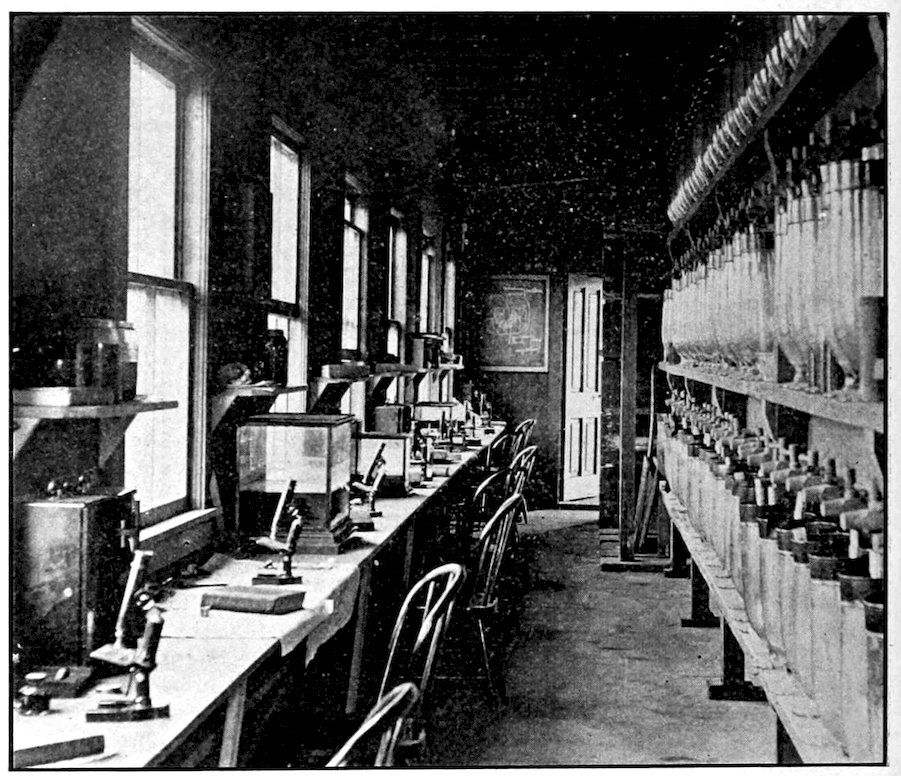

PART OF LABORATORY ROOM, LOWER FLOOR.

Title:The Ohio naturalist, Vol. I, No. 6, April, 1901

Author: Various

Release Date:August 26, 2023 [eBook #71494]

Language:English

Credits:Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

| Volume I. | April, 1901 | Number 6 |

A journal devoted more especially to the natural history of Ohio. The official organ of The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Published monthly during the academic year, from November to June (8 numbers). Price 50 cents per year, payable in advance. To foreign countries, 75 cents. Single copies 10 cents.

| The Lake Laboratory | 79 | |

| Herbert Osborn | ||

| Notes on the Flora of Sandusky | 82 | |

| W. A . Kellerman | ||

| Zoological Notes | 86 | |

| Herbert Osborn | ||

| Notes on the Bird Life of Cedar Point | 91 | |

| Robert F. Griggs | ||

| Plant Study at Sandusky Bay | 93 | |

| Harriet G. Burr | ||

| Dragonflies of Sandusky | 94 | |

| James S. Hine | ||

| Sponges and Bryozoans of Sandusky Bay | 96 | |

| F. L. Landacre | ||

| Additions to the Sandusky Flora | 97 | |

| Robert F. Griggs | ||

| Minor Plant Notes, No. 3 | 98 | |

| W. A. Kellerman | ||

| A List of Kansas Desmids | 100 | |

| John H. Schaffner | ||

| Mosses; Illustrative Samples | 102 | |

| W. A. Kellerman | ||

| Additional Note on the Syndesmon Involucre | 104 | |

| A. Wetzstein | ||

| Meetings of the Biological Club | 105 | |

| James S. Hine, Sec. | ||

| News and Notes | 106 | |

| Vol. I. | APRIL, 1901 | No. 6 |

Most readers of the Naturalist are probably aware that the University maintains at Sandusky a lake laboratory, devoted to the investigation and study of the life of the lake region. As this number of the Naturalist is devoted mostly to reports upon work which has been done there, it may be of interest to give some facts regarding opportunities offered and the character of the work provided for.

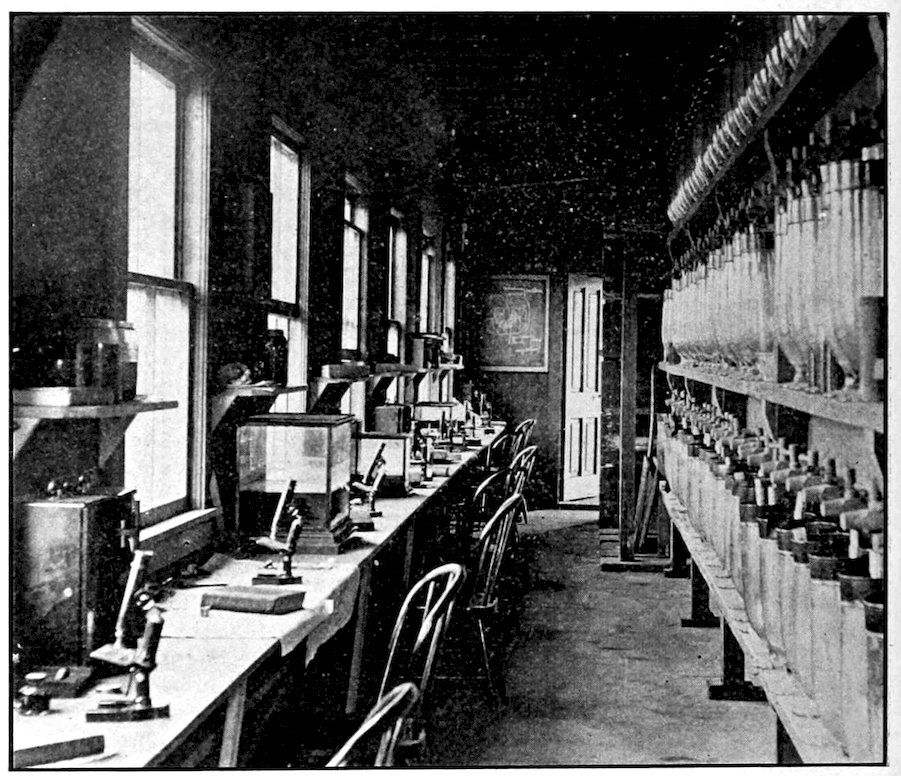

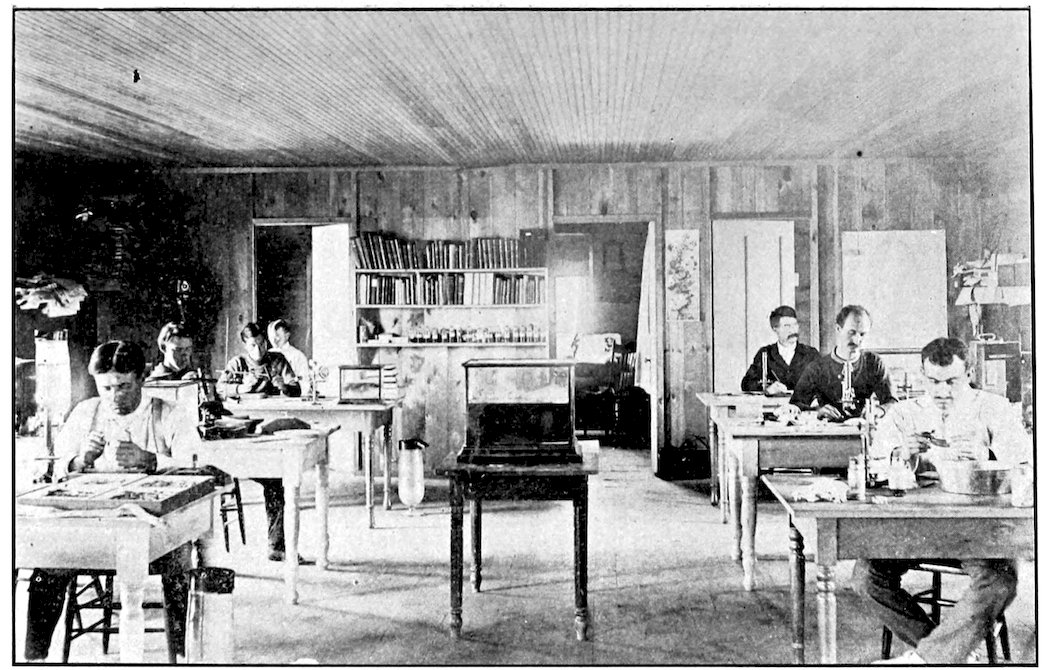

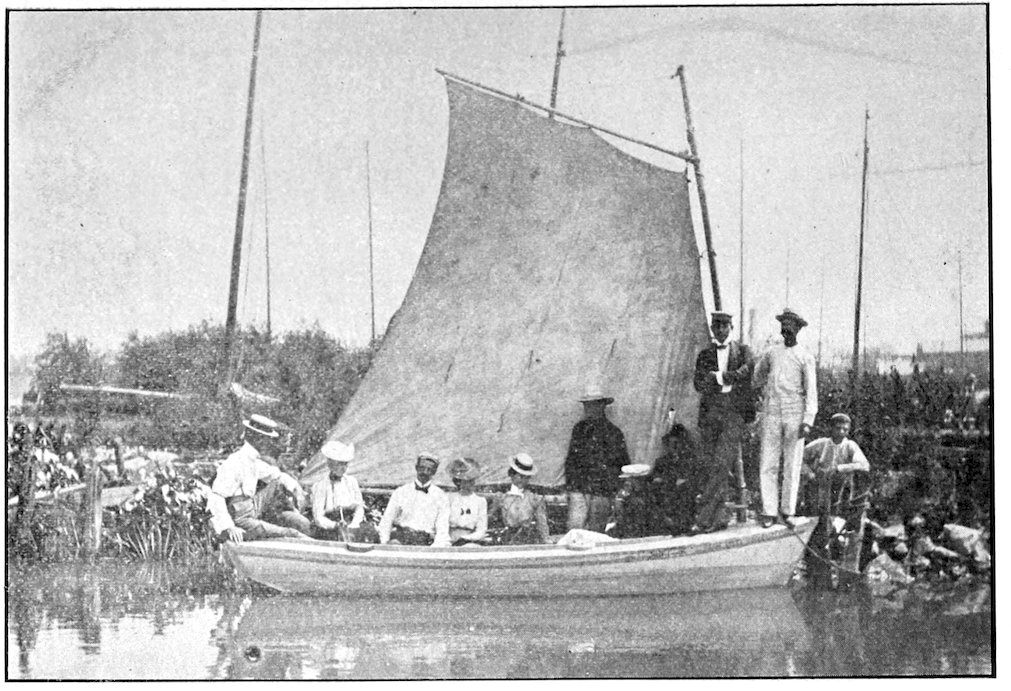

The laboratory was first opened by Professor Kellicott in 1895, with a view specially to give opportunity for investigation, and he and several of his students engaged in work there through the summers of ’95–6–7. Some of the results of these studies were published, especially Professor Kellicott’s report upon the Rotifers of Sandusky Bay and the list of Odonata for the State, which includes numerous records for that locality. During the summer of 1899 the writer and several associates occupied the laboratory, and studies upon the fishes of the locality, records of Hemiptera and some other groups have been incorporated in different papers. In 1900 the scope of the laboratory was enlarged so as to provide courses of instruction in Botany and Zoology, and a number of students and investigators improved the opportunity to work during the summer vacation. Reports on the Odonata, sponges, Bryozoa, and the notes on birds appearing in the present issue indicate the range of the studies engaged in that season. However, many lines of study which were begun by different students and which will require several seasons for observations, are not as yet ready for publication. It may be noted, however, that the flora of the locality has been very thoroughly collected by Professor Moseley, of the Sandusky High School, and his publication on the “Sandusky Flora” furnishes an admirable guide to the location of the various species of plants, and an excellent basis for additional investigation. The laboratory will at present accommodate twenty-five or thirty students, 80and its capacity will doubtless be increased as necessity requires. It is a two-story frame building 22 × 66 feet, the upper floor of which is used for investigation and the lower in part for students’ laboratory tables. It is supplied with city water, a number of aquaria, has a convenient dark room for photographic work, and answers admirably for the purpose for which it is used—that is, for a temporary summer laboratory. The laboratory is supplied with two boats equipped with sails, and designed especially for work in the bay and marshes. Dredges, seines, plankton net and other collecting apparatus are provided, while microscopes, microtomes, books, and other laboratory equipments are taken from the university.

PART OF LABORATORY ROOM, LOWER FLOOR.

Plate 6.

LABORATORY ROOMS OF UPPER FLOOR.

82While under the management of the Ohio State University, it is desired to make the laboratory as useful as possible to instructors and investigators in biology, wherever located. To this end table room is granted free of charge to qualified investigators, and any one wishing to undertake investigation of biological problems will be given all possible opportunity. Courses of study have been designed especially for high school teachers and for advanced university students, the former devoting themselves to methods of field work and preservation of material for laboratory use, and acquiring methods of laboratory work in connection with study of typical forms. For the latter, advanced courses in embryology, morphology, entomology, plant ecology, botany, etc., are offered. The students taking such courses can secure for them university credits covering equivalent courses in the university curriculum. It is needless to say that the opportunities for field observation, collecting, and the laboratory study of representative forms are most favorable. For special advanced courses in embryology, and particularly those pertaining to microscopical technique, the more elaborate equipment of the university is of course preferable.

The visitor or student at the Lake Laboratory will find in the neighborhood of Sandusky a flora in many respects peculiar and richer in species perhaps than in any other region of similar area in the state of Ohio. For our knowledge of the Sandusky plants we are indebted mainly to the continued and energetic explorations of E. L. Moseley, teacher of botany in the Sandusky High School. Our visits to the region have been numerous, and many weeks have been spent in herborizing during the last few seasons. Mr. Moseley’s Sandusky Flora (Ohio State Academy of Science, Special Papers No. 1) and additions by myself and Mr. Griggs reported before the Academy of Science, and published in The Ohio Naturalist, Vol. 1, fully represent our knowledge of this interesting flora to date.

In the “Sandusky Flora,” page 2, Mr. Moseley states that “the surpassing richness of the Sandusky flora is not due to the fact that it includes islands within its territory, for scarcely any of its species are confined to the islands; nor is it in a very large measure due to the fact that it includes species that are confined to the lake shore; but rather to peculiarities of climate and geological features, both of which depend to some extent on the proximity of the lake.”

Plate 7.

AT THE BOAT LANDING.

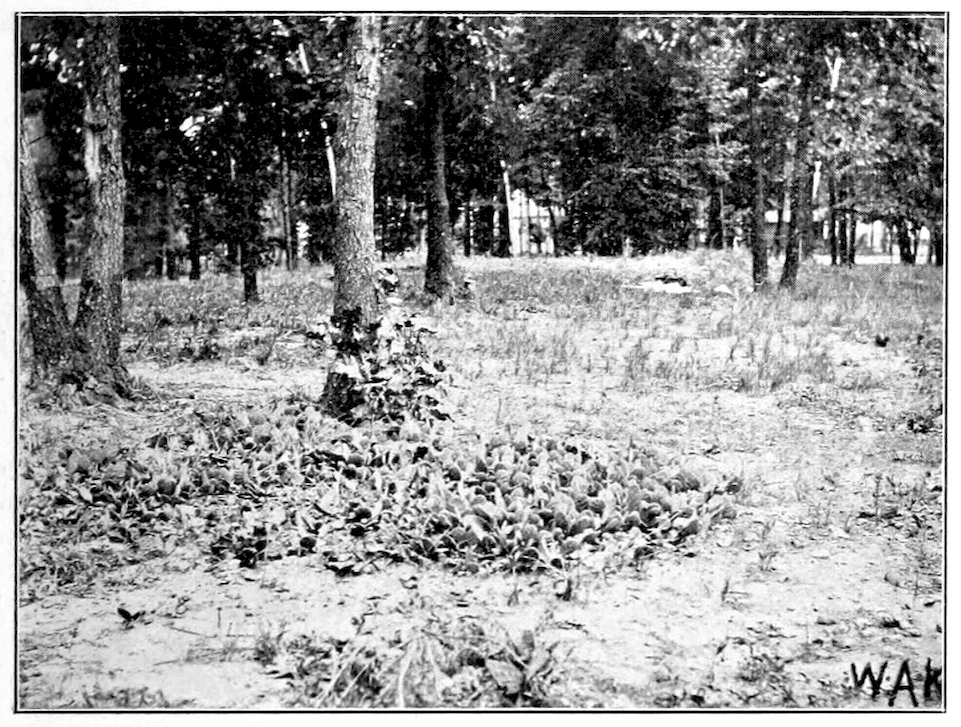

84Space will allow reference to but few of the interesting and rarer plants. On Cedar Point and a few other places the Prickly pear, Opuntia humifusa, appears in great abundance, but is reported for no other stations in Ohio. The illustration (Fig. 1) shows a patch of this plant, and also indicates the sparse vegetation in the open sandy Black Oak woods of Cedar Point. Here we found three specimens of the rare Lea’s Oak, one fine specimen of the common Juniper (Juniperus communis), two specimens of the Sand cherry (Prunus pumila), none of which are given in the “Sandusky Flora” for this place, and one only—the Juniper—for Catawba. Of other rare or specially interesting plants for this point the following may be mentioned: Ammophila arenaria, Panicum virgatum, Salix glaucophylla, Salix sericea, Euphorbia polygonifolia, Pinus strobus, Stipa spartea, Chenopodium leptophyllum, Lepargyraea canadensis, Œnothera rhombipetala, Artemisia caudata, Arctostaphylos uvaursi, Symphoricarpus pauciflorus, Utricularia gibba and Lacinaria scariosa.

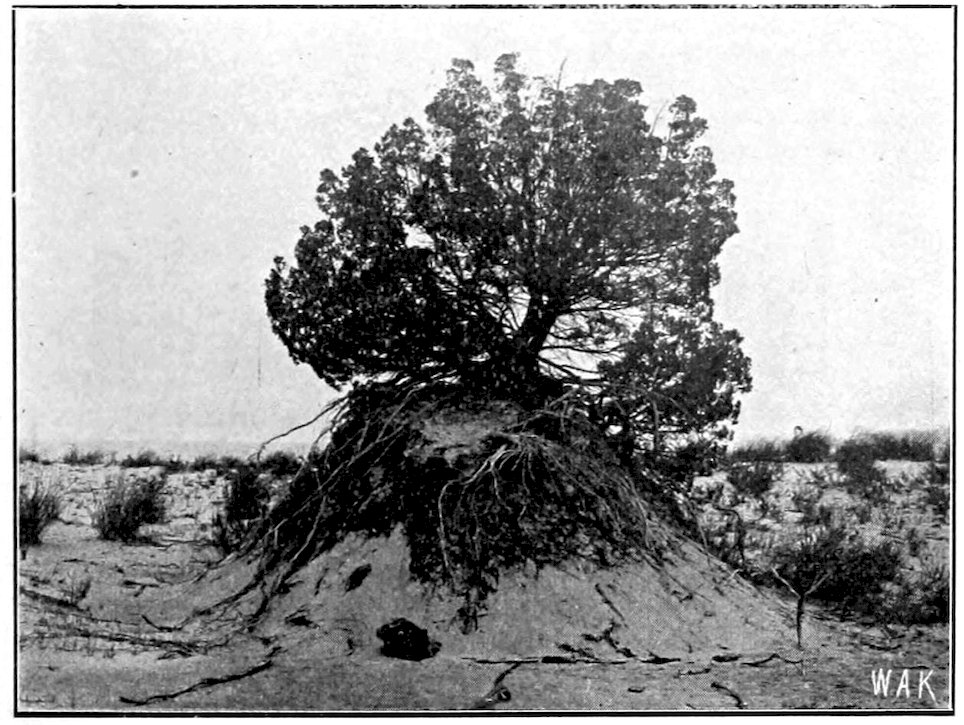

By no means the least interesting vegetation on Cedar Point are the dune plants, many species of arenophilous species, and efficient soil binders. Some idea of the appearance of a few of such plants may be gained from the cut (Fig. 2), which shows one of the sand hills held exclusively by the roots of the Red Cedar. Other similar hillocks are held by one of the wild grape vines, Vitis vulpina, and many other plants. The tufts of some of the grasses, especially Panicum virgatum, can be seen in the same illustration.

At Marblehead and Catawba the flora is equally rich in local and interesting plants. Huge Buckeyes occur, one of which measures nine feet and two inches in circumference. The Red Oaks are numerous and remarkably variable in their fruits. There occurs Zygadena elegans and Kœleria cristata, Meibomia illonoensis, Solanum rostratum, and Picradenia acaulis—all western species. The Lakeside Daisy, as the Picradenia has been locally named, is especially attractive. It occurs in one place in Illinois, but otherwise known only far west of the Mississippi river.

Elsewhere, and especially in the prairie region of Erie county, there occur such rare species as Aletris fainosa, Aristida gracilis and A. purpurascens, Salix candida, Prunus cuneata, Psoralea pedunculata, Rhexia virginica, Eryngium yuccifolium, Asclepias obtusifolia and A. sullivantii, and Helianthus mollis.

The bay is even richer, presenting acres and acres of Nelumbo, Sagittaria, Potamogetons, Rushes, Reeds, Duckweeds, Polygonum, Ceratophyllum, and others too numerous to mention. The innumerable and unenumerated Algae must not go unmentioned—here, as in many other lines, the enthusiastic students will reap a rich harvest.

Plate 8.

Fig. 1.—Prickly Pear in Woods of Black Oak, Cedar Point.

Fig. 2.—Sand Held by the Roots of Red Cedar.

KELLERMAN ON PLANTS OF CEDAR POINT.

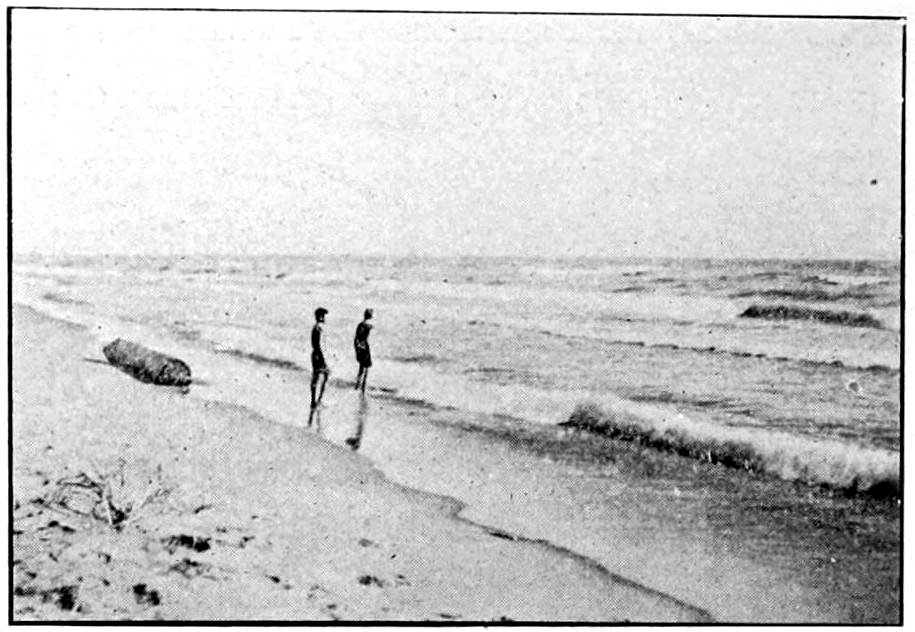

Cedar Point offers a number of rather peculiar features for study, and the fauna of the locality presents a very attractive field. On the one hand there is an extensive beach some six or seven miles in length, from which the sand dune formation extends backwards and merges into a swampy area bordering the waters of Sandusky Bay. On the beach after every storm will be found a large mass of drift material, including numerous fishes that have been thrown ashore. These furnish an attraction for a number of forms of animals, a complete census of which has as yet not been attempted. It may be mentioned, however, that numerous species of flies take to them to deposit their eggs, the larvae a few days after each storm being a conspicuous element to be followed a few days later by pupae or mature flies; these in turn attract various birds and large numbers of toads, which seem to secure a very constant source of food especially in this vicinity. Species of burrowing Hymenoptera are conspicuous and upon the sand dunes the grasshopper (Trimeroptropis maritima) is especially abundant. A millipede (Fontaria indianae) is also very abundant crawling over the sand, and turtles from the lake pass up the beach and over the dunes to deposit their eggs at favorable points.

Fig. 1.—A Bit of Cedar Point Beach.

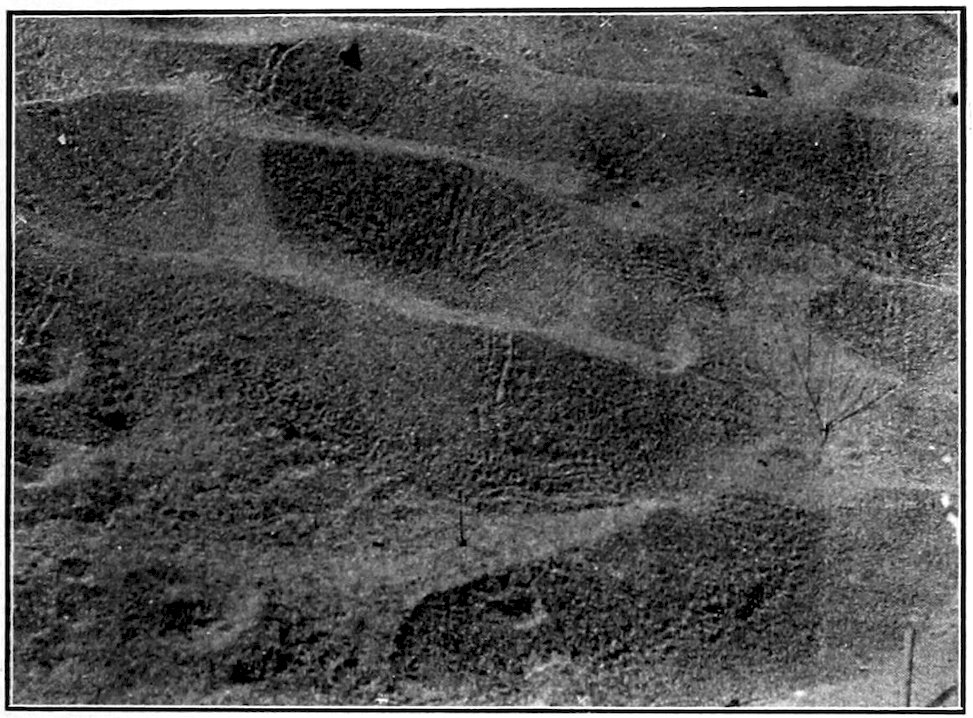

Foot Prints.—A study of the tracks and foot prints which are made in the sand is especially interesting, and the determination of 87species which are responsible for particular kinds of tracks is a fascinating though somewhat complicated study. Several of these have been identified with certainty, and a brief description of them in connection with a reproduction of some photographs may be of interest. Toad tracks are numerous and quite conspicuous and consist of four slight imprints in the sand, these occurring with regularity in length corresponding with the length of the leap and the tracks, with the distance between them, corresponding with the size of the individual. These are shown in Figure 2, between the points marked X. The abundant grasshopper, described more fully in another paragraph, produces when walking a continuous series of fine imprints in two or three more or less distinct lines on either side, midway between which is a narrow groove formed by the dragging of the abdomen. These tracks begin and end abruptly in case the insect is alarmed and leaps into the air. Several of these lines of imprint are shown in the figure—one distinct one above the point in Figure 2, marked +. Another very characteristic one that is easily referred to the millipede consists of parallel lines, in which the imprints of the individual feet are scarcely visible, and between which the sand is smoothed by the under surface of the body. In Fig. 2 under o.

Fig. 2.—Footprints of Toad, Grasshopper and Millipede.

Photo by H. Osborn.

Fig. 3.—Pitfalls and Tracks of Ant Lions.

Ant Lion.—Still another very characteristic member of the dune fauna is the ant lion, the larvae of which construct their characteristic pitfalls in slightly protected places near bushes or trees, sometimes in great numbers, indicating a very numerous colony of these curious creatures. Of these there are, judging by the larvae, two quite distinct species common to the Point, but these have not as yet been reared. Aside from the pitfalls these ant lions make a peculiar track in the sand when they are moving from one point to another. These movements apparently occur only during short periods, as is shown when an area which has been entirely free from such tracks will be noticed after an hour or two to be completely netted with their devious furrows, which could only be formed by a number of larvae. The larvae move backward, and from the character of the furrows produced in the sand, must remain just beneath the surface of the sand, as the sand is raised on either side. That the furrows are formed by these larvae is proven by the fact that if the pitfalls at their ends be dug into they will be found to contain larvae. The movements of the larvae, forcibly produced, 89make lines like those observed. Pitfalls and furrows are illustrated in the accompanying plates, the furrows being quite indistinct, as they are not deep enough to produce distinct shade, and consequently do not show conspicuously in the photograph. Furrows are to be noted, however, in the figure (No. 3) above the points marked X.

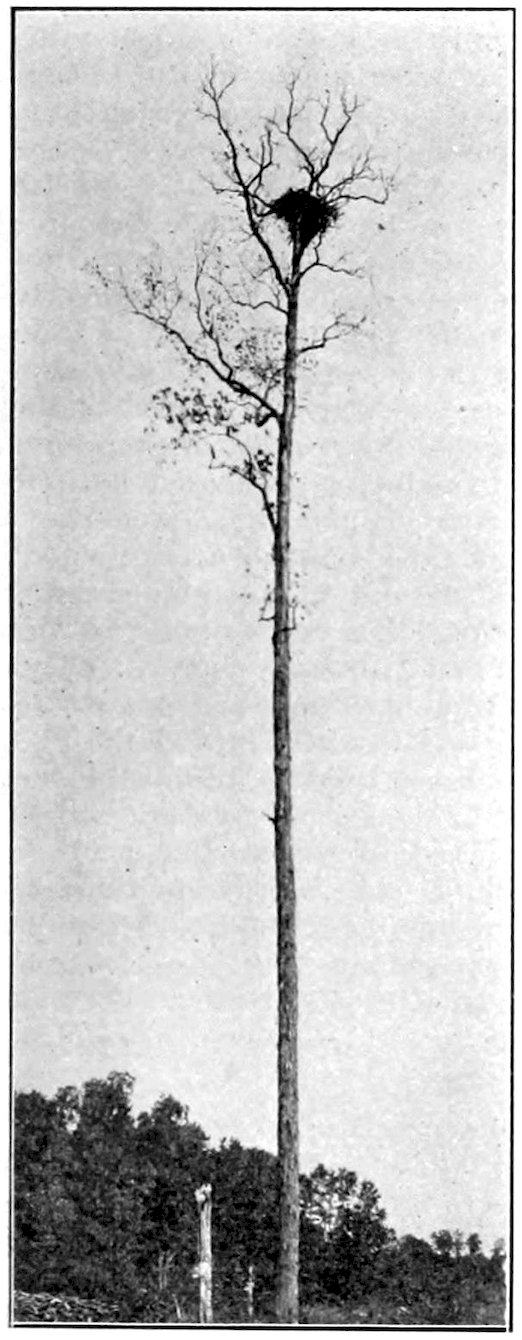

Fig. 4.—Eagle Nest.

Photo by R. F. Griggs.

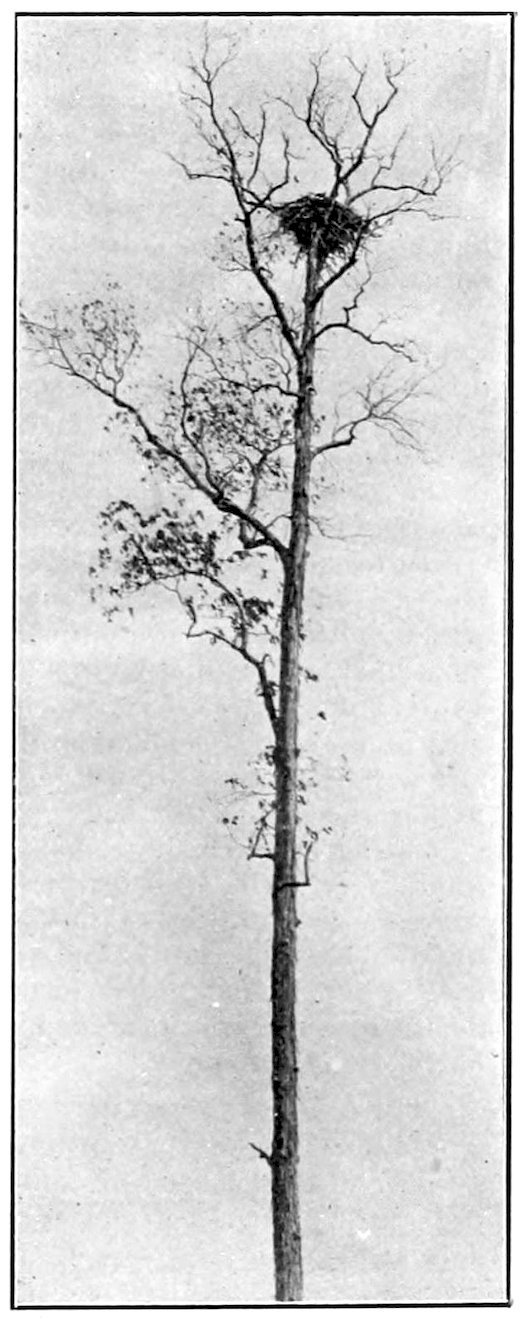

Fig. 5.—Eagle Nest.

Photo by H. Osborn.

Eagle Nests.—The bald eagle nests at various points along the lake shore, and some of these nests were observed, and photographs secured during the past summer. One of these is between Sandusky and Huron, about two miles from Huron, and a half mile from the Huron street railway, in a Shag bark hickory tree. It stands away from other timber, although it is said formerly to have been surrounded entirely by trees. It is probably one hundred and twenty-five feet in height, or more, and doubtless towered above surrounding trees, and at present constitutes the most conspicuous object to be seen for miles in any direction. The nest, as shown in the accompanying photographs, must be at least a hundred feet from the ground, but owing to the impossibility of climbing the tree, and from the fact that no exact means of measurement were at hand, the precise height is unknown. This nest, we were told, has been in this tree only a few years, but prior to its building one has existed in the immediate locality for at least thirty years past. The nest is evidently five or six feet in diameter, being somewhat more flattened than other nests observed, owing probably to the spreading character of the limbs upon which it rests. No eagles were to be seen at the time of our visit to the tree, but we were informed by the proprietor of the farm that they had reared a brood during the season, and one was seen later by Mr. Griggs, at the time his photograph was taken.

Other nests occur on Kelly’s Island, and we made a trip to that locality for the purpose of noting them and taking photographs, which, however, on account of the day being unfavorable, are not very clear, and cannot be reproduced to advantage. They are about a mile and a half eastward from the steamboat landing, one occurring in a Maple tree about seventy-five feet in height, and the nest at a height of about sixty-five feet, being at least six feet in height, fitting the somewhat acute crotch, and at least five or six feet across the top. The other is in a Burr Oak tree, some distance from other trees, in a vineyard, and plainly to be seen from the lake steamers when to the southeast of the landing. The tree is about a hundred feet high, and the nest is about eighty or eighty-five feet from the ground. It is similar in form to the one just mentioned. Portions can be seen to contain very large branches, which show out conspicuously from the ground.

Trimerotropis maritima.—This grasshopper which is very abundant on the dunes along Cedar Point Beach, is of special interest because of its protective resemblance to the sand on which it ordinarily rests. It is one of the best examples I have seen of adaptive coloration, but does not seem to have been mentioned in such connection, possibly because the colors change in preserved specimens so that the mimicry is totally lost. They reach maturity in latter part of June, and while only larvae are seen in middle of June, 91nearly all have matured by the latter part of July. They occur most abundantly on the sand adjacent to the clumps of grass upon which they doubtless feed, though so far no individuals have been observed actually feeding on grass leaves, but one was observed eating a fragment of apple cast up in drift materials on the beach. When disturbed they invariably alight on the sand, upon which they become at once invisible. About the only way to capture them is to throw a net down on a spot where one has been seen to alight, and then it not infrequently happens that two or even three will be caught though their presence has not been suspected.

The adult is whitish gray speckled with ferruginous fuscous and black, conspicuous ferruginous points occurring usually on the anterior margin of pronotum and on the lower borders of epimera of meso- and meta-thorax, humeri of elytra and discal carina of femur, these may be faint or obsolete, and on wings and legs may form slender lides; dark freckles occur on carinæ of vertex and face, forming a series back of collar on pronotum, on posterior border of pronotum and on sides of elytra and hind femora; on elytra they are thicker at three places, one-fourth, one-half and two-thirds from base, constituting fairly distinct patches, and on femur are two indistinct bands corresponding with well marked black bands on the inner side. Anterior and middle femora and tibiæ nearly white, milky, with gray annulations; hind tibiæ gray at base, distal two-thirds yellow, in one form orange or reddish, spines yellow, tipped with black, anterior and middle tarsi ferruginous or reddish, hind tarsi yellow. The sternum is finely pilose. A variety is quite uniformly yellowish gray.

The larvae are similarly speckled but differ in that the dorsum of abdomen is densely speckled, while in adults this part protected by the folded wings is not speckled. In all these points a perfect adaptation to the color and markings that blend with the sand grains is evident.

In the latter part of the summer of 1899, many of these grasshoppers died from an attack of parasitic fungus, and in such cases climbed up on stems of grass where their whitened bodies became very conspicuous. Eggs are doubtless laid in autumn probably in packed sand in grass clumps to hatch in following spring.

Ecologically Cedar Point is an exceedingly interesting region. It is a narrow peninsula on one side of which flourishes a xerophytic dune flora, and on the other a luxuriant hydrophytic marsh flora. The meeting of these two gives the flora a very peculiar aspect. 92Except at its tip Cedar Point has never been inhabited. It is still in very nearly its primitive condition. With a view to seeing how these and other factors peculiar to the region have influenced its bird life, these notes have been assembled. No pretentions to systematic completeness are made; the present purpose is more to determine the general character of the avifauna than to give a complete list including many accidental or occasional species which would overshadow the more characteristic residents. The observations upon which these notes are based were taken during the summer months (1900) when there were few species migrating, so that with the exceptions noted they include only the bulk of the summer residents at the Point. The birds of the marsh and bay are so inseparable from those of the point proper, that the commoner of them have been included, though no special study of them was made. The following birds were observed:

Sterna hirundo Linn. Common Tern, common.

Hydrochelidon nigra surinamensis (Gmel.). Black Tern, common, breeds.

Botaurus lentiginosus (Montag.). American Bittern, common.

Ardetta exilis (Gmel.). Least Bittern, common.

Ardea Herodias Linn. Great Blue Heron, common.

Gallinula galeata (Licht.). Florida Gallinule.

Fulica americana Gmel. Coot, common, breeds.

Ereunetes pusillus (Linn.). Semi-palmated Sandpiper. No specimens were taken to render identification sure-occurs in numbers on the beach.

Symphemia semipalmata (Gmel.). Willet, a few individuals.

Aegialitis vocifera (Linn.). Killdeer, common.

Zenaidura macroura (Linn.). Mourning Dove, not common, breeds.

Circus hudsonius (Linn.). Marsh Hawk.

Halæetus leucocephalus (Linn.). Bald Eagle, nests near the foot of the Point.

Coccyzus americanus (Linn.). Yellow-billed Cuckoo, scarce.

Coccyzus erythropthalmus (Wils.). Black-billed Cuckoo, quite common.

Colaptes auratus (Linn.). Flicker. I do not understand why the woodpeckers should not be well represented. There appears to be abundant feeding ground for them; yet I saw only one solitary flicker, the least specialised of all the woodpeckers.

Trochilus colubris (Linn.). Ruby-throated Hummingbird, congregates in small flocks about the frequent clumps of trumpet creeper.

Tyrannus tyrannus (Linn.). Kingbird, breeds. This and the other fly-catchers are very abundant on account of the great number of insects occurring.

93Myiarchus crinitus (Linn.). Crested Flycatcher, breeds.

Contopus virens (Linn.). Wood Pewee, very common.

Agelaius phœniceus (Linn.). Red-winged Blackbird, common.

Icterus galbula (Linn.). Baltimore Oriole, one small flock migrating.

Quiscalus quiscula æneus (Ridgw.). Crow Blackbird. This with the redwings and probably the other blackbirds congregates in very large flocks.

Melospiza fasciata (Gmel.). Song Sparrow, common.

Pipilo erythropthalmus (Linn.). Towhee.

Cardinalis cardinalis (Linn.). Cardinal, one pair.

Passerina cyanea (Linn.). Indigo Bunting, very common.

Petrochelidon lunifrons (Say.). Eave Swallow.

Chelidon erythrogaster (Bodd.). Barn Swallow.

Clivicola riparia (Linn.). Bank Swallow.

The Swallows flock to the beach by thousands after a storm, but are not abundant at other times.

Ampelis cedrorum (Vieill.). Cedar Waxwing.

Dendroica aestiva (Gmel.). Yellow Warbler, common, breeds.

Icteria virens (Linn.). Yellow-breasted Chat.

Galeoscoptes carolinensis (Linn.), Catbird, common, breeds.

Cistothorus palustris (Wils.). Long-billed Marsh Wren, very common, breeds.

Parus atricapillus (Linn.). Chickadee.

Merula migratoria (Linn.). American Robin, only one pair, seen only once.

Many birds common in most localities are conspicuous by their absence. The blue jay, crow, thrushes, most of the birds of prey, and the woodpeckers, and many of the sparrows, especially the ubiquitous English sparrow, were not observed at all. But the species occurring are present in great numbers, so that the region may be said to be monotonous in its bird life as well as in its other ecological relations.

To one whose work has not included collecting and study in such surroundings as Sandusky Bay affords, the revelation of even a few days here is worth a great deal. The marshes about Sandusky, the rocky islands, the sand dunes at Cedar Point, the “prairie” in the direction of Castalia, all offer valuable work to the student of ecology.

But during the week spent at the Lake Laboratory last August it was in study of the water plants of the Bay that I found the 94greatest interest. The collecting is after a manner novel to the “land lubber.” The collections, carried back to the Laboratory for study, have the fascination of the unusual, for represented among them are families more or less unfamiliar to general students.

A collecting trip for water-plants usually takes one across the Bay among the bulrushes and wild rice along Cedar Point. Here from the sides of the boat we look down into a wilderness of strange forms through the clear water. The curious eel-grass, with its perfect spirals, Myriophyllum and Chara, Philotria, Utricularia, and the Potamogetons spread out upon the surface among the lily-pads around us, are among the most conspicuous. A few minutes collecting here is productive of results quite out of proportion to the time spent. Many of these plants, at the time of my visit, had lifted themselves to the surface and bore their inflorescence above the water. Among these were some of the Potamogetons, Utricularia, Philotria, and others. A marigold looked strangely out of place on the surface of the water—it was the Bidens Beckii in bloom. The American Lotus lifted its head conspicuously above its lesser neighbors. Some minute, light-colored, fluffy masses, floating far out in the Bay, we decided to be the pollen of the Vallisneria.

I have said nothing of the Algae; the most of my work at the Laboratory, however, was with these forms. Many kinds are common and many more may be obtained by seeking for them. These types of plant life, in beauty of form and importance of study rivaled by none, repay much time spent upon them.

The collecting and study of only a week here—a week, too, of recreation rather than of work—was but a suggestion of what might be done, though one which proved quite powerful. From our landing at Cedar Point was visible, for a long distance out, the bright pink of a Swamp Rose Mallow. It typified the week’s work, it was a suggestion, too, of other strangers which might be lurking behind those trees and among those vines and undergrowth. We found that the suggestion was not a vain one, and in following it out we were never disappointed.

As the dragonflies of Sandusky have been quite carefully collected for a number of years, it may be worth while to give the result in the form of a list with notes on some of the species.

Calopteryx maculata and Hetaerina americana have not been taken as commonly as in some places, for the locality does not furnish their most desirable surroundings.

95The genus Lestes is represented by unguiculatus, uncatus, disjunctus, forcipatus, rectaugularis, vigilax, inequalis and eurinus. Nearly all of these species are abundant and are mostly found among the grass at the edge of the marsh.

The genus Argia is represented by four species, putrida, violacea, sedula and apicalis. The first two are very numerous in individuals.

Nehalennia posita and irene; Enallagma civile, ebrium, carunculatum, aspersum, exsulans, geminatum, antennatum, signatum pollutum; Amphiagrion saucium and Ischnura verticalis have all been taken, usually near the water’s edge.

The Gomphines are not represented by a great number of species. Gomphus vastus is exceedingly common, and fraternus, furcifer, exilis, spicatus and plagiatus have been taken. Dromogomphus spinosus is also common.

Epiaeschna heros and Æschna verticalis and constricta may occasionally be seen, especially about the time the sun sets, catching small insects for food. Anax junius is the most conspicuous species in the locality from May to September.

Macromia illinoiensis is a very common species. At certain times the males and females of this species may be found in numbers in quiet places among bushes, where they come to rest on the under side of branches, their bodies being at an angle of about thirty degrees with the branch. They are easily approached at such times, and two females and four males have been taken at a single sweep of the net.

Epicordulia princeps, Tetragoneuria cynosura, Tramea carolina and lacerata and Pantala flavescens are occasionally seen.

Neurocordulia yamaskanensis has only been taken once on Rattlesnake Island. It is a rare species, but one that is more common in the northern states.

The genus Libellula is represented by basalis, 4-maculata, semifasciata, pulchella and incesta; and Sympetrum by obtrusum, rubicundulum, vicinum, senicinctum and corruptum.

Pachydiplax longipennis, Plathemis lydia, mesothemis simplicicollis, Perithemis domitia, Leucorhinia intacta and Celethemis eponina and elisa are abundant, and with the members of the genus Libellula furnish a very large percentage of the dragonfly life of the Sandusky Marshes.

The two small groups of fresh water sponges and Bryozoa received some attention at the Lake laboratory during the summer of 1900.

All our fresh water sponges belong to one family, the Spongillidae, which has about seven genera. They differ from the marine sponges in two particulars. They form skeletons of silicon only, while marine sponges may form silicious or limy or spongin skeletons. The spongin skeleton is the one that gives the bath sponge its value.

They also form winter buds or statoblasts which carry the sponge over the winter and reproduce it again in the spring. This peculiar process was probably acquired on account of the changes in temperature and in amount of moisture to which animals living in fresh water streams are subjected. The sponge dies in the fall of the year and its skeleton of silicious spines or spicules can be found with no protoplasm. The character of the spines in the body of the sponge and those surrounding the statoblast differ greatly, and those around the statoblast are the main reliance in identifying sponges. So that if a statoblast is found the sponge from which it came can be determined, and on the other hand it is frequently very difficult to determine the species of a sponge if it has not yet formed its statoblast. The statoblast is a globular or disc-shaped, nitroginous cell with a chimney-like opening where the protoplasm escapes in the spring. The adult sponge is non-sexual but the statoblasts give rise to ova and spermatozoa which unite and produce a new sponge. The statoblast is considered as the sexual generation.

Three species belonging to one of the seven genera were positively identified.

Spongilla fragilis, Leidy, a very common form was found on submerged rocks on the south side of the bay near the city in great abundance. Its yellow statoblasts are numerous and placed in layers near the base of the sponge on the rock to which it is attached.

Another species Spongilla cinerea, Carter, was found on floating timber. It is ashen gray in color.

A third species Spongilla aspinosa, Potts, was found in Black Channel and near the city on submerged rocks. Its color is green. Other species were found but not definitely determined.

The fresh water Polyozoa comprise a small group of animals resembling the sponges in the process of statoblast formation, but otherwise totally different. Their real relationship is not definitely 97known. They are among the most beautiful of our lower fresh water forms. The body is nearly always protected by a cyst from which the anterior end of the animal projects when undisturbed and into which it can be retracted. There is a larval form resembling that of the worms and several other invertebrate groups, and a marked metamorphosis to the adult form. The statoblasts as in the sponges are of value in identification, and are formed on a strand of tissue connecting the base of the animal to its cyst. The individuals or Polyps increase in number by budding.

Two species are quite common at Sandusky. Plumatella polymorpha as its name indicates is quite variable in form. The variety repens was very common on the rocks on the south side of bay near the city. Its vine-like appearance renders it easy to identify. The Polyps are borne on the ends of the branches. The vine-like cyst clings closely to its support. The second species Pectinatella magnifica was found in Black Channel on submerged fish nets. It has a large spherical gelatinous base frequently eight or ten inches in diameter, over which the colonies of polyps are distributed. The individuals in each colony are arranged in the form of an aster. These large colonies are striking in appearance. The larvae are quite numerous and are globular in shape, and swim quite freely when liberated from the parent colony. The statoblasts are found in the fall as in the sponges. The process of statoblast formation and of larval development were studied, but the budding of individuals to enlarge the colony was not followed. The statoblasts of these animals seem to need to be both dried and frozen before development will go on in the spring.

The following plants not given in the “Sandusky Flora” have been collected in Erie county. They are here given in order that those possessing a copy of Professor Moseley’s excellent flora of the region may keep it up to date. The numbers refer to the pages of the Sandusky Flora, on which the additions should be made.

1. Previously reported as additions to State list. See Ohio Naturalist, 1: 15–16.

Sorghum Smut in Adams County.—A small field of Sorghum near Mineral Springs Station, Adams County, Ohio, was observed last November to be badly infected with the grain smut of Sorghum, known to botanists as ustilago sorghi, or perhaps more correctly designated (according to G. P. Clinton) as Cintractia sorghi-vulgaris. A careful inspection of the harvested stalks, still piled in the field, showed that fully twenty per cent. of the panicles or heads were infected. When there is infection by this smut, usually every grain in the panicle is smutted according to repeated observations in various localities. The field in question was very thickly planted to sorghum, the crop evidently being intended for stock feed. The only other locality reported in Ohio for this smut, so far as at present recalled, is Columbus, where however it has occurred only upon artificial infection. Broom corn also was here successfully infected. Sorghum is often cultivated, but not in large quantities in Ohio; a large acreage of broom corn is however annually planted. Request is hereby made for reports in case this smut is noticed in other localities in our State. The Head-smut of Sorghum, Ustilago reiliana, should also be reported if observed.

Notes on some Rusts.—M. A. Carleton, of the United States Department of Agriculture, has published some observations and experiments on a few rusts that are of special interest, and may well 99be noted here. He has shown that the common and abundant Spurge Rust, occurring on very many species of Euphorbia (twelve of which are listed in the Ohio Flora) is able to propagate itself constantly through the germinating seed of its host, and therefore becomes in that way practically a perennial species. He remarks that “It is the only demonstrated example of this manner of propagation in the whole order of Uredineae. Actual cluster-cups may be seen in the hulled seeds of Euphorbia dentata. Seedlings kept under bell jars become rusted three months from the date of planting, showing all stages of the rust, while seeds disinfected with mercuric chloride produce no rusted plants.”

Ohio Hybrid Oaks.—The Ohio Oaks have received as yet no critical study, though notes as to their variation have occasionally and indirectly got into print. It is often suggested that there may be numerous hybrid forms, though mere guesses are scarcely of any significance. Lea’s Oak, which is now known to occur in Ohio at four stations, namely, Cincinnati (the original locality reported), Brownsville in Licking County (tree since cut down), Columbus (one specimen), and Cedar Point in Erie County, has been known for years. It has been generally referred to Quercus imbricaria and Quercus velutina for its parentage, though Mr. Fischer was of opinion that the Columbus specimen was a cross between Quercus rubra and Quercus imbricarica. It was a matter of much interest when Mr. A. D. Selby reported, at the December Meeting of the Ohio Academy of Science, that he observed a hybrid Oak, a single tree, growing at Lakeville, Holmes County. The parentage he refers to Quercus alba and questionably Quercus inbricaria. He reports it with pronounced aspect of Q. alba “save in the elongated, short-lobed leaves which obviously approach those of Q. inbricaria.” While certain resemblances to Q. acuminata may suggest themselves (were his words) this species has not been observed in the immediate region. No mature fruit was seen. We may perhaps venture to suggest that the evidence for its hybridity between the two species named—one an annual-fruited and the other a biennial-fruited species—is suspiciously slender, and it is hoped that mature fruit and further inspection may put the case beyond doubt.

Asparagus Rust Abundant on Young Plants.—An inspection of the two patches of Asparagus on the University farm unexpectedly showed a more general infection of the plants which were but one year old. The older plants grow in the narrow flood plain of a little stream that flows through the farm to the Olentangy; throughout this patch which is perhaps a dozen years old, the infection is quite general, though very few of the plants show a large amount of the Rust, and no perceptible damage to the crop has hitherto been reported. A year ago seed was sown on higher ground 100about twenty rods from the old patch. The soil is mainly clay with some loam, and has been cultivated and fairly well manured for many years. The ground slopes to the west and is well drained, though the lower portion is perhaps somewhat inclined to be moist. The plants made an excellent growth. The infection throughout was general, quite a large percentage of the stalks at this season being very black from base to tip with the almost contiguous sori or blotches of Rust. Why these thrifty young plants should be so thoroughly infected, as compared with the older ones but a short distance away which have for several years harbored the Rust, though rather sparingly, is not clear to the observer.

A few years ago Prof. Lorenzo N. Johnson, of the University of Michigan, was at work on a monograph of the Desmids of North America, intending to make a comprehensive study of the American species; but his untimely death in the early part of the year 1897, prevented the fulfillment of this purpose. Some material which Prof. Johnson had received from Kansas proved very rich in species.

Thinking that a list of the determined Kansas species would make a valuable addition to the Kansas flora, I have obtained the following list of forty-seven species which was kindly furnished by Mrs. Johnson, of Evanston, Ill. I have verified the names, and arranged the genera in the order followed in Engler and Prantl. Very few localities were given in the card catalogue from which the list was taken, and only a few others could be added which were taken from Prof. Johnson’s published articles.

[This article was prepared as a suggestion for the Ohio Schools, and is issued simultaneously as No. 17 of the University Bulletin (Series 5.) A wide distribution is advisable and it seems desirable to issue it here also. Ohio teachers, pupils and amateurs will, it is hoped, become more interested in our bryological flora.]

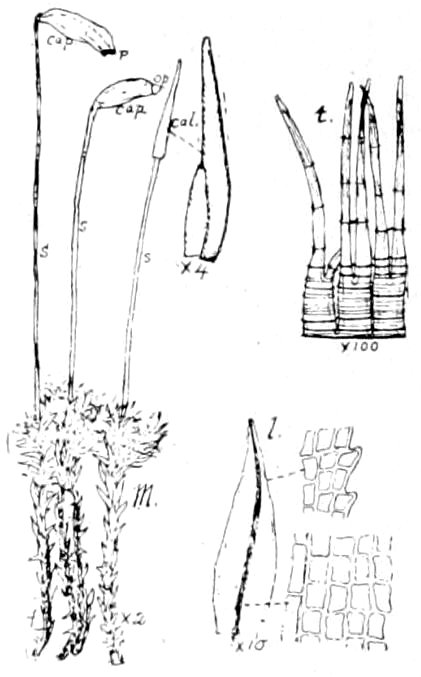

Fig. 1.[2]

2. Fig. 1.—A common Moss (M) bearing fruit (s and cap.); one capsule is old, one fresh, one immature and covered by the calyptra (cal.); the teeth (t) of the peristome (p), and a leaf (l) magnified, are also shown.

The samples on the accompanying attached sheet are intended to illustrate the kind of material to be collected, and the method of labelling and mounting the specimens, for the Herbarium. It will be noticed that most of the specimens are in “fruit,” which is the popular name for the “capsule” that terminates the “se-ta,” or slender stem. A delicate cap called the “ca-lyp-tra,” may usually be seen, completely or partially covering the capsule before it is fully mature. The terminal portion of the capsule, called lid or “o-per-cu-lum,” often drops off when maturity is reached; in this manner the “spores” or microscopical non-sexual reproductive bodies produced within, are allowed to escape. The mouth or opening of the spore case (capsule) is surrounded by a row of slender teeth, called collectively the “per-i-stome;” this may be clearly seen with the aid of a lens after the ripe operculum is removed. The accompanying diagrammatic figures illustrate the parts just mentioned.

The life history, or cycle of development, of our common Mosses may be briefly sketched as follows: When the spores germinate a slender branching tube, or alga-like filament, appears which has been designated the “pro-to-ne-ma.” This contains chlorophyll; it grows in moist protected places, and here and there develops root-like threads, called “rhi-zoids,” which anchor it to the soil. “Gem-mae” or buds also appear on the protonema and these develop into the upright clustered stems that bear the leaf-like structures. At the apex of the “ae-ro-car-pous” mosses, and from the sides in “pleu-ro-car-pous” species, there are formed the organs for sexual reproduction, namely, “an-ther-id-i-a” and “arch-e-go-ni-a;” these are surrounded by a cluster of leaf-like bracts, called 103the “per-i-che-ti-um” or perichetial scales. This structure, consisting of the delicate reproductive bodies and their conspicuous and surrounding protecting organs, has been called the “flower” of the mosses.

The microscopic bodies produced in the antheridia (and called “sper-mat-o-zoids”), and that produced in the archegonia (and called the “o-o-sphere”), are designated by the term “gam-etes;” it is their union that constitutes “fertilization.” It can now be understood why this stage of the development of the moss plant, as outlined in the preceding paragraph, is designated by the term “gam-e-to-phyte;” it is the plant (or generation) that produces the gametes. It is in popular language the “moss” plant.

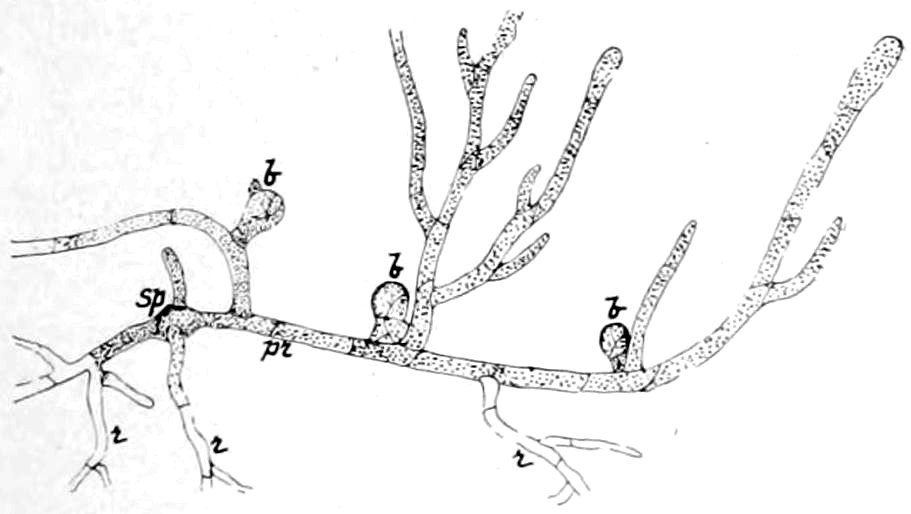

Fig. 2.[3]

3. Fig. 2.—The growth or protonema (pr.) from the spore (Sp.), having rhizoids (r), and buds (b), from which stems develop.

The fusion of the two gametes results in the production of the sexual spore, called the “o-o-spore;” it develops at once into the second generation, or second stage in the life-cycle of the moss plant, which is called the “spo-ro-phyte.” It consists of the seta and capsule; the lower end (“foot”) of the seta becomes early embedded and fixed in the tissue of the gametophyte, and from it is derived the nourishment necessary to complete the development of the sporophyte, or the plant that produces the numerous non-sexual spores. This “alternation of generations,”—that is, the alternation of gametophyte and sporophyte,—is not peculiar to Mosses, but occurs also in the Pter-id-o-phytes and Sper-mat-o-phytes.

I. Thal-lo-phytes; as the Slime-moulds, Bacteria, Common Algae (green Pond-scum, etc.), Marine Algae (“Sea-moss”), Moulds, Mildews, Smuts, Rusts, Mushrooms, Toadstools, Puffballs, etc.

II. Bry-o-phytes; The Mosses and Liverworts.

III. Pter-id-o-phytes; The Ferns, Club-mosses and Horsetails.

IV. Sper-mat-o-phytes; The Gymnosperms (Pines, etc.) and Angiosperms (Monocotyls and Dicotyls).

1. Sphag-na-les; the Bog-mosses or Sphagnum.

2. An-dre-æ-a-les; one genus of small Mosses in mountain regions.

3. Ar-chid-i-a-les; only one very short-stemmed species.

4. Bry-a-les; the common Mosses occurring in Ohio.

The only book that could be used by beginners in identifying Mosses, is Grout’s “Mosses with a Hand-lens,” price $1.10; procure if wanted from the author, or if placed in our hands the order will be attended to. The Manual by Lesquereux and James could be used by advanced students.

It is earnestly requested that contributions of Mosses for the State Herbarium from every County in Ohio be made. Please send an ample amount of each kind, enclosed in a temporary paper pocket or envelope; with each specimen lay a slip of paper or temporary label, giving locality, date and collector’s name, also any notes that are made with reference to habitat or habit of the plants. The donor’s name and other data will be placed on the permanent label accompanying the herbarium specimens.

In addition to the observations made by Mr. F. H. Burglehaus, Toledo, Ohio, concerning the involucral leaves of Syndesmon thalictroides Hoffmg., as stated in No. 5 of the Ohio Naturalist, I also confirm the contradiction in the habitus of plants growing in Auglaize County with the description in Britton & Brown’s Flora. All specimens I found here have no sessile involucral leaves, but petioles mostly about one-fourth of an inch in length. Especially the later flowering plants, that often grow over one foot high, show petioles of more than one-half inch in length, while even the earliest—collected about the middle of April, and no more than three inches high—exhibit distinctly petioled involucral leaves.

It might be very interesting to find out the range of plants with sessile involucres—for I do not at all think this description of Syndesmon to be an error in so carefully prepared a Flora as Britton & Brown’s is, the more as the given figure shows strictly sessile involucres too.

St. Marys, Ohio.

The meeting of the Biological Club, held in the Zoological lecture room on the evening of February 4th, 1901, was presided over by the president, Prof. Osborn, about thirty being present.

Prof. Lazenby presented “Remarks on Poisonous Plants.” He mentioned many of the poisons to which the poisonous properties of various plants are due. Many cases of poisoning are caused by poisonous fungi gathered with edible mushrooms, and greens gathered by persons unacquainted with poisonous herbs. Stramonium has been known to cause cases of poisoning by being gathered in greens. The distribution of poisonous plants through the various botanical orders was discussed, and the fact was revealed that a large percentage of the orders contain such species.

Prof. Ball spoke on “Collecting in Colorado.” His remarks on both faunal and floral conditions are valuable to all, and especially to those who collect in that western state. He emphasized the fact that in collecting Hemiptera, general sweeping is not productive of the best results. Many of the grasses which grow in that country are at least partially recumbent, and for that reason the sweeping net misses most of the desirable species. The species of insects which feed on these grasses are best taken by searching about the roots, or by lifting up the stems and scrutinizing them closely. Many new or rare species of Hemiptera have been procured in numbers in this way.

He exhibited many photographs and drawings which revealed the picturesqueness of the country, something of the flora, and the difficulties railroad companies experience in getting a track across the mountains, and left with many present a desire to see the remarkable scenery for themselves.

The Biological Club met in Townshend Hall on the evening of March 4, 1901, the lantern being kindly furnished and operated by Professor Hunt.

The board of editors through its secretary, Mr. Griggs, recommended that the offer of Professor Kellerman to take one-half the numbers of the first volume of the Ohio Naturalist for $125.00 be accepted; and that Professors Schaffner, Osborn and Kellerman be appointed a committee to consider the disposition of exchanges.

The report was unanimously accepted by the club.

106Mr. Griggs reported that he and Mr. Tyler had procured a set of two great horned owl’s eggs from an old hawk’s nest in a beech tree north of the city, on March 4th.

The paper of the evening was given by Professor Osborn on “The Naples Zoölogical Station.” The paper was illustrated by lantern and many views of historic places in Europe were given. Naples and the surrounding country with Vesuvius, Pompeii and other points of natural or historic interest were shown in a series of fine views from photographs. The station building with the beautiful grounds surrounding it appeared in several of the views. The speaker dwelt at some length on the opportunities given investigators, the methods of work, equipment in laboratories and library, and the cordiality of the staff in charge, and expressed the hope that many of the students in his hearing might at some future time enjoy the privileges of a sojourn at the station.

Mr. Modesta Quiroga was elected to membership.

In the present number of the Naturalist is published some of the work done last summer at the Lake Laboratory, located at Sandusky, O. For the announcement for the summer of 1901, or any other information, address Herbert Osborn, Director, Ohio State University, Columbus, O.

Special Papers No. 3, Ohio State Academy of Science, has been distributed. This paper deals with “The Preglacial Drainage of Ohio,” and the authors are W. G. Tight, Granville, J. A. Bownocker, Columbus, J. H. Todd, Wooster, and Gerard Fowke, Chillicothe. The paper is a neat pamphlet of seventy-five pages, with a number of maps and half-tones.

Referring to Burglehaus’ note on Syndesmon (Ohio Naturalist, 1:72), I may say that I have a number of specimens from Eastern Kansas, all of which have sessile involucral leaves. Some of the specimens in the Ohio State Herbarium have sessile leaves, while others have involucral leaves with petioles one inch or less in length. That there can be no mistake in the interpretation of what is supposed to constitute an involucral leaf is shown from the following statement in Britton and Brown’s Flora, 2:50:—“Involucre of three compound sessile leaves; leaflets stalked.” Mr. S. E. Horlacher, of Dayton, Ohio, writes that all the specimens in his herbarium agree with the Flora in having sessile involucral leaves. There may be several forms of Syndesmon distinct enough to designate as varieties; there is at least a large amount of variation.

Superior facilities for education in Applied Science. Short or special courses for mature students not candidates for degrees.

A neat pamphlet for every one who wishes to learn our native forest trees. Keys simple. Description plain. Can learn the names of the trees easily.

| Price reduced from 25 cents to | 10 cents. |

| Bound copies at cost of binding, namely | 20 cents. |

Teachers and others will also be interested in Prof. Kellerman’s Phyto-theca or Herbarium Portfolio, Practical Studies in Elementary Botany, Elementary Botany with Spring Flora, all published by Eldredge & Bro., Philadelphia, to whom apply.

For information or copies of Forest Trees and Catalogue or names of plant specimens of your region address

| PLANT RELATIONS, 12mo, cloth | $1.10 |

| PLANT STRUCTURES, 12mo, cloth | 1.20 |

| PLANT STUDIES, 12mo, cloth | 1.20 |

| PLANTS, 12mo, cloth | 1.80 |

| ANALYTICAL KEY TO PLANTS, 12mo, flexible cloth | .75 |

They are already the preferred texts, and the reasons will be apparent on examination.

By DAVID S. JORDAN, M. S., M. D, Ph. D., LL. D., President of the Leland Stanford Junior University, and VERNON L. KELLOGG, M. S., Professor in Leland Stanford Junior University. 12mo. Cloth, $1.20. Now ready.

Not a book for learning the classification, anatomy, and nomenclature of animals, but to show how animals reached their present development, the effects of environment, their place in Nature, their relations to one another and to the human race. Designed for one-half year’s work in high schools. Send for sample pages.

By DAVID S. JORDAN, M. S., M. D., Ph. D, LL. D., and HAROLD HEATH, Ph. D., Professor in Leland Stanford Junior University. Ready in February, 1901.

In Astronomy, Dr. Simon Newcomb’s new book, published October, 1900; in Physics, the Johns Hopkins text of Professors Rowland and Ames; also in Physics for second and third year high school work, the text of Dr. Hoadley, of Swarthmore; in Physiology, the text by Drs. Macy and Norris, based on the Nervous System; also the High School Physiology indorsed by the W. C. T. U., written by Drs. Hewes, of Harvard University; in Geology, the Revised “Compend” of Dr. Le Conte, and the two standard works of Dana,—The Manual for University Work, and the New Text Book, revision and rewriting of Dr. Rice, for fourth year high school work; in Chemistry, the approved Storer and Lindsay, recommended for secondary schools by the leading colleges; in Zoology, the Laboratory Manual of Dr. Needham, of Cornell; and the series “Scientific Memoirs” edited by Dr. Ames, of John Hopkins. Nine volumes ready.