*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 67188 ***

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them

and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or

stretching them.

Cover created by Transcriber

and placed into the Public Domain.

THE POWDER OF

SYMPATHY

OTHER BOOKS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fiction

Parnassus on Wheels

The Haunted Bookshop

Kathleen

Tales from a Rolltop Desk

Where the Blue Begins

Essays

Shandygaff

Mince Pie

Pipefuls

Plum Pudding

Travels in Philadelphia

Poetry

Songs for a Little House

The Rocking Horse

Hide and Seek

Chimneysmoke

Translations from the Chinese

THE POWDER OF

SYMPATHY

BY

CHRISTOPHER MORLEY

Strange, when you come to think of

it, that of all the countless folk who

have lived before our time on this planet

not one is known in history or in

legend as having died of laughter.

ILLUSTRATED

BY

WALTER JACK DUNCAN

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1923

COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1921, 1922, BY THE NEW YORK EVENING POST, INC.

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY THE OUTLOOK COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

First Edition

DEDICATION

TO FELIX RIESENBERG and FRANKLIN ABBOTT

Dear Felix, dear Frank:—It is a pleasant circumstance

that as one sets about collecting material

for a book, scissoring night after night among scrapbooks

to determine what may or may not be worth

revisiting the glimpses of the press, there comes to

mind with perfect naturalness who should carry the

onus of the dedication. For a book is a frail and

human emanation, and has its own instinctive disposition

toward a certain kind of people. These

Powders of Sympathy I hopefully sprinkle in your direction.

Another good friend warned me seriously, some time

ago, against the danger of being too apologetic in a

preface. For, said he, people always read prefaces

and dedications, even if nought else; if you deprecate,

you at once persuade them to the same attitude. Andvi

to you two, of all readers, I need not explain just how

these pieces were written, day by day, out of the pressure

and hilarity and contention of the mind. I

have made no attempt to conceal their ephemeral origin.

They were almost all written for a newspaper, and

contain many references to journalism. And, if I

may speak my inmost heart, I have had a sincere hope

that they might, in collected form, play some small

part in encouraging the youngest generation of journalists

to be themselves and set things down as they

see them. If these powders have any pharmacal virtue—other

than that of Seidlitz—it is likely to be relative,

not absolute. I mean, it is remarkable that they

should have been written at all: remarkable that any

newspaper should take the pains to offer space to

speculations of this sort. I have not scrupled, on occasion,

to chaff some of the matters newspapers are

supposed to hold sacred. And it is my privilege, by

the way, to say my gratitude and affection to Mr.

Edwin F. Gay, editor of the New York Evening Post,

under whose jurisdiction these were written. With

the generosity of the ideal employer he has encouraged

my ejaculations even when he did not agree with

them.

But a columnist (it is frequently said) is not a real

Newspaper Man: he is only a deboshed Editorial

Writer, a fallen angel abjected from the secure heaven

of anonymity. That is true. The notable increase,

in recent years, of these creatures, has been held to be

a sign that the papers required more scapegoats, or

safety valves through whom readers might blow offvii

their disrespect. And that by posting these innocent

effigies as decoys, the wicked press might go about its

privy misdeeds with more security, and conspire unobserved

with the dangerous minions of Capital (or

Labour, or the Agrarian Bloc).

However that may be, and unsuspecting whether

intended by his scheming employer as a decoy, or a

doormat, or a gargoyle, or a lightning rod (how is he

to know, never having been given instruction of any

sort except to go ahead and write as he pleases?)

the columnist pursues his task and gradually distils

a philosophy of his own out of his duties. Oddly

enough, instead of growing more cautious by reason of

his exposure, he becomes almost dangerously candid.

He knows that if he is wrong he will be set right the

next morning by a stack of letters varying in number

according to the nature of his indiscretion. If he is

wrong about shall and will, he will get five letters of

reproof. If about some nautical nicety, ten letters.

If about the Republican Party, twenty letters. If

about food, thirty-two. If about theology or Ireland,

sixty to seventy. In all cases most of these

letters will be wittier and wiser than anything he

could have composed himself. Surely there is no other

walk of life in which mistakes are so promptly retrovolant.

I have christened these soliloquies after dear old

Sir Kenelm Digby’s famous nostrum, the Powder of

Sympathy. But in spite of its amiable name and

properties that powder was not a talcum. Its basis

was vitriol; and I fear that in some of these prescriptionsviii

I have mixed a few acid crystals. It was either

Lord Bacon or Don Marquis (two deep thinkers whose

maxims are occasionally confounded in my mind)

who told a story about a dog of low degree who

made his reputation by biting a circus lion—thinking

him only another dog, though a large one. Two or

three times herein I have snapped at circus lions; and

probably escaped only because the lion was too proud

to return the indenture. Let it be remembered,

though, that often you may love a man even while you

dispute with him.

But the chief consideration (Frank and Felix) that

seems to emerge from our friendship is that the eager

squabbles of critics and littérateurs are of minor account;

that the great thing is to circulate freely in the

surrounding ocean of inexhaustible humanity, enjoying

with our own eyes and ears the gay and tragic richness

of life. We have had expeditions together, not commemorated

in print, that have been both doctrine

and delight. The incident of the Five-Dollar Bill we

hid in a certain bookshop will recur to your minds; the

day spent in New York Harbour aboard Tug Number

18, and her skipper’s shrewd, endearing sagacity.

Then consider the Mystery of the House on 71st Street;

the smell of Gorgonzola cheese on a North River pier;

the taste of asti spumante; the arguments on the Test

of Courage! These are matters it pleases me to set

down, just as a secret among us. And though I am

(you are aware) no partisan of the telephone, there are

especially two voices I have learned to hear with a

thrill. They say: “Hello! This is Frank;” or “Hello!ix

This is Felix!” And I reply with honest excitement,

for so often those voices are an announcement of Adventure.

Give me a ring soon.

Christopher Morley.

New York City,

November 24, 1922.

x

| |

PAGE |

| An Oxford Symbol |

1 |

| Scapegoats |

7 |

| To a New Yorker a Hundred Years Hence |

12 |

| A Call for the Author |

16 |

| Mr. Pepys’s Christmases |

19 |

| Children as Copy |

25 |

| Hail, Kinsprit! |

30 |

| Round Manhattan Island |

33 |

| The Unknown Citizen |

37 |

| Sir Kenelm Digby |

42 |

| First Impressions of an Amiable Visitor |

58 |

| In Honorem: Martha Washington |

63 |

| According to Hoyle |

67 |

| L. E. W. |

71 |

| Our Extension Course |

75 |

| Some Recipes |

78 |

| Adventures of a Curricular Engineer |

82 |

| Santayana in the Subway |

87 |

| Madonna of the Taxis |

95 |

| Matthew Arnold and Exodontia |

99 |

| Dame Quickly and the Boilroaster |

109 |

| Vacationing with De Quincey |

114 |

| The Spanish Sultry |

132 |

| What Kind of a Dog? |

137xii |

| A Letter from Gissing |

140 |

| July 8, 1822 |

143 |

| Midsummer in Salamis |

148 |

| The Story of Ginger Cubes |

153 |

| The Editor at the Ball Game |

183 |

| The Dame Explores Westchester |

191 |

| The Power and the Glory |

197 |

| Gissing Joins a Country Club |

202 |

| Three Stars on the Back Stoop |

208 |

| A Christmas Card |

213 |

| Symbols and Paradoxes |

218 |

| The Return to Town |

223 |

| Maxims and Minims |

228 |

| Two Reviews |

262 |

| Buddha on the L |

271 |

| Intellectuals and Roughnecks |

279 |

| The Fun of Writing |

288 |

| A Christmas Soliloquy |

291 |

xiii

1

THE POWDER OF

SYMPATHY

AN OXFORD SYMBOL

When in October, 1910, we arrived, in a hansom,

at the sombre gate of New College, Oxford; trod

for the first time through that most impressive of all

college doorways, hidden in its walled and winding

lane; timidly accosted Old Churchill, the whiskered

porter, most dignitarian and genteel of England’s Perfect

Servants; and had our novice glimpse of that noble

Front Quad where the shadow of the battlemented roof

lies patterned across the turf—we were as innocently

hopeful, modestly anxious for learning and eager to do the

right thing in this strange, thrilling environment as ever

any young American who went looking for windmills.

No human being (shrewd observers have remarked) is

more beautifully solemn than the ambitious Young2

American. And, indeed, no writer has ever attempted

to analyze the shimmering tissue of inchoate excitement

and foreboding that fills the spirit of the juvenile

Rhodes Scholar as he first enters his Oxford college.

He arrives with his mind a gentle confusion of hearsay

about Walter Pater, Shelley, boat races, Mr. Gladstone,

Tom Brown, the Scholar Gypsy, and Little Mr. Bouncer.

Kansas City or Sheboygan indeed seem far away

as he crosses those quadrangles looking for his rooms.

But even Oxford, one was perhaps relieved to find,

is not all silver-gray mediæval loveliness. The New

Buildings, to which Churchill directed us, reached

through a tunnel and a bastion in a rampart not much

less than a thousand years elderly, were recognizably

of the Rutherford B. Hayes type of edification. Except

for the look-off upon gray walls, pinnacles, and a green

tracery of gardens, and the calculated absence of plumbing

(a planned method of preserving monastic hardiness

among light-minded youth), the immense cliff of New

Buildings might well have been a lobe of the old Johns

Hopkins or a New York theological seminary. At the

top of four flights we found our pensive citadel. Papered

in blue, upholstered in a gruesome red, with yellow

woodwork, and a fireplace which (we soon learned) was

a potent reeker. It would be cheerful to describe those

two rooms in detail, for we lived in them two years.

But what first caught our eye was a little green pamphlet

lying on the red baize tablecloth. It was lettered

NEW COLLEGE, OXFORD

Information and Regulations

Revised October, 1910

3

Our name was written upon it in ink, and we immediately

sat down to study it. Here, we thought, is our

passkey to this new world of loveliness.

First we found the hours of college chapel. Then,

“All Undergraduates are required to perform Exercises.”

In our simplicity we at first supposed this to

be something in the way of compulsory athletics, but

then discovered it to mean intellectual exercises. Fair

enough, we thought. That is what we came for.

“Undergraduates are required, as a general rule, to

be in College or their Lodgings by 11 p. m., and to

send their Strangers out before that time....

No Undergraduate is allowed to play on any musical

instrument in College rooms except between the hours

of 1 and 9 p. m., unless special leave has been obtained

beforehand from the Dean.... No games are

allowed in the College Quadrangles, and no games except

bowls in the Garden.” Excellent, we meditated;

this is going to be a serious career, full attention to the

delights of the mind and no interruption by corybantic

triflers.

“A Term by residence means pernoctation within

the University for six weeks in Michaelmas or in Hilary

Term, and for three weeks in Easter or in Trinity (or

Act) Term.”... We felt a little uncertain as to

just what time of year Hilary and Act happened. But

we were not halting, just now, over technicalities. We

wanted to imbibe, hastily, the general spirit and flavour

of our new home.... “Every member of the

College is required to deposit Caution-money. Commoners

deposit £30, unless they signify in writing their4

intention to pay their current Battels weekly; in this

case they deposit £10. An undergraduate battling

terminally cannot withdraw part of his Caution-money

and become a weekly battler without the authority of

his parent or guardian.” We at once decided that it

was best to be a weekly battler. Battling, incidentally,

is a word that we believe exists only at Eton and

Oxford; dictionaries tell us that it comes from “an

obsolete verb meaning to fatten.” Sometimes, however,

in dispute with the Junior Bursar, it comes near

its more usual sense. We wondered, in our young

American pride, whether we were a Commoner? We

were pleased to note, however, that the alternative

classification was not a Lord but a Scholar.

We skimmed along through various other instructions.

“A fine of 1s. is charged to the owner of any

bicycle not put away before midnight.” The owner, or

the bicycle, we mused? Never mind—we would soon

learn. Coals and faggots, we noted, were variable in

price. “The charge for a cold bath is 2d., for a hot

4d., inclusive of bath-towel.” The duties of a mysterious

person named as the Bedmaker (but always, in

actual speech, the Scout) were punctually outlined.

But now we found ourself coming to Kitchen, Buttery,

and Store-Room Tariffs. This, evidently, was the

pulse of the machine. With beating heart we read on,

entranced:

| Beer, Mild |

half-pint |

1½ |

| Beer, Mixed |

“ |

2 |

| Beer, Strong |

“ |

2½ |

| Beer, Treble X |

glass |

35 |

| Beer, Lager |

pint |

6 |

| Stout |

half-pint |

2 |

| Cider |

“ |

1½ |

There was something significant, we felt by instinct,

in the fact that Treble X was obtainable only by the

glass. Vital stuff, evidently. Our education was

going to come partly in casks, perhaps? In the Kitchen

Tariff we read, gloatingly, magnificent syllables. Grilled

Sausages and Bacon, commons, 1/2. Devilled Kidneys,

commons, 1/. (A “commons,” we judged, was a

large portion; if you wanted a lesser serving, you ordered

a “small commons.”) Chop with Chips, 11d.

Grilled Bones, 10d. Kedgeree, plain or curried, commons,

9d. (Oh noble kedgeree, so nourishing and inexpensive,

when shall we taste your like again?)

Herrings, Bloaters, Kippers, each 3d. (To think that,

then, we thought the Junior Bursar’s tariff was a bit

steep.) Jelly, Compôte of Fruit, Trifle, Pears and

Cream. Creams ... commons, 6d. “Gentlemen’s

own birds cooked and served ... one

bird, 1/. Two birds, 1/6.”

We went on, with enlarging appreciation, to the

Store Room and Cellar Tariffs: Syphons, Seltzer or

Soda-water, 4½d. Ginger-beer, per bottle, 2d. Cakes:

Genoa, Cambridge, Madeira, Milan, Sandringham,

School, each 1/. Foolscap, per quire, 10d. Quill

Pens, per bundle, 1/6. Cheroots, Cigars, Tobacco,

Cigarettes—and then we found what seemed to be the

crown and cream of our education, LIST OF WINES.

Port, 4/ per bottle. Pale Sherry, 3/. Marsala, 2/.6

Madeira, 4/. Clarets: Bordeaux, 1/6. St. Julien, 2/.

Dessert, 4/. Hock or Rhenish Wine: Marcobrunner,

4/. Niersteiner, 3/. Moselle, 2/6. Burgundy, 2/ and

4/. Pale Brandy, 5/. Scotch Whisky, 4/. Irish

Whisky, 4/. Gin, 3/. Rum, 4/.

It is really too bad to have to compress into a few

paragraphs such a wealth of dreams and memories.

We sat there, with our little pamphlet before us, and

looked out at that great panorama of spires and towers.

We have always believed in falling in with our environment.

The first thing we did that afternoon was to go

out and buy a corkscrew. We have it still—our symbol

of an Oxford education.

The man who did most (I am secretly convinced)

to deprive American literature of some really

fine stuff was Mr. John Wanamaker. It was in his

store, some years ago, that I bought a kind of cot-bed or

couch, which I put in one corner of my workroom and

on which it is my miserable habit to recline when I

might be getting at those magnificent writings I have

planned. Every evening I pile up the cushions and

nestle there with The Gentle Grafter or some detective

story (my favourite relaxation), saying to myself:

“Just ten minutes of loafing”....

But perhaps Messrs. Strawbridge and Clothier (also

of Philadelphia) are equally at fault. When I wake up,

on my Wanamaker divan, it is usually about 2 A. M.

Not too late, even then, for a determined spirit to make8

incision on its tasks. But I find myself moving

towards a very fine white-enamelled icebox which I

bought from Strawbridge and Clothier in 1918. With

that happy faculty of self-persuasion I convince myself

it is only to see whether the pan needs emptying or the

doors latching. But by the time I have scalped a

blackberry pie and eroded a platter of cold macaroni

au gratin, of course work of any sort is out of the

question.

So do the Philistines of this world league themselves

cruelly against the artist, plotting temptation for his

carnal deboshed instincts, joying to see him succumb.

Once the habit of yielding is established, Wanamaker,

Strawbridge and Clothier (dark trio of Norns) have it

their own way. Just as surely as robins will be found

on a new-mown lawn, as certainly as bonfire smoke

veers all round the brush pile to find out the eyes of the

suburban leaf burner, so inevitably do the Divan and

the Icebox exert their cruel dominion over us when we

ought to be pursuing our lovely and impossible dreams.

Wanamaker and Strawbridge and Clothier have blueprints

of the lines of fissure in our frail velleity. As

William Blake might have said:

Let Flesh once get a lead on Spirit,

It’s hard for Soul to reinherit:

When supper’s laid upon a plate

Mind might as well abdicate.

But one of the things I think about, just before I

drop off to sleep on that couch, is My Anthology. Like9

every one else, I have always had an ambition to compile

an anthology of my own; several, in fact. One of

them I call in my own mind The Book of Uncommon

Prayer, and imagine it as a kind of secular breviary,

including many of those beautiful passages in literature

expressing the spirit of supplication. This book, however,

it will take years to collect; it will be entirely

non-sectarian and so truly religious that many people

will be annoyed. People do not care much for books of

real beauty. That anthology edited by Robert Bridges,

for instance—The Spirit of Man—how many readers

have taken the trouble to hunt it out?

But the Uncommon Prayer Book is not the kind

of anthology I have in mind at the moment. What I

need is a book that would boil down the best of all the

books I am fond of and condense it into a little bouillon

cube of wisdom. I have always had in mind the

possibility that I might go travelling, or the house

might burn down, or I might have to sell my library,

or something of that sort. I should like to have the

meat and essence of my favourites in permanent form,

so that wherever I were I could write to the publisher

and get a fresh copy.

This thought came with renewed emphasis the other

day when I was talking to Vachel Lindsay. He was

saying that he had lately been rereading Swinburne, for

the first time in nearly twenty years, and was grieved

to see how the text of the poet had become corrupted in

his memory. He had been misquoting Swinburne for

years and years, he said, and the errors had been growing

more and more firmly into his mind. That led10

me to think, suppose we had only memory to rely on,

how long would the text of anything we loved remain

unblurred? Suppose I were on a desert island and

yearned to solace myself by spouting some of the sonnets

of Shakespeare? How much could I recapture?

Honestly, now, and with no resort to the book on the

shelf at my elbow, let me try an old friend:

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

That alters when it alteration finds

Or bends with the remover to remove.

Oh no, it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken—

Love is the star to every wandering bark

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Then there’s something about a sickle, but I can’t

for the life of me quite get it. Presently I’ll look it up

in the book and see how near I came.

Before opening the Shakespeare, however, let’s have

one more try:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I wail the lack of many a thing I sought

... my dear time’s waste——

And all the rest of that sonnet that I can think of is

something about “death’s dateless night.” A pretty

poor showing. Of course, I should do better on a

desert island: there would be the wide expanse of

shining sand to walk upon, and I could throw myself11

into it with more passion and fury. The secret of remembering

poetry is to get a good barytone start and

obliterate the mind of its current freight of trifles. The

metronomic prosody of the surf would help me, no

doubt, and the placid frondage of the breadfruit trees.

But even so, the recension of Shakespeare’s sonnets

that I would write down upon slips of bark would be a

very corrupt and stumbling text. Favourite lines

would be scrambled into the wrong sonnets, and the

whole thing would be a pitiful miscarriage of memory.

The only sagacious conduct of life is to prepare for

every possible emergency. I have taken out life insurance,

and fire insurance, and burglary insurance, and

automobile insurance. I have always insured myself

against losing my job by taking care not to work too

hard at it, so I wouldn’t miss it too bitterly if it were

suddenly jerked from under me. But what have I

done in the way of Literary Insurance? Suppose, to-morrow,

Adventure should carry me away from these

bookshelves? How pleasant to have a little microcosm

of them that I could take with me! And yet, unless I

can shake off the servitude of those three Philadelphia

mandarins, Wanamaker and Strawbridge and Clothier,

I shall never have it.

When I think of the plays that I would have written

if it weren’t for those three rascals.

12

TO A NEW YORKER A HUNDRED YEARS

HENCE

I wonder, old dear, why my mind has lately been

going out towards you? I wonder if you will ever

read this? They say that wood-pulp paper doesn’t last

long nowadays. But perhaps some of my grandchildren

(with any luck, there should be some born, say

twenty-five years hence) may, in their years of tottering

caducity, come across this scrap of greeting, yellowed

with age. With tenderly cynical waggings of their

faded polls, perhaps they will think back to the tradition

of the quaint vanished creatures who lived

and strove in this city in the year of disgrace, 1921.

Poor old granfer (I can hear them say it, with that

pleasing note of pity), I can just remember how he

used to prate about the heyday of his youth. He

wrote pieces for some paper, didn’t he? Comically

old-fashioned stuff my governor said; some day I13

must go to the library and see if they have any record

of it.

You seem a long way off, this soft September morning,

as I sit here and sneeze (will hay fever still exist in

2021, I wonder?) and listen to the chime of St. Paul’s

ring eleven. Just south of St. Paul’s brown spire the

girders of a great building are going up. Will that

building be there when you read this? What will be

the Olympian skyline of your city? Will poor old

Columbia University be so far downtown that you will

be raising money to move it out of the congested slums

of Morningside? Will you look up, as I do now, to

the great pale shaft of Woolworth; to the golden boy

with wings above Fulton Street? What ships with

new names will come slowly and grandly up your

harbour? What new green spaces will your street

children enjoy? But something of the city we now love

will still abide, I hope, to link our days with yours.

There is little true glory in a city that is always changing.

New stones, new steeples are comely things; but

the human heart clings to places that hold association

and reminiscence. That, I suppose, is the obscure

cause of this queer feeling that impels me to send you

so perishable a message. It is the precious unity of

mankind in all ages, the compassion and love felt by the

understanding spirit for those, its resting kinsmen,

who once were glad and miserable in these same scenes.

It keeps one aware of that marvellous dark river of

human life that runs, down and down uncountably, to

the unexplored seas of Time.

You seem a long way off, I say—and yet it is but an14

instant, and you will be here. Do you know that

feeling, I wonder (so characteristic of our city) that a

man has in an elevator bound (let us say) for the

eighteenth floor? He sees 5 and 6 and 7 flit by, and he

wonders how he can ever live through the interminable

time that must elapse before he will get to his stopping

place and be about the task of the moment. It is only

a few seconds, but his mind can evolve a whole honeycomb

of mysteries in that flash of dragging time. Then

the door slides open before him and that instantaneous

eternity is gone; he is in a new era. So it is with the

race. Even while we try to analyze our present curiosities,

they whiff away and disperse. Before we have

time to turn three times in our chairs, we shall be the

grandparents and you will be smiling at our old-fashioned

sentiments.

But we ask you to look kindly on this our city of

wonder, the city of amazing beauties which is also

(to any man of quick imagination) an actual hell of

haste, din, and dishevelment. Perhaps you by this

time will have brought back something of that serenity,

that reverence for thoughtful things, which our generation

lost—and hardly knew it had lost. But even Hell,

you must admit, has always had its patriots. There is

nothing that hasn’t—which is one of the most charming

oddities of the race.

And how we loved this strange, mad city of ours,

which we knew in our hearts was, to the clear eye of

reason and the pure, sane vision of poetry, a bedlam

of magical impertinence, a blind byway of monstrous

wretchedness. And yet the blacker it seemed to the15

lamp of the spirit, the more we loved it with the troubled

eye of flesh. For humanity, immortal only in misery

and mockery, loves the very tangles in which it has

enmeshed itself: with good reason, for they are the

mark and sign of its being. So you will fail, as we have;

and you will laugh, as we have—but not so heartily,

we insist; no one has ever laughed the way your tremulous

granfers did, old chap! And you will go on about

your business, as we did, and be just as certain that

you and your concerns are the very climax of human

gravity and worth. And will it be any pleasure to you

to know that on a soft September morning a hundred

years ago your affectionate great-grandsire looked

cheerfully out of his lofty kennel window, blew a whiff

of smoke, smiled a trifle gravely upon the familiar

panorama, knew (with that antique shrewdness of his)

a hawk from a handsaw, and then went out to lunch?

But who will write me the book about New York

that I desire? The more I think about it, the

more astonished I am that no one attempts it. I don’t

mean a novel. I would not admit any plot or woven

tissue of story to come between the reader and my royal

heroine, the City herself. Not to be a coward, should I

try to write it myself? It is my secret dream; but,

better, it should be written by some sturdy rogue of a

bachelor, footfree, living in the very heart of the

uproar. Some fellow with a taste and nuance for the

vulgar and vivid; a consort of both parsons and bootleggers;

a Beggar’s Opera kind of rascal. I can think of

three men in this city who have magnificent powers

for such a book; but they are getting perhaps a little

elderly—yes, they are over forty! Ginger must be17

very hot in the mouth of my imagined author. He

must be young (dashed if I don’t think about 32 is the

ideal age to write such a book), but not one of the Extremely

Brilliant Young Men. They are too clever;

and they are not lonely enough. For this is a lonely

job. It’s got to be done solus, slowly, with an eye only

upon the subject. It has got to show the very tremble

and savour of life itself.

The man who will write this book will not necessarily

enjoy it. To get into the secret of Herself he has got

to have a peculiar feeling about her. For years he

must have wrestled with her almost as a personal antagonist.

He must have vowed, since he first saw her

imperial skyline serrated on blue, to make her his own;

a mistress worthy of him, and yet he himself her master.

But he must know, in his inward, that in the end she

triumphs, she tramples down mind and heart and

nerve. Loveliest enemy in the world, implacable victor

over reason and peace and all the quieter sanities of the

spirit, her mad, intolerable beauty crazes or silences

the sensitive mind that woos her. If you think this

is only fine writing and romantic tall-talk, then you

know her only with the eye, not with the imagination.

With good reason, perhaps, her poets have, for the most

part, kept mum. Enough for them to see and cherish

in imagination her little sudden glimpses. A girl,

slender, gayly unconscious of admiration, poises on one

foot at the edge of the subway platform, leaning over to

see if the train is coming. That gallant figure is perhaps

something of a symbol of the city’s own soul.

There must be many who feel about Herself as I do—and,18

more wisely, are tacit. There are many whose

minds have trembled on the steep sills of truth, have

felt that golden tremble of reality almost within touch,

and rather than mar the half-apprehended fable, have

turned troubled away. But there is such poetry in her,

and such fine, glorious animal gusto—why is there not

some determined attempt to set it down, not with

“rhetoricating floscules,” but as it is? Day after day

one comes to the attack; and returning, as the sloping

sunlight and fresh country air flood the dusty red plush

of the homeward smoking-car, readmits the expected

defeat. Here is a target for you, O generation of

snipers. Let us have done with pribbles and prabbles.

Who is the man who will write me the book I crave—that

vulgar, jocund, carnal, beautiful, rueful book!

19

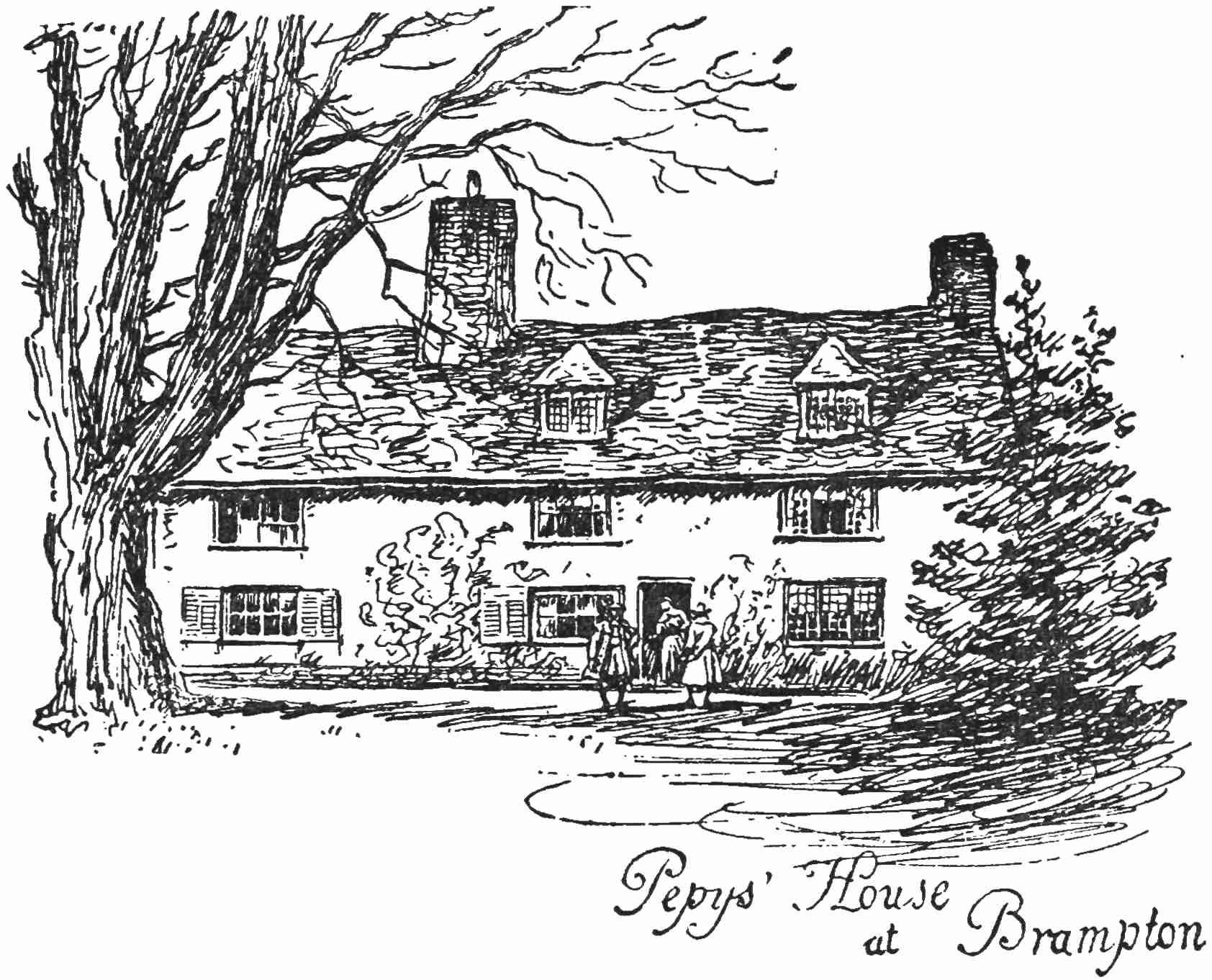

Pepys’ House at Brampton

MR. PEPYS’S CHRISTMASES

Christmas being the topic, suppose we call

upon Mr. Samuel Pepys for testimony. The imperishable

Diarist had as keen a faculty of enjoyment

as any man who ever lived. He wrote one of the

world’s greatest love stories—the story of his own

zealous, inquisitive, jocund love of life. Surely it is not

amiss to inquire what record be left as to the festival

of cheer.

On seven of the nine Christmases in the Diary, Mr.

Pepys went to church—sometimes more than once,

though when he went twice he admits he fell asleep.

The music and the ladies’ finery were undoubtedly part20

of the attraction. “Very great store of fine women

there is in this church, more than I know anywhere else

about us,” is his note for Christmas, 1664. But in that

generously mixed and volatile heart there was a valve

of honest aspiration and piety. One can imagine him

sitting in his pew (on Christmas, 1661, he nearly left the

church in a huff because the verger didn’t come forward

to open the pew door for him), his alert mind

giving close attention to the sermon of his favourite

Mr. Mills, busy with sudden resolutions of virtue and

industry, yet happily conscious of any beauty within

eyeshot.

The giving of presents was not a large part of Christmas

in those days. In 1662 Mr. Gauden gave Pepys

“a great chine of beef and three dozen of tongues,”

but this had its drawbacks. Pepys had to give five

shillings to the man who brought it and also half a

crown to the porters. Drink and food were the important

part of the festival. At Christmas, 1660, Mr.

and Mrs. Pepys, with Tom Pepys as guest, enjoyed

“a good shoulder of mutton and a chicken.” This was

a brave Christmas for Mrs. Pepys—she had “a new

mantle.” We must remember that the fair Elizabeth,

though already married five years, was then only

twenty years old. Not all Mrs. Pepys’s Christmases

were as merry as that, I fear. On Christmas, 1663, she

was troubled by anxious thoughts——

My wife began, I know not whether by design or

chance, to enquire what she should do, if I should by any

accident die, to which I did give her some slight answer,21

but shall make good use of it to bring myself to some

settlement for her sake.

Why haven’t the ingenious life insurance advertisers

made use of this telling bit of copy?

Christmas, 1668, seems to have been poor Mrs.

Pepys’s worst Yule, but perhaps it was only her natural

feminine frivolity that caused the sadness. Samuel

says:

Dinner alone with my wife, who, poor wretch! sat

undressed all day, till 10 at night, altering and lacing of

a noble petticoat.

This noble petticoat was perhaps to be worn at the

play they attended the next day, “Women Pleased.”

What a pleasant Christmas card that scene would

make: Mrs. Pepys sitting, négligée, over the niceties

of her needlework, with Samuel beside her “making

the boy read to me the Life of Julius Cæsar.” But

we do not “get” (as the current phrase is) Mrs. Pepys

at all if we think of her as merely the irresponsible girl.

For, at Christmas, ’66, we read:

Lay pretty long in bed, and then rose, leaving my

wife desirous to sleep, having sat up till 4 this morning

seeing her maids make mince-pies.

Ah, we have no such mince pies nowadays. Mrs.

Pepys’s mince pies were evidently worthy the tradition

of that magnificent delicacy, for at Christmas, 1662,22

when Elizabeth was ill abed, Samuel records—with

an evident touch of regret—that he had to “send

abroad” for one.

* * * * *

Which brings us back to the Christmas viands. In

1662, besides the mince pie from abroad, he “dined

by my wife’s bedside with great content, having a

mess of brave plum-porridge and a roasted pullet.”

We are tempted to think 1666 was Samuel’s best

Christmas. Parson Mills made a good sermon.

“Then home and dined well on some good ribs of beef

roasted and mince pies; only my wife, brother, and

Barker, and plenty of good wine of my own, and my

heart full of true joy.” After dinner they had a little

music; and he spent the evening making a catalogue of

his books (“reducing the names of all my books to an

alphabet”), which is probably the happiest task a man

of Pepys’s temperament could enjoy.

Christmas Eve, 1667, was evidently a cheerful evening.

Mr. Pepys stopped in at the Rose Tavern for

some “burnt wine”; walked round the city in the moonlight,

and homeward early in the morning in such content

that “I dropped money in five or six places, which

I was the willinger to do, it being Christmas Day, and

so home, and there find my wife in bed, and Jane and

the maid making pies.” The evening of that Christmas

Mrs. Pepys read aloud to him—The History of the

Drummer of Mr. Mompesson, apparently a kind of

contemporary Phillips Oppenheim—“a strange story of

spies, and worth reading, indeed.” It was only in 1660

that the Christmas cheer was a little too much for our23

Diarist. December 27, 1660, “about the middle of

the night I was very ill—I think with eating and drinking

too much—and so I was forced to call the maid,

who pleased my wife and I in her running up and down

so innocently in her smock.”

* * * * *

It is painful to this tracker of Mr. Pepys’s vestiges to

note that on Christmas Day, 1662, Bishop Morley at the

Chapel Royal “made but a poor sermon.” The

Bishop apparently rebuked the levity of the Court.

“It was worth observing how far they are come from

taking the reprehensions of a Bishop seriously, that

they all laugh in the chapel when he reflected on their

ill-actions and courses. He did much press us to joy

in these public days of joy, and to hospitality; but one

that stood by whispered in my ear that the Bishop do

not spend one groat to the poor himself.” In 1665

we fear that Samuel indulged himself in church with

some rather cynical thoughts:

Saw a wedding in the church, and the young people

so merry one with another; and strange to see what delight

we married people have to see these poor fools

decoyed into our condition, every man and woman gazing

and smiling at them.

One could continue for some space recounting the

eupeptic Pepys in his Christmas merriments—so large

an edifice of pleasing conjecture can be built upon even

his slightest notes. One observes, for instance, that on

December 27, 1664, when “my wife and all her folks”

came “to make Christmas gambols,” Samuel left the24

party and went to bed. This was very different from

his usual habit when there was fun going. He was

annoyed also that on this occasion his wife revelled all

night, not coming to bed until 8 the next morning,

“which vexed me a little, but I believe there was no

hurt in it at all, but only mirth.”

So we take leave of the Christmases of the Pepyses;

1668 is the last one recorded—the time when Elizabeth

stayed at home all day altering her petticoat. After

supper, the boy played some music on the lute, and

Samuel’s mind was “in mighty content.” Let us

think kindly of the good fellow; and not forget that he

coined one of the enduring phrases of English literature—a

phrase that is no such ineffective summary of all the

lives of men—And so to bed.

Titania said: “You haven’t written a poem about

the baby yet.”

It is quite true. She is now thirteen months old,

and has not yet had a poem written about her. Titania

considers this deplorable. The first baby was hardly a

week old before all sorts of literary studies were packing

the mails, speeding to such editors as were known to

be prompt pay. (I hope, indeed I hope, you never

saw that astounding essay—published anonymously in

Every Week which expired soon after—called “The

Expectant Father,” which was written when the poor

urchin was some twenty-four hours old. It was his

first attempt to earn money for his parent. If any26

child ever paid his own hospital bills—C. O. D., as you

might say—it was he. I believe in bringing up my

children to be self-supporting.)

And the second baby was only three weeks old when

the first poem about her was written.

But here is this third morsel, thirteen months old

and no poem yet. Titania, I say, considers this a kind

of insult to the innocent babe. No, not at all, my dear.

I admit that it would be very helpful if H. (I will call

her that, for baby is a word that cannot be repeated in

print very often without all hands growing maudlin;

and I don’t like to use her own name, which seems too

personal; just remember, then, that H. stands for a

small brown-eyed creature who is still listed in the

Bureau of Records of the Department of Health [certificate

No. 43515, anno 1920] as Female Morley, because

when the birth was registered by the doctor her name

had not been decided, and ever since then I have been

too busy to go round to call on Dr. Copeland, the Health

Commissioner, and ask him to have her more specifically

enrolled)—I admit it would be very helpful if she

were to turn to and lend a hand in paying the coal bill

by having some verses written about herself. I have

looked at her with admiration every day for these thirteen

months, trying, as one might say, to get some

angle on her that would lead to a poem. She does not

seem very angular.

I insist that my not having written a poem about her

is really very creditable. Titania seems to think that

it implies my having become, in some sense, blasé

about children. Again, not so, not so at all. I must27

confess that in my enthusiasm I rather made use of the

two older urchins as copy. But H., droll infant that

she is, is too subtle for me. I’ll come to that in a

minute.

I talked all this matter over (being of a cautious turn,

and fond of getting experienced advice) with two eminent

author-parents—Mr. Tom Masson and Mr. Tom

Daly—long ago, before Titania and I began putting on

heirs. Both these gentlemen have made a lot of use of

their children in earning, or at any rate gaining, a living.

Their advices coincided. I myself was worried,

but Mr. Tom Masson insisted that there was nothing

like having offspring as a source of copy; he said that he

would pay ten cents a word, in Life, for anything

about the then shortly arriving urchin. (He said it

would be fifteen cents a word if it was a girl, because

girls cost you so much more later on. He has had experience

in that matter, I believe.) Mr. Tom Daly,

who has run rather to boys, said very much the same

thing; but he was not in a position to buy my stuff, so

I paid less attention to him.

But to get back to H. There never was a more enchanting

infant. Mr. Walter de la Mare, who is also

an authority, has written me delightful letters about her,

although he has never seen her. But even a prose

letter from a poet like Mr. de la Mare is more valuable,

I think, than an actual poem from most other poets, so

darling H. cannot say she has been neglected. But she

is much too delicious for me to be able to sit down easily

and write something that would do her justice. The

night before she was born her mother and I did two28

things. We went to Huyler’s for chocolate ice-cream

soda, and we read aloud Bernard Shaw’s autobiography,

which is printed in Frank Harris’s Contemporary

Portraits. I dislike to bring Mr. Harris into this,

for certainly I can think of no one who has less in common

with H., that celestial nugget. But I have to tell

the truth, don’t I? Mr. Harris wrote an essay about

Shaw; and Shaw, feeling that it was not adequate,

wrote a really amusing sketch to show how Harris

should have done it. Well, there is something symbolic

about this, for H. is as sweet as anything Huyler ever

compounded; and she is even more enigmatic than

Shaw. (I can see now it should have been Page and

Shaw instead of Huyler.)

But I feel that pretty soon I shall be writing a poem

about her. I have felt it coming for some time. But it

has got to come; I am not going to bring it. That shows

how I have matured by associating with H. Sometimes

I wish I could hire a really great poet to write about her.

Swinburne might do for the rough draft. “Oh, what

a bee-yootiful babby!” he used to cry when he saw them

in their prams up at Putney—so, I think, Max Beerbohm

describes. But I should want to have his rough

draft polished and refined by someone else. I can

only think of Mr. Walter de la Mare. He alone has

just the right insight. For babies thirteen months old—the

best age of all—must not be treated condescendingly,

nor fulsomely, nor adoringly, nor sugarishly.

William Blake, if left alone in the room with H., would

have understood her. What an infant, I give you my

word! Living with children is largely a contest of endurance.29

It is a question of which one can tire the other

out first. (This is a great secret; never before made

plain.) Start in early in the morning, and take things

with a rush. If you are strong, austere, resolute, you

may be able to wear them down and exhaust them by

dusk. If you can do so, without prostrating yourself,

then you may get them to bed safely and have a few

hours of cheerful lassitude. But take every possible

advantage. Let them run and frolic, yourself sitting

down as much as you can. Favour yourself, and snatch

a little rest while they are not looking. Even so, the

chances are you will crack first.

This applies to older children; after they gain the

use of their limbs and minds. But H. has not reached

that harrowing stage. Placable, wise, serene, she sits

in her crib. She has four teeth (beauties). To hear

her cry is so rare that I hardly know what her voice of

sorrow sounds like. Sometimes, for an instant, she

looks a little frightened. Then I like her best, for I

know she is human, and has in her the general capsule

of frailty.

You may be quite sure of one thing, I shall never

print that poem unless I feel that it comes somewhere

near doing her justice.

The keenest pleasure in life, of course, is to find a

Kindred Spirit—one whose mind glows and teeters

with delight at the same queer things that rouse us to

excitement. We have just found one, and yet we shall

never know him, except by his address, which is Y.

1926, the Times, E. C. 4, London. For we are much too

busy to write to any one, even to a Kindred Spirit.

We will tell you why we feel sure he is a Kindred

Spirit; but in parenthesis, it was Mr. Pearsall Smith

who lamented the fact that the English language contains

no satisfactory word for “a person who is enthusiastic

about the same things that you are enthusiastic

about.” It is too grossly clumsy to say fellow-fan

or co-enthusiast; so Mr. Smith, a philologist of charming

finesse (have you read his little book The English

Language published by Henry Holt?) boldly proposed

to fill the vacancy by coining the word milver. This, he31

said, would be useful to poets, since there is no rhyme

in English for silver.

The word milver, alas, leaves us cool, in spite of its

usefulness as a rhyme. It does not strike down in the

great subsoil of the language—the dark deep skein of

inherited word-roots from which our present meanings

blossom and put forth. We suggest—without much

thought—a mere contraction. How would kinsprit do?

We rather like the look of it; it has a droll, benign,

elvish appearance as we put it down. A couplet occurs

to us—

They pledged their bond with joyful oath—

A kinsprit passion knit them both.

That shows you it could be used as an adjective as well.

Come, now, if we all pull together very likely we can

get Messrs. Merriam to put it in the next edition of

Webster:

Kinsprit, n and a. (orig. obscure: perh. contracted

from kin[dred] sprit[e])—A fellow-enthusiast, one

impassioned with the same zeal or hobby or enthusiasm.

The reason why we know that Y. 1926 is a kinsprit

is in the following notice in the Personal column of the

London Times:

Lost in Taxi last week, SMALL PORTFOLIO containing

colour diagrams and newspaper print of Lamb’s portrait

of Lytton Strachey. Finder rewarded. Y. 1926,

The Times, E. C. 4.

32

Well, well, we say to ourself: then there is one other

person in the world who felt just as we did about that

gloriously entertaining portrait of Mr. Strachey, and

who carried it about with him just as we did ours,

clipped from the Manchester Guardian. But we are

luckier than poor Y. 1926, because in an access of enthusiasm

we wrote to Mr. Henry Lamb, the artist, and

begged from him a photo-print of the picture, which is

in front of us now. We think that Mr. Alfred Harcourt,

Mr. Strachey’s publisher, should implore the loan of

the canvas for a few months, and have it exhibited in a

Fifth Avenue window where we could all have a good

look at it.

We are consumed with curiosity to know more about

Y. 1926—where he was going in that taxi, and what the

colour diagrams were (they sound interesting) and

what are his general comments on life?

33

ROUND MANHATTAN ISLAND

We were talking with an American who had just

come back after living several years in Europe.

He expressed with some dismay his resensitized impression

of the furious ugliness and clamour of American

life; the ghastly wastes of rubbish and kindling-wood

suburbs fringing our cities; and suggested that the

trouble is that we have little or no instinctive sense of

beauty.

To which we replied that perhaps the truth of it is

that the American temperament is more likely to see

opportunities for beauty in large things than in small.

But we were both talking bosh. Only an extraordinarily

keen and trained philosophic perception—e. g.,

a Santayana—can discuss such matters without gibbering.

A recent book on young American intellectualism

recurs to us as an example of the futility of undigested34

prattle about æsthetics. Even the word æsthetics

itself has come to have a windy savour by reason of

much sophomore talk.

But, though we have laid by our own copy of that

particular book as a permanent curio in the realm of

well-meant gravity, its author was obeying a sound and

praisable instinct in trying to think about these things—beauty,

imagination, the mind’s freedom to create, the

meaning of our civilization. We are all compelled to

such an attempt: shallow, unversed, clumsily intuitive,

we grope into them because we are sincerely hungry to

understand. The same wise, brave, gracious spirit

that moved Mr. Montague to write his exquisite book

Disenchantment is tremulously and tentatively alert

in thousands of less competent minds. And we, for

our own part, grow just a little impatient with those

who are quick to damn this wildly energetic and thronging

civilization because it shows a poverty of settled,

tranquil loveliness. We look out of our window into

this morning where Mrs. Meynell’s “wind of clear

weather” tosses the Post Office flags and the rooftop

plumes of steam; we see the Woolworth pinnacle hanging

over our head—and ask, is it possible that this great

spectacle breathes from her towers only the last enchantments

of a muddled age?

Aristotle remarked that “the flute is not an instrument

which has a good moral effect; it is too exciting.”

And very likely New York civilization falls under the

same reproach. But even if it is all madness, what a

gallant raving! You cannot see the beauty in anything

until you love it for its own sake. Take the sightseeing35

boat round Manhattan if you want to get a mental

synthesis of this strangest of islands. From a point in

the East River off Coenties Slip you will see those

cubed terraces of building rising up and upward, shelves

and ledges of rectangular perspective like the heaven of

a modernist painter. Nor do we deny the madness

and horror. Farther up the river you will see the

ragged edges of the city, scows loading their tons of

jetsam and street scourings, wizened piers, grassless

parks, all the pitiful makeshift aquatics of the Harlem

region. And yet, all along that gruesome foreshore,

boys—and girls, too—bathing gayly in the scum-water,

flying ragged kites from pier-bollards, merry and

naked on slides of rock or piles of barrels. Only on the

three grim islands of Blackwell, Ward, and Randall will

you see any touch of beauty. There, grass and trees

and beds of canna and salvia (the two great institutional

flowers) to soothe the criminal and the mad. When

your mind or your morals or your muscles give way,

the city will allow you a pleasant haven of greenery

and air. It is odd to see the broad grounds of the

Children’s Hospital—on Randalls Island, is it?—with

no child in sight; but across the river the vile and

scabby shore is thick with them. And the bases of

the Harlem swing-bridges, never trod by any one, are

carefully grassed and flowered.

So the history of every modern city consists of a

painful, slow retracing of its errors, an attempt to undo

painfully and at vast expense the slattern stupidities

it has allowed to accumulate. But to see only these

paradoxes and uglinesses is to see less than the whole.36

He cannot have lived very long or thoughtfully with

humanity for neighbour who does not ruefully accept

greeds and blindnesses as part of its ineradicable habit.

It takes a strong stretch of the imagination to grasp

this island entire; to see, even in its very squalors and

heedlessnesses, an integral portion of its brave teeming

life. You must love it for what it is before you have

a right to love it for what it may be. We have never

been able to think this thing out, but there seems to us

to be some vital essence, some miraculous tremor of

human energy and folly in the whole scene that condones

and justifies the ugliness. It is queer, but the

hideous back-lots of the city do not trouble us so

greatly: we have a feeling that they are on their way

towards being something else. We do not praise them,

but we feel in an obscure way they are part of the picture.

Zealous passion and movement always present,

to the eye of dispassion, aspects either grotesque or

terrible, according to that eye’s focus. In this ugly

hurly-burly we feel daily (though we cannot define it)

that there is a beauty so overriding that it does not

depend on beautiful particulars. And, to feel that

beauty fully, one must discard all hankerings to improve

humanity, or to preach to it, or even understand it—simply

(as Uncle Remus said) “make a great ’miration”—accept

it as it thrillingly is, and admire.

We shall never forget being in Washington

when the great celebration was held in honour of

the Unknown Citizen.

The day was proclaimed a National Fête. On that

day the Unknown Citizen—chosen after long investigation

by a secret committee sworn to silence—arrived

at the Union Station. He and his wife had been

quietly lured away from their home on a plausible pretext

and then kidnapped into a gaudy special train,

where everything had been explained to them. Halts

had been made at big cities en route for the crowds to

pay homage.

It would take too long to describe the clever selective38

process by which the Citizen had been chosen. Suffice

it to say that he was a typical homo Americanus—a

worthy and slightly battered creature, who had raised

a family of four children and plugged along at his job

and paid his taxes and cranked his flivver and set up a

radio on the roof and planted sunflowers in the back

yard and lent his wife a hand at the washing and frequently

mended the kitchen stove-pipe. He had never

broken open the china pigs containing the children’s

money.

We saw him arrive at the great station in Washington.

He was strangely troubled and anxious, a bit

incredulous, too, believing this was all some sort of put-up

job. Also, somewhere on the train he had lost one

of his elastic sleeve-suspenders, and one cuff kept on

falling round his wrist. He walked uneasily along the

red velvet carpet and was greeted by President Harding

and the Ambassadors of Foreign Powers. Mr. Sousa’s

band was there, and struck up an uproarious anthem

composed for the occasion. The tactful committee of

Daughters of the American Bourgeoisie had made all

arrangements and taken all possible precautions. It

had been feared that perhaps the Citizen’s Wife might

be overcome, and an ambulance was waiting behind

potted palms in case of any emergency. But it is always

the unexpected that happens. It was Senator

Lodge, who had been appointed to read the telegrams

from prominent people, who swooned. President

Harding, with kindly readiness, stepped into the breach.

As they were handed to him he read aloud the messages

from M. Clemenceau, Mr. Lloyd George, William Allen39

White, Samuel Gompers, Dr. Frank Crane, President

Ebert, Paul Poiret, M. Paderewski, M. Venizelos, the

Archbishop of Canterbury, and Isaac Marcosson. Mr. Harding

then spoke in the most friendly and charming

way, appraising the value of preserved nationality, the

solid virtue of the Founding Fathers, and the services

of the Unknown Citizen to his country.

For a moment there was an awkward pause, but the

Citizen’s Wife, evidently a strong-minded woman,

nudged him sharply, and the Citizen tottered forward.

Fortunately some New York newspaper men had been

on the train with him, and had written a little speech

for him to deliver. He read it, a bit tremulously. It

stated that he was aware this tribute was not meant for

him personally, but for the great body of middle-class

citizenship he had been chosen to represent. There

was great speculation in the audience as to what part

of the country the Citizen came from: his accent was

perhaps a trifle Hoosierish, but wiseacres insisted that

his general fixings were plainly Sears-Roebuck and not

identifiable with any section.

Accompanied by a troop of cavalry and the national

colours, the Unknown Citizen was taken to the Capitol,

where Congress, convened in joint session, awaited to

do him honour. He was presented to the great body

by Senator Lodge, who had now completely recovered.

After being introduced, the Citizen stammered a few

words of embarrassment. During the buffet lunch in

the lobbies, however, he began to pluck up heart, for he

found the Congressmen very human. He even ventured

to express, very politely, a few sentiments about40

the bonus, the tariff, the income tax, the shipping subsidy,

and the coal strike. Gathering confidence, he

might have grown almost eloquent over these topics,

but the Senatorial committee, foreseeing trouble,

hastened him along to see the gifts that had been sent

from all over the world. They were all laid out for inspection.

Henry Ford had sent a new sedan, with a

self-starter and the arms of the United States gilded on

the door. William Randolph Hearst had sent a bound

volume of Arthur Brisbane’s editorials. The Prince of

Wales, perhaps misunderstanding the exact nature of

the ceremony, had sent a solid gold punch bowl engraved

Dieu et Mon Drought. The Premier of New

Zealand had sent a live kangaroo. The Bailiff of Angora

had sent a large silky goat. Mayor Hylan had

sent a signed photograph of himself wearing overalls.

The Shipping Board had sent a silver flask. But we

have not space for the full list of presents.

Tea was served at the White House. All the corps

diplomatique were there, and were presented to the

Citizen and his Wife. It was a great afternoon. The

Marine Band played in the garden; Senator Borah and

William Jennings Bryan, beginning to see a sort of

prickly heat burn out upon the Unknown Citizen’s forehead,

tactfully played a tennis match to keep the crowd

in good humour. Laddie Boy, wagging his tail vigorously,

kept at the Unknown Citizen’s heels and did

much to cheer him. The Unknown Citizen liked Mr.

Harding greatly and found him easy to talk to; but

some of the Special Representatives from abroad, such

as Mr. Balfour and M. Tardieu, he found difficult.

41

The monument in Potomac Park was dedicated at

sunset. After that the committee on Savoir Faire,

observing the wilted collar of the Unknown Citizen,

thought it the truest courtesy to let him escape. We

ourself managed to follow him through the crowds. He

and his wife looked nervously over their shoulders now

and then, but they had shaken off pursuit. At a little

stationery store they bought some postcards. Then they

went to the movies.

Sir Kenelm Digby, of whose acquaintance all his contemporaries

seem to have been ambitious.

—Dr. Johnson, Life of Cowley.

Prohibition, I dare say, is going to make

fashionable the private compilation of just such delightful

works as The Closet of the Eminently Learned

Sir Kenelme Digbie Opened; London, at the Star in

Little Britain, 1669. Sir Kenelm, “the friend of kings

and the special friend of queens,” crony of such diverse

spirits as Bacon, Ben Jonson, and Oliver Cromwell,

kept this notebook of his jocund experiments in home

brewing and cookery. Just as nowadays a man will43

jot down the formula of some friend’s shining success in

the matter of domestic chianti, so did the admirable

Kenelm record “Sir Thomas Gower’s Metheglin for

Health,” or “My Lord Hollis’ Hydromel,” or “Sir

John Colladon’s Oat-Meal Pap,” or “My Lady Diana

Porter’s Scotch Collops;” and adding, of course, his

own particular triumphs—e. g., “Hydromel as I Made

it Weak for the Queen Mother,” “A Good Quaking

Bag-Pudding,” and “To Fatten Young Chickens in a

Wonderful Degree.” Sir Kenelm’s official duty at the

court of Charles the First was Gentleman of the Bed-chamber;

but if I had been Charles, I should have transferred

him to the Pantry.

The Closet Opened (which was not published until

after Sir Kenelm’s death; he was born 1603, died 1665)

is the kind of book delightfully apt for the sad, sagacious,

and solitary, for one cannot spend an hour in it

without deriving a lively sense of the opulence and

soundness of life. The affectionate attention Sir

Kenelm pays the raisin makes him seem almost a Volsteadian

figure: in his pages that excellent and powerful

fruity capsule plays, perhaps for the first time in

history, a heroic and leading rôle. Consider this:

TO MAKE ALE DRINK QUICK

When small Ale hath wrought sufficiently, draw into

bottles; but first put into every bottle twelve good

raisins of the Sun split and stoned. Then stop up the

bottle close and set it in sand (gravel) or a cold dry

Cellar. After a while this will drink exceedingly quick

and pleasant. Likewise take six Wheat-corns, and44

bruise them, and put into a bottle of Ale; it will make it

exceeding quick and stronger.

Kenelm was not only a good eater; he was a devilish

good writer. The fine lusty root of English prose was

in him. If this is not true literature, we know it not:

ANOTHER CLOUTED CREAM

Milk your Cows in the evening about the ordinary

hour, and fill with it a little Kettle about three quarters

full, so that there may be happily two or three Gallons

of Milk. Let this stand thus five or six hours. About

twelve a Clock at night kindle a good fire of Charcoal,

and set a large Trivet over it. When the fire is very

clear and quick, and free from all smoak, set your Kettle

of Milk over it upon the Trivet, and have in a pot by a

quart of good Cream ready to put in at the due time;

which must be, when you see the Milk begin to boil

simpringly. Then pour in the Cream in a little stream

and low, upon a place, where you see the milk simper....

To simper—a word of sheer genius! There are many

such in his recipes.

We find the raisin again at work in his directions:

TO MAKE EXCELLENT MEATHE

To every quart of Honey, take four quarts of water.

Put your water in a clean Kettle over the fire, and with

a stick take the just measure, how high the water

cometh, making a notch, where the superficies toucheth

the stick. As soon as the water is warm, put in your

Honey, and let it boil, skiming it always, till it be very

clean; Then put to every Gallon of water, one pound

of the best Blew-raisins of the Sun, first clean picked

from the stalks, and clean washed. Let them remain45

in the boiling Liquor, till they be throughly swollen and

soft; Then take them out, and put them into a Hair-bag,

and strain all the juice and pulp and substance from

them in an Apothecaries Press; which put back into

your liquor, and let it boil, till it be consumed just to

the notch you took at first, for the measure of your water

alone. Then let your Liquor run through a Hair-strainer

into an empty Woodden-fat, which must stand

endwise, with the head of the upper-end out; and there

let it remain till the next day, that the liquor be quite

cold. Then Tun it up into a good Barrel, not filled

quite full, and let the bung remain open for six weeks.

Then stop it up close, and drink not of it till after nine

months.

This Meathe is singularly good for a Consumption,

Stone, Gravel, Weak-sight, and many more things. A

Chief Burgomaster of Antwerpe, used for many years

to drink no other drink but this; at Meals and all times,

even for pledging of healths. And though He were an

old man he was of an extraordinary vigor every way,

and had every year a Child, had always a great appetite

and good digestion; and yet was not fat.

One of good Sir Kenelm’s most famous instructions,

which has become fairly well-known, does honour not

only to his delicate taste but also to his religious devotion.

It is his advice on the brewing of tea—“The

water is to remain upon it no longer than whiles you

can say the Miserere Psalm very leisurely.” This advice

occurs in the recipe

TEA WITH EGGS

The Jesuite that came from China, Ann. 1664, told

Mr. Waller, That there they use sometimes in this manner.

To near a pint of the infusion, take two yolks of46

new laid-eggs, and beat them very well with as much

fine Sugar as is sufficient for this quantity of Liquor;

when they are very well incorporated, pour your Tea

upon the Eggs and Sugar, and stir them well together.

So drink it hot. This is when you come home from attending

business abroad, and are very hungry, and yet

have not conveniency to eat presently a competent

meal. This presently discusseth and satisfieth all rawness

and indigence of the stomack, flyeth suddainly

over the whole body and into the veins, and strengthenth

exceedingly and preserves one a good while from

necessity of eating. Mr. Waller findeth all those effects

of it thus with Eggs. In these parts, He saith, we let

the hot water remain too long soaking upon the Tea,

which makes it extract into itself the earthy parts of

the herb. The water is to remain upon it no longer

than whiles you can say the Miserere Psalm very

leisurely. Thus you have only the spiritual parts of

the Tea, which is much more active, penetrative, and

friendly to nature.

Sometimes, it is true, one suspects Sir Kenelm of a

tendency to gild the lily. In the matter of perfuming

his tobacco, this was his procedure:—

Take Balm of Peru half an ounce, seven or eight

Drops of Oyl of Cinamon, Oyl of Cloves five drops,

Oyl of Nutmegs, of Thyme, of Lavender, of Fennel, of

Aniseeds (all drawn by distillation) of each a like

quantity, or more or less as you like the Odour, and

would have it strongest; incorporate with these half a

dram of Ambergrease; make all these into a Paste;

which keep in a Box; when you have fill’d your Pipe

of Tobacco, put upon it about the bigness of a Pin’s

Head of this Composition.

It will make the Smoak most pleasantly odoriferous,47

both to the Takers, and to them that come into the

Room; and ones Breath will be sweet all the day after.

It also comforts the Head and Brains.

It is a great temptation to go on quoting these seductive

formulæ. I feel sure that my tenderer readers

would relish instructions for the Beautifying Water or

Precious Cosmetick,—for the secret of which ladies

of high degree pursued Sir Kenelm all over Europe.

(He does not include in the Closet any details of the

Viper Wine for the Complection which was said to have

caused the death of Lady Digby—a rather painful

scandal at the time.) But I fear to trespass on your

patience. Let me only add that the ambition of the

Three Hours for Lunch Club has long been to hold a

DIGBY DINNER, at which all the dishes will be prepared

as nearly as possible according to Sir Kenelm’s prescriptions.

The project offers various perplexities, and

might even have to be consummated at sea, beyond

the hundred-fathom curve. But if it ever comes to

pass, the following menu, carefully chosen from Sir

Kenelm’s delicacies, seems to me promising:—

Portugal Broth, As It Was Made for the Queen

Sack with Clove Gillyflowers

Sucket of Mallow Stalks

A Herring Pye

A Smoothening Quiddany of Quinces

My Lady Diana Porter’s Scotch Collops

Mead, from the Muscovian Ambassador’s Steward

The Queen Mother’s Hotchpot of Mutton

Pease of the Seedy Buds of Tulips

Boiled Rice in a Pipkin48

Marmulate of Pippins

Dr. Bacon’s Julep of Conserve of Red Roses

Excellent Spinage Pasties

Pleasant Cordial Tablets, Which Strengthen Nature

Small Ale for the Stone

A Nourishing Hachy

Plague Water

Marrow Sops with Wine

My Lord of Denbigh’s Almond Marchpane

Sallet of Cold Capon Rosted

My Lady of Portland’s Minced Pyes

The Liquor of Life

A Quaking Bag-Pudding

Metheglin for the Colic

But I must not mislead you into thinking that Sir

Kenelm was merely a convivial trencherman. His

biography as related in the Encyclopædia Britannica

is as diverting as a novel—more so than many. Infant

prodigy, irresistible wooer, privateer, scientist, religious

controversialist, astrologer, and a glorious talker,

he made a profound impression on the life of his time.

But, as so often happens, his name has been carried

down to posterity not by the strange laborious treatise

he regarded as his opus maximum, but by his chance

association with one of the great books of all time.

When Digby was under honorable confinement (as a

“Popish recusant”) at Winchester House, Southwark, in

1642, he was busy there with chemical experiment

and the MS. of his Of Bodies and Mans Soul (of which

more in a moment). Apparently they treated political

prisoners with more indulgence in those days. One

evening he received a letter from his friend the Earl49

of Dorset, urging him to read a book that was making

a stir among the intellectuals. One may think it was

perhaps a trifle niggardly of Dorset merely to have

recommended the book. To a friend in jail, surely he

might (and it was just before Christmas) have sent a

copy as a present. But the liberality of the Earl is not

to be called in question: he had made Sir Kenelm at

least one startlingly gracious gift—viz. Lady Digby

herself, previously Dorset’s mistress. This oddly

amusing story, or gossip, may be pursued in Aubrey’s

Brief Lives, a fascinating book (published by the Oxford

Press)—a sort of Social Register of seventeenth century

England.

“Late as it was” when Sir Kenelm received the letter

from his benefactor and colleague, he sent out at once

(mark the high spirit of the true inquirer; also the sagacity

of seventeenth century booksellers, who kept open at

night)—

To let you see how the little needle of my

Soul is throughly touched at the great Loadstone

of yours, and followeth suddenly and strongly,

which way soever you becken it.... I sent

presently (as late as it was) to Pauls Church-yard,

for this Favourite of yours, Religio Medici: which

found me in a condition fit to receive a Blessing; for

I was newly gotten into my Bed. This good

natur’d creature I could easily perswade to be my

Bed-fellow, and to wake with me, as long as I had

any edge to entertain my self with the delights I

sucked from so noble a conversation.

Rarely have the pleasures of reading in bed had such

durable result. The following day he spent in pouring50

out a long, spirited and powerful letter to Dorset (75

printed pages) which has become famous as Observations

upon Religio Medici, and a few years later was

included as a supplement to that book—where it still

remains in most editions. In this tumbling out of

his honourable meditations and excitements, Sir Kenelm

took issue pretty smartly with Dr. Browne on a number

of points, particularly in regard to his own special hobby

of Immortality. He, just as much as the Norwich

physician, loved to lose himself in an Altitudo; but in

some cloudlands of airy doctrine Browne seemed to

him too precise. “The dint of Wit,” Digby remarked

felicitously of some theological impasse, “is not forcible

enough to dissect such tough matter.”

These Observations are of more than casual importance.

Dorset, apparently, took steps (unknown to

Digby) to have them published; and report of this coming

blast roused Browne to protest courteously against