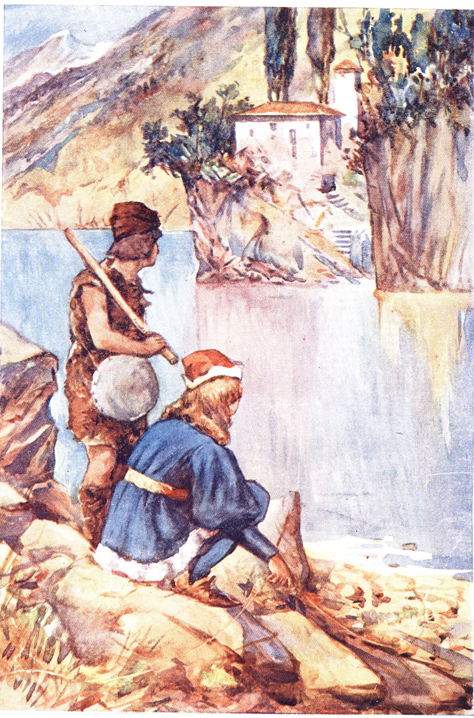

“Look yonder; that is the house of Darkeye the forester. We are safe!”

THOMAS NELSON AND SONS, Ltd.

LONDON, EDINBURGH, AND NEW YORK

| “Look yonder; that is the house of Darkeye the forester. We are safe!” | Frontispiece |

| “See that tall tower,” said Wolf | 16 |

| “Isn’t he a bonnie bit bairn?” | 96 |

| William never moved, though his great chest seemed to heave | 144 |

A STORY FOR THE YOUNG

Once upon a time, a boy lost his way in a vast forest that filled many a valley and passed over many a hill—a rolling sea of leaves for miles and miles, farther than the eye could reach. His name was Eric, son of the good King Magnus. He was dressed in a blue velvet dress, with a gold band round his waist, and his fair locks in silken curls waved from his beautiful head. He was a lovely boy, and if you looked into his large blue eyes, and saw his sweet smile, you would say in your heart, “There is a boy so winning and brave and true, that I would dearly like to have him as a friend and companion.” But, alas! his hands and face were scratched, and his clothes torn with the briars, as he ran here and there like one much perplexed. Sometimes he made his way through tangled brushwood, or crossed the little grassy plains in the forest, now losing himself in dark ravines, then climbing up their steep sides, or crossing with difficulty the streams that hurried through them. For a long time he kept his heart up, and always said to himself, “I shall find it, I shall find it;” until, as the day advanced, he was wearied and hungry; and every now and then he cried, “Oh, my father! where is my father? I’m lost! I’m lost!” And “Where, oh, where is my gold thread?”

All day the forest seemed to him to be very sad. He had never seen it so gloomy. There was a strange sadness in the rustle of the leaves, and a sadness in the noise of the streams. He did not hear the birds sing as they used to do. But he heard the ravens croak with their hoarse voice, as their black forms swept along the precipices which here and there rose above the forest, and he never saw so many large hawks wheeling in the sky. They always appeared to be wheeling over his head, pausing, and fluttering as if about to dart down upon him. But on he journeyed, in the hope of finding his way out of the boundless forest, or of meeting some one who would be his guide. At last the sun appeared to be near its setting, and he could see the high branches of the trees shining like gold, as its rays from the west fell upon them. But underneath, the forest was getting darker and darker, and all the birds were preparing to sleep, and everything at last became so still that he could hear his steps echoing through the wood, and if he stopped, he heard his heart beating, or a leaf falling; but nowhere did he see a house, and no human being had he met since morning. Then the wind suddenly began to rise, and he heard it at first creeping along the tree-tops like a gentle whisper, and by-and-by to call louder and louder for the storm to come. Dark clouds gathered over the sky, and rushed along chased by the winds, that were soon to search the forest and fight with the old trees. No wonder if the boy began to fear, in case some evil would happen to him. Not that he was a coward, but a very bravehearted boy; but he had done wrong, and it was that which made him afraid.

At last, wearied and hardly able to go further, he sat down at the root of an old oak, burying his face in his hands, not knowing what to do. He then tried to climb the tree, and there to sleep somewhere among its branches, in case wild beasts should attack him. But as he was climbing up, he heard some one singing with a loud voice. He listened attentively, and looking eagerly through the leaves, he saw a boy apparently older than himself, dressed in rough shaggy clothes, as if made from skins of wild animals. His long matted hair escaped over his cheeks from under a black bearskin cap. With a short thick stick he was driving a herd of swine through the wood. “Hey there, you black porker!” cried the boy, as he threw a stone at some pig which was running away. “Get along, you lazy long snout!” he shouted to another, as he came thump on its back with his short stick. And then he sang this song with a loud voice which made the woods ring:—

“Get along, you rascals,” cried the savage-looking herd, “or I’ll kill and roast you before your time;” and soon the herd, with his swine, were concealed from Eric’s sight by the wood; but he still heard his “rub-a-dub” chorus, to which he beat time with a sort of rude drum, which he had made for himself with a skin and hoop. Eric determined to make his acquaintance, or at all events to follow him to some house; so he descended from the tree, and ran off in the direction from which he heard the song coming. He soon overtook him.

“Hollo!” said the wild-looking lad, with as much astonishment as if Eric had fallen from the clouds. “Who? where from? where to?”

“I have lost my way in the wood,” said Eric, “and want you to guide me.”

“To Ralph?” asked the swineherd.

“Ralph! pray, who is he?”

“Master, chief, captain, all,” replied the young savage.

“I will go anywhere for shelter, as night is coming on; but I will reward you if you bring me to my father’s home.”

“Who is your father, my fine fellow?” inquired the swineherd, leaning on his stick.

“The king,” replied Eric.

“You lie! Ralph is king.”

“I speak the truth, swineherd.”

The swineherd by this time was examining Eric’s dress with an impudent look. “Pay me now,” said he; “give me this gold band, and I will guide you.”

“I cannot give you this gold band, for my father gave it to me, and I have lost enough to-day. By the bye, did you see a gold thread waving anywhere among the trees?”

“A gold thread! What do you mean? I saw nothing but pigs until I saw you, and I shall treat you like a pig, d’ye hear? and lick you too, for I have no time to put off. So give me your band. Come, be quick!” said he, with his fierce face, and holding up his stick as he came up to Eric.

“Keep off, swineherd; don’t touch me!”

“Don’t touch you! why shouldn’t I touch you? Do you see this stick? How would you like to have it among your fine curls, as I drive it among the pigs’ bristles?” and he began to flourish it over his head, and to press nearer and nearer. “Once! twice! when I say thrice, if you do not unbuckle, I shall save you the trouble, and leave you to the wild beasts, who would like a tender bit of prince’s flesh better than pork. Come; once! twice!”

Eric was on his guard, and said, “I shall fight you, you young robber, till death, rather than give you this band—so keep off.”

“Thrice!” shouted the herd, and down came his thick cudgel, which he intended should fall on Eric’s head.

But Eric sprang aside, and before he could recover himself, dashed in upon him, tripped him up, and threw him on the grass, getting on top of him and seizing him by the throat in a moment. The herd, in his efforts to get out of Eric’s grasp, let go his cudgel, which Eric seized and held over his head. “Unless you promise, master swineherd, to leave me alone, I may leave you alone with the wild beasts.”

“You are stronger than I thought,” said the herd. “Let me up, or I shall be choked. Let me up, I say, and I promise to guide you.”

“I shall trust you,” said Eric, “though you would not trust me. Rise!”

So the herd rose and picked up his cap, but Eric would not give him his stick until he guided him to some house. “Come along,” said he sulkily.

“What is your name?” asked Eric.

“They call me Wolf. I killed a wolf once with my boar-spear.”

“Why, Wolf, did you try to kill me?”

“Because I wanted your gold belt.”

“But it is a great sin to rob and kill.”

“Other people rob me, and would kill me too if I did not take care of their pigs,” said Wolf carelessly.

“You should fear God, Wolf.”

“I fear that name truly, for Ralph always swears by it when he is in a rage. But I do not know what it means.”

“O Wolf, surely your father and mother told you about God, who made all things, and made you and me; God, who loves us, and wishes us to love Him, and to do what is right?”

“I have no father or mother,” replied Wolf, “nor brothers or sisters, and I never heard of God. No one cares for me but my pigs, and so I sleep with them, and eat with them.”

“Poor fellow!” said Eric, with a look of kindness; “I am sorry for you. Here is all the money I have. Take it. I wish to show you that I have no ill will to you;” and Eric gave him a gold coin.

Wolf gave a grunt like one of his pigs, and began his song of “Rub-a-dub.”

“No one ever gave me money before,” remarked Wolf almost to himself, as he examined the coin on his rough hand, which looked like tanned leather. “How much is this?” inquired Wolf.

Eric explained its value. The herd was astonished, and began to think what he could purchase with it. He seemed very anxious to conceal it, and at last did so in the top of his hairy cap.

“See that tall tower,” said Wolf, “which looks like a rock above the trees; that is the only house near for twenty miles round. You can reach it soon; and when you do reach it,” said Wolf, speaking low, as if some one might hear him, “take my advice, and get away as fast as you can from my master Ralph, for”—and Wolf gave a number of winks, as much as to say, I know something.

“What do you mean?” asked Eric.

“Oh, nothing, nothing; but take Wolf’s advice, and say to Ralph you are a beggar. Put the gold band in your pocket, and swear to remain with him, but run off when you can. Cheat him; that’s my way.”

“It is not my way,” replied Eric, and, come what may, never will be, for a voice says to me,—

“Ha! ha!” said Wolf; “I wish you lived with Ralph. He would teach you another lesson, my lad.”

“I would rather that I had you, Wolf, to live in my house. I would be kind to you, and help you to be good, and tell you about God, who lives in the sky.”

“And is that He who is speaking? Listen!”

Thunder began to mutter in the sky.

“Yes, it is He,” replied Eric; “and if you listen, you will also hear Him often speak with a small still voice in your heart.”

“I never heard Him,” replied Wolf; “but I cannot stay longer with you, for my pigs will wander: there is a black rascal who always leads them astray. Now, king’s son, give Wolf the stick; it is all he has.”

“Here it is to you, and I am sure you will not use it wrongly; you will try to be good, Wolf? for it will make you happy.”

“Humph!” said Wolf, “I am happy when I get my pigs home, and Ralph does not strike me. But I must away, and see you don’t tell any one you gave me money. They would rob me.” And away he ran among the trees in search of his pigs, while Eric heard his little drum, and his song of “Rub-a-dub, halloo!” die away in the distance.

Another loud peal of thunder and flash of lightning made Eric start, and off he ran towards a light which now beamed from the tower. But he thought to himself, “I am much worse than that poor Wolf, for I knew what was right, and did not do it. I heard the voice, but did not attend to it. Oh, my father, why did I not obey you?”

Sometimes he lost sight of the light, and again he caught it, till it became brighter and brighter, and very soon he came to a high rock, on the top of which was perched a tall dark tower. After groping about, he found a narrow path that led up to the tower. From one of the windows of the tower the light was brightly shining. He went up a flight of steep steps till he reached a massive door covered with iron, and knocked as loud as he could, when a large dog began barking furiously inside, and springing up to the door, as if it would tear it down. Then a gruff voice called out of a window over the door, “Who is there? Who disturbs me in this way?”

The little boy replied, “Please, sir, I am Eric, son of King Magnus, and I have lost my way in this wood.”

“The son of the king, are you?” asked the voice. “That is a grand joke! Let me have a sight of you.” Then the window was shut, and he heard footsteps coming tramp, tramp down the stairs, and the voice said to the dog, “Lie down, hound, and don’t be greedy! You would not eat a young prince, would you? Lie down!”

The door was then opened by a fierce-looking man with a long beard. The man bid him enter, and examined him about himself and his journey. Eric answered truly every question.

Then the man rang a bell for an old woman who lived in the house, and bid her take the boy with her, and give him his supper. The old woman looked very ugly and very cross, and led Eric up, up, a great number of dark gloomy stairs, until she reached a small room, with a bed and table in it, where she bade Eric wait till she brought him supper.

The big hound followed them, and stayed in the room while the woman went away. Eric was at first afraid of the dog, he was so large and wild-looking; but he came and laid his head on his knee, and Eric scratched his ears, and patted him, and was very kind to him. The supper came, and little Eric managed to keep a few bits of meat out of his own supper for the dog, and when the old woman went out of the room he fed the hound, who seemed very hungry, and said to him, “Good dog, I love you very much.” The dog wagged his tail, and looked up kindly with his large eyes, for he was thankful for his supper, and ate much more than Eric.

“Now,” said the old woman gruffly, when she took away the remains of the supper, “you have ate what would do me for a week. You won’t starve, master prince. Go to bed.”

The old woman left him, but suddenly returning, she discovered Eric on his knees. As he rose she scoffed and jeered him, and asked, “Do you always say your prayers?”

“Yes, always,” replied the boy.

“Who taught you?”

“My mother, who is dead.”

The old woman heaved a deep sigh, but the boy did not know why. Perhaps she used to pray when she was a little girl herself, and had given up doing so, and become wicked; or perhaps she thought of some child of her own whom she had never taught to pray. She then went away without speaking a word more, and Eric was left in darkness. He looked out through the narrow window of his room, but could see nothing but black clouds rushing over the sky. Far down he heard a stream roaring, and the wind, which now blew a gale, came booming over the tree-tops, and howling round the tower. Every now and then a flash lighted up the forest, and the thunder crashed in the sky. It was a fearful night!

By-and-by Eric heard footsteps at his door, and immediately the man with the beard entered it, and sat down. “Do you know,” he asked, “where your father is?”

“No,” said Eric; “as I told you, I lost my way in the forest, and have been wandering all day, and cannot find him; but perhaps you will send some one to-morrow with me to show me the way to his castle, and I am sure my kind, good father will give you a rich reward.”

“You are very, very far from your father’s house,” said the man, “and I fear you will never see him again; but come with me, and I shall show you some beautiful things that will please you.” So the man took Eric by the hand, and, carrying a bright lamp in the other, led him into a room that seemed full of gold and silver, with beautiful dresses sparkling with diamonds, and every kind of splendour, and he said, “Stay with me, my boy, and I will give you all this, for I am a king too, and will make you my heir.”

“Oh no, no,” said Eric; “I will never forsake my own father.”

The man then said, “If you stay with me, you need never go to school all day, but may amuse yourself from morning till night, and have a beautiful pony to ride, and a gun to shoot deer with, and also fishing-rods, and a servant to attend you, and any kind of meat and drink you like best. Do stay with me!”

“You are very kind,” said Eric, “but I cannot be happy without my father. Oh, my dear father! if I found you I would never leave you more!”

“Come then with me, my fine fellow, and I shall show you something different,” said the man, seizing Eric firmly by the arm, and looking very fierce.

After walking along a passage, from the end of which confused noises came, a door was opened, and in a large hall, round a great oak table, sat a company of fierce-looking men, drinking from large flagons which stood before them. Their faces were red, and their eyes gleamed like fire. Ralph placed Eric on the table. One of the robbers was singing this song:—

No wonder poor Eric trembled as he heard that lawless band thus glorying in their shame, and like demons singing their horrid song in praise of all that was most dreadful and most wicked. He had read stories of robbers, which sometimes made him think that they were fine, brave fellows, but now that he was among them, he saw how depraved, cruel, and frightful they were. Their savage, coarse looks terrified him; but he was held by Ralph on the table.

When the song was ended, one of them asked, “Whom have we got here?”

“Who do you think?” replied Ralph. “What would you say, my men, to a young prince—no less than the son of our great enemy, King Magnus?”

“A young prince! The son of Magnus! What a prize!” they exclaimed. “What shall we do with him?”

“First of all, let us have his gold belt,” said Ralph, unbuckling Eric’s belt. “Ha! what a pretty thing it is!”

“My father gave it to me, and I don’t wish to part with it. The swineherd Wolf tried to take it from me, but I fought him, and kept it,” said Eric.

“Wolf is a brave young robber,” replied Ralph, “and he shall have it for his trouble. In the meantime, my lad, it is mine. But what, my men, shall we do with the prince?”

“Kill him,” said one.

“Starve him to death,” said another.

“Put his eyes out, and send him back to his father,” said a third.

Eric prayed to God, but said nothing.

“I propose,” said Ralph, “to make him a captain if he will stay with us.”

“Never!” said Eric; “I would rather die!”

“Let him die, then,” said a fierce robber; “for his father hung my brother for killing one of his nobles.”

“I tell you what we will do with the lion’s whelp,” said Ralph: “let us keep him in prison, and send a message to his father that we have him snug in a den among the mountains, and that, unless he sends us an immense ransom, we shall kill him.”

“That will do famously,” said the robbers; “so off with him!”

Then Ralph led the boy downstairs—down, down, until Eric thought they never would stop—and at last they came to an iron door, with great bars on it, and a large lock, and Ralph turned to Eric, and said, “I know your father, and I hate him! for he sends his soldiers after me, and tries to save travellers from me; and now I have got his son. I will keep you here till you die, or till he pays!” Then he opened the dungeon door, and thrust Eric in. When it closed it echoed like thunder through the passages. Eric lay down on the dungeon floor, and wept till his heart seemed to break.

All seemed a strange dream. Oh, how he repented having disobeyed his father! and how he seemed to be as bad as the dreadful robbers in having done what he pleased, and followed his own will, instead of doing what was right! After some time he heard some rustling, as if high up on the wall, and a voice whispering “Eric!”

“Who is there?” asked Eric, and his little heart trembled.

“Silence! quiet! it is Wolf. Here is a small window in your prison, and I have opened it outside; climb up, get out, and run for your life.”

Eric heard no more, but scrambled in the dark up the rough stones in the wall until he reached the window. As he looked out he saw the stars and the woods. He soon forced his way through, and dropped down on the opposite side. Some one caught him in his arms. It was Wolf.

“Here is your gold band, Eric. I got it from Ralph; for He who was speaking in the thunder has been saying things in my heart. You were kind to poor Wolf. Now run for your life! I shall close the window again. Ralph will never know how you got out, and he will not open the prison door till after breakfast. So you have a long time. Run as long as you can along that road till you reach a hill, then cross it and follow a stream. Run off!”

“Bless you, Wolf!” said Eric; “I shall never forget you.”

Poor Eric! how he ran, and ran, beneath the stars! He felt no fatigue for a time. He thought he heard the robbers after him; every time the wind blew loud, he imagined it was their wild cry. On he ran till he reached the hill, and crossed it, and came to a green spot beneath a rock, when he could run no more, but fell down, and whether he fainted or fell asleep he could not tell.

Eric knew not how long he slept, but as in a dream he heard a sweet voice singing these words:—

Eric opened his eyes, but moved not a limb, as if under some strange fascination. It was early morning. High overhead a lark was also “singing like an angel in the clouds.” The mysterious voice went on in the same beautiful and soothing strain,—

Eric could neither move nor speak; but in his heart he confessed with sorrow that he had done what was wrong. And again the voice sang,—

“I shall arise and go to my father!” said Eric, springing to his feet. He saw beside him a beautiful lady, who looked like a picture in his father’s room of his dead mother, or like one of those angels from heaven about whom he had often read.

And the lady said, “Fear not! I know you, Eric, and how it came to pass that you are here. Your father sent you for a wise and good purpose through the forest, and gave you hold of a gold thread to guide you, and told you never to let it go; but instead of doing your duty, and keeping hold of the thread, you let it go to chase butterflies and gather wild berries and to amuse yourself. This you did more than once. You neglected your father’s counsels and warnings, and so you lost your thread, and then you lost your way. What dangers and troubles have you thus got into through disobedience to your father’s commands, and want of confidence in his love and wisdom! But if you had only trusted your father’s directions, the gold thread would have brought you to his beautiful castle, where there is to be a happy meeting of your friends, with all your brothers and sisters.” Poor little Eric began to weep! “Listen to me, child,” said the lady kindly, “for you cannot have peace but by being good. Do you know, all your brothers and sisters made this very journey by help of the gold thread, and they are at home with great joy.”

“Oh, save me, save me!” cried Eric, and caught the lady’s hand.

“Yes, I shall save you,” said she, “if you will learn obedience. I know and love you, dear boy. I know and love your father, and have been sent by him to deliver you. I heard what you said, and know all you did, last night, and I was very glad that you proved your love to your father, and your love of truth, and your love of others, and this makes me hope all good of you for the future. Come now with me.”

And so the beautiful woman took him by the hand. The storm had passed away, and the sun was shining on the green leaves of the trees, and every drop of dew sparkled like a diamond. The birds were all warbling their morning hymns, and feeding their young ones in their nests. The streams were also dancing down the rocks and through the glens. “The mountains broke forth into singing, and all the trees clapped their hands with joy.” Everything thus seemed so happy to Eric, for he himself was happy at the thought of doing what was right, and of going home. The lady led him to a sunny glade in the wood, covered with wild flowers, from which the bees were busy gathering their honey, and she said, “Now, child, are you willing to do your father’s will?”

“Oh yes!”

“Will you do it, whatever dangers may await you?”

“Yes!”

“Well, then, I must tell you that your father has given me the gold thread you lost; and he bids me remind you that if you keep hold of it, and follow it wherever it leads, you are sure to come to him at sunset; but if you let it go, you may wander on in this dark forest till you die, or are again taken prisoner by robbers.”

“Oh, bless you,” said Eric, “for such good news! I am resolved to do my duty, come what may.”

“May you be helped to do it!” said the lady. She then gave him a cake, to support him in his journey. “And now, child,” she added, “one advice more I will give you, and it was given you by your father, though you forgot it; it is this—if ever you feel the thread slipping from your hands, or are yourself tempted to let it go, pray immediately, and you will get wisdom and strength to find it, to lay hold of it, and follow it. Before we part, kneel down and ask assistance to be good and obedient, brave and patient, until you meet your father.”

The little boy knelt down and repeated the Lord’s Prayer; and as he said, “Thy will be done on earth, as it is done in heaven,” he felt calm and happy as he used to do when he knelt at his mother’s knee, and he thought her hand was on his head, and that she kissed his cheek and blessed him. When he lifted up his head there was no one there but himself; but he saw an old gray cross, and a Gold Thread was tied to it, and passed away, away, shining through the woods.

With a firm hold of his gold thread, the boy began his journey home. He passed along pathways on which the brown leaves of last year’s growing were thickly strewn, and from among which flowers of every colour were springing. He crossed little brooks that ran like silver threads and tinkled like silver bells. He went under trees with huge trunks, and huge branches that swept down to the ground and waved far up in the blue sky. The birds hopped about him, and looked down upon him from among the green leaves, and they sang him songs, and some of them seemed to speak to him. He thought one large bird like a crow cried, “Good boy, good boy!” and another whistled, “Cheer up, cheer up!” and so he went merrily on, and very often he gave the robins and blackbirds that came near him bits of his cake.

After a while, he came to a green spot in the middle of the wood, without trees, and a footpath went direct across it, to the place where the gold thread was leading him, and there he saw a sight that made him wonder and pause. It was a bird about the size of a pigeon, with feathers like gold and a crown like silver, and it was slowly walking not far from him, and he saw gold eggs glittering in a nest among the grass a few yards off. Now he thought it would be such a nice thing to bring home a nest with gold eggs! The bird did not seem afraid of him, but stopped and looked at him with a calm blue eye, as if she said, “Surely you would not rob me?” He could not, however, reach the nest with his hand, and though he pulled and pulled the thread, it would not yield one inch, but seemed as stiff as a wire.

“I see the thread quite plain,” said the boy to himself, “the very place where it enters the dark wood on the other side. I will just jump to the nest, and in a moment I shall have the eggs in my pocket, and then spring back and catch the thread again. I cannot lose it here, with the sun shining; and, besides, I see it a long way before me.” So he took one step to seize the eggs; but he was in such haste that he fell and crushed the nest, breaking the eggs to pieces, and the little bird screamed and flew away; and then all at once the birds in the trees began to fly about, and a large owl flew out of a dark glade, and cried, “Whoo—whoo—whoo-oo-oo!” and a cloud came over the sun!

Eric’s heart beat quick, and he made a grasp at his gold thread, but it was not there! Another, and another grasp, but it was not there! and soon he saw it waving far above his head, like a gossamer thread in the breeze. You would have pitied him, while you could not have helped being angry with him for having been so silly and disobedient when thus tried, if you had only seen his pale face, as he looked above him for his thread, and about him for the road, but could see neither! And he became so confused with his fall, that he did not know which side of the open glade he had entered, nor to which point he was travelling. But at last he thought he heard a bird chirping, “Seek—seek—seek!” and another repeating, “Try again—try again—try—try!” and then he remembered what the lady had said to him, and he fell on his knees and told all his grief, and cried, “Oh, give me back my thread! and help me never, never, to let it go again!”

As he lifted up his eyes, he saw the thread come slowly, slowly down; and when it came near, he sprang to it and caught it, and he did not know whether to laugh, or cry, or sing, he was so thankful and happy! “Ah!” said he, “I hope I shall never forget this fall!” That part of the Lord’s Prayer came into his mind which says, “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.”

“Who would have thought,” said he to himself, “that I was in any danger in such a beautiful, green, sunny place as this!”

Then on he went, and a large crow on a tree was hoarsely croaking, “Beware, beware!”

“Thank you, Mr. Crow,” said the boy, “I shall;” and he threw him a bit of bread for his good advice, and ran on gaily to make up for lost time.

But now the thread led him through the strangest places. One was a very dark deep ravine, with a stream that roared and rushed far down, and overhead the rocks seemed to meet, and thick bushes concealed the light, and nothing could Eric see but the gold thread, that looked like a thread of fire, though even that grew dim sometimes, until he could only feel it in his hand. And whither he was going he knew not. At times he seemed to be on the edge of a precipice, until he almost thought the next step must lead him over and plunge him down; but just when he came to the very edge, the thread would lead him quite safely along it. Then appeared a rock which looked like a wall, and he would say to himself, “Well, I must be stopped here! I shall never be able to climb up!” But just as he touched it, he would find steps cut in it, and up, up, the thread would lead him to the top! Then it would bring him down, down, until he once stood beside a raging stream, and the water foamed and dashed. “And now,” he would think, “I must be drowned; but never mind, I will not let my thread go.” But so it was, that when he came so near the stream as to feel the spray upon his cheek, and thought he must leap in if he followed his thread, what would he see but a little bridge that passed from bank to bank, and by which he crossed in perfect safety; until he began to lose fear, and to believe more and more that he would always be in the right road, as long as he did not trust mere appearances, but kept hold of his thread!

At last Eric got very tired and hungry, for his cake was nearly done, and he had started early, and it was now well on in the day. But what was very strange, the thread supported him more than a staff could have done, and seemed to lift him up from the ground and make him go lightly along.

Eric had now to endure a great trial of his faith in the thread. As he journeyed on, the thread led him up a winding path towards the summit of a hill, descending which the large trees of the forest were left behind, and small stunted bushes grew among masses of gray rocks. The path was like the bed of a dry brook, and was often very steep. There were no birds, except little stonechats, that hopped and chirped among the large round stones. Far below, he could see the tops of the trees, and here and there a stream glittering under the sunbeams. Nothing disturbed the silence but the hoarse croak of the raven, or the wild cry of a kite or an eagle, that, like a speck, wheeled far up in the sky. But, suddenly, Eric heard a roar like thunder, that seemed to come from the direction towards which the thread was leading him. He stopped for a moment, but the thread was firm in his hand and led right up the hill. On he went, and no wonder he was afraid, when, as he turned the corner of a rock, he heard another roar, and saw the head of a large lion looking out of what seemed to be a cave, a few yards back from the edge of a dizzy precipice! He saw, too, that the path he must follow was between the lion’s den and the precipice! What now was to be done? Would he give up his thread and fly? No! A voice in his heart encouraged him to be brave and not fear, and he knew from his experience that he had always been led in safety and peace when he followed the road, holding fast to his thread. He was certain that his father never would deceive him, or bid him do anything but what was right; and he was sure, too, that the lady, from her love to him, and her teaching him to trust God and to pray, would not have bid him do anything that was wrong. And then an old verse his nurse taught him came into his mind,—

All this, and much more, passed through little Eric’s mind in a minute, and so he resolved to go on, come what might. There was just one thing he saw which cheered him, and that was a white hare, sitting with her ears cocked, quite close to the lion’s den, and he wondered how she had no fear, but could not explain it at the time. On he went, but he could hardly breathe, as the thread led still nearer and nearer the den. These big eyes were glaring on him, and seemed to draw him closer and closer! There the lion was, on one side of the path, and the great precipice on the other. One step more, and he was between them. He went on until he was so near that he seemed to feel the lion’s breath, when suddenly he sprang out on him, and tried to strike him with his huge paw that would have crushed him to the dust! Eric shut his eyes, and gave himself up for lost. But the lion suddenly fell back, for he was held fast by a great iron chain, and so Eric passed in safety!

Oh! how thankful he was! and how gladly he ran downhill, the lion roaring behind him in his den. Down he ran until all was quiet again. As he pursued his journey in the beautiful green woods, something told him his greatest trial was past. He felt very peaceful and strong. And now, as he reached some noble old beech-trees, the thread fell on the grass, and he took this as a sign that he should lie down too, and so he did, grateful for the rest. He ate some of his cake that tasted so nice, and drank from a clear spring beside him, and gathered wild strawberries which grew in abundance all round him, and thus had quite a feast. He then stretched himself on his back among soft moss, and looked up through the branches of the gigantic trees, and watched with delight the sunlight speckling the emerald green leaves and brown bark with touches of silver, and, far up, the deep blue sky with white clouds reposing on it, like snowy islands on a blue ocean; and he watched the squirrels with their bushy tails, as they ran up the trees, and jumped from branch to branch, and sported among the leaves, until he fell into a sort of pleasant day-dream, and felt so happy, he hardly knew why.

As he lay here, he thought he heard in his half-waking dream a little squirrel sing a song. Was it not his own heart, now so glad because doing what was right, which was singing? This was the song which he thought he heard:—

As Eric opened his eyes and looked up, he saw a little squirrel with its tail curling up its back, sitting on a branch looking down upon him; and then it playfully ran away with the tail waving after it. “Farewell, happy little fellow!” said Eric; “I must do my work now, and play like you afterwards;” for now the thread again became tight, and Eric, refreshed with his rest, and hearty for his journey, stepped out bravely. He saw, at some distance beyond an open glade in the forest, a rapid river towards which he was descending, when he thought he perceived something struggling in the stream, and then heard a loud cry or scream for help, as if from one drowning. He was almost tempted to run off to his assistance without his thread, but he felt thankful that the thread became tight again, and led in the very direction from whence he heard the cries coming. So off he ran as fast as he could, and as he came to the brink of a deep, dark pool in the river, he saw the head of a boy rising above the water, as the poor little fellow tried to keep himself afloat. Now he sank—again he rose—until he suddenly sank down and did not again appear. Eric laid hold of his thread with a firm hand and leaped in over head and ears, and then rose to the surface, and with his other hand swam to where the boy had disappeared. He soon caught him, and brought him with great difficulty to the surface, which he never could have done unless the thread had supported them both above the water.

“Eric!” cried the gasping boy, opening his eyes, almost covered by his long wet hair.

“Wolf, is it you?” It was indeed poor Wolf, who lay panting on the dry land, with his hairy clothes dripping with water, and himself hardly able to speak. “Oh, tell me, Wolf, what brought you here? I am so glad to have helped you!”

After a little time, when Wolf could speak, he told him in his own way, bit by bit, how Ralph had suspected him; and how the old woman had heard him speaking as she was looking out of an upper window; and how when Ralph asked the gold belt he could not give it; and how he was obliged himself to fly; and how he had been running for his life for hours. “Now let us fly,” said Wolf; “I am quite strong again. I fear that they are in pursuit of us.”

They both went on at a quick pace, Eric having shown Wolf the thread he had asked him about the day before, and explained to him how he must never part with it, come what might. “Oh, rub-a-dub, dub!” said Wolf, squeezing the water out of his hair, as he trotted along; “I am glad to be away. Ralph would have killed me like a pig. The voice told me to run after you.” So on they went as fast as they could, when suddenly Wolf stopped, and listening with anxious face he said, “Hark! did you hear anything?”

“No,” said Eric; “what was it?”

“Hush!—listen!—there again—I hear it!”

“I think I do hear something far off like a dog’s bark,” replied Eric. “Hark!”

So they both stopped and listened, and far away they heard a deep “Bow-wow-wow-wow-o-o-o-o-o” echoing through the forest.

“Let us run as fast as we can,” said the boy, in evident fear; “hear him—hear him!”

“Bow-wow-wow-o-o-o-o,” and the sound came nearer and nearer.

“What is it? why are you so afraid?” anxiously inquired Eric.

“Oh! that is Ralph’s bloodhound, Tuscar,” cried Wolf, “and he is following us. He won’t perhaps touch me, but you he may.” So Eric ran as fast as he could, but never let go the gold thread, which this time led up a steep hill, which they were obliged to scramble up. “Run, Eric!—quick—hide—up a tree—anywhere!”

“I cannot, I dare not,” said Eric; “whatever happens, I must hold fast my thread.”

But they heard the “Bow-wow-o-o-o” coming nearer and nearer, and as they looked back they saw an immense hound rush out of the wood, and as he came to the water he saw the boys on the opposite hill, and so he leaped into the stream, and in a few minutes would be near them. And now he came bellowing like a fierce bull up the hill, his tongue hanging out, and his nose smelling along the ground, following their footsteps.

“I shall run and meet him,” said Wolf, “and stop him if I can;” and down ran the swineherd, calling “Tuscar! Tuscar! good dog, Tuscar!”

But though Tuscar knew Wolf, he passed him, and ran up to Eric. As he reached Eric, who stood calm and firm, the bloodhound stopped panting, smelling his clothes all round, but, strange to say, wagging his huge tail, and then ran back the way he had come, as if he had made a mistake, and all his race was for nothing! It was the large hound Eric had fed! So his kindness was not lost even on the dog.

Eric and Wolf now pursued their journey with light and hopeful hearts, for they had got out of what was called the wild robber country, and he knew that he was drawing near home. The thread was stronger than ever, and every hour it helped more and more to support him. On the two went together, Wolf trotting along with his short stick, and sometimes snorting and blowing with fatigue like one of his own pigs. They conversed as best they could about all they had seen.

“Did you see big Thorold the lion?” asked Wolf.

“I did,” said Eric; “he is very awful, but he was chained.”

“Lucky for you,” said Wolf, “for Ralph hunts with him and kills travellers. He will obey none but Ralph. I heard him roaring. He is hungry. He once ate one of my pigs, and would have ate me if he had not first caught the porker. I escaped up a tree.”

And thus they talked, as they journeyed on through woods, and across green plains, and over low hills, until, as they were walking along, Wolf complained of hunger. Eric at once gave him what remained of his large cake; but it did not suffice to appease the appetite of the swineherd, who was, however, very grateful for what he got. To their delight they now saw a beautiful cottage not far from their path, and, as they approached it, an old woman with a pretty girl, who seemed to be her daughter, came out to meet them.

“Good-day, young gentleman!” said the old woman, with a kind smile and a courtesy; “you seem to be on your travels, and look wearied. Pray come into my cottage, and I shall refresh you.”

“What lucky fellows we are!” said Wolf.

“We are much obliged to you for your hospitality,” replied Eric. But alas! the thread drew him in an opposite direction; so turning to Wolf he said, “I cannot go in.”

“Come, my handsome young gentleman,” said the young woman, “and we shall make you so happy. You shall have such a dinner as will delight you, I am sure; and you may remain as long as you please, and I shall dance and sing to you; nor need you pay anything.” And she came forward smiling and dancing, offering her arm to Eric. “Surely you won’t be so ungallant as refuse me! you are so beautiful, and have such lovely hair and eyes, and I never saw such a belt as you wear: do come!”

“Come, my son,” said the old woman to Wolf, as she put her hand round his neck.

“With all my heart,” replied Wolf; “for, to tell the truth, I am wearied and hungry: such offers as yours one does not get every day.”

“I cannot go,” again said Eric. They could not see the thread, for to some it was invisible; but he saw it, and felt it like a wire passing away from the cottage. “Who are you, kind friends?” inquired Eric.

“Friends of the king and of his family. Honest subjects, good people,” said the old woman.

“Do you know Prince Eric?” asked Wolf.

“Right well!” replied the young woman. “He is a great friend of mine; a fine tall comely youth. He calls me his own little sweetheart.”

“It is false!” said Eric; “you do not know him. You should not lie.” But he did not tell her who he was, neither did Wolf, for Eric had made a sign to him to be silent. “I won’t enter your dwelling,” said Eric, “for my duty calls me away.”

They both gave a loud laugh, and said, “Hear him! Only hear a fine young fellow talking about duty! Pleasure, ease, and liberty are for the young. We only want to make you happy: come!”

“I shall go with you,” said Wolf; “do come, Eric.”

“Wolf, speak to me,” said Eric, whispering to the swineherd. “You know I cannot go, for my duty tells me to follow the thread. But now I see that this is the house of the wicked, for you heard how they lied; they neither knew the king nor his children; and they laugh, too, at duty. Be advised, Wolf, and follow me.”

Wolf hesitated, and looked displeased. “Only for an hour, Eric.”

“Not a minute, Wolf. If you trust them more than me, go; but I am sure you and I shall never meet again.”

“Then I will trust you, Eric,” said Wolf; “the voice in my heart tells me to do so.”

And so they both passed on. But the old woman and the girl began to abuse them, and call them all manner of evil names, and to laugh at them as silly fellows. The girl threw stones at them, which made Wolf turn round and flourish his stick over his head. At last they re-entered the cottage, the old woman shaking her fist, and calling out from the door, “I’ll soon send my friend Ralph after you!”

“Oh, ho! is that the way the wind blows?” exclaimed the swineherd, with a whistle; and, grasping Eric’s arm, said, “You were right, prince! I never suspected them. I see now they are bad.”

“I saw that before,” replied Eric, “and knew that no good would come to us from making their acquaintance.”

“Were they not cunning?”

“Yes; but probably, with all their smiles, flattery, and fair promises, they would have proved more cruel in the end than either Ralph or old Thorold.”

“What would they have done to us? Why did they meet us? Who are they, think you?”

“I don’t know, Wolf; it was enough for me that they lied, and did not wish us to do what was right.”

Not long after this strange adventure they reached a rising ground from which a magnificent view burst upon them. Below there was a large lake, surrounded by wooded hills, above which rose noble rocks fringed with stately pines, and higher ranges of mountains beyond, some of whose summits were covered with snow that glittered like purest alabaster in the azure blue of the sky. Eric gave a cry of joy; for he saw the house of one of his father’s foresters, where he had once been with his father. “Wolf! Wolf!” he exclaimed, “look yonder; that is the house of Darkeye the forester. We are safe!” and the thread was leading straight down in the very direction which they wished.

Darkeye’s house was built on a small green island in the lake. The island was like a little fort, for on every side the rocks descended like a wall. It could only be approached by a boat, which Darkeye kept on the island, and then by a narrow stair cut out of the rock. No robbers could thus get near it, and Darkeye was there to give shelter to travellers, and to help any of the poor who had to pass that way. The thread led down to the shore and the narrow ferry. They forgot their fatigue, and ran down till they reached the ferry. “Boat ahoy!” shouted Eric.

By-and-by two boys were seen running out of the cottage, and after looking cautiously at those who were calling for the boat, they rowed off, and soon were at the shore, where stood Eric with his gold belt, and Wolf in his rough skins. “Don’t you remember me?” asked Eric. The boys looked astonished as they recognized the young prince, and received him joyfully into their boat, he holding by the thread, which seemed to cross the ferry towards the cottage.

How many questions were mutually put and answered in a few minutes! They told him their father was at home; and how he had lately seen the king; and how the king was anxiously looking for Eric’s return; and how glad all on the island would be to see him. And the younger boy told him how they had a tame otter, that fished in the lake, and a fine golden eagle which they had got young in her nest, that lived on the island with them; and how their mother had got another baby since he had been there, and how happy they all were, and so on, until they arrived at the island. And there was old Darkeye himself waiting to receive them; and when he saw who was in the boat, he ran down the stone steps and grasped the young prince’s hand, and drew him to his heart. “Welcome, welcome!” said he; “I knew you had been in the forest, but your father would not tell me anything more about you. He only said that he longed for your coming home. But who is this?” asked Darkeye, pointing to Wolf.

“A friend of mine,” said Eric, with a smile.

“My name is Wolf,” grunted the swineherd.

“I think I have seen him before. But no! What? Yes!” said Darkeye, examining him; then added, as if he had discovered some old acquaintance, “Surely I have seen him. Tell me, my fine fellow, did you——”

It was evident Darkeye had seen Wolf killing his game, or in some affray with the robbers. Wolf looked steadily at Darkeye, then at Eric, but said nothing.

“O Darkeye, do not trouble poor Wolf, but let him go into the cottage, and come you with me, as I wish to tell you all that has happened to me during these few days.”

So, while the boys took Wolf to the cottage, and food was being prepared, Eric told Darkeye all his adventures; and you would have been sure that the forester was hearing something which surprised and interested him wonderfully, had you seen his face, and how he sometimes laughed, or knit his brows and looked angry, or sad and solemn, or sprang to his feet from the rock on which he was sitting beside Eric.

When Eric came to speak about the old woman and her daughter, “Ah!” said Darkeye, “there are not worse people in that wicked country! They say that the old woman is a witch of some kind. But whether she poisons travellers or drowns them, I know not. No doubt she is in league with Ralph the robber, and would have robbed you or kept you fast in some way or other till you were handed over to him. You were right, my prince, in all you did. The only way of being delivered from temptation is to be brave, and do what is right, come what may.” At last, grasping Eric by the hand, he led him back to the cottage. There Darkeye’s wife received him like a mother, and all the children gathered round him in surprise and admiration, he looked so brave and lovely.

One of the walls of the cottage was reared on the edge of the rock, so that it seemed a continuation of it, and to rise up from the deep waters of the lake. The boys were thus able often to fish with a long line out of the window. A winding stair led to a look-out on the roof, from which the whole island, called “The Green Island of the Lake,” could be seen. It was about a mile or more in circumference, and was dotted all over with the cottages of the other foresters and king’s huntsmen, each surrounded with clumps of trees, through which the curling smoke from the chimneys might be seen ascending. There were everywhere beautifully kept gardens, with fruits, and flowers, and beehives; and fields, too, with their crops. On the green knolls and in the little valleys might be seen cows and sheep; while flocks of goats browsed among ivy-covered rocks.

In the middle of the island was a little shallow lake, beside which the otter had his house among the rocks; and there the eagle also lived. All the children in the island were the best of friends, and they played together, and sailed their boats on the little lake, and every day met in the house of one of the foresters to learn their lessons; and on Sunday, as they were very far away from any church, old Darkeye used to read good books to them, and worship with them, and did all he could to make them good and happy. They often met at such times in the open air, beneath a large tree which sheltered them from the sun.

There was also in the island a house where, by the king’s orders, all poor travellers could find refuge and refreshment. And it was a great pleasure to the boys and girls to visit them; and if they were sick and confined to bed, to read to them, and attend to their wants. If the stranger had any children, the young islanders always shared their sports with them. And nothing pleased these stranger children more than to get leave to sail a boat, or to have the loan of a fishing-rod, or to hear the boys call Oscar—for that was the name of the otter—out of his den, and play with Tor the eagle; or to see them feed Oscar with some of the fish they had caught, and Tor with a bit of meat. The dogs were so friendly, too, that they never touched Oscar, but would swim about in the same pool with him. And so all were happy in the Green Island; because Darkeye had taught them what a wicked thing selfishness was, and that the only way to be happy was by thinking about others as well as themselves, and by loving one another. He also used to say: “Now, when you work, work like men, and when you play, play like boys: be hearty at both.” And so while there was no idleness, there was abundance of recreation.

Another evil was never permitted in the island, and that was disobedience to parents, or want of respect to the old. But, indeed, punishment for these offences was seldom or never needed. The young learned to like to do what was right, and were too brave and manly to give pain and trouble to others.

I should have mentioned, also, that they had a little band of musicians. One beat the drum, a few played the fife, and others some simple instrument; while almost all could sing tolerably well in parts. Thus, many a traveller would pause and listen with delight as he heard on a summer’s evening the chorus song from many voices, or the music from the band coming from the island. “Young people,” Darkeye used to say, “have much wealth and happiness given them, if they only used their gifts.”

But I am forgetting Eric and Wolf. They were both, you may be sure, ready for their dinner, and there was laid for them on a table, cream, cakes, and fresh trout, and such other good things as the kind woman could get ready.

But now the thread began to move, as if it wished Eric to move also. Before rising to depart, he told Wolf how Darkeye, for his sake, would be so glad to take care of him, until he got his father’s permission to bring him into the castle; that he would learn to be a huntsman, and be taught what was good, and to know about the voice that spoke in his heart, and that all the boys in the island would make him their friend if he did what was right.

“Ralph will come here!” said Wolf, hanging his head.

“I wish the rascal did,” said Darkeye, “for he would never go back. But he cannot enter my fort, and knows me and my huntsmen too well ever to try it. I have had more than one brush with the villain, and we hope soon to drive him and his brood from their bloody nest. Wolf, you are welcome and safe, for Eric’s sake!” Then turning to Eric, he said, “I shall teach him, and make a man of him, my young prince, depend upon it. And now, before we part, I have to ask a favour,” continued Darkeye. “You know our custom near evening? If the thread permits, remain and be one of us.”

“I remember it,” said Eric, “and will remain and be one of you, and let poor Wolf also be one.”

And so they entered the cottage, and all sat down round an open window which looked out upon the beautiful lake dotted with wooded islands, and surrounded by the noble forest, above which rose the giant peaks and precipices. The water was calm as glass, and reflected every brilliant colour from rock and tree, and, most of all, from the golden clouds, which already began to gather in the west. Darkeye read from the Blessed Book of one who had left his father’s house, and went to a far country, where he would fain have satisfied his hunger from the husks which the swine did eat, but who at last returned home after having suffered from his disobedience. When he closed the Book, all stood up and sang these words with sweet and happy voices:—

Then they knelt down, and Darkeye spoke to God in the name of them all, thanking Him for His goodness, and telling Him their wants. When they rose from their knees, the gold thread shone brilliantly, and, like a beam of light, passed out at the door in the direction of the ferry. During the singing of the verses, Wolf seemed for the first time quite overcome. He bent his head, and covered his face with his hands. He then said, in a low voice, when the short service was over, and as if speaking to himself, while all were silent listening to him, “I had a dream. Long, long ago. A carriage—a lady. She was on her knees crying. She had hold of me. Ralph was there and the robbers. I forget the rest.” He rose and looked out of the window, gazing vacantly.

“What can he mean?” asked Eric aside to Darkeye, who was looking tenderly on Wolf.

“Ah! who knows, poor boy! Singing always touches the heart of these wanderers. Perhaps—yes—it may be,” he said, so that Eric alone could hear him, “that he has been taken when a child by Ralph from some rich traveller, and perhaps his mother was killed! He may have been the child of good people. Was that his mother who prayed for him? If so, her prayers are now answered, for her boy will be delivered—poor Wolf!—Wolf, my boy,” said Darkeye, “come and bid farewell to your friend.”

Wolf started as from a dream, and came to Eric.

“Farewell, my kind Wolf, and I hope some day to see you in my father’s house.” The swineherd spoke not a word, but wiped his eyes with the back of his rough hand. “Cheer up, Wolf, for you will be good and happy here.”

“Wolf is happy already, and he will take care of the pigs, or do anything for you all.” He then held out his stick to Eric, and said, “Take it; it is all Wolf has: Ralph has the gold coin.”

“Thank you, good Wolf; but you will require it, and I need nothing to remember you.”

“Don’t be angry, Eric, for what I did in the forest when we met. My heart is sorry.”

“We did not know one another then, Wolf, and I shall never forget that to you I owe my escape.”

“Wolf loves you, and every one here.”

“I am sure you do, Wolf, and I love you. God bless you, Wolf, I must go; farewell!”

And so they parted. But all gathered round Eric, and accompanied him to the boat, blessing the little prince, and wishing him a peaceful and happy journey. Eric thanked them with many smiles and tender words. Darkeye alone went with him into the boat, wondering greatly at the thread, and most of all at the prince, who shone with a beauty that seemed not of this world. The prince landed, but Darkeye knew for many reasons that he could not accompany him in his journey, which he must take alone. Eric landed on the shore, embraced Darkeye, and waving his hand to all on the island, he soon was lost to their sight in the great forest.

A winding pathway, over the ridge of hills, led down to a broad and rapid but smooth river, and on its banks was a royal boat, beautiful to look upon. The thread led into the boat, and though no one was there, Eric entered, and sat on a velvet cushion on which the golden thread laid itself down. No sooner had he gone on board of the boat, than—as if his little foot, when it touched her, had sent her from the shore—she slowly moved into the centre of the channel, and was carried downwards by the current. On she swept on the bosom of that clear stream, between shores adorned with all that could delight the eye—rocks and trees and flowers, with here and there waterfalls, white as snow, from mountain rivulets which poured themselves into the great river. The woods were full of song, and birds with splendid plumage gleamed and flashed amidst the foliage like rainbow hues amidst the clouds.

Eric knew not whither he was being carried, but his heart was sunshine and peace. On and on he swept with the winding stream, until at last darting under a dark archway of brick, and then emerging into light, the boat grounded on a shore of pure white sand, while the thread rose and led him to the land.

No sooner had he stepped on shore and ascended the green bank, than he found himself at the end of a long, broad avenue of splendid old trees, whose tops met in a green arch overhead. The far-off end of the avenue was closed by a great stair of pure white marble steps which ascended to a magnificent castle. Wall rose above wall, and tower over tower. He saw grand flights of stairs, leading from one stately terrace to another, with marble statues, clear gushing fountains, and flower gardens, and every kind of lovely tree. It was his father’s castle at last! He ran on with breathless anxiety and joy. He soon reached it. A large gate was before him, that seemed to be covered with glittering gold. The thread led directly to it. As he reached the door, he saw the thread tied to a golden knocker, shaped like the old cross in the forest. Inscribed over the door were the words, “He that persevereth to the end shall be saved.” And on the knocker, “Knock, and it shall be opened.” He seized the knocker, and the moment it fell, the thread broke and vanished. A crash of music was heard inside. The door opened, and there stood Eric’s father, surrounded by his brothers and sisters; and the beautiful lady was there too, and many, many more to welcome Eric. His father clasped him to his heart, and said, “My son was lost, but is found!”

While all crowded around Eric with his weary feet and torn dress, kept together by his golden band, a chorus was heard singing,—

Then there rose a swell of many young voices singing,—

And then the sun set, and the earth was dark, but the palace of the king shone like an aurora in the wintry sky.

“And a little child shall lead them.”

“Wee Davie” was the only child of William Thorburn, blacksmith. The child had reached the age in which he could venture, with prudence and reflection, on a journey from one chair to another, his wits kept alive by maternal warnings of “Tak’ care, Davie; mind the fire, Davie.” And when his journey was ended in safety, and he looked over his shoulder with a cry of joy to his mother, he was rewarded, in addition to the rewards of his own brave and adventurous spirit, by such a smile as equalled only his own, and by the well-merited approval of “Weel done, Davie!”

Davie was the most powerful and influential member of the household. Neither the British fleet, nor the French army, nor the Armstrong gun, nor the British Constitution had the power of doing what Davie did. They might as well have tried to make a primrose grow or a lark sing! He was, for example, a wonderful stimulus to labour. His father, the smith, had been rather disposed to idleness before his son’s arrival. He did not take to his work on cold mornings as he might have done, and was apt to neglect many opportunities which offered themselves of bettering his condition; and Jeanie was easily put off by some plausible objection when she urged her husband to make an additional honest penny to keep the house. But “the bairn” became a new motive to exertion; and the thought of leaving him and Jeanie more comfortable, in case sickness laid the smith aside, or death took him away, became like a new sinew to his powerful arm, as he wielded the hammer, and made it ring the music of hearty work on the sounding anvil. The meaning of benefit-clubs, sick-societies, and penny-banks was fully explained by “wee Davie.”

Davie also exercised a remarkable influence on his father’s political views and social habits. The smith had been fond of debates on political questions, and no more sonorous growl of discontent than his could be heard against the powers that be, the injustice done to the masses, and the misery which was occasioned by class legislation. He had also made up his mind not to be happy or contented, but only to endure life as a necessity laid upon him, until the required reforms in Church and State, at home and abroad, had been attained.

But his wife, without uttering a syllable on matters which she did not pretend even to understand, and by a series of acts out of Parliament, by reforms in household arrangements, by introducing good bills to her own House of Commons, and by a charter, whose points were chiefly very commonplace ones, such as a comfortable meal, a tidy home, a clean fireside, a polished grate, above all, a cheerful countenance and womanly love—these radical changes had made her husband wonderfully fond of his own house. He was, under this teaching, getting every day too contented for a patriot, and too happy for a man in such an ill-governed world. His old companions could not at last coax him out at night. He was lost as a member of one of the most philosophical clubs in the neighbourhood. His old pluck, they said, was gone. The wife, it was alleged by the patriotic bachelors, had “cowed” him, and driven all the spirit out of him. But “wee Davie” completed this revolution.

One failing of William’s had hitherto resisted Jeanie’s silent influence. The smith had formed the habit, before he was married, of meeting a few companions, “just in a friendly way,” on pay-nights at a public-house. It was true that he was never “what might be called a drunkard,” “never lost a day’s work,” “never was the worse of liquor,” etc. But, nevertheless, when he entered the snuggery in Peter Wilson’s whisky shop, with the blazing fire and comfortable atmosphere; and when, with half a dozen talkative and, to him, pleasant fellows and old companions, he sat round the fire, and the glass circulated, and the gossip of the week was discussed, and racy stories were told, and one or two songs sung, linked together by memories of old merry meetings; and current jokes were repeated, with humour, of the tyrannical influence which some would presume to exercise on “innocent social enjoyment”—then would the smith’s brawny chest expand, and his face beam, and his feelings become malleable, and his sixpences begin to melt, and flow out in generous sympathy into Peter Wilson’s fozy hand, and there counted beneath his sodden eyes. And so it was that the smith’s wages were always minus Peter’s gains.

His wife had her fears—her horrid anticipations—but did not like to “even” her husband to anything so dreadful as what she in her heart dreaded. She took her own way, however, to win him to the house and to good, and gently insinuated wishes rather than expressed them. The smith, no doubt, was only “merry,” and never was ill-tempered or unkind; “yet at times—” “and then, what if—” Yes, Jeanie, you are right! The demon sneaks into the house by degrees, and at first may be dispelled, and the door shut upon him; but let him only once take possession, then he will keep it, and shut the door against everything pure, and lovely, and of good report, and bar it against thee and “wee Davie,” ay, and against better than thee and than all else, and fill the house with sin and shame, with misery and despair! But “wee Davie,” with his arm of might, drove the demon out.

It happened thus. One evening when the smith returned home so that “you would know it on him,” his child toddled to him, and, lifting him up, he made him stand before him on his knee. The child began to play with the locks of the Samson, and to pat him on the cheek, and to repeat with glee the name of “dad-a.” The smith gazed at him intently, and with a peculiar look of love, mingled with sadness.

“Isn’t he a bonnie bit bairn?” asked Jeanie, as she looked over her husband’s shoulder at the child, nodding and smiling to him.

The smith spoke not a word, but gazed still upon his boy, while some sudden emotion was strongly working in his countenance. “It’s done!” he at last said, as he put his child down.

“What’s wrang? what’s wrang?” exclaimed his wife, as she stood before him, and put her hands round his shoulders, bending down until her face was close to his.

“Everything is wrang, Jeanie!”

“Willie, what is’t? are ye no’ weel?—tell me what’s wrang wi’ you?—oh, tell me!” she exclaimed in evident alarm.

“It’s a’ richt noo!” he said, rising up, and seizing his child, lifted him up to his breast, and kissed him. He then folded him in his arms, clasped him to his heart, and looking up in silence, said, “Davie has done it, along wi’ you, Jeanie. Thank God, I am a free man!”

His wife felt awed, she knew not how.

“Sit doon,” he said, as he took out his handkerchief and wiped away a tear from his eye, “and I’ll tell you a’ aboot it.”

Jeanie sat on a stool at his feet, with Davie on her knee.

Her husband seized his child’s little hand with one of his own, and with the other took his wife’s. “I havena been what ye may ca’ a drunkard,” he said, “but I hae been often as I shouldna hae been, and as, wi’ God’s help, I never, never will be again!”

“Oh!” exclaimed Jeanie.

“Let me speak,” said William. “To think, Jeanie”—here he struggled as if something was choking him—“to think that for whisky I might beggar you and wee Davie; tak’ the claes aff your back; drive ye to the workhouse; break your heart; and ruin my bonnie bairn, that loves me sae weel, in saul and body, for time and for eternity! God forgie me! I canna stand the thocht o’t, let alane the reality!” and the strong man rose, and little accustomed as he was to show his feelings, he kissed his wife and child. “It’s done, it’s done!” he said; “dinna greet, Jeanie. Thank God for you and Davie, my best blessings.”

“Except Himsel’!” said Jeanie, as she hung on her husband’s neck.

“Amen!” said the smith; “and noo, woman, nae mair aboot it; it’s done. Gie wee Davie a piece, and get the supper ready.”

“Wee Davie” was also a great promoter of social intercourse, an unconscious link between man and man, and a great practical “unionist.” He healed breaches, reconciled differences, and was a peace-maker between kinsfolk and neighbours. For example: Jeanie’s parents were rather opposed to her marriage with the smith; some said because they belonged to the rural aristocracy of country farmers. They regretted, therefore, the day—though their regret was expressed only to old friends—when the lame condition of some of the horses had brought Thorburn into communion with their stable, and ultimately with their house. Thorburn was admitted to be a sensible, well-to-do man; but then he was, at best, but a smith, and Jeanie was good-looking, and “by ordinary,” with expectations of some “tocher,” and as her mother remarked, “though I say it, that shouldna say it,” etc., and so, with this introduction, she would proceed to enlarge on Jeanie’s excellences, commenting on the poor smith rather with pauses of silence, and expressions of hope “that she might be mistaken,” all of which, from their very mystery, were more depreciatory than any direct charges. But when “wee Davie” was born, the old couple deemed it proper and due to themselves—not to speak of the respect due to their daughter, whom they sincerely loved—to come and visit her. Her mother had been with her, indeed, at an earlier period; and the house was so clean, and Thorburn so intelligent, and the child pronounced to be so like old David Armstrong, Jeanie’s father, especially about the forehead, that the two families, as the smith remarked, were evidently being welded, so that a few more gentle hammerings would make them one.

“Wee Davie,” as he grew up, became the fire of love which heated the hearts of good metal so as to enable favourable circumstances to give the necessary finishing stroke which would permanently unite them. These circumstances were constantly occurring until, at last, Armstrong called on every market-day to see his daughter and grandson, and he played with the boy (who was his only grandson), and took him on his knee, and put a “sweetie” into his mouth, and evidently felt as if he himself was reproduced and lived in the boy. This led to closer intercourse, until David Armstrong admitted that William Thorburn was one of the most sensible men he knew, and that he would not only back him against any of his acquaintances for a knowledge of a good horse, but for wonderful information as to the state of the country generally, especially of the landed interest and the high rent of land. Mrs. Armstrong finally admitted that Jeanie was not so far mistaken in her choice of a husband. The good woman always assumed that the sagacity of the family was derived from her side of the house. But whatever doubts still lingered in their minds as to the marriage, these were all dissipated by one look of “wee Davie.” “I’m just real proud aboot that braw bairn o’ Jeanie’s,” she used to say to her husband. She added one day, with a chuckling laugh and smile, “D’ye no’ think yersel’, gudeman, that wee Davie has a look o’ auld Davie?”

“Maybe, maybe,” replied auld Davie; “but I aye think he’s our ain bairn we lost thirty years syne.”

“That has been in my ain mind,” said his wife; “but I never liked to say it. But he’s no’ the waur o’ being like baith.”

Again: There lived in the same common passage, and opposite to William Thorburn’s door, an old soldier, a pensioner. He was a bachelor, and by no means disposed to hold much intercourse with his neighbours. The noise of the children was obnoxious to him. He maintained that “an hour’s drill every day would alone make them tolerable. Obedience to authority; right about, march! That’s the thing,” the Corporal would say to some father of a numerous family in the “close,” as he flourished his stick with a smile rather than a growl. Jeanie pronounced him to be “a selfish body.” Thorburn had more than once tried to cultivate acquaintance with him, as they were constantly brought into outward contact. But the Corporal was a Tory, and more than suspected the smith of holding “Radical” sentiments. To defend things as they were was a point of honour with the pensioner—a religion. Any dislike to the Government seemed a slight upon the army, and therefore upon himself. Thorburn at last avoided him, and pronounced him proud and ignorant. But one day “wee Davie” found his way into his house, and putting his hands on his knees as he smoked his pipe at the fireside, looked up to his face. The old soldier was arrested by the beauty of the child, and took him on his knee. To his surprise, Davie did not scream; and when his mother soon followed in search of her boy, and made many apologies for his “impudence,” as she called it, the Corporal maintained that he was a jewel, a perfect gentleman, and dubbed him “the Captain.”

Next day, tapping at Thorburn’s door, the Corporal gracefully presented a toy in the shape of a small sword and drum for his young hero. That night he smoked his pipe at the smith’s fireside, and told such stories of his battles as fired the smith’s enthusiasm, called forth his praises, and, what was more substantial, a most comfortable tea by Jeanie, which clinched their friendly intercourse. He and “the Captain” became constant associates, and many a loud laugh might be heard from the Corporal’s room as he played with the boy, and educated his genius. “He makes me young again, does the Captain!” remarked the Corporal to his mother.

Mrs. Fergusson, another neighbour, was also drawn into the same net by “wee Davie.” She was a fussy, gossiping woman, noisy and disagreeable. She found Jeanie uncongenial, who “kept herself to herself,” instead of giving away some of her good self to her neighbour, and thus taking some of her neighbour’s bad self out of her. But her youngest child became seriously ill, and Jeanie thought, “If Davie was ill I would like a neighbour to speir for him,” and so she went upstairs to visit Mrs. Fergusson, and begged pardon, but “wished to know how Mary was?” and Mrs. Fergusson was bowed down with sorrow, and thanked her, and bid her “to come ben.” And Jeanie did so, and spoke kindly to the child, and told her, moreover, what pleasure it would give her to nurse her baby occasionally; and she invited the younger children to come down to her house and play with “wee Davie,” and thus keep the sick one quiet; and she helped also to cook some nutritive drinks, and got nice milk from her father for the sick one, and often excused herself for apparent meddling by saying, “When one has a bairn o’ their ain, they canna but feel for other folk’s bairns.”

Mrs. Fergusson’s heart became subdued, softened, and friendly, and she said, “We took it as extraordinar’ kind in Mrs. Thorburn to do as she has done. It is a blessing to have sic a neighbour.”

But it was “wee Davie” did it.

The street in which the smith lived was as uninteresting as any could be. A description of its outs and ins would have made a “social science” meeting shudder. Beauty or even neatness it had not. Every “close” or “entry” in it looked like a sepulchre. The back courts were a huddled confusion of outhouses; strings of linens drying; stray dogs searching for food; pigeons similarly employed with more apparent success and satisfaction; and cats creeping about; with crowds of children, laughing, shouting, and muddy to the eyes, acting with intense glee the great dramas of life, marriages, battles, deaths, and burials, with castle-building and extensive farming and commercial operations. But everywhere smoke, mud, wet, and an utterly uncomfortable look. And so long as we in Scotland have a western ocean to afford an unlimited supply of water, and western mountains to condense it as it passes in the blue air over their summits, and western winds to waft it to our cities, and so long as it will pour down, and be welcomed by smoke above and earth below—then consequently so long we shall find it difficult to be “neat and tidy about the doors,” or to transport the cleanliness of England into our streets and lanes. But, in spite of all this, how many cheerful homes, with bright fires and nice furniture, and rows of books, and intelligent, sober, happy men and women, with healthy, nice children, are everywhere to be found in those very streets, that seem to the eye of those who have never penetrated farther than their outside, to be “dreadful-looking places;” and who imagine that all their inhabitants must be like pigs in pigstyes, steeped in wretchedness and whisky; and infer that every ignorant and filthy and drunken Irish brawler and labourer is a fair type of the whole of our artisans.

There is, I begin to suspect, a vast deal of exaggerated nonsense written about the working classes. Be that as it may, I feel pretty certain of this, that there is no country on earth in which the skilled and well-conducted artisan can get so much for his money, socially, physically, intellectually, and morally, as in our own Britain, and none in which there are to be found so many artisans who take advantage of these benefits. But for the ignorant and ill-disposed, the idle and the drunken, there is no country where their degradation is more rapid, and their ruin more sure. The former can easily rise above the mud, and breathe a free and happy atmosphere; but if he falls into it, it is likely he will be sooner smothered and buried than anywhere else on earth.

A happier home could hardly be found than William Thorburn’s, smith, as he sat, after coming home from his work, at the fireside, reading his newspaper, or some book of weightier literature, Jeanie sewing opposite to him, and, as it often happened, both absorbed occasionally in the rays of that bright light, “wee Davie,” which filled their dwelling, and the whole world, to their eyes; or listened to the grand concert of his happy voice, which mingled with their busy work and silent thoughts, giving harmony to all. How much was done for his sake! He was the most sensible, efficient, and thoroughly philosophical missionary of social science in all its departments who could enter that house.