JAN ARNOLFINI AND JEANNE DE CHENANY.

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The brothers Van Eyck, by P. G. Konody

Title: The brothers Van Eyck

Author: P. G. Konody

Release Date: November 6, 2022 [eBook #69306]

Language: English

Produced by: Al Haines

JAN ARNOLFINI AND JEANNE DE CHENANY.

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

Bell's Miniature Series of Painters

BY

P. G. KONODY

LONDON

GEORGE BELL & SONS

1907

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE TIMES OF THE BROTHERS VAN EYCK

LIST OF WORKS, CATALOGUED ACCORDING TO LOCALITY

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

JAN ARNOLFINI AND JEANNE DE CHENANY

(National Gallery) - - - Frontispiece

By Jan van Eyck.

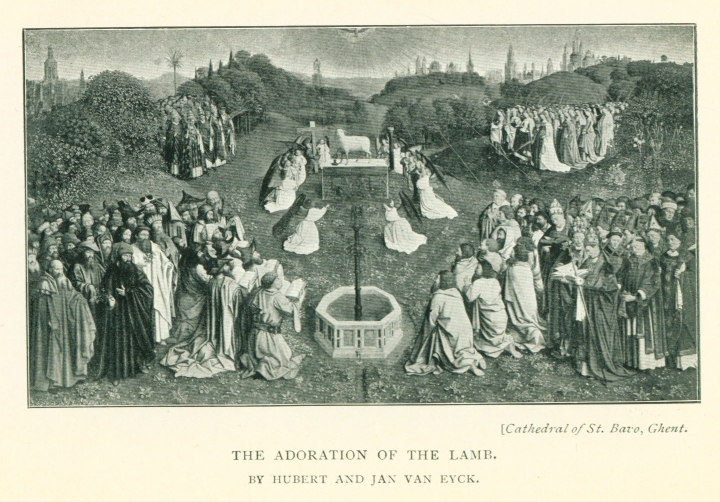

THE ADORATION OF THE LAMB

(Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent)

By Hubert and Jan van Eyck.

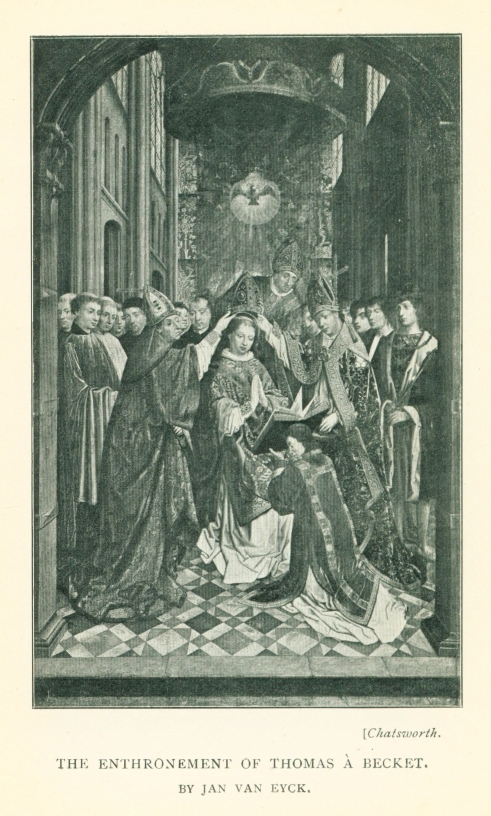

THE ENTHRONEMENT OF THOMAS À BECKET

(Chatsworth)

By Jan van Eyck.

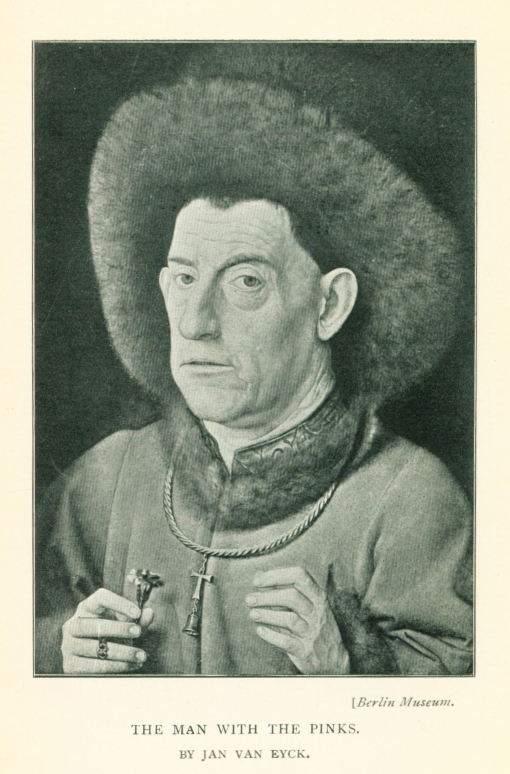

THE MAN WITH THE PINKS

(Berlin Museum)

By Jan van Eyck.

ST. BARBARA

(Antwerp Museum)

By Jan van Eyck.

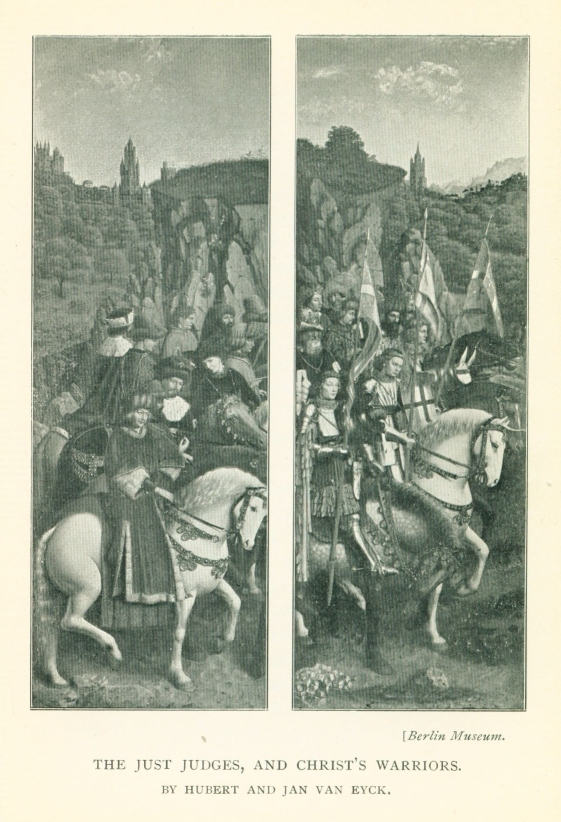

THE JUST JUDGES, AND CHRIST'S WARRIORS

(Berlin Museum)

By Hubert and Jan van Eyck.

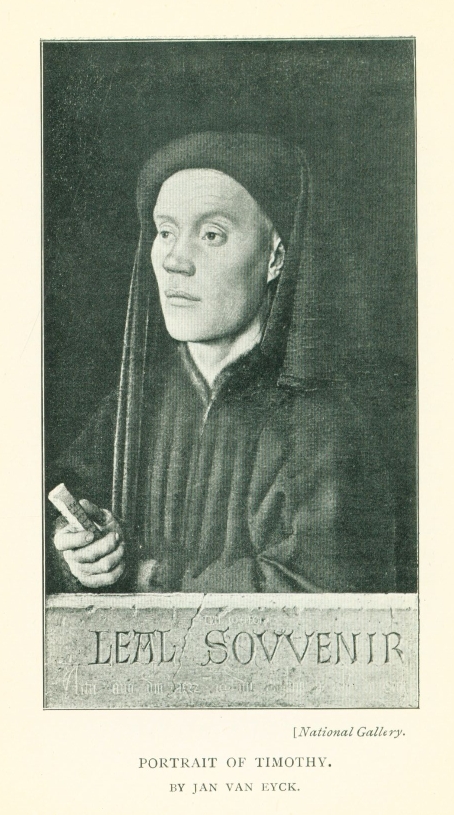

PORTRAIT OF TIMOTHY

(National Gallery)

By Jan van Eyck.

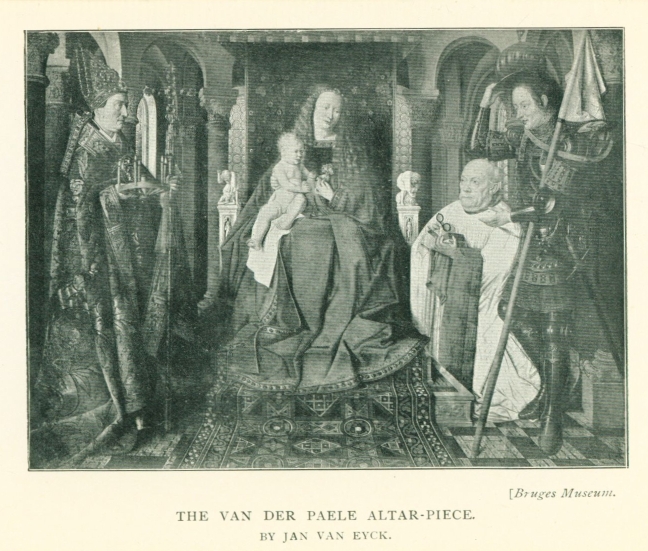

THE VAN DER PAELE ALTAR-PIECE

(Bruges Museum)

By Jan van Eyck.

The unusual activity which during the latter half of the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth centuries throbbed throughout the whole of the Netherlands forms one of the most interesting and surprising studies of national progress that history has furnished.

Geographically and politically, in her arts and in her industries, the country was affected by changes both radical and lasting. Some years before the period which embraces the life of the subjects of this biographical sketch, the German Ocean had invaded the northern territory of the Netherlands, and had disorganised a Parliament and divided a people. At the beginning of the thirteenth century over the whole of that low-lying and marshy tract between Kampen on the east and Amsterdam to westward, and southward to within sight of Nieukerk, the North Sea swept in upon the {2} inland lake of Flevo, swallowing thousands of hamlets, villages, and towns suddenly and completely. Until this time there had been but one Friesland, including Holland, divided only by the Vlie, a small stream hardly to be counted a river. Now East Friesland and West Friesland were divided by this vast stretch of water, the stormy and dangerous Zuyderzee, and it became impossible for Holland to send her representatives to the general assemblies at Aurich. West Friesland was absorbed by Holland, and East Friesland became a self-governing State, and remained such until the power of Charles V. was established. Thus politically as well as geographically was the country disrupted by the forces of Nature.

To trace the rise of the Netherlands as a European Power from a more remote period than the beginning of the fourteenth century would be beyond the range of this sketch; but for the purpose of showing the general advance of the country's interests a brief summary of the events culminating in the wellnigh despotic power of the House of Burgundy may refresh the reader's mind, as they affect the constitution of the nation, and may serve to point cause {3} and effect in the increasing prosperity of the country and in the resulting advance of art; for just as the political influence of the Burgundian Princes spread from their hereditary provinces first over Flanders and Brabant—over that part of the Netherlands which is now known as Belgium—and finally over the Dutch provinces, so the current of art swept from Burgundy to Flanders and thence to Holland.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century Holland was ruled by the House of Avennes, Counts of Hainault. Holland having previous to the accession of the Avennes annexed Zeeland, the three provinces may almost be regarded as the nucleus of the Dutch power. William IV., last of the Hainault line, died childless in 1355. His death was the signal for the outbreak of a long and spasmodic series of civil disturbances between the nobles and the cities and municipalities. These parties, known by the titles of the Hooks and the Kabblejaus (codfish), continued their intermittent strife throughout the succeeding 150 years. In the meantime William IV. was succeeded by William of Bavaria. Then followed his brother Albert, who was in turn succeeded by his son William VI. At the death of the latter {4} the reins of government were left in the uncertain hands of his young daughter, Jacqueline, a girl of seventeen. Jacqueline, it appears, led anything but a happy life. Her cousin, Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, for thirteen years plundered and robbed her, and at her death in 1437 he had already dispossessed her of her lands and reduced her from the position of Sovereign to that of Lady Forester in her own provinces, whilst for himself he had laid the foundation of that Greater Netherlands which by conquest and annexation he proceeded to extend.

Having acquired the principal Netherlands and inherited the two Burgundies and the counties of Flanders and Artois, he had purchased the county of Namur, usurped the duchy of Brabant, and annexed the barony of Mechlin. A few years later he acquired also the duchy of Luxembourg.

Philip was now the ruler of what may be termed a kingdom of several peoples, who, though in a measure distinct, were of similar temperament and character, and who may be counted now as one. Never has conqueror been in a happier position when faced with the problem of welding together his conquests. {5} For Philip ruled those whose interests were similar, and whose characteristics were almost identical—a people born of the sea, strong and fearless, who had lived by strife with their fellows and by strife with Nature; a people born to toil and to hardship, whose battle for life had been with Nature herself—a race which for centuries had fought with swamp and water year in, year out, conquering a mile of morass or patch of barren furze, striving for the soil to live upon, working not for gold, but for life. This nation had now become a power of natural strength and of dominating physique, virile and live and expansive, whose sons, with brooms at their mastheads, should later sweep the seas from whose destructive embrace she had succeeded in wresting herself.

Under the rule of the Burgundian the prosperity of the Netherlands rapidly increased. In Holland and in Flanders, in Brabant and in the other leading provinces, industry and wealth, agriculture, commerce, and manufactures, were ever augmenting. While Philip, in the zenith of his power, flushed with the passion and success of territorial acquisition, busied himself with the glorification of his sovereignty by founding at Bruges, amid a {6} scene of indescribable splendour, the Order of the Golden Fleece, "to the honour of God, of the Blessed Virgin, and of the holy Andrew," a principle more potent than even territorial power was evolving. For in Haarlem an undistinguished sexton wrestled with the intricacies of the printing-press. Lorenz Coster was printing his book of the Dutch language. The question as to the time and place of the invention of printing will probably never be settled to the satisfaction of Holland and Germany; but the men of Haarlem still claim upon very sound and substantial evidence that between 1423 and 1440 their citizen was the first to employ movable type, which is generally considered the invention of printing proper, as distinguished from the more ancient block-printing.

Whatever objection may be legitimately raised to the application of the title "The Good" to a ruler of Philip's character, this Burgundian had many of the qualities that go to the making of a successful monarch. His military talents were considerable; his political methods, though despotic, were practicable. Though he taxed the wealth of his country, he protected and encouraged the commerce and {7} manufactures of Holland and Flanders, their arts and crafts, science and literature. He founded at Bruges the famous Burgundian Library. He remodelled, and to some extent endowed, the University of Louvain. His munificence and princely generosity attracted to his Court at Bruges men of letters like Oliver de la Marche and Philippe de Commines, and famous painters like Jan van Eyck, and perhaps, though we lack documentary evidence, his elder brother Hubert, who gave, perhaps, more to the art of painting than even did Coster to the art of printing, or Philip himself to the sciences of statesmanship and war.

The most salient points in the life and work of these two brothers, who close the period of stiff Gothic medievalism and stand on the threshold of modern art, and whose improvements in the technical methods of their art opened up to their successors unthought-of possibilities, are shrouded in deep mystery, and the most recent research to which a number of thoroughly competent scientific experts have devoted themselves, whilst producing many ingenious theories and deductions, has, in a certain sense, added to the confusion by throwing doubt upon the authenticity of documents {8} and inscriptions which had formerly passed undisputed, and formed the basis of the unstable edifice that had been erected around the vague fame of the brothers Van Eyck. This uncertainty begins with the parentage and the place and date of birth of the two masters, and extends to the two supreme achievements to which they owe their fame—the reputed invention of oil-painting, which was variously ascribed to Hubert and Jan, then denied to both of them, and, finally, given back to Hubert in the form of an improvement on the methods of oil-painting practised during the period; and the much-quoted inscription on the famous Ghent altar-piece, The Adoration of the Lamb, which has been, and must remain, the starting-point for all research in this matter, even though the late Henri Bouchot, Keeper of the Print Cabinet of the Bibliothèque Nationale, suggests that this inscription may have been added when the picture was restored in the middle of the sixteenth century. At every turn we are faced by similar doubts and contradictions, especially in the case of Hubert, about whose life and doings we have so little documentary evidence that we have to fall back entirely upon conjecture and deduction.

THE ADORATION OF THE LAMB.

BY HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK.

If Joes van Eyck and Margaret van den Huntfanghe, who are entered in the register of the Ghent Guild of Painters for 1391, are the parents of the two masters who have made the name of Van Eyck immortal, we should have proof of their descent from artistic stock, which may be taken for granted in view of the fact that not only Hubert and Jan, but also a third brother, Lambert, and a sister, Margaret, devoted themselves to the art of painting, though Lambert—if he really be responsible for the pictures which stand to his credit—was a man of but mediocre talent; whilst we have no evidence of the activity of Margaret, who was most probably a miniaturist or illuminator.

It is believed that Hubert (or Huybrecht) van Eyck was born at Maaseyck, or perhaps at the village of Eyck near that town, between 1366 and 1370, and that he received his artistic training either at Cologne or at Maastricht; but the first definite mention we have of him {10} is in Ghent, where he eventually settled, and where, in 1424, the archives record that he was paid certain sums for drawings. Though Mr. Weale and other authorities hold the view that, before settling in Ghent, Hubert must have travelled to the South of Europe, there is absolutely no evidence to this effect. The paintings of the two brothers certainly contain details which reveal intimate acquaintance with Southern vegetation and mountain formation; but, as will be seen later, Mr. Alfred Marks has fairly well established the fact that the younger brother, Jan, must be held responsible for such paintings or portions of paintings as prove the knowledge of Nature in the South of Europe.

The name of Hubert van Eyck occurs in two other documents, quoted by Edmond de Busscher in his "Recherches sur les Peintres Gantois," but the authenticity of both these entries has lately been questioned. The first of them, which is proved to be a forgery, records the admission of Hubert and of his sister, Margaret, into the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Rays at Ghent in 1419; the other the affiliation of Hubert and Jan, in 1421, to the Corporation of Painters and Sculptors of Ghent. {11} According to the wording of the latter entry, it may be gathered that the election of the two masters was so enthusiastic and unanimous that the Corporation dispensed with the conditions and formalities usual on the admission of free masters to the guild. This unusual affiliation, of which the Livre du Métier Gantois does not reveal another example, is there quoted as a homage rendered to the memory of Michelle de France, Countess of Flanders, and first wife of Philip the Good, who appears to have held the two brothers in special favour. The Corporation, in thus granting to them the professional franchise of Ghent, at the same time expressed their esteem for their talent, and the pious remembrance in which they held the memory of their Queen Consort.

Of Hubert's early work we have absolutely no record, and no picture is known which bears his signature. Indeed, the only paintings which can with absolute certainty be assigned to him are the great Ghent altar-piece, painted for Jodoc Vydt, on which he was engaged at the time of his death, and which was finished six years later by his brother Jan; and the shutter of a triptych at the Royal Gallery at {12} Copenhagen, which represents Robert Poortier, of Ghent, protected by St. Anthony, with the Angel Gabriel on the reverse. Robert Poortier's will, made in 1426, a few months before Hubert's death, mentions this triptych as being in the master's workshop. On the internal evidence of these two authentic works attempts have been made to trace Hubert's hand in several other pictures, though their number is so far restricted to only seven. It has been suggested that Hubert may in the earlier years of his career have devoted himself to miniature painting; and the wonderful Turin miniatures published by M. Paul Durrieu in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts (January and February, 1903), which date from the same period, show such marked kinship with Hubert's conception and style that they may well be the work of his own hand. The scarcity of his paintings would thus be accounted for if, anterior to the experiments which led to the invention of the new method of oil-painting about 1410, Hubert had exercised his rare gifts in a different field.

From the wording of his epitaph, which has been handed down to us, it is made clear that Hubert died on September 18, 1426. As translated by Sir Charles Eastlake, in his "Materials {13} for a History of Oil-Painting," this epitaph runs as follows: "Take warning from me, ye who walk over me. I was as you are, but am now buried dead beneath you. Thus it appears that neither art nor medicine availed me. Art, honour, wisdom, power, affluence, are not spared when death comes. I was called Hubert van Eyck; I am now food for worms. Formerly known and highly honoured in painting, this was all shortly after turned to nothing. It was in the year of the Lord one thousand four hundred and twenty-six, on the eighteenth day of September, that I rendered up my soul to God, in sufferings. Pray God for me, ye who love art, that I may attain to His sight. Flee sin, turn to the best, for you must follow me at last." Hubert was buried in the crypt of the Cathedral of St. Bavo at Ghent. When, owing to some structural alterations to the church, this crypt was destroyed, the tombs, including Hubert's, were removed and the bones dispersed. Only Hubert's right arm was placed in an iron case and exhibited as a relic.

The date of Jan van Eyck's birth is as uncertain as that of his brother's. Tradition has it that the two brothers are portrayed on the panel of the great Ghent altar-piece, which represents The Just Judges. These portraits suggest a difference of about twenty years between the two, so that the birth of Jan would have to be placed somewhere between 1386 and 1390. Hubert being thus about twenty years his senior, it is natural to suppose that Jan received from him his early education in matters of art. Guicciardini, van Mander, and other early writers, affirm that the two brothers worked in collaboration, and there is no reason to doubt that Jan in his early years assisted his brother in many or most of his paintings—perhaps even in the Ghent altar-piece, which he finished after the elder brother's death. It is certainly a curious fact that, with a single exception—the completely over-painted Enthronement of St. Thomas of Canterbury at {15} Chatsworth—all the signed pictures by Jan bear dates posterior to the death of Hubert. And it is equally significant that the first of this series of ten signed pictures is dated 1432, the year of the completion of the Ghent altar-piece, which was the last work in which both brothers had a share.

THE ENTHRONEMENT OF THOMAS À BECKET,

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

The chief events in the life of Jan van Eyck can be gathered fairly accurately from contemporary records and documents. In 1422 Jan entered the service of John of Bavaria, at that time Duke of Luxembourg, whose household accounts show the payment of a weekly wage to the artist, from October 25, 1422, till September, 1424, for the decoration of the palace at the Hague. M. Bouchot mentioned an earlier record of Jan's doings, when he believed he discovered him at Cambrai decorating a Paschal candle. But the eminent French critic probably confused Jan van Eyck with one Jan de Yeke, whose name occurs in the accounts of the Cathedral of Cambrai as that of a man employed in 1422 and many following years in painting crosses, clocks, and candles on the outer wall of the cathedral to deter the passers-by from committing nuisances!

In the spring of 1425 Jan van Eyck was {16} appointed varlet de chambre to Philip the Good, and though this princely patron availed himself of the master's services as a painter, it would appear from a letter signed by Philip, and bearing the date March 12, 1434, that the appointment of Jan to the position of Court painter to the Burgundian Prince only took place in that year (1434). Still, as varlet de chambre Jan van Eyck must have enjoyed a position of considerable trust and emolument at the hands of his august master, for on more than one occasion we find him entrusted with important missions, some of which took him to the Portuguese Court. The first of these excursions took place when he had resided for three months at Bruges. On his return he went at Philip's order to live at Lille, where he remained until 1428. His missions were generally of a secret nature, but on one of these occasions, in the year 1428, we find Jan again absent in Portugal, returning to the Court of Philip in the suite of Isabella of Portugal, who was destined to become the royal consort. Gachard, in the Collection de Documents Inédits concevnant l'Histoire de Belgique, gives a detailed account of the artist's movements from his departure from Écluse on October 19, 1428, to his {17} return in January, 1430. According to these dates, which are gathered from contemporary documents, the ambassadors with the Infanta set out from Lisbon on October 8, 1429. The apparent discrepancy between these dates and that of January 10, 1429, which, at the Golden Fleece Exhibition at Bruges in 1907, was given as the date of the foundation of this Order, and consequently of the nuptials of Philip and Isabella and of Jan's return to Bruges, is easily accounted for if we remember that the beginning of the year was then reckoned from March 1, so that January, 1430, of our own reckoning would tally with January, 1429, of the contemporary calendar.

Jan's first duty on arrival at the Portuguese Court was to paint the portrait of the Princess. It appears that he was at work upon this picture for a month. Several portraits of Isabella are still extant painted in the manner of the van Eycks, and pointing to the same origin, but none has so far been discovered to possess qualities or details which would justify its identification as Jan's original panel. Evidently Jan's portrait was pleasing to the eye of the Lowland monarch, for upon Philip expressing his satisfaction with the personal appearance {18} of Isabella, the ambassadors and the bride immediately embarked on the homeward journey. Soon after his return—namely, in 1431—Jan bought a house in Bruges, where he married and continued to work, after the completion of the Ghent altar-piece in the following year, until his death, which took place about the end of June, 1441. He was buried in the churchyard of St. Donatian at Bruges, but his body was subsequently removed to a vault near the font of that church.

Mr. Weale, while arranging the archives of St. Donatian at Bruges, discovered in the account of the fabric of the church for the year beginning June 25, 1440, and ending June 24, 1441, entries of sums received for the grave of Jan van Eyck and for the ringing of the funeral bell, and in the obituary of the church his anniversary set down as celebrated on July 9. In an article in the Burlington Magazine (1904) Mr. Weale makes the following comment: "Hence it appears certain that he died on July 9, 1440. This date, now generally accepted, is, however, incorrect. Two entries in the account of Walter Poulain, Receiver-General of Flanders for the year ending December 31, 1441, prove that John's death {19} took place in 1441, but leave the exact day uncertain." Three entries show that Jan died about the end of June, and that on July 22 a grant of 360 livres—the equivalent of her husband's salary for half a year—was made to Jan's widow by the Duke Philip in recognition of the services rendered by her deceased husband. It also shows that Jan's wife was named Margaret, and that he left at least two children—one, the Duke's godchild, Philip or Philippina, born in June, 1434; the other, Lyennie, who became a nun at Maaseyck in 1449, which lends colour to the theory that Maaseyck was her father's birthplace.

His epitaph, as translated by Sir Charles Eastlake, runs: "Here lies Joannes, who was celebrated for his surpassing skill, and whose felicity in painting excited wonder. He painted breathing forms, and the earth's surface, covered with flowery vegetation, completing each work to the life. Hence Phidias and Apelles must give place to him, and Polycletus be considered his inferior in art. Call, therefore, the Fates most cruel, who have snatched from us such a man. Yet cease to weep, for destiny is immutable; pray only now to God that he may live in heaven."

Tradition has for centuries connected the name of Van Eyck with the invention of oil-painting, and has fixed upon the year 1410 as the date of this invention. This, at least, is the year given by such early writers as Guicciardini, Vasari, Opmeer, and Karel van Mander. Vasari, indeed, gives a most detailed and circumstantial account of this epoch-making event, which, according to the Aretine biographer, was brought about by the single-handed efforts of Jan. And it is easy to understand that the fame of the elder brother had in the sixteenth century become obscured and merged in that of the brilliantly successful Jan, the varlet de chambre and official Court painter. This "Giovanni of Bruggia," Vasari tells us, "after having given extreme labour to the completion of a certain picture, and with great diligence brought it to a successful issue, he gave it the varnish and set it to dry in the sun, as is the custom. But whether because {21} the heat was too violent, or that the wood was badly joined or insufficiently seasoned, the picture gave way at the joinings, opening in a very deplorable manner. Thereupon Giovanni, perceiving the mischief done to his work by the heat of the sun, determined to proceed in such a manner that the same thing should never again injure his work in like manner. And as he was no less embarrassed by his varnishes than by the process of tempera-painting, he turned his thoughts to the discovery of some sort of varnish that would dry in the shadow, to the end that he need not expose his pictures to the sun. Accordingly, after having made many experiments on substances, pure and mixed, he finally discovered that linseed oil and oil of nuts dried more readily than any others of all that he had tried. Having boiled these oils, therefore, with other mixtures, he thus obtained the varnish which he—or, rather, all the painters of the world—had so long desired. He made experiments with many other substances, but finally decided that mixing the colours with these oils gave a degree of firmness to the work which not only secured it against all injury from water when once dried, but also imparted so {22} much life to the colours that they exhibited a sufficient lustre in themselves without the aid of varnish; and what appeared to him more extraordinary than all besides was that the colours thus treated were much more easily united and blent than when in tempera."

Vasari then proceeds to tell us of Jan's great success, of the "blameless envy" of all other artists in Flanders and abroad, from whom he would jealously guard his secret, until, in his old age, he imparted it to "his disciple Ruggieri da Bruggia," a name which surely can hide no other personality than Rogier van der Weyden's. Of Hubert never a mention, save a short reference in the last volume, in the chapter on "Divers Flemish Artists." As in most of Vasari's anecdotes, there is probably a foundation of truth to the elaborate network of fiction. The incident explained by him at great length may have occurred, but its hero can only have been Hubert, and not Jan, who was then a mere youth working in his brother's bottega, and may have assisted Hubert in his experiments. Though it has since been doubted that Hubert or Jan van Eyck actually invented oil-painting, no evidence has yet been discovered to prove they were not the first to employ oil {23} as a medium in putting colour on the prepared panel. It is true that oil as a protective varnish was frequently used during the fourteenth century, and it is probable that some kind of oil-colour was employed in the colouring of statuary and in the painting of banners at an early period. For this reason the statement that Hubert and Jan van Eyck "discovered painting in oils" has been disputed, and generally accepted as inaccurate, but the question is one rather of terminology than of the technical point.

As the term "oil-painting" is generally accepted to-day, it is fairer to credit these brothers with the invention, than to speak of their achievement as an improvement in oil-painting, for hitherto the medium in common use had been a preparation of gum and white of eggs. And as there is neither definite proof nor any good evidence that oil had ever been used as a medium to mix the colours for panel-painting before Hubert and Jan made their experiments, we surely have an easy distinction to draw. The brothers Van Eyck were the first successfully to mix the oil with the colours for painting, and this process is what we now understand as "painting in oils." The use of {24} oils as a protective or varnish does not enter into the painting, since such had only been used on the completion of the work.

For the rest, the brothers either acted more generously than Vasari would have it, or they did not altogether succeed in guarding their precious secret, for their method appears to have been fairly generally practised at Ghent about 1420. We find, for instance, that in 1419 the "free painters," Willem van Appoele and Johannes Maertens, received a commission to paint some pictures for the town hall of Ghent in "good oil-colours." It is also certain that Rogier van der Weyden—Vasari's Ruggieri da Bruggia—never was a pupil of either Jan or Hubert van Eyck.

The position occupied by Hubert and Jan van Eyck in the history of art is one of unparalleled importance. A deep gulf divides them from all their immediate precursors, who seem to belong altogether to a different epoch—nay, a different world. Just as their improvement in the technical methods of their craft opened up a vista of till then unthought of possibilities, so their conception of life and of pictorial form marks the beginning of a new era, the passing of the vague mediæval idealism into an art that is based upon the close study and loving appreciation of Nature. Perhaps too much stress has been laid upon the so-called "realism" of the brothers van Eyck, and more especially of Jan. Again and again critics have insisted upon Jan's uncompromising love of literal truth, upon his insistence on details that are in themselves at times repulsively ugly. This realism was tempered with deep sentiment and a sense {26} of style which kept such details well subordinated to the general scheme, and it is in this respect that Jan van Eyck stands immeasurably above Melchior Broederlam, who occupied the position of varlet de chambre and Court painter to Philip the Bold, the grandfather of Jan's patron. Broederlam, indeed, as may be seen in his famous altar-piece at Dijon, seems to be a far more pronounced realist than Jan van Eyck, simply because he lacks that sense of style and harmony and subordination—in short, that concentration—which makes us forget the realistic detail in the beauty of the complete thing.

The real precursors of the van Eycks were the sculptors who carved the tombs, monuments, and reliefs in the churches of Tournai. In these we first find the faithful adherence to the facts of Nature and the understanding of the subtleties of form which in painting appear first in the works of the brothers van Eyck, who may have also owed much of their knowledge to the flourishing school of Flemish miniature-painters, if, indeed, Hubert in his early days did not actually practise this art. Yet, even though the new era in painting is, as it were, heralded by the new tendencies in plastic art—just as in {27} Italy Giotto was preceded by the sculptor Niccolo Pisani—there is something wonderful, something almost difficult to realise, in the sudden appearance of complete and perfect works of art, like the paintings of the van Eycks, that with masterly sureness express the whole essence of the Gothic style, whilst at the same time they reveal a new understanding of the inexhaustible beauty of Nature, a keen perception of structural growth and of individual characteristics, and, above all, an almost modern understanding of the play of light upon figures and objects in and out of doors.

The picturesque, brilliant, varied life of such cities as Bruges and Ghent at the beginning of the fifteenth century cannot have failed to stimulate the artists' power of observation, to sharpen their perception of the differences of race, gesture, and costume; for the streets and squares of the rich commercial centres of Flanders were filled from morning to night with ever-moving crowds of courtiers and merchants from all parts of the world—Spaniards and Italians, Germans, and Slavonians, and even Moors and Turks, all in their different costumes and following their different customs. At the same time the painters' eyes were {28} constantly met by the wonders of the creations of architects, armourers, and other craftsmen who flourished under the protection of the Burgundian rulers; and one may well understand the love and enthusiasm with which a receptive artist like Jan van Eyck applied himself to the faithful delineation of the splendours and of the seething life by which he was surrounded.

Although the two brothers were in the habit of working together upon the same pictures, which has given rise to many disputes as to the authorship of unsigned works, and although Jan, the realist, at times approached, though never equalled, the spirituality and decorative sumptuousness of Hubert, whilst Hubert, the stylist and greater mind of the two, sometimes vied with Jan in the minute and exquisite elaboration of details, the signed works of Jan and those parts of the Ghent altar-piece which are unquestionably Hubert's own have made it possible to characterise the distinguishing qualities of the two masters. Hubert far exceeds his brother in monumental impressiveness, in grandeur of style, in idealistic significance, in sumptuousness, and even in sense of beauty. Even the folds of his draperies have a fulness and a noble swing which form a striking {29} contrast to the more laboured irregularity of Jan's, as may be seen in comparing the garments of God the Father, the Virgin Mary, and St. John, of the Ghent altar-piece, with the curiously broken folds of Barbara's dress in Jan's picture at Antwerp.

THE MAN WITH THE PINKS.

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

The conception of such ideas as are embodied in the Adoration of the Lamb, or in the Triumph of the Church over the Synagogue, at the Madrid Museum, would also have been quite beyond the pale of the more prosaic Jan's imagination. Jan, on the other hand, excelled in stating the reality of the visible world. Generalisations of human types or of landscape features are unknown to him. He was the first to fix upon his panels all the carefully studied and exquisitely wrought details of the actual world—sky and mountain and river, forest and fields, flowers and trees, and the churches and castles, houses and bridges, placed in Nature by human hands. It is scarcely too much to say that he was the first landscape-painter, just as he was the first portrait painter in the modern sense of the word—the first who could paint a scene so that it could be identified after the lapse of centuries, the first who could paint a portrait so that the model {30} stands before us living and breathing, in all his beauty or ugliness. To appreciate the keenness of his vision one has only to examine the marvellous Arnolfini group at the National Gallery, with its almost scientific treatment of softly diffused indoor light. A comparison of this picture, from the point of view of lighting, with anything that was painted before the days of the van Eycks will reveal perhaps the greatest step forward that is on record in the whole history of painting.

When piecing together the lives of the brothers van Eyck, it is necessary to delve into a confusing mass of conflicting statements—evidence which is only in part to be relied upon, and the theories of those who have devoted a vast amount of time and labour to the unearthing, sorting, and arranging of such evidence as they have been able to lay their hands upon. Incomplete as the records are, we must, until further evidence has been discovered, accept the obvious conclusions from the indisputable data left to us.

We have ten unquestionably genuine signed pictures by Jan, and a small group of others which may, from internal evidence, be safely ascribed to the same source. We know that the great Adoration of the Lamb, though designed in its entirety by Hubert, is the combined work of the two masters. We know also that the Copenhagen panel of Robert Poortier {32} was in Hubert's studio at the time of his death—perhaps unfinished. The remaining pictures generally accepted as genuine van Eycks have been variously ascribed to Hubert, or to Jan, or to their united efforts. In view of the fact that not a single really authenticated work by Hubert alone is known, special significance must be attached to a statement, several times repeated by early writers, that Hubert and Jan "continually painted on the same works."

In trying to solve the difficult question which part of the extant oeuvre is Hubert's and which is Jan's, our knowledge of Jan's journeys to the South assumes considerable importance. For Hubert's travels we lack proof—they are mere conjecture. But there is documentary evidence of Jan's journey to Portugal in 1428, in addition to which Mr. Weale has, I understand, recently unearthed some further documents which establish another and earlier journey of Jan to Spain. On these travels Jan must have become well acquainted with certain plants peculiar to the South, and especially the dwarf palm or palmetto, which is confined almost exclusively to Spain and Portugal. It is therefore not unreasonable to assign to him those {33} portions of the disputed pictures in which this palmetto appears. Some authorities hold that Jan did not have any independent artistic career before Hubert's death, and that in the division of labour Hubert's share was, as a rule, the general design and the painting of the figures, whilst Jan filled in the landscape and architectural backgrounds.

The collaboration theory has been advanced by Mr. A. Marks, whose knowledge of Flemish art is profound, and whose deductions are as conscientious as they are convincing. To him we are indebted for an interesting paper upon the subject, which is at once exhaustive and reasonable. To retail all that Mr. Marks advances in support of his theory would be to reprint his treatise in toto; but though it is impossible here to follow all his arguments, it is equally impossible to avoid reference to the valuable correspondence between him and Mr. James Weale in the Athenæum, between November, 1902, and April, 1903. This correspondence arose from an article by Mr. A. Marks in the Athenæum in May, 1900, in which attention is drawn to the presence of the palmetto in the picture of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata (now in possession of {34} Mr. J. G. Johnson, Pennsylvania; a copy in Turin), which picture had been formerly variously ascribed to Henri met de Bles, Joachim Patinier, and Mostaert. Mr. Marks has since supplemented and explained his views in the essay mentioned; whilst Miss Frances Weale has published an excellent study on the "van Eycks," which, in a concise and interesting form, presents her father's views on the subject.

It is, of course, likely that nothing is proved as to the authorship of certain paintings by the presence or absence of the exotic plants or other details ascribed to one or other of the brothers. Supposing the assumed visit of Hubert to Southern Europe to be a fact, Jan may have made use of his brother's studies to embellish his landscapes; or Hubert may have utilized Jan's studies. But either supposition is extremely unlikely. We have certain proof that Jan did several times visit the South, while Hubert's sojourn in these parts is pure surmise; and not only is it likely that, rather than make use of second-hand material, Hubert left portions of the pictures to be painted by Jan, but the examination of the various pictures reveals the same hand in the painting of the {35} recurring details. We must, then, take the facts and the most likely deductions in preference to deductions drawn from data which are merely conjectural.

Documentary evidence proves that Jan, immediately after his reception by the King of Portugal on January 12, 1429, began the work of painting the portrait of the Infanta, which, by the way, was executed in tempera, and not in oil. This painting is, unfortunately, lost, and though there are several portraits of Isabella now extant, of which one at least may be a copy of Jan's picture, there is nothing in any of them that can be traced to this master. He took a month over its completion, and while the Court and Embassy were awaiting the decision of Philip, to whom the picture had been sent, Jan and his colleagues had time to visit several places of interest and people of distinction. They travelled to the north to see the shrine of St. Iago of Compostella; then to the south, where they were received in turn by the Duke of Arjona and the King of Castile; and then to Granada, in the extreme south, where they visited the King of that city. It is stated that they also visited many other places; and, as from Granada they returned to Lisbon, {36} they must have passed through the country lying between Cordova and Seville.

Now, through the whole of the south-eastern portion of the peninsula the palmetto, or dwarf-palm, flourishes abundantly, and Jan could not fail during his tour to become well acquainted with it. In a letter which Mr. Marks quotes in his paper read at the Royal Society of Literature, June 24, 1903, Mr. Luffmann, Director of the School of Horticulture in Melbourne, says that the triangle formed by Seville, Cordova, and Osuna, is "a piece of country which is literally overrun by the plant," and that the root of the palmetto is commonly used in those parts as fuel. In Italy it is but of rare occurrence, though it grows in some of the islands of the Mediterranean; whilst in the parts of Spain and Portugal visited by Jan it is almost impossible for the visitor to avoid seeing it.

Failing, then, even the probability that Hubert ever saw the palmetto growing, we must credit Jan with the painting of this plant, which, like all the other exotics, must have been carefully studied from nature, for they are represented in most minute, careful, and conscientious manner, and are absolutely true to {37} life. The palmetto occurs in the picture of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata (above referred to); in the St. Anthony with the Donor at Copenhagen; and in The Three Marys at the Sepulchre in the collection of Sir Frederick Cook at Richmond. The portions of these paintings by Hubert van Eyck, where the palmetto occurs, may therefore be safely ascribed to the hand of Jan.

Other exotic plants, which are not restricted to Spain and Portugal, occur in these pictures; but they are painted by the same hand, and betray the same loving adherence to truth, and a similar familiarity with the plants as they grow. It is therefore patent that they, too, must be ascribed to Jan, for it is impossible to suppose that the younger brother's work on these pictures was simply that of adding the by no means necessary dwarf-palm to Hubert's completed landscapes. Jan was probably responsible for the design and execution of these landscapes. These other exotics also occur in the Ghent altar-piece, in the Calvary of the Berlin Museum, and in the copy, at the same museum, of a lost Virgin and Child, Mr. Marks produces further evidence to prove that Jan must have painted not only the foliage, but the {38} whole of the landscapes where the little palm appears, including in most cases the architecture. He draws attention to the architectural features in the Chancellor Rolin with Saints in the Louvre, and the signed and dated altar-piece by Jan in the museum at Bruges: "The architecture in these pictures is not a real architecture—that is, it has not been copied from any actual examples.... Agreement is general that it is an architecture invented, not merely copied." These pictures furnish evidence of the painter having visited Italy, for marble is represented in a most lavish manner. This marble is not characteristic of Northern architecture; its use is distinctly Italian. The painting of it displays the usual care and conscientiousness common to all Jan's works. Further points cited by Mr. Marks as evidence of Jan's work in various pictures are the representations of snow-mountains in various works, and the presence of a flying flock of geese.

The former is of greater importance, as this again points to acquaintance with the South, where alone the painter could have seen snow-mountains. Now, as very similar architecture to that in the altar-piece at Bruges, which is signed by Jan van Eyck, is found in the Chancellor {39} Rolin (Louvre), the Virgin and Child (Dresden), and the Carthusian Monk with Saints (Gustave de Rothschild, Paris), the suggestion is clear that in all these pictures the architecture is the work of Jan, and several notable critics hold this view. In three of these four paintings we find the snow-mountains—namely, in the Dresden triptych, the Chancellor Rolin, and the Carthusian Monk. And having established Jan as the author of these snow-mountains, we must credit him with the landscapes where this feature occurs in other pictures—i.e., the Ghent altar-piece, the Crucifixion of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the Calvary of the Berlin Museum, and the Three Marys of Sir Frederick Cook. The theory that Jan is responsible for the snow-mountains is amply supported by the very reasonable deduction that he must at some time have visited Italy. This is gathered from the Italian character of the architecture, together with the snow seen in the Rothschild picture, the Chancellor Rolin, the Carthusian Monk, and the Dresden picture. The theory is further supported by the presence of the palmetto together with snow-mountains in the Three Marys of Sir Frederick Cook. Here the palmetto proves the authorship of the {40} landscape, and as the view contains snow-mountains it very materially strengthens the supposition that it was Jan, and not Hubert, who painted them, and who consequently must have been to the South of Europe—probably Italy—to have seen them.

The flock of geese, which appears in no fewer than six pictures in addition to Jan's signed St. Barbara at Antwerp, is of very much less importance than the snow-mountains and the palmetto, for here the only use that can be made of it as evidence is its frequent repetition. It is found in the landscapes of the Ghent altar-piece, in the Chancellor Rolin, the Carthusian Monk, another version of the same subject in the Berlin Museum, St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, and in the Three Marys. But the flock of wild-geese is not a feature made use of by the van Eyck brothers only. It seems to have been of common occurrence in several other Flemish painters both before and after the days of the van Eycks. Nevertheless, its presence in the pictures enumerated has been brought forward as supplementary evidence to prove the collaboration of Hubert and Jan.

So far, then, evidence has been shown to prove Jan's share in the following pictures: the {41} Chancellor Rolin, the Virgin and Child (at Dresden), the Carthusian Monk in the Rothschild Collection, St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, St. Anthony and the Donor (at Copenhagen), The Three Marys at the Sepulchre, the Crucifixion (at St. Petersburg), the Calvary (at Berlin), and the great altar-piece at St. Bavo, Ghent. Still another point which has been generally urged to prove collaboration of the two brothers is the appearance of their portraits in certain pictures. They are seen in the panel of the Ghent altar-piece representing the Just Judges, in the copy of the lost Fountain of Life or The Triumph of the Church over the Synagogue in the Madrid Museum, and also, it is said, in the Crucifixion of St. Petersburg.

Though the theory of collaboration is an old one, doubts have arisen amongst modern critics, who have shown a growing tendency to ascribe the majority of the unsigned works solely to the elder brother, which attribution is refuted not only by the arguments here set forth, but by many early writers, including Guicciardini and van Mander, both notable and reliable historians.

Before leaving the question of collaboration, a few words must be said concerning the {42} controversy that has arisen over the Ghent altar-piece. This painting is indisputably the masterpiece of the van Eycks, and is of stupendous proportions. The panel of the Adoration of the Lamb, from which the whole alter-piece takes its name, and the shutters depicting the Just Judges, the Warriors of Christ, the Holy Hermits, and the Holy Pilgrims, have by many critics been attributed to Hubert's unaided efforts. It is therefore interesting to examine the landscape backgrounds of these five panels, and to consider them in the light of the evidence deduced from the backgrounds of the other "collaboration" pictures. Evidence is needed to prove that Jan's work was not merely confined to finishing the picture after his brother's death (the inscription states that it was begun by Hubert and finished by Jan), which in itself, of course, does not prove collaboration of the brothers.

In the first place, Jan's handiwork must be identified. In the pictures already discussed it has been proved fairly conclusively that Jan is responsible for the painting of the exotic plants, the snow-mountains, the flock of wild geese, and the architectural setting. The landscapes in the Ghent altar-piece contain exotic {43} plants, wild geese, and snow-mountains. Of the latter it is difficult to speak; they are whitish in colour, but their formation is neither so natural nor so well designed as in the Three Marys. The exotic plants alone prove Jan's work here. The birds may, or may not, be very important. They serve, however, by their repeated appearance in Jan's other pictures, as auxiliary evidence. The question for proof, however, is not the presence of Jan's work on this picture, but the presence of his work before the death of his brother. And from this point of view it is significant that, though other exotics are present in profusion, the palmetto—a sure result of Jan's visit to Portugal—does not appear. The whole work is stated in the inscription to have been finished on May 6, 1432, two years after Jan's return from Portugal. Now, the absence of the palmetto from this picture points to one of two conclusions—either the work left for Jan to do in the completion was comparatively trifling, or that the greater part of the picture, including the design of the landscapes, was already finished before Jan met with the palmetto.

That the work of the younger brother was not insignificant is distinctly stated in the text {44} of the inscription: "The painter, Hubert van Eyck, greater than whom none is to be found, began [the work]; the bulk was completed by his brother Jan, second to him in art, relying on the request of Jodoc Vydt. This verse invites you to contemplate that which was completed on May 6, 1432." This translation from the Latin is chosen from three versions. The other renderings seem to be given by those who would translate the word pondus as work, and thus give the younger brother credit for no more than finishing an incomplete picture. The text has, however, been translated by several learned scholars, who are entirely free from the taint of partisanship, and it is now generally agreed that the translation given here is the correct one.

There is yet another possibility which the absence of the palmetto points to—namely, that the picture was practically finished before Jan's visit to Portugal, save some very minor details, which were completed in 1432, The presence of the other exotics points to this view being correct, for it would obviously be unlikely that Jan should omit the palmetto from all these five landscapes after his careful studies of his favourite plant. The other exotics, not being {45} a result of the journey, may very well have been painted before 1429. Collaboration in this work is further proved by the portraits of the two brothers.

The supreme masterpiece of the brothers van Eyck, the work which, in the history of Flemish art, has played the part that was allotted to Masaccio's frescoes at the Carmine, Florence, in the art of Italy, is the gigantic polyptych painted for the chapel of the Vydt family in the Cathedral of St. John (now St. Bavo) in Ghent, and known from the subject of the chief panel as the Adoration of the Lamb. In its original form this altar-piece, which is now divided between St. Bavo Cathedral and the museums of Berlin and Brussels, was composed of twelve interior panels and a predella (which has unfortunately been destroyed). Including the backs of the shutters, which, like the panels themselves, are covered with the most minute and exquisite painting, the painted surface extends to over 1,000 square feet. The centre panel alone, from which the whole altar-piece takes its name, measures 7¼ feet in width by 4½ feet in height.

Horizontally the whole altar-piece is divided into three portions. The central panel of the middle tier is occupied by the Adoration of the Lamb. Like the rest of the picture, it is treated in a decorative spirit, the grouping of the figures, the architecture, and the foliage being almost geometrically arranged and balanced. In a very beautiful and peaceful landscape is set up, on a green mound in the centre, an altar, upon which stands the Lamb of God. Its breast is pierced in the customary manner, the sacred blood flowing into a chalice at its feet. Immediately around the altar fourteen angels, symbolical, probably, of the stations of the Passion of Christ, kneel in adoration. The two in front of the altar offer incense, while emblems of the Passion are held by others. The cross is held on the left, and the pillar of the scourging stands on the right. In the foreground, also in the centre and below the altar, is the Fountain of Life, which divides two groups of worshippers: on the left are the Jewish prophets and patriarchs of the Old Testament, whilst the crowd on the right is composed of Popes, Bishops, priests, monks, and laymen. In the background, emerging from the luxuriant forest immediately behind {48} the altar, two processions slowly wend their way. The group on the right is composed of holy women, foremost of whom come St. Agnes with a lamb, St. Catherine, and others. The Procession on the left again includes Popes, Bishops, and monks. These are said to be the confessors. Above all hovers the Holy Ghost in the form of the dove.

The painting of these figures is most exquisite. The draperies are soft and pleasing; the colour is deep and rich; while the faces are remarkable for their character and variety of expression. The jewels and ornaments worn by some of the Popes and Bishops are drawn with loving care, and the enrichments of the vestments betray a patience and skill that create wonder. In the distance, above the trees, are seen cities with many towers and churches, behind which are hills in the remote distance. The foreground of the beautiful, soft, spring-like grass is profusely enriched by the growth of innumerable flowers and shrubs, all of which are painted with consummate skill and truth. The whole picture makes a profound effect by its sumptuous splendour, and by the masterly disposal of light and shade.

The two panels on the left are the Just Judges {49} and Christ's Warriors. In the Judges the whole lower half of the picture is taken up by figures on horses. Behind a cliff in the middle distance is seen a forest and some buildings of elaborate architecture, which may represent tribunals. The bridles and trappings of the horses are richly jewelled, and altogether the best is made of the opportunity of rendering with goldsmith-like precision all manner of gorgeous materials, costly and beautifully emblazoned banners, and armour and trappings of beautiful design. Tradition has it that two of the Judges are portraits of the painters, the one in a black garment with a red rosary, who is turning towards the spectator, being the younger brother Jan. To strengthen the theory that this figure was painted by Jan after Hubert's death, Mr. Weale suggests that the black habit and red rosary denote mourning, probably for his brother Hubert.

As regards the other panel, Mr. Six has advanced an interesting theory with respect to the soldier who wears a blue head-dress. He calls attention to a pentimento in substituting for a crown on this figure the blue head-dress. Mr. Six claims to have identified this figure as Jean Sans Peur, who probably saw the painting, {50} and objected to being represented with a crown while Godfrey de Bouillon wore only a fur cap, and therefore persuaded the painter to alter it to the blue cap or bonnet which was the badge of the Burgundians against the Armagnacs. From this the supposed alteration must have taken place a little after 1410, whereas, according to early art historians, the altar-piece was only begun between 1415 and 1420.

THE JUST JUDGES, AND CHRIST'S WARRIORS.

BY HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK.

Though the limitations of the present little volume make it impossible to reproduce the other panels which originally formed part of the colossal altar-piece, it will not be out of place here to describe them in detail, as they all form part of a wonderfully complete and harmonious scheme. As pendants to the Judges and Warriors, to the right of the central panel were the Holy Hermits and the Holy Pilgrims. Rocks, cliff, and foliage are found in the background of the hermits, but, as suggestive of retirement and remoteness, no architecture is seen. The pilgrims are represented walking up a valley towards the spectator. On the right, in the background, is a hill covered with various trees, and in the distance is seen a river and meadows, with a town and low hills beyond. The pilgrims are led by St. Christopher, {51} whose giant proportions tower above the rest of the procession.

The upper tier of the polyptych consists of seven panels, or rather three panels, the combined width of which corresponds with that of the Adoration panel below, and two shutters on each side. The grand figure in the centre panel, majestically enthroned, has been variously held to represent God the Father and Christ, and the Latin inscription may be equally applied to both. Perhaps it was the painter's idea to personify both in one figure. On His brow is the Crown of Heaven, and at His feet the Crown of Purity and Innocence, which the Lamb has won on earth. The panel to His right shows the Virgin, gazing in devotion at an open book in her hands—a conception of such purity and innocence that it recalls the spirit of Fra Angelico. To his left is the equally nobly conceived figure of St. John, an open book in his lap, with his right hand raised, as it were, in exhortation. The monumental style of these figures, and their deep significance, leave no doubt that these panels are from the brush of the elder brother Hubert.

These panels are flanked by two shutters on each side—a choir of angels and St. Cecilia {52} with some angels within, and Adam and Eve at the extreme ends. The relentless realism of the latter, which borders close on ugliness, marks them as the work of Jan. The figures are undoubtedly painted from life, and were held to be so wonderful that for some time the whole altar-piece was known as the "Adam and Eve painting." Jan may also be held responsible for the angels and St. Cecilia, both of which have many characteristics that tally with well-authenticated works by the master. The predella which originally adorned the altar-piece has unfortunately been destroyed. The reverse of the lower shutters shows the figures of St. John the Evangelist, St. John the Baptist, and portraits of the donor, Jodoc Vydt, and his wife; and of the upper shutters, the Annunciation and figures of prophets and sibyls. Only the Adoration and the three important panels above (God the Father, the Virgin, and St. John) remain at the Cathedral of St. Bavo at Ghent; the Adam and Eve are now at the Brussels Museum, and the other shutters at the Berlin Museum.

There are still extant portions of a copy of this great work which was painted at the command of Philip II. of Spain by Michael {53} Cocxie. The wings of this copy are now added to the original centre portion at Ghent. There is a second copy of the Ghent altar-piece in the museum of Antwerp.

Upon the consecration of the great masterpiece at St. Bavo vast multitudes of people came into the city to see the work, the fame of which soon became known throughout the whole of Western Europe. And for more than four centuries it remained the wonder of Ghent.

Mr. R. Petrucci states that in 1904, during a demolition of a house in the Rue du Gouvernement at Ghent, the old walls were discovered of a Steen believed to have been the property of Jodoc Vydt, the patron of the van Eycks, who commissioned them to execute the Ghent polyptych. In a room upon the third floor, 40 feet up, a square window was discovered exactly answering in orientation and position to the town which appears in the Adoration of the Lamb, and which has been recognised as a view over the Rue Courte du Jour. In the foreground is seen the Steen, on the site of which was afterwards built the little butcher's shop near the present bird-market. Above it rises the tournelle of the weavers' chapel, which was used in turn as a butcher's shop, a pleasure {54} resort, and a place of auction, and is now a garage for motor-cars. Further away, in the background, is the old fortified gate which defended the passage of the bridge of the canal of the coppersmiths. On the left of the scene is a representation of another front of the Steen, which stood on that side at the corner of the Rue Courte du Jour and the Rue de Brabant. The window reveals this scene exactly. "It seems certain," says Mr. Petrucci, "that this was the room in which Hubert and Jan, or, at any rate, Jan, van Eyck painted the famous polyptych of the Mystic Lamb."

* * * * *

The portrait group by Jan van Eyck known as Jan Arnolfini and Jeanne dc Chenany, his Wife, must be counted among the greatest treasures of the London National Gallery, as it is, perhaps, the most perfect as well as the most characteristic example of the master's art. Arnolfini, who was Jan's brother-in-law, a man of solemn and depressing countenance, with heavy, drooping lids and long, wide-nostrilled nose, is seen standing in his bed-chamber. His right hand is raised as if enjoining silence, his left extended to his wife, whose open countenance denotes docility and calm. {55} Arnolfini wears a tunic of a dark green stuff, over which is a cloak of dark red, which reaches well below the knees, and is lined and edged with fur. It is divided at the sides from the bottom to the shoulder. He wears a large and curiously shaped hat, which in a manner resembles a "beefeater's" head-gear. His wife is habited in a long and ample robe of green, rather bright in colour, and lined and trimmed with white fur. She has raised the folds of the robe in front, thus revealing an undergarment of dark blue, trimmed also with fur. Round her strikingly high waist is a narrow belt of leather, decorated with gilding and polished. On her head is a large kerchief with a worked border, which is caught up at the sides in the prevailing fashion. Round her neck she wears a double row of pearls. The drawing of the drapery, which falls straight to the floor, is bold and severe, realistic, and devoid of any attempt at affectation.

In the foreground is a small dog, and to the left, on the floor, a pair of pattens. In the centre of the room, slightly behind and above the heads of the figures, hangs a brass chandelier of pierced work. Of its six arms only one holds a candle, and this is burning, the {56} single flame being probably a symbol of conjugal affection or unity, as there is no other reason for its presence in a chamber well lit by two large windows on the left—one behind the figures and one in advance, which is not shown, but the light from which falls straight upon the faces. On the wall behind the two figures a circular convex mirror reflects a portion of the room, with two additional figures. Beside it hangs an amber rosary. The flesh painting is admirably soft, delicate, and transparent; the light and shade powerful, yet so well arranged that only the closest examination will reveal what an important factor it is in the success of the picture. The whole thing is touching in the simple straightforwardness of statement, and all the details are wrought with inimitable but unobtrusive minute precision. In the management of tone-values and of indoors atmosphere Jan proves himself in this picture far ahead of his time.

The signature of this Arnolfini picture is written in ornamental Gothic characters immediately above the mirror, and takes the extraordinary form "Johannes de Eyck fuit hic" (Jan van Eyck was here), with the date 1434. Owing to this ambiguous wording, which may {57} be, and has been, interpreted as "this was Jan van Eyck," the picture was formerly held to represent the artist himself and his wife, a theory which still has its defenders. A full pedigree of the picture is given in the National Gallery catalogue. It belonged in 1516 to Margaret of Austria, to whom it was given by Don Diego de Guevara, whose arms were painted on the shutters which were originally attached to it. Afterwards it passed into the hands of a barber-surgeon at Bruges, who presented it to the then Regent of the Netherlands, Mary, the sister of Charles V., and Queen Dowager of Hungary. This Princess valued the picture so highly that she granted the barber-surgeon in return a pension, or office, worth 100 florins per annum. The picture is included in the list of valuables which she carried with her to Spain in 1556, from which date it disappeared until 1815, when it was discovered by Major-General Hay in the apartments to which he was taken, in Brussels, to recover from wounds received at Waterloo. He subsequently purchased the picture, and disposed of it to the British Government in 1842, since which date it has been at the National Gallery. Henri Bouchot was of opinion that the picture is not {58} the one of Arnolfini the traces of which are lost in 1556, but a portrait of van Eyck and his wife, painted as a pendant to the lost Arnolfini group. To support his view he pointed out the resemblance of the woman in this picture with the portrait of Jan's wife at the Bruges Museum.

* * * * *

PORTRAIT OF TIMOTHY.

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

The portrait at the National Gallery which, from the name inscribed in Greek characters on the stone parapet that extends across the bottom of the panel, is known as the bust of Timothy, bears the date October 10, 1432, and is therefore the earliest of Jan's signed and dated pictures—always excepting the much-overpainted Chatsworth panel of 1421. It is not in quite so good a state of preservation as the other portrait of a man by Jan, in the same Gallery, which is dated 1433, but the face itself is in fairly good condition. The features are broad and massive, and inclined to heaviness; the eyes are somewhat deep-set, while the cheek-bones are prominent. His right hand holds a small roll of parchment with some writing upon it. On the parapet, beneath the Greek word "Tymotheos," is the inscription LEAL SOVVENIR, and the signature {59} "Factū año. Dm̄. 1432. 10. die Octobris. a Joh. de Eyck."

* * * * *

The portrait known as The Man with the Pinks at the Berlin Museum, is one of the most characteristic of Jan's portraits. It shows an elderly man in a dark grey coat with fur cuffs and collar and a broad-brimmed beaver hat. At the neck the brocade collar of a tunic shows above the fur collar of the coat. The ornament of this brocade seems to consist of the alternating letters Y and C, which occur in one or two other portraits of the period, and may eventually afford some clue as to the identity of the sitter. Round the neck is a twisted wire chain, from which hangs a headless cross and the bell of St. Anthony. Both hands are raised as high as the breast, the fingers and thumb of the left holding three pinks. A handsome ring with two stones is on the third finger. The face, wrinkled and lined, is full of expression and life; the lips are parted, as though about to give utterance to speech. Though the drawing is almost hard in its exact delineation, it is far from rigid. It is altogether an admirable example of Jan's lifelike realism, that loves to dwell on every little ugly {60} detail—ill-shapen ears, puffy "tear-bags," warts and wrinkles—and yet infuses the whole thing with the beauty of life and character.

* * * * *

THE VAN DER PAELE ALTAR-PIECE.

BY JAN VAN EYCK.

The Virgin and Child, with St. Donatian, St. George, and the Donor, George van der Paele, Canon of the ancient Cathedral of St. Donatian at Bruges, bears the date 1436, and is the most important of Jan van Eyck's religious compositions. The scene is in the circular apse of a Romanesque church, lighted by the soft rays that filter through the leaded windows. The Virgin, draped in a red cloak, is seen in the centre under a green canopy, holding the Christ-Child in her lap. She has the same heavy, matronly features as the Virgin of The Annunciation in St. Petersburg and of the Chancellor Rolin picture in Paris, and is no more idealised than the by no means attractive infant Saviour, who is playing with a parrot. It is all very human and wonderfully true, and for that very reason lacking in spiritual significance. On the left stands St. Donatian in a gorgeous and marvellously painted brocade robe, whilst on the right St. George, in armour, presents the kneeling Canon van der Paele to the Virgin. The patron saint, again, {61} is obviously painted from a model of low rank in life—perhaps a peasant or a stableman; whilst the rugged irregular features of the donor are set down with an honest and painstaking straightforwardness that seems to delight in doing full justice to all the sitter's ugliness. As objective portraiture pure and simple, this head of van der Paele has probably never been surpassed in the whole history of art. The supreme mastery of Jan van Eyck manifests itself in the creation of a work of unforgettable beauty and sumptuous splendour from such unpromising material. The ugliness of the types chosen is forgotten when one's eyes revel in the rich scheme of colour, the extraordinary beauty of the painting of all the stuffs and accessories, the perfect modelling of the features, and, above all, the (for the time) amazing knowledge of the effect of light. With all the richness of pigment there is not a single note in this whole large panel that is not absolutely "in tone"; nothing is forced, nothing arbitrary, as though the fifteenth-century master had already adopted the principle of the nineteenth-century impressionists—"the first subject of a picture is light."

The van der Paele altar-piece was in the sacristy of the church of St. Donatian when {62} the old basilica was destroyed by the revolutionary troops. It was taken to Paris, together with much other artistic booty, but was returned to Bruges in 1814, and is now in the Museum of the Academy of that city. The drapery round the loins of the infant Saviour is a later addition which does not appear in the excellent early copy at the Antwerp Museum, from which our illustration is a reproduction. The original at Bruges bears the inscription in small Gothic letters: Hoc opus fecit fieri magister Georgius de Pala, huius ecclesie canonicus, per Johannem de Eyck pictorem. Et fundavit hic duas capellanias de gremio chori domini M. ccc°. xxxiiij°., completing anno 1436°.

* * * * *

At the Museum of Antwerp is the exquisite unfinished little painting of St. Barbara, signed and dated: JOHES DE EYCK ME FECIT 1437. The saint, with an open book on her lap and a palm-branch in her hand, is seated in front of an elaborately designed Gothic tower in course of construction. Around the tower are numerous figures of labourers, masons, horsemen, and others; and the background shows a landscape with mountains, castles, rivers, fields and trees, and a town on a hill. Technically, this picture {63} is supremely interesting, as it shows that at a comparatively late period of his life—a quarter of a century after the reputed discovery of oil-painting—Jan has not altogether discarded the practice of tempera-painting. For the whole composition, the pensive-looking saint and the widespread angular folds of her garment, the tower and the figures, are carefully drawn and shaded in brown tempera colour on a preparation of gum or white of egg. Only the part which required no special design, the sky, is painted in oil-colour. It may thus be assumed that it was the practice of the brothers van Eyck to work with oil-colours on a tempera foundation.

The St. Barbara also confirms Karel van Mander's statement that Jan's sketches were more complete and more carefully wrought than the finished paintings of other artists. M. Henri Hymaus suggests that this St. Barbara is the very painting which van Mander mentions as being in the possession of his master Lucas de Heere at Ghent, and "representing a woman behind whom was a landscape; it was but a preparation, and yet extraordinarily beautiful."

* * * * *

Our last illustration represents, or is supposed to represent, The Enthronement of Thomas à Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, and is in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire, at Chatsworth. In a late Norman church Thomas à Becket is seen in the foreground under a scarlet canopy, with the Holy Ghost hovering near, and above is a splendid crown in which the figure of the risen Christ is introduced; above the crown is a circle with a Virgin and Child. Three Bishops are engaged in placing the mitre upon the head of the saint, while a priest with an open book is kneeling before him. On the right are the clergy and on the left the laity, with King Henry II. at their head. On the border is the inscription: Johes de Eyck, fecit, ano, M°.CCCCZI, 30° Octobris. This inscription, if genuine, is the only evidence of Jan's authorship of the picture which has been entirely repainted, so that nothing of the original work is to be seen. The date, 1421, is eleven years earlier than any other dated picture by Jan van Eyck. It is scarcely necessary to point out the importance of this fact to the art historian in search of evidence of Jan's early activity; but whilst the picture remains in its present condition it cannot throw {65} any light upon the debated points. Only if the surface paint were removed would it be possible to judge whether below it is a real early work of Jan van Eyck, and what was the relative position of the two brothers before Hubert's death.

The Enthronement of Thomas à Becket has an interesting pedigree. It was given by John, Duke of Bedford, to King Henry V., and was afterwards in the collection of the second Earl of Arundel, who died at Padua in 1646, bequeathing it to Henry, the sixth Duke of Norfolk, by whose son, the seventh Duke, it was sold. It came through the Duke's steward, Mr. Fox, to a Mr. Sykes, who sold it to the Duke of Devonshire in 1722.

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY.

VIENNA MUSEUM.—Portrait of Jan de Leeuw (Jan), signed and dated 1436.

Portrait of Nicolas Albergati, Cardinal of the Church of the Holy Cross (Jan), painted, probably, in 1431, when the Cardinal passed through Flanders on a political mission. This picture is mentioned in the inventory of the Archduke Leopold William, Governor of the Netherlands, 1655. A silver-point sketch for the portrait is in the Dresden Print Cabinet.

BELGIUM.

GHENT, CATHEDRAL OF ST. BAVO.—The Adoration of the Lamb triptych (Hubert and Jan; see p. 46).

ANTWERP MUSEUM.—St. Barbara (Jan), 1437 (see p. 62).

The Virgin and Child by the Fountain (Jan), 1439.

BRUGES MUSEUM.—Virgin and Child, with St. Donatian, St. George, and the Donor, George van der Paele (Jan), 1436 (see p. 60).

Portrait of Jan Van Eyck's Wife (Jan), 1439.

BRUSSELS MUSEUM.—Adam and Eve: shutters from the Adoration triptych at St. Bavo, Ghent (Jan; see p. 52).

LOUVAIN, M. G. HELLEPUTTE.—Triptych of the Virgin and Child, with the Donor, Nicolas de Maelbeke, in Adoration, unfinished (Jan), 1340. The shutters contain representations of Gideon standing before an angel, the burning bush, Aaron with a blossoming rod, and other subjects from the Old Testament.

BRITISH ISLES.

CHATSWORTH, DUKE OF DEVONSHIRE.—The Enthronement of Thomas à Becket (Jan (?); see p. 64).

INCE HALL, MR. WELD BLUNDELL.—Virgin and Child (Jan): a panel of very small dimensions and miniature-like execution, painted in 1432, and inscribed Als ikh kan (As well as I can).

LONDON, NATIONAL GALLERY.—Jan Arnolfini and Jeanne de Chenany, his Wife (Jan), 1434 (see p. 54).

Portrait of Timothy, "Leal Souvenir" (Jan), 1432 (see p. 58).

Portrait of a Man with a Chaperon or Turban (Jan), 1433. Inscribed on the frame: Johes de Eyck me fecit anno MCCCC 33 21 Octobris, and Als ikh kan. Formerly in the Arundel Collection.

RICHMOND, SIR FREDERICK COOK.—The Three Marys at the Sepulchre (variously attributed to Hubert and Jan).

DENMARK.

COPENHAGEN, ROYAL GALLERY. Robert Poortier, protected by St. Antony (Hubert).

FRANCE.

PARIS, LOUVRE.—Chancellor Rolin kneeling before the Virgin and Child, with a river landscape seen through a loggia of three arches (generally ascribed to Hubert, but more probably by Jan).

BARON G. DE ROTHSCHILD.—Virgin and Child, with St. Anne, St. Barbara, and a Carthusian Monk, who has been identified as Herman Steenken, of Suutdorp, Vicar of a Carthusian Nunnery near Bruges (Hubert and Jan).

GERMANY.

BERLIN, NATIONAL GALLERY.—Six shutters from the Adoration altar-piece of St. Bavo, Ghent (Hubert and Jan; see p. 48).

A replica of the Virgin and Child, with a Carthusian Monk, in the collection of Baron G. de Rothschild, Paris.

Head of Christ (Jan), 1439.

Portrait of a Knight of the Golden Fleece, probably Baudouin de Lannoy (Jan).

The Man with the Pinks (Jan; see p. 59).

DRESDEN GALLERY.—Triptych, The Virgin and Child Enthroned. On the wings are the figures of St. Catherine and the donor, and on the back of the shutters the Annunciation (Jan).

FRANKFORT, STAEDEL INSTITUTE.—The Virgin and Child Enthroned (Jan).

LEIPZIG MUSEUM.—Portrait of a Man (Jan?).

ITALY.

TURIN GALLERY.—Copy of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata. The original is in the collection of Mr. J. G. Johnston, Philadelphia.

RUSSIA.

ST. PETERSBURG, HERMITAGE.—Calvary and the Last Judgment. Wings of a triptych, the centre portion of which is lost (Hubert?).

The Annunciation (Jan), formerly in the collection of King William II. of Holland. Bought for the Hermitage Collection for 13,000 francs.

SPAIN.

MADRID GALLERY.—Copy of a lost painting by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, representing The Triumph of the Church over the Synagogue, also known as The Fountain of Life.

UNITED STATES.

PHILADELPHIA, J. G. JOHNSTON.—St. Francis receiving the Stigmata (Hubert and Jan). A copy of this picture is at the Turin Gallery.

BILLING AND SONS, LTD., PRINTERS, GUILDFORD.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.