This is the telephone from the wireless-room, where the aeroplane's spotting correction has been received, and the Captain's voice is heard at the voice-pipe from the conning-towers to the fire-control, giving the gunnery officer the correction. Assuming the aeroplane's signal to have been, say, 200 short 50 left, the gunnery lieutenant then gives the corrected range via "Monkey Island" to the guns, or whichever particular gun he wishes to use. The message is handed on by a boy to the gun below, and there repeated by one of the gun's crew back to the fire-control in confirmation. A moment's pause, and the order "Fire" is again given. Immediately a sheet of bright orange flame, and an ear-splitting crash are followed by a vibrating rush of the shell through the air, gradually dying down to a distant sigh. Then just over our point of aim a dirty yellowish cloud rises slowly, showing roughly the spot on which our shell has fallen. At last, after possibly four or five shots, the aeroplane [29]makes the signal "O K," showing that one of our shots has got home in the gun emplacement, and rapid fire opens from all guns which bear on the side engaged.

An instance of the unfailing supply of the lighter side of things was afforded one day when the ship was under fire from Turkish batteries. Everyone was under cover more or less, though it is a very difficult matter to get men who have never been under fire to take cover adequately. The human is a curious animal when he wants to see what is happening, and, as a rule, it was not until a ship had been badly hit and men killed or wounded that the necessity to seek cover seemed to be taken to heart. On the occasion already mentioned the Turks were doing some very good shooting, and a fairly large high-explosive shell burst on the water close to us on the starboard side just abaft the bridge. A large number of shell fragments came inboard, scattering groups of men, who were watching events, without injuring any of them. Their hurried flight caused much hilarity amongst the gun-layers and others already in cover, but any sense of fear on the part of those so dispersed rapidly gave place to a desire to collect souvenirs in the shape of shell-splinters. A [30]piece of shell which has actually come aboard your own ship while you are in her possesses a value to the finder which is peculiarly personal. Consequently the fo'c's'le and waist of the ship immediately became a hunting ground for eager collectors; and as most people know the amount of gear on a ship's deck, it will be understood that there were possibilities of a find in a variety of places. However, the first men on the scene rapidly collected all that could be found, and a large number sought in vain for a memento of the occasion. Amongst these was a member of the crew whose late arrival precluded any chance of finding souvenirs, but whose brain was not slow in supplying a substitute for the much-sought-after booty. Every warship carries a blacksmith's forge, and scattered about in its vicinity are nearly always to be found a number of small pieces of iron of all shapes and sizes, many of them remarkably like shell-splinters. The late-comer quickly turned his attention to these, and, making a rapid collection of the most likely looking fragments, he joined the still eager searchers. Presently, as the enthusiasm waned for want of spoil, he produced a number of deadly looking fragments, some of which he gave to empty-handed shipmates, while others he parted with for [31]small sums. These are now probably looked upon in sundry homes as the "bit o' shell that nearly wiped out poor Bill."

I suppose active service always brings with it periods of dullness and monotony, when any little incident like the foregoing is welcomed with relief. Another event of this kind which seems to me worth recounting caused a good deal of amusement at the time.

On our ship there was a small coterie of non-executive officers, whose particular duties were not called into use when the ship was under fire. The novelty of being fired at having worn off, and the danger of unnecessarily exposing oneself realised, they decided, after interrogating sundry experts on the subject, that the safest place in the ship, short of the indignity of descending below the armoured deck, was the gun-room. We carried no midshipmen, so that the gun-room was occupied only by one or two warrant officers whose duty, during action, mostly lay on deck. It was here, therefore, that the aforesaid coterie gathered as soon as we came under fire, to indulge in a quiet game of bridge. The prolonged immunity of this particular spot from shell-fire had lulled into a sense of security any [32]feelings of apprehension as to the likelihood of a shell finding its way there, the more so as it was not only on the lower deck but on the disengaged side. But the joyful band of card-players received a severe shock. Firing had been in progress for some time, and a few shells of the enemy had pitched near the ship while a game of bridge was in full swing. Suddenly a terrific crash on the starboard side, followed by a big explosion, denoted the arrival of a shell in their immediate vicinity. It had penetrated the side exactly opposite the gun-room, and, bursting, fortunately in a store-room (thus to some extent localising the damage), hurled several large fragments through the open door into the midst of the players without actually touching one of them. The luckiest escape was that of an officer who was standing in the doorway at the time leaning with one hand high up on the side of the entrance. A fragment of shell passed beneath his arm close over the heads of the players and buried itself in the casing on the inside of the ship. The whole flat outside was filled with dust and débris, and it was some moments before the occupants could get sufficiently sorted out to realise that no injuries had been received. Needless to say, this rude disturbance [33]caused a somewhat hurried exit from the "safest" place in the ship, and great was the chaff which had to be endured by the erstwhile inhabitants, the more so as this was the only hit scored by the enemy on that day.

The work of the trawlers in the Dardanelles demands special mention. The men running these vessels are in the majority of cases elderly, and the ships themselves were never intended to come under fire; yet these men have constantly been in very hot places, and have gone there knowing what was in store for them.

The ships have been used for every conceivable kind of work. They have carried stores, troops, mails and munitions. They have been engaged in mine-sweeping, patrolling and towing nets. They have tackled the elusive submarine; in fact, they have done everything that can be thought of short of bombarding forts, and they would cheerfully take this job on if required. Here is the typical day of a trawler during general ferry work, on which I took passage.

We left Kephalo early in the morning, calling first at Anzac, then at Helles; from there to Rabbit [35]Island and Tenedos; back to Helles, and, if required, to Anzac again. Generally from Helles this trawler would go direct to Kephalo. The round is seventy odd miles. Every morning on starting, the skipper knew the ship would come under shell-fire at Anzac almost without fail, as the anchorage is commanded by the Turkish guns, and any sign of movement, or of ships arriving or leaving, invariably brought its accompaniment of shells. I gathered from him that this had been his daily lot for four months.

He was a fine type of North Sea skipper, and took everything as it came with a stoicism which was admirable. He didn't like it—nobody does; but it was his job, and there was an end of it!

The day on which I took passage with him was typical of all the others. We left Kephalo at seven in the morning, the sun well up and already hot, blue sky, blue sea and a very light breeze. Anzac, our first port of call, showed up clearly some twelve miles off, standing out, by reason of its distinctive character, from the rest of the coast. Rising between the flat sandy beaches—C beach and Brighton beach—it looked as if the Sari Bair range had suddenly been chopped off or slipped into the sea. Here were no foot-hills sloping gently to the coast, [36]but abrupt sandstone precipices looking very unfinished in the brilliant morning light.

The fact that our reception, of which I had already been warned, would be as usual, was borne out on nearing the coast. The Anzac water-steamer, lying some 3000 yards out waiting for lighters to come off, attracted the attention of the enemy. When we got fairly close to her we heard a distant bang, which told us the Turks were awake. Now a gun being fired at you is unmistakable and quite different from one of your own guns, though the latter may be much louder. In this case, although only a second or two intervened between the report and the splash of the shell, it gave time for speculation as to what was the enemy's objective. The shell fell about fifty yards short of the water-boat, and was followed immediately by another which straddled her, pitching about the same distance over. On this, she rapidly got under weigh and stood out to sea, followed by a number of rounds which were ineffective.

By this time we were close into Anzac beach, and had anchored preparatory to a picket-boat coming off to take our mails, etc. Four other trawlers lay close to us engaged on various duties. The Turks being baulked of their first quarry, now turned their attention to us, and it must be said that nothing is much [37]more unpleasant than to be confined in a very small vessel at anchor with no protection but the thinnest sheet-iron. Their first shot at us was shrapnel, and the range not bad. Shrapnel is, I think, the most spiteful sounding of all shells. The sharp report of the shell burst, followed by a kind of metallic whistle as the numerous bullets tear through space, being very unpleasant. However, after this trial-shot the enemy turned to high explosives, and one's feelings gravitated between hope that they would not hit us and wonder that they didn't. Some of them were certainly closer than I cared for, but having a camera and a feeling that, after all, things were very much in the hands of Allah, I thought the moment seemed opportune for a photograph. Being on the bridge at the time, I held my camera ready and was almost immediately rewarded by a high explosive pitching about thirty yards over us on the port side. There was no time to look in the finder, as the column of water thrown up by a shell subsides very quickly, so I simply pointed the camera at the spot, in the hope that somewhere on the plate there might be a result.

By now we were under weigh again, after handing our mails over to the shore-boat, and the other trawlers were heaving up their anchors. The Turks, [38]realising that little was to be achieved, ceased fire, except for an occasional shrapnel to hurry us on our way.

Anzac, as we left it with the morning sun right overhead, looked a most forbidding spot. The deep, gloomy shadows of the gullies were accentuated by the brilliant sun lighting up each knife-edged ridge. One could picture the scene on that morning of April 25, when the gallant troops from Australia and New Zealand made their wonderful landing on this inhospitable shore.

Our course, after standing well out to avoid the enemy's guns, now lay to the southward, parallel to the shore, Helles being our next calling-place. At this time the only parts of the peninsula occupied by the Allies were Anzac and Helles. Seeing the great extent of country held by the enemy, it was brought home to one what very small holdings were ours after months of desperate fighting. Here and there on the way were monitors and destroyers occasionally firing on enemy gun positions, or on any movements of troops that could be seen. Opportunities for the latter were rare, the nature of the ground rendering it easy for the enemy to keep entirely out of sight. Nearer the end of the peninsula was my own ship, [39]the Theseus, one of the flanking ships patrolling on the left of the troops at Helles. Shortly after we rounded Cape Tekeh and anchored, where again a picket-boat came alongside, bringing details for the island of Tenedos and taking off the mails we had brought. Meanwhile, a certain number of shells were falling on the base camp, and occasionally an "over" would drop among the shipping; but nothing came near enough to worry us.

The base camp from the sea gave an impression of a burnt-up waste. The long occupation had removed every sign of vegetation, and nothing remained but yellow sand and clouds of dust driving seaward in the freshening breeze.

The place was teeming with life, apparently oblivious of the falling shells. The whole face of the sand-cliff was honeycombed with dug-outs and roads cut for transport, and the beaches were covered with the endless paraphernalia of a camp in war-time.

Our next place of call was Rabbit Island, to the south of Helles. As we left the end of the peninsula, a wonderful panorama could be obtained of the whole position. Achi Baba loomed over all, while to the right Seddul Bahr, the entrance to the Dardanelles, and the Asiatic shore showed clearly. It was here [40]that the disastrous attack of April 18 took place, which showed us the futility of forcing the Narrows without an adequate landing force acting in co-operation.

Our stay at Rabbit Island was short. Only one or two ships lay there. The island itself is a barren hummock of very small extent, and of little value except for the special use to which it is being put. Some ships' boats came off for fleet letters and a few mails, after which we took our departure for Tenedos.

Tenedos, one of the most flourishing of the islands in the vicinity of the Dardanelles, is used by us and the French as an aeroplane base. The picturesque harbour is surrounded by quaint buildings, with an ancient fort dominating the whole. A short stay here completed our business. The return journey to Helles and Kephalo was uneventful. True, our reception at Helles was disturbed somewhat by a 6-inch shell, which fell immediately astern of us as we were approaching our anchorage. Fortunately, this was a solo, for, though we momentarily anticipated the usual chorus, nothing further occurred to disturb our peace of mind. None the less, I must say I looked forward to an early departure; but this [41]was disposed of temporarily by the arrival of a picket-boat with orders to wait for two naval officers. However, this only delayed us some twenty minutes, when we took our leave of Helles, arriving at Kephalo at dusk.

In the various landings in Gallipoli it naturally came about that the Navy, after the actual disembarkation of the troops, had a great deal of work to do in connection with the incessant stream of material, stores, etc., and this necessitated more or less permanent beach-parties, composed of bluejackets who lived and had their being with the soldiers at the base camps. A naval captain, as beach master, one or two lieutenants and midshipmen to run the picket-boats, and a number of seamen ratings comprised these parties. It was their duty to see to the handling of the transports, landing of stores, and the various other jobs which come natural to a sailor where sea and shore meet. The bluejacket takes a different view of life from the soldier. This is not surprising, for his mode of life and training is peculiar to the Navy. Certainly the sailors on the beaches were generally regarded with considerable interest by their military companions. A Major with whom [43]I came in contact gave me an entertaining account of the naval camp situated close to his dug-out. It appeared at the commencement of activities on shore that the collecting of souvenirs, in the shape of shell-splinters, shrapnel cases, or anything of this nature, was greatly in vogue, and developed into something of a fine art. As a rule, when the Turks began to shell the beaches, every one whose occupation would allow, dived into his dug-out and remained there until the firing had ceased. The sailors' camp was no exception to this; but however hot the fire, one or more heads would invariably be seen projecting from the entrance to the dug-out somewhat like a tortoise looking out from his shell. An instinctive knowledge seemed to be possessed by the owners of the heads where a shell in flight was likely to pitch. The moment the explosion had taken place a number of men carrying spades would emerge from the dug-outs, race across the sand and scrub to the spot and begin a furious digging competition for fragments.

Sailors have been trained from youth up to regard anything and everything, from a piece of string to a traction engine, as likely to be of use at some time or other. Consequently their dug-outs were museums of all the flotsam and jetsam which a military base [44]provides in war-time, and, I imagine, a good deal which does not come into this category.

The Major, who seemed so entertained with the beach-party and its doings, told me that immediately after the Suvla Bay landing, and during the advance on the left flank, it was his duty to take charge of a considerable amount of unused Turkish field-gun ammunition amounting to some 700 rounds. Now there is probably nothing which appeals to the collector of battlefield souvenirs so much as a complete cartridge case and shell. This makes a beautiful trophy when polished and gives the possessor somewhat the same feeling as a schoolboy who obtains a rare unused stamp which he knows to be genuine.

The ammunition in question was to be sent down to the base, where instructions would be given as to its disposal. Oddly enough, soon after arrival it appeared to be slowly and steadily diminishing, and reports reached the Major of dark figures having been seen flitting about the store at night. On his return to the base the number of shells had been reduced to some 300, and for a long time their disappearance was wrapped in mystery. One day, however, when on his way to call on a brother officer, the Major's direction lay through the beach-parties' camp. Whilst passing one of the dug-outs he was surprised to hear [45]a sharp explosion and to see four sailors hurl themselves into the open through the diminutive doorway. One had a somewhat blackened face and very little eyebrows or front hair, whilst the others were in the evident enjoyment of a good joke. Inquiries elicited the fact that the hurried exit was caused by the premature explosion of a shell-fuse which was being coaxed into yielding up its active properties with the aid of a jack-knife or some similar weapon. A closer inspection of the dug-out disclosed the fact that amongst many other trophies of war a considerable number of the missing shells played a large part in the decoration of the interior. Most of them had already undergone the aforesaid operation, and, with charges drawn, now stood ready to be sent home, when opportunity should offer, to grace the parlour mantelpiece.

In the matter of clothes the sailors showed a marked disinclination to wear anything provided for them. They were supplied with khaki, as white would be far too conspicuous; but, being ashore, and feeling, I suppose, something of a sense of relaxed discipline, it was almost impossible to get them to wear the clothes served out. Consequently you saw the strangest collection of garments being worn in the beach-parties' camp. An order to wear [46]the clothes provided would produce a return to regulation dress for a day, or possibly two, after which most of the men would again be wearing the kit which suited their particular tastes. It was found hopeless to try and enforce the rule. After all, in a case of this kind, and under the peculiar circumstances, it is perhaps better to indulge a man's fancy as long as it does not affect the work in hand and keeps him cheerful and happy.

A naval officer, whose duties lay on shore, told me this story one day which I think is good enough to relate.

He was outside his dug-out one afternoon and chanced to see two men passing in strange raiment. The combination of gait and the fact that both were wearing navy flannels told him at once that they were blue-jackets. Anxious to know what their special mission might be, he stopped and questioned them.

"Where are you going?"

"Motor-lighter K—, sir."

"Do you belong there?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then what are you doing here?"

"Well, sir," (hesitating) "we've just been up to the trenches."

"Were you sent there with orders?"

"Er—no, sir."

"How long have you been up there?"

"'Ow long, sir?" (then to companion) "When was it we went up, Bill?" (indistinct murmurs from diffident comrade—then to Captain) "I should say about four days, sir."

Finally the Captain ordered them down to a picket-boat in which he was about to visit the flagship, and they were put in the midshipman's charge under arrest. On the way out the Captain heard the two adventurers discussing their detention with some bitterness, always ending with the same refrain, which was repeated several times, thus: "Fine thing, this—under arrest. Well I'm ——! And they treat yer like a gentleman in the trenches—treat yer like a gentleman, I say."

It is difficult to imagine the point of view of men leaving the trenches with regret.

I believe I am right in saying that at the original landing at Helles many blue-jackets in charge of the landing-parties, whose boats had been sunk by the terrible fire, though they themselves escaped uninjured, joined with the soldiers in the advance on bare feet and with boat-hooks for weapons.

Here is an incident which came under my [48]personal notice, and though not really belonging to this chapter on beach-parties is nevertheless indirectly connected with the subject. It serves to illustrate the humorous spirit obtaining in the fleet, and occurred on a ship to which I was attached for some time. Our gunner, a man who had seen a great deal of service in almost every part of the world, was blessed with a large sense of the ridiculous. Now, the ship's carpenter seemed to possess an extraordinary attraction for shells, inasmuch as in whatever part of the ship he happened to be when we were under fire a shell invariably seemed to arrive in his close vicinity. This had happened so often that it got on his nerves. It occurred to the gunner that the shining hour might be improved by a little gentle attention on his part. It must be understood that what he did was done entirely to amuse himself and not from a wish to play to the gallery. One day, when several shells had fallen near us and to which we were not replying at the time, he ensconced himself behind an iron door leading from the battery on to the quarter-deck, which door was standing open at right angles to the doorway itself. Having provided himself with an iron bar, he kept vigil there in the hope that an occasion might arise which would take the carpenter [49]past his hiding-place. His wait, though long, was not unrewarded. The unwary carpenter came along the battery and out on to the quarter-deck, and at the moment of passing the gunner the latter delivered a tremendous blow on his own side of the iron door with the bar. The effect on the carpenter exceeded the gunner's wildest dreams, and caused infinite amusement amongst those of us who witnessed the incident, for we had been wondering what could be the meaning of the gunner's manœuvres.

It is, of course, a debatable point in this war, the first in which submarines have played a large part, to what extent they have justified their existence. Certain it is that as a moral force they are in a very strong position. Our own main battle-fleets have had to take very complete measures for protection against this form of attack. Any excursions to sea must always be done at high speed with an advance guard of destroyers and other light craft, though there is consolation in the fact that the fleet of the enemy have chosen to remain in more or less land-locked harbours with elaborate boomed defences. At the same time it is certain that the war at sea cannot be brought to a final end by the submarine, but must eventually be settled by the Capital ship.

The German submarines have had greater opportunities of paring down our Navy than we theirs. This applies especially to the early days of the war, when, owing to the total unexpectedness of the [51]upheaval, before experience had taught us how to deal with these unseen craft, they failed entirely to achieve anything that caused us alarm from a military standpoint. A few ancient cruisers fell to them, three of which, the Aboukir, the Hogue, and the Cressy, were so destroyed while indulging in a perfectly human desire to save life. All the ships so sunk were easy targets owing to slow speed. So far not one really fast modern vessel has been sunk by this form of attack.

If it could ever be known, which I fear is impossible, how many torpedoes have been fired at warships without taking effect (and the number is large), it would only go to show the difficulties encountered by the submarine and the immunity of the fast vessel. Add to this the large number of enemy submarines destroyed, nearly all by means evolved since war began (a period notoriously difficult in which to carry out experiments), and it is only reasonable to presume that, when times of peace come again, it will not be long before means are arrived at which will render surface vessels almost entirely immune from this form of attack.

Everyone is agreed that one of the brightest spots in our campaign in the Dardanelles has been supplied by the British submarines. If there are still people [52]at home who ask what the Navy is doing, one can point to these vessels as an example of what the whole Navy would do had they any scope in which to exercise their activities.

But we are dealing with an enemy who feels that he has nothing to gain and everything to lose by seeking an engagement. The impossibility of forcing his stronghold must be obvious to the least enlightened.

Our submarines out here have penetrated what most naval men would have declared to be an impassable barrier until it became an achieved fact. Think of the obstacles their crews have surmounted: rows of mines susceptible to the lightest touch, nets completely across the Narrows, and last, but not least, a strong current flowing seawards. Only then can you begin to realise the difficulties and dangers in endeavouring to gain an entrance into the Sea of Marmora and the main sea route for the Turkish water-borne supplies. The following signal, typical of many others, "E— arrived in Sea of Marmora without trouble, torpedoed a steamer in False Bay on her way," furnishes an indication that these desperate ventures are undertaken as a matter of course.

I met Commander Nasmith one afternoon at [53]Kephalo. He had just returned from an aeroplane flight up the Narrows after an investigation of the net defence placed across at that point to prevent submarines from penetrating into the Sea of Marmora. He did not seem very much impressed, and his judgment was justified next day when he took E11 through the defences and arrived in Marmora without mishap. The train-like regularity with which our submarines have accomplished this task is apt to make the venture appear commonplace to the newspaper reader, who may imagine that there is some easy road which, when once found, is plain-sailing. Nothing could be further from the truth. Every submarine that goes up does so with the full knowledge of the dangers to be faced, and the occasional loss of one of them shows the perils incurred.

In the early stages of the operations the net across the Narrows could be negotiated by diving under it; but, on a subsequent occasion, a submarine returning to the open sea found that the Turks had placed a deeper net in position. This particular submarine fouled the net at a depth of over one hundred feet, and was actually hung up by stout wire for upwards of fifteen minutes. It is impossible to imagine anything more likely to unnerve [54]men than to be caught like herrings in a net below the surface, and actually to hear, as they did, hydrostatic bombs exploding around them. The Turks would know, of course, by the agitation of the net above, that a submarine was caught; however, by going astern and then ahead, and allowing her whole weight to come on the net, the vessel broke through and returned in safety.

Many of our submarines after penetrating to the Sea of Marmora have made protracted stays of twenty-eight to thirty days, which is the more astonishing when one realises the cramped conditions and general discomfort when living on one of these boats for any length of time. I think it may be said that the Turks have ceased to regard the sea route as a means of supplying their troops with any degree of safety, the number of transports sunk being very large, including war vessels. One of the most successful pieces of work accomplished at the time of the Suvla Bay landing was the sinking of the Kaiserin Barbarossa by a British submarine. This ship had formerly belonged to Germany, but was purchased from them by Turkey. She was sent down from Constantinople to take position off Gallipoli or thereabouts with a view to indirect fire over the land with her 11-inch guns, of which she possessed [55]eight. She was also reported to be carrying large quantities of ammunition for the land forces. One can well imagine, therefore, the enthusiasm with which the signal of her sinking was received. Undoubtedly our ships and land-force thus escaped what might have been a severe menace, while the effect on the enemy was evidently salutary, as no further attempt was made to dispatch a war vessel with guns of heavy calibre to co-operate with their army.

Possibly at some future time a fuller description may be written when all the facts become known of the adventures of our submarines in this inland sea. These should certainly supply the historian with some of the most romantic episodes of the war.

The handling of wounded in the Dardanelles has been a difficult proposition, which the nature of the country has not tended to lessen. The injured men have to be taken off the shore by small boats and then transferred to hospital ships.

These ships are obliged to lie off some distance clear of rifle-bullets and shell-fire. Even then, several cases have occurred of men already wounded receiving further injury through stray shots reaching the ships.

A patient was sitting on his cot preparatory to turning in, when a bullet entered the open port and passing through two thicknesses of his pyjamas, buried itself in the deck. A nursing sister standing near at the time was relieved to see the man laughing and holding out his coat for her to examine. These occasional missiles were not fired intentionally at the hospital ships, but came over from trenches running parallel to the shore.

In most cases the ships lay out a mile or more. The first batch of wounded I saw came off after the landing at Suvla Bay. They arrived alongside us in a ship's barge towed by a picket-boat. They had been wounded during the night, and presented a sad spectacle, lying in the boat in every conceivable attitude with bandages through which the blood was soaking. Some of them were oblivious of everything, and wore a pathetically dazed look. Others not so badly injured seemed mildly interested in events around them, while the still lighter cases waved to us and appeared quite cheerful. The lightly wounded soldier is probably the happiest of all. He is out of the inferno of battle and is fairly certain of return to health and strength.

Those wounded among the first parties landed on an enemy's coast are, generally speaking, bound to undergo the greatest hardships. This specially applies to the Dardanelles. At Suvla Bay the suffering caused was added to by the shortage of water. The shore to which the wounded were brought was entirely devoid of shade, and the blazing sand was intensified by the heat of the sun. Operations on serious cases were performed with the greatest difficulty, and the shallow water close inshore made it impossible for the steam-cutters [58]to bring their tows of boats very near. The tows had, therefore, to be rowed to the beach by three or four sailors; the wounded were placed in them and rowed off again to the cutters.

An undertaking of this kind takes some considerable time when large numbers of sufferers are continually arriving. Consequently the dressing stations rapidly became congested, and it was some days before matters could be reduced to smooth working.

As soon as sufficient material had arrived, pontoon piers were built to allow the steam cutters to come right alongside.

The drinking-water difficulty was remedied to a large extent a day or two after the landing. War vessels in the harbour using their distilling plants were able to cope with the demand. Lighters, boats with canvas tanks, and in fact anything that would hold water were requisitioned.

These were towed as close inshore as the depth would allow, and connected with the beach by pipes. Each lighter carried a portable fire-engine for pumping purposes. This supply greatly alleviated the sufferings of the wounded. A severely injured man may be deadened to a sense of bodily pain, but thirst, which is scarcely ever absent, is the hardest to bear.

The amount of sickness among the troops in the Dardanelles far exceeds in proportion that of any other theatre of war. The reasons are not far to seek: want of proper rest, lack of really good water, and, worst of all, innumerable flies. This latter pest is the cause of much sickness, and is a most difficult problem to deal with. One must also take into account the intermittent shell-fire on the bases. This, while it tries the strongest nerves, at the same time tends, through custom, to make men regardless of danger.

A large number of hospital ships are naturally required to carry the sick and wounded. As far as can possibly be arranged, one of them is always lying off each base, so that immediately a ship is filled and proceeds to her destination her place is taken by another.

The carrying capacity of each vessel varies, though the smaller ones can accommodate even between two and three hundred; the mighty Aquitania, however, takes as many as four thousand.

Most of the light cases are conveyed to the islands of Mudros and Lemnos, while the serious ones are taken to England.

The most touching sights are the small cemeteries dotted about near the shore. On each grave is a [60]rough wooden cross, erected by loving comrades, and bearing the name and regiment of the dead hero. There seemed to me to be something infinitely sad at the thought of these men, who had given their all, sleeping a last sleep so far from the country they loved.

CAPE TEKEH Clouds of Sand blowing Seawards A

A SS RIVER CLYDE HELLES ACHI BABA B

B ENTRANCE TO DARDANELLES ASIATIC SHORE C

C ENTRANCE TO DARDANELLES ASIATIC SHORE KUM KALI

THIS PANORAMA READS FROM TOP TO BOTTOM.

THUS:—A.A.—B.B.—C.C.

SHELLS FALLING ON THE BASE CAMP AT HELLES.

These shells come from concealed guns on the slopes of Achi Baba, and from the Asiatic batteries. While causing much hindrance to the work on the beaches, at the same time the casualties are light, due to the wonderful system of dug-outs, the men taking shelter immediately firing begins.

OFF THE LEFT FLANK AT HELLES.

Achi Baba shows beyond the coast-line, and from this point of view is disappointing when seen for the first time. To the right and on the cliff is a brown patch extending from top to bottom, known as Gurka bluff, while immediately to the left of this is a zigzag line of trenches showing the northerly limit of our gain in this area.

MONITORS SHELLING YENI SHER VILLAGE AND ASIATIC BATTERIES.

The shell-bursts from these vessels on a still day were a wonderful sight. The beautiful shapes of the dense masses of smoke resembled cumulous clouds, hanging as they did for a long time before dispersing.

FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN SHELLING ACHI BABA.

This vessel was often engaged in firing on the enemy's gun positions, her salvoes of high explosive shells making a wonderful picture as they burst.

FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN'S 12-In. SHELLS BURSTING ON WESTERN SLOPES OF ACHI BABA.

This drawing was made from H.M.S. Theseus, with the aid of field-glasses. It seemed impossible for anything to live as one watched the tremendous explosions of these heavy shells.

BALLOON-SHIP HECTOR WITH KITE BALLOON UP, "SPOTTING" OFF THE LEFT FLANK.

The observers in the Balloon are able by their altitude to see the Turkish gun emplacements and to correct by signal to the ship firing the fall of her shot. These Balloons are very stable even in high winds. Up to the present they have escaped any damage despite attempts of every kind by the enemy.

LANDING AT "A" BEACH, AUGUST 7, 5.30 A.M.

A number of fleet boarding steamers took the troops close inshore, whence under the covering fire of warships they were conveyed in motor lighters. Three of these lighters can be seen in the middle distance, where they had grounded on a ridge during the night. Practically all the troops were removed to shore by ships' boats before daylight. The lighters then came under a heavy shell-fire, the enemy doubtless under the impression that they still contained men.

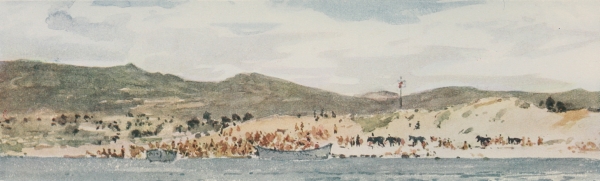

TROOPS LANDING AT "C" BEACH, AUGUST 7.

These troops were supporting the night-landing previously effected. A number of casualties were caused by bombs dropped from a hostile aeroplane and by Turkish shells.

"C" BEACH, AUGUST 8.

This beach was extensively used for landing stores and ambulance wagons. In the distance can be seen the Sari Bair range, which runs down to the Australian position at Anzac.

DRESSING STATION—"A" BEACH.

It was here that the largest number of wounded were brought immediately after the landing. The drawing shows the station as it appeared about a month afterwards.

SHIP'S BOATS GOING OFF TO A HOSPITAL SHIP WITH WOUNDED.

The shallowness of the water close inshore made it no easy matter to get the wounded away. Ship's boats were rowed close in, and the wounded were taken in tow by picket-boats, whence they were towed off to the hospital ships.

H.M.S. TALBOT IN SUVLA BAY SHELLING ENEMY RIDGES AT DUSK.

The effect of this vessel's lyddite bursting was very fine, an interesting contrast to this being the flash of her guns which showed a pale lemon colour in the approaching dusk.

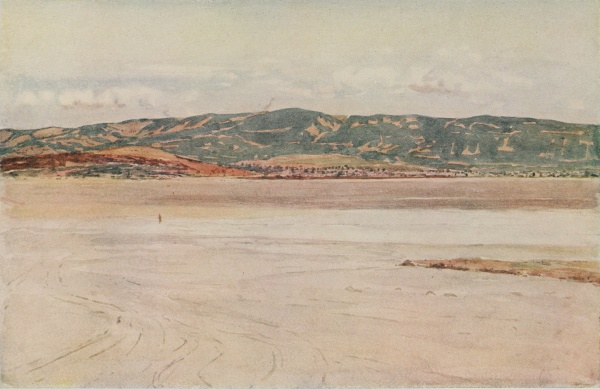

SALT LAKE AND CHOCOLATE HILL.

This lake, dry in summer, is hard clear sand, dazzlingly white in sunlight. It was over this that the troops advanced to the attack on Chocolate Hill, on August 7. In the distance is Sari Bair, the highest point of the range, running down to Anzac on the right.

LALLA BABA.

This position was continually under fire from shrapnel and high explosive shells. These frequently burst among the stores and material on the beach at the foot. Practically no part of the coast held by us is free from enemy shell-fire.

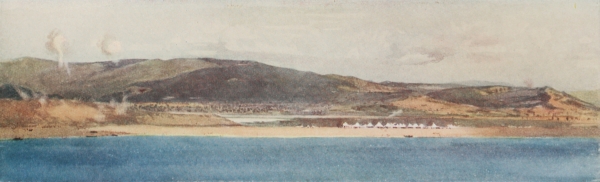

LOOKING TOWARDS THE VILLAGE OF ANAFARTA.

Lalla Baba is to the left, Salt Lake behind it, a small portion of the latter just on its right. Chocolate Hill is the small hill in the middle distance. Immediately to its right are the "W" hills. The village of Anafarta can be seen on the distant ridge in the right centre of the drawing.

H.M.S. SARNIA LANDING TROOPS IN SUVLA BAY.

This drawing was made some days after the actual landing. This ship is one of the vessels which took part in the operations at daybreak on August 7.

SALT LAKE FROM CHOCOLATE HILL.

This sketch, made from a dug-out on Chocolate Hill, shows the position when looking back over the dried-up Salt Lake. At the foot of the hill can be seen the partially burnt-up shrub, while the markings on the lake are caused by ambulance-wagon tracks and other traffic. To the left is Lalla Baba with Suvla Bay in the centre, and in the extreme distance the island of Samothrace.

TRANSPORTS UNDER SHELL-FIRE—SUVLA BAY.

The transports and store-ships frequently came under fire from the Turkish guns. The fact that few casualties were occasioned shows the enemy's gunnery not to have been very accurate.

SUPPORTING SHIPS AT THE SUVLA LANDING.

These war-vessels were used to cover the advancing troops, or to shell any bodies of Turks which could be seen.

ANZAC.

This sketch was made to the south'ard, and shows the dug-outs and some of the roads made since the occupation. The highest point is Sari Bair.

ANZAC.

This is the position at which the Australians and New Zealanders made their magnificent landing in the dawn on April 25. The drawing gives some idea of the terrible nature of the coast stormed by these gallant troops.

MOTOR LIGHTERS.

These lighters have been extensively used in landing troops from the transports. They have proved invaluable, being capable of taking as many as 500 men at one time.

SEAPLANE BASE.

A general view of the Seaplane base camp from a hill close by. On the left of the sand ridge is a salt-water lagoon, while in the far distance is the Gallipoli peninsula.

SEAPLANES AT KEPHALO.

The seaplanes in the Dardanelles have done much excellent work, and are extensively used in observing for the ships engaged in bombarding Turkish gun positions.

SUBMARINE E11 AT KEPHALO.

The vessel commanded by Commander Nasmith, V.C., which penetrated the Narrows and arrived off Constantinople, causing the greatest consternation there by sinking several vessels off the city and one actually alongside the quay.

HOSPITAL SHIPS AT KEPHALO.

The less serious cases among the wounded were brought from the mainland by hospital carriers and landed at rest camps in the island.

FRENCH FLAGSHIP SUFFREN.

Carrying the flag of the Contre Amiral Guepratte. This is the vessel shells from which are shown in a previous drawing.

HOSPITAL SHIP AQUITANIA.

The enormous bulk of the Aquitania was an outstanding feature in the harbour. The smaller hospital ship alongside is handing over serious cases to be sent back to England.

SUBMARINE E2 RETURNING FROM THE SEA OF MARMORA.

Submarines always receive a great ovation from vessels of every nationality in harbour on their return from raids in the Sea of Marmora.

MUDROS HARBOUR.

In the centre of the drawing is H.M.S. Glory. To the left are some of the French ships; while the Russian cruiser Askold can be seen on the extreme right.

HOSPITAL SHIP AQUITANIA AT MUDROS.

Some idea can be gained of the size of this vessel by the collier of 8000 tons lying alongside. The Aquitania has a carrying capacity of upwards of 4000 wounded.

Printed in Great Britain by

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited.

BRUNSWICK ST., STAMFORD ST., S.E.,

AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

Minor punctuation and printer errors repaired.