by

Patti Carr Black

an exhibition

at the

Mississippi State Historical Museum

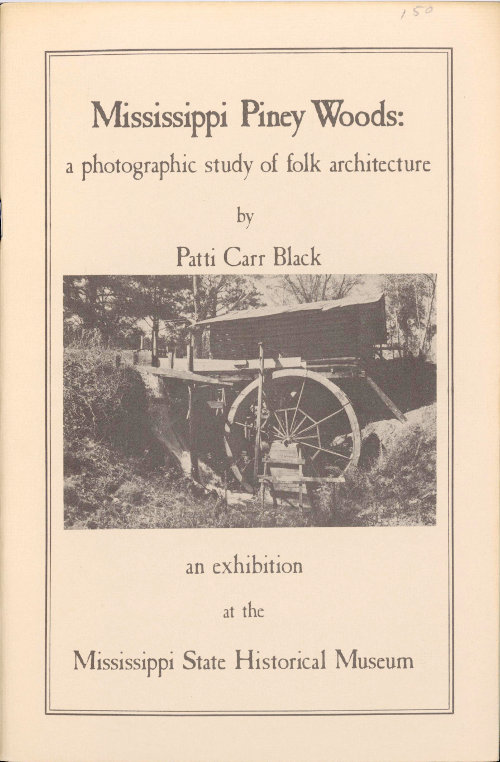

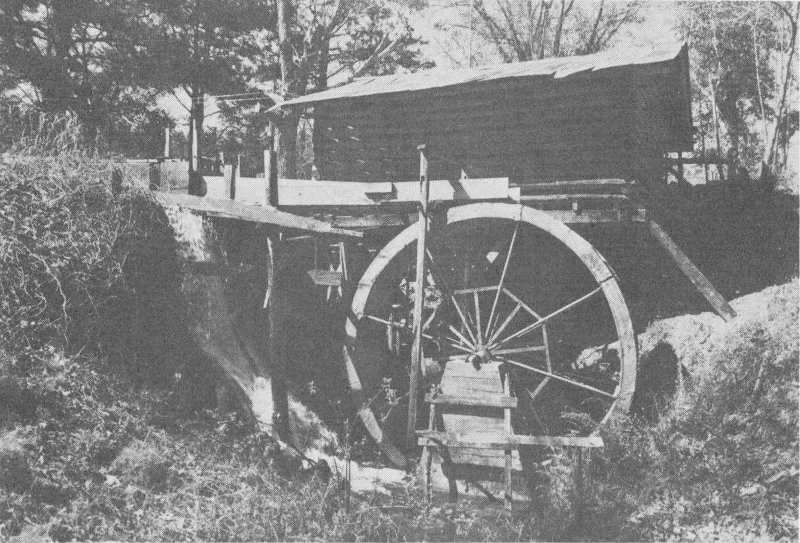

Cover photograph: Grist mill at Lake Bounds, Clarke County

by

Patti Carr Black

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Jackson, Mississippi

1976

Reprinted 1980

My appreciation and thanks to the many residents of the Piney Woods who gave me directions, information, and access to their homes, especially Miss Gertie Ainsworth, Hulan Purvis, Bob and Patricia Harris, Clarence Smith, Charles A. McGee, S. D. Sullivan, and Mrs. L. E. Turner.

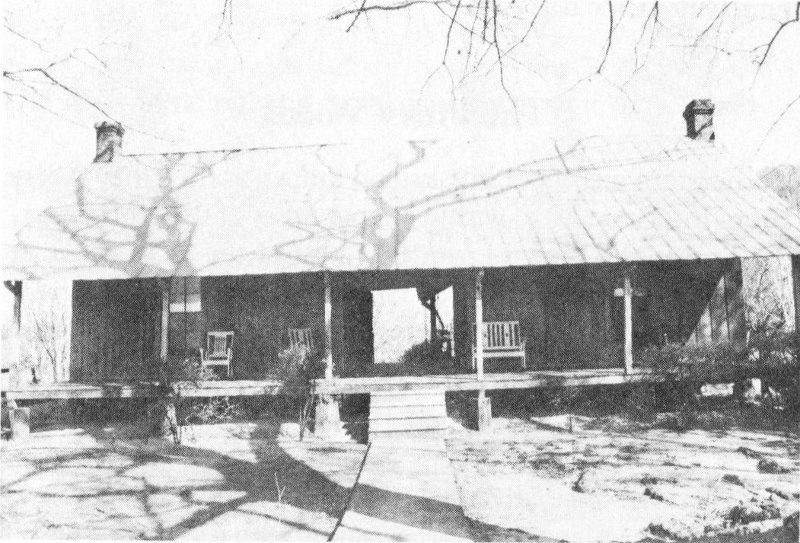

Opposite: Sam Hosey house near Moss, Jasper County

“Then a house appeared on its ridge ... as if something came sliding out of the sky, the whole tin roof of the house ran with new blue. The posts along the porch softly bloomed downward, as if chalk marks were being drawn, one more time, down a still misty slate. The house was revealed as if standing there from pure memory against a now moonless sky. For the length of a breath, everything stayed shadowless, as under a lifting hand, and then a passage showed, running through the house, right through the middle of it....” —Eudora Welty

The dogtrot house described by Eudora Welty in Losing Battles is in every Mississippian’s memory. Dogtrots, a part of the Mississippi landscape since the early 19th century, were one of the most popular forms of folk structures in the state, particularly in the southeastern section.

The study of folk architecture has been largely ignored in Mississippi, with the major attention going to large mansion houses. Even the term “antebellum” has been used to refer only to affluent homes. Many dogtrots, log houses, and other rural homes in Mississippi are antebellum (built before the Civil War) and are far more widespread and characteristic of 19th century Mississippi architecture.

The houses built by the pioneers themselves represent an important and basic element of Mississippi culture. They reveal the ingenuity and courage and affirmation of men and women who built their homes with little money, limited materials, and no formal training as architects and builders. Few of these structures are left standing in their original form and every day brings the destruction of more. This study is intended to be a sampling, not an exhaustive survey of Piney Woods folk architecture. It was undertaken with the support and encouragement of Dr. Byrle Kynerd, director of the Mississippi State Historical Museum and Dr. 4 William Ferris of Yale University and was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

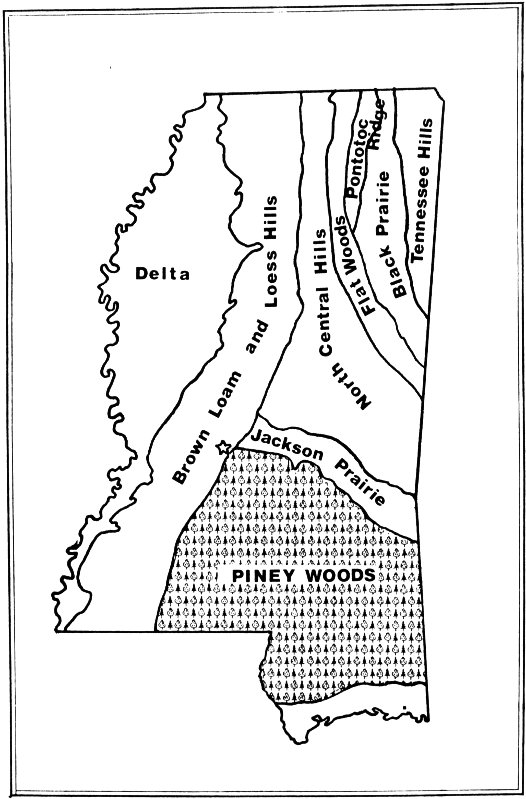

The southeastern quarter of Mississippi, known as the Piney Woods, extends southward from Interstate 20 to within twenty miles of the Gulf Coast, and from the Alabama line to the Brown Loam Belt west of the Pearl River. It is a high rolling land, once covered by dense stands of long-leaf pine, and patches of hardwood in the bottoms. Numerous rivers and creeks criss-cross its sandy soil. The Leaf and Chickasawhay form the Pascagoula River that empties into Pascagoula Bay. The Pearl River, with its tributaries, the Strong and the Bogue Chitto, empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

The Piney Woods, originally inhabited by the Choctaw Indians, was ceded to the United States by a series of treaties beginning with the Treaty of Mount Dexter in 1805. In the great migration after the War of 1812, settlers began coming in by horseback, on foot, by wagon teams, moving west across the Fort Stephens-Natchez road and the Three-Chopped Way and down Jackson’s Military Road. They came by flatboat down the rivers, and later by steamboat up the Pearl. They came from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Tennessee to the land described by J. F. H. Claiborne in 1840 as “covered exclusively with the long-leaf pine; not broken, but rolling like the waves in the middle of the great ocean. The grass grows three feet high and hill and valley are studded all over with flowers of every hue.”

The pioneers of the Piney Woods were not agriculturists. They were primarily livestock graziers and hunters, whose chief interest in the land was to have a place for a cabin, a few out-buildings and stock pens, small corn and vegetable patches, and open range for their livestock. In 1870 William H. Sparks of Natchez wrote about the settlements in the Piney Woods. He said they “were constituted of a different people (from the agricultural population farther west): Most of them were from the poorer districts of Georgia and the Carolinas. True to the instincts of the people from whom they were descended, they sought as nearly as possible just such a country as that from which they came, and were really refugees from a growing civilization consequent upon a denser population and its necessities. They were not agriculturists in a proper sense of the term; true, they cultivated in some degree the soil, but it was not the prime pursuit of these people, nor was the location sought for this purpose. They desired an open, poor, pine country, which forbade a numerous population. Here they reared immense herds of cattle, which subsisted exclusively upon coarse grass and reeds which grew abundantly among 5 the tall, long-leafed pine, and along the small creeks and branches numerous in this section. Through these almost interminable pine forests the deer were abundant, and the canebrakes full of bears. They combined the pursuits of hunting and stock-minding, and derived support and revenue almost exclusively from these.”

Gradually, in the second wave of migration, farmers began moving into the Piney Woods, men who desired the ownership of the land rather than its free use. Older settlers began to decrease their herds and increase their fields, but by 1860 still only a fraction of the land was “improved land.” Because the soil was poor and the farms tended to be small, the plantation system and slavery never thrived there. The number of slaveowners were few and the Piney Woods has remained predominantly white.

In the closing decade of the 19th century, the railroads opened the country to the lumber industry. Northern lumber companies bought vast areas, sawmills were established, lumber towns sprang up. In less than thirty years the great pine forests were stripped, ghost towns were left, and the stumps of cut-over land attested to the ravaging of the forests. Reforestation has restored much of the land to loblolly-shortleaf pine forests, and industrialization is slowly changing the character of the Piney Woods.

Because of the availability of trees, log houses were the most common type of house built in the Piney Woods during the 19th century. The most typical style, still found today, is the “double-pen” construction, also called “dogtrot” or “two-pens-and-a-passage.”

Scholars disagree on the origin of the dogtrot. Some have attributed it to Scandinavian influence, while others have shown a close relationship to the double-pen houses of Africa. Henry Glassie has suggested that the dogtrot developed in the lower Tennessee Valley around 1825. However, a description of a dogtrot in Mississippi as early as 1789 has been recorded. In Narrative of a Journey Down the Ohio and Mississippi in 1789-90 (Cincinnati, 1888) Samuel S. Forman of New Jersey described his uncle’s house that he visited on a plantation bordering St. Catherine Creek, four miles from Natchez:

The place had a small clearing and a log house on it, and he put up another log house to correspond with it, about fourteen feet apart, connecting them with boards, with a piazza in front of the whole. The usual term applied to such a structure was that it was “two pens and a passage.” This connecting passage made a fine hall, and altogether gave it a good and comfortable appearance.

It seems probable that the dogtrot construction was a natural physical development, possibly happening in various countries simultaneously. Shorter 6 logs or timbers were more easily handled and the size of a cabin possibly was determined by the length of logs the builder could handle. Later when an additional room was needed, the corner timbering of the log pen made it impossible to butt the units together. The space left between the pens was made wide enough to be useful.

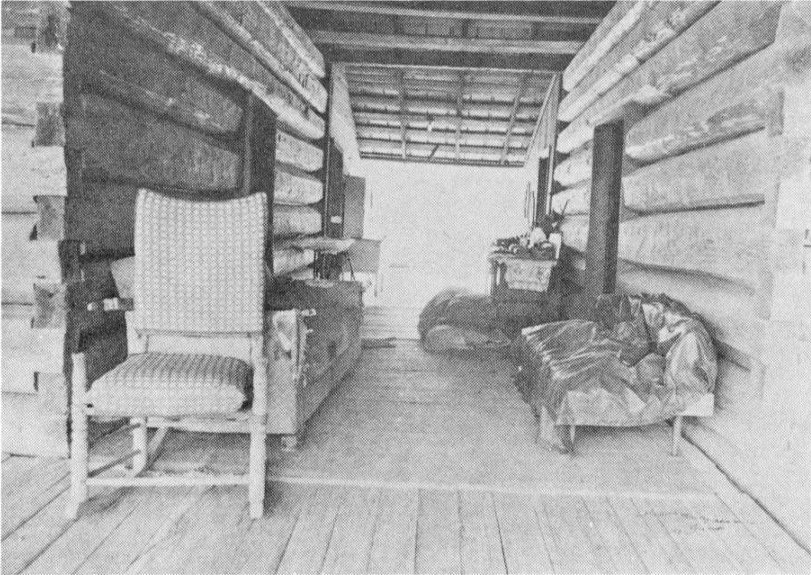

All of the log dogtrots studied in the Piney Woods were built in stages, following the same pattern. The settler built a one-room log house or “pen.” Later, as his family and fortune increased he built an identical log pen and connected the two with a common roof, leaving a passageway or “dogtrot” between the pens and providing an overhang for porches front and back. One pen usually served as a kitchen and living room and the other as a bedroom. The covered passage formed an area for household activities, children’s play, and a cool sitting spot for summer evenings. Today the passageway is more likely to house the “deep freeze.” As the family grew and more rooms were needed, the sides of the front or back porch were walled off and called “shed rooms” or “drop sheds” (Fig. 1).

All log houses were not dogtrots, and dogtrot construction was not limited to log houses. Many later frame houses were built in the popular style. When Hulan Purvis of Rankin County decided to build a frame house for his family in 1910, he emulated the construction of his father’s dogtrot, using the same type of “long-strawed” pine, but pine that had been planed at the sawmill rather than hewn by hand (Fig. 23).

Many of the early dogtrots have been remodelled, enclosing the passageway for a central room (Fig. 25). Others have been abandoned or destroyed. Not all houses with open passageways are dogtrots. The Bob Goodloe house in Smith County is an example of a non-dogtrot because the two sides of the house are not of equal size or symmetrical relationship (Fig. 26).

The only tool a man actually needed to build a log house was an axe. With an auger, an adze, a drawing knife, a froe and maul, a broadaxe, or saw, he could build it more efficiently. Tools and building techniques were passed down from generation to generation. One such technique enabled a man to raise the walls higher than he could lift a log by placing two logs at an angle against the wall to serve as a skid and using forked sticks or ropes to guide the logs into place.

Another technique was splitting logs by standing them vertically between scaffolding and sawing downward, lowering the scaffolding as the log was cut.

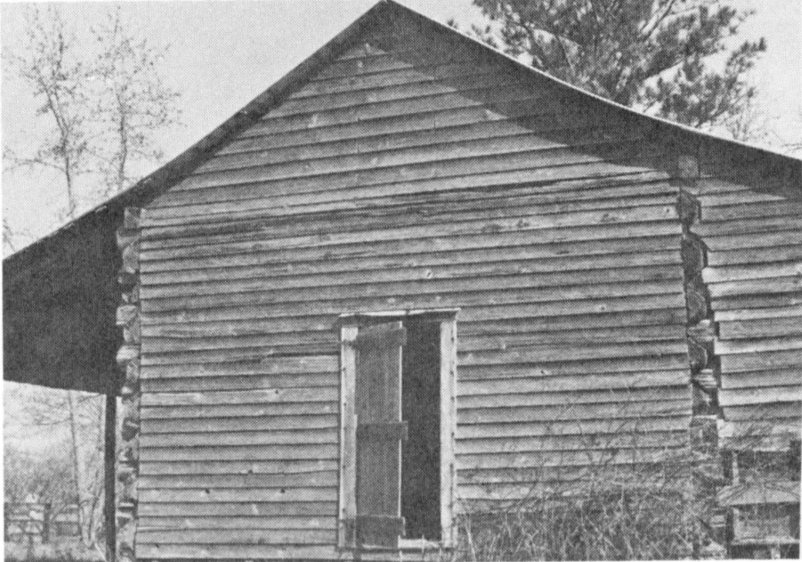

1. Sullivan House, near Mize, Smith County. Built 1810-20 by Tom

Sullivan in “Sullivan’s Hollow.”

Present owner: Shep Sullivan

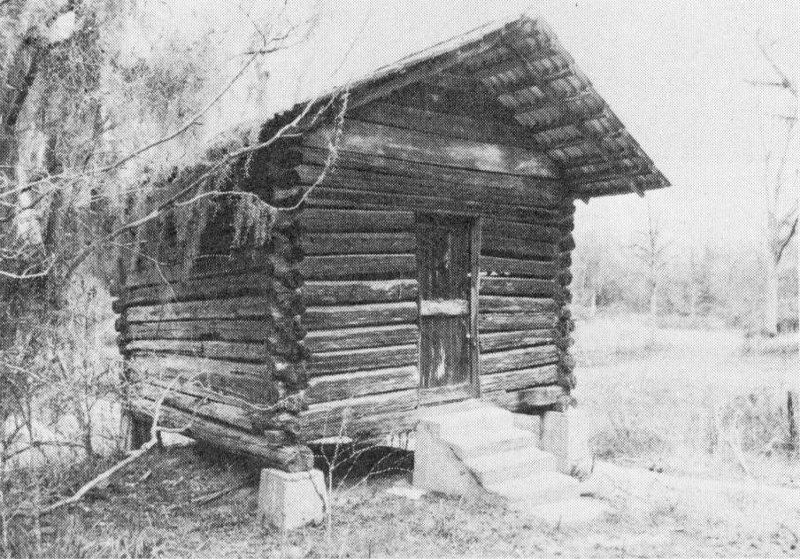

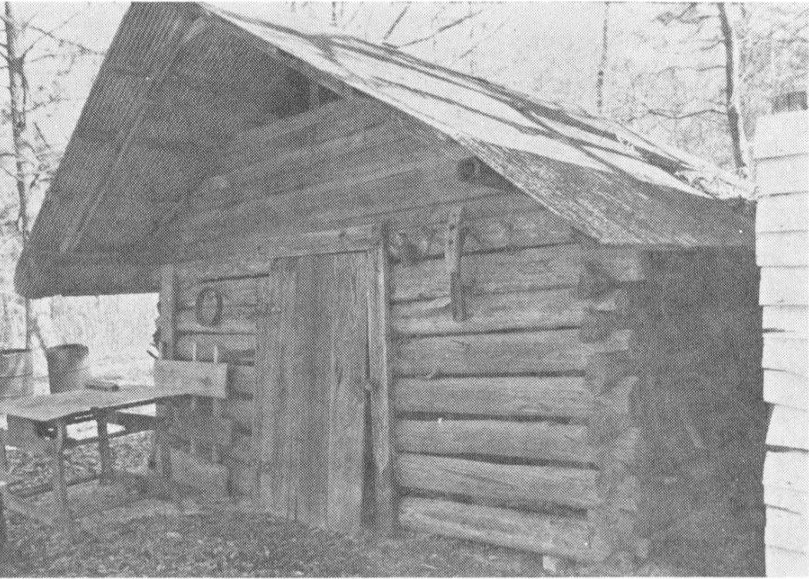

2. First sheriff’s office, Pike County. Built in 1815 by Laban Bacot.

Present owner: Mrs. Lloyd Hamilton

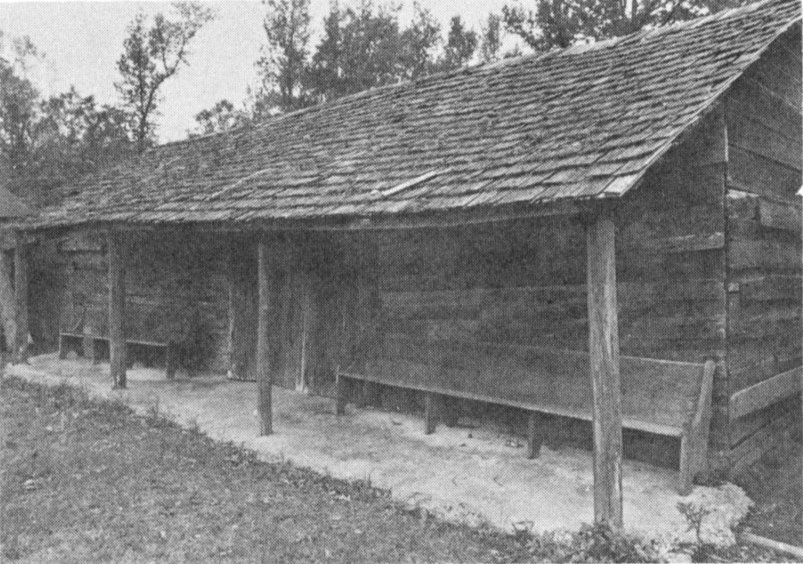

3. John Walters cabin, Rankin County, 1860s.

Present owner: James Huff

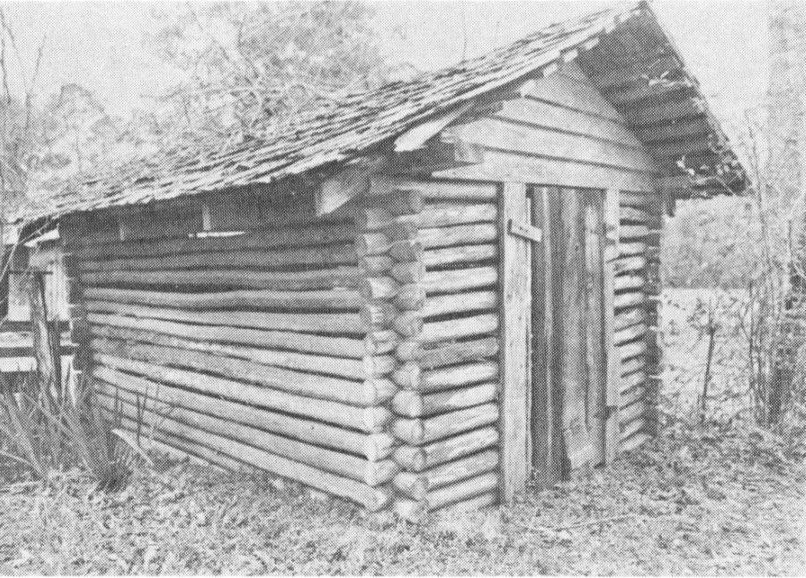

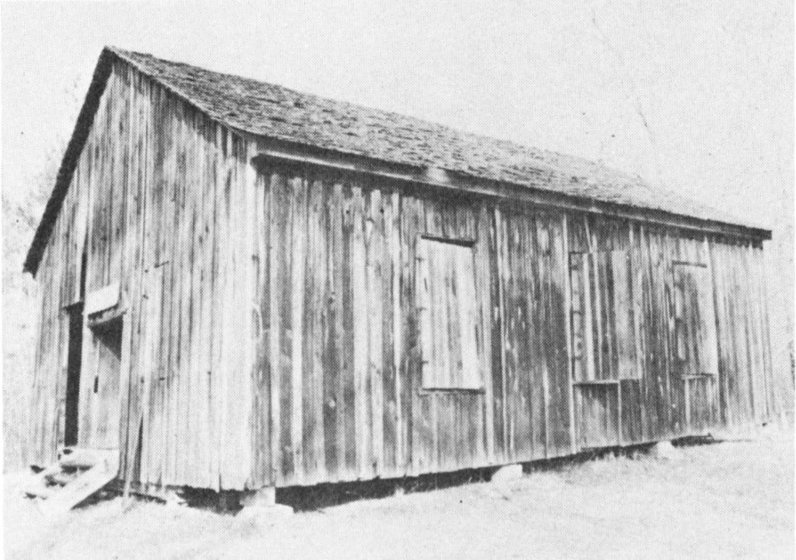

4. Tool shed, Walthall County.

Present owner: George Wingo

5. Blacksmith shop, Lake Bounds, Clarke County, ca. 1900.

Present owner: Mrs. Gertrude Gatlin

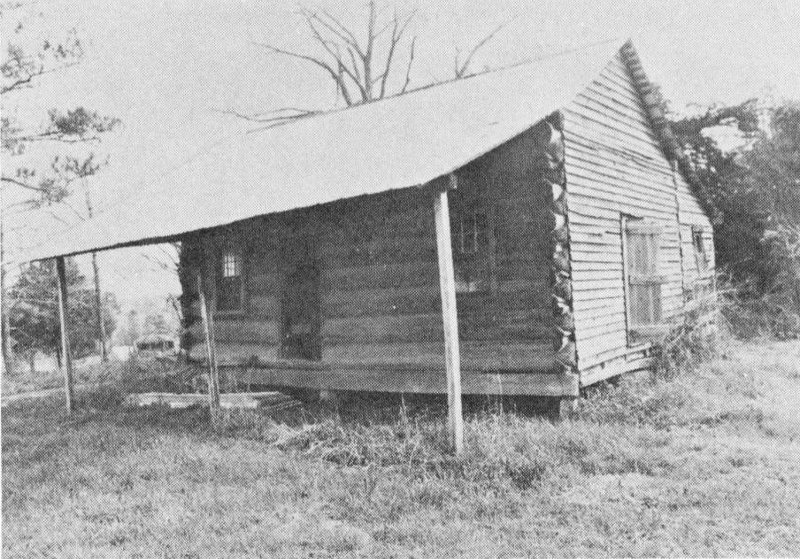

6. Jonathan Ainsworth house, near Harrisville, Simpson County, ca. 1860-70.

Present owner: Miss Gertie Ainsworth

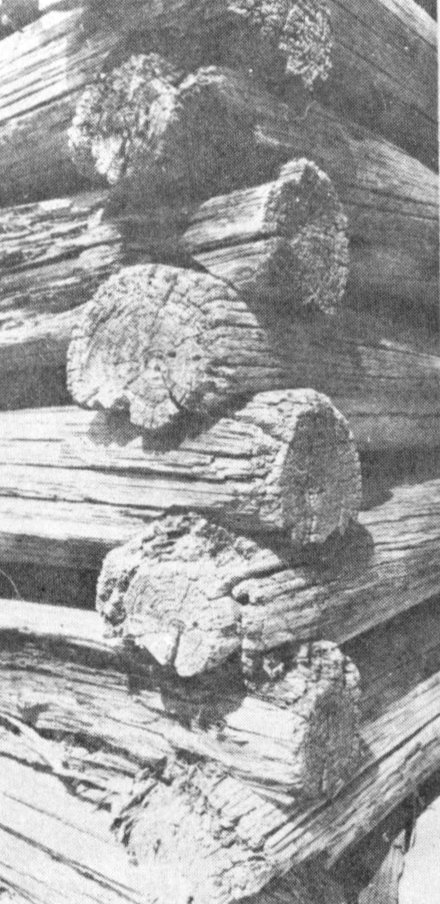

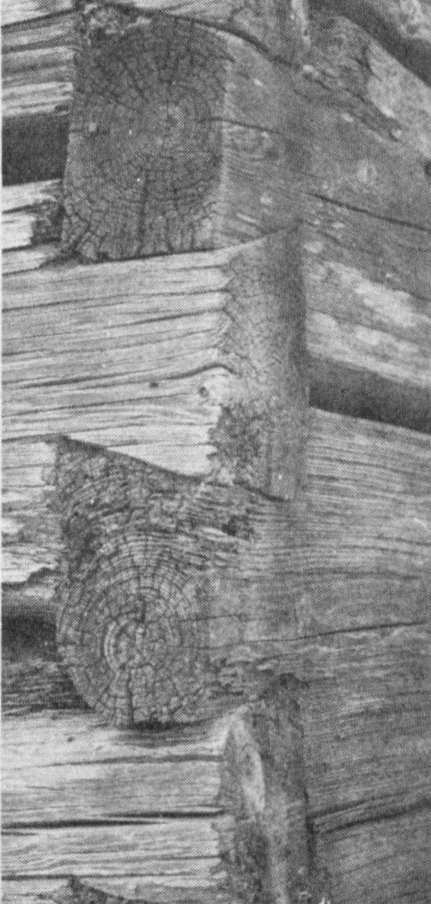

7. SADDLE NOTCH

Aunt Judy cabin, Wiggins,

Stone County, ca. 1870.

Present owner: B. C. Batson

8. V-NOTCH

Sullivan house, Smith County,

ca. 1810-20.

Present owner: Shep Sullivan

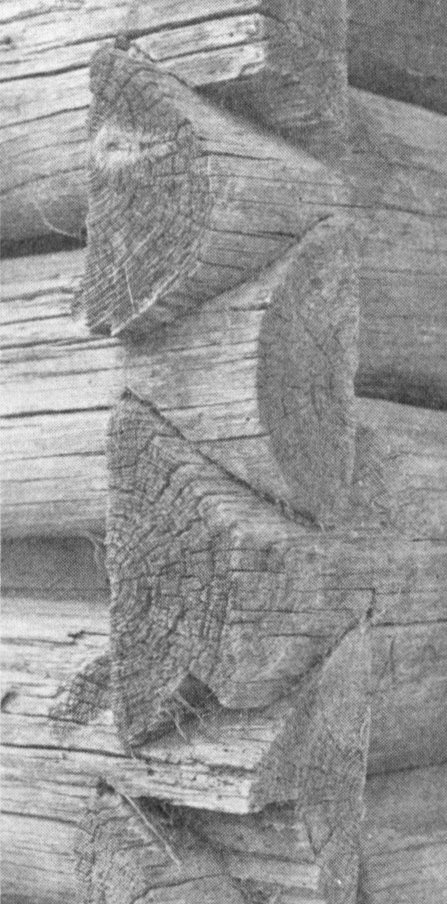

9. HALF-DOVETAIL NOTCH

Wiley McNeill house, Clarke

County, ca. 1820-30.

Present owner: Charles McGee

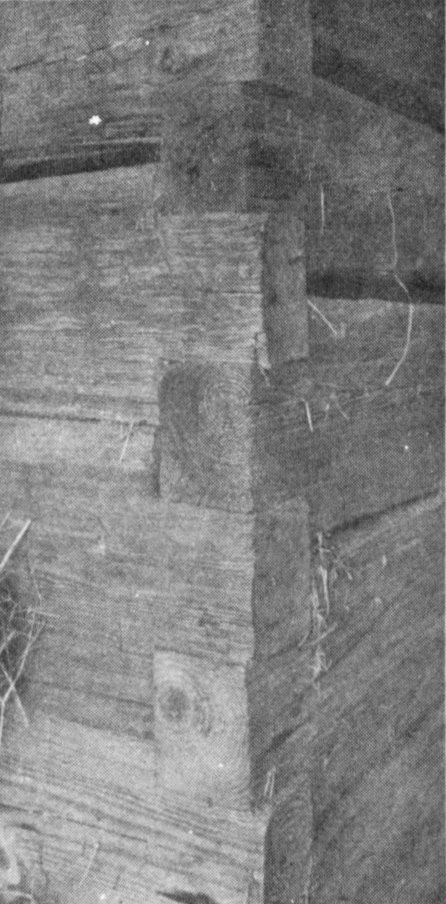

10. SQUARE NOTCH

Lang barn, near Shubuta,

Clarke County. Built over an

1815-1830 dogtrot.

Present owner: Mrs. Mildred

Wilkins

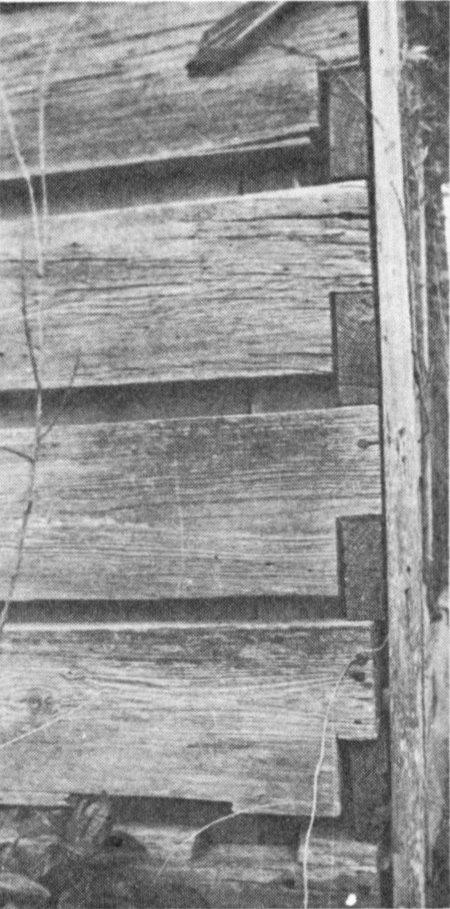

11. HALF-SQUARED

Strong River farm house,

Simpson County. Present

owner: Mrs. Guy Gillespie

12. SADDLE-V COMBINATION

Carter Place, George County,

pre-Civil War. Present owners:

Mr. and Mrs. Bill Bailey

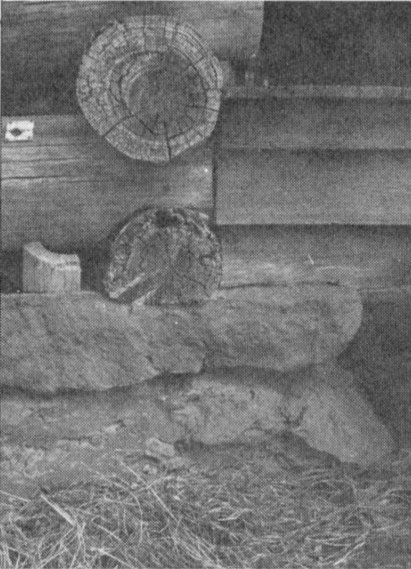

13. Heart pine section for foundation block. Wiley McNeill house, Clarke County, ca. 1820-30. Present owner: Charles McGee

14. Native sand rocks for foundation block. John A. McLeod house, Forest County, 1920. Present owner: Mrs. Lida Rogers

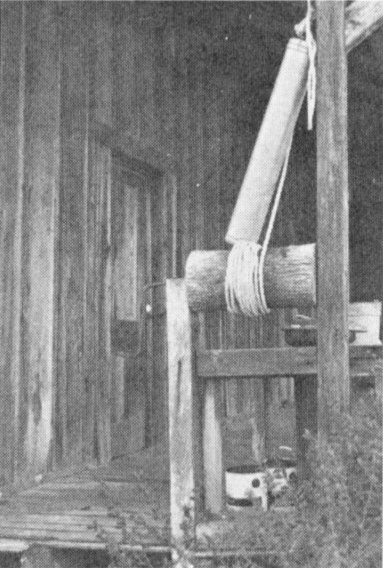

15. Porch well. Sam Hosey house, near Moss, Jasper County. Present owner: Ross Hosey

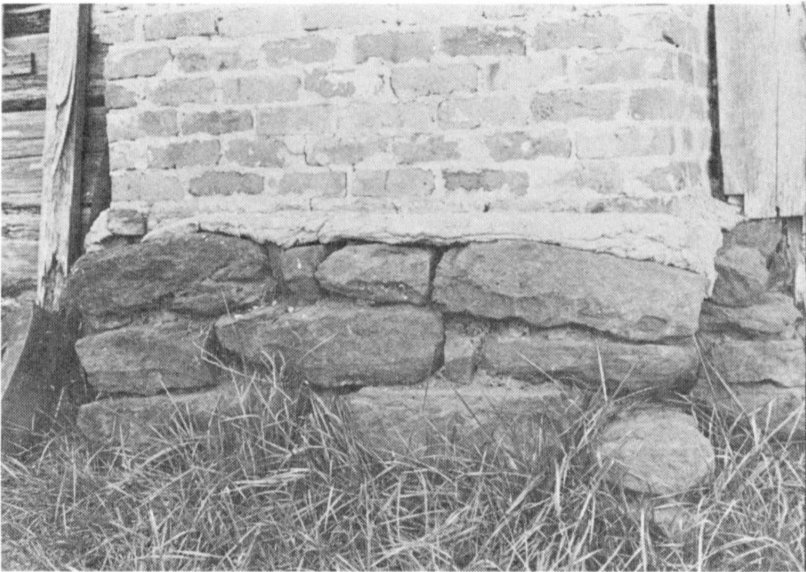

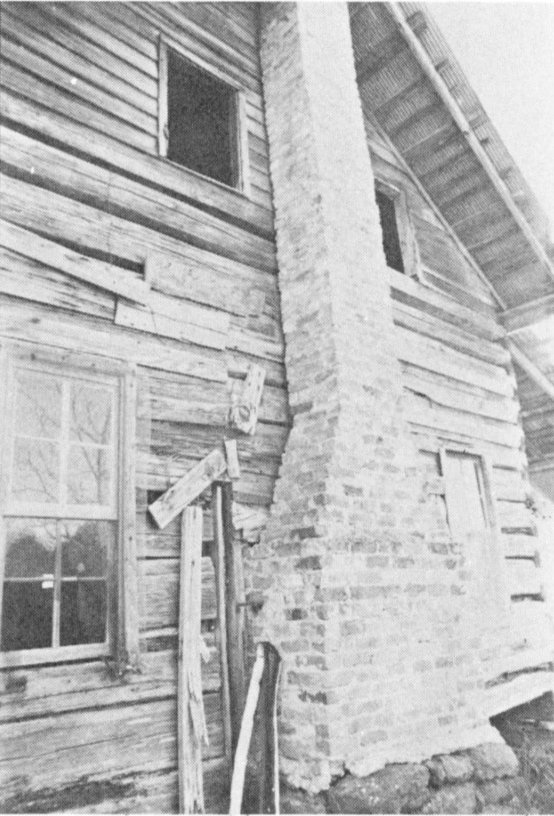

16. Bricks replaced mud-and-stick chimney in 1951. The original foundation stones remain. Wiley McNeill house, Clarke County.

17. Loft windows. Wiley McNeill house, Clarke County. ca. 1820-30.

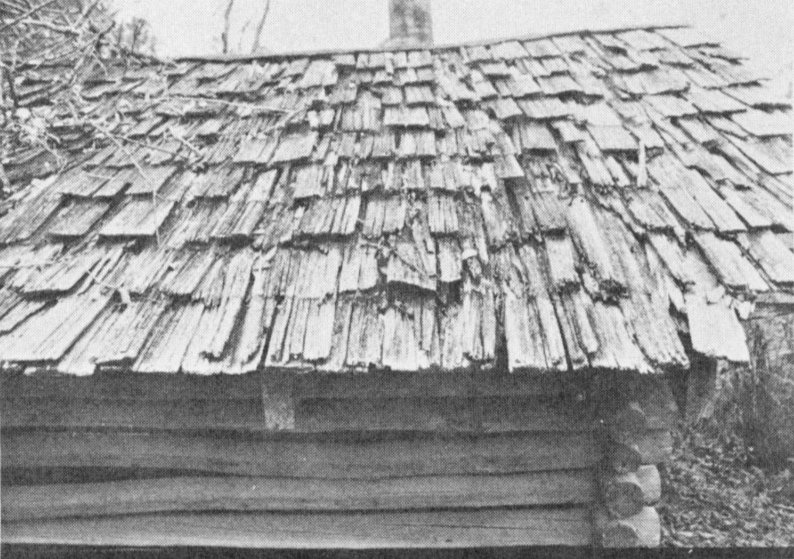

18. Shingle or board roof. Tool shed, Walthall County.

Present owner: George Wingo

19. Window shutter. John Walters cabin, Rankin County, 1860s.

Present owner: James Huff

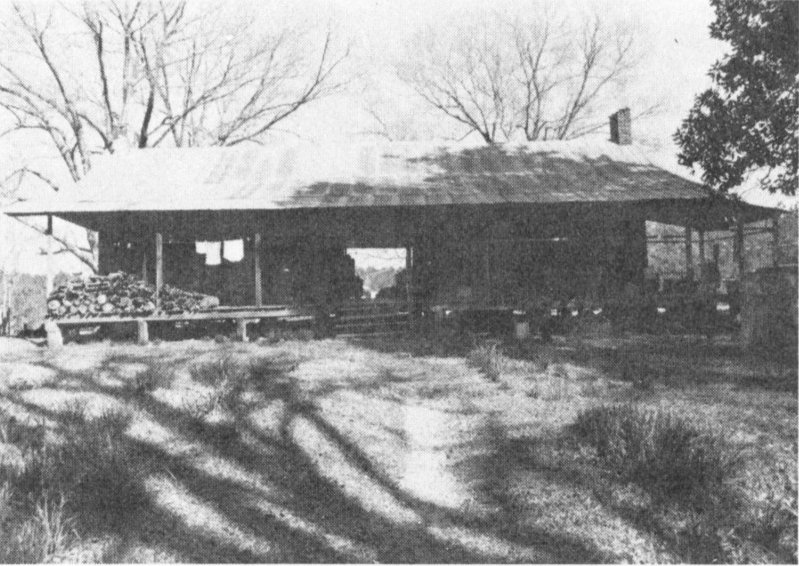

20. Detached kitchen. David Bracey Ward house, Silver Creek,

Lawrence County.

Present owner: Mrs. Alma Hedgepeth

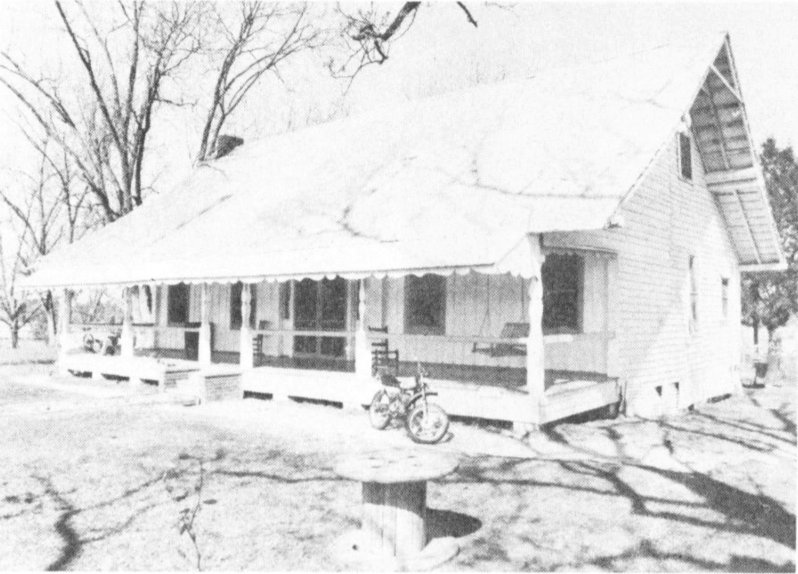

21. Jonathan Ainsworth house, near Harrisville, Simpson County,

ca. 1860-70.

Present owner: Miss Gertie Ainsworth

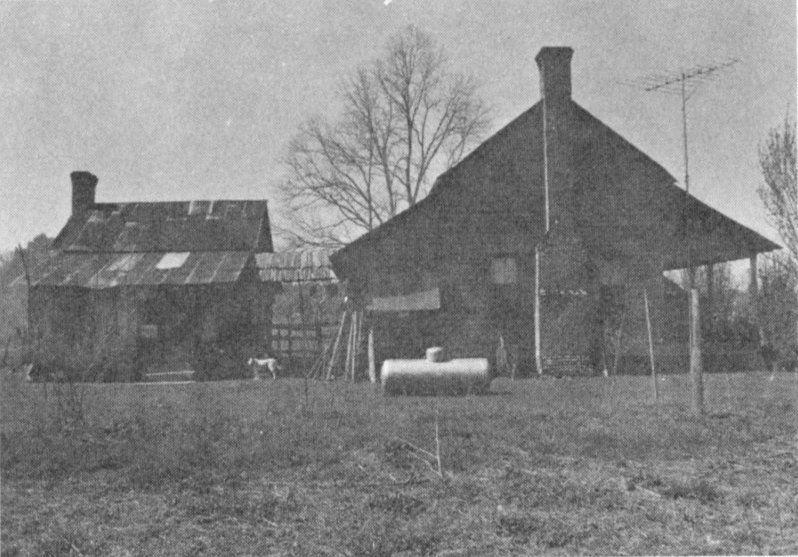

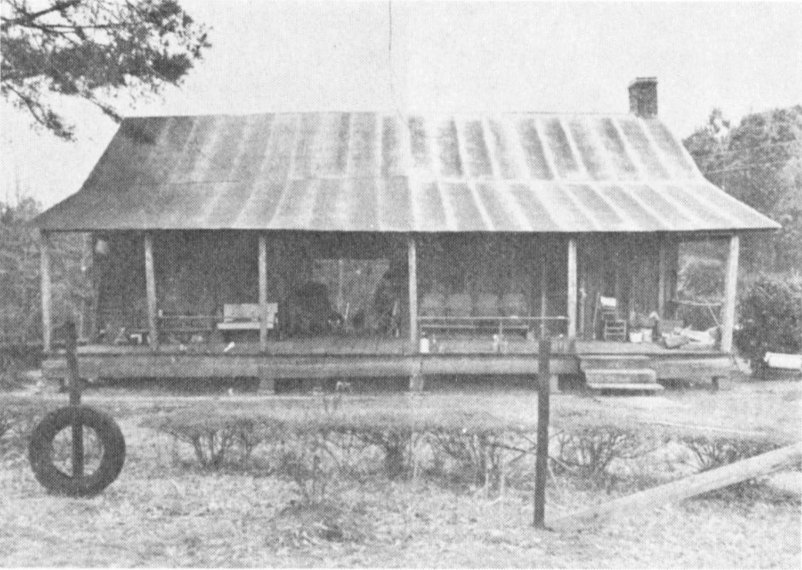

22. William Jackson Purvis house, Rankin County, pre-1880.

Present owner: Hulan Purvis

23. Hulan Purvis house, Rankin County, 1910.

Present owner: Hulan Purvis

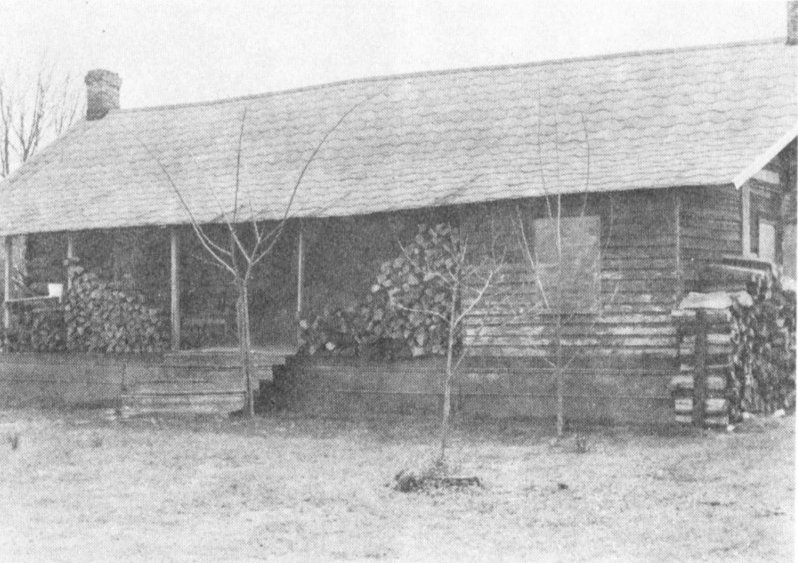

24. Sullivan house, near Mize, Smith County, 1810-20.

Present owner: Shep Sullivan

25. Press Bond house, Bond, Stone County, ca. 1870.

Present owner: Mrs. Mary Alice Coker

26. A non-dogtrot. Bob Goodloe house, Burns, Smith County.

Present owner: Bob Goodloe

27. Parker “tent” (1880), oldest cabin on Salem Church Campground, established in 1842.

28. Boykin Methodist Church, Smith County, 1858.

29. China Grove Methodist Church, Walthall County, 1854.

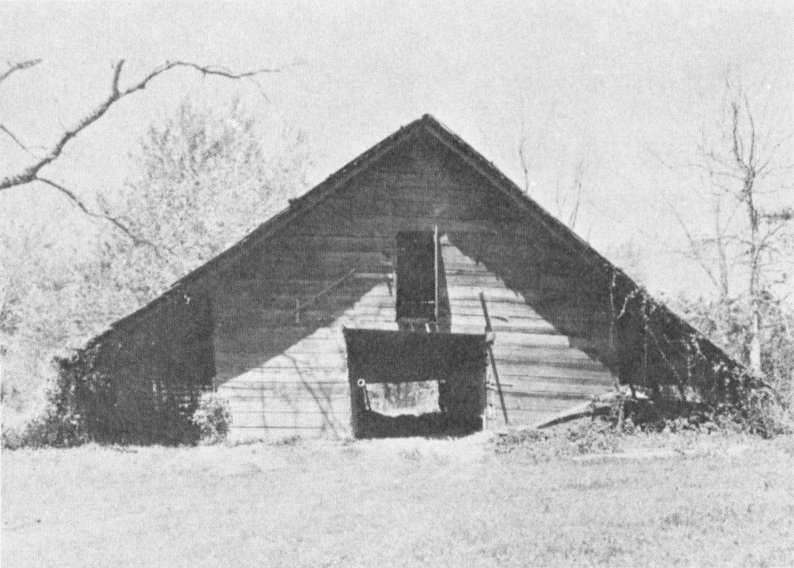

30. A-roof. Deen barn, Jefferson Davis County.

31. Lang barn, Clarke County. Built over an 1815-1830 dogtrot.

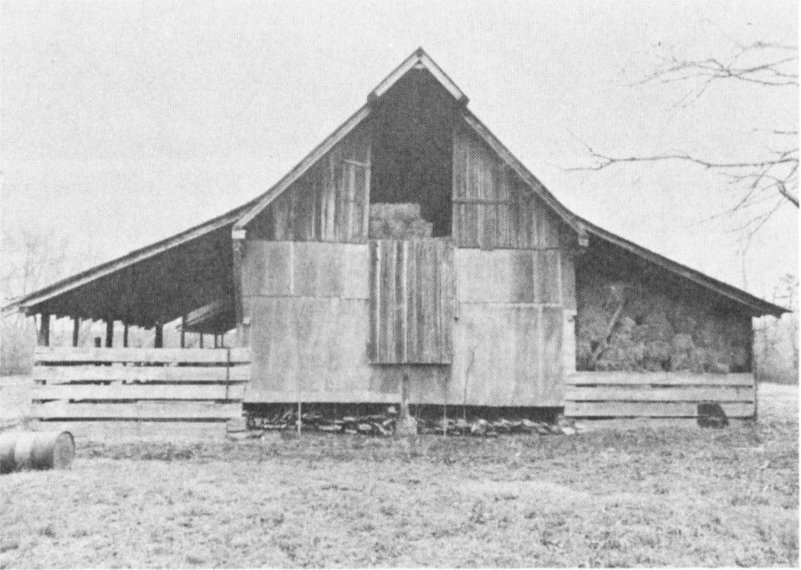

32. Log barn, Carter Place, George County.

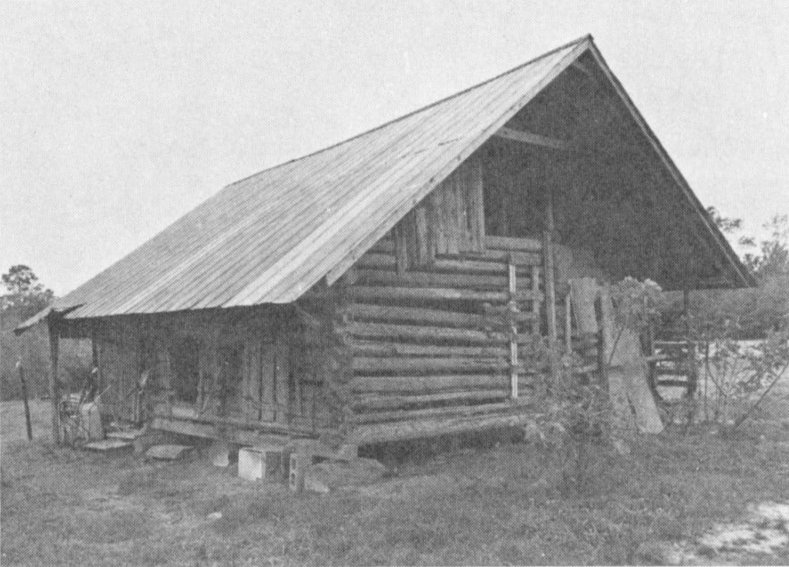

Present owner: Mr. and Mrs. Bill Bailey

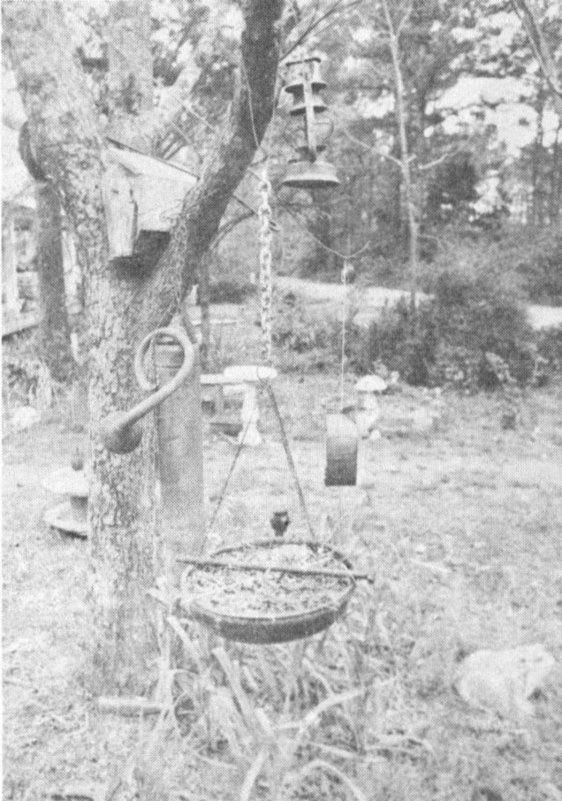

33. A decorative tree mobile

34. Bedsprings for a gate

35. Street light reflectors used as post covers to prevent rotting

36. 7-up sign used for backsplash

The log houses were built of peeled or “skunt” logs of native longleaf pine, called “lightered,” “yellow,” “heart” or “long-strawed” pine. The settler selected trees with straight smooth trunks approximately the same size. The trees were felled, cut into the correct length, and peeled. They were hauled to the building site with ox or mule teams. The foundation blocks were usually vertical sections of large heart pine logs (Fig. 13), although some houses used native iron rock as foundation stones (Fig. 14). These foundations held the sills of the house a foot or two off the ground so that the light and air under the house protected it from dampness and “wood lice” or termites. In some cases, the sills were laid directly on the earth. The sills of the Wiley McNeill house, Clarke County, laid on the ground around 1830, today show little sign of rotting or termite damage. The resin in heart pine acts as a natural preservative, making the wood almost indestructible.

Some of the houses were built with whole peeled logs (Fig. 4); others with split logs (Fig. 5) and still others with square-hewn logs (Fig. 6). The logs were notched or “scribed” at the corners to fit securely and steadily. The style of the notch varied with the cultural background, skill or preference of the builder. Saddle notching, V-notching, Half-dovetailing, Square cornering, Halved cornering and a saddle-V combination are found in the Piney Woods (Figs. 7-12). Of these, the half-dovetail is the most difficult to produce. It is self locking, as is the Saddle and V-notch, while the Square and Half-Square require the use of pegs to hold the timber in place.

The spaces between the logs were either chinked with clay and moss or battened with split pine pickets. The log houses left standing today in the Piney Woods are generally battened inside and out with pine boards. Exacting builders squared off the corners, but usually logs were left to extend beyond the notches. The floor joists rested on the sills and were fitted to make an even base for the floor of wide hand-planed pine boards. Many of the earlier houses had clay floors, but no house was found still retaining the dirt floor.

The ceiling, made of wide rough-hewn board, was attached to ceiling joists, providing a loft space in many of the houses. Small ladder-like stairs led through a hole in the ceiling to the loft, which was sometimes used for sleeping quarters or for storage of seeds, herbs, nuts, and gourds, (Fig. 17).

The rafters were made of small, peeled pine poles. Pine planks nailed to the rafters formed the base of the shingle roof. Straight grained pine trees were selected for roof shingles. The tree was cut into blocks eighteen to twenty inches long and split into “bolts.” A froe and maul were used to rive out the boards to a half-inch thickness and the roof was covered with the boards overlapping (Fig. 18). In the Piney Woods, such shingle roofs were called “board” roofs. Today most 18 have been replaced by tin or masonite. The overhang of the roof provided about eight feet front and rear for porches.

Each pen usually had a window on both sides of the fireplace, cut into the wall after the log pen was built. There were no window panels in the early houses, but thick shutters made of hand-planed pine boards (Fig. 19).

Each pen had a fireplace. The early chimneys were “catted,” made of “stick and mud,” and built on a foundation of native rocks, such as sand or iron rocks. The chimney was framed up with carefully laid pieces of oak strips. Prairie grass or sage was mixed with water and clay and thrown over each rung of the framing. The log grass overlapped each rung, filling the spaces. After the entire frame was covered, it was dressed down with mud. When the clay hardened, the chimney was ready for fire. Fireplaces were fitted with a bar and hooks to hold vessels for heating water and cooking. These inflammable stick-and-mud chimneys and fireplaces were replaced with bricks after kilns began operating (Fig. 16).

As a house grew, usually a kitchen was built behind and away from the house as a protection against fire. It was connected to the house by a board walkway either covered or uncovered (Fig. 20). It is rare today to find the detached kitchen still standing for most house owners, with access to electricity, tore down the kitchen wing and made a kitchen shed from a portion of the back porch. In the 20th century, outdoor toilets gave way to modern plumbing in shed rooms.

Before “running water” was available, it was considered a great convenience to have an additional well in the house. These wells were usually on a front porch and had a narrow cylinder for drawing water (Fig. 15).

The Ainsworth house in Simpson County, the Purvis house in Rankin County, and the Sullivan house in Smith County are well-preserved log dogtrots.

Jonathan Ainsworth built his log house on the Florence-Harrisville road in north Simpson County between 1860-1870 (Fig. 21). Gertie Ainsworth, present owner and granddaughter of Jonathan, was born in the house as was her father, Charles Houston Ainsworth.

Made of squared split-logs approximately 14 inches in diameter, the house was built in stages, following the typical pattern of progression. The 24-foot square north pen was constructed first with square notching. An identical pen was added a few years later, leaving a passageway between, with the whole house roofed over to provide a front and back porch. Soon afterwards, a kitchen and dining room, each about twelve feet square, were built off the rear of the house. In 1937, these structures were torn down and the north pen again became the kitchen and the south portion of the back porch was walled up as a bedroom. Later, with the arrival of electricity, the north back porch was walled up for a kitchen. None of the outbuildings are the original ones. The present corn crib was built in 1911; the “car 19 house” in 1925; the barn in 1935. Miss Ainsworth remembers fruit houses, which were built of small logs and daubed with mud. The house does not have plumbing and Miss Ainsworth still draws her water from the well conveniently placed on the front porch.

The Purvis house stands in the Walters Community in southeast Rankin County (Fig. 22). William Jackson Purvis began building the house prior to 1880. The fourth generation of his family now lives there.

Although both rooms have been ceiled and paneled in recent years and the south fireplace removed, the basic exterior remains unchanged.

The original pen was built on the east side of present-day Highway 43 and moved to the west side around 1882. The code for reassembling the pen can still be seen carved in the logs.

The north pen was added some twenty years later. The split-logs of pine are put together with V-notching. An unusual feature is a storm-pit built under the north pen with an entrance through an opening in the floor.

In 1905 when the first son married, the north portion of the front porch was walled off for the newly-weds. In the 1970s the north rear porch was walled off as a kitchen and the south rear porch as a bathroom. The house now has both electricity and plumbing.

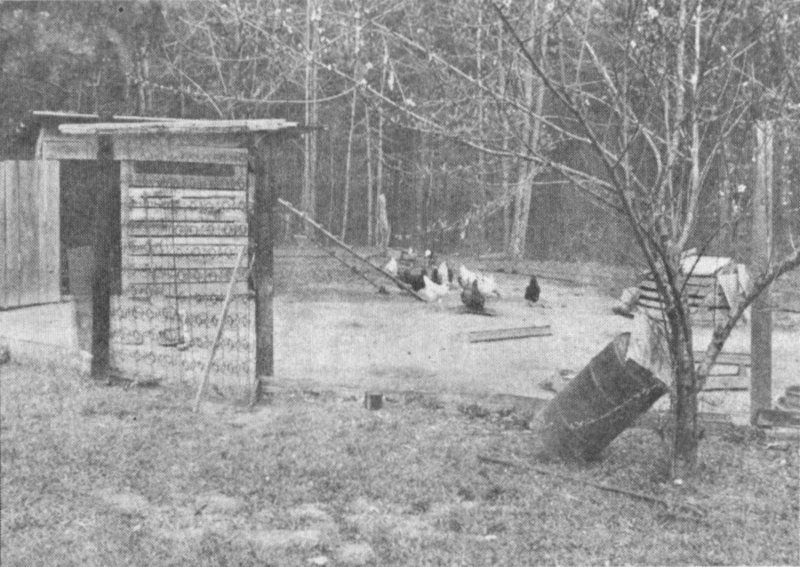

A functioning farm until recently, the out-buildings include a smoke house, cow barn, mule barn, blacksmith shop, seed house, chicken house, and tool shed. The blacksmith shop still contains the old bellows and a handmade grinding tool. The tool shed holds hand-carved mule hames, a hand-pegged rake, and other garden tools.

Tom Sullivan built his one-room cabin of square-hewn logs in Choctaw Indian country. The area later became known as Sullivan’s Hollow, Smith County. The original log cabin was built 1810-1820 when Sullivan migrated from Georgia, and his descendants have lived in it ever since.

A double-pen was added later using split logs instead of the original square-hewn. Three shed rooms have been added over the years, the last one for a bathroom in 1965 (Fig. 24).

Interior walls are battened with pine boards and the ceiling is made of “sawed” boards. The mud-and-stick chimneys on each end were replaced by brick chimneys in 1915. The dogtrot passageway is usually closed up in the winter months with plastic panels. The house is occupied today by Shep Sullivan, a sixth generation descendant of the builder.

Serving a special function were the campgrounds where Protestant religious meetings were held once or twice a year, usually during “laying-by” time. The early camp meetings were held in an arbor-like shelter constructed of oak posts with V-tops forming a frame for horizontal poles that were then covered with leafy branches. This shelter was called the tabernacle. Rough plank seats were constructed by laying long planks on supports held up by stakes driven in the ground. The dirt floor was covered with pine straw or sawdust to keep the dust down and the pulpit was made of rough planks. Smaller shelters called tents where the people camped out were built around the tabernacle and furnished with pine plank or pole beds and tables, straw and shuck mattresses. Later more substantial campgrounds, such as present-day Salem Church campground, were built with a permanent tabernacle and sturdy cabins. The Salem Campground on the Jackson-George County line is the oldest extant campground in the state (Fig. 27). The first camp meeting at Salem was held in 1826 and the present site was selected in 1842. The campground today is still arranged in the original U-shape, but the materials of the buildings have been replaced. The tabernacle is built of rough lumber, with three sides open and log posts supporting the roof. The floor, covered with pine straw, holds wooden benches which can seat 300 people. The cabins which surround the tabernacle are still traditionally known as “tents.” Each cabin has two rooms, one for sleeping, one for eating, cooking, or sitting, and the floors are covered with pine straw. A wooden bench adorns each front porch. The oldest tent on the campground is the Parker tent built around 1880. Meetings have been held every year at Salem Campground since 1826 except for two years during the Civil War.

After transportation improved and as the country became more thickly populated, churches were built. Rural Piney Woods churches were simple structures. Boykin Methodist Church (Fig. 28) near Burns and Piney Grove Church at Polkville are typical examples. The pioneer church building was rectangular, made of rough sawn pine, with pine shutters at the windows and home-made benches fronting toward the home-made pulpit. There was no ceiling, with the room rising to exposed hand-hewn rafters. Often there were two front doors, one for the men and one for the women, and one rear door. On the grounds of Piney Grove, one can still see the long stretch of tables which were built for “protracted meetings” which took the place of camp meetings. Instead of camping out, the people attended services during the day and went home for the night. There was always “dinner on the ground” at the protracted meeting.

Churches in more affluent areas generally had slave galleries, cabinet work on the pews, and glass windows. China Grove Methodist Church built in 1854 in Walthall County is a good example (Fig. 29).

Although roof styles vary, the barn type used almost exclusively in the Piney Woods is the transverse-crib barn. Henry Glassie, folk historian, has theorized that the transverse-crib barn developed in the southern Tennessee Valley. The Piney Woods settlers came from that area in large numbers. Roof styles include the gambrel and the pitched roof, but the most prevalent style is the A-roof (Figs. 30-32).

Each community usually had one farmer who built a water mill for grinding corn into meal. Lake Bounds in Clarke County has been the site of a grist mill since the beginning of the 19th century. The present mill was built by J. M. Martin in 1935 and is still operating.

Dr. William R. Ferris pointed out in Mississippi Folk Architecture, that “salvaged” items are common in folk structures.

Items discarded as “junk” in non-folk culture become functional or decorative in folk culture. A tour through the Piney Woods is a study in the art of recycling. Bed-springs become a garden gate. Prince Albert tobacco cans decorate a flower bed, rubber tires become planters, styrofoam egg cartons become tulips. Materials are imaginatively transformed into new uses (Figs. 33-36).

Folk architecture, defined as traditional structures built by craftsmen with no formal training in architecture, is disappearing. It came from and belonged to people whose lives were closely bound to the soil. Today technology is continuing to alter the cultural landscape and the mobile house trailer, the concrete-block structure, the prefabricated house are the new folk structures.