| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/talesofoldseapor00munro |

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of Part I, II and III.

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ⅓ ¼ etc; other fractions are shown in the form a/b, for example 21/95.

Display of Lat./Long. coordinates has been made consistent, with no space between the values, but with a space before N/S/E/W if present, for example 12°34′56″ N.

Changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

A GENERAL SKETCH OF THE HISTORY OF BRISTOL, RHODE ISLAND, INCLUDING, INCIDENTALLY, AN ACCOUNT OF THE VOYAGES OF THE NORSEMEN, SO FAR AS THEY MAY HAVE BEEN CONNECTED WITH NARRAGANSETT BAY: AND PERSONAL NARRATIVES OF SOME NOTABLE VOYAGES ACCOMPLISHED BY SAILORS FROM THE MOUNT HOPE LANDS

BY

WILFRED HAROLD MUNRO

OF BROWN UNIVERSITY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON

LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

1917

Copyright, 1917, by

Princeton University Press

Published November, 1917

Printed in the United States of America

| PAGE | |

| Introduction: Old Bristol | 1 |

| Part I—Simeon Potter and the Prince Charles of Lorraine | |

| 1—Simeon Potter | 37 |

| 2—Letter of Father Fauque | 48 |

| Part II—Norwest John and the Voyage of the Juno | |

| 1—Norwest John | 97 |

| 2—Voyage of the Juno | 100 |

| Part III—James de Wolf and the Privateer Yankee | |

| 1—James De Wolf | 205 |

| 2—Journal of the Yankee | 225 |

| Index | 289 |

[Pg 1]

TALES OF AN OLD SEA PORT

From the earliest days of the Plymouth Colony the name Mount Hope Lands has been applied to the peninsula in Narragansett Bay of which Bristol, Rhode Island, is the chief town. The history of this town is more crowded with notable incident than that of any other in New England. First and most picturesque is the story of the Norsemen. Around Mount Hope the legends of the Norsemen cluster, shadowy, vague, elusive, and yet altogether fascinating. Only legends they are and must remain.

After the lapse of a thousand years of changing climates and of varying shores no man can definitely locate the Vinland of the Vikings. Many have attempted to do so, and, like the late Professor E. N. Horsford,[1] have established their theses to their own satisfaction and the satisfaction of the present dwellers in their Vinland, but they have not succeeded in convincing any one else. One of the latest writers[2] approaching the subject without local prejudice, and judging of the past by the ever changing present, will have it that the physical conditions of the lands around Narragansett Bay in the eleventh century were such as to[2] make it more than probable that the “Hop” of the Norsemen is the Mount Hope of today.[3] In his conclusions all good Bristolians, yea more, all good Rhode Islanders, cheerfully join. Scandinavian writers insist that the name “Mount Hope” is of Norse origin. They assert that it is only an English spelling of the Indian name Montop, or Monthaup, and they are probably correct in their assertion. The Indians had no written language and our Pilgrim ancestors spelled the Indian words as they pleased, sometimes in half a dozen ways upon the same page. They go on to say that the termination “hop” was the name which Thorfinn and his companions gave to this region when they wintered here in 1008, and they bring forward the old Norse sagas to prove it. This is the story as the sagas tell it:

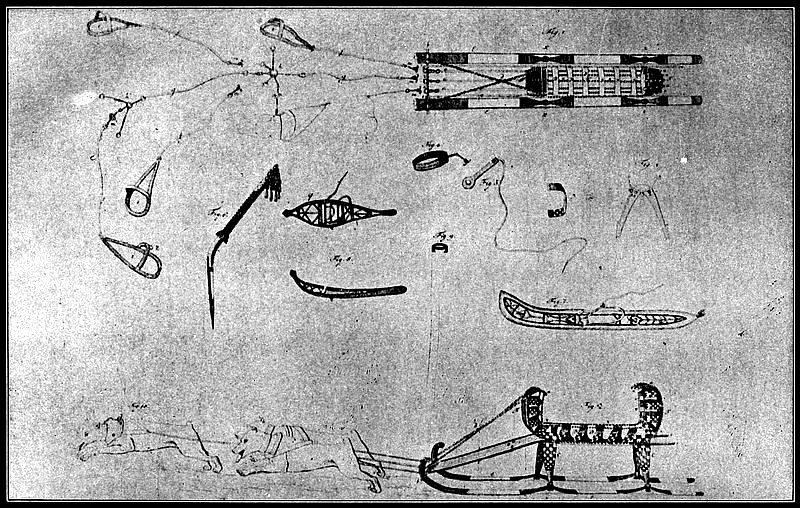

In the year of Our Lord 1000 the Norsemen first visited the shores of Vinland. They came from Greenland, a hundred years and more after their countrymen had discovered and colonized Iceland. Their ship was an open boat from fifty to seventy-five feet long, similar to the one dug from the sands at Sandefjord, Norway, in 1880, which is preserved in the museum of the university at Christiania. It was propelled by oars and had a short mast amidships on which was spread a small square sail. Both mast and sail were used only when the wind was fair. They came creeping along from headland to headland, seldom venturing out of sight of land in the unfamiliar seas. The mariner’s compass was then unknown, except perhaps to the Chinese, and the art of propelling a boat against the wind by “tacking” had not been developed, unless possibly by those same[3] Chinese. It would have been impossible to tack in one of the Viking ships. In the first place the sail area was too small and in the second place the steering was all done from one side. A long steering oar was fastened upon a fulcrum about two feet long on the right side of the boat, the steer-board, starboard side. On one tack the oar would have been useless because submerged, on the other equally useless because it could not go deep enough to “grip” the water. To men accustomed to the icy Arctic seas, voyages southward held out no terrors; they were only pleasant summer excursions.

Thirty-five men made up the party and their leader was Leif Ericson. His purpose was to explore the coasts which his countryman, Biarni Heriulfson, had seen several years before, when in attempting to cross from Iceland to Greenland adverse winds had driven him to lands lying far to the south, possibly the island of Newfoundland. Leif was sailing in Biarni’s ship which he had bought for the voyage. The first shores sighted they conjectured to be those which Biarni had seen. They offered no attractions. The explorers called the country Helluland, the Land of Broad Stones, and passed on to Markland, the Land of Woods, which may have been Nova Scotia. A few more days brought them to an island where they noticed a peculiar sweetness in the dew. They may have been the first “Off Islanders” to land upon Nantucket, which is noted for its honey-dew. Following the coast they came to a place “where a river flowed out of a lake.” The region was inviting but the tide was low and the explorers were obliged to wait until high water before they could pass over the broad shallows into the lake beyond. Here they disembarked and erected temporary habitations which soon gave[4] place to permanent dwellings when they determined to winter at that place. The new houses were easily constructed from the stones which abundantly covered the fields as they do even to this day.

The place seemed a paradise to the hardy voyagers. Fish of many kinds leaped from the waters of the river and bay. Salmon larger than any they had before seen were especially abundant. Many wild animals roamed through the forests, as the deer wander through the woods and pastures of Rhode Island at the present time. The denizens of the frigid zone rightly imagined that cattle might easily find provender throughout the winter, in a climate so soft and mild. They experienced no severe cold; “no snow fell and the grass did not wither much.” They had chanced upon one of the mild winters with which we are occasionally favored. Three or four times in the last thirty years the Mount Hope Lands have known seasons when there were but few snow storms and those slight, seasons when in the sheltered nooks of the forest the grass did not wither much. The next party encountered “real New England weather,” and doubtless objurgated Leif’s party for romancing concerning the climate. “The equality in length of days was greater than in Iceland or Greenland. On the shortest day the sun remained above the horizon from 7.30 to 4.30.”[4]

The dwellings having been completed, Leif divided his men into two parties in order to explore the country. One party was to remain at home while the other went abroad, and the exploring party was always to return at nightfall. Especial charge was given the men to keep together. The[5] fear of the unknown was a marked characteristic of the Dark Ages, even among the Norsemen who dreaded no human foes. One of the party was a German, Tyrker by name, a kind of foster father of Leif. He was missing one night when the explorers came home and Leif at once started in search of him with a party of twelve men. They were soon met by Tyrker, whom they welcomed with great joy. But the man acted most strangely. At first he spoke only in German, his mother tongue, and rolled his eyes and made strange facial contortions when they did not understand what he said. After a time the Norse language came back to him and he explained his queer behavior. He had chanced upon some wild grapes and the memories his discovery brought back were too much for him. Whether he had found some of the fox-grapes which are still so common in New England, or whether, as Professor Fernald conjectures, the fruit was either a wild currant or a rock cranberry, we can not know; but the adventurers were immensely pleased at his discovery. They filled the “long boat,” which was carried with them as a tender, with the dried fruit, when in the early spring they returned to Brattahlid, their home port. Because of the grapes the name Vinland was given to the region.

The return of Leif and the account his sailors gave naturally caused intense excitement in that quiet community. In the spring of 1002 Thorvald Ericson, taking his brother’s ship and probably some of Leif’s crew as guides, sailed on another voyage to Vinland. His object was to make a more thorough exploration of the country. Thirty men made up Thorvald’s party. Nothing is told of their voyage until they reached Leif’s booths in Vinland. There they laid up their ship and remained quietly through[6] the winter, living by hunting and fishing. The next year was spent in exploring the lands to the south. The second summer they turned their steps northward and in this northern expedition Thorvald was killed in a battle with the natives. His comrades buried him on the headland where he had proposed to settle. “There you shall bury me,” he told them after he had received his death wound, “and place a cross at my head and another at my feet, and the place shall be called Crossness ever after.” The winter of 1004-5 was passed in Leifsbooths gathering cargo for the return voyage. In the spring they sailed back to Greenland carrying large quantities of grapes as their companions had done. Because of Thorvald’s death the accounts of his voyage are probably more meagre than they otherwise would have been.

In 1007 the most important of the Norse expeditions sailed from Greenland. Its leader was Thorfinn Karlsefni. Thorfinn was both seaman and merchant. Sailing from Iceland to Greenland on a trading voyage, he had wintered at Brattahlid and there married his wife Gudrid. Naturally there had been much talk of Vinland the Good during the long Arctic winter and in the spring an expedition to explore the new country was fitted out. It consisted of three ships manned by one hundred and sixty men. With it went Gudrid and six other women, for it was proposed to colonize the land. Thorfinn spent the winter amid great hardships, caused by cold and lack of food, on what may have been one of the islands of Buzzard’s Bay. There his son Snorri was born, as far as we know the first child of European parents born upon the shores of the American continent. In the spring, coming at last to the place “where a river flowed down from the land into a lake and then into the[7] sea,” they waited for the high tide, as Leif had done, sailed into the mouth of the river and called the place Hop.[5] On the lowlands about them were self-sown fields of grain; on the high ground the wild grapes grew in great profusion. Deer and other wild animals roamed through the forests. The brooks as well as the bay were filled with fish. They dug pits upon the beach before the high tide came and when the tide fell the pits were leaping with fish. Just so today flounders may be caught along the Narragansett shores. The booths that Leif’s party had put up could not accommodate the new comers and additional houses were built inland above the lake. No snow fell during the winter. The cattle they had brought with them needed no protection and lived by grazing. None of the privations of the previous winter were experienced, and all things went well until the Skraelings, or natives, appeared. At first the Skraelings came only for trading. They wished to exchange skins for goods, being especially anxious to obtain little strips of scarlet cloth, and willingly giving a whole skin for the smallest strip. The Norsemen benevolently attempted to satisfy the desires of all by tearing the cloth into smaller and yet smaller pieces as the supply diminished. While the bartering was going on one of the bulls Thorfinn had brought with him appeared upon the scene, bellowing loudly. Thereupon the savages rushed to their canoes and paddled away as quickly as possible. A month later they reappeared, this time not to barter but to fight. In the combat that followed two Northmen fell and many of the Skraelings were killed. This battle convinced Thorfinn[8] that the lands though excellent in quality would be undesirable for a colony by reason of the hostility of the natives. He therefore turned his keels northward and returned to Greenland in 1010.

From this time expeditions to Vinland to procure grapes and timber became frequent. Because they had lost their novelty they ceased to be chronicled. As the saga puts it, “they were esteemed both lucrative and honorable.” One noteworthy one is given in the “Antiquitates Americanae,” that of Freydis and her husband Thorvald. The tale of Freydis is a grewsome one. She seems to have been entirely lacking in human sensibilities. Her husband murdered in cold blood all the men of a party that had opposed him but he spared their five women. Freydis seized an axe and brained them all. Possibly their mangled remains may have been buried at the foot of Mount Hope.

Other mention of Vinland is found apart from the Icelandic chronicles. Adam of Bremen in his “Historia Ecclesiastica,” published in 1073, describes Iceland and Greenland and then goes on to say that there is another country far out in the ocean which has been visited by many persons, and which is called Vinland because of the grapes found there. In Vinland, he says, corn grows without cultivation, as he learns from trustworthy Norse sources. This must of course have been the Indian corn, a grain that is hardly possible of cultivation in Europe north of the Alps.

The people of Iceland were more given to the writing of chronicles than were those of the countries of Europe, but unhappily Iceland was a land of volcanoes and eruptions were not infrequent. An eruption of Mount Hecla in 1390 buried several of the neighboring estates beneath its ashes.[9] Perhaps under those ashes may be lying other sagas that may at some time be brought again to light, as in the case of the scrolls of Pompeii. Mention of the lands that Leif discovered is found in the “Annals of Iceland” as late as 1347. The last Bishop of Greenland was appointed in the first decade of the fifteenth century and since that time the colony has never been heard of. Ruins of its houses may still be seen, but of the fate of those who dwelt in them we know nothing.

One witness there still may be to testify to the Norse visits. About thirty-five years ago a rock known by tradition but lost sight of for half a century was rediscovered on the shores of Mount Hope Bay. Upon it is rudely carved the figure of a boat with what may have been a Runic inscription beneath it. The writing was surely not graven by English hands and the Indians had no written language. May not the strange carving have been made by the axe of a Norseman? It is not remarkable that the rock was lost sight of for so many years. The inscription is inconspicuous and the rock is like hundreds of others along the shore. Moreover it was sometimes covered by the high tides of spring and fall. It has recently been removed to a more conspicuous position and may ere long be protected by a fence from the vandalism of the occasional tourist.

Fact and not fancy characterizes the Indian history of the Mount Hope Lands. First upon the scene steps Massasoit, “Friend of the White Man,” ruler of all the region when the Pilgrims of the Mayflower landed upon the shores of Plymouth. Like all the Indian sachems, Massasoit had many places of residence. He moved from one to another as the great barons of the Middle Ages moved from one castle to another, and for the same reason. When provisions[10] became scarce in one place a region where they were more plentiful was sought. One of his villages was unquestionably upon the slope of Mount Hope. Not many weeks after the landing of the Pilgrims Massasoit had paid them a visit in their new settlement. In July, 1621, Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins were sent by Governor Bradford to return the visit. Of what happened to this “embassy” and to a second sent some two years later, Winslow presented a very full account, which may be read in very nearly all of the histories of the period. It is one of the most trustworthy and valuable pictures of Indian royal state that have come down to us from colonial days. Winslow found Massasoit occupying a wigwam only a little larger than those of his subjects. The sleeping place was a low platform of boards covered with a thin mat. On this bed, says Winslow, Massasoit placed his visitors, with himself and his wife at one end and the Englishmen at the other, and two more of Massasoit’s men passed by and upon them, so that they were worse weary of the lodging than of the journey. As the sachem had not been apprised of Winslow’s projected visit, he had made no provisions for his entertainment. No supper whatsoever was secured that night, and not until one o’clock of the next afternoon was food to be had. Then two large fish, which had just been shot (with arrows, of course), were boiled and placed before the sachem’s guests, now numbering forty or more besides the two Englishmen.

In 1623 tidings reached Plymouth that Massasoit was sick and likely to die. Edward Winslow was therefore sent to visit him a second time. With him went a young English gentleman who was wintering at Plymouth and who desired much to see the country. His name was John[11] Hampden, a name destined to become famous wherever the English language was spoken. The great John Hampden was born in 1594. He would have been twenty-nine years old at this time. He had as yet done nothing whatever to make himself famous and was a comparatively inconspicuous man, notwithstanding the prominent position his family had held for centuries in England. There is no record of his presence in England at this time. Like Oliver Cromwell he may have been considering a residence in America among men of his own religious faith, and for this reason may have made a preliminary visit to this country. Green, discussing in his “History of the English People” Cromwell’s scheme for emigrating to America, says: “It is more certain that John Hampden purchased a tract of land on the Narragansett.” Most important of all, the name of John Hampden appears in the list of the Charter Members of the Colony of Connecticut.

As long as he lived Massasoit remained the firm friend of the colonists. Upon his death, in 1662, his son Wamsutta (or Alexander) headed the Wampanoag tribe for a year, and then came Philip, Massasoit’s second son. Philip was a foe to the white men, made such by English treatment of his tribe. He was one of the ablest Indian leaders this country has produced, a wonderful organizer, a skillful diplomatist. From tribe to tribe he journeyed, inducing them to rest from their interminable wars and to turn their weapons against the common enemy of all. But for an accident which caused hostilities to begin a little while before the year (1676) Philip had fixed upon, the colonists would have been swept from the land. The war began in 1675, and Capt. Benjamin Church, the conqueror of Philip, wrote an account of it. Benjamin Church was one of our[12] greatest “Indian fighters.” He had lain in their wigwams, he had studied their character. Naturally and inevitably he came at last to the leadership of the colonial forces. When Philip’s plans had all come to naught, the Wampanoag sachem came back to Mt. Hope, to make his last stand and to die. Death came to him from a bullet fired by one of his own men who had taken service in Capt. Church’s company. In 1876, on the two hundredth anniversary of his death, the Rhode Island Historical Society, with appropriate ceremonies, placed a boulder monument on the top of Mt. Hope, with this inscription:

KING PHILIP, AUGUST 12, 1676. O. S.

Beside Cold Spring on the west side of the hill a massive block of granite records that

IN THE MIERY SWAMP 166 FEET W. S. W. FROM THIS SPRING,

ACCORDING TO TRADITION, KING PHILIP FELL,

AUGUST 12, 1676. O. S.

The Mt. Hope lands should have fallen to Plymouth by right of conquest, as they were included in the territory originally granted to that colony. But both the Colony of Massachusetts Bay and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations claimed a portion of the spoils. So delegates of the several colonies were sent to argue the case before Charles II. Singularly enough another claimant appeared in the person of John Crowne, a poet. Crowne was a native of Nova Scotia. His father had purchased a large tract of land in that country which had become practically valueless because of the cession of Nova Scotia to[13] the French. He therefore asked that the small tract of land which had lately come into English possession should be turned over to him as a compensation. But Mt. Hope, though belonging to the English Crown, was not to be Crowne land. The Plymouth Colony agents claimed that the tract, comprising almost 7000 acres, part of it good soil and much of it rocky, mountainous and barren, for which they had fought and bled, should be awarded to them, more especially because it would afford to them the seaport which they lacked. Their arguments were convincing and the land was awarded to Plymouth by special grant, January 12, 1680. The king among other things demanded a quit rent annually of seven beaver skins. No other royal grant was made of conquered lands, but conflicting claims necessitated this.

Plymouth Colony at once placed the lands on the market, and September 14, 1680, sold them for $1,100 to four men of Boston, John Walley, Nathaniel Byfield, Stephen Burton and Nathaniel Oliver. The first three of these became residents of the town they founded. Of them, Byfield was the ablest and most distinguished. He came of good stock. His father was of the Westminster Assembly of Divines. His mother was sister of Juxon, bishop of London and later archbishop of Canterbury, who was a personal friend of Charles I, and attended that ill fated monarch upon the scaffold. Byfield was the wealthiest of the settlers. He had one residence upon Poppasquash near the head of that peninsula, and one upon what is now Byfield Street in the south part of the town. He was a man of unusual ability and large wealth. He was also a man of great liberality in all his dealings with the town. His public service was continuous and distinguished. His liberal mind resisted[14] the insane fanaticism of the people during their delusion on the subject of witchcraft, and in his will he left a bequest “to all and every minister of Christ of every denomination in Boston.” He lived forty-four years in Bristol, only leaving the town when his advanced age made the greater comforts of Boston necessary.

John Walley was also of good stock, his father being rector of one of the London churches. In 1690 he commanded the land forces of William Phipps in the expedition against Canada. He also, in his old age, was forced by disease to seek a more luxurious abode in Boston. Stephen Burton was said to have been a graduate of Oxford. He was undoubtedly the most scholarly man of the four proprietors. Oliver, a rich Bostonian, never resided in Bristol but sold his share to Nathan Hayman, another wealthy Boston merchant.

With men like these as sponsors for the new settlement, it was not difficult to secure settlers. The most noted among them was Benjamin Church, the Indian fighter already mentioned. Capt. Church built a house upon Constitution Street. (Church Street was not named in his honor. Upon that street stood the edifice which gave it its name, the building in which the members of the Church of England worshipped. There were many streets named for a like reason in colonial days.) He was the first representative of the town in the general court of Plymouth Colony and was many times elected to public office. In his later years he made his home in Little Compton, whence many of his descendants drifted back to Bristol. Because the town was to be the seaport of Plymouth Colony, many of the descendants of the Mayflower Pilgrims naturally came to dwell within its borders. In choosing Bristol for its name, the[15] settlers cherished a hope that, as in the case of its English namesake, it would become the great city upon the west. Boston on the east shore was the London of Massachusetts.

The new town was laid out on a liberal scale, with side streets crossing each other at right angles, and a spacious “common” in the center of the settlement. The grand articles stipulated that all houses should be two stories high, with not less than two good rooms on a floor. As most of the settlers could not well spare the time, if they had the means, for building a house with four rooms upon a floor, the “camelopard” type of dwelling was much in evidence. This presented a goodly appearance to the eye of him who stood directly in front, but degenerated greatly when one shifted his position, the roof sloping severely and persistently down to a woodpile. One chimney was deemed sufficient for a house. We should deem such a one more than sufficient. If of brick it was about fourteen feet square; if of stone, about twenty feet. All the chimneys had immense fireplaces, into which a man could sometimes walk without stooping, and all were admirably adapted to keep a house cold. The rooms were abominably drafty, and the high backed settle was an absolute necessity. A great pile of logs might be blistering the faces while the snow was drifting in through the cracks upon the backs.

The first house built is still standing just north of the town bridge. Deacon Nathaniel Bosworth was its builder, an ancestor of those who own it today. Only the southwestern part of the present structure was the work of Deacon Bosworth. The best house was naturally that of Byfield. It was two stories high, with a barn roof, and was nearly square, thirty by thirty-eight feet. It was torn down in 1833, and a hard job the destroyers had. The chimney[16] stood in the center of the house. It was built of imported bricks held together by mortar mixed with shell lime. This mortar had become hard as stone. When the chimney was overthrown it fell to the ground almost unbroken, as an oak tree would fall. Byfield had another house at the head of the harbor on Poppasquash. In each room were deep fireplaces, across which ran an oaken beam a foot square. One winter morning the owner of the house was surprised, when he came down stairs, to find the house even colder than usual. The front door was open and the floor was covered with snow drifts. As the door was never locked the phenomenon interested him but little, and he hastened out to feed his cattle. One ox was missing and the farmer went back to the house to organize a searching party, but as he opened the door and turned his eyes toward the fireplace, he changed his plans. There lay the huge creature tranquilly chewing the cud of complete contentment. It had found the door ajar, pushed it open and established itself comfortably upon the still warm ashes.

The town was founded for “purposes of trade and commerce” and early its sails began to whiten the seas. Naturally the first commerce was coastwise only. Then vessels sought the ports of the West Indies and Spanish Main, laden most frequently with that bulb whose fragrance lingers longest in the nostrils, the onion. The culture of this vegetable was one of the three things for which the town was noted for more than two centuries.

There once dwelt in Bristol a man named Sammy Usher, who was noted for his irascibility not less than for his caustic tongue. One day a visitor from Brown University was introduced to him. This young man, though a sophomore, was yet somewhat fresh, and Sammy did not like him. He[17] said, “Mr. Usher, I hear that Bristol is noted for three things, its geese, girls and onions. What do you do with them all?” “Oh,” said Usher, “we marry our girls as soon as they grow up, we ship our onions to Cuba, and we send our geese to college.” The first recorded shipment, however, was not of onions. November 6, 1686, Byfield placed a number of his horses on board the Bristol Merchant bound for Surinam. Possibly they may have been of the Narragansett pacer breed for which the south county was so long famous. Very early in the town’s history, sails were turned to the coast of Africa. The voyage was the most hazardous that could be taken, but the returns from a successful venture were enormous. There was profit on each leg of the voyage. The first leg was from the home port, with the hold filled with casks of New England rum and small crates of trinkets. One cask was ordinarily enough to secure a slave, but before the cargo was complete, all hands were likely to be down with coast fever. When the crew were again strong enough to work the vessel, the “middle passage” to the West Indies was made, and the live freight, which had been handled with as great care as are the cattle on the Atlantic transports today, was exchanged for casks of molasses. Then came the last leg of the voyage. The molasses was carried to Bristol to be converted into rum. This trade the town shared with Newport and Providence.

No stigma whatever was attached to the slave traffic as carried on in the seventeenth century and for the greater part of the eighteenth. The voyages, while always dangerous, were not always profitable. The vessels engaged in them were ordinarily small; sometimes they were sloops of less than a hundred tons. A fleet of them could be stowed away in the hold of a Lusitania. They had to be[18] small and of light draft in order to run up the shallow rivers to whose banks their human cargo was driven. Lying at anchor in the stifling heat, with no wind to drive away the swarming insect life, the deadly coast fever would descend upon a ship, and, having swept away half its crew, leave those who survived too weak to hoist the sails. The captains were, for the most part, God fearing men, working hard to support their families at home. One piously informs his owners that “we have now been twenty days upon the coast and by the blessing of God shall soon have a good cargo.” The number of negroes taken on board a ship was never large until the trade was declared to be piratical. Then conditions changed horribly. It did not pay to take more on board than could be delivered in the West Indies in prime condition. They were not packed more closely than were the crews of the privateers of whom we shall read later on.

Naturally not a few slaves found their way to Bristol. When the first slave was brought there we do not know. Nathaniel Byfield, in his will, gives directions for the disposition of his “negro slave Rose, brought to Bristol from the West Indies in the spring of 1718.” Quickly they became numerous. The census of 1774 records 114 blacks in a total population of 1209, almost one-tenth. At first they lived on the estates of their owners, and were known by his name, if they had any surname. After the Revolutionary War, when slavery had been abolished (mainly because it was unprofitable), they gathered into a district by themselves on the outskirts of the town. This region was called “Gorea” from that part of the coast of Africa with which the slave traders were most familiar. It continued to be known as such until the buildings of the great[19] rubber works crowded it out of existence in the early ’70s of the last century.

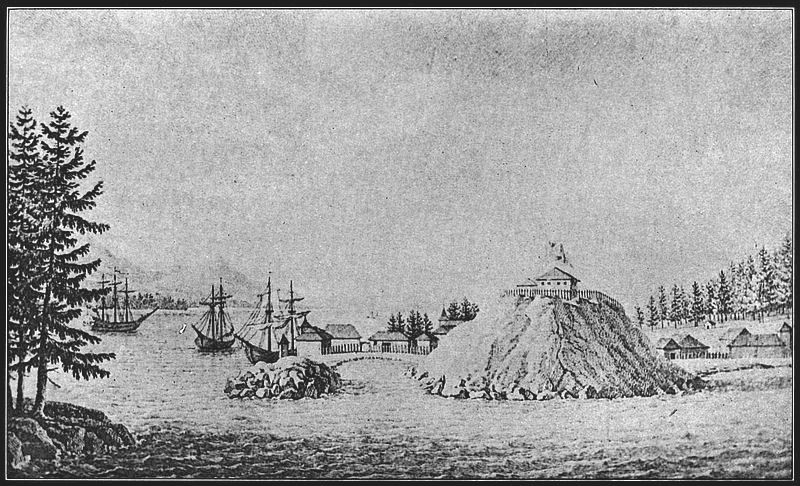

Naturally and inevitably the town became involved in the contest that resulted in the independence of America. The affair of the Gaspee was the first in which her people participated. The Gaspee was an armed schooner stationed in Narragansett Bay for the prevention of smuggling. Smuggling was as much in vogue in American waters as in the waters surrounding the British Isles, and was regarded with no more disfavor in one case than in the other. The commander of the vessel was Lieutenant Thomas Duddington, a man who was entirely lacking in tact, and who carried himself with such haughty arrogance as to make himself most obnoxious. One day while chasing one of the packet sloops that plied between New York and Providence, he ran aground on Namquit (now Gaspee) Point. His “chase” escaped and carried the joyful tidings of his plight to Providence. At once drummers were sent through the streets proclaiming the situation of the vessel, and calling for volunteers to destroy her before the next high tide. Eight long boats were furnished by John Brown, the leading merchant of the town, which were quickly filled by a rejoicing band. No attempt at disguise was made by those who took part in the expedition, but the oars were muffled to enable the boats to make the attack without being seen. As they drew near the vessel, a little after midnight, they were joined by a whaleboat containing a party from Bristol under the command of Captain Simeon Potter.[6]

Their approach was discovered by the watch upon the Gaspee, and as the boats dashed forward they were fired[20] upon from the schooner. The fire was at once returned by the attacking party, and the vessel was boarded and captured after a short but desperate struggle. In this struggle Lieutenant Duddington was wounded, though not seriously. The crew were captured, bound and set on shore. The vessel was set on fire and completely destroyed. Then, having been entirely successful in their expedition, the boats rowed joyfully homeward. Those who took part in the exploit made no effort to conceal it and some of them even boasted of what they had done. The British Government at once offered a large reward for information that would lead to the conviction of the bold offenders. Some of them were among the foremost men in the Colony and almost every one knew their names, the name of Abraham Whipple especially being on the lips of all the people, but no man of any character could be found to testify against them and none of them were ever brought to trial. The affair took place on June 10, 1772. It was the first contest in which British blood was shed in an expedition openly organized against the forces of the mother country, and it differed from all the other preliminary encounters because of the character of those engaged in it. Other outbreaks were the work of an irresponsible mob. Crispus Attucks, for instance, who fell in the so called Boston Massacre, was a mulatto and the men whom he led were of his type. But some of the leading men of Rhode Island sat on the thwarts of the nine boats, and their boldness seems almost incredible to us of the present day. It shows that while public sentiment at Newport and New York and the other great seats of commerce along the coast may have favored the king, the people of the Providence Plantations were already prepared to sever their relations with England.

[21]

The only “lyric” to commemorate the affair came from the pen of Captain Thomas Swan of Bristol, one of those who took part in it. His effusion has never appeared in any history of American literature, for good and sufficient reasons, but it is printed in full in Munro’s “History of Bristol.” The participation of the Bristol men in the Gaspee affair is often denied by “out of town” people. I have no doubt respecting the matter. My own grandmother, born in 1784, the daughter of a soldier of the Revolution who was born in 1762 and lived until 1821, and whose grandfather, born in 1731, lived until 1817, firmly believed in it. She had had opportunities for talking the subject over with two generations who were living on June 10, 1772.

In January, 1881, Bishop Smith of Kentucky, born in Bristol in 1794 and a graduate of Brown in 1816, wrote to me calling my attention to a slight difference between the “Swan Song,” as I had given it in my “History of Bristol,” and a version pasted upon the back of a portrait of Thomas Swan’s father by Thomas Swan himself. Capt. Swan was Bishop Smith’s uncle. The Bishop wrote, “I should not have troubled you on so inconsiderable a point had not the tradition in our family been that the Bristol boat was manned by men in the disguise of Narragansett Indians.”

When Bishop Smith penned those lines several men were living in Bristol who had heard the story from Captain Swan’s own lips. He delighted in telling it and was accustomed to give the names of Bristol participants. Those names had unhappily escaped the memory of his auditors. The correspondence on the subject of the Gaspee, which occurred during the Revolutionary War between Abraham Whipple and Captain Sir James Wallace, the commander of the British naval forces in Narragansett Bay, is worthy of another reproduction:

[22]

Wallace to Whipple:

“You, Abraham Whipple, on the 10th June, 1772, burned his Majesty’s vessel, the Gaspee, and I will hang you at the yard arm.—James Wallace.”

Whipple to Wallace:

“To Sir James Wallace; Sir; Always catch a man before you hang him.—Abraham Whipple.”

On October 7, 1775, the town was bombarded by a British fleet. The squadron consisted of three ships of war, one bomb brig, one schooner and some smaller vessels, fifteen sail in all. They had sailed up from Newport under the command of Sir James Wallace. A boat’s crew was sent on shore to demand sheep from the town. As they were not forthcoming, the boat returned to the ship and shortly afterward the whole fleet began “a most heavy cannonading, heaving also shells and ‘carcasses’ into the town.” (Carcasses were vessels bound together with hoops and filled with combustibles.) Singularly enough, no one was killed, though many buildings were struck by balls. The next morning the sheep demanded were furnished and the fleet sailed away. An epidemic of dysentery was raging at the time, seventeen persons having died within a fortnight; and the fact that at least one hundred sick persons would have to be removed if the cannonading was resumed influenced the town committee to provide the supply demanded. One life, however, went out because of the bombardment. The Rev. John Burt, the aged pastor of the Congregational Church, had for a long time been sick and feeble. When the air was filled with missiles he fled from his house, no one seeing him, and wandered away, weak and bewildered. The next morning, as he did not appear in the meeting house at the hour of service, his congregation[23] went out to seek him. They found at last him lying dead upon his face in a field of ripened corn.

About three years later, on Sunday, May 25, 1778, most of the houses in the center of the town were burned by the British. Five hundred British and Hessian soldiers landed on the “West Shore,” marched quickly through Warren to the Kickamuit River, and there burned seventy or more flat-boats that had been gathered together by the colonists for the purpose of making an expedition against the enemy. The raiders set fire to some buildings in Warren and then proceeded along the main road to Bristol, making prisoners of the men found in the farm houses standing near the highway. A force of perhaps three hundred militia had been hastily gathered at Bristol to oppose them. But, as is almost always the case, the number of the marauding troops was greatly exaggerated and the American commanding officer did not deem himself strong enough to oppose them. Withdrawing in the direction of Mount Hope he left the town to their mercy. The torch was first applied to Parson Burt’s house, which stood near the Congregational Meeting House.

Mr. Burt had died during the bombardment, as has been before related, but he had been fearless in his denunciation of royal tyranny during his life and his house was burned as a warning. Then the other buildings southward along the main street were set on fire, including the residence of Deputy Governor Bradford, this last being the finest house in town. One of the Governor’s negro servants had just begun his dinner when he saw the flames bursting forth. He was quite equal to the occasion. Running to the burying ground on the Common, not far away, he seated himself, frying pan in hand, upon a tombstone and calmly[24] finished his meal. Thirty or more buildings were burned, among them being the edifice of the Church of England, Saint Michael’s Church. This last structure was destroyed through a mistake, the incendiaries supposing that they were burning the Dissenters’ Meeting House. The sexton of Saint Michael’s refused to believe that his church was burned. “It can’t be,” he said, “for I have the key in my pocket.” From this time until the close of the war the tread of marching feet was heard almost daily. The soldiers, however, were only militiamen summoned hastily together to defend their homes. They were poorly drilled and still more poorly armed, the kind of soldier that springs to arms at an instant’s call. The immediate danger having passed, they returned to their farms and their workshops.

Until October 25, 1779, when the British forces left Newport, the fortunes of those who dwelt upon the Mount Hope Lands were hazardous in the extreme. Lafayette had established his headquarters in the north part of the town but was soon forced to remove them to “a safer place behind Warren.” The peninsula was so easily accessible that raids upon its shores were frequent. One result of the marauding expeditions was the cutting down of the forests that had lined the shores of Narragansett Bay. This was especially notable in the case of the island of Prudence, just at the mouth of Bristol harbor. Today the island is almost treeless, no attempt at reforestation having been made. The people of Bristol were wise in their generation and now from the harbor the town seems to nestle in a forest.

The winter of 1779-80 was one of the most severe ever known in the Colonies. For six weeks the bay was frozen from shore and the ice extended far out to sea. Wood in most of the towns sold for $20 a cord. The prices of[25] all kinds of provisions soared in like manner. Corn sold for four silver dollars a bushel and potatoes for two dollars. What their prices were in the depreciated Rhode Island paper currency we can only imagine. While the bay was still frozen some of the barracks on Poppasquash, that had been used by the French allies, were moved across the harbor on the ice. One of them is still used as a dwelling house. It stands on the west side of High Street just north of Bradford. From 1774 to 1782 the population of the town decreased 14.6 per cent. More noteworthy still, in that same period the percentage of decrease in the case of the blacks was more than thirty per cent.

In 1781 the town was first honored by the presence of George Washington. He passed through it on his way to Providence. It was a great day for the people of the place. They all turned out to greet the hero, standing in double lines as he rode through the streets. “Marm” Burt’s school children were especially in evidence. This lady was the widow of the Parson Burt who had died during the bombardment. She had sustained herself since her husband’s death by keeping a “dame’s school.” To impress the occasion upon the minds of her pupils she made them learn these lines:

Imagine the General’s emotions as he heard them singing the verse, at the top of their voices of course, as he passed.

Washington afterward made several visits to the town. In 1793 he spent a week at the home of Governor Bradford, at “the Mount,” Bradford being then a member of the United States Senate. The Bradford house is still standing.

[26]

Rhode Island was the last of the “Old Thirteen” to adopt the Federal Constitution. Then as always she chafed at the domination of Massachusetts. Because Bristol had been a part of Massachusetts before it became a part of Rhode Island it was still greatly influenced by the ideas of the “Bay Colony.” When in 1788 the question of adopting the Constitution was submitted to the people of Rhode Island, Bristol and Little Compton (which had also been a part of Massachusetts) were the only towns in which a majority in favor of the adoption was obtained. A great celebration took place in 1790 when the State became a member of the United States of America.

At once the energy which had lain dormant during the Revolutionary War revived. Commerce again became active. Evidence of this was manifested by the building of new distilleries. One, erected by the leading firm of ship owners, was opened in 1792. They were preparing for a renewal of the trade with Africa. For thirty-five years thereafter two hundred gallons of rum were here each day distilled. At one time five distilleries were in active operation. The last of them closed its doors in 1830, the business having ceased to be profitable.

In the first quarter of the last century two great religious revivals transformed the town. They began in Saint Michael’s Church in the rectorship of Bishop Griswold. The town then numbered about two thousand inhabitants, almost all of whom were more or less connected with the sea. The first among the laymen to take part in the movement was a sea captain who had just returned from a voyage to the Island of Trinidad. Before he left Bristol, the unwonted fervor of Bishop Griswold’s sermons and discourses had turned his thoughts toward the attainment of the holier[27] and higher life, whose glories the bishop was ever placing before his people. The awful solemnity of the ocean had completed the lesson. On Saturday night he returned from his voyage. The next day, when the bishop had finished his sermon, the emotions that stirred the soul of the sailor entirely overcame the modesty that usually kept him back from the public notice. Rising from his seat, he went forward to the old wine-glass pulpit in which the preacher was yet standing, and conversed with him earnestly for a few moments, while the congregation looked on with amazement at the unusual interruption. With that benignant smile which marked his gentle nature, Bishop Griswold assented to the request that was preferred; and placing his hand upon the shoulder of the eager enthusiast, he turned to the congregation and said: “My friends, Captain —— wishes to tell you what the Lord has done for his soul.” Then the quiet sailor told the congregation the story of the change that had been wrought in him; told it without a thought of the unusual part he was assuming; told it in the simplest words, with no attempt at eloquence or effect, but with the wondrous power of God’s love so plainly before his eyes that the minds of all his hearers went with him upon the sea, and felt the struggle which had brought his soul out of darkness into light. Never, even, had the inspired words of their pastor stirred the people of St. Michael’s Church more strongly. When he ceased there was hardly a dry eye in the congregation. Only a few well chosen words did the bishop add to intensify the lesson, and then dismissed his people with the usual benediction.

From that day the revival became general. Through the town it spread, until the minds of all were turned to[28] thoughts of the life that was to come. The sound of the workman’s hammer was unheard for a season, the horses stood idle in their stalls, the noise of merry laughter ceased as the crowds of serious worshippers poured onward to the churches. For days these remarkable scenes were to be witnessed; their effect could be observed for years.

The second revival came in 1820. Like the first it began in Saint Michael’s Church. It lasted for about three months. The first meeting was held in a private house. The Rev. Dr. Stephen H. Tyng, writing sixty years later, said: “It was with unbounded surprise that I went into the house at the hour appointed. It was crowded in every room, staircase and entry, as if some unusually crowded funeral were there. But for ministering to this people, hungry for the bread of life, I was there alone. They had placed a Bible and Prayer-book on the first landing of the stairs. The people were crowded above me and below me, as far as my eye could reach, in the most eager attention to the Word. It was the most solemn assembly I had ever seen, and its impression upon my mind and memory was overwhelming and abiding. But this was the commencement of months of work of a similar description, and from this day we had a similar meeting appointed for every evening. These were held in various rooms and houses throughout the town. The evening meetings were usually held in the Academy Hall. My whole time for about three months was given up to this one work. Three times every day I was engaged in addressing different assemblies in different parts of the town and of the surrounding country, and in conversing with awakened and anxious persons connected with these meetings. Such a scene in human society as Bristol then displayed, I had never imagined. The whole[29] town was given up to this one work. The business of the world was for a time suspended. The stores were in many instances closed, as if the whole week were a Sabbath.”

As in the former case the work spread through all the churches. Crowds came from surrounding towns to gaze upon the remarkable spectacle the town afforded. Such revivals would now be impossible. The busy manufacturing town of today would pay slight attention to exhortations to which the ears that were accustomed to tales of horrible disaster upon the ocean lent ready attention. Moreover, the descendants of the old colonial stock are comparatively few in number, and the new foreign element which forms the great majority of the population is not to be moved by religious appeals as were those whose lives were dominated by Puritan traditions.

The maritime element always furnished the most picturesque part of the Bristol story. Until half a century ago the boys of the town had the names of the famous ships and the exploits of the most famous captains at the tongue’s end. The most noted captains were Simeon Potter, John De Wolf and James De Wolf, of whom detailed accounts will be given later. We idealized those seamen, especially Simeon Potter. One sailor who was not a captain but a ship’s surgeon had had a most remarkable experience. He was an inveterate smoker and his inordinate use of the weed once saved his life. He was shipwrecked upon a cannibal island in the Pacific ocean. His fellow sufferers were all eaten by their captors. Because he was so flavored with tobacco, he was not deemed fit to be eaten at once by the savage epicures, and so lived to be rescued. He was also a most profane man. One day after a long attack of fever, which had wasted him almost to a skeleton, he ventured[30] out for a walk. Unfortunately, he had not noted the wind. He wore a long cloak and the wind was fair and heavy. Having once started before it, he was not able to stop, but went on, gathering speed and scattering profanity, until friendly arms at last rescued him, entirely exhausted except as to his supply of oaths. Depraved boys when caught smoking sometimes brought forward his case in extenuation of their own crime.

Boyish sports before the introduction of baseball in the “early ’60s” were largely nautical. As a matter of course every boy learned to swim almost as soon as he learned to walk. Before his anxious mother had really begun to worry about him he was diving from a bowsprit or dropping from a yard arm. One man whom I know still regards a forced swim of about half a mile which he took from an overturned skiff, at the age of nine, as the most delightful episode of his career. (He forgot to tell his mother about it until a considerable time, i.e., the swimming season, had elapsed.) One of the amusements of that olden time was unique. When we were about ten years old we were wont, as soon as school was dismissed, to hasten down to the wharves, “swarm” up the rigging of some of the vessels lying there, and having reached the point where the shrouds stopped, to “shin up” the smooth topmast and place our caps upon the caps of the masts. The one who got his cap on a mast first was of course the best boy. Singularly enough, I never remember to have proclaimed to my parents the proud occasions when I was “it.” My great chum in those days was Benjamin F. Tilley, who died quite recently, an Admiral in the United States Navy and one of the best loved officers in the service. When he was in Providence a few years ago, in command of the gunboat Newport, we indulged[31] largely in reminiscences of our boyhood, and among other things “shinned” up those masts again. Very strangely Tilley could not remember that he had ever proclaimed to his parents that he was “it.” Modest always were the Bristol boys in the days of my youth. Looking back upon these episodes with the added knowledge fifty years have brought, I feel sure that if I had told my father of my prowess, he would have said in his quiet way, “Perhaps you would better not say anything to your mother about it,” and would have gone away chuckling. He had been “it” himself. For we boys were simply exemplifying the traditions of our race. We were only doing what our forebears had done for generations.

In the earliest years of the town the names of streets in cities across the ocean were more familiar to its inhabitants than were those of the towns of the other Colonies. In 1690 fifteen of its vessels were engaged in foreign commerce, and the number of such vessels steadily increased until the Revolutionary War. When that struggle broke out fifty hailed from the port. Add to this the number of craft of every description engaged in the coasting trade and one can easily imagine the crowded condition of the harbor. Ship building was at one time a prominent industry. Statistics are not readily accessible but we know that from 1830 to 1856 sixty vessels were here built and rigged. After 1856 none of any importance were constructed until, in 1863, the Herreshoffs began to send from their yard the yachts that were to “show their heels” to all rivals. The decline of commerce dates from the revival of the whale fishery. In the earliest colonial days whales were captured along the coasts of New England by means of boats sent out from the shore whenever one of the great[32] fishes came in sight. This was not infrequently. (It was a whale cast up on the shore that saved Thorfinn Karlsefni from starvation when the Norsemen made their second visit to Vinland.) In the year 1825 the first whaler was fitted out for a cruise. The venture was unusually successful and other ships were quickly placed in commission. In 1837 the arrival of sixteen vessels “from a whaling cruise” is recorded on the books of the Custom House. The most noted of those whalers was the General Jackson, prize of the privateer Yankee. Of her more anon. In 1837 the Bristol whaling fleet numbered nineteen ships.

The bell which summoned the operatives of the first cotton mill to their work really sounded the death knell of the shipping industry. The man whose maritime ventures had been most profitable was quick to recognize the fact. James De Wolf was the first of Bristolians to transfer his capital from ships to factories. With the building of mills agriculture began to decline though for more than half a century onions and other vegetables continued to be exported to the West India Islands. The erection of the great buildings of the National Rubber Company completed the transformation of the town.

Very different is the place from the old Puritan town of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; very different indeed from the Bristol of sixty years ago. Sixty years ago the Puritan traditions still dominated. This fact was especially evident on Sunday. That day was observed with the strictness of the old Puritan Sabbath. Worldly amusements were frowned upon. Every one was expected to go to church in the morning, and a very large proportion of the population attended a second religious service in the afternoon or evening. If golf had been known no one[33] would have ventured to play it. Social ostracism would have followed any attempt at a match game of ball. The only foreign element was the Irish. Very nearly all the Irish had been born on “the old sod.” Today the Irish element is almost the dominant one and the descendants of the first immigrants are as thoroughly American in their ideals and sentiments as are those who trace their ancestry to the Founders of 1680. Sixty years ago there were perhaps a dozen names upon the tax lists that were not derived from the British Isles. No foreign tongue except the Spanish of the frequent Cuban visitors was heard upon the streets. Today the Italian language is everywhere heard and Italian names fill the pages of the directory. With the Italians have come also Canadian French and Portuguese. Walking over the “Common” one day not long ago I passed three groups of men and boys and heard from them not one word of English. One group was Italian, another French, the third Portuguese.

In the olden days the business was transacted along the wharves on Thames Street. That street was crowded with drays loaded with the products of every land, while sailors of all nations lounged about the water front. Today a sailor is a rare sight. The commerce has vanished and not a vessel of any size hails from the port. Even the pronunciation of the name of the street by the water has been changed and most of the dwellers upon that thoroughfare do not know that they are living upon the “Tems” street of our fathers. By day even in summer the streets of the town are almost empty, except for the visitors, and half the people are at work in the factories. But there is immense life in the place yet. The population is increasing by leaps and bounds and the wealth per capita is increasing[34] in the same way. When the great mill wheels cease to turn, a hurrying throng of operatives crowds the highways. Although they are now for the most part alien in speech and thought, their children, born in the old colonial port, will grow up imbued with the spirit of the place and will be Americans, Americans without the hyphen. The old seafaring spirit still exists, though mightily transformed. No longer do Bristol sails whiten far distant seas, no longer do the argosies bring into the harbor the products of India, the silks of China and Japan. From the port today go forth vessels of a very different type. They lack the capacious holds of the olden days but they carry sails larger than any the old captains ever dreamed of. Their business is not to carry merchandise; they sail forth from Narragansett Bay to lead the yachting fleets of the world.

[35]

[36]

[37]

Most famous among the names of the old sea captains of Bristol is that of Simeon Potter. For almost half a century Potter was the most conspicuous figure in the town in which he was born. He was also one of the influential men in the Colony and State of Rhode Island for a large part of that time.

Simeon Potter was born in Bristol in the year 1720. His father was not a man of fortune and the boy’s education was almost entirely neglected. His letters, even in advanced age, are those of an illiterate man who, apparently, had never attempted to remedy the deficiencies of his youth. Perhaps this is not to be wondered at. He went forth from Bristol an humble sailor lad whose only possessions were a sound body and an imperious will. After a comparatively few years spent upon the ocean he returned to his native town with a purse overflowing with riches, a man to be looked up to for the rest of his life.

His wealth was acquired in “privateering,” and tales of his captures upon the sea, and especially of his wild marauding descents upon foreign coasts, were familiar as household words to the ears of the Bristolians of three-quarters of a century ago. Those tales lost nothing in the telling and in them Potter came to be endowed with attributes he never possessed. This was especially the case with his stature. Like Charlemagne he continued to grow taller with each fifty years after his death. He came in time to be pictured as a giant in size and strength, a man whose success was[38] largely due to the might of his arm, and not to any especial mental ability. It was not until the narrative which follows had been brought to light that we were able to see him as he really was, a slight man. Possibly his great wealth rather than an overpowering personality may have been the cause of his large influence. His fortune was estimated at a quarter of a million dollars, which was an enormous sum for those days.

He plunged gladly into the conflicts of the turbulent age, and by a happy chance came forth from them all without serious injury. When wars ceased his restless energy forced him into constant litigations; he seemed never to be happy unless he had some legal contest on his hands. His intense pride had much to do with this. Like many self-made men he could brook no opposition; he exacted from his townsmen the deference invariably rendered by seamen to the quarter-deck, and never forgot that his success was due to his own unaided efforts. Very soon after the Prince Charles had returned from the raid upon Oyapoc it was visited by some officers from a British man-of-war then lying in the harbor of Newport. They were greatly pleased with the trim, man-o’-war appearance of the privateer and expressed their approbation of its commander. Unfortunately they did so with a patronizing condescension that was exceedingly galling to the young captain. When at last one of them ventured to ask “why he did not apply to his Majesty for a commission as the king would undoubtedly give him a larger and better ship” he could no longer contain himself. “When I wish for a better ship I will not ask his Majesty for one, I will build one myself,” he said, and, turning on his heel, left the Englishman wondering what he could have said that seemed so offensive.

[39]

Potter left the sea and came back to Bristol to live just after the town had been transferred from Massachusetts to Rhode Island. He was first chosen to represent the town in the General Assembly in 1752, and from that time until the Revolution, when he had become an Assistant, an office corresponding to that of a Senator today, his voice was continually heard in the colonial councils. After the war had really begun his zeal (though not his pugnacity) seems to have waned and he ceased to take an active part in the affairs of either town or State. Possibly the larger ability, the increasing influence and the more striking personality of his townsman, Governor William Bradford, may have had something to do with Potter’s retirement from participation in public life.

However that may be, when the contest that was to result in the independence of the United Colonies began he plunged into it with immense delight. These lines in his own handwriting, preserved to the present day by a descendant of one of his sisters (he left no children), show clearly his mental attitude at that time:

His participation in the destruction of the Gaspee has been already described. When the office of Major-General of the Rhode Island Colonial Forces was created his zeal and energy had so impressed his fellow members of the General Assembly that he was chosen to fill it. His tenure of office must have been brief. In 1776 he had been chosen Assistant (Assistants were elected by the vote of all the freemen of the Colony), but he did not present himself at many meetings of the Assembly. In fact so neglectful was he of his duties that a vote was passed requesting his reasons for absenting himself, and demanding his attendance at the next session. Undoubtedly the increased taxes had something to do with it. He was the wealthiest citizen of Bristol and one of the richest men in the Colony, and the possession of money was his chief delight. He could not bear to see it taken away from him even though the independence of the Colonies might thereby be assured. (One day a young nephew was talking with him and lamenting his apparent lack of success. “How, Captain Potter,” said he, “shall I go to work to make money?” “Make money,” said Potter, “make money! I would plow the ocean into pea porridge to make money.”)

In 1777 his name appears for the last time in the Colonial Records. At the Town Meeting held in Bristol in May of that year “Colonel Potter was chosen Moderator, but after the usual officers were elected he withdrew and refused to[41] serve any longer.” A tax collector’s account was then presented showing that he had neglected to pay all his taxes. Three years later, May 10, 1780, it was voted in Town Meeting “That the Assessors make enquiry and make report to the town at the adjournment of the meeting, what part of Colonel Potter’s taxes remain unpaid, and that Mr. Smith, the collector, be desired to apply to the Assessors of the town of Swansey to know at what time said Potter began to pay taxes in said town, and what part of his personal estate has been rated from time to time in said town.” Although he still retained his household in Bristol he had taken up his residence in Swansey, where the rate of taxation was considerably less than that of Bristol. In that Massachusetts town he continued, nominally, to reside for the rest of his life. Notwithstanding his residence in another State he still continued a member of Saint Michael’s Church. In 1792 a vote of the Vestry was passed, thanking him for painting the church edifice, and for other benefactions, and in 1799 he presented a bell (with a French inscription) to the parish. His name headed the list of vestrymen from 1793 until his death. He died, at the age of eighty-six, February 20, 1806, leaving no children. His estate was by will divided among his nine sisters and their descendants. All the beneficiaries did not fare alike. He had his favorites and his strong prejudices. As is almost always the case popular estimate had exaggerated the value of his property. Instead of a quarter of a million, less than half that amount was divided among his heirs. The inventory showed that he had made a great many “wildcat” investments.

From his house on Thames Street the old captain was borne to his last resting place in the burying-ground upon[42] the Common. It was the most impressive funeral the town had witnessed. All the people turned out to see the long procession, and to take part in it. The privateering exploits of his early life were again retold, the innumerable legal battles of his later days were again recounted. Full of strife and tumult were the centuries in which his life had been passed, stormy and passionate his own career had been. He was perhaps the last, he was certainly the most successful, of the old sea captains who, as English subjects, had sailed forth from Narragansett Bay to make war as privateersmen upon the foes of Great Britain. But among those who followed his corpse to its final resting place were men who in less than a decade were to sail out from Bristol harbor in a little private armed vessel whose success as a privateer was to surpass his wildest imaginings, a vessel that was to collect from English merchants a tribute many times exceeding that which he had exacted from the enemies of England. The story of that vessel will be told in the last chapter of this book.

Potter was most noted for his raid upon the coast of French Guiana of which an account follows. He was captain of a typical American privateer when Narragansett Bay was noted throughout the Colonies as a nursery of privateersmen. Rhode Island furnished more privately armed vessels for the service of the mother country during the eighteenth century than did any other American Colony. From the year 1700 to the Revolution at least one hundred and eighty such ships sailed out from its ports. They were long and narrow, crowded with seamen for their more speedy handling, and manœuvered with a skill that placed the slower ships of the French and Spaniards entirely at their mercy. They carried long guns which enabled them[43] to disable their adversaries at a distance, thus preventing their enemies from inflicting any damage in return. Because built for speed they were of light construction. A broadside from a man-of-war would have gone crashing through their hulls and sent them at once to the bottom of the sea, but the seamanship of their captains always kept them out of reach of such a broadside. Their greatest danger was from the gales that drove them upon a rocky coast. Then no skill of their captains could save them. Their slight frames were quickly broken to pieces, sometimes with the loss of every man on board. The Prince Charles of Lorraine was wrecked upon the rocks of Seaconnet Point not long after the voyage herein described.

The kind of warfare in which they engaged would not now be regarded as honorable, yet it was then approved by all nations. Not only did they seek prizes upon the ocean; a descent upon the coast of the enemy, a plundering of a rich town especially if it was undefended, was an exploit from which they derived the liveliest satisfaction. They preferred that kind of an expedition, for, as was always the case with private armed ships, their aim was simply to acquire wealth for themselves, not to inflict unprofitable damage upon their adversaries. Privateering was only a species of legalized piracy as far as these raids were concerned. Happily the ruthless bloodshed and the outrages which characterized the raids of the buccaneers and other pirates were never charged against sailors on the legally commissioned private armed ships. Their trade was brutal but they carried it on with the approbation of their fellow men because it was a custom that had prevailed from time immemorial.

Very rarely have records of their raids been preserved,[44] more rarely still accounts written by their victims. The one which follows was discovered and made public some three-quarters of a century ago by Bishop Kip of California. At the sale of a famous library in England he purchased a set of the “Letters of Jesuit Missionaries from 1650-1750,” bound in fifty or more volumes. In 1875 he published a volume containing translations of the letters relating especially to American history. From this volume, which has long been out of print, the following account is taken.

The owners of the Prince Charles of Lorraine were Sueton Grant, Peleg Brown and Nathaniel Coddington, Jr., of Newport. Simeon Potter of Bristol was her captain, and Daniel Brown of Newport was her lieutenant. Among the Bristol men on the privateer were Mark Anthony De Wolf (founder of the family destined to become most famous in the history of the town), clerk; Benjamin Munro, master; Michael Phillips, pilot; William Kipp and Jeffrey Potter, the last being probably an Indian slave of Potter. Upon her return from her cruise Captain Potter was summoned before an admiralty court, having been accused of certain high handed, not to say illegal proceedings. Among other things he was charged with having fired upon a Dutch vessel while his ship was lying at anchor in Surinam, Dutch Guiana. He proved to the satisfaction of the court that he had fired upon the Dutch ship at the request of the Captain of the Port, in order to “bring her to,” his own ship being between the vessel and the fort at the time and so preventing the fire of the fort. The admiralty judge decided that Potter had not been guilty of the offences charged, and that he had shown zeal and enterprise worthy of commendation and imitation. The trial proceedings combined with Father Fauque’s narrative give a complete history of the cruise.

[45]

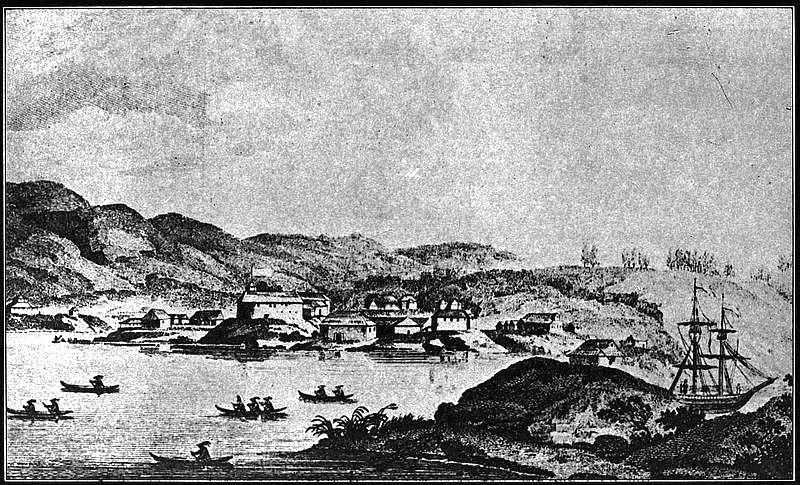

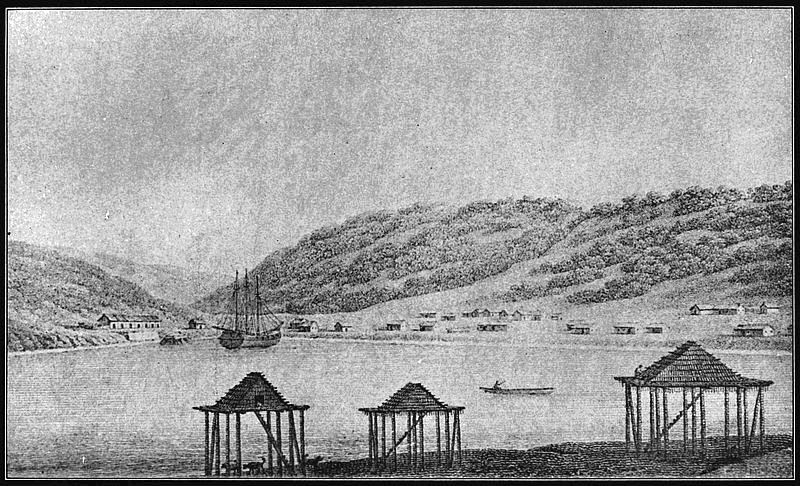

The privateer sailed from Newport September 8, 1744, and arrived at “Wiopock, twelve leagues to the windward of Cyan,” October 28. Up to that time she had taken no prizes. Upon his arrival Potter took thirty-two men and made a descent upon the town. They reached it at midnight and were at once fired upon by its garrison, Captain Potter receiving a bullet in his left arm. Of course they took the fort; garrisons in the tropics were never equal to privateersmen as fighters. They took some twenty prisoners (the other defenders having promptly fled), six cannon and from sixty to seventy small arms. They remained at Wiapock twelve days while they sacked the town, taking from it everything of value. Some of the company were sent up the river to plunder plantations. All things taken were carried to Barbadoes and there condemned as French property, with the exception of some slaves detained at Surinam and some personal property which Potter sold at a “vandue” on his ship. Having stripped Wiapock (the name of the place was Oyapoc but American and English captains were never strong on spelling) to their hearts’ content, they sailed to “Cyann” (Cayenne) and dropped anchor at that place November 11. There they tarried four or five days, during which they sent plundering expeditions up the river. One of these came to grief on a shoal. The twelve men who manned the boat were attacked by one hundred and thirty soldiers, three of them were killed, four were wounded and the others carried to Cyann fort as prisoners. Thereupon Potter sent a flag of truce to propose an exchange of prisoners. The exchange was arranged and among those returned by the Americans was “a priest,” Father Fauque. Then the Prince Charles sailed to Surinam well satisfied with what had been accomplished. At Surinam Captain[46] Potter gave an entertainment to two English merchants and some masters of ships that were at anchor in the port. Seamen of that day were not always total abstainers and after the banquet the “vandue” was had of which mention has already been made. The prices obtained for the plunder were doubtless satisfactory for the most part to the sellers, but not in all cases. The goods sold “to the value of thirty or forty pieces of eight.” They belonged to the “company” and the captain purchased many of them on his own account thereby furnishing cause for the suit brought against him on his return to Rhode Island, from which suit he came out triumphant. Immediately after the sale the seamen demanded their share of the proceeds. Captain Potter told them they were still in debt to the owners for advances made and as his arguments were enforced by a drawn sword they were admitted to be valid.

In his testimony before the admiralty court the Indian, Jeffrey Potter, was more specific as to the plunder secured at Wiapock than any other witness. He testified that they took seven Indians and three negroes, twenty large spoons or ladles, nine large ladles, one gold and one silver hilted sword, one gold and one silver watch, two bags of money, quantity uncertain; chests and trunks of goods, etc., gold rings, buckles and buttons, silver candlesticks, church plate both gold and silver, swords, four cannon, sixty small arms, ammunition, provisions, etc. But the wealth secured on this raid could not have been very great. French Guiana at the present time has a population of only 30,000, of whom 12,500 live at Cayenne. The number of people then living at Oyapoc was much smaller than the population of today. The town burned by the marauding expedition sent up the river contained not more than seventy houses, and anyone[47] who has visited the countries lying along the north coast of South America knows that “the wealth of the tropics” is a wild figure of speech as far as the house furnishings are concerned.

Equally wild are some of the accounts of the raid. One writer states that “there can be no doubt that in this cruise Captain Potter and his command invaded and desolated 1500 miles of the enemy’s territory; that on the Spanish Main in his march he visited churches and dwellings, and brought from the field of his exploits large amounts of booty.” This writer was but repeating the tale as it had been told him in his childhood. He had never deemed it necessary to verify it. If he had considered the matter he would have realized that French Guiana is not a part of the Spanish Main at all, and a glance at the map would have shown him that between Cayenne and the mouth of the Orinoco River, where technically the “Spanish Main” begins, lie the hundreds of miles of coastline of Dutch and British Guiana. No privateer of the size of the Prince Charles could possibly have carried provisions and water sufficient for such a cruise if the expedition had been made in the vessel itself, and no ship’s crew of the size of that which Potter commanded could, by any stretch of the imagination, have made such a journey overland. Moreover no mention whatever of the Spanish Main, or of booty except that obtained at Cyann and Wiapock, is to be found in the records of the admiralty court. The statement affords an excellent illustration of the astounding growth of popular traditions.

[48]

Letter of Father Fauque, Missionary of the Society of Jesus, to Father ——, of the same Society, containing an Account of the Capture of Fort d’Oyapoc by an English pirate.[7]

At Cayenne, the 22d of December, 1744.

My Reverend Father,—The peace of our Lord be with you! I will make you a partaker of the greatest happiness I have experienced in my life, by informing you of the opportunity I had of suffering something for the glory of God.

I returned to Oyapoc on the 25th of October last. Some days afterwards, I received at my house Father d’Autilhac, who had returned from his mission to Ouanari, and Father d’Huberlant, who is settled at the confluence of the rivers Oyapoc and Camoppi, where he had formed a new mission. Thus we found ourselves, three missionaries, together; and we were enjoying the pleasure of a reunion, so rare in these countries, when divine Providence, to try us, permitted the occurrence of one of those wholly unexpected events which in one day destroyed the fruit of many years’ labor. I will relate it, with all the attending circumstances.