| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/wongowiseoldcrow00moon |

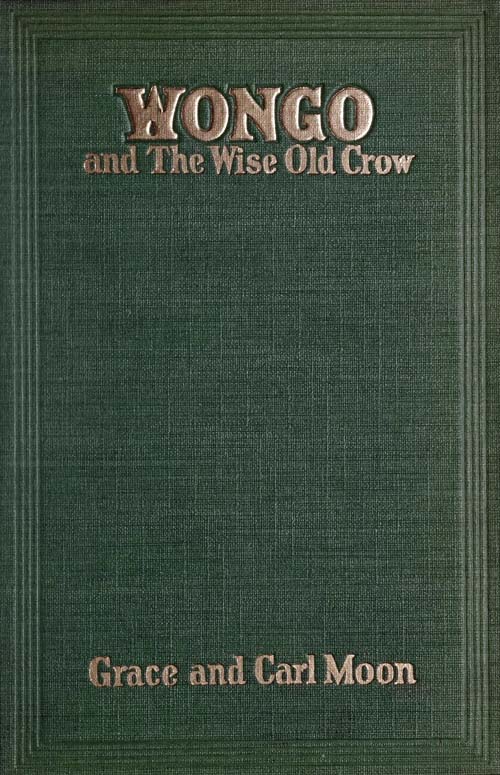

Wongo, the little brown bear, Cho-gay, the Indian boy-ruler, and

Kaw, the wise old crow.

WONGO

and

The Wise Old Crow

by

GRACE AND CARL MOON

ILLUSTRATIONS BY CARL MOON

The

Reilly & Lee Co.

CHICAGO

Printed in the United States of America

Copyright, 1923

by

The Reilly & Lee Co.

All Rights Reserved

Wongo and the Wise Old Crow

| A Daring Plot | |

| Chapter | Page |

| 1—In Timbertangle | 13 |

| 2—Wongo and Kaw Make a Plan | 32 |

| 3—Wongo Has a Wild Night | 46 |

| 4—The Sad Tale of Old Grouch | 60 |

| Cho-gay of Timbertangle | |

| Chapter | |

| 1—An Indian Boy Ruler | 69 |

| 2—The Fox and the Wolf | 87 |

| 3—Sandy Tells a Tale | 108 |

| 4—Kil-fang Startles Timbertangle | 121 |

| 5—The Rout of the Wolf Pack | 129 |

| The Thunder Drum | |

| Chapter | |

| 1—The Year of the Great Thirst | 133 |

| 2—Grayhead, the Grizzly | 144 |

| 3—At the Cave of Cho-gay | 153 |

| 4—In the Up-Above Country | 166 |

| 5—Rain Comes to Timbertangle | 176 |

To our most flattering listeners

Francis and Mary Caryl

this book is lovingly dedicated

Grace and Carl Moon

A SUDDEN gust of cold wind swept along the mountain side and rattled the dry leaves and dead branches of some jack-oak bushes that stood at the entrance of a snug little cave. Its sole occupant, awakened by the noise, opened his eyes and looked blinkingly up at the pale dawn-light that shone on the familiar rocks of the roof above him. Once awake, he realized that he was thirsty and hungry, but he hated to get up, it would be so nice to have just a little more sleep.

[14]While the cave-dweller was deciding between the call of his stomach and his desire to sleep, a big bluejay, with feathers rumpled by the wind, lit on a rock at the cave entrance and, after peering within, called out:

“Sleepy-head! Sleepy-head!” Then, as there was no response from the cave, he called again: “Get up, Wongo. ‘The early bird catches the worm,’ and the early bear may catch the fat sheep.”

“That’s all right about the early bird and the worm,” growled the little bear angrily, “but a bird doesn’t know much and it served the silly worm right for getting up too early. He ought to get caught.”

Then Wongo got to his feet and, as the noisy bluejay flew away, he crawled sleepily out of the cave and ambled down a secret trail that led to the canyon below.

Although the sun was not quite up on this eventful day, a pale dawn-light flooded the mountain side, causing the trees and bushes to look dim and ghostly.

Wongo was in an ill temper. Hunger, thirst, and the desire to sleep, to say nothing of the wind that was bent on blowing his fur the wrong way, made him growl under his breath. And now he must go to the little stream that ran through the dark[15] canyon far below and get a drink, and if he met any kind of an animal on the way that was good to eat—well, that animal had better look out for himself!

Suddenly he stopped and sniffed the cool breeze that was now sweeping up from the gorge below.

“Meat!” he ejaculated. “Fresh meat of the young calf.” Then quickening his pace he soon stood on the rim of the canyon, with his nose in the air, sniffing to the right and to the left. It took but a moment to decide that the good smell came from up the canyon, but up the canyon was forbidden ground. That tantalizing odor meant just one thing, and that was that old Grouch, the meanest and most feared old bear in all Timbertangle, had killed a calf, and had, no doubt, enjoyed a hearty breakfast.

Wongo had never seen old Grouch, but he had always been very curious to know what he looked like. The fearsome tales told of the old bear by the many animals who had seen him had caused the little bear to leave the upper end of the canyon strictly alone. But on this particular morning hunger and curiosity weighed heavily against his fear. What if the old rascal had eaten all he wanted of the meat, and had gone away for a drink, or an early morning stroll, leaving a part of[16] it in his den? Couldn’t Wongo creep up close enough to the den to see without any danger to himself? Suppose old Grouch was as bad as everyone said he was, couldn’t Wongo run as fast as any old bear?

As he argued thus to himself he stood gazing below him where, in the dim light of the dawn, he could see familiar patches of haw and berry bushes that still had plenty of fruit on them, but he was tired of haws and berries. The keen October air sharpened his appetite, and he wanted something more solid and satisfying than berries or the grubs that would be found under the flat rocks when the sun came up.

Again Wongo took long sniffs of the air, and while caution told him to give old Grouch a wide berth, appetite and curiosity got the upper hand and he moved softly up the canyon toward the forbidden ground. More and more tempting grew the smell of the fresh meat, as he neared what his nose now told him must be old Grouch’s den. He stopped beside a thicket of jack-oaks and, as the smell seemed to come from just beyond it, he slowly and carefully put his head through them that he might see.

Suddenly there was a rush from behind, followed by a stinging blow on the head that sent[17] him tumbling over and over down the hillside. Scrambling to his feet he made off at top speed, catching a glimpse of the great black bear from over his shoulder as he ran.

“I’ll teach you to go snooping around my cave, you little fat thief,” shouted old Grouch, as he glared after the fleeing Wongo.

In mingled fear and rage the young bear ran on as fast as he could, not stopping until he arrived at the little brook at the bottom of the canyon. Here he took a long drink, and while it cooled his temper somewhat, the cold water fairly splashed in his empty stomach.

As the thought of the fresh meat still lingered in his mind, Wongo wondered if there might not be a stray sheep or two down on the plains near the canyon’s mouth. Slowly returning to the rim of the gorge, he started disgustedly along a little trail that led toward the haw and berry bushes. But his thoughts were not of haws and berries. In the fall there was often the possibility of stealing a sheep, as the Navaho Indian women drove their flocks well up into the canyon for water at this season of the year. The thick underbrush caused the sheep to scatter in their passage up the canyon bed, thus giving any brave and cunning young bear a fine chance to make off with a nice meal of[18] fresh mutton, provided his bravery and cunning were sufficient to outwit the Navaho dogs.

Twice, of late, he had stolen a nice fat sheep from the scattered flocks, but on both occasions he had been assisted by his friend Kaw, the crow. Kaw had signaled to him from the top of a tall pine tree, where the sharp-eyed old bird could watch the movements of the dogs and could tell him where they were at any moment. As for the Indian women and boys who drove the sheep, he could watch them himself as they were tall enough to be seen above the underbrush, and he had no difficulty in keeping out of their sight.

A queer kind of an old bird was Kaw, but a good friend, as many an occasion had proven. The old crow loved to tease the little bear, and Wongo always pretended to be indifferent to the teasing, yet he secretly liked Kaw best when he was in a teasing mood, as on such occasions he frequently talked in rhyme, or recited some verses that amused Wongo very much.

His first meeting with Kaw had been a strange one, and he remembered quite clearly all that had taken place on that occasion. That was more than a year ago now, when Wongo, who at that time was scarcely more than a fat cub, was on his way home one evening. He had been ambling along[19] through the quiet forest, and had chanced to pass the tall stump of a hollow tree that had a great black hole near the bottom of it. Having been born with a great desire to inquire into all things, he suddenly wished to know just what it was like inside of that hole. He therefore walked up to the stump, and had just put his little nose inside when he heard the most fearful squawking and croaking noise that seemed to come from high up in the stump itself.

“Woof!” ejaculated Wongo, as he jumped backward, his little eyes bulging with fright and the short hair on his back standing up like porcupine quills. Stumbling backward for a dozen paces he sat down upon his haunches and gazed wide-eyed up at the top of the stump. There sat a crow who was laughing so hard his black wings were fluttering against his sides. It was quite evident that it was he who had made the unearthly noise, and that he had simply shouted it down through the hollow stump.

[20]With growing anger and amazement Wongo cried out, “You black old croaker, I suppose you think you’re smart.”

At that the crow half fell, half flopped down to the top of a near-by bush, and having straightened his face into a more serious expression said:

“Don’t add a hasty temper to your weakness of indulging in idle curiosity. I could not resist so rare a bit of fun, and besides,” he added, “I taught you a valuable lesson if you will only heed it, my young friend.”

“Young, indeed!” snapped Wongo, who was at[21] that time very sensitive about his age. “Anyone can see that I am many times bigger than you, so must be much older.”

“Your size has nothing to do with your age,” replied the crow. “Listen while I tell you about the Pebble and the Sage:

Seeing from the rather blank expression on Wongo’s face that he had failed to understand the reference to Noah and the Ark, the crow continued more bluntly:

“I knew old Silvertip, your father, long before you were born, and,” he added thoughtfully, “I suppose you come by your desire to peep and pry[22] honestly enough, as it was your father’s weakness before you. Had he been less inquisitive, and had he taken my advice, he would not have been caught in the clumsy trap that proved his undoing.”

The fact that this old crow had known his father caused Wongo’s attitude toward him to change from one of anger to one of respect. He began to listen to the crow’s remarks with a more kindly feeling.

“But to go back to the lesson I tried to teach you,” continued Kaw, “you should never poke your head inside a hollow tree. If a bobcat or a swarm of bees had been in that hole they could have given you a lot of painful punishment before you could have said scat, and yet, when I come to think of it,” he added with a droll expression on his face, “I suppose you could make bees stand for you.”

“How could I?” asked Wongo. “I don’t think I understand how I could make bees do anything except get after me.”

“Well,” said the crow, as he spread his wings for flight, “if I remember my alphabet lessons rightly, a B always stands for bear.”

“That’s so,” thought Wongo as he watched Kaw wing his slow flight into the darkening forest, and he turned homeward resolved that as soon as[23] he arrived he would ask his mother to tell him about Noah and the Ark.

But all this had happened the year before, and since that time the crow had proven to be a delightful friend and companion. And now, on this cool October morning, the little bear wished that his friend Kaw would happen along to tell him if he had seen any stray sheep wandering unguarded in the canyon below.

At the thought of the recent encounter with old Grouch, his hair bristled with anger, and as he walked down the little trail hungry and disgruntled, he mumbled half aloud, “When I am grown I’ll whip old Grouch, and I’ll certainly give him such a good beating he will be glad to leave the country.”

Suddenly a familiar voice, that seemed to come from above him, remarked, “He who wins a fight does not always depend upon size, friend Wongo.”

“Hullo, Kaw,” said the bear, whose ill temper began to leave him the instant he heard the voice of his friend. “I was just thinking of you a moment ago, and when you spoke I was wishing I were big enough to whip old Grouch, and I’ll surely do it when I am grown. I had a fight with the old black rascal a few minutes ago, but it wasn’t a fair fight, for he hit me from behind, and I fell down a hill, and when I got up he was too far[24] away for me to fight him. But I’ll get even with him some day.”

“So you would grow more before attempting to punish the old enemy of the canyon, would you?” asked the crow. Then, without waiting for Wongo to reply, he asked, “Did you ever hear the story about the Terrible Turk?”

“No, I haven’t,” said the bear. “What about him?”

Clearing his throat, which at best was a bit husky, the crow began:

“Do you advise me to try to whip old Grouch now?” asked Wongo.

“Well, not in an actual fight with tooth and claw,” drawled the crow. “We sometimes have to fight with our wits, and there is usually more than one way to defeat an enemy. I, myself, have long wanted to get rid of that old trouble-maker, and we may hit upon a plan, but hush!” he ejaculated in a lower tone, “there he goes now.”

“Where?” asked Wongo, excitedly.

“Down the other side of the canyon,” replied Kaw, “but you are not high enough up to see him. I saw the old thief steal a young calf last night, and I suppose he has eaten his fill, and is now after a drink.”

“Yes,” said Wongo. “I know about that calf meat, and—” He stopped suddenly, as he thought it might be best not to tell his friend why it was that he had gotten into trouble with old Grouch.

“You are not hungry, are you, friend Wongo?”[26] asked Kaw, paying no heed to the little bear’s sudden stop in his remark about the calf meat.

“My hunger is all there is in me,” said Wongo, promptly. “I am more than half starved.”

“Well,” chuckled Kaw, “I was thinking that you might take a short cut to old Grouch’s den right now, while I keep an eye on him. I think you may find a pretty good feed beneath the big flat rock that is near the front of his cave. Keep an ear open for my call. I will let you know when he turns homeward.”

At the thought of his recent encounter with old Grouch, Wongo hesitated for a moment, but he had great faith in Kaw, and he must have something to eat, so he trotted away up the canyon as noiselessly as he could go. A half hour later, just as he had finished the last bit of Grouch’s hidden meat, he heard Kaw’s faint, far-away “caw, caw” of warning and beat a hasty retreat around the mountain side.

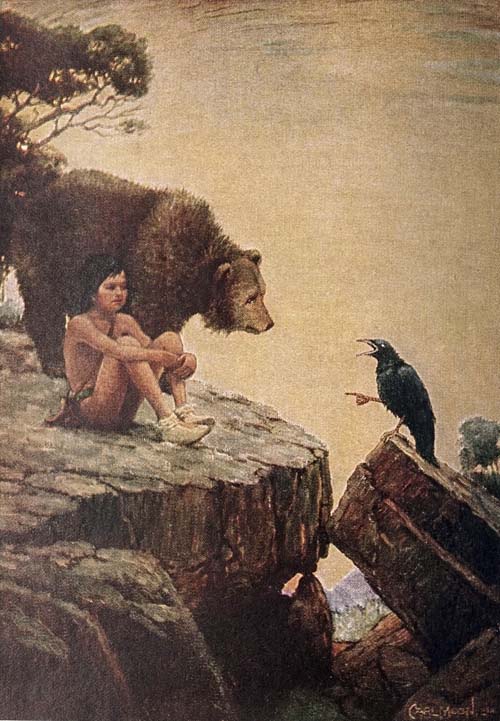

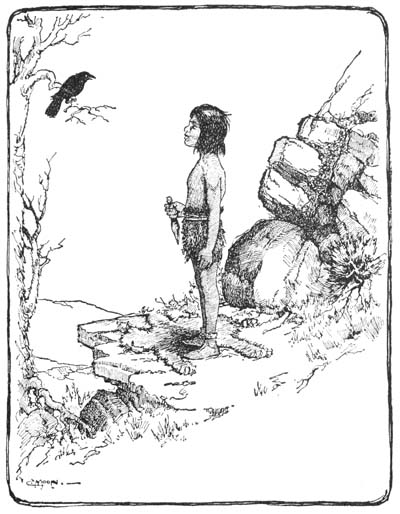

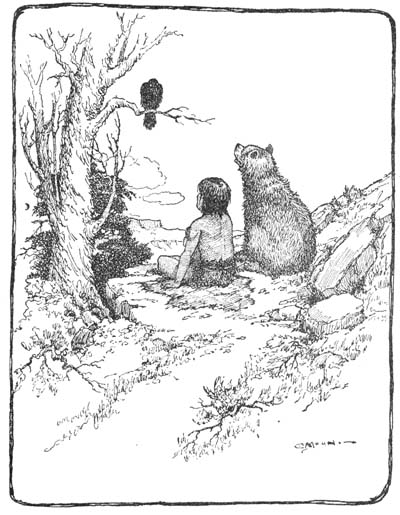

After putting a safe distance between himself and the den of old Grouch, Wongo trotted down a slope to a ledge of flat rocks that projected high above a steep cut in the mountain.

From this ledge Wongo looked down over the plains below

[28]From this ledge he had often looked down over the sage-covered plains far below, and one spot in particular had always attracted his attention and aroused his ever-present curiosity. It was a tiny place, or so it seemed from the mountain, a place where Navaho Indians lived, and Kaw had told him that it was made of mud-covered trees that were stood up together to make a kind of cave,[29] but, of course, it could not be a real cave, for real caves must be made in rocks or dug into the earth. Often, as he looked down at this strange little house, a thin, bluish cloud arose from the center of it, and when the wind was in the right direction it brought to his nostrils odors of strange things—things good to eat.

The Indian man-house always filled Wongo with wonder, and he desired more than anything else to go up to it and see just what it looked like close at hand. Once, when he had looked down upon it just at nightfall, he had seen something that shone red like a bit of the sun when it sinks in a summer haze. That shining red light was another very curious thing that he must know about, and he must see it up close. He would ask Kaw about that bit of the sun that he had seen shining from the Indian man-house.

Now that his stomach was filled, Wongo seemed to be filled with confidence also. The warm sun shone hot from the desert, its welcome rays adding to his feeling of comfort and self-assurance. Why[30] should he have fear of the little place where lived the Navahos? Why fear anything? To-night he would go down the mountain and visit the Indian man-house and see for himself just what it looked like. Nothing, aside from the dogs that he could outwit or run away from, could harm him.

He knew that the Navahos would not so much as touch him. Had not his mother told him that they believed there was a witch—whatever that was—in every bear, and that if they harmed the bear the witch thing would make great trouble come upon them? Neither his mother nor Kaw, the crow, seemed to know what a witch was, but that didn’t matter so long as it caused the Indians to have fear, and thus kept them from shooting their arrows into bears, as he had seen them shoot into deer and rabbits. Wongo had observed that when Indian arrows stuck into animals they nearly always killed them.

Turning away from the ledge, he started slowly down the mountain, deciding that he would, that very night, satisfy his curiosity about the man-house. In the meantime he would go down into the canyon and get a cool drink, after which he would visit some berry patches just over the ridge, and explore among the foothills a bit before his nap-time, which always came just after the sun[31] had walked past the middle of the sky. At that period of the day the sun’s warm rays seemed to cast a sleepy spell over the silent mountain side, so all of the animals, with one accord, had decided it should be the hour for their mid-day sleep.

So Wongo ambled down the mountain and feasted on the berries in the patch over the ridge, after a cooling drink at the canyon spring. Then the little bear went happily to his cave for his nap.

NAP-TIME had come and gone, the long, warm afternoon hours had slipped away and the sun was just wrapping itself up in a bed of pink and gold clouds that hung on the horizon, when Wongo started, somewhat cautiously, down the trail that led from the mountain through the foothills far below, and on to the open plains. As he was shuffling along, thinking how best to approach the man-house, and wondering if it would be dark enough by the time he reached the sage-covered plains to go into the open without being seen, he heard the slow flapping of wings near by and a voice that sang in Kaw’s most teasing manner:

“He waddles along with his toes turned in”

As Wongo walked on in silence, not even deigning to glance in Kaw’s direction, the latter continued still more teasingly:

“That’s enough of your poor rhyming wit,” said Wongo, sitting down beside the trail. “That last string of words is too personal, and besides, your remarks about the rug make me nervous.”

“Oh! Ho! Little bear, you must be on a nervous errand to-night, eh? By-the-by, I see that you are not headed toward home, and it nears the hour when all honest folk should be on their roosts.”

“Roosts!” ejaculated Wongo, with a disgusted grunt. “Do you think everybody roosts simply[36] because you have to? A fox or a wolf or a bear would look well roosting out on the limb of a tree, now wouldn’t they?” he asked crossly.

“That has no bearing whatever on what I said,” replied Kaw, “since I remarked that it was about time that all honest folk were on their roosts. It is well that some of us can roost, and roost high, too, when certain night-prowlers are into mischief.”

Ignoring Kaw’s teasing, Wongo suddenly asked, “What is the little red light that shines from the Indian man-house when it is dark at night? It’s like a bit of the sun when it sinks red in the summer haze.”

“That is what they call fire,” replied Kaw, “and when they make it a little blue cloud comes up out of it, and they call the cloud smoke.”

“Well, I want to see it up close,” said Wongo.

“So that’s where Mr. Curiosity is going to-night, is it?”

“How about your own curiosity?” asked Wongo. “It seems to me you have done a lot of prying yourself to have learned so much about fire and witch, and the Indian man-house.”

“Well,” said Kaw, with a chuckle, “I have to investigate a lot of things simply that I may be able to answer the foolish questions of some of my ignorant friends. I was down there on a visit[37] to the man-house myself to-day,” he added, without giving Wongo time to say anything further about his curiosity, “and there is a squaw-man at the hogan.”

“What is a squaw-man?” asked Wongo, forgetting Kaw’s remarks about foolish questions.

“Well, he’s a white-skinned man who has an Indian wife. An Indian woman is called a squaw, so the man is called a squaw-man. No men that have white skins believe in bear witches, and they like to kill bears, and they kill things with a long stick that shines, and it spits smoke with a loud noise, and it shoots a small heavy thing straight at the animal or bird that it points at. They call the bright stick a gun, and it is surely more to be feared than bows and arrows. You may see an[38] arrow coming but you can’t see the little thing that the gun stick sends out.”

“Whee!” exclaimed Wongo, his little eyes growing wide with mingled interest and fear.

“Yes,” continued the old crow, “I’ve seen this squaw-man before. Met him some years ago away over on the other side of the two ranges, and he certainly can shoot straight with that gun thing, as the loss of one of my best tail feathers bears witness—and I was flying some at the time, too. I didn’t get but a few grains of his old corn. But no matter about that now,” he said, coming back to the subject in hand, “for I must tell you more about what I saw to-day. This squaw-man came to the Indian man-house yesterday with horses tied to a big thing that moves over the ground without walking.”

“Snake?” asked Wongo.

“No!” snapped Kaw. “Don’t interrupt me with silly questions. The thing has four round things beneath, where its legs ought to be, and they roll over and over when the horses walk. The man calls it by the name of ‘wagon.’ On top of it is a thing he calls a cage. It has four sides and each side is like a row of little trees that have grown very close together, only you couldn’t get through the little trees on the cage thing, as they[39] are fastened into a floor place and into a strong top that is called a roof. I heard him explain it all to the Indians.”

“What is it for?” asked Wongo.

“Well, the squaw-man told the Indian men that something, or somebody called a ‘show’ wants him to catch a bear, and not kill it, but put it inside of the cage thing. Then the Indian men laughed and some looked afraid. When the squaw-man gets a bear into the cage I suppose the horses will walk with it and roll it off to the place where ‘show’ is. Now the reason I tell you all this, when I ought to be at home and asleep, is because I have a plan that you and I must carry out to-night.”

“I guess it’s so late I’ll not visit the man-house,” said Wongo, as he slowly turned around on the trail and headed toward home.

“Tut-tut!” said the crow. “You will have to be much braver than that if you expect ever to punish old Grouch.”

“Who said anything about being afraid?” asked Wongo, pulling himself up short and trying to look very brave.

“I beg your pardon,” said Kaw, gravely. “I was foolish enough to think, for the moment, that you might possibly be going home because you[40] feared the squaw-man, but now that I see by your look that you could never be a coward I know that you will be glad to accompany me down to the man-house.”

“Do you mean to say that you are going back to the Indian den to-night?” asked Wongo, trying to conceal his fear.

“That is a part of my plan, and we will go together. Listen. Since seeing the squaw-man with his cage thing, I have thought of a scheme, and if we carry it out successfully we will be doing ourselves and everybody in Timbertangle a great service. If you will follow my instructions no harm can come to you.”

“Let me hear the plan,” said Wongo, sitting down again somewhat nervously.

“On the west side of the man-house is a corral,” began Kaw. “There are sheep and goats in the corral to-night. The door of the man-house is toward the east. All Navaho Indians make their hogans with the door toward the rising sun. The horses are hobbled in a bunch on the south side of the hogan. The wind is from the south. We will go up to the man-house from the north, so that the dogs and horses will not smell you coming. There would certainly be trouble if they did,” he added.

[41]“The moon will not be up to take its night walk for some time yet, but let us be on our way, as we can talk as we go. You are to go to the top of the little hill that you will find close to the man-house, and when you are there wait until you hear me call. Be careful to travel as noiselessly as ever you did in your life. Three of my crow friends will be with me in the sagebrush on the opposite side of the man-house. When I see you come to the top of the little hill my friends and I will make a loud and strange noise that will set all the dogs in our direction, and will, if all goes well, stampede the horses.”

“Why do you scare the horses?” asked Wongo.

“Well,” replied Kaw, “four of the horses belong to the squaw-man, and I just want to make him pay up a bit for the loss of my tail feather.”

“Ho, ho!” growled Wongo, “I understand that part of your strange plan at least. Go on.”

“As soon as you hear us,” continued Kaw, “and know that the dogs have run in our direction, you make a jump for the corral and grab a sheep. Don’t make a mistake and get a goat, for there are big ones in that flock that the Indians keep to protect the sheep from the coyotes, and if you should get one of them you might come to grief. Don’t kill the sheep, but make off with it as fast as you[42] can travel, taking the shortest cut to the canyon. Hold the sheep around the neck so that it can’t make any noise.

“Make as plain a trail with your feet as you can, by running on soft ground whenever you find any. Go straight up the canyon toward old Grouch’s den. You’ll be safe enough even though he hears you and comes out to fight, as all you will have to do is to kill the sheep, drop it and run. He will stop quickly enough when he finds the meat, but I hope he will not hear you, and the chances are that he won’t, as he has had a big feed to-day and will sleep. However, he is an old glutton and, thanks to your making way with the remainder of his calf meat this morning, he will be keen enough for another square meal before daylight comes.

“When you’ve carried the sheep up to the thicket that is near his den, kill it and lay it down. Then walk backwards, backwards mind you, to the big vine-covered rock, and when you come to it jump straight over it, and run to your home by the long way round the mountain.”

“What’s all this for?” asked Wongo, who was confused by the long and seemingly foolish instructions. “It sounds like a lot of nonsense to me,” he continued. “Why in the world should I risk my neck to get a sheep for old Grouch?”

[43]“I am just coming to the explanation,” said Kaw. “When the squaw-man and the Indians start out early to-morrow morning to catch a live bear, what do you suppose they will do?”

“They will find my trail and follow it,” said Wongo promptly, “and it will be a sorry day for me if they catch me.”

“Well,” replied Kaw, “you are right and you are wrong. They will follow your trail, but it will be old Grouch and not you that they will catch. The old rascal will probably smell the fresh mutton as soon as you drop it, and when he comes down for it his tracks will meet yours, and will be more fresh than yours when the squaw-man’s dogs come to that part of the trail.”

“Ho, ho! I see your scheme now,” said Wongo, chuckling at the thought of old Grouch being captured by the terrible squaw-man. “But,” said he, stopping suddenly as the fearful thought struck him, “what if the dogs should get off onto my trail when they reach the big rock?”

“I have provided for just that possibility,” said Kaw. “I have engaged an old friend of mine to pick up your trail as soon as you leave the rock and,” he continued with a chuckle, “they won’t follow him very far.”

“Who is he?” inquired Wongo.

[44]“Well,” said Kaw, whose voice seemed just a shade apologetic, “he is a polecat for whom I have done a good turn, and he is both anxious to serve me and to get even with old Grouch, who destroyed the polecat’s nest when in one of his mad fits.”

“I hope he stays some distance behind me,” said Wongo thoughtfully.

“After leaving the sheep,” said Kaw, continuing his instructions, “go on around the mountain and I will meet you at the flat-topped rock near your cave. We will then compare notes, and then go out to warn every bear, and all of our animal friends on the mountain side, to leave the country before sun-up—all except Grouch,” he added with a grin.

The two had now come to the sage-covered flat that lay near the Indian hogan, so quickly repeating the most important part of his instructions, and giving Wongo a final warning to use the utmost care, Kaw flew away to the south. Although it was dark, Wongo could see the outline of the man-house some little distance away. He walked toward it very cautiously, noticing that it appeared much larger than it had seemed to be when viewed from the mountain side. Reaching the top of the little hill that the crow had described, he settled[45] down in the sagebrush where he could look about him without fear of making a noise. He was now only a few yards from the hogan, and through a little hole in the side came the mysterious red light, while from the top of the house drifted a thin little cloud that looked white and ghostly in the darkness. Strong were the odors it brought, odors of unfamiliar things mingled with the smell of meat. Lost in wonder about all of these strange things, Wongo almost jumped out of his skin when a black object swooped down and alighted at his side.

“Don’t be so nervous!” commanded Kaw. “The dogs are all on the other side. I came over to tell you that you will have time to go up to that hole, through which the firelight is showing, and have a look inside the man-house, if you will go with care. Keep your wits about you and your ears open. I will start the big noise in a very short time,” he added as he flew noiselessly away.

LEFT alone, with the Navaho dogs and the Indian man-house so near at hand, Wongo hesitated for a moment before deciding to go up to the hole in the mysterious house, but this mighty appeal to his curiosity overpowered his fears, and he started toward the spot of light.

Wongo put his eye to the hole

[48]His heart beating wildly with excitement, he reached the little hole in the wall of the hogan and cautiously put his eye to it. What a sight met his startled gaze! There were several Navaho men in the house, and two or three little men—Kaw had called them boys. The first thing that caught Wongo’s wondering attention was the fire. There it was, right in the center of the man-house. It was alive, and was eating sticks and bits of bark that popped and cracked as they died! And as it ate it seemed to leave a white dust that danced up into the light, when the men prodded the fire with a stick. Heat seemed to come from it, like the heat from the sun. Wongo had never seen anything like it before. On the floor around[49] the fire sat the Indians and the voice of one of the boy-men drew Wongo’s attention away from the fire. One old man was making something with straight sticks and the boy-man asked, “Why must the feathers be put on the end of the arrows, father?”

“It is the tail feathers of the bird that makes the bird fly straight, and it is the feathers of the arrow’s tail that makes it go straight when it leaves the bow string,” replied the old man.

“Why do you make long little grooves on the sides of the arrow, father?” asked the boy-man.

“When the arrow goes into the deer the grooves let the blood come out at the sides. If no grooves are there, the arrow fills the wound, and the deer may run far and get away before he is dead.”

Wongo drank in this information and put it into the back of his thoughts for future use. Then his eye wandered around the circle of men, some holding long sticks in their lips, from which came little blue clouds like the larger clouds from the fire. This was confusing, and he could not understand it. Then his gaze fell suddenly on a man unlike any he had ever seen before. He sat back on the farther side of the fire against the wall of the man-house. His skin was white, and the lower part of his face had long hair on it, like the hair[50] on the throat of the timber wolf in winter, only the man-hair was black.

Just back of the man with the white skin was a long, shining stick, standing against the wall. Suddenly the thought came to Wongo that the white-skinned man was the “squaw-man” and the shining stick of strange shape was the gun thing that could shoot to kill a bear. A little shiver of fear crept over him, when the silence was broken again by the boy-man, who asked, “Would the arrow from a strong bow kill a bear, father?”

“We do not send the arrow at the bear witch,” said the man. “It would not kill, but would anger the witch to great madness, and trouble—big trouble of much sickness—would come upon us all.”

Then came the strange voice of the squaw-man, and all of the others in the hogan listened closely as he spoke.

“Do my red brothers go with me to get the live bear when the sun is up to-morrow?” he asked. No one spoke for some time, and then an old man near the fire replied:

“We will go and make much noise with the drum and rattle, and will beat the ground with the sticks as you wish, but we will not help to catch the bear witch, nor send arrows at him. We do[51] not go if you are to kill the bear witch, and we go only near the bear cave; not close.”

“That is all that I ask,” said the squaw-man.

Suddenly there came a great noise from the other side of the man-house, followed by the loud barking of running dogs, and the snort of frightened horses. Running quickly toward the sheep corral, Wongo jumped over the low gate and made a grab in the darkness.

“What luck,” he thought, as he lifted an animal into his arms, and holding it tight around the neck he made off with it at top speed. But he had gone only a short distance when he discovered that there was something wrong with the sheep. It seemed too slick to hold easily and its legs and neck were longer than any of the sheep he had stolen before. Suddenly the animal began to squirm, and to kick and twist about in so vigorous a manner Wongo could scarcely hold it at all. It seemed to be all legs and feet.

It went through such rapid contortions that the little bear was forced to change his hold on it so many times he became confused in the darkness, and could not, for the life of him, tell whether he held the sheep right side up, or upside down. But that point was decided for him a moment later by the animal itself, who, with a sudden twist,[52] jabbed its horns so hard into his lowest ribs that he gave a grunt of anger and disgust.

“You are a common, cactus-eating goat!” cried Wongo, addressing the animal, “and it’s too late to take you back, and I can’t kill you here, or turn you loose,” he added desperately.

“Ba-ah-ah!” bleated the goat feebly, but loud enough to frighten Wongo into making a sudden grab for its neck, for he had been holding it tightly about the hind quarters, thinking he gripped it around the throat. With a great effort he swung the animal up on his shoulder, with head well forward where it could do no damage, and had started on with a fresh spurt of speed, when he suddenly tripped over a vine and down went bear and goat in a tumbling heap.

Wongo had sufficient presence of mind to keep a tight hold upon his prisoner when he fell. The goat, having turned a complete somersault, lit squarely on his feet facing Wongo, who, having but three feet to use, had fallen awkwardly in a sitting position on his haunches, one fore-leg extended with the paw tightly holding his prisoner back of the horns. Thus, although the goat could not go backward, nothing prevented him from going forward and, acting on the instant the thought came to him, he gave a lunge, head downward.

[53]“Woof!” ejaculated Wongo, as the animal’s head landed against the pit of his stomach, and to keep himself from going over backward with the shock of the blow, he was forced to use all four feet, thus giving the goat the chance it wanted. Off it sped like a white streak through the sage, and in an instant Wongo was in pursuit.

Confused with fear, the goat headed straight for the mouth of the canyon up which lay the trail. Having secured a little start of the bear, the goat was running for his life and making good time. Realizing that they were going in the very direction he would have to carry his prisoner anyway,[54] Wongo kept just close enough to the goat to frighten it into greater speed, knowing that once in the canyon the goat would stick to the path where there was fair footing, rather than attempt to plunge into the rocks or thick bushes on either side. On into the canyon sped the two animals; the goat, as Wongo had guessed, keeping to the trail. The goat was becoming less frightened. Had he not butted the bear over? Had he not run for some time faster than his pursuer could run? He was suddenly filled with confidence, and felt that he had a chance—a good chance—to get away from his enemy. As they sped upward, Wongo began to realize that they were nearing old Grouch’s patch of forbidden ground, and he had just caught the outline of the big, vine-covered rock, over which he was to jump after leaving his sheep, when he heard a savage growl from just ahead, and he suddenly realized that his old enemy had met them on the trail.

Stopping instantly, Wongo began to walk backward as fast as he could to the big rock, and as he did so he heard a surprised “Woof!” from out of the darkness ahead; a sound of tumbling in the brush; then a sharp clatter of small hoofs that seemed to retreat over the rocks far to the left of the trail.

[55]Jumping quickly over the big rock, Wongo ran at top speed around the side of the mountain. He had run but a little way when his sensitive nose told him that Kaw’s friend, the polecat, had kept his promise.

On ran Wongo, never stopping until he had circled the mountain and reached the flat-topped rock near his cave. He had scarcely stretched himself out for a short rest when he heard the flapping wings of Kaw, who flew up, singing as he came:

“Well,” said Kaw, as he ended the last line of his rhyme with a chuckle, “my crow friends and I surely aroused that peaceful little Indian camp in great shape. We flew so low and kept up such an uproar, the dogs followed us for half a mile, and we gave the squaw-man’s horses such a scare it is going to take all of the men about the place to round them up if they want to make an early start in the morning.”

Wongo then told Kaw of his adventures since[56] the crow had left him near the hogan, not omitting a single detail of his experience with the goat, nor of the final meeting with old Grouch.

At the end of the little bear’s recital the crow seemed so delighted he could scarcely contain himself for mirth. Dancing around, first on one foot then on the other and keeping a peculiar kind of time by flapping one wing against his side, he sang in a high key:

“Old Grouch will surely be out of luck to-morrow unless all signs fail,” he added, as he settled down into a more serious attitude. “Did you say that after you and the goat met old Grouch you heard the clatter of the goat’s hoofs as though he were running away?” he asked incredulously.

“Yes,” said Wongo. “When the goat met old Grouch there was a dull-sounding bump, and the old rascal gave a surprised grunt and seemed to thrash around a moment beside the trail. Then I heard the clatter of the goat’s hoofs on the rocks[57] at the other side, and he sounded as though he were going like the wind.”

“Well, well,” said Kaw, shaking again with mirth, “I never expected to hear anything like that, and I thought I was used to unexpected things, too. There is still work to be done before the night is over. It’s time you were warning the other bears on the mountain, and I must be off to find that goat and tell him how to get back to his friends in the corral below, before some night-prowling timber-wolf runs across him. He certainly has earned his life, and besides,” he added thoughtfully, “I may want to use him sometime and it’s just as well to do him a good turn as part pay for the service he unknowingly rendered us to-night. Have you many calls to make before your trip of warning is over?” he asked.

“A good many,” said Wongo. “There is old Mrs. Black, who has her cave about a mile above mine, the two Brown brothers who live over on the point, Mrs. Grizzly who lives with her two cubs over on the other side of the hill, and perhaps ten or twelve of our various friends who live across the valley, and I must not forget our friend ‘Long-ears,’ the crippled jack-rabbit, who lives in the brier thicket. The Indians might try an arrow on him.”

[58]“Needn’t waste your sympathy on him,” said Kaw. “He committed suicide last week.”

“Why!” exclaimed Wongo in surprise, “I can’t believe it. How did it happen? He was always such a good-humored rascal.”

“Well,” said Kaw, “he found a gray timber-wolf asleep in front of his den and, thinking it would be a good joke, he playfully kicked him in the ear!”

“Umph!” grunted Wongo sadly. “He was a droll fellow, but too thoughtless, I suppose.”

“Where will you advise our friends to go to-night?” asked Kaw.

[59]“There is only one good place where there will be food and plenty of water for all of us, and that is over the two ranges to the north.”

“Good place,” said Kaw. “Better than this, in fact. I know every inch of the big valley, and the stream there runs into a beautiful lake far over to the north, beyond the black hills. Let’s see, when the sun is straight overhead to-morrow, you will have reached the big aspen grove on the east side of the second mountain. I will meet you there and tell you all about the squaw-man’s big hunt for the live bear. I expect to watch the fun from the top of the tall pine that stands by the side of old Grouch’s cave, and if you were not so touchy about roosting, I might ask you to join me there,” he added with a grin. “But I will try and give you a full account of all that happens.”

And so the two friends separated, each to continue his night’s work.

WHEN the sun looked down from over the mountain the next morning it saw an unusual sight. A long, though peaceful, procession of bears, foxes, wolves, and even coyotes, went stringing along a dim trail leading toward the north.

A large herd of timid deer, sensing the fact that there must be danger somewhere, or the other animals would not be leaving the country at this season of the year, trailed cautiously in the rear.

Over the foothills and plains and little ravines traveled the procession, headed by Wongo. Through groves of big clean pine trees and over long stretches of sage-covered hills they went, never slackening the speed of their shuffling trot. It seemed to Wongo that it was the longest morning he had ever spent, and he was just wondering if the sun could be standing still, just by way of playing a joke on him, when on rounding a sharp point he saw the big aspen grove a little way ahead. Then he noticed that he was stepping[61] squarely on his shadow as he ran, and he could do that only when the sun was in the middle of the sky.

As they entered the edge of the first group of beautiful white trees, Wongo looked all around for Kaw, but it was evident he had not arrived, as he never waited for Wongo to look for him, as his sharp eyes could see the bear a long way, and he always knew where the bear was long before Wongo knew his crow friend was in the same neighborhood.

Weary with the work of the night before, and the long journey of the morning, the little bear stretched himself out luxuriously on the beautiful yellow carpet of the aspen leaves. He would rest a bit, he thought. He would not sleep—no, sleep was not to be thought of—for Kaw might come along at any moment now, and if he were asleep the crow might not find him. Shielding his eyes from the sun with his paw, he began to think of the experiences of the night before by way of keeping himself awake, but his thoughts wandered into a jumble of Indians with horns, goats on fire, and the squaw-man catching crows with arrows that had wings—a confusion of thoughts that led him into the land of slumber.

How long he slept he did not know, but he suddenly[62] became conscious that someone was speaking to him, or laughing at him, and he sat up with a jerk. On a stump a few feet away sat Kaw, going over his wing feathers with his beak by way of straightening himself up a bit after a long flight. He was mumbling to himself and keeping up, all the while, a low chuckle that occasionally rose to a laugh.

Seeing that Wongo was awake he said, “It is well that you take kindly to sleep, friend Wongo, as it is about the only thing that has ever defeated your curiosity.”

“Oh, I was just resting a bit while I was waiting for you to come,” said Wongo apologetically.

“Just resting!” remarked Kaw dryly. “So I have observed for the past twenty minutes.”

“Have you been on that stump for twenty minutes?” asked Wongo sheepishly.

“Yes,” replied Kaw. “Thought I had better let you sleep for a while. You and that goat must have had a ripping hard run last night. I didn’t find the poor animal until about daybreak this morning. He was dragging himself slowly down the mountain, many miles the other side of the canyon, and was the most forlorn looking beast I have ever looked upon. Although he looked quite thin and dejected, he still had some fire in his eye.[63] When the poor rascal caught sight of me he suddenly changed his limping shuffle into an upstanding walk, and attempted a swagger that was surely funny. I had considerable difficulty in persuading him that I wished to tell him how to get home, for he was going in exactly the wrong direction. After I told him a bit about your experience with him, he was so surprised that I should know of it he listened to reason quite readily. When I finally left him he was still holding to the swagger for my benefit, and as he disappeared in the brush I thought to myself, if he hasn’t been the boss of that sheep corral in the past he will be from now on.”

Wongo did not wish to be impolite enough to interrupt the crow’s recital about the goat, but he was fairly squirming inside with desire to know all about the squaw-man’s hunting trip. Seeing that the crow had finished his account of the goat, he asked:

“Did the squaw-man and the Indians go on their hunt? And did they find my trail? And—”

“One question at a time,” interrupted Kaw. “Now that you have told all of the other bears about our experience of last night, they will be as interested in the outcome as you are. Go call them, and I will tell the story to all of you.”

[64]Wongo lost no time in rounding up the other bears that had come with him, and all seemed eager to hear what had happened during the squaw-man’s hunting trip.

As the bears lined up in a row, Kaw took a commanding position on a low limb of a tree that stood just in front of them and from the half dreamy, half droll expression in his eyes, Wongo could see that his friend had something very interesting and perhaps humorous to relate. Pausing a moment for absolute quiet, Kaw began:

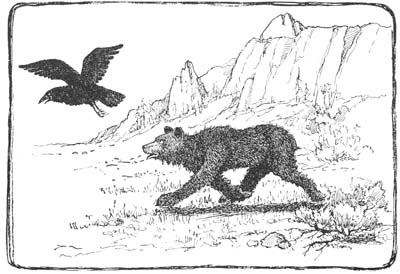

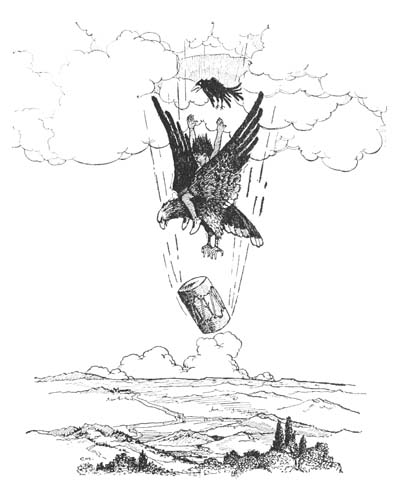

“It was just about daylight when I flew up to the tree near the den of old Grouch. I watched from my lookout for quite a long time and was beginning to get restless when I saw the hunters coming in long, single file. The squaw-man, with his dogs, was in the lead. He was holding the dogs back with thongs that were tied around their necks. The Indian men had rattles and tom-toms, though they made no noise. The boys had clubs and sticks and some had bows and arrows with which to shoot at small game. Far back of the squaw-man came the Navahos. They kept to the trail, and your tracks were very clear, Wongo, for they followed them easily. When they came to the place where you and the goat met old Grouch they stopped for a look. Then they ran back and[65] forth, and they whispered and talked. They looked all around and it was plain they were not sure about your tracks. I suspect the goat tracks confused them, for your trail stopped at the rock and bear tracks seemed ended while goat tracks went on. It got on my nerves when they started to gather about the high point where you jumped over the vine-covered rock, but just about that time the dogs got the scent of old Grouch and in no time the squaw-man caught sight of his den. He told the Indians to go around the den to the rear. He said, ‘When I signal, you start the big noise.’ Then he handed the leather rope that led his dogs to one of the boys.

“Well, soon all the Indians were back of the den, all ready to start at the squaw-man’s signal. Suddenly there broke loose a most unearthly noise. I have never heard anything like it. Talk about giving old Grouch a scare! Well, he was the most frightened animal I ever saw in my life. At first he let out a half-hearted growl, but that soon changed to a sound that was half whine and half yelp! In a terrible panic he started out of the cave and down the trail, lickety-clip, and I thought, now the hunter will use his gun, but he didn’t. He had in his hand what he called a rope. Then I thought, ‘Well, old Grouch, you’ve got a chance[66] to get away.’ One end of the rope was tied fast to a tree and I soon saw what the squaw-man was to do with the other end. He swung that rope around his head, and just what happened next I couldn’t see, for a cloud of dust arose just where the rope and old Grouch met! But when the dust settled enough to see—well!” and Kaw chuckled as he thought of what had occurred, and lapsed into rhyme as the only medium that would do justice to the occasion:

By the time the crow had finished, the bears were laughing until the tears ran down their cheeks. They danced with glee, and rolled over on the ground in fits of mirth, all of which was[67] thoroughly enjoyed by Kaw, who looked down upon them with a comical twist of his head that showed he felt fully satisfied with his adventure and the outcome.

After the noise of laughter had died down, Wongo, who was still curious as to the fate of old Grouch, asked:

“Do you suppose they got the old rascal into the cage thing, all right?”

“Well, I wanted to make sure of that myself,” replied Kaw, “so after I had had my breakfast, and a bath in the pool at the foot of the canyon, I flew out over the foothills to see what was going on. There were the squaw-man’s horses trailing along over the plain with the wagon thing rolling along behind them in a little cloud of dust. As I neared the wagon thing I saw our old friend Grouch, safely inside the cage, and pacing back and forth like a bee-stung bobcat. I could not resist having a bit of fun with the old beggar, so as I came up alongside I called out to him:

“I had to shout it out pretty loud to be heard above the rumble of the wagon, but he heard it, all right, and the way he looked at me was something[68] to be remembered. He growled and butted his old head against the sides of the cage thing in such a temper I said, ‘Oh, well, if you must be going, I won’t try to detain you any longer.’ Then I called out to him as the wagon rumbled away:

When the crow had finished the account of his farewell to Grouch, he flew slowly out over the hills, and Wongo was to see him no more until they would meet beyond the Black mountains to visit the cave of Cho-gay, the Indian boy.

THERE were several stories, each supposed to be a true account, of how Cho-gay, the lone Indian boy, came to live among the Black Hills of Timbertangle, a wild, secluded country, where no other man-animal ever had lived.

Probably Kaw, the crow, alone knew the truth. That wise old bird, who seemed to know almost everything, had told the animals how, several summers before, he had seen a curious brown spot floating[70] down one of the flood-swollen streams, clinging to a mass of brush. Upon investigation, the spot had proven to be a small Indian man-child and, when the brush had caught to a branch overhanging the stream from the shore, the little creature had finally crawled to land. From that day to this, Cho-gay had lived in Timbertangle, seeming to be as much at home among the animals as he could have been among his own people.

Where he had come from no one knew, but he was accepted on friendly terms by all—except the gray-wolf pack. He was looked upon as having strange power, that was, somehow, greater even than the power of tooth and claw, for his hands did many things that clumsy beaks and paws could not do.

Before the coming of Cho-gay, Kil-fang, the leader of the gray-wolf pack, had been the feared and despised ruler of the Black Hills, but Cho-gay had one day put secret fear into his heart. The wolf saw a strange deep look in the eyes of the Indian boy that he greatly disliked and could not understand. Twice had Kil-fang tried to make Cho-gay understand that he alone must rule among all the animal people of the hills, but each time Cho-gay had looked him in the eyes with that strange, steady gaze, and had walked slowly toward[71] him until the wolf had lost power to do anything but slink back, and back, and finally turn away. Thereupon this man-child had grunted and had made a quick snapping noise with his fingers, which somehow seemed to mean that he, and not Kil-fang, was the one with power to lead.

All this pleased the other animals greatly, for they loved Cho-gay, because they had learned that he was just, and they despised the great wolf, because he thought of nothing but to kill and eat. And now all knew that Kil-fang had found one who did not fear him—one who had greater power—and all knew that this meant that the wolf must leave the Black Hills with his pack or lose all power over it.

So, with jealous rage in his heart, Kil-fang had taken his followers into the north, vowing that he would return with a mightier pack, that would eat up the thin-skinned Cho-gay, and all others who might be so foolish as to dispute his power, or stand in the way of the wolf-pack.

Two winters had passed and, with these years of added strength and experience, the Indian boy had established a kind of rule and order among the animal people of the hills.

One morning, in the short sunny days of the fall, Cho-gay squatted on a flat-topped rock near the[72] entrance to his cave—a snug little hole at the base of a mountain—and scraped the fat from a fresh bobcat pelt with a sharp flint knife. As he labored he mumbled under his breath as if addressing the skin:

“I wouldn’t have killed you, old Short-tail, but the cold of the white frost comes soon, and the warm skin must be changed from your back to mine. Now that you have gone dead, you have no need of it, but as I am alive I can use it with much good. You were filled with the long years of much living, for I find very little fat on your skin, and you could have hunted not much longer—one more season, maybe. But I, I am young. Kaw says that no more than twelve winters have gone since I came to life, and I am filled with strength to hunt, and it may be I will have to fight, if the evil Kil-fang and his miserable pack come from the north to keep the vow Kil-fang has made. But Kil-fang is all growl, and is filled with much bragging talk; in his heart is fear, and it is fear of Cho-gay.”

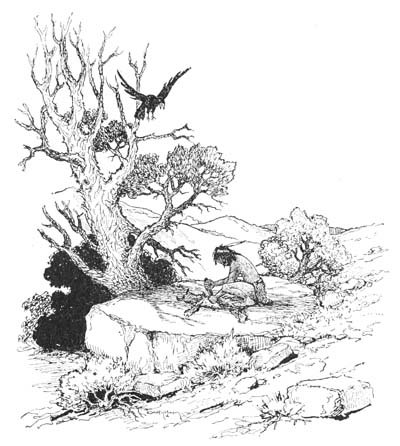

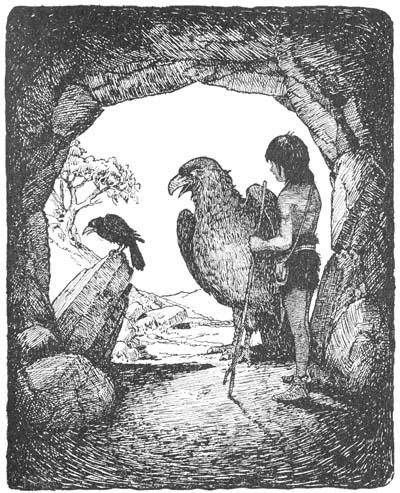

As a small black shadow flashed across the rock beside him, Cho-gay looked up in time to see a large black crow alight on the limb of an old juniper tree that stood near by. From this perch the bird looked down on the man-child, nodding gravely.

Cho-gay scraped the pelt of a bobcat with a knife

[74]“Welcome, Brother Kaw,” said the boy. “Many days have passed since you and I have met.”

[75]Kaw made no immediate reply, but looked steadily at the bobcat skin. Then, in a deep, serious voice, he said:

“So this is the end of old Short-tail—the most noble bobcat that ever robbed a grouse’s nest or gobbled up young crows. And Cho-gay, the friend of all animals, the leader of Timbertangle, has slain him.”

Although the Indian boy detected a teasing note in Kaw’s voice, the reference to his friendship for all animals produced an unhappy feeling within him, and rising to his full height on the rock he replied:

“The cold of winter comes; Cho-gay must have covering for warmth. There was no anger in my heart for old Short-tail. He was both old and lame, and is it not wiser that I have his skin for good use than that it should be in the greedy stomach of Yap-kii the coyote? Soon he, or one of his family, would have hunted him down and eaten him.”

“Yes,” said Kaw, solemnly, “what you say may be true, but he was such a good friend of all birds. He would do most anything for them. How he loved them!” Then in a sad voice he sang:

At this Cho-gay grinned, for he had half-feared that beneath the mock sadness of his friend was a rebuke for what he had done.

“To kill only where there is great need is an old law of the hills. This you taught me yourself when I was yet very little, and I do not break the law,” said Cho-gay.

As he squatted down again to resume his work, a soft pad, pad of broad feet was heard coming down the trail that led along the mountain side, and Kaw remarked, “Here comes our friend Wongo, the bear. I’ll wager that curiosity or hunger brings him here, for he always is filled with curiosity, even when empty of food.”

Cho-gay looked over his shoulder as the little bear came up, and called out, “Welcome, brother Wongo! Had you come sooner you would have heard a good rhyming talk from the mouth of our friend Kaw. It may be that he will again say it.”

“Welcome, Brother Kaw,” said Cho-gay

[78]“If the rhyming talk was the kind he makes about me, I don’t think I missed much,” said the little bear crossly. Then, as he seated himself on the rock, he caught sight of the bobcat skin, and with eyes wide with wonder he exclaimed:

[79]“Who is it that leaves his hide for another to use? Did you kill him in a fair fight, or in a trap? Was he—”

But the voice of Kaw broke in before the last question was finished:

“Well, if that’s the kind of silly talk you were making before I came, I’m glad I did not hear it,” said Wongo.

“It’s too bad you can’t appreciate the work of a real poet,” said Kaw sadly, “but I suppose when one is hungry his judgment is affected.”

At a sudden noise, half bark and half whine, that came from a point a little above the cave’s entrance, Cho-gay rose, picked up a handful of the fat that had been scraped from the skin, and went up to a flat rock on the hillside. Moving the stone ever so little, he called out:

“Stop the noise, you little sharp-nosed thief! Your whining will bring all the fox family here to ask questions why I have shut you up. Here is[80] all you get this day,” he added as he tossed the fat through the crack. “Many days will go before you are out. Twice you have been a thief, and this time you will be a long time behind the rock so that you will learn that it is not good to steal the dried meat from Cho-gay.”

Kaw and Wongo watched this performance with great interest, and the little bear wanted to ask many questions, but he feared the teasing remarks that would surely follow. As it turned out, he heard all that he wanted to know without asking.

After the fox had been silenced with the scraps of fat, two other prisoners were visited and fed; one an old mountain sheep, and the other a young bobcat. At the hole, or small cave, where the sheep was confined, the Indian boy spoke to his prisoner:

“Old Twisted-horns, three more days and you will again run over the hills as honest people run, but if you again steal corn from me your skin will become a covering for the floor in the cave of Cho-gay.” The old sheep made no reply, but ate what was given him in sullen silence.

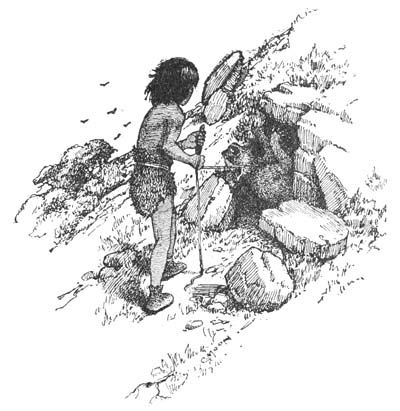

At the prison of the bobcat the Indian boy peered in through the crack beside the slab of rock that served as a door, and then picked up a rope of stout buckskin that ran into the prison from the[81] outside. As he pulled it there came an angry snarl from within.

“So!” exclaimed Cho-gay. “You are still filled with anger. I will not take the rope from your neck until you speak more softly. I know the hole is too small for you, but here you shall remain until old Twisted-horns is free. Then you will go into his house, but you shall not be free until Cho-gay has taught you to keep the laws of Timbertangle.”

As he returned to his work in front of his cave, the Indian boy remarked to his callers, “While Cho-gay lives in the Black Hills all thieves that are caught will be made to obey the law of the hills. There was great anger in Big-paw, the cat, when he caught himself in the rope trap, yet he was stealing meat from my cave when the rope went round his head. When I came he wanted to fight, but a twist and a quick pull, and Cho-gay had him without breath to snarl. Now he shall not go free until the hunger in his stomach has eaten up his anger. They that steal shall be punished. Is it not a just law, my brothers?”

“It is just,” said Kaw.

“Yes, it has the sound of being just,” said Wongo, “but when there is hunger and poor hunting, the hunter must have food.”

[82]At this remark, Kaw cocked his head on one side and looked keenly at the little bear. Then he said, “About an hour ago, while I was flying over the twin hills, I saw an aged mountain sheep who had been driven from the flock by the young rams.”

“Where was that?” asked Wongo eagerly, as he got to his feet.

“On the cliffs above the aspen trees, on the south side of the first hill,” said Kaw.

Scarcely were the last words of the crow spoken before the little bear was speeding away toward the place where Kaw had seen the sheep.

“I have sharp eyes,” said Cho-gay, addressing the crow, “but how is it that you have eyes that can see hunger in the stomach of a bear?”

“Have you not learned that hunger makes all of us cross? It is only when our friend Wongo is very hungry that he is cross, and we do not have to see crossness. We sometimes hear it. Hunger will not take the anger away from Big-paw, the cat. If you feed him and give him more room he will soon lose his anger,” continued Kaw, “and it is because he is a captive, and not because of hunger, that he will learn to be honest.”

“Your words have the sound of wisdom,” said the Indian boy, rising, “and I shall see if they are not true.”

Going up to the flat rock that covered the entrance to the prison of the old mountain sheep, he rolled it to one side. A moment later the astonished sheep leaped out and dashed away up the side of the mountain. Kaw watched this performance with[84] keenest interest. Passing on to the prison of the bobcat, Cho-gay picked up the buckskin rope with one hand and drew his knife from his belt with the other. Then pulling the flat stone from the mouth of the hole he gave the rope a sudden pull. The bobcat came tumbling out, and before it could regain its feet it was dragged to the former prison of the mountain sheep, too dazed to realize what had happened before it was in new quarters and the stone door lifted into place.

“Very quickly and neatly done,” said Kaw, in admiration. Then he added in a low tone to himself, “Our friend Wongo should have good hunting to-day, for if he should miss the old sheep on the cliff, he will surely get old Twisted-horns, who is making for the same place.”

As the Indian boy returned to his cave to get food for the young bobcat, there arose the sound of many yapping voices from the sagebrush below.

“News! News for Brother Cho-gay!” came the voices. A thin, sharp-nosed coyote emerged from the edge of the sage and stood a little in the open, as though he feared to come nearer. Then the heads of three or four of his followers were poked from the brush, as though to lend support to their timid leader, and to see the great man-child to whom their remarks had been addressed.

[85]“News is of no use until it is told,” said Cho-gay. “Speak up, Brother Fearful. What is there to tell?”

“Is it not a law among us that if one makes a lie, and tells it against a brother, he shall be punished?” asked Fearful.

“It is a law,” replied Cho-gay. “Who is it that breaks the law?”

“It is Sandy, the red fox, who has made a great lie, saying that he has flown like an eagle from the valley to the top of Skull-top mountain, and that as he left the top to come down, a rock fell and rolled down to the valley. And that our old cousin, Rip, the outcast wolf, who is very brave, ran in great fear, believing that the mountain was tumbling down. So our cousin Rip is made a coward in the eyes of all, because of the lie.”

“Where is your cousin Rip that he does not come to accuse the fox?” asked Cho-gay.

“He and Sandy hunt together, and he is afraid to make Sandy angry. Why, we know not,” answered Fearful.

At the sound of a chuckle from the juniper tree, Cho-gay looked up to see Kaw shaking with laughter. Paying no heed to this, he again spoke to the coyote:

“All know that a fox cannot fly through the[86] air to a mountain top. Go, bring this maker of lies to me and we shall hear his story from his own mouth.”

This order was evidently what the coyotes wanted, for they quickly vanished into the brush.

When they had gone, Kaw could scarce contain himself for mirth. Anticipating the scene that would follow when Sandy, the fox, faced Cho-gay, he hopped up and down as he sang:

As the old crow spread his wings to depart, Cho-gay asked, “Does that rhyming talk mean that a fox might fly?”

“It might!” said Kaw from over his wing as he flew away.

IN THE afternoon of the day following the visit of the coyotes to the cave of Cho-gay, a dapper little red fox and a gaunt, one-eyed, old timber-wolf trotted over a narrow trail that led along the rim of a canyon.

They were Sandy, or Red-eagle Fox, as he loved to call himself, and Rip, the veteran outcast of a once great pack. Why this strange pair hunted together was a mystery to all but Kaw, the crow. He knew that it was because the conceited little fox, who never tired of boasting of his supposed skill as a hunter, felt it a great compliment to be permitted to hunt with a real wolf, and that old Rip endured the companionship of the boastful little fox for the simple reason that when game is to be found, two sharp, young eyes are better than one old one. In truth, the old wolf knew that his days of hunting alone were gone.

The alert little fox, filled with false pride and great vanity, formed a strange contrast to Rip, for[88] even a casual observer would have noticed that the old wolf had passed a long way beyond the prime of life. Old Rip’s left eye had been lost in one of the numerous battles he had been called upon to fight, but the right eye still retained some of its former fire; a part of one ear was missing, but he could hear with it very well. As he ran, it could be seen that his joints were not just as limber as they once had been. His greatest characteristic was an insatiable appetite; he was always hungry. But, in spite of all this, he was a wolf, and that fact made him great in the eyes of Sandy, the fox.

While on hunting trips, the luck of this strange pair was a very uncertain thing, but usually the little fox managed to catch a rabbit or some birds, and old Rip was always careful to pay his partner some gruff compliment before devouring the larger portion of the game.

Secretly Kaw enjoyed the fox and wolf, as they afforded him many a quiet chuckle, of which they were ignorant. Because of his interest, Kaw frequently helped them to find game when hunting was poor, and the two learned to look upon him as a valued friend.

On this particular afternoon, the hunters were in no pleasant mood, for it was growing late and they had killed nothing since early morning but a small grouse, which did not satisfy their appetite for long.

Sandy, the fox, and Old Rip, the timber-wolf

[90]As they stuck close to the trail, it was evident that, though hungry, they were on some business other than hunting.

[91]“How much farther is it to this bear’s den?” growled Rip, who was beginning to weary of the journey.

“Only a little way now,” replied the fox. “Soon we will go up the mountain side a short distance, and then we are there.”

The old wolf made no reply to this, but trotted doggedly along after his companion. Wishing to turn Rip’s thoughts to less tiresome things than trails and distances, the little fox asked, “How did you learn that Kil-fang and his pack are returning to the Black Hills?”

“I have ears, haven’t I?” growled Rip. “When there is news of a kill abroad, I hear of it, and there will be good hunting for many of us when the pack comes down the north canyon. All animals will run over the hills to the broad valley to get out of the way of Kil-fang, and it is there I shall be before them.”

“I also will be there,” remarked the fox, and each of these brave hunters had visions of the great number of rabbits, squirrels, and small[92] animals that would swarm over the hills and into the valley to the east, as the wolf pack came through the canyon that opened into the Black Hill region on the north.

“When does the pack come?” asked the fox.

“Yap-kii, the coyote, gave me the news,” replied Rip, “and he says the pack now numbers more than fifty, and that they will come into the Black Hills when the moon is again at the full. I have no liking for this Cho-gay, but I have less for the strutting Kil-fang, and I shall howl the death howl with great happiness if the Indian man-child kills him and drives his boastful pack again into the north.”

“It is not many days from now that the moon is at the full,” said the fox, “no more than a dozen, at most. Does anyone but Yap-kii and you know about the coming of the pack?”

“No one,” replied Rip, “for he does not dare to tell Fearful and his brothers, as they talk too much, and the rabbits and squirrels have sharp ears.”

Suddenly a voice that came from the limb of a cottonwood tree above their heads called out:

At the sound of Kaw’s voice, for it was he, the spirits of the two hungry hunters began to rise, for now there was hope of finding something to eat.

“Where are we going, so far from home, on so fine an afternoon?” inquired the crow. Then without waiting for a reply, he continued, “I’ll guess you are just out for a quiet stroll after eating a nice meal of fat mountain sheep and jack-rabbit.”

At the mention of such delicious food old Rip licked his chops, and the little fox squirmed uneasily. As usual he spoke for the two:

“We certainly would have had a fine meal if we had been on one of our regular hunting trips, for as you know I always bag my game, and there is no greater hunter than—”

“Then you have had poor hunting to-day?” broke in Kaw, who did not care to hear the boastful remarks that he knew the little fox was getting ready to make.

“Yes, that’s just it,” replied the little fox. “As[94] I was saying, we are on our way to make an important call, and though we have come a great distance, there has been nothing good to eat within sight or sound of us since dawn.”

At that moment the keen eyes of the old crow caught sight of a short line of moving animals far back along the canyon rim, but though his eyes twinkled as he realized that Fearful and his brothers were trailing the little fox, to tell him of Cho-gay’s order, he said nothing to the two hunters, who were ignorant of the fact that they were being followed.

“Well,” said Kaw, “as I flew over the sage that is just around the point ahead of you, I saw a number of jack-rabbits that were headed up the mountain. If you cut in above the trail you will head them off!”

Instantly the two hunters sprang forward toward the place indicated, each trying to be first, and neither remembering to thank the old crow for the information he had given them.

“So they are making an important call,” said Kaw to himself, as he watched the odd pair loping away up the mountain side. “It’s quite plain who they are calling upon. I wonder what kind of a plot is in the wind now.” Then he looked back far down the canyon trail, where the small line of[95] coyotes were slowly approaching, and chuckled to himself as he flew off over the mountain.

Less than half an hour later, Rip and Sandy had managed to kill two jack-rabbits, and were trotting along the well-worn little trail that led to the cave of Wongo, the bear. Suddenly the fox, who was in the lead, stopped beside some jack-oak bushes and spoke to his companion:

“You can wait here, friend Rip, while I talk to Wongo, for you see he must not know that you are in this plan of ours. If he learns that you are interested in the escape of the mountain sheep, or I should say in eating the sheep after it has escaped, he would tell Cho-gay. If this Indian man-child hears of it, you would never get the sheep, and my brother might not be set free in time to escape Kil-fang and his pack.”

“I keep my word,” replied Rip, who was in a better humor after the meal of the jack-rabbit. “But remember,” he added warningly, “I am to have the mountain sheep in return for telling you the news of Kil-fang and the pack. Go on; I’ll wait for you here.”

Sandy trotted up the trail, leaving his companion, who was glad enough to rest his weary bones after so long a journey.

A few minutes later the fox, after announcing[96] his presence with a short bark, poked his head into the bear’s cave and called out, “A good evening to you, Brother Wongo. I hope I am not interrupting a nap.”

“No,” replied the little bear, who was suddenly curious to know why Sandy was so far from his own hunting grounds, “but I am just getting ready to take a walk into the canyon. What brings you to the cave of Wongo?”

“I have just been on one of my famous hunting trips,” replied Sandy. “I often make long journeys when in search of big game, for, as you may know, I am one of the greatest—”

“All right,” cut in Wongo, who had learned from Kaw about Sandy’s habit of boasting, “but what brings you here?”

“As I was just saying,” replied the fox, “I was passing this way, and thought I’d just drop in to see you, and perhaps ask a question or two that you might be able to answer.” Sandy looked anxiously at the little bear.

“Go on,” said Wongo, whose curiosity was growing.

“I have just heard that you visited the cave of Cho-gay, the man-child, yesterday, and it may be that you can tell me something about him. They say that he has many animals that he keeps as[97] prisoners in little holes in the rocks near his cave, and that he does not let them out. Is it so?”

“He has only three animals,” replied Wongo, “and he keeps them shut up because they steal, and so have not kept the law. One is a mountain sheep, who stole his corn, another is a young bobcat, who stole or tried to steal dried meat from his cave, and the third is a fox who has twice stolen from him, but will not steal again very soon.”

The little fox remained silent for a few moments, not knowing just how to gain the real information he had come for, but just as the impatient Wongo was about to ask him to go on, he remarked, “All say that this Cho-gay knows all animal talk, that he can do strange things, and that he carries a long, sharp claw with which he can kill very quickly when he wishes to. Is it so?”

“That he can do strange things is true, and the thing you call a claw is a knife,” said Wongo, and he took on a superior air as he gave this information, for he was quite proud of his knowledge of Cho-gay.

“Could he kill the gray-wolf pack if it should come?” asked Sandy.

“That is a silly question,” replied Wongo. “No one could kill the pack single handed, unless[98] he had as many heads and as many teeth as the pack, and of course we know that no such animal lives in Timbertangle.”

“Would Cho-gay shut me up if I went to tell him something he would like to hear?” inquired Sandy.

“No, if what you tell is true. But why not tell me, who knows him, and I can tell him for you,” suggested the little bear, whose curiosity was now thoroughly aroused.

“No,” replied Sandy, “I have reasons why I must tell him myself; I have valuable information to give him and—well, it may be that I will ask him for something in return.”

“Oh, very well,” said Wongo with pretended indifference. “I can’t see that the matter concerns me, so I will bid you good——”

“Yes, yes!” broke in the fox quickly, “It does concern you, as I want you to take me to this Cho-gay, for I have never seen him except from a great distance and—well, you could tell him who I am, you know, and that we are close friends, and about my reputation as a great——”

“Ho, ho!” grunted Wongo. “You mean that we are acquainted because we both happen to be friends of Kaw, the crow.”

“Just that,” said the fox, who wished to be very agreeable to the little bear. “By the way, did you[99] happen to hear Cho-gay say just when he expected to free the mountain sheep and the fox?”

“Yes,” replied Wongo, who was anxious to show his caller that he knew a great deal about the doings of the ruler of the Black Hills, “I heard him say that the mountain sheep is to go free in three days, that’s the day after to-morrow, but the fox is to be kept for a long time, as he is a great thief and has twice broken the law.”

The little fox squirmed uneasily when the last statement was made, but his uneasiness escaped the notice of the bear.

“But what has all that to do with the great secret that you have to tell Cho-gay?” asked Wongo.

“You will learn all that if you will just agree to accompany me to his cave, and if you would—well, just tell him that I am Red-eagle Fox, the hunter.”

Wongo made no reply for some time, merely for the impressive effect his silence would have on his caller.