| Number 30. | SATURDAY, JANUARY 23, 1841. | Volume I. |

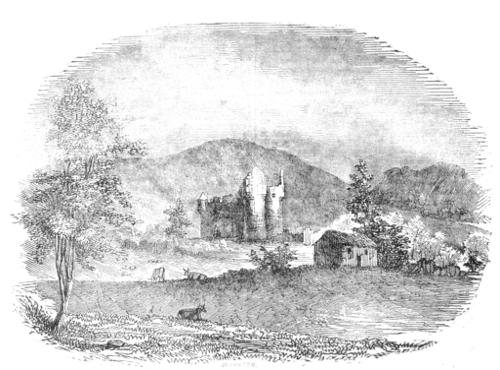

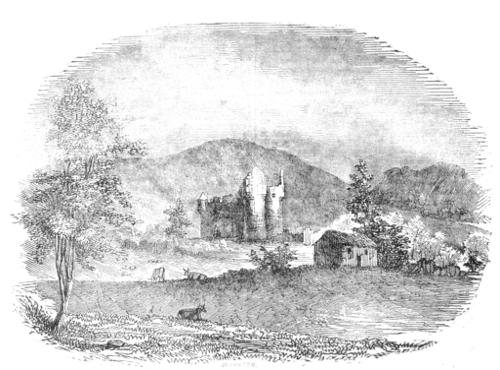

The Castle of Monea or Castletown-Monea—properly Magh an fhiaidh, i.e. the plain of the deer—is situated in the parish of Devinish, county of Fermanagh, and about five miles north-west of Enniskillen. Like the Castle of Tully, in the same county, of which we gave a view in a recent number, this castle affords a good example of the class of castellated residences erected on the great plantation of Ulster by the British and Scottish undertakers, in obedience to the fourth article concerning the English and Scottish undertakers, who “are to plant their portions with English and inland-Scottish tenants,” which was imposed upon them by “the orders and conditions to be observed by the undertakers upon the distribution and plantation of the escheated lands in Ulster,” in 1608. By this article it was provided that “every undertaker of the greatest proportion of two thousand acres shall, within two years after the date of his letters patent, build thereupon a castle, with a strong court or bawn about it; and every undertaker of the second or middle proportion of fifteen hundred acres shall within the same time build a stone or brick house thereupon, with a strong court or bawn about it. And every undertaker of the least proportion of one thousand acres shall within the same time make thereupon a strong court or bawn at least; and all the said undertakers shall cause their tenants to build houses for themselves and their families, near the principal castle, house, or bawn, for their mutual defence or strength,” &c.

Such was the origin of most of the castles and villages now existing in the six escheated counties of Ulster—historical memorials of a vast political movement—and among the rest this of Monea, which was the castle of the middle proportion of Dirrinefogher, of which Sir Robert Hamilton was the first patentee.

From Pynnar’s Survey of Ulster, made in 1618-19, it appears that this proportion had at that time passed into the possession of Malcolm Hamilton (who was afterwards archbishop of Cashel), by whom the castle was erected, though the bawn, as prescribed by the conditions, was not added till some years later. He says,

“Upon this proportion there is a strong castle of lime and stone, being fifty-four feet long and twenty feet broad, but hath no bawn unto it, nor any other defence for the succouring or relieving of his tenants.”

From an inquisition taken at Monea in 1630, we find, however, that this want was soon after supplied, and that the castle, which was fifty feet in height, was surrounded by a wall nine feet in height and three hundred in circuit.

The Malcolm Hamilton noticed by Pynnar as possessor of “the middle proportion of Dirrinefogher,” subsequently held the rectory of Devenish, which he retained in commendam with his archbishopric till his death in 1629. The proportion of Dirrinefogher, however, with its castle, was escheated to the crown in 1630; and shortly after, the old chapel of Monea was converted into a parish church, the original church being inconveniently situated on an island of Lough Erne.

Monea Castle served as a chief place of refuge to the English and Scottish settlers of the vicinity during the rebellion of 1641, and, like the Castle of Tully, it has its tales of horror recorded in story; but we shall not uselessly drag them to light. The village of Monea is an inconsiderable one, but there are several gentlemen’s seats in its neighbourhood, and the scenery around it is of great richness and beauty.

P.

Many of my readers will doubtless recollect that in a paper on “Animal Taming,” which appeared some weeks back in the pages of this Journal, I alluded slightly to the charming of animals, or taming them by spells or drugs. It is now my purpose to enter more fully upon this subject, and present my readers with a brief notice of what I have been able to glean respecting it, as well from the published accounts of remarkable travellers, as from oral descriptions received from personal friends of my own, who had opportunities of being eye witnesses to many of the practices to which I refer.

The most remarkable, and also the most ancient description of animal-charming with which we are acquainted, is that which consists in calling the venomous serpents from their holes, quelling their fury, and allaying their irritation, by means of certain charms, amongst which music stands forth in the most prominent position, though, whether it really is worthy of the first place as an actual agent, or is only thus put forward to cover that on which the true secret depends, is by no means perfectly clear.

Even in scripture we find the practice of serpent-charming noticed, and by no means as a novelty; in the 58th Psalm we are told that the wicked are like the “deaf adder that stoppeth her ear, which hearkeneth not unto the voice of the charmer, charm he never so wisely!” And in the book of Jeremiah, chap. viii, the disobedient people are thus threatened—“Behold, I will send serpents, cockatrices, among you, which will not be charmed.” These are two very remarkable passages, and I think we may, without going too far, set down as snake-charmers the Egyptian magi who contended against Moses and Aaron before the court of the proud and vacillating Pharaoh, striving to imitate by their juggling tricks the wondrous miracles which Moses wrought by the immediate aid of God himself. The feat of changing their sticks into serpents, for instance, is one of every-day performance in India, which a friend of mine has assured me he many times saw himself, and which has not been satisfactorily explained by any one.

The serpent has long been an object of extreme veneration to the natives of Hindostan, and has indeed, from the very earliest ages, been selected by many nations as an object of worship; why, I cannot explain, unless it originated in a superstitious perversion of the elevation of the brazen serpent in the wilderness by Moses. In India the serpent is not, however, altogether regarded as a deity—merely as a demon or genius: and the office usually supposed to be peculiar to these creatures is that of guardians. This is perhaps one of the most widely spread notions respecting the serpent that we are acquainted with. Herodotus mentions the sacred serpents which guarded the citadel of Athens, and which he states to have been fed monthly with cakes of honey; and adds, that these serpents being sacred, were harmless, and would not hurt men. A dragon was said to have guarded the golden fleece (or, as some think, a scaly serpent), and protected the gardens of the Hesperides—a singular coincidence, as it is of gardens principally that the Indians conceive the serpent to be the guardian.

Medea charmed the dragon by the melody of her voice. Herodotus mentions snakes being soothed by harmony; and Virgil, in the Æneid, says (translated by Dryden),

Even our own island, although serpents do not exist in it—a blessing for which, if we are to put faith in legendary lore, we have to thank St Patrick—has numberless legends and tales of crocks of treasure at the bottom of deep, deep lakes, or in dark and gloomy caves, in inaccessible and rocky mountains, guarded by a fierce and wakeful snake, a sleepless serpent, whose eyes are never closed, and who never for a second abated of his watchful care of the treasure-crock, of which he had originally been appointed guardian;[1] and, further, we are told how the daring and inventive genius of the son of Erin has often found out a mode of putting a “comether” on the “big sarpint, the villain,” and haply closing his eyes in slumber, while he succeeded in possessing himself of the hoard which by his cunning and bravery he had so fairly won; in other words, charming the snake and possessing himself of the spoil.

Having thus glanced at the antiquity and wide spread of serpent-charming, I shall proceed to lay before you a short description of the mode in which the spell is cast over the animals by the modern jugglers of Arabia and India.

Of all the Indian serpents, next to the Cobra Minelle, the Cobra Capella, or hooded snake (Coluber Naja), called in India the “Naig,” and also “spectacle snake,” is the most venomous. It derives its names of hooded and spectacle snake from a fold of skin resembling a hood near the head, which it possesses a power of enlarging or contracting at pleasure; and in the centre of this hood are seen, when it is distended, black and white markings, bearing no distant or fanciful likeness to a pair of spectacles. The mode of charming, or, at all events, all that is to be seen or understood by the spectators, consists in the juggler playing upon a flute or fife near the hole which a snake has been seen to enter, or which his employers have otherwise reason to suppose the reptile inhabits. The serpent will presently put forth his head, a portion of his body will shortly follow, and in a few minutes he will creep forth from his retreat, and, approaching the musician, rear himself on his tail, and by moving his head and neck up and down or from side to side, keep tolerably accurate time to the tune with which his ears are ravished.

After having played for a short period, and apparently soothed the reptile into a state of dreamy unconsciousness of all that is passing, save only the harmony which delights him, the juggler will gradually bring himself within grasp of the snake, and by a sudden snatch seize him by the tail, and hold him out at arms’ length. On the cessation of the music, and on finding himself thus roughly assailed, the reptile becomes fearfully enraged, and exerts all his energies to turn upwards, and bite the arm of his aggressor. His efforts are however fruitless; while held in that position, he is utterly incapable of doing any injury; and is, after having been held thus for a few minutes before the gaze of the admiring crowd, dropped into a basket ready to receive him, and laid aside until the juggler has leisure and privacy to complete the subjugation which his wonder-working melody had begun.

When charmed serpents are exhibited dancing to the sound of music, the spectators should not crowd too closely around the seat of the juggler, for, no matter how well trained they may be, there is great danger attending the cessation of the sweet sounds; and if from any cause the flute or fife suddenly stops or is checked, it not unfrequently happens that the snake will spring upon some one of the company, and bite him. I think that it will not be amiss if I quote the description of Indian snake-charming, furnished by a gentleman in the Honourable Company’s civil service at Madras, to the writer, who vouches for its veracity:—

“One morning,” says he, “as I sat at breakfast, I heard a loud noise and shouting among my palankeen bearers. On inquiry I learned that they had seen a large hooded snake (or Cobra Capella), and were trying to kill it. I immediately went out, and saw the snake climbing up a very high green mound, whence it escaped into a hole in an old wall of an ancient fortification. The men were armed with their sticks, which they always carry in their hands, and had attempted in vain to kill the reptile, which had eluded their pursuit, and in his hole he had coiled himself up secure, while we could see his bright eyes shining. I had often desired to ascertain the truth of the report as to the effect of music upon snakes: I therefore inquired for a snake catcher. I was told there was no person of the kind in the village, but, after a little inquiry I heard there was one in a village distant three miles. I accordingly sent for him, keeping a strict watch over the snake, which never attempted to escape whilst we his enemies were in sight. About an hour elapsed, when my messenger returned, bringing the snake catcher. This man wore no covering on his head, nor any on his person, excepting a small piece of cloth round his loins: he had in his hands two baskets, one containing tame snakes, one empty: these and his musical pipe were the only things he had with him. I made the snake catcher leave his two baskets on the ground at some distance, while he ascended the mound with his pipe alone. He began to play: at the sound of the music the snake came gradually and slowly out of his hole. When he was entirely within reach, the snake catcher seized him dexterously by the tail, and held him thus at arms’ length,[Pg 235] whilst the enraged snake darted his head in all directions, but in vain: thus suspended, he has not the power to round himself so as to seize hold of his tormentor. He exhausted himself in vain exertions, when the snake catcher descended the bank, dropped him into the empty basket, and closed the lid: he then began to play, and after a short time raised the lid of the basket, when the snake darted about wildly, and attempted to escape; the lid was shut down again quickly, the music always playing. This was repeated two or three times; and in a very short interval, the lid being raised, the snake sat on his tail, opened his hood, and danced quite as quietly as the tame snakes in the other basket, nor did he again attempt to escape. This, having witnessed it with my own eyes, I can assert as a fact.”

I particularly request the attention of my readers to the foregoing account, as, from the circumstance of its having been furnished by an eye-witness, and a man whose public station and known character were sufficient to command belief in his veracity, it will prove serviceable to me by and bye, when I shall endeavour to disprove the ridiculous assertions of Abbé Dubois[2] and others, who hold that serpent-charming is a mere imposition, and assert, certainly without a shade of warranty for so doing, that the serpents are in these cases always previously tamed, and deprived of their poison bags and fangs, when they are let loose in certain situations for the purpose of being artfully caught again, and represented as wild snakes, subdued by the charms of their pipe. I shall, however, say no more at present of Dubois, Denon, or others who are sceptical on this subject, but shall leave the refutation of their fanciful opinions to another opportunity—my present purpose being the establishment of facts, ere I venture to advance a theory.

I shall therefore conclude my present paper, and in my next, besides adducing many other important facts relative to serpent-charming, shall endeavour to throw some light upon the real mode by which it is effected.

H. D. R.

If it be no part of the English constitution, it is certainly part of the constitution of Englishmen to grumble. They cannot help it, even if they tried; not that they ever do try, quite the reverse, but they could not help grumbling if they tried ever so much. A true-born Englishman is born grumbling. He grumbles at the light, because it dazzles his eyes, and he grumbles at the darkness, because it takes away the light. He grumbles when he is hungry, because he wants to eat; he grumbles when he is full, because he can eat no more. He grumbles at the winter, because it is cold; he grumbles at the summer, because it is hot; and he grumbles at spring and autumn, because they are neither hot nor cold. He grumbles at the past, because it is gone; he grumbles at the future, because it is not come; and he grumbles at the present, because it is neither the past nor the future. He grumbles at law, because it restrains him; and he grumbles at liberty, because it does not restrain others. He grumbles at all the elements—fire, water, earth, and air. He grumbles at fire, because it is so dear; at water, because it is so foul; at the earth, in all its combinations of mud, dust, bricks, and sand; and at the air, in all its conditions of hot or cold, wet or dry. All the world seems as if it were made for nothing else than to plague Englishmen, and set them a-grumbling. The Englishman must grumble at nature for its rudeness, and at art for its innovation; at what is old, because he is tired of it; and at what is new, because he is not used to it. He grumbles at everything that is to be grumbled at; and when there is nothing to grumble at, he grumbles at that. Grumbling cleaves to him in all the departments of life; when he is well, he grumbles at the cook; and when he is ill, he grumbles at the doctor and nurse. He grumbles in his amusements, and he grumbles in his devotion; at the theatres he grumbles at the players, and at church he grumbles at the parson. He cannot for the life of him enjoy a day’s pleasure without grumbling. He grumbles at his enemies, and he grumbles at his friends. He grumbles at all the animal creation, at horses when he rides on them, at dogs when he shoots with them, at birds when he misses them, at pigs when they squeak, at asses when they bray, at geese when they cackle, and at peacocks when they scream. He is always on the look-out for something to grumble at; he reads the newspapers, that he may grumble at public affairs; his eyes are always open to look for abominations; he is always pricking up his ears to detect discords, and snuffing up the air to find stinks. Can you insult an Englishman more than by telling him he has nothing to grumble at? Can you by any possibility inflict a greater injury upon him than by convincing him he has no occasion to grumble? Break his head, and he will forget it; pick his pocket, and he will forgive it, but deprive him of his privilege of grumbling, you more than kill him—you expatriate him. But the beauty of it is, you cannot inflict this injury on him; you cannot by all the logic ever invented, or by all the arguments that ever were uttered, convince an Englishman that he has nothing to grumble at; for if you were to do so, he would grumble at you so long as he lived for disturbing his old associations. Grumbling is a pleasure which we all enjoy more or less, but none, or but few, enjoy it in all the perfection and completeness of which it is capable. If we were to take a little more pains, we should find, that having no occasion to grumble, we should have cause to grumble at everything. But we grow insensible to a great many annoyances, and accustomed to a great many evils, and think nothing of them. What a tremendous noise there is in the city, of carts, coaches, drays, waggons, barrel-organs, fish-women, and all manner of abominations, of which they in the city take scarcely any notice at all! How badly are all matters in government and administration conducted! What very bad bread do the bakers make! What very bad meat do the butchers kill! In a word, what is there in the whole compass of existence that is good? What is there in human character that is as it should be? Are we not justified in grumbling at everything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth? In fact, gentle reader, is the world formed or governed half so well as you or I could form or govern it?—From a newspaper.

The very essence of vulgarity, after all, consists merely in one error—in taking manners, actions, words, opinions, on trust from others, without examining one’s own feelings, or weighing the merits of the case. It is coarseness or shallowness of taste, arising from want of individual refinement, together with the confidence and presumption inspired by example and numbers. It may be defined to be a prostitution of the mind or body to ape the more or less obvious defects of others, because by so doing we shall secure the suffrages of those we associate with. To affect a gesture, an opinion, a phrase, because it is the rage with a large number of persons, or to hold it in abhorrence because another set of persons very little, if at all, better informed, cry it down to distinguish themselves from the former, is in either case equal vulgarity and absurdity. A thing is not vulgar merely because it is common. It is common to breathe, to see, to feel, to live. Nothing is vulgar that is natural, spontaneous, unavoidable. Grossness is not vulgarity, ignorance is not vulgarity, awkwardness is not vulgarity; but all these become vulgar when they are affected and shown off on the authority of others, or to fall in with the fashion or the company we keep. Caliban is coarse enough, but surely he is not vulgar. We might as well spurn the clod under our feet, and call it vulgar. Cobbett is coarse enough, but he is not vulgar. He does not belong to the herd. Nothing real, nothing original, can be vulgar; but I should think an imitator of Cobbett a vulgar man. Simplicity is not vulgarity; but the looking to imitation or affectation of any sort for distinction is. A Cockney is a vulgar character, whose imagination cannot wander beyond the suburbs of the metropolis. An aristocrat, also, who is always thinking of the High Street, Edinburgh, is vulgar. We want a name for this last character. An opinion is often vulgar that is stewed in the rank breath of the rabble; but it is not a bit purer or more refined for having passed through the well-cleansed teeth of a whole court. The inherent vulgarity lies in the having no other feeling on any subject than the crude, blind, headlong, gregarious notion acquired by sympathy with the mixed multitude, or with a fastidious minority, who are just as insensible to the real truth, and as indifferent to every thing but their own frivolous pretensions. The upper are not wiser than the lower orders, because they resolve to differ from them. The fashionable have the advantage of the unfashionable in nothing but the fashion. The true vulgar are the persons who have a horrible dread of daring to differ from their[Pg 236] clique—the herd of pretenders to what they do not feel, and to do what is not natural to them, whether in high or low life. To belong to any class, to move in any rank or sphere of life, is not a very exclusive distinction or test of refinement. Refinement will in all classes be the exception, not the rule; and the exception may occur in one class as well as another. A king is but a man with a hereditary title. A nobleman is only one of the House of Peers. To be a knight or alderman—above all, to desire being either, is confessedly a vulgar thing. The king made Walter Scott a baronet, but not all the power of the Three Estates could make another “Author of Waverley.” Princes, heroes, are often commonplace people, and sometimes the reverse; Hamlet was not a vulgar character, neither was Don Quixote. To be an author, to be a painter, one of the many, is nothing. It is a trick, it is a trade. Nay, to be a member of the Royal Academy, or a Fellow of the Royal Society, is but a vulgar distinction. But to be a Virgil, a Milton, a Raphael, a Claude, is what falls to the lot of humanity but once. I do not think those were vulgar people, though, for any thing I know to the contrary, the First Lord of the Bedchamber may be a very vulgar man. Such are pretty much my notions with regard to vulgarity.—Hazlitt’s Table-Talk.

One evening last winter—a holiday evening too—when the western wind was sweeping on wild pinions from the grey hills of Tipperary, athwart the rich and level plains of the Queen’s County, when the blast roared down in the chimney, and the huge rain-drops pattered saucily against the four tiny panes which constituted the little kitchen window, I was sitting in the cottage of a neighbouring peasant, amid a small but happy group of village rustics, and enjoying with them that enlivening mirth and sinless delight which I have never found any where but at the fireside of an Irish peasant. The earthen floor was well scrubbed over; the “brullaws ov furnithure” were arranged with more than usual tidiness, and even the crockery on the well-scoured dresser reflected the ruddy glare of the red fire with redoubled brilliancy, and glittered and glistened as merrily as if they felt conscious of the calm and tranquillity of that happy scene. And happy indeed was that scene, and happy was that time, and happier still the hearts of the laughing rustics by whom I was on that occasion surrounded, and amongst whom I have spent the lightest and happiest hours of my existence.

It was, as I said, a wild night, but even the violence of the weather abroad gave an additional relish to the enjoyments within. The blast whistled fiercely in the bawn and in the haggard, but the huge fire blazed brightly on the hearth-stone. The rain fell in torrents; but, as one of the company chucklingly remarked, “the wrong side ov the house was out,” and I myself mentally exclaimed with Tam o’ Shanter,

Whilst, to wind up the climax of our happiness, a gossoon[Pg 237] who had been dispatched for a grey-beard full of “the native,” now returned, and in a few minutes a huge jug of half and half smoked on the table, and was circulated around the smiling and expectant ring, with an impetus of which the peasantry of Ireland will in a short time, from certain existing causes, have not even the remotest idea.

Well! such an evening as we had, I shall never forget; it would be vain to attempt a description. Those who have witnessed similar scenes require none, and to those who have not, any attempt at one would be useless. All therefore I shall say, is, that such a scene of fun and frolic and harmless waggery could not be found any where outside that ring which encircles the Emerald Isle, and even within that bright zone, nowhere but in the cabin of an Irish “scullogue.”

The songs of our sires, chanted with all that melancholy softness and pathetic sweetness for which the voices of our wild Irish girls are remarkable, the wild legend recited with that rich brogue and waggish humour peculiar alone to the Irish peasant, and the romantic and absurd fairy tale, told with all the reverential awe and caution which the solemnity of the subject required, long amused and excited the captivated auditors; but at length, more’s the pity, the vocalist could sing no more, having “a mighty great could intirely.” The story-teller was “as dry as a chip wid all he talked,” and even the sides of most of the company “war ready to split wid the rale dint of laughin’;” whilst, as if to afford us another illustration of the truth of the old proverb, “one trouble never comes alone,” even the old crone who had astonished us with the richness and extent of her fairy lore, was also knocked up, or rather knocked down, for the quantity of earthly spirits she had put in, entirely put out all memory of un-earthly spirits, and sent her disordered fancy, all confused as it was, wool-gathering to the classic regions of Their-na-noge.[3]

Well, what was to be done? It was still young in the night, and, better than that, a good “slug” still remained in the grey-beard, and as we all had contributed to procure the stock, so all declared that none should depart until the very last drop was drained. But how was the interval to be employed? The singer was hushed, the story-teller was exhausted, and vollies of wit and waggery had exploded until every one was tired; yet to remain silent was considered by all as the highest degree of discomfort. In this dilemma the man of the house scratched his pericranium, and, as acting by some sudden impulse, started up and handed me an old sooty book, “hoping that I would read a wollume for the edication of the company, until it would be time to retire.”

I agreed without hesitation, and on opening the dusty and smoke-begrimed volume found that it was “Sir Charles Coote’s Statistical Survey of the Queen’s County,” printed in Dublin by Graisberry and Campbell, and published by direction of the Dublin Society in the year 1801. Although well aware that the dry details of a work professedly and almost exclusively statistical, were little calculated to amuse or interest such an audience, yet, as the library of an Irish peasant is always unfortunately scanty, and in this instance, with the exception of a few trifling works on religious subjects, limited to the book in question, I determined to make the best I could of it, and for that purpose opened it at Sir Charles’s description of the immediate district in which we were situated, namely, the barony of Maryborough West, and town-land of Killeany. I read on thus:—“On Sir Allen Johnson’s estate stand the ruins of Killeany Castle; the walls are injudiciously built of very bad stones, though excellent quarry is contiguous. … Poor-man’s Bridge over the Nore was lately widened, and is very safe, but I cannot learn the tradition why it was so called.”

“Read that again, sir,” said a fine grey-headed, patriarchal old man who was present; “read that again,” said he emphatically. I did so.

“He cannot learn the tradition of Poor-man’s Bridge, inagh!” said the old man with a sneer; “faith, I believe not; I’d take his word for more nor that. But had he come to me when he was travelling the country making up his statisticks, I could open his eyes on that subject, and many others too.”

Some of those present laughed outright at the old man’s gravity of manner as he made this confident boast.

“You need not laugh—you may shut your potato-traps,” said the old man indignantly. “Grand as he was, with his gold and silver, his coach and horses, and servants with gold and scarlet livery, I could enlighten him more on the ancient history and traditions of our country than all the boddaghs of squireens whom he visited on his tour through the Queen’s County.”

These assertions served only to increase the storm of ridicule which was gathering around the old man’s head; and to put a stop to any bad blood which the occasion might call forth, I requested of him to tell us the tradition of “the Boccough Ruadh.”

After some wheedling and flattery he complied, and told a curious story, of which the following is the substance.

The river Nore flows through a district of the Queen’s County celebrated for fertility and romantic beauty. From its source amongst the blue hills of Slievebloom to its termination at New Ross, where its bright ripples commingle with the briny billows of the Irish sea, many excellent and even some beautiful bridges span its stream. Until the commencement of the last century, however, except in the vicinity of towns, there were but few permanent bridges across this river, and in the country districts access was gained over it chiefly by means of causeways, or, as they are termed, “foords,” constructed of stones and huge blocks of timber fixed firmly in the bed of the river, and extending in irregular succession from bank to bank. Over this pathway foot passengers crossed easily enough, but cattle and wheeled carriages were obliged to struggle through the water as well as they could; but in time of floods, and in the winter season when the waters were swollen, all communication was cut off except to pedestrians alone.

One of those “foords,” in former times, crossed the Nore at Shanahoe, a very pretty neighbourhood, about three miles northwards of the beautiful and rising town of Abbeyleix, in the Queen’s County. The river here winds its course through a silent glen, and now several snug cottages and farm-houses arise above its banks at either side. The country in this neighbourhood is remarkably beautiful. Several gentlemen’s seats are scattered along the banks of the river in this vicinity, all elegant and of modern erection, whilst swelling hills, sloping dales, gloomy groves, and ruins of church and tower and “castle grey,” ornament and diversify the scene.

On a gentle eminence on the eastern bank of the river, stood, about a hundred years ago, the cabin of a man named Neale O’Shea. At that period there was not another dwelling within a long distance of the “foord,” and many a time was Neale summoned from his midnight repose to guide the traveller in his passage over the lonely and dangerous river pathway.

One wild stormy December night, when the huge limestone rocks that formed the stepping-stones of the ford were lashed and chafed by the angry foam of the agitated river, Neale O’Shea’s wife fancied she heard, amid the fitful pausings of the wind, the cry of some mortal in distress. She immediately aroused her husband, who was stretched asleep on a large oak stool in the chimney corner, and told him to look out. Neale, ever willing to relieve a fellow-creature, arose, and, flinging his grey “trusty” over his expansive shoulders, and seizing a long iron-shod pole or wattle, the constant companion of his nightly excursions, hastened down to the river’s brink. He stood a moment at the verge of the ford, and tried to penetrate through the intense gloom, to see if he could discover a human form, but he could see nothing.

“Is there any one there?” he shouted in a stentorian voice, which rose high above the whistling of the blast, and the brawling of the angry and swift-rushing river.

A voice sounded at the other extremity of the ford, and the stout-hearted peasant, with steady step, crossed over the slippery stepping-stones.

“Who the devil are you?” roughly exclaimed Neale to a man who lay extended on the brink of the river, convenient to the entrance of the ford.

“Whoever I am,” faintly replied the stranger, “you are my good angel, and it was surely Providence who sent you this night to rescue me from a watery grave.”

“Whoever you are,” again said Neale, “come along with me, and Kathleen and the childre will make you welcome in my cabin until morning.” So saying, he seized the bending form of the wayworn stranger, and flinging him on his back with herculean strength, trudged over the stepping-stones, chuckling with delight, and gaily whistling as he went.

The dangerous pass was soon crossed, and arriving at the door, Neale pushed it before him, and with a smile deposited his trembling burthen on the warm hearth. A fine fire blazed[Pg 238] merrily, and its flickering beams fell brightly on the face of the stranger. He was a tall, portly figure, stooped as if from extreme suffering more than age, and had a wooden leg. His features, which had evidently been handsome in his youth, were worn, pale, and attenuated, and he might be about fifty years of age. His clothes were faded and ragged; he was entirely without shoes or stockings; and his head was covered by a broad-brimmed leathern hat, under which he wore an enormous red nightcap of coarse woollen cloth.

The good Kathleen now set about preparing supper, and while thus employed, the stranger gave them a brief account of his bygone life. He told them that he was a native of the north of Ireland, and that he had spent several years of his youth at sea; that being wounded in a fray with smugglers on the coast of France, and losing his leg, he was discharged from his employment, and sent adrift on the world, without having one friend on earth, or a penny in his pocket. In this exigence he had no alternative but to apply to the commiseration of his fellow-creatures, and had thus for the last twenty years wandered up and down, entirely dependent on the bounty and charity of the public.

Supper was now ready, and having partaken of a comfortable meal, the wanderer went to rest in a comfortable “shake-down,” which the good woman had prepared for him in the chimney corner. The storm died away during the night, and next morning the watery beams of the winter’s sun shone faintly yet gaily on the smooth surface of the silvery Nore.

The stranger was up at sunrise, and was preparing to depart, but his kind host and hostess would not permit him to go. They told him to stop a few days to rest himself, and in the interim, that he could not do better than take his stand at the ford, and ask alms of those who passed the way, as a great many frequented that pass; and as nothing was ever craved from them there, they would cheerfully extend their charity to an object worthy of relief.

Acting on their suggestions, the old sailor was soon sitting on a stone at the western extremity of the ford. With his old caubeen in his hand, and his head enveloped in the gigantic red nightcap, he craved alms, in the name of God and the Virgin, from all who passed the way; and before the sickly beams of the December sun had sunk behind the conical “Gizebo,” he could show more money than ever he did before, since his limb was swept off by the shot of the smuggling Frenchman.

The next morning, and every morning after, found the sailor at his post at the ford: he soon became well known to all the villagers, and from the circumstance of his always appearing with no other head-gear than the red nightcap, they nicknamed him the “Boccough Ruadh,”[4] a name by which he went ever after till his death.

Time passed on as usual, and the one-legged sailor still plied his lucrative vocation at the river pass. Neale O’Shea’s cabin still continued to afford him shelter every night, and all his days, from the crow of the cock to the vesper song of the wood-thrush, were passed at the ford, seated on that remarkable block of limestone called to this day the “Clough-na-Boccough.”[5] His hand was stretched to every stranger for alms, “for the good of their souls,” and very few passed without giving more or less to the Boccough Ruadh. Thus he acquired considerable sums of money, but constantly denied having a “keenogue;” but when bantered by any of the neighbouring urchins on the length of his purse, he would get into a great rage, and swear, by the cross of his crutch, that between buying the shough of tobacco and paying for other things he wanted, he hadn’t as much as would jingle on a tomb-stone, or what would buy a farthing candle to show light to his poor corpse at the last day. His food was of the very worst description, and unless supplied by the kind-hearted Kathleen O’Shea, he would sooner go to bed supperless than lay out one penny to buy bread. He suffered his clothes to go to rags, unless when any person in the neighbourhood would give him old clothes for charity, and he would not pay for soap to wash his shirt once in the twelvemonth. Yet no one could find out what he did with his money; he did not spend two-and-sixpence in the year, and it was people’s opinion that he was hoarding it up to give for the benefit of his soul at his dying day.

Years rolled away, and Neale O’Shea having now waxed old, died, and was gathered to his fathers in the adjacent green churchyard of Shannikill,[6] on the banks of the winding Nore. The Boccough followed the remains of his kind benefactor to his last earthly resting-place, and poured his sorrows over his grave in loud and long-continued lamentations. But though Neale was gone, Kathleen remained, and she promised that while she lived, neither son nor daughter should ever turn out the Boccough Ruadh.

It was now forty years since the Boccough first crossed the waters of the Nore, and still he was constantly to be found from morning till night on his favourite stone at the river side. In the mean time, all O’Shea’s children were married, and separated through various parts of the country, with the exception of Terry, the youngest, a fine stout fellow, now about thirty-five years of age, who still remained in a state of single blessedness, and said he would continue so, “until he would be after laying the last sod on his poor ould mother.” With gigantic strength, he inherited all his father’s kindness of heart and undaunted bravery, and he was particularly attentive to the Boccough, whom he regarded with the same affection as a child would a parent.

One morning in summer, the Boccough was observed to remain in bed longer than was his custom, and thinking that he might be unwell, Terry went to his bedside, and demanded why he was not up as usual.

“Ah, Terry, alanna,” said the old man sorrowfully, “I will never get up again until I do upon the bearer.[7] My days are spent, and I know it, for there is something over me that I cannot describe, and I won’t be alive in twenty-four hours;” and as he said these words, he heaved a deep groan, whilst Terry, wiping his eyes with the sleeve of his coat, wept bitterly.

“Will I go for the priest?” demanded Terry, sobbing as if his heart would break.

“No,” replied the old man sorrowfully, “I do not want him. It is long since I complied with my religious duties, and now I feel it is useless.”

“There is mercy still,” replied Terry; “you know the ould sayin’,

The old man replied not, but shook his head, indicating his determination to die without the consolations of religion, whilst Terry trembled for his hopeless situation.

“Well, since you won’t have the priest, will you give me some money till I bring you the doctor?” said Terry.

The old man’s eyes literally flashed fire, his form heaved with rage, and his countenance displayed demoniac indignation.

“What’s that you say?” he demanded in a ferocious tone.

Terry repeated the question.

“Send for a doctor!—give you money!” echoed the old man. “Where the devil would I get money to pay a doctor?”

“You have it, and ten times as much,” said Terry, “and you cannot deny it.”

“If I have as much money as would buy me a coffin,” said the Boccough, “may my soul never rest quiet in the grave.”

Terry crossed his brow with terror. He knew the unhappy wretch was dying with a lie on his tongue, but he resolved not to press the matter further.

“You are dying as fast as you can,” remarked Terry; “have you any thing to say before you go?”

“Nothing,” replied he faintly. “But let me be buried with my red nightcap on me.”

“Your wish must be granted,” said Terry, and he went to awake his old mother, who still lay asleep. When he returned, he found the old man breathing his last. He uttered a convulsive groan, and expired.

He was washed and stretched, and waked, with all the honours, rites, and ceremonies belonging to a genuine Irish[Pg 239] wake; and on the third day following, being the Sabbath, he was followed to the grave by crowds of the village peasantry, who remained in the churchyard until they saw his remains deposited, as they thought for ever, in the rank soil of the “City of the Dead.”

Many rumours were now current respecting the Boccough’s money. Every one but Terry believed that the “lob” fell with Terry himself. But Terry, who knew better, believed and affirmed that “what was got under the devil’s belly, always goes over his back,” and that the “old boy” had taken the spoil, and that it lay concealed in some crevice in the bank of the river.

The night following the burial of the old sailor was passed in a very disturbed and agitated manner by Terry O’Shea: he could not sleep a wink; and when he fell into a slumber, he started and moaned, and appeared frightened and annoyed.

“What ails you?” affectionately demanded his old mother, who slept in the same room, and who was kept awake by her son’s restless and disturbed manner.

“I don’t know, mother,” said Terry; “I am so frightened and tormented with dreaming of the Boccough Ruadh, that I am almost out of my natural senses. Even at this moment I think I see him walking the room before me.”

“Holy Mary, protect us!” ejaculated the old woman. “And it is no wonder that his misforthunate soul would be star-gazing about—and to die without the priest, and a curse and a lie in his mouth!”

Terry groaned agitatedly.

“And how does he appear in your dreams?” asked the old woman.

“As he always was,” replied Terry. “But I think I see him pointing to his red nightcap, and endeavouring to pull it off with his old withered hand.”

“Umph!” said the old woman, in a knowing tone. “Ha! ha! I have it now. Are you sure that the strings of his nightcap were unloosed before he was nailed up in the coffin?”

“I don’t know,” was the reply.

“I’ll go bail they weren’t,” said the old woman; “and you know, or at any rate you ought to know, that a corpse can never rest in the grave when there is a knot or a tie upon any thing belonging to its grave-dress.”

Terry emitted another deep groan.

“Well, acushla,” said the old mother, “go to-morrow, and take a neighbour with you, and open the grave, and see if any thing be asthray. If you find the nightcap or any thing else not as it should be, set it to rights, and close the grave again decently, and he will trouble you no more.”

“God send,” was Terry’s brief but emphatic response.

Early next morning Terry was at the Boccough’s grave, accompanied by a man of the neighbourhood. The coffin was opened, the corpse examined, and, according to the mother’s prediction, the red nightcap was found knotted tightly under the dead man’s chin. Terry proceeded to unloosen it, and in the act of doing so, a corner of the nightcap gave way, and out peeped a shining golden guinea.

“Ah ha!” mentally exclaimed Terry, “that’s no blind nut any how; there’s more where that was, but I had better keep a hard cheek!” So, without seeming to appear any way affected, he opened the knot, closed the coffin, shut up the grave, and departed homewards, without acquainting his comrade with what he had seen.

The moment Terry entered his own door, he told his mother about the guinea, and expressed his determination to go that very night, and fetch the red nightcap home with him, “body and bones and all,” “for,” added he, “that guinea has its comrade; and I’ll hold you a halfpenny there’s where the old dog has the ‘lob’ concealed, and that’s what made him order me to have the red cap buried with him.”

“Asthore machree,” said the mother doubtingly, “won’t you be afraid?”

“Afraid!” echoed Terry, “devil a bit—afraid indeed! and my fortune perhaps in the red nightcap.”

The mother consented, but enjoined him to tell nobody about the matter for fear of disappointment. Terry vowed implicit obedience, and retired to his usual avocations in the garden.

Well, at last the night came, and Terry set about preparing for his strange undertaking. All the arts and prayers and charms of old Kathleen were put in requisition to preserve him from danger; and about the witching hour of twelve, with his spade on his shoulder, and his dhudeen in his mouth, the bold-hearted Terry set forward all alone to the grave-yard, shaping his course by the winding banks of the glassy river, and whistling as he went—not “for want of thought,” however, for never was man’s mind more busily occupied than was Terry’s, in predisposing of the money which he expected to find in the Boccough Ruadh’s nightcap.

After a short walk, Terry arrived at the precincts of the churchyard. It was a lovely summer’s night, the full moon shining gloriously, and myriads of pretty stars blinking and twinkling in the blue expanse, but all their native lustre was drowned in the borrowed splendour of the Queen of Heaven. Terry stood a moment to reconnoitre, and, resting on his spade, looked around with an anxious gaze. He could discover nothing; all was silent as the departed beneath his feet, except the murmuring of the river’s surges in the rear, or the barking of some village cur-dog in the hazy distance. He advanced to the grave of the Boccough, and in a few minutes the ghastly moonbeams shone full on the pale grim features of the dead. He snatched the nightcap quickly from the bald head of the corpse, put it in his pocket, and, notwithstanding the awe and superhuman terror under which he laboured, he chuckled with delight as he remarked the “dead weight” of the Boccough’s head-gear. He then closed the coffin, and as he proceeded to cover it, the clay and stones fell on it with an appalling and unearthly sound. The grave now covered up, the intrepid fellow again shouldered his spade, and sought the river’s margin, and as he strode hurriedly along its banks in the direction of his home, the splash of the otter and the diving of the water-hen more than once broke the thread of his lonely musings.

Terry was soon at his mother’s side, who since his departure had been on her knees, praying for his safe return. The nightcap was ripped up, and lo! three hundred golden guineas were the reward of Terry’s churchyard adventure! Stitched carefully in every part of the huge nightcap, the gold lay secure, so as not to attract the notice of any one, or cause the least suspicion of its proximity to the old man’s pericranium.

Terry and his mother were in ecstacies. Farms were already purchased in ideality, cattle bought, houses built, and even Terry began in his mind to make preparations for his wedding with Onny Kinshellagh, a rich farmer’s daughter of the neighbourhood, for whom he had breathed many a hopeless sigh, and who, in addition to her beauty, was possessed of fifty pounds in hard gold, a couple of good yearlings, and a feather-bed as broad as the “nine acres.”

The mother and son retired to bed, as happy as the certain possession of wealth, and the almost as certain expectations of honour and distinction, could make them. After a long time spent in constructing and condemning schemes for the future, Terry fell asleep. He had not slept long, however, when he started up with a loud scream, crying out, “the Boccough! the Boccough!” “Och, weary’s on him for a Boccough!” exclaimed the mother; “is he coming for the nightcap and the goold?”

“Oh, no,” said Terry, calmly; “but I was again dreaming of him, and I was frightened.”

“What did you dream to-night?” asked the old woman.

“I was dreaming that I was going over the foord by moonlight, and that I saw the Boccough walking on the water towards me; that he stopped at a certain big stone, and began to examine under with his hands; that I came up, and asked him what he was searching for, when he looked up with a frightful phiz, and cried out in a horrible voice, ‘For my red nightcap!’”

“God Almighty never opened one door but he opened two,” exclaimed old Kathleen. “Examine under that stone to-morrow, and by all the cottoners in Cork, you’ll find another ‘lob’ of money in it.”

“Faix, maybe so,” replied Terry; “it’s no harm to say ‘Godsend,’ and that God may make a thief of you before a liar.”

“Amen, achiernah,” replied Kathleen.

Next morning at daybreak, Terry got up, and proceeded to the identical stone where he fancied that he had seen the spirit of the Boccough. He examined it closely, and after a strict search, discovered in the sand beneath the rock a leathern pouch full of money. He seized it joyfully, and on counting its contents, found it amounted to upwards of a hundred pounds, all in silver and copper coins.

“What a lucky born man you are, Terry O’Shea!” cried the overjoyed gold-finder, “and what a bright day it was for[Pg 240] your family that the Boccough Ruadh crossed over the waters of the Nore.”

“It was not a bright day at all, but a wild, gloomy, stormy night,” said the old woman, who, unperceived, had followed her son to watch the success of his expedition.

“No matter for that,” said Terry; “there never was so bright a day in your seven generations as that dark night; I am now the richest man of my name, and I would not, this mortal minute, call Lord De Vesci my uncle.”

It is easier for the reader to imagine than for the writer to describe the manner in which this joyful day was passed by the happy mother and son. Now counting and examining the gold, and again proposing plans, and considering the best purposes to which it could be applied, they passed the hours until the summer sun had long sunk behind the crimson west.

Terry was again in bed, when he started with a wild shriek. “Mother of mercy!” he frantically vociferated, “here is the Boccough Ruadh; I hear the tramp of his wooden leg on the floor.”

“Lord save us!” said the old woman in a trembling voice, “what can ail him now? Maybe it’s more money he has hid somewhere else.”

“Oh, do you hear how he rattles about! Devil a kippeen in the cabin but he will destroy,” exclaimed poor Terry. “It’s the black day to us that ever we seen himself or his dirty thrash of money; and if God saves me till morning, I’ll go back and lave every rap ov id where I got it.”

“That would be a murdher to lave so much fine money moulding in the clay, and so many in want of it; you shall do no such thing,” said the mother.

“I don’t care a straw for that,” said Terry. “I would not have the ould sinner, God rest his sowl, stravagin’ every other night about my honest decent cabin for all the goold in the Queen’s County.”

“Well, then,” says the old woman, “go to the priest in the morning, and leave him the money, and let him dispose of it as he likes for the good of the ould vagabond’s misforthunate soul.”

This plan was agreed to, and the conversation dropt. The ghost of the Boccough still rattled and clanked about the house. He never ceased stumping about, from the kitchen to the room, and from the room to the kitchen. Pots and pans, plates and pitchers, were tossed here and there; the dog was kicked, the cat was mauled, and even the raked-up fire was lashed out of the “gree-sough.” In fact, Terry declared that if the devil or Captain Rock was about the place, there couldn’t be more noise than there was that night with the Boccough’s ghost, and this continued without intermission until the bell of Abbeyleix castle clock was tolling the midnight hour.

Terry was up next morning at sunrise, and having packed up the money which was the cause of all his trouble in his mother’s check apron, proceeded with a heavy heart to the residence of the priest, about two miles from the present Poor-man’s Bridge. The priest was not up when Terry arrived, but being well known to the domestics, he was admitted to his bed-chamber.

“You have started early,” said the priest; “what troubles you now, Terry?”

Terry gave a full and true account of his troubles, and concluded by telling him that he brought him the money to dispose of it as he thought best.

“I won’t have any thing to do with it,” said the Father. “It is not mine, so you may take it back again the same road.”

“Not a rap of it will ever go my road again,” said Terry. “Can’t you give it for his unfortunate ould sowl?”

“I’ll have no hand in it,” said the priest.

“Nor I either,” said Terry. “I wouldn’t have the ould miser polthogueing about my quiet floor another night for the king’s ransom.”

“Well, take it to your landlord; he is a magistrate, and he will have it put to some public works connected with the county,” said the priest.

“Bad luck to the lord or lady I’ll ever take it to,” said Terry, making a spring, and bounding down the stairs, leaving the money, apron and all, on the floor at the priest’s bedside.

“Come back, come back!” shouted the Father in a towering passion.

“Good morning to your ravirince,” said Terry, as he flew with the swiftness of a mountain deer over the common before the priest’s door. “Ay, go back, indeed; catch ould birds with chaff. You have the money now, and you may make a bog or a dog of it, whichever you plaise.”

In an hour after, the priest’s servant man was on the road to Maryborough, mounted on the priest’s own black gelding, with a sealed parcel containing the Boccough’s money strapped in a portmanteau behind him, and a letter to the treasurer of the Queen’s County grand jury, detailing the curious circumstances by which it came into his possession, and recommending him to convert it to whatever purpose the gentlemen of the county should deem most expedient.

The summer assizes came on in a few days, and the matter was brought before the grand jury, who agreed to expend the money in constructing a stone bridge over the ford where it was collected.

Before that day twelvemonth, the ford had disappeared, and a noble bridge of seven arches spanned the sparkling waters of the Nore, which is here pretty broad and of considerable depth. From that day to this it is called the “Poor-man’s Bridge,” and I never cross it without thinking of the strange circumstances which led to its erection.

The spirit of the Boccough Ruadh never troubled Terry O’Shea after, but often, as people say, amid the gloom of a winter’s night, or the grey haze of a summer’s evening, may the figure of a wan and decrepid old man with his head enveloped in a red nightcap, be seen wandering about Poor-man’s Bridge, or walking quite “natural” over the glassy waters of the transparent Nore.

[3] That imaginary region under ground, supposed by the peasantry to be the residence of spirits and fairies.

[4] The red beggarman.

[5] Anglice, the Stone of the Cripple, or the stone of the beggarman. This stone lay for many years in the position it occupied in the days of the “Boccough,” but is now incorporated in the stonework of the parapet of the bridge. It was believed to be enchanted, and the peasantry of the neighbourhood used to affirm that it descended to the river to drink, every night at the hour of twelve o’clock. This belief is now almost exploded, but however it is affirmed to be the identical stone on which the Boccough collected his wealth.

[6] This is a very ancient churchyard, situated on a gentle eminence overhanging the western bank of the river Nore, and about half a mile from Poor-man’s Bridge. The ruins of a church or monastic establishment still remain in the centre of the grave-yard. It is said to have been erected by St Comgall, from whom it took the name of Cell-Comgall, though now called Shankill, or Shannakill. St Comgall was born in Ulster in 516, and was educated under St Fintan, in the monastery of Clonenagh, near Mountrath, in the Queen’s County. He died on the 10th of May 601.

[7] The bier or hand-carriage on which the dead are borne to the grave.

An Excuse.—Miravaux was one day accosted by a sturdy beggar, who asked alms of him. “How is this,” inquired Miravaux, “that a lusty fellow like you is unemployed?” “Ah!” replied the beggar, looking very piteously at him, “if you did but know how lazy I am!” The reply was so ludicrous and unexpected, that Miravaux gave the varlet a piece of silver.

An Incident.—At the time Commodore Elliot commanded the navy at Norfolk (I think it was), happening to be conducting a number of ladies and gentlemen who were visiting the yard, he chanced to see a little boy who had a basket full of chips, which he had gathered in the yard; probably to show his importance he saluted him, and asked where he got the chips. “In the yard,” replied the boy. “Then drop them,” said the brave man. The little boy dropped the chips as he was ordered, and after gaining a safe distance, turning round with his thumb to his nose, said, “That is the first prize you ever took, any how!”

Solon enacted, that children who did not maintain their parents in old age, when in want, should be branded with infamy, and lose the privilege of citizens; he, however, excepted from the rule those children whom their parents had taught no trade, nor provided with other means of procuring a livelihood. It was a proverb of the Jews, that he who did not bring up his son to a trade, brought him up as a thief.

If there be a lot on earth worthy of envy, it is that of a man, good and tender-hearted, who beholds his own creation in the happiness of all those who surround him. Let him who would be happy strive to encircle himself with happy beings. Let the happiness of his family be the incessant object of his thoughts. Let him divine the sorrows and anticipate the wishes of his friends.

A cheerful heart paints the world as it finds it, like a sunny landscape; the morbid mind depicts it like a sterile wilderness, palled with thick vapours, and dark as “the shadow of death.” It is the mirror, in short, on which it is caught, which lends to the face of nature the aspect of its own turbulence or tranquillity.

The lazy, the dissipated, and the fearful, should patiently see the active and the bold pass by them in the course. They must bring down their pretensions to the level of their talents. Those who have not energy to work must learn to be humble.—Sharp’s Essays.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; J. Drake, Birmingham; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.